The relationship between

immigration to Australia and

the labour market outcomes

of Australian workers

Migrant Intake into Australia

Technical Supplement A

January 2016

Robert Breunig

Nathan Deutscher

Hang Thi To

Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Except for the Commonwealth Coat of Arms and content supplied by third parties, this copyright work is

licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au

. In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt the

work, as long as you attribute the work to the Productivity Commission (but not in any way that suggests the

Commission endorses you or your use) and abide by the other licence terms.

Use of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms

For terms of use of the Coat of Arms visit the ‘It’s an Honour’ website: http://www.itsanhonour.gov.au

Third party copyright

Wherever a third party holds copyright in this material, the copyright remains with that party. Their

permission may be required to use the material, please contact them directly.

An appropriate reference for this publication is:

Breunig, R., Deutscher, N. and To, H.T. 2016, ‘The relationship between immigration to Australia and the

labour market outcomes of Australian workers’, Technical Supplement A to the Productivity Commission

Inquiry Report Migrant Intake into Australia, Canberra, April.

Publications enquiries

Media and Publications, phone: (03) 9653 2244 or email: maps@pc.gov.au

The Productivity Commission

The Productivity Commission is the Australian Government’s independent research and

advisory body on a range of economic, social and environmental issues affecting the welfare of

Australians. Its role, expressed most simply, is to help governments make better policies, in the

long term interest of the Australian community.

The Commission’s independence is underpinned by an Act of Parliament. Its processes and

outputs are open to public scrutiny and are driven by concern for the wellbeing of the

community as a whole.

Further information on the Productivity Commission can be obtained from the Commission’s

website (www.pc.gov.au).

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

1

The relationship between immigration to

Australia and the labour market outcomes

of Australian workers

Robert Breunig, Nathan Deutscher and Hang Thi To

*

Australian National University

15 January 2016

Abstract

We examine the relationship between immigration to Australia and labour market

outcomes of the Australian-born and previous immigrant cohorts. We use

immigrant supply changes in skill groups — defined by education and experience

— to identify the impact of immigration on the labour market. We find that

immigrants flow into those skill groups that have the highest earnings and lowest

unemployment. Once we control for the impact of experience and education on

labour market outcomes, we find almost no evidence that immigration has

harmed, over the decade since 2001, the aggregate labour market outcomes of

those born in Australia (natives) as well as incumbents (natives and previous

immigrants).

Keywords: immigration; Australia; native labour market outcomes; incumbent labour

market outcomes.

JEL Codes: J21,J31,J61,F22

A.1 Introduction

The impact of immigration on Australians, particularly on their wages and their

employment prospects, is a question that can provoke heated and emotional debate.

Anecdote and visceral impressions can easily dominate either side of the public

*

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Productivity Commission in preparing this

manuscript. This paper uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in

Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian

Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied

Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper,

however, are those of the author and should not be attributed to either DSS, the Melbourne Institute or the

Productivity Commission. All errors are those of the authors.

2

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

conversation. In this paper, we look carefully at the data to see if we can discern an effect

of immigration on the labour market outcomes of Australian workers. We look at outcomes

for two groups: those born in Australia (natives) as well as natives and previous

immigrants (incumbents).

A standard competitive labour market model suggests that immigration should have a

negative impact on wages. An influx of immigrants shifts the supply curve to the right,

depressing wages. This simple theoretical model, however, may fail to capture a variety of

other economic phenomena that may offset the negative wage effect.

One possibility is that the immigrant influx is part of a demand shift in the overall

economy. The demand shift would have the effect of raising wages and could dominate the

supply shift, resulting in higher wages for all. Another possibility is that immigrants may

fill roles that would otherwise be unfilled (e.g. mine workers, nurses or fruit pickers) and

the presence of these workers actually lifts the productivity (and wages) of incumbent

workers in related employment. The supply of capital, the characteristics of these new

workers and the structure of technology will all matter in determining the overall effect of

immigration on wages across the economy.

Congruent with this muddy theoretical picture, the literature paints a very mixed picture of

the effect of immigration on labour market outcomes of both natives and the broad group

of incumbent workers. Early literature in the United States pointed towards very small

effects of immigration on natives in that country (Friedberg and Hunt 1995 and Smith and

Edmonston 1997). Using a novel approach that moved away from geographical

identification and more towards skill-based identification, Borjas (2003) finds that the

employment opportunities of US natives have been harmed by immigration. More recently,

Ottaviano and Peri (2012) and Manacorda, Manning and Wadsworth (2012), extending and

refining Borjas’ work, find evidence for varying effects across population subgroups in the

US and UK respectively, with at times positive effects for native-born workers as a whole

sitting alongside negative effects for less educated natives and past migrants.

The above papers differ in their assumptions about the changing nature of capital, the

definition and size of skill groups and the substitutability of different types of labour.

Varying these assumptions appears to have a significant impact on the measured effects of

immigrants on labour market outcomes.

In this paper, we employ the approach of Borjas (2003). We divide the national labour

market into skill groups based upon education and experience. We examine whether

changes in the fraction of immigrants in skill groups are associated with labour market

outcomes for those working in Australia, after controlling for other factors. There are two

main advantages of our approach. First, it is data-driven and asks a simple correlation

question in a non-parametric way. Second, it allows for geographic mobility in labour

markets, which is ruled out in approaches that use the spatial distribution of immigrants for

identification.

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

3

We take two distinct approaches to defining the distinction between immigrants and

Australian workers, varying in their treatment of earlier migrants. This difference is

important, since around one-quarter of the Australian population is born overseas.

We first define immigrants as anyone born outside of Australia and focus on the labour

market outcomes of the Australian-born. We then consider the relationship between

outcomes for incumbents (those born in Australia plus those who migrated to Australia

five or more years previously) and recent (less than five years in Australia) migrants. We

examine a variety of outcomes: weekly earnings, annual earnings, hourly wage, weekly

hours worked, labour force participation and employment.

The analysis in this paper is restricted to considering effects of immigration on the labour

market outcomes of Australian workers, not their welfare more broadly considered. Such

an analysis is well beyond the scope of this paper.

We use three different data sets for our analysis. In one set of analysis we use the

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) series of Surveys of Income and Housing (SIH) to

estimate the number of migrants and non-migrants in each skill group. We use the same

data to measure the labour market outcomes of the Australian born. In a second set of

analysis, we match census data to the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in

Australia (HILDA) survey. In this case we use HILDA to estimate many of the labour

market outcomes of the Australian born but use complete census data to determine the

number of migrants and non-migrants in different skill groups. Results across both sets of

data are quite similar.

We find strong evidence of immigrant selection. That is, immigration flows into skill

groups where wages and employment are high. This is most likely a result of both

government policy and of the labour market decisions of immigrants. We find almost no

evidence that outcomes for those born in Australia have been harmed by immigration, with

the most statistically significant associations being with stronger labour market outcomes

for the Australian born. For incumbents, we find a negative relationship between

immigration and incumbent wages. However, this relationship is driven entirely by

highly-educated female workers with 10 years or less experience. This effect disappears

when we consider more precise skill groupings. Considered overall, the evidence suggests

that incumbent labour market outcomes have been neither helped nor harmed by

immigration.

In the next section, we discuss the definition of skill groups and the methodology that we

use. In section 3, we present the data. Empirical results are in section 4. As is the case with

all empirical work, the results are subject to certain caveats and these are discussed in

detail in section 5. We also provide some conclusions in this last section.

