Labour Market Edition

March 2024

© Commonwealth of Australia 2024

ISSN: 2653-6196

This publication is available for your use under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence,

with the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, the Treasury logo, photographs, images,

signatures and where otherwise stated. The full licence terms are available from

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode.

Use of Treasury material under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence requires you to

attribute the work (but not in any way that suggests that the Treasury endorses you or your use of

the work).

Treasury material used ‘as supplied’.

Provided you have not modified or transformed Treasury material in any way including, for example,

by changing the Treasury text; calculating percentage changes; graphing or charting data; or deriving

new statistics from published Treasury statistics – then Treasury prefers the following attribution:

Source: The Australian Government the Treasury.

Derivative material

If you have modified or transformed Treasury material, or derived new material from those of the

Treasury in any way, then Treasury prefers the following attribution:

Based on The Australian Government the Treasury data.

Use of the Coat of Arms

The terms under which the Coat of Arms can be used are set out on the Department of the

Prime Minister and Cabinet website (see https://www.pmc.gov.au/honours-and-

symbols/commonwealth-coat-arms).

Other uses

Enquiries regarding this licence and any other use of this document are welcome at:

Manager

Media Unit

The Treasury

Langton Crescent

Parkes ACT 2600

Email: media@treasury.gov.au

In the spirit of reconciliation, the Treasury acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of country

throughout Australia and their connections to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to their

Elders past and present and extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour Market Edition | iii

Contents

Foreword .......................................................................................................................... iv

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia ........................................... 1

1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 2

2 Matching efficiency in the Australian labour market ..................................................................................... 3

3 Skill level variation in labour market tightness and occupation movements ................................................. 7

4 Regional variations in labour market tightness and matching by skill level ................................................. 15

References ............................................................................................................................................................. 27

Exploring community resilience in Australia .................................................................... 29

1 Defining resilience ........................................................................................................................................ 30

2 Conceptualising the value of resilience ........................................................................................................ 31

3 Resilience frameworks .................................................................................................................................. 32

4 Measuring resilience .................................................................................................................................... 35

5 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................... 40

Appendix ............................................................................................................................................................... 41

References ............................................................................................................................................................. 42

Employment behaviour of firms reliant on temporary migrants ....................................... 45

1 Temporary migrant workers ......................................................................................................................... 46

Incentives for secondary earners and income support recipients ..................................... 55

Address to the Policy Research Conference .......................................................................................................... 55

1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 56

2 History of employment white papers ........................................................................................................... 57

3 The 2023 Employment White Paper ............................................................................................................ 58

4 The barriers framework ................................................................................................................................ 60

5 Secondary earners ........................................................................................................................................ 61

6 Income support recipients ........................................................................................................................... 64

7 Policy options ............................................................................................................................................... 66

8 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................... 67

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Foreword | iv

Foreword

Steven Kennedy

Broader indicators of labour market spare capacity are needed to measure progress towards

sustained and inclusive employment. Nearly 3 million people want to work, or to work more hours

than they do. The articles in this edition of the Round Up explore 4 aspects that are central to

addressing structural barriers in Australia’s labour market and meeting long-term labour market

objectives: geographical barriers, the net zero transformation, migration, and incentives.

As Australia faces changing skills needs across regions, improving job matching efficiency can support

greater economic output for a given level of labour supply and demand for workers. ‘Labour market

matching across skills and regions in Australia’ shows that matching efficiency has improved in recent

years, but that variations across labour market regions and skills can result in different labour market

outcomes across the country.

The net zero transformation is generating significant shifts across Australia’s economy and its regions.

The article ‘Exploring Community Resilience in Australia’ outlines the importance of resilience to

recover from and adapt to shocks. Not surprisingly, communities closer to major cities and regional

centres have higher levels of resilience compared to more remote communities.

The article ‘Employment behaviour of firms reliant on temporary migrants’ discusses how businesses

reliant on temporary migrants responded to Australia’s international border closure. The article finds

that businesses with higher temporary migrant workforces experienced greater job losses than

businesses less reliant on temporary migration. Businesses sought to find alternative labour sources

and to use labour more intensively. Observed increases in monthly average pay were likely driven by

increases in hours worked, and potentially due to increased hourly wages. Once borders reopened,

businesses responded by hiring more temporary migrants, with average pay of domestic workers

increasing by more than temporary migrants.

The final article is my address to the inaugural Treasury Policy Research Conference, which supported

the development of the 2023 Employment White Paper. The speech, ‘Incentives for secondary

earners and income support recipients’, finds that the tax-transfer system can shape decisions to

participate in the labour market, including decisions about how many hours to work. Secondary

earners and income support recipients may face reduced incentives to participate in the labour

market as fully as they may wish to. There are trade-offs between adequacy of government

payments, cost to taxpayers, and incentives to participate – all of which are important considerations

in the context of expanding labour market opportunities.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 1

Labour market matching across skills and regions

in Australia

Will Mackey

1

Summary

This paper explores patterns of searching and matching in the Australian labour market. It first

estimates matching efficiency between 2004 and 2023 at the national level, showing 3 distinct

periods: a more efficient labour market leading up to the Global Financial Crisis; a decade-long

slump from 2010 with low matching efficiency and growing rates of long-term unemployed; and

a period of instability from 2020 when an unprecedentedly tight labour market was met with

strong job finding rates causing aggregate matching efficiency to rise throughout 2022.

Unemployed people were more likely to find work in 2022 than at any point since data began in

2004. This was true for short, long and very long-term unemployed people.

One source of mismatch – skill mismatch – is examined to show that higher skilled workers tend

to experience tighter labour markets and lower levels of within-skill mismatch compared to

lower-skilled groups. Between-skill employment mismatch means that higher skilