Factors Affecting the Introduction of New Vaccines to

Poor Nations: A Comparative Study of the

Haemophilus

influenzae

Type B and Hepatitis B Vaccines

Aharona Glatman-Freedman

1,2,3

*, Mary-Louise Cohen

1

, Katherine A. Nichols

1

, Robert F. Porges

1,4

, Ivy

Rayos Saludes

1

, Kevin Steffens

1

, Victor G. Rodwin

5

, David W. Britt

6

1 Global Public Health Master’s Program, New York University, New York, New York, United States of America, 2 Department of Family and Community Medicine, New

York Medical College, Valhalla, New York, United States of America, 3 Department of Pediatrics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, United States of

America, 4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University, New York, New York, United States of America, 5 Robert F. Wagner School of Public Service,

New York University, New York, New York, United States of America, 6 Department of Health and Sports Sciences, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky, United

States of America

Abstract

Background:

A major effort to introduce new vaccines into poor nations of the world was initiated in recent years with the

help of the GAVI alliance. The first vaccines introduced have been the Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) and the hepatitis

B (Hep B) vaccines. The introduction of these vaccines during the first phase of GAVI’s operations demonstrated

considerable variability. We set out to study the factors affecting the introduction of these vaccines. The African Region

(AFRO), where new vaccines were introduced to a substantial number of countries during the first phase of GAVI’s funding,

was selected for this study.

Methodology/Principal Findings:

GAVI-eligible AFRO countries with a population of 0.5 million or more were included in

the study. Countries were analyzed and compared for new vaccine introduction, healthcare indicators, financial indicators

related to healthcare and country-level Governance Indicators, using One Way ANOVA, correlation analysis and Qualitative

Comparative Analysis (QCA). Introduction of new vaccines into AFRO nations was associated primarily with high country-

level Governance Indicator scores. The use of individual Governance Indicator scores, as well as a combined Governance

Indicator score we developed, demonstrated similar results.

Conclusions/Significance:

Our study results indicate that good country-level governance is an imperative pre-requisite for

the successful early introduction of new vaccines into poor African nations. Enhanced support measures may be required to

effectively introduce new vaccines to countries with low governance scores. The combined governance score we developed

may thus constitute a useful tool for helping philanthropic organizations make decisions regarding the type of support

needed by different countries to achieve success.

Citation: Glatman-Freedman A, Cohen M-L, Nichols KA, Porges RF, Saludes IR, et al. (2010) Factors Affecting the Introduction of New Vaccines to Poor Nations: A

Comparative Study of the Haemophilus influenzae Type B and Hepatitis B Vaccines. PLoS ONE 5(11): e13802. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013802

Editor: David Joseph Diemert, The George Washington University Medical Center, United States of America

Received March 23, 2010; Accepted September 24, 2010; Published November 2, 2010

Copyright: ß 2010 Glatman-Freedman et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors have no support or funding to report.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Childhood mortality continues to be a major global public

health problem. In 2005, approximately 9.7 million children

under the age of 5 died worldwide [1]. The United Nations

Millennium Developmental Goals (MDGs) delineated in 2002,

express a need for action through goal number 4, aiming for a

two-third reduction in childhood mortality from 1990 to 2015

(www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/mdg2007.pdf). Many child-

hood deaths occurring in poor nations result from diseases and

conditions which are easily preventable by vaccines that are

readily available in developed nations. Of the worldwide estimated

2.5 million deaths from vaccine preventable diseases among

children younger than 5 years of age, 87% occur in poor regions of

the world [2]. Furthermore, it is estimated that approximately 162

million Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) are lost worldwide

from vaccine-preventable diseases, more than 90% of them in low

income countries [3]. Until recently, funds for supply and

administration of vaccines in poor nations have been scarce and

inconsistent [4–6].

In 2000, a new global alliance for vaccine and immunization,

the GAVI Alliance (formerly known as the Global Alliance for

Vaccines and Immunizations), was established in an effort to end

vaccine inequity between rich and poor nations [5]. The GAVI

Alliance is a public-private partnership whose partners include UN

agencies, the World Health Organization (WHO), the World

Bank, public health institutions, donor and recipient countries, the

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, pharmaceutical manufactur-

ers, and other members of the philanthropic and financial

community (www.gavialliance.org/about/in_partnership/index.

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 1 November 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 11 | e13802

php). GAVI’s initial objectives were to provide the basic vaccines

(Polio, Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus, Measles and BCG) as well

as new and underused vaccines – particularly Haemophilus influenzae

type b (Hib), Hepatitis B (HepB) and Yellow Fever, to children

in developing nations (www.unicef.org/chinese/immunization/

files/immunize_every_child.pdf; http://www.gavialliance.org/

performance/global_results/index.php). GAVI’s funding has been

available to any nation with a Gross National Income (GNI) per

capita under $1,000 (www.gavialliance.org/support/who/index.

php) following an application review by independent experts

(www.gavialliance.org/support/how/index.php).

During its first phase of operation (2000–2005), GAVI provided

support for two new vaccines that have been readily available to

children in developing countries, the Hib and HepB vaccines (a

third vaccine against Yellow Fever is used only in Africa and South

America).