4

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

A.2 Methodology and related Australian literature

Our analysis examines the effect of immigration on labour market outcomes of Australian

workers using the national labour market approach (e.g. Borjas, 2003, 2006). In our

implementation of this approach, individuals are classified into five distinct educational

groups:

• high school dropouts (persons whose highest level of education was year 11 or below);

• high-school graduates (persons whose highest level of education was year 12);

• diploma graduates without year 12 education (persons who obtained a certificate or a

diploma but did not complete year 12);

• diploma graduates after completing year 12 (persons who obtained a certificate or a

diploma after having completed year 12); and

• university graduates (persons whose highest education was either a undergraduate or

post-graduate degree, or a graduate diploma certificate, after having completed

year 12).

Individuals are also classified into eight experience groups based on the number of years

that have elapsed since the person completed school.

1

We assume that the age of entry into

the labour market is:

• 17 for a typical high school dropout;

• 19 for a typical high-school graduate as well as for a typical diploma graduate without

year 12 education;

• 21 for a diploma graduate after completing year 12; and

• 23 for a typical university graduate after completing year 12.

The work experience is then given by the age of the individual minus the age at which the

individual entered the labour market. We restrict our analysis to people who have between

1 and 40 years of experience and aggregate the data into eight experience groups with

five-year experience intervals such as 1 to 5 years of experience, 6 to 10 years of

experience, and so on.

The individual data is aggregated into different education-experience cells. For each of

these cells, the share of immigrants in the population is given by:

=

+

where M

ijt

is the number of immigrants in cell (i, j, t), and N

ijt

is the number of

Australia- born individuals in cell (i, j, t).

1

In essence, we measure potential experience. This will be different for people of the same age depending

upon the age at which they finished their schooling/education. We refer to this as experience throughout.

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

5

We estimate the following specification:

=

+

+

+

+ (

×

) +

(

×

)

+

×

+

(1)

where:

• y

ijt

is the mean value of a particular labour market outcome for Australia-born workers

in cell (i, j, t);

• s

i

is a vector of dummy variables for education groups (i=1 to 5);

• x

j

is a vector of dummy variables for experience groups (j=1 to 8);

•

is vector of dummy variables for time (5 time periods for the SIH data and 3 time

periods for the matched HILDA / census data);

•

is a normally distributed random error.

The model includes time dummies to account for changes in the macroeconomic

environment that affect all groups. By including dummies for education and experience

and their interaction, we account for the supply and demand factors specific to each skill

group that determine the overall level of labour market outcomes for that skill group.

2

Interacting education and experience with time dummies allows the profile of skill groups

to evolve differently over time.

Identification in the model comes from changes within skill groups over time.

3

Differences

in the changes in the proportion of immigrants within cells are related to differential

changes in labour market outcomes. The approach is non-parametric in the sense that we

are allowing the data to relate changes in immigration to changes in labour market

outcomes without imposing any structural restrictions on this relationship. (We do not

estimate a wage equation, for example.) There is no need to control for other

characteristics such as average occupation or industry within a cell since these effects and

their evolution over time are perfectly captured by the fixed effects and the interactions.

One previous Australian paper used this approach. Bond and Gaston (2011) used only the

HILDA data to assess the effects of immigration on weekly earnings and weekly hours

worked of Australian-born workers. They found that immigrant share has a positive effects

on Australian-born workers’ earnings and weekly hours worked. Their approach is flawed

however because they used HILDA for both the outcome data and the immigrant share

data.

Since HILDA is a panel with an initial sample chosen in 2001, there is no inflow of

migrants into the sample.

4

The year-on-year change in the share of immigrants in the

2

These dummies allow the observed equilibrium outcomes to differ for each skill group. These observed

equilibrium outcomes could be driven by both demand and supply factors.

3

Using a model specified in first-differences gives similar results for the key coefficient,

.

4

Prior to the top up sample in 2011.

6

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

HILDA sample is driven by two factors: differential sample attrition of migrants and

non-migrants and a small number of migrants who join the sample because they partner

with a continuing sample member (or join the HILDA sample through one of the other

following rules of the data). Overall, population immigrant flows cannot be captured in any

meaningful sense through this panel data set.

Sinning and Vorell (2011) investigate attitudes towards, and the effects of, immigration on

the labour market and crime. They estimate the effect of immigration on SLA median

income and unemployment and LGA crime rates. They use data from 1996, 2001 and 2006

Censuses and crime statistics. To address selection issues, they instrument immigration

stock in a period with a counterfactual immigration stock created under the assumption that

new immigrants settle according to the last-period distribution of immigrants. The second

stage regressions include regional controls such as median age, population size,

educational and occupational distributions and region and time fixed-effects. In neither of

these preferred models is the immigration coefficient statistically significant. However,

their instrument is weak, with a first stage F-statistic below 10 when both period and time

fixed effects are included, clouding the interpretation of these results.

The geographic approach of Sinning and Vorell (2011) (and many others) has come under

increasing attack since Borjas (2003). The approach assumes that geographic labour

markets are fixed and distinct. Yet, we know that there are important movements of both

firms and workers that tend to equalize economic conditions across cities and regions. In

Australia, this trend is strongly seen in a shift of innovative activity and employment from

Victoria and New South Wales to Queensland and Western Australia during the time of

our data window.

Our approach allows for a national-level labour market but assumes no substitutability

across skill groups. Essentially, we assume fixed and distinct labour markets defined by

skill groups (rather than by sub-national geographic). Workers and firms are assumed to be

unable to change the skill group in which they supply or demand labour in response to

prices. Given that skill groups are defined broadly and in terms of experience and

education levels that are not able to be altered by workers, this assumption seems less

problematic than strict geographical segregation. Mobility across occupations, industries

and regions does not affect identification. The restriction that workers compete in skill

groups defined by education and experience is an important one and is discussed further in

sections 4.1 and 5.

A.3 Data

Our analysis is grouped into two parts. In the first part, we use data drawn from the SIH

conducted by the ABS. We use data from five biennial surveys from 2003 to 2012. The

survey collects information from usual residents of private dwellings in urban and rural

areas of Australia, covering about 98% of all people living in Australia. Private dwellings

are houses, flats, home units, caravans, garages, tents and other structures that were used as

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

7

places of residence at the time of interview. Long-stay caravan parks are also included.

These are distinct from non-private dwellings, such as hotels, boarding schools, boarding

houses and institutions, whose residents are excluded. The SIH contains a wide range of

information on demographic and economic characteristics of individuals and households.

In the second part of our analysis, we use data drawn from the Household, Income and

Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) combined with data from the Australian Census of

Population and Housing (Census).

The HILDA survey is a household-based panel study that collects information on

respondents’ economic and demographic characteristics. The wave 1 HILDA survey was

conducted in 2001 and has been conducted annually since. The vast majority of data was

collected through face-to-face interviews and a small fraction of the data was collected

through telephone interviews. 13 969 people were interviewed in wave one from

7682 households. The survey has grown slightly over time as all individual sample

members and their children are followed. The sample was replenished in wave 11 with a

top-up sample of 4009 people added in the survey.

The Australian Population and Housing Censuses provide information on the number of

people in each part of Australia, what they do and how they live. The data record the

details of all people (including visitors) who spend the night in each dwelling on Census

Night. Immigrants are included in the census provided that they intend to stay in Australia

for at least one year. The census data thus excludes those who intend to stay in Australia

for less than one year.

5

Census data contains information on topics such as age, gender,

education, birthplace and employment status of all people in Australia on Census Night.

6

In the first part of our analysis, we estimate the model of equation (1) using SIH data for

five financial years 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010, 2011–2012. We only

use data from 2003 onwards. Survey years prior to 2003-04 group education in broader

categories that are different than those used in 2003-04 and onwards. This makes it

impossible for us to extend our chosen skill group definitions further back in time than

2003.

We estimate the model for six different dependent variables relating to the labour market

outcomes of Australian-born workers: annual earnings from wage and salary, weekly

earnings from wage and salary, log hourly wage rate, weekly hours worked, the labour

force participation rate and the unemployment rate. The key explanatory variable of

interest, the share of immigrants in each education/experience cell, is also extracted from

5

We thank Jenny Dobak of the ABS for clarifying this.

6

We use the entire census data to construct the fraction of immigrants in each skill group. For 2006 and

2011, this data is available online through ABS table builder. For 2001, the data was constructed for us by

the ABS and provided through the Productivity Commission. We thank Meredith Baker and Troy

Podbury of the Productivity Commission and Steve Gelsi and Dominique O’Dea of the ABS for their

assistance in procuring the data. We also thank Sharron Turner at ANU for her assistance in helping us to

access ABS data.

8

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

the SIH as the survey samples, properly weighted, are representative cross-sections in each

year.

In the second part, we estimate the model of equation (1) using HILDA data combined

with complete Census data for 2001, 2006 and 2011. The explanatory variable of interest,

the share of immigrants in each skill group, is extracted from Census data. For the

dependent variables (labour market outcomes) we use the Census data for the

unemployment rate and the labour force participation rate of Australian-born workers. Data

for weekly hours worked, weekly and annual earnings (i.e. labour income) and hourly

wage rates are extracted from HILDA data as Census data do not provide individual

earnings in continuous values. We use cross-sectional weights from HILDA to make the

cell means representative. The weighted and unweighted means are almost identical. The

necessity of using immigrant share from Census data comes from the fact that the share of

immigrants in HILDA is not an appropriate indicator for the changing immigrant share in

Australia over time, as discussed above.

Descriptive statistics, from the SIH, of the main variables used in the analysis are provided

in figures A.1 to A.6. Figure A.1 presents the migrant share for each education-experience

cell, grouped by education category. For young people, migrant shares are relatively higher

in groups with university education compared to groups without university education. This

reflects the shift towards a higher skill requirement in Australian immigration policy in

recent years as well as strong labour market demand in Australia for highly educated

people.

Figure A.2 presents the mean values of annual earnings of Australian-born workers by

education and experience, grouped by education category. With the same experience,

annual earnings are higher for people with higher educational attainment. Annual earnings

increase faster for the young. The effect of experience is smaller after 20 years of

experience. For all groups we see the usual inverted U-shape earnings/experience profile.

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

9

Figure A.1 Migrant share by Education and Experience: SIH

Figure A.2 Annual earnings of Australian born workers by education

and experience: SIH

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

0.35

0.40

0.45

0.50

Year 11 Year 12 Diploma without

year 12

Diploma after

year 12

University

Proportion o migrants to total population

1-5 year experience 6-10 year experience 11-15 year experience 16-20 year experience

21-25 year experience 26-30 year experience 31-35 year experience 36-40 year experience

0

10000

20000

30000

40000

50000

60000

70000

80000

90000

Year 11 Year 12 Diploma without

year 12

Diploma after

year 12

University

1-5 year experience 6-10 year experience 11-15 year experience 16-20 year experience

21-25 year experience 26-30 year experience 31-35 year experience 36-40 year experience

$ per year

10

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

Figure A.3 shows the mean annual earnings of Australian born workers by education and

experience, respectively. We see very strong returns to university education and again an

inverted U-shape experience/earnings profile.

Figure A.3 Annual earnings of Australian born workers by education

and experience groups

Education

Experience

0

10000

20000

30000

40000

50000

60000

70000

80000

High school

dropout

High school

graduate

Diploma

graduates

without year

12

Diploma

graduates

after year 12

University

graduates

Total

$ per year

0

10000

20000

30000

40000

50000

60000

70000

1-5

years

6-10

years

11-15

years

16-20

years

21-25

years

26-30

years

31-35

years

36-40

years

Total

$ per year

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

11

Figure A.4 presents the unemployment rate of Australian born workers by education and

experience groups. The figures show that the unemployment rate decreases with the level

of education and with experience; the exception is slightly higher unemployment for those

in the highest experience group.

Figure A.4 Unemployment rate of Australian born workers by education

and experience groups

Education

Experience

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

High school

dropout

High school

graduate

Diploma

graduat es

without year

12

Diploma

graduat es

after year

12

University

graduat es

Total

Per cent

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1-5

years

6-10

years

11-15

years

16-20

years

21-25

years

26-30

years

31-35

years

36-40

years

Total

Per cent

12

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

Figure A.5 presents migrant share by education and experience from the Census data and

figure A.6 shows annual earnings by education and experience from HILDA. The overall

impression provided by the two data sets is quite similar.

Figure A.5 Migrant share by education and experience, Census

Figure A.6 Annual earnings by education and experience, HILDA

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

1-5 years 6-10 years 11-15

years

16-20

years

21-25

years

26-30

years

31-35

years

36-40

years

Share

Dropout Y12 Cert w/o Y12 Cert w Y12

Degree

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

80,000

1-5 years 6-10 years 11-15

years

16-20

years

21-25

years

26-30

years

31-35

years

36-40

years

Income ($)