Hib is the most common cause of meningitis and a leading cause

of pneumonia in un-immunized infants and children under the age

of 5 years [reviewed in [7;8]. HepB virus can cause acute and

chronic Hepatitis, cirrhosis of the liver and hepatocellular

carcinoma; it can be transmitted at birth, through intimate or

sexual contacts and via needle sticks [9]. Vaccines are the most

effective preventive measure against both pathogens [9;10].

Despite the proven effectiveness of the Hib vaccine, its

introduction into immunization programs of developing nations

has been slow as compared with the HepB vaccine. By the end of

2005, fewer than 20 million children worldwide received a full 3

doses series of Hib vaccine as compared to more than 95 million

children that had received all 3 required doses of HepB (www.

gavialliance.org/performance/index.php). During the first phase

of GAVI’s operation, the number of GAVI-eligible countries using

Hib vaccine increased from 3 to 19, while HepB vaccine usage

increased from 17 to 57. (www.gavialliance.org/resources/15brd_

HepBHibYF_zuber_28Apr05.ppt); [11].

The purpose of this study was to investigate the conditions

which have been conducive to the successful introduction of the

Hib and HepB vaccines by GAVI into poor nations during its first

phase of operations. Recent experiences suggest that for healthcare

projects to succeed in poor countries, governments are central to

the delivery of services on a regional, national or global level, even

in the context of operations led by non-governmental organiza-

tions or the business sector [12]. Furthermore, governments in

poor countries were in some cases chief funders of public

healthcare efforts [12]. We thus examined systematically the

association of new vaccine introduction with different elements of

the healthcare, finance and governance context, characterizing the

nations in our sample of GAVI-eligible African Nations.

Methods

Countries

GAVI-eligible nations of the WHO African region (AFRO) with

a population size of 0.5 million or more were included in the study

(www.who.int/about/regions/afro/en/index.html). Only the is-

land of Sao Tome and Principe (population size 157,000) was

excluded (www.who.int/about/regions/afro/en/index.html). A

total of 35 countries were studied.

Data Collection

Vaccination data were obtained from WHO/UNICEF reports

(www.who.int/vaccines/globalsummary/immunization/country-

profileresult.cfm). Years of HepB and Hib vaccine initiation were

recorded for each country.

Country population sizes and Healthcare Indicators statistics

were obtained from the WHO database (www.who.int/whosis/

en/index.html). The healthcare indicators evaluated for each

country were: Life expectancy for males, life expectancy for

females, number of doctors per 1,000 people and number of

nurses per 1,000 people. The financial indicators related to

healthcare evaluated were: Total Healthcare Expenditure per

Capita (THECAP), Government Healthcare Expenditure per

Capita (GHECAP) and Total Healthcare Expenditure as percent

of the GDP (HEGDP).

Country-level Governance Indicators scores for each country

were obtained from the World Bank database (http://info.

worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.asp). These included: Po-

litical Stability (PS), Government Effectiveness (GE), Rule of Law

(Law), Regulatory Quality (Reg), Control of Corruption (Corr),

and Voice and Accountability (VA). The scores were provided as

percentile rank with higher values indicating higher performance.

The indicator values for 2005 were collected first, and if

statistically significant differences were found between the country

groups, indicator values were then collected and evaluated for the

years 1995 to 2005.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 15.0 for PC.

Mean, median and standard error were determined for each of the

continuous variables. Comparisons between different groups of

countries were done using One Way ANOVA. A p – value of

,0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the

relationship between variables using Pearson’s and Point Biserial

tests. Reliability was determined using Chronbach’s alpha.

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) was used to examine

the alternative combinations of factors that are conducive to the

success or failure of new vaccine introduction. QCA was

performed using fsQCA software.

Results

New vaccine programs in AFRO nations

New vaccine introduction data revealed that GAVI-eligible

African countries could be divided into 3 distinct groups based on

the status of new vaccine introduction or use during the first phase

of GAVI’s operation (2000–2005). The groups were defined as

follows (Table 1):

I. Countries in which both Hib and Hepatitis B vaccine were

introduced.

II. Countries in which Hepatitis B vaccine, but not Hib

vaccine, was introduced.

III. Countries in which neither Hib nor Hepatitis B vaccine

were introduced.

Country population size

The mean country population size was calculated for each

country group. No statistical differences were found between the

mean country sizes of the 3 groups.

Healthcare Indicators

The 3 country groups were compared for differences and

similarities in male and female life expectancy and number of

doctors and nurses per 1,000 people available by 2005, using One

Way ANOVA. No statistically significant differences were found

between the 3 vaccination country groups.

New Vaccines for Poor Nations

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 2 November 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 11 | e13802

Financial Indicators related to Healthcare

The 3 county groups were compared for differences and

similarities in Total Healthcare Expenditure per Capita (THE-

CAP), Government Healthcare Expenditure per Capita (GHE-

CAP) and Total Healthcare Expenditure as percent of the GDP

(HEGDP) using One Way ANOVA. Mean, standard deviation

and standard error of the mean of country group expenditure

values were first evaluated for 2005, and statistically significant

differences were found between the groups for Total Healthcare

Expenditure as percent of the GDP (HEGDP) and Government

Healthcare Expenditure per Capita (GHECAP) (Figures 1A, 1C).