Dropout Y12 Cert w/o Y12 Cert w Y12 Degree

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

13

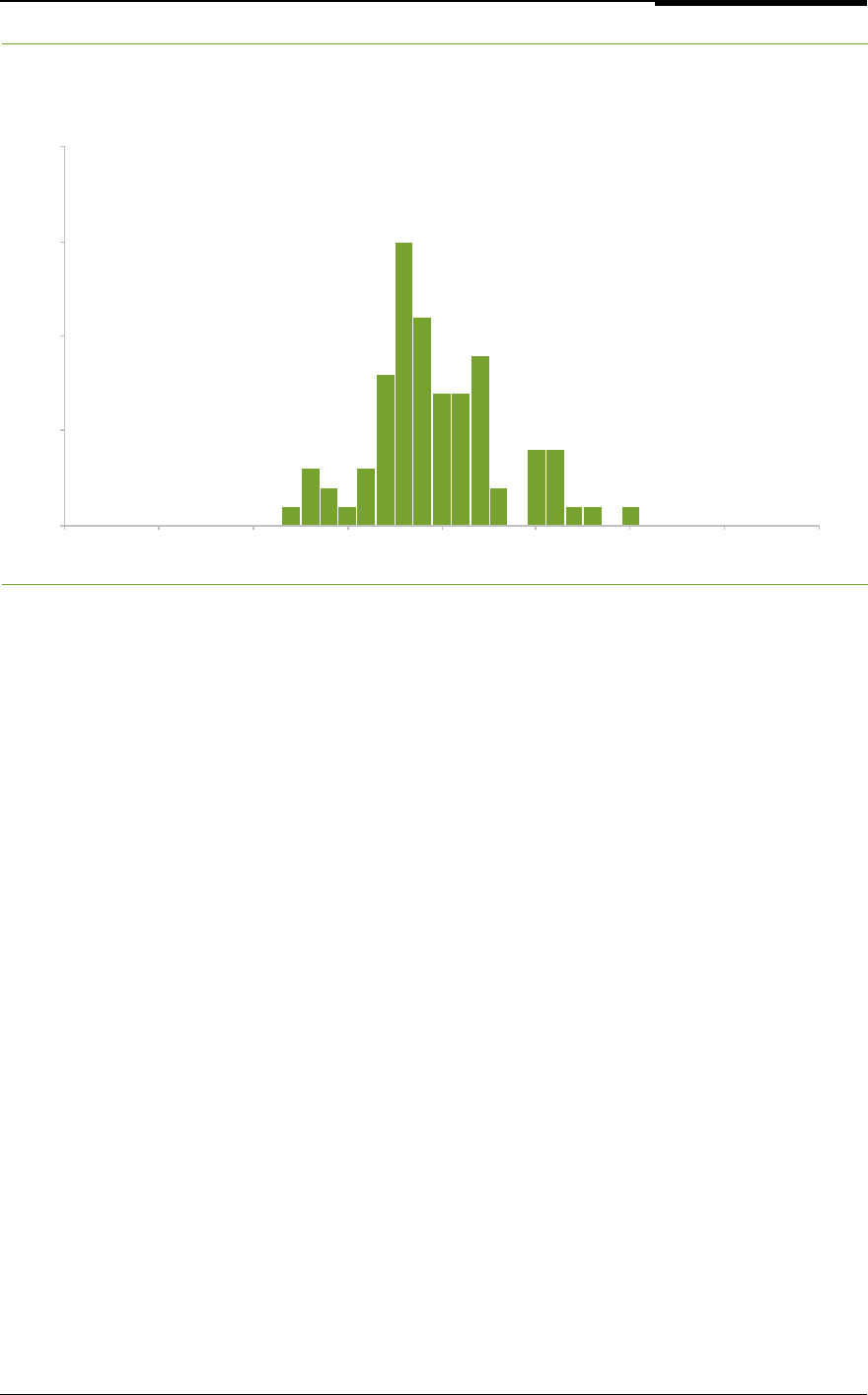

Figures A.7 and A.8 show the distribution of changes over time in the key variable

in

the two data sets — SIH and Census. The model is identified from these changes and the

key empirical question is: are changes in the share of immigrants in total workers

statistically related to labour market outcomes of Australian-born workers over the sample

period? We can see that in both data sets, the changes in the share of migrants is centered

around zero and is fairly small – while we do observe both positive and negative changes,

this will limit our ability to detect any effect of immigration on labour market outcomes.

In the Census, we find that the average proportional change in migrant share (pooling

across the two time periods) is 0.0022. The minimum is -0.07 and the maximum is .10. In

the SIH, the average is slightly negative (-0.0049), the minimum is -0.13 and the maximum

change is 0.18. The migrant share changes calculated from the SIH have a slightly higher

variance than those calculated from the Census. In general, across both data sets, the larger

changes are for the most highly educated groups who saw positive increases in the share of

immigrants over time. The two groups with certificates (year 12 and no year 12) saw the

largest decreases in immigrant share.

Figure A.7 Distribution of migrant share changes between periods: SIH

data

0

5

10

15

20

-0.2 -0.15 -0.1 -0.05 0 0.05 0.1 0.15 0.2

14

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

Figure A.8 Distribution of migrant share changes between periods:

Census data

A.4 Empirical results

We estimate models of the labour market outcomes of Australian-born workers (including

annual earnings, weekly earnings, weekly hours worked, hourly wage rate, labour force

participation, and unemployment rate) against the share of migrants with different

specifications: (i) models that include only the time dummy variables; (ii) models

controlling for all dummy variables including dummies for education groups, for

experience groups, and dummies for time but without any interaction terms; (iii) models

controlling for education, experience, time and the interactions between dummy variables

that allow for changing skill premia over time.

We present weighted regressions using the weights defined as the number of

Australian-born in each education-experience cell for whom the relevant outcome variable

is defined. That is, we weight labour force participation regressions by the native

population, unemployment regressions by the native labour force, and hours and earnings

regressions by the number of natives employed. We also present unweighted estimates for

comparison. In all of our models, we present standard errors that control for clustering on

education-experience cells to allow for serial correlation in the estimates.

The results from SIH data are presented in tables A.1 and A.3 and results from HILDA

wage and earnings data matched to census data for immigrant shares by

experience/education cells are reported in tables A.2 and A.4. In our discussion of these

results we begin with the broad, overarching story coming out of the coefficients, before

turning to individual coefficients that may be of particular interest.

0

5

10

15

20

-0.2 -0.15 -0.1 -0.05 0 0.05 0.1 0.15 0.2

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

15

Empirical results: Survey of Income and Housing

Table A.1 presents the results for the full sample from the SIH. In the first row, we

estimate a model that includes only time dummies and no controls for education or

experience. Row two presents results where we add the controls for education and

experience levels, but no interactions between the two. Row three presents the results when

we add the full set of skill controls including interactions between education and

experience and interactions with time which allow skill premia to vary across time.

Unweighted estimates are provided in row four for comparison.

Table A.1 Estimated values of

from equation (1): SIH, full sample

Log annual

earnings

Log weekly

earnings

Log of wage

rate

Weekly

hours

Participation

rate

Unemployment

rate

Weighted, time dummies only

θ 1.879*** 1.650*** 1.510*** 7.480** 0.240* -0.205***

(0.360) (0.301) (0.231) (2.991) (0.120) (0.055)

Weighted, education, experience and time dummies but no interactions

θ -0.090 -0.086 -0.144** 0.089 0.108 -0.017

(0.143) (0.135) (0.068) (3.124) (0.111) (0.053)

Weighted; education, experience and time dummies and their interactions — preferred estimates

θ 0.175 0.021 -0.077 6.983 0.525** -0.021

(0.154) (0.169) (0.205) (4.190) (0.250) (0.043)

Unweighted; education, experience and time dummies and their interactions

θ .388** 0.179 0.035 8.549*

.464** -0.035

(0.177) (0.186) (0.196) (4.662) (0.207) (0.04)

Note: *,**,*** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% significance level respectively.

The weighted estimates with a full set of shift and interaction dummies (row three) are our

preferred model in all of the tables. We primarily discuss these weighted results.

For models that only include time dummies, we find a positive relationship (and

statistically significant) between immigration and wages (measured as yearly earnings,

weekly earnings or hourly wage) in the sense that more immigration is correlated with

higher wages. Immigration is also correlated with higher labour force participation and

lower unemployment.

For the models that include all dummy variables and their interactions, we find little

statistical relationship between immigration and wages or other labour market outcomes

(participation or unemployment). There does appear to be some small statistical association

16

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

between immigration and a higher participation rate. This association is quite small. If the

share of immigrants goes up by 1 percentage point (from say 20% to 21%), this is

associated with a 0.5 percentage point increase in the participation rate. Recall from

figure A.9 that the typical changes are very small — on the order of one percentage point.

Empirical results: HILDA combined with Census data

The results for the HILDA/Census data are quite similar (table A.2). We find a strong

association between Australian-born labour market outcomes and immigrant shares when

we do not control for different returns to experience and education. Once we include a full

set of dummies, these associations disappear. We find no statistically significant

associations.

Table A.2 Estimated values of

from equation (1): HILDA and Census,

full sample

Log annual

earnings

Log weekly

earnings

Log of wage

rate

Weekly

hours

Participation

rate†

Unemployment

rate†

Weighted, time dummies only

θ

2.016*** 1.821*** 1.686*** 4.682 0.241** -0.244***

(0.404) (0.337) (0.245) (4.193) (0.119) (0.066)

Weighted, education, experience and time dummies but no interactions

θ

0.210 0.455*** 0.243* 6.315 -0.007 -0.015

(0.185) (0.154) (0.130) (6.010) (0.089) (0.058)

Weighted; education, experience and time dummies and th

eir interactions — preferred estimates

θ

0.267 0.752 0.612 11.349 0.074 0.076

(0.666) (0.607) (0.413) (14.997) (0.081) (0.047)

Unweighted; education, experience and time dummies and their interactions

θ

-0.061 0.534 0.622 13.922 0.034 0.061

(0.714) (0.634) (0.476) (14.987) (0.071) (0.038)

Note: *,**,*** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% significance level respectively.