Data were then collected for each country for the years 1995–

2005. Data for Total Healthcare Expenditure per Capita (THE-

CAP) were collected as well to evaluate pattern of expenditure.

The data summary is presented in Figure 1. For all 3 indicators the

means for group III were the lowest throughout the period studied.

The mean values for group II was higher and remained relatively

consistent throughout the period studied for all 3 indicators. The

mean values for group I of all indicators increased gradually with

the highest expenditure growth rate occurring after 2000 (the

beginning of GAVI’s funding period). For group I, GHECAP and

THECAP expenditure values were similar to those of group III in

the early pre-GAVI years, and by the end of the GAVI’s first

phase of funding, their values were the highest among the 3 groups

(Figures 1A, 1B).

For GHECAP, statistically significant differences were found

between group I and III for the years 2002, 2003 (p value,0.05),

2004 and 2005 (p value,0.01) (Figure 1A). For HEGDP, the

differences between groups I and III reached statistical significance

in the years 2004 and 2005 (p value,0.05) (Figure 1C). For

THECAP, the pattern of expenditure was similar to that of

GHECAP, but no statistically significant differences were

demonstrated between the groups (Figure 1B).

Country-level Governance Indicators

Political Stability, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Qual-

ity, Rule of Law, Control of Corruption and Voice and

Accountability scores (expressed as percentile rank) were collected

for each country. Country group means were then calculated for

each of the indicators. After determining that the country group

mean for 2005 for each indicator showed statistically significant

differences, scores were evaluated for the years 1996–2005 for

each country (with the exception of 1999 and 2001 for which

scores were not available).