†Calculated from Census; otherwise calculated from HILDA.

Overall, the results show strong evidence for migrant selection. We reach this conclusion

because we observe that when we add no controls (except time dummies), there is a very

strong positive association between labour market outcomes and immigration. This could

lead one to erroneously conclude that immigrants are ‘causing’ positive labour market

outcomes.

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

17

When we control for differential returns to experience and education and changes to those

returns over time (by including the full set of education and experience dummy variables

and their interactions), we find that the positive association disappears. The positive

correlation observed in row 1 of tables A.1 and A.3 is thus ‘spurious’ in that what we are

picking up is that immigrants are associated with high skill levels and labour market

outcomes are also associated with high skill levels. Once we control for this association,

the ‘causal’ effect of immigration on labour market outcomes (in row 3 of tables A.1

and A.3) becomes mostly statistically insignificant. Further, there is not a clear and

consistent story looking at the signs and sizes of the coefficients – some are consistent with

stronger labour market outcomes (higher wages, higher participation rates and hours and

lower unemployment), and some with weaker labour market outcomes.

Thus, migrants are flowing into those skill groups that have the highest earnings and the

best employment opportunities. This is the result of government policy but also of the

decisions by potential migrants, which determine which type of migrant comes to

Australia.

Once we account for the differential returns to experience and education, we find no

evidence across the sample that immigration is associated with worse labour market

outcomes for Australian-born workers. In the SIH data, there is a small statistical

association between immigration and a higher participation rate among Australian-born

workers. This association is small in size and only significant at the 10 per cent level.

Empirical results: Separate estimation by male and female

Tables A.1 and A.2 pooled all individuals. We also re-estimate the models, splitting the

sample by male/female. (See tables A.3 and A.4 for SIH and HILDA/Census,

respectively.) In what follows, unless otherwise specified, we present results from our

preferred specification where we control for a full set of dummies and interactions. The

patterns that we observe in tables A.1 and A.2 — positive selection by immigrants when

we do not control for returns to education and experience and weighted and unweighted

estimates which are roughly similar — are repeated for all of our models. These full results

are available from the authors upon request.

For males, in both data sets, we find no statistically significant association between

immigration and labour market outcomes. In SIH, we find positive associations at the

10 per cent significance level between immigration and hours worked and labour force

participation in the female sub-sample. Using the Census data, we find a positive

association between immigration and the unemployment rate for females. More

immigration seems related to more unemployment. The effect is significant at the 5 per

cent level, but very small and only for females. If the share of immigrants goes up by

5 percentage points, the unemployment rate for females increases by about 0.6 percentage

points. Note that we only find this effect in the Census data. The coefficient for females in

the SIH data is actually negative, although not statistically significant.

18

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

The model of equation (1) imposes a constant response parameter, , across all experience

and education groups. Given the large number of fixed effects in the model, it is not

possible to estimate a model with a parameter that varies by skill group.

It may be that the labour market outcomes of different types of workers have different

responses to immigration in which case the assumption of a constant response parameter

would be incorrect. To test this hypothesis, at least somewhat, we estimate the model for a

sub-population of people with experience less than or equal to 15 years. We again estimate

models where we pool across all individuals as well as separately by male and female.

The results are broadly consistent with what we find in the main sample. For the SIH

(table A.3) the only statistically significant relationship that we find is for females.

Specifically, we find that increased immigration is associated with decreased

unemployment. If the share of immigrants goes up by 5 percentage points, this is

associated with a drop in the unemployment rate for females of about 0.9 percentage

points.

Table A.3 Estimated values of

from equation (1): SIH, selected

sub-samples

Log annual

earnings

Log weekly

earnings

Log of wage

rate

Weekly

hours

Participation

rate

Unemployment

rate

Males only

θ 0.064 0.064 0.068 -0.848 0.131 -0.037

(0.164) (0.181) (0.196) (3.226) (0.101) (0.051)

Females only

θ 0.155 0.153 -0.029 8.112* 0.209* -0.039

(0.184) (0.170) (0.203) (4.803) (0.104) (0.050)

All individuals with 15 years of experience or less

θ 0.247 -0.082 -0.254 3.465 0.175 -0.098

(0.332) (0.445) (0.406) (9.117) (0.207) (0.094)

Males with 15

years of experience or less

θ 0.298 0.240 0.359 -5.202 -0.049 0.033

(0.222) (0.278) (0.398) (3.885) (0.106) (0.087)

Females with 15 years of experience or less

θ 0.071 -0.122 -0.038 7.417 0.100 -0.189*

(0.348) (0.354) (0.586) (7.253) (0.160) (0.099)

Models include full set of time dummies, education and experience fixed effects and full set of interactions

Note: *,**,*** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% significance level respectively.

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

19

In the combined HILDA / Census data (table A.4), we find no relationship between any of

the earnings variables and immigration for this less experienced group. We do find a weak

positive association between immigration and participation in the full sample of less

experienced people. We again find a positive relationship between immigration and

unemployment for females. Note the contrast with SIH where we find a negative

relationship between immigration and unemployment for females.

Table A.4 Estimated values of

from equation (1): HILDA and Census,

selected subsamples

Log annual

earnings

Log weekly

earnings

Log of wage

rate

Weekly

hours

Participation

rate†

Unemployment

rate†

Males only

θ

0.792 1.213 1.166 16.878 0.009 0.037

(0.814) (0.832) (0.704) (16.506) (0.053) (0.039)

Females only

θ

-1.105 -0.486 -0.673 8.443 -0.033 0.112**

(0.784) (0.747) (0.531) (18.539) (0.092) (0.050)

All individuals with 15 years of experience or less

θ

0.038 0.593 0.230 -4.133 0.180* 0.167

(0.432) (0.504) (0.694) (24.168) (0.096) (0.110)

Males with 15 years of experience or less

θ

0.335 0.975 1.020 5.704 0.059 0.083

(0.841) (0.809) (0.735) (26.580) (0.076) (0.079)

Females with 15 years of experience or less

θ

-0.691 -0.370 -0.773 -7.373 -0.002 0.256*

(1.295) (1.259) (0.840) (32.681) (0.101) (0.134)

Models include full set of time dummies, education and experience fixed effects and full set of interactions

Note: *,**,*** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% significance level respectively.

†Calculated from Census; otherwise calculated from HILDA.

Empirical results: Incumbents

Throughout this paper so far, we have compared immigrants (as those born outside

Australia) to those born in Australia. But Australia has a very large stock of immigrants

who, while born outside of Australia, have lived in Australia for a long time. To check if

our results are driven by how we classify individuals, we re-estimate the model comparing

‘incumbents’ to ‘recent immigrants’. We define incumbents as those born in Australia plus

20

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

those who have migrated to Australia more than five years previously. ‘Recent

immigrants’ are now defined as those who migrated to Australia within the last five years.

We estimate the labour market outcomes of incumbents as a function of the share of recent

immigrants in overall population. Weights are now defined based upon the number of

incumbents rather than the number of Australian-born. We only estimate models using the

Census / HILDA data. In the SIH, we do not have precise enough information about year

of arrival in Australia to distinguish between incumbents and recent arrivals. Results for

the full sample are provided in table A.5. We show results without controls and with

controls and weighted and unweighted for comparison with table A.2.