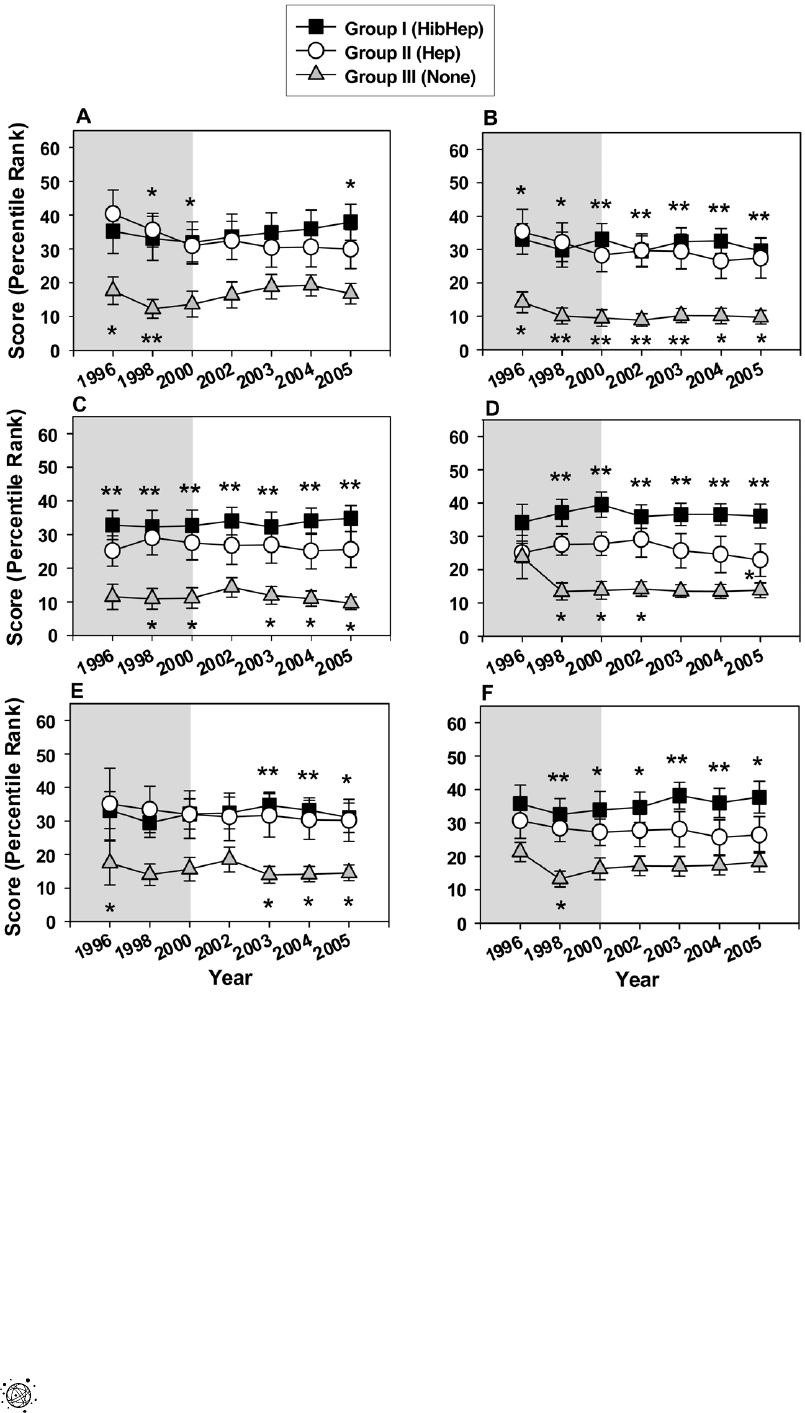

Overall, the mean scores were highest for group I and lowest for

group III (Figure 2). Multiple comparisons analysis demonstrated

that statistically significant differences were found between groups

I and III for all indicators (Figure 2A–F). Statistically significant

differences between groups II and III were also found for all

indicators, however, less frequently (Figure 2). Statistically

significant differences were found between group I and group II

only for Regulatory Control in 2005 (Figure 2D).

Correlation and reliability studies

Given the similar patterns of the various Governance Indicators

scores for the country groups (figure 2), we examined the

correlation between them for the years 1996 to 2005. A strong

positive correlation was found among all the Governance

Indicators (Table 2), with a statistically significant correlation

coefficient (p-value,0.01) for all of them. Analysis of correlation

between Governance Indicator means and country groups

(Table 2) demonstrated a statistically significant relationship (p

value#0.01). Reliability analysis performed using all the Gover-

nance Indicators for all the countries, demonstrated a Cronbach’s

Alpha score of 0.902.

Development of a combined governance scoring system

Given the high correlation and reliability scores for the

Governance Indicators, we set out to develop a single governance

score that will reflect the contribution of each indicator. A

Combined Governance Score, consisting of the average score for

all the Governance Indicators of each country for each year, was

calculated. Combined Governance Score means were then

calculated for each country group for each year in the period

studied. These scores, shown in Figure 3, demonstrated similar

pattern to that of the individual Governance Indicators, with the

highest scores for group I and the lowest for group III. Differences

between group I and III, were statistically significant with a p value

of ,0.01 for each year evaluated, except for 1996 when p value was

found to be ,0.05 (Figure 3). The differences between group II

and III were statistically significant with a p value of ,0.05 for all

the years studied. No statistically significant differences were found

between group I and II (Figure 3).

Prediction of success in the introduction of new vaccines

To complement the group comparisons across time, we used

QCA. Introduced by Ragin in 1987 [13], QCA is an analytic

technique which utilizes Boolean algebra for the purpose of making

multiple comparisons of various combinations of conditions, to

determine which combinations of conditions are most favorable to a

certain outcome. Thus, it is especially adept at examining the

alternative combinations of contextual elements that are conducive

Table 1. New vaccine introduction to GAVI-eligible AFRO

countries.*

Group I

Hib and

HepB

Group II

HepB

Group III

Neither

vaccine

Country Year Year Country Year Country

HepB Hib HepB

Benin 2002 2005 Cameroon 2005 Angola

Burkina

Faso

#

2006 2006 Comoros 2001 Chad

Burundi 2004 2004 Cote D’Ivoire 2001 CAR

Gambia

&

1990 1998 Eritrea 2002 Congo

Ghana 2002 2002 Lesotho 2001 Congo DR

Kenya 2002 2002 Madagascar 2003 Ethiopia

Malawi 2002 2002 Mauritania 2005 Guinea

Mali 2003 2005 Mozambique 2001 Guinea-Bissau

Rwanda 2002 2002 Nigeria 2005 Liberia

Senegal 2004 2005 Tanzania 2002 Niger

Uganda 2002 2002 Zimbabwe 1999 Sierra-Leone

Zambia 2005 2004 Togo

*Countries divided according to new vaccine (Hib and Hepatitis B) introduction

by 2005 and WHO/Unicef coverage reporting by 2006 (first vaccine coverage

reporting year is provided).

#

The application for HepB and Hib vaccines submitted by Burkina Faso was

approved in October 2004 (www.gavialliance.org/resources/

Info_Update_December2004.pdf).

&

Gambia started HepB and Hib vaccination program on its own. It was

approved for GAVI’s support for these vaccines in 2001 (www.gavialliance.org/

performance/country_results/index.php?countID = 23).

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013802.t001

New Vaccines for Poor Nations

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 3 November 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 11 | e13802

to programs’ success or failure. QCA is intended for use in studies

with small to intermediate N [13]. In the present study, QCA helps

draw attention to the alternative combinations of healthcare finance

and governance conditions that are associated with the successful

introductions of new vaccines.