Table A.5 Estimated values of

from equation (1): HILDA and Census,

full sample

incumbents compared to recent immigrants

Log annual

earnings

Log weekly

earnings

Log of wage

rate

Weekly

hours

Participation

rate†

Unemployment

rate†

Weigh

ted, time dummies only

θ

0.142 0.529 0.564 -0.411 0.915*** -0.116

(1.260) (1.116) (0.813) (14.295) (0.235) (0.079)

Weighted, education, experience and time dummies but no interactions

θ

0.211 0.141 -0.028 9.603 0.298** -0.434***

(0.316) (0.296) (0.287) (12.951) (0.132) (0.125)

Weighted; education, experience and time dummies and their interactions

— preferred estimates

θ

0.437 0.519 -0.516 35.527 0.287** 0.101

(1.108) (1.024) (0.654) (31.419) (0.135) (0.095)

Unweighted; education, experience

and time dummies and their interactions

θ

-0.224 -0.049 -0.647 26.260 0.280* 0.111

(1.220) (1.181) (0.917) (32.177) (0.146) (0.084)

Note: *,**,*** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% significance level respectively.

†Calculated from Census; otherwise calculated from HILDA

The only statistically significant effect we find is a positive association between the

participation rate and immigration. If the share of recent immigrants goes up by 5

percentage points, this is associated with an increase in labour force participation of

incumbents of about 1.4 percentage points. When we compare tables A.2 and A.5, it

appears that the effect of selection is much stronger when we compare Australian-born to

all immigrants than when we compare incumbents to recent immigrants. This is a

somewhat counterintuitive result – more recent migrants might be expected to be more

likely to enter strong labour markets. That said, the signs of the coefficients remain broadly

consistent with positive selection.

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

21

We also split the samples by male and female. For males, none of the coefficients are

statistically significant. For females, we find a positive association between recent

immigration and incumbents’ weekly hours.

7

Empirical results: overarching summary

Overall, across all of these estimates, our results indicate that immigration is higher into

those skill groups (defined by education and experience) that have higher wages and better

labour market prospects. This is consistent with immigrants coming to Australia with

knowledge of where returns are high and is also consistent with selective migration

policies.

Once we control for this selection into skill groups by immigrants, there is very little

evidence of any negative labour market effects, in aggregate, on those born in Australia or

the broader group of incumbents resulting from immigration.

Are immigrants and Australian-born workers in same skill groups

comparable?

A key element of our model is the assumption that migrants and Australian-born workers

compete within the same education/experience cells (skill groups). It could be that

experience and education obtained outside of Australia has a lower value in the local

labour market and that in fact migrants are competing with the Australian-born at lower

levels of experience and education. This would mean that we have misclassified some

individuals as competing in one skill group when they should actually be in another, lower

skill group.

First, it is important to note that misclassification by itself poses no threat to our

identification strategy. We identify the effects in the model from changes in the share of

migrants. Mis-classification poses no problem unless the degree of misclassification is also

changing over time.

Nonetheless, it is important to see if immigrants and Australian-born individuals within

skill group cells look similar. In table A.6, we present the three most common occupations

for migrants and natives by education and 10-year experience groupings. The two groups

look very similar, particularly where levels of education are highest. If we think of

anecdotes where overseas-trained doctors are driving taxis in Australia, this might be the

group for whom we would worry the most about misclassification. Yet, the top three

occupations are the same, and in the same order for both immigrants and Australian-born.

Australian-born individuals with higher education are between 6 and 15 percentage points

more likely to be professionals than comparable immigrants, so there is some evidence for

7

These results are available from the authors.

22

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

higher occupational status for the highly educated if they are Australian-born. However,

within our sample there is not evidence of large-scale occupational downgrading by

migrants.

In tables A.7 and A.8, we present the Duncan index of dissimilarity comparing native and

migrant occupational distributions (at the one digit level) holding either education

(table A.7) or experience (table A.8) constant. This index captures the proportion of either

group that would need to change occupations to make the two distributions equal. The

more similar the occupational distributions, the smaller the index. We have highlighted the

smallest values in each row and column.

The results are comforting in the sense that the occupational profiles of immigrants and

natives are most similar within the same education-experience cell, in general. Within

education groups, less experienced migrants look most similar to less experienced natives.

However, highly experienced migrants look more similar to moderately experienced

natives, so there may be some discount placed on overseas experience. Within experience

groups, migrants almost always look most similar to natives with the same education.

Robustness check: broader skill classifications

As a final check on our classification of skill groups, we re-estimate all of the models with

fewer education-experience cells. Some authors have argued that wider skill groups are

better as the assumption of no competition across skill groups is more likely to hold when

skill groups are more broadly defined. We re-estimate all the models using 12 groups —

3 educational groups (high school dropout; university graduates; all others) and

4 experience groups defined by 10 year groupings.

8

The results are quite similar to those already presented.

9

We begin by discussing the effect

of immigration on outcomes for the Australian-born. For the SIH data, the only significant

associations are a positive relationship between hours and immigration and a negative

relationship between unemployment and immigration when we pool male and female

together. The coefficients are 11.8 and -0.08 and are just significant at the 10% level.

When we split the sample by sex we find no statistically significant coefficients. For the

combined HILDA/Census data, we only find a statistically significant association between

immigrants and the participation rate. The coefficient in the pooled sample is 0.40. We find

a statistically significant estimate of .252 for males. We find no effect for females.

8

Figure A.3, the middle 3 educational categories which we have combined together have very similar

average earnings.

9

For this reason we only discuss the results and do not present full tables. These are available from the

authors upon request.

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

23

Table A.6 Three most common occupations by skill group and migrant

/ Australian-born status

Calculated from 2011 Census data

Education

Experience

Top 3 professions (and fraction of workers in occupation)