The variables used for this analysis were the Combined

Governance Score, HEGDP and GHECAP, for the pre-GAVI

period, for each country (thus, the pre-GAVI means for the

Combined Governance Score were obtained by using the values

for 1996 and 1998 for each country, and the pre-GAVI mean for

HEGDP and GHECAP were obtained by using the values for

1995–1999 for each country). The median value of each mean

indicator score was then used to define high and low values. High

values were assigned the number 1, low values were assigned the

number 0, and these were then termed ‘conditions’ following

standard QCA practice. Table 3 demonstrates all the possible

combinations for the tested conditions. In addition, it demon-

strates the number of countries with each of the specific condition

combination, the number of countries in which a specific

combination of conditions was associated with the introduction

Figure 1. Financial healthcare indicators during the pre-GAVI and the first phase of GAVI’s funding. (A) GHECAP; (B) THECAP; (C)

HEGDP. Symbols represent means and error bars represent standard error of the mean. Grey plot background highlights the Pre-GAVI years, white

plot background highlights the GAVI funding years. * p value,0.05, ** p value,0.01. Placement of (*) above square symbols denotes a statistically

significant difference between country groups I and III.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013802.g001

New Vaccines for Poor Nations

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 4 November 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 11 | e13802

of at least one new vaccine, and the proportion of the countries

that the specific combination of conditions was associated with the

introduction of at least one new vaccine (defined as Consistency).

If a combination of conditions was associated with a

proportion of at least 0.75 of the countries being successful in

having at least one new vaccine introduced, that combination

was coded as a 1. If a proportion of less than 0.75 of the countries

was associated with that outcome, the combination was

considered as not successful in having at least one new vaccine

introduced and was code d as 0.

Of the 18 countries with condition combinations that included

high Combined Governance Score, 17 introduced at least one new

vaccine (Table 3). In comparison, of 18 countries with condition

combination that included either a high HEGDP or GHECAP

score, 13 and 14 countries respectively introduced at least one new

vaccine (Table 3). Thus, these results demonstrate that countries

Figure 2. Governance Indicators for the pre-GAVI and the first phase of GAVI’s funding. (A) Political stability; (B) Government

effectiveness; (C) Rule of Law; (D) Quality control; (E) Control of corruption; (F) Voice and accountability. Symbols represent means and error bars

represent standard error of the mean. Grey plot background highlights the Pre-GAVI years, white plot background highlights the GAVI funding years.

* p value,0.05, ** p value,0.01. Placement of (*) above square symbols denotes a statistically significant difference between country groups I and III.

Placement of (*) under triangle symbols denotes a statistically significant difference between country groups II and III. Placement of (*) under circle

symbols denotes a statistically significant difference between country groups I and II.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013802.g002

New Vaccines for Poor Nations

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 5 November 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 11 | e13802

with high Combined Governance Score (alone or in combination with high HEGDP or GHECAP) for the pre-GAVI years were

more likely to introduce at least one new vaccine than countries

with high HEGDP and/or GHECAP score (alone or in

combination with Combined Governance Score).

Overall, high Combined Governance Score of a country was

found to be the only condition associated with most cases of

success in terms of introducing at least one new vaccine.

Furthermore, this association with success occurred independently

of the presence of high HEGDP or GHECAP score in the

combination. As a result, the Combined Governance Score can be

declared both necessary and sufficient for predicting the

introduction of at least one new vaccine, with raw and unique

solution coverage of 0.74 and solution consistency of 0.94. Thus,

these results indicate that the Combined Governance Score by

itself correctly predicted 74% of the countries that were successful

in introducing at least one new vaccine (17 of the 23 countries

belonging to groups I and II). The results further indicate that the

Combined Governance Score demonstrated an average of 94%

consistency (17 of the 18 countries with high Combined

Governance Score). No good QCA solutions were found for

predicting the introduction of two new vaccines or distinguishing

between the introduction of one or two new vaccines.

Discussion

The GAVI Alliance’s initiative to introduce new vaccines into

developing countries is of utmost importance for the health of

children worldwide. The Alliance’s role in providing the financial

resources for this purpose is crucial, especially given the high costs

Table 2. Correlation between Governance indicator means for the years 1996–2005 and country groups.

CountryGroup PSmean GEmean LawMean RegMean CorrMean VAmean

Country Group Pearson Correlation 1 2.434(**) 2.570(**) 2.595(**) 2.651(**) 2.425(*) 2.517(**)

Sig. (2-tailed) .009 .000 .000 .000 .011 .001

N 35 353535 35 35 35

PSmean

#

Pearson Correlation 2 .434(**) 1 .662(**) .798(**) .608(**) .621(**) .783(**)

Sig. (2-tailed) .009 .000 .000 .000 .000 .000

N 35 353535 35 35 35

GEmean

#

Pearson Correlation 2 .570(**) .662(**) 1 .831(**) .823(**) .697(**) .720(**)

Sig. (2-tailed) .000 .000 .000 .000 .000 .000

N 35 353535 35 35 35

LawMean

#

Pearson Correlation 2 .595(**) .798(**) .831(**) 1 .742(**) .791(**) .704(**)

Sig. (2-tailed) .000 .000 .000 .000 .000 .000

N 35 353535 35 35 35

RegMean

#

Pearson Correlation 2 .651(**) .608(**) .823(**) .742(**) 1 .566(**) .699(**)

Sig. (2-tailed) .000 .000 .000 .000 .000 .000

N 35 353535 35 35 35

CorrMean

#

Pearson Correlation 2 .425(*) .621(**) .697(**) .791(**) .566(**) 1 .443(**)

Sig. (2-tailed) .011 .000 .000 .000 .000 .008

N 35 353535 35 35 35

VAmeanV Pearson Correlation 2 .517(**) .783(**) .720(**) .704(**) .699(**) .443(**) 1

Sig. (2-tailed) .001 .000 .000 .000 .000 .008

N 35 353535 35 35 35

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

#

PS – Political Stability, GE – Government Effectiveness, Law – Rule of LAW, Reg – Regulatory Quality, Corr – Control of Corruption, VA – Voice and accoun tability.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013802.t002

Figure 3. Combined Governance Indicator scores for the pre-

GAVI and the first phase of GAVI’s funding. Symbols represent

means and error bars represent standard error of the mean. Grey plot

background highlights the Pre-GAVI years, white plot background

highlights the GAVI funding years. * p value,0.05, ** p value,0.01.