Migrants

Dropout

1-10 years

Labourers

0.285

Trades

0.191

Machinery

0.139

Dropout

11-20 years

Labourers

0.276

Machinery

0.185

Trades

0.160

Dropout

21-30 years

Labourers

0.235

Machinery

0.171

Clerical

0.154

Dropout

31-40 years

Labourers

0.233

Clerical

0.178

Machinery

0.160

Y12

1-10 years

Sales

0.216

Community

0.183

Labourers

0.175

Y12

11-20 years

Clerical

0.174

Labourers

0.169

Trades

0.119

Y12

21-30 years

Clerical

0.202

Labourers

0.155

Managers

0.149

Y12

31-40 years

Clerical

0.203

Labourers

0.172

Managers

0.153

Cert w/o Y12

1-10 years

Trades

0.410

Community

0.140

Labourers

0.121

Cert w/o Y12

11-20 years

Trades

0.374

Community

0.125

Clerical

0.102

Cert w/o Y12

21-30 years

Trades

0.323

Community

0.136

Managers

0.124

Cert w/o Y12

31-40 years

Trades

0.310

Community

0.133

Managers

0.125

Cert w Y12

1-10 years

Trades

0.256

Community

0.178

Labourers

0.126

Cert w Y12

11-20 years

Trades

0.254

Professionals

0.152

Clerical

0.150

Cert w Y12

21-30 years

Trades

0.226

Professionals

0.169

Clerical

0.152

Cert w Y12

31-40 years

Trades

0.213

Professionals

0.185

Clerical

0.150

Degree

1-10 years

Professionals

0.511

Clerical

0.139

Managers

0.094

Degree

11-20 years

Professionals

0.537

Managers

0.166

Clerical

0.117

Degree

21-30 years

Professionals

0.528

Managers

0.189

Clerical

0.110

Degree

31-40 years

Professionals

0.554

Managers

0.177

Clerical

0.105

Australian born

Dropout

1-10 years

Trades

0.249

Labourers

0.229

Sales

0.155

Dropout

11-20 years

Labourers

0.220

Machinery

0.192

Clerical

0.141

Dropout

21-30 years

Clerical

0.211

Labourers

0.182

Machinery

0.163

Dropout

31-40 years

Clerical

0.239

Labourers

0.177

Machinery

0.151

Y12

1-10 years

Sales

0.255

Community

0.174

Clerical

0.162

Y12

11-20 years

Clerical

0.249

Managers

0.160

Sales

0.130

Y12

21-30 years

Clerical

0.294

Managers

0.191

Sales

0.115

Y12

31-40 years

Clerical

0.293

Managers

0.213

Professionals

0.107

Cert w/o Y12

1-10 years

Trades

0.482

Community

0.105

Clerical

0.094

Cert w/o Y12

11-20 years

Trades

0.386

Managers

0.116

Clerical

0.108

Cert w/o Y12

21-30 years

Trades

0.310

Managers

0.146

Clerical

0.132

Cert w/o Y12

31-40 years

Trades

0.282

Managers

0.143

Clerical

0.139

Cert w Y12

1-10 years

Trades

0.288

Clerical

0.175

Community

0.168

Cert w Y12

11-20 years

Trades

0.247

Clerical

0.186

Managers

0.147

Cert w Y12

21-30 years

Professionals

0.209

Clerical

0.179

Managers

0.175

Cert w Y12

31-40 years

Professionals

0.283

Managers

0.180

Clerical

0.161

Degree

1-10 years

Professionals

0.655

Managers

0.112

Clerical

0.101

Degree

11-20 years

Professionals

0.601

Managers

0.199

Clerical

0.096

Degree

21-30 years

Professionals

0.621

Managers

0.212

Clerical

0.083

Degree

31-40 years

Professionals

0.643

Managers

0.198

Clerical

0.077

24

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

Table A.7 Duncan index of dis-similarity for Australian-born and

immigrant workers calculated from 2011 Census data

holding education constant

Experience of corresponding immigrant group

Education

-experience of native group 1-10 years 11-20 years 21-30 years 31-40 years

High school dropouts

1-10 years

0.097

0.182

0.197

0.209

11-20 years

0.173

0.097

0.040

0.063

21-30 years

0.240

0.195

0.107

0.081

31-40 years

0.261

0.225

0.137

0.108

Year 12

1-10 years

0.099

0.244

0.266

0.282

11-20 years

0.271

0.148

0.104

0.121

21-30 years

0.332

0.209

0.169

0.188

31-40 years

0.354

0.222

0.183

0.197

Certificate

(w/o Year 12)

1-10 years

0.082

0.122

0.175

0.186

11-20 years

0.108

0.057

0.080

0.091

21-30 years

0.172

0.094

0.041

0.035

31-40 years

0.195

0.119

0.056

0.040

Certificate (w Year 12)

1-10 years

0.114

0.132

0.168

0.199

11-20 years

0.198

0.080

0.078

0.101

21-30 years

0.294

0.150

0.108

0.105

31-40 years

0.355

0.211

0.163

0.146

Degree

1-10 years

0.161

0.122

0.138

0.116

11-20 years

0.195

0.096

0.083

0.069

21-30 years

0.228

0.130

0.116

0.102

31-40 years

0.236

0.138

0.124

0.110

Numbers in table indicate the proportion of individuals who would have to change occupation to make the

occupational distribution identical for two groups. Highlighted cells are the lowest – indicating the most

similar distributions – in their row or column.

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

25

Table A.8 Duncan index of dis-similarity for Australian-born and

immigrant workers calculated from 2011 Census data

holding education constant

Education of corresponding immigrant group

Education-experience of native

group

High

school

dropout Year 12

Certificate

(w/o

Year 12)

Certificate

(w Year 12) Degree

1-10 years

High school dropout

0.097

0.252

0.246

0.200

0.585

Year 12

0.324

0.099

0.305

0.187

0.488

Certificate (w/o Year 12)

0.328

0.399

0.082

0.227

0.550

Certificate (w Year 12)

0.353

0.280

0.220

0.114

0.427

Degree

0.711

0.640

0.668

0.622

0.161

11-20 years

High school dropout

0.097

0.155

0.346

0.332

0.568

Year 12

0.345

0.148

0.331

0.270

0.441

Certificate (w/o Year 12)

0.315

0.275

0.057

0.175

0.537

Certificate (w Year 12)

0.387

0.223

0.225

0.080

0.422

Degree

0.685

0.566

0.632

0.536

0.096

21-30 years

High school dropout

0.107

0.112

0.349

0.346

0.556

Year 12

0.324

0.169

0.325

0.275

0.421

Certificate (w/o Year 12)

0.319

0.241

0.041

0.119

0.492

Certificate (w Year 12)

0.374

0.258

0.242

0.108

0.333

Degree

0.696

0.594

0.623

0.524

0.116

31-40 years

High school dropout

0.108

0.096

0.354

0.346

0.564

Year 12

0.304

0.197

0.324

0.275

0.447

Certificate (w/o Year 12)

0.324

0.252

0.040

0.103

0.493

Certificate (w Year 12)

0.388

0.306

0.283

0.146

0.271

Degree

0.703

0.614

0.622

0.512

0.110

Numbers in table indicate the proportion of individuals who would have to change occupation to make the

occupational distribution identical for two groups. Highlighted cells are the lowest — indicating the most

similar distributions — in their row or column.

Interestingly, we find stronger effects when we consider broad skill groupings for

incumbents, but the results are inconclusive on the question as to whether immigration

leads to stronger or weaker labour market outcomes for incumbents (See table A.9.) We

find a negative association between incumbent wages and the fraction of recent

immigrants. We find statistically significant positive associations between immigration and

weekly hours worked and participation. The fraction of recent immigrants is significant at

the 5% level for participation, but only at the 10% level for wages and weekly hours. The

wage and hours effects are fairly strong. If the share of recent immigrants goes up by 1

26

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

percentage point, this is associated with a drop in wages of 2.6 per cent, an increase in

weekly hours of 32 minutes and an increase in the participation rate of one-half of one

percentage point.

When we split the sample by sex (table A.9) we again find mixed results. For males we

find a positive association between recent migration and the participation rate but also a

positive association with the unemployment rate. The wage and hours effects from the

pooled sample are concentrated amongst female workers — for men the effects are smaller

and not statistically different from zero.

Table A.9 Estimated values of

from equation (1): HILDA and Census

(incumbents compared to recent immigrants); Broad

experience groups and education categories

3 education categories and 4 experience categories

Log annual

earnings

Log weekly

earnings

Log of wage

rate

Weekly

hours

Participation

rate†

Unemployment

rate†

All incumbents

θ

0.618 0.307 -2.587* 53.607* 0.580** 0.257

(1.104) (1.082) (1.243) (29.675) (0.235) (0.153)

Males only

θ

0.430 0.371 -0.266 33.002 0.366* 0.306**

(1.944) (2.170) (1.596) (50.258) (0.186) (0.120)

Females only

θ

1.226 0.444 -5.471*** 91.568*** 0.440 0.130

(1.999) (1.815) (1.452) (24.716) (0.338) (0.340)

Models include full set of time dummies, education and experience fixed effects and full set of interactions

Note: *,**,*** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% significance level respectively.