Placement of (*) above square symbols denotes a statistically significant

difference between country groups I and III. Placement of (*) under

triangle symbols denotes a statistically significant difference between

country groups II and III.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013802.g003

New Vaccines for Poor Nations

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 6 November 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 11 | e13802

of such vaccines. The full Hib and HepB vaccine series, for

example, costs substantially more per child for a series of 3

vaccines, as compared to the battery of basic vaccines (Diphtheria,

Tetanus, Pertussis, Polio, Measles, Tetanus and BCG) [14]. While

the cost for the basic battery of vaccines has been US $1 per child,

the addition of Hib and HepB vaccines has raised the cost to US

$7–13 per child (www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs288/en/

index.html).

The GAVI alliance’s approach is unique in that it seeks to

provide financial support for vaccines while empowering nations

to become eventually self-sufficient in supporting their vaccination

programs (www.who.int/immunization_financing/analyses/fsp/

process/en/). To do so, GAVI initially required that countries

receiving GAVI’s support, outline in their applications their plans

to finance the vaccines costs in the future, and commit to prepare a

comprehensive Financial Sustainability Plan (www.who.int/im-

munization_financing/analyses/fsp/process/en/). However, to

achieve sustainable success, it is crucial to identify the factors that

contribute or hinder progress. Examining the first phase of GAVI’s

funding, we found that GAVI-eligible AFRO countries differed

with respect to the introduction of new vaccines into their

immunization programs. While some countries introduced both

the Hib and HepB vaccines (Group I), other countries introduced

only the Hep B vaccine (Group II). A third group of countries did

not introduce either vaccine (Table 1).

An initial analysis looking at the end of GAVI’s first phase of

operation (2005) suggested that higher financial indicator scores of

GHECAP and HEGDP and higher Governance Indicator scores

were associated with the introduction of both the Hib and Hep B

vaccines into countries’ immunization programs (Figure 1). A

more detailed analysis of the period from 1995 to 2005 (Figure 1)

demonstrated that while means of Governance Indicators scores

for group I (both Hib and Hep B vaccines introduced) remained

high and relatively stable throughout the pre-GAVI and the first

phase of GAVI’s funding periods (Figure 2), the mean GHECAP

and HEGDP values for country group I changed throughout these

years. Starting at low values in 1995, followed by a gradual

increase (Figure 1), they surpassed the values for both group II and

III by 2002. It is important to note that the largest increase in the

financial healthcare scores of group I occurred between the years

2000 and 2005 (Figure 1), coinciding with the first phase of

GAVI’s operations. This sharp increase in the financial healthcare

values of group I countries also coincided with the overall rapid

increase in developmental assistance for health (DAH) for low

income countries during these years [15]. Additional research is

required to understand the role and effect of GAVI’s funding in

these financial indicator increases of group I countries.

The stable pattern of governance scores for the 3 country

groups before and during GAVI’s first phase of funding, and the

association of higher governance scores with the introduction of

both HepB and Hib vaccines (country group I), solidly support the

strength of governance as an important factor in the ability of

countries to support healthcare initiatives, including the introduc-

tion of new vaccines. These patterns, coupled with the QCA

analysis results, strongly indicate that governance is a stronger

predictor for the introduction of new vaccines as compared to

healthcare financial expenditure.

It is interesting to note that overall, the countries that belong to

group II, which have similar governance scores to those of group I,

did not demonstrate increase in financial healthcare indicator

values during the first phase of GAVI’s funding. This observation

is particularly interesting given the fact that the differences in

governance scores between group I and II were not statistically

significant. Although it is possible that these small differences in

governance scores between groups I and II (with group II scores

being slightly lower than those of group I) were associated with the

inability of countries belonging to group II to increase the financial

healthcare expenditure and to introduce the Hib vaccine, our data

do not support such a conclusion. Furthermore, according to the

QCA analysis, no good solutions were found to distinguish

between countries that introduced one or two new vaccines. Thus,

these results suggest that the lack of introduction of a second new

vaccine (Hib) may be due to governmental decisions, lack of funds,

specific infrastructural issues or indefensible grant application for

GAVI’s Hib funds, rather than lack of governmental execution

abilities. It is also possible that these differences are due to lack of

sufficient country awareness for the role of Hib in causing

mortality and morbidity in countries belonging to group II.

However, recent global estimates demonstrating that most Hib-

related deaths have occurred in developing nations in Africa and

Asia [8], justify the need to introduce and expand the Hib vaccine

usage in these countries.

Overall, our results indicate that country-level governance is the

single most important factor in determining the ability of poor

African nations to introduce new vaccines. Good governance

offers an obvious advantage for a country’s ability to move forward

with new healthcare initiatives like the introduction of a new

vaccine. New efforts require the commitment and attention of

leadership at the top governmental levels who must obtain and

commit funds over multiple years. In nations that are struggling

Table 3. Prediction of introduction of at least one new vaccine based on indicator combination.

Indicator

Indicator

Combination

Combined

Governance

Score HEGDP GHECAP

Number of

countries with

condition

combination

No. of countries with the

condition combination

that introduced at least

one new vaccine

Condition

Combination

Consistency

Success in the

introduction of

at least one

new vaccine

1 1119 8 0.89 1

2 0 0 1 6 3 0.5 0

3 0106 2 0.33 0

4 0 0 0 5 1 0.2 0

5 1 0 0 3 3 1.0 1

6 1 0 1 3 3 1.0 1

7 1 1 0 3 3 1.0 1

8 0110 0 0 0

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013802.t003

New Vaccines for Poor Nations

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 7 November 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 11 | e13802

financially, political stability and good governance are often

important factors in attracting foreign aid [16]. In this regard,

good country-level governance was previously shown to have a

considerable impact on investments in developing countries made

by for-profit healthcare service providers and large multinational

pharmaceutical and biotechnology corporations [17].

In addition to funding, the introduction of new vaccines

requires adequate infrastructure elements such as sufficient cold

chain capacity, ability to reach remote locations, safe disposal of

needles and syringes, as well as sufficient numbers of adequately

trained personnel [18]. Lack or scarcity of these elements

constitute significant barriers to the adoption of new vaccines

[18]. Country-level governance may have a crucial effect on both

the initiation and mobilization of these important elements of

vaccine programs.

Combining Governance Indicators into a single index has the

advantage of providing one measure of governance that will take

into account all the indicators. Although overall, we found a

correlation between the various indicators of governance, some

countries received substantially different scores for different

Governance Indicators. Thus, a combined Governance score

which takes into account all the components of governance,

without the need to evaluate each one of them separately, provides

a user-friendly measure of governance.

Our results indicate that a scoring system that takes into account

all Governance Indicators (Figure 3) may constitute an effective

quantitative method to predict the ability of poor nations in Africa

to introduce new vaccines. There is a great need for quality

quantitative tools to support decision making in healthcare

philanthropy, and efforts to develop such tools are thus far at

their infancy (http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/09/philnpart/chapter5.

shtml). During its first phase of operations, GAVI strongly

encouraged nations to apply for new vaccines. GAVI has been

using a rigorous approach to evaluating, awarding and monitoring

its grants, while attempting to consider individual countries’

priorities, and promoting planning and country ownership.

However, an independent evaluation of the first phase of GAVI

found that it did not use a formal framework in directing its decision

making process regarding approval of funding (www.gavialliance.

org/resources/5._GAVI_Phase_1_Evaluation_Executive_Summary.

pdf). Thus, the association of new vaccines introduction with high

country-level governance scores reflects a phenomenon that is

independent of a specific framework. Our findings could provide a

basis for designing a framework and/or criteria that will guide the

evaluation process and the support required for introducing new

vaccines into nations with different levels of governance scores.

Overall, our findings suggest that for a new vaccine programs to

succeed, special considerations and criteria should be applied to

different countries. Countries with higher governance scores can

be expected to respond faster to GAVI and other international

vaccine initiatives. Although concerns regarding the financial

sustainability of these immunization programs are expected, it is

reasonable to assume that if financial resources are provided to

nations with higher governance scores, vaccination programs that

are in place will continue. However, in the absence of good

country-level governance, such as in the case of country group III,

the ability to respond to international vaccine initiatives will likely

be slower and the optimal use of financial assistance may be at risk.

Although the countries that pioneered the Hib program in sub-

Saharan Africa had overall good governance scores, a real

question remains whether, absent some significant price conces-

sion, even they can sustain this expensive vaccine once GAVI

funding ends. This question has become more relevant since

GAVI has continued to approve Hib vaccine funding to additional

African countries (www.gavialliance.org/media_centre/press_

releases/2007_11_29_en_pr_hib_boost.php). While some of these

newly approved countries had already introduced the HepB

vaccine beforehand, and they belong to an overall more

governmentally resourceful group of countries, most of them had

not used Hib or HepB vaccine before, and they belong to an

overall weaker group of countries with less effective governmental

systems.

GAVI has already begun modifying its criteria for financial

support for fragile countries. These include providing funds to

strengthen health systems (www.gavialliance.org/performance/

evaluation/index.php) and requiring lower co-pays for vaccines

(http://hibaction.org/resources/hibfocus/061117_alert/) [14]. The

need for additional support and different rules of engagement with

those nations (many of which are post-conflict) have been discussed

during GAVI’s meetings (www.gavialliance.org/resources/19brd_

FragileStates.pdf). Analysis of the second phase of GAVI’s funding

(from 2007 to 2010) will be required to evaluate the success of the

new changes in affecting new vaccine introduction. Ultimately,

established criteria, such as those used by the Center for Global

Development to assess the long-term success of global health

initiatives, namely: scale, importance, impact, duration and cost-

effectiveness [12], will probably be most suitable for this purpose.