†Calculated from Census; otherwise calculated from HILDA.

It is important to note that the negative wage effect in the pooled sample is also very

fragile and driven by one skill group: degree holders with 1-10 years of experience. If we

add a dummy variable for that group (or drop them from the analysis), the coefficient on

immigrant share in the wage regression becomes positive, 0.5376, but insignificant.

Between 2001 and 2011, this group of individuals had lower wage growth than expected

but this could plausibly be for other reasons, such as differential effects of the Global

Financial Crisis or the mining boom across education-experience groupings.

10

10

For example, either the mining boom or Global Financial Crisis could have plausibly eroded the wages of

young university graduates, relative to other workers with little experience or university graduates well

into their careers through rapid wages growth for trades or limited employment growth in traditionally

well-paid graduate jobs.

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

27

A priori, it is difficult to say whether the more narrow skill groups or the broader skill

groups provide better estimates. Comparing table A.2 to table A.9, we can see that the

standard errors are two to three times larger when we use the broader groups and the

incumbent sample. The broader groups will provide more imprecise estimates and

potentially more volatile estimates since we are estimating on a much smaller effective

sample size. The narrower groups will give biased estimates if skill groups are too

narrowly defined and if there is leakage and competition across skill groups. As others in

the literature have pointed out, the results do depend upon the definition of skill groups.

A.5 Discussion and conclusion

In this paper we use a simple and data driven approach to address whether or not the labour

market outcomes of the Australian-born and incumbents are related to patterns of

migration. We do this by constructing skill groups which are defined by education and

years of (potential) experience. We look at whether changes in the share of immigrants in

these cells over time is related to changing labour market outcomes for the Australian-born

and incumbents. We control for a variety of fixed effects as well as macroeconomic

conditions and we allow the return to skills to vary over time.

Overall, and looking across the full suite of our results, we find little evidence that the

labour market outcomes of Australian-born workers are negatively related to immigration.

The few statistically significant associations we do find are inconclusive, and cover both

stronger and weaker labour market outcomes. They may arise simply from statistical

chance or reflect the influence of omitted variables on relative labour market outcomes of

education-experience cells over time. Moreover, these associations are economically small

and only just statistically significant, so the evidence is scant. Our results are consistent

across two very different data sets.

We do find some negative effects of recent migrants (those who arrived in Australia in the

last five years) on employment and wage of incumbents (Australian-born and immigrants

who have resided in Australia for more than five years) when we consider very broadly

defined skill groups. However, we also find positive associations between recent migration

and weekly hours and labour force participation of incumbents.

The approach that we use has an advantage over approaches that use the uneven

geographical spread of immigrants to identify the impact of immigration on labour market

outcomes. In those approaches, geographical labour markets are assumed to be distinct and

movement between labour markets which might be driven by differences in employment

opportunities and wages are ruled out. In Australia, this looks like a very bad assumption

given the large flows of workers from one state to another which we observed during the

mining boom which took place during our data period, 2001–2011.

28

MIGRANT INTAKE INTO

AUSTRALIA – TECHNICAL SUPPLEMENT A

The disadvantage of our approach is that we assume that each skill group (defined by

education and experience) is an individual labour market and that there is no

substitutability of workers across different labour markets. Specifically, the approach is

assuming that the arrival of immigrants in one skill group is not causing Australian-born or

incumbent workers to move to competing in another skill group. Given that skill groups

are defined on relatively immutable categories, education and potential experience, this

seems less problematic than the geographical assumption.

Our results are dependent both upon the immigration policies in place during the period

2001–2012 and the overall economic conditions. As we are estimating over a period of

very robust economic growth, it is perhaps not surprising that we find very little negative

impact of immigration on natives and incumbents. It could be that in periods of slow

growth or contraction there are negative effects, but we would not be able to identify these

in our data. Given that our approach is non-parametric and data-driven, our results are

dependent upon policy settings. The results do not give any insight into how different

policies might affect the relationship between immigration and labour market outcomes of

the Australian-born and incumbents.

One reason why we may fail to find statistically significant results is that the amount of

variation in immigrant shares in our data is pretty small. Recalling figures A.9 and A.10,

most of the skill groups show little or no change in the proportion of immigrants over time.

A longer time window and more variability in immigration would assist in identification

— as available in the original Borjas (2003) paper — but we do not currently have either

of these things.

Our data does not account for short-term migrants. They are absent in the census data by

construction. In the SIH, they would only be counted if they were living in private

dwellings. If short-term migrants are living in hostels or other non-private dwellings, they

will not be in our data. While this group may be important for certain low-skill jobs in the

economy, the results across all skill groups should not be substantially impacted by their

absence.

Throughout, we have discussed changes in the percentage of migrants in skill groups as

being related to in-flows of migration. But, they can also be related to outflows. Immigrant

shares in skill groups can drop if Australian-born workers are out-migrating even in the

absence of any change in immigration. Our intuition, again, is that this is not an important

determinant of the results. Out-migration has been important in highly skilled groups in

Australia, but less so during the economic boom of the 2000s. For most groups,

in-migration dominates out-migration and it is this effect that we are mostly capturing.

Despite these caveats, the paper provides important new information about the relationship

between immigration and the labour market outcomes of the Australian-born and

incumbents at an aggregate level. If there were strong negative effects, the approach used

here should reveal a more consistent picture — in the signs, sizes and statistical

significance of the coefficients. The fact that we find associations with both stronger and

weaker labour market outcomes, with the few results that are statistically significant

IMMIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA AND THE LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES

29

relatively sensitive to assumptions such as the classification of skill groupings, suggests

that, at least at the level of the overall economy and the vast majority of workers,

immigration does not appear to have been a major factor in the labour market outcomes of

the Australian-born and previous immigrant cohorts over the period studied.

References

Bond, M., and Gaston, N. 2011, ‘The impact of Immigration on Australian-born workers:

An assessment using the National Labour Market Approach’, Economics Papers, vol.

30, no. 3, pp. 400–13

Borjas, G. J. 2003, ‘The Labor Demand Curve Is Downward Sloping: Reexamining the

Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol.

118, no. 4, pp. 1335–74.

Borjas, G. J. 2006, ‘Native Internal Migration and the Labor Market Impact of

Immigration’, Journal of Human Resources, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 221–58.

Duncan, O. B. and Duncan, B. 1955, ‘Residential Distribution and Occupational

Segregation’, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 60, no. 5, pp. 493–503.

Friedberg, R. M., and Hunt, J. 1995, ‘The Impact of Immigrants on Host Country Wages,

Employment and Growth’, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, pp. 23–44.

Manacorda, M., Manning, A., and Wadsworth, J. 2012, ‘The Impact of Immigration on the

Structure of Wages: Theory and Evidence from Britain’, Journal of the European

Economic Association, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 120–51.

Ottaviano, G. I., and Peri, G. 2012, ‘Rethinking the Effect of Immigration on Wages’,

Journal of the European Economic Association, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 152–97.

Sinning, M. and Vorell, M. 2011, ‘People’s Attitudes and the Effects of Immigration to

Australia’, Ruhr Economic Papers 0271, Rheinisch-Westfälisches Institut für

Wirtschaftsforschung, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Universität Dortmund, Universität

Duisburg-Essen.

Smith, J. P., and Edmonston, B. (eds.) 1997, The new Americans: Economic, demographic,

and fiscal effects of immigration, National Academies Press.