The issues discussed in this paper are of paramount importance

for the continued introduction of new vaccines into developing

countries as well as maintaining and sustaining immunization

programs. In this regard, additional new licensed vaccines such as

Pneumococcal, Rotavirus, and Human papillomavirus vaccines are

planned to follow HepB and Hib vaccines (www.gavialliance.org/

vision/policies/new_vaccines/adips/index.php; www.gavialliance.

org/resources/FS_HPV_EN.pdf). If these vaccines are successfully

introduced into poor nations, they will likely facilitate the

introduction of novel vaccines to prevent tuberculosis, malaria

and HIV/AIDS when available.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. D. Modan-Moses for critical reading of the

manuscript and helpful suggestions.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: AGF VGR DWB. Performed

the experiments: AGF DWB. Analyzed the data: AGF DWB. Wrote the

paper: AGF MLC KAN RFP IRS KS. Data acquisition, data

interpretation: AGF. Data acquisition, drafting the article, final approval

of submitted version: MLC KAN RFP IRS KS. Critical revision of the

article for important intellectual content, final approval of the submitted

version: VGR DWB.

References

1. Murray CJ, Laakso T, Shibuya K, Hill K, Lopez AD (2007) Can we achieve

Millennium Development Goal 4? New analysis of country trends and forecasts

of under-5 mortality to 2015. Lancet 370: 1040–1054.

2. Anonymous (2006) Vaccine preventable deaths and the Global Immunization

Vision and Strategy, 2006–2015. MMWR 55: 511–515.

3. Mathers CD, Lopez AD, Murray CJL (2006) The burden of disease and

mortality by condition: Data, methods, and results by 2001. In: Lopez AD,

Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Mu rray CJL, eds. Glob al burden of

disease and risk factors. New York: Oxford University Press. pp 45–

240.

4. Aylward RB, Birmingham M, Lloyd J, Eggers R, Bilous J, et al. (2010) Reaching

every child: Achieving equity in global immunization. In: Levine MM, et al. (2010)

New Generation Vaccines, 4th edn. New York: Informa Healthcare. pp 91–

100.

New Vaccines for Poor Nations

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 8 November 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 11 | e13802

5. Jacobs L (2010) A paradigm for international cooperation: The GAVI Alliance.

In: Levine MM, et al. (2010) New Generation Vaccines, 4th edn. New York:

Informa Healthcare. pp 101–106.

6. Mahoney RT, Ramachandran S, Xu Z (2000) The introduction of new vaccines

into developing countries II. Vaccine financing. Vac cine 18: 2625–2635.

7. Watt JP, Levine OS, Santosham M (2003) Global reduction of Hib disease:

What are the next steps? Proceeding of the meeting Scottsadle, Arizona,

September 22–25, 2002. J Pediatr 143: S164–S187.

8. Watt JP, Wolfson LJ, Henkle E, O’Brien KL, Deloria-Knoll M, et al. (2009)

Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger

than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet 374: 903–911.

9. Zanetti AR, Van Damme P, Shouval D (2008) The global impact of vaccination

against hepatitis B: A historical overview. Vaccine 26: 6266–6273.

10. Roush SW, Murphy TV, Vaccine-Preventable Disease Table Working Group

(2007) Historical comparisons of morbidity and mortality for vaccine-

preventable disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2155–2163.

11. Rossi IA, Zuber PL, Dumolard L, Walker DG, Watt J (2007) Introduction of

Hib vaccine into national immunization programmes: a descriptive analysis of

global trends. Vaccine 25: 7075–7080.

12. Levine R, What works working group (2004) Millions saved: Proven success in

global health. Washington DC: Center for Global Development.

13. Ragin CC (1987) The comparative method: Moving beyond qualitative and

quantitative methods. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California

Press.

14. Akumu AO, English M, Scott JA, Griffiths UK (2007) Economic evaluation of

delivering Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine in routine immunization services

in Kenya. Bull WHO 85: 511–518.

15. Ravishankar N, Gubbins P, Cooley RJ, Leach-Kemon K, Michaud CM, et al.

(2009) Financing of global health: Tracking development assistance for global

health from 1990 to 2007. Lancet 373: 2113–2124.

16. Berthelemy JC (2006) Bilateral donors’ interest vs. recipients’ development

motives in aid allocation: Do all donors behave the same? Rev Develop Econ 10:

179–194.

17. Outerville JF (2007) Foreign direct investment in healthcare sector and most

favoured locations in developing countries. Eur J Health Econ 8: 305–312.

18. Duclos P, Okwo-Bel e JM, Gacic-Dobo M, Cheri an T (2009 ) Global

immunization: Status, progress, challenges and future. BMC Int.Health

Hum.Rights 9(Suppl 1): S2.

New Vaccines for Poor Nations

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 9 November 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 11 | e13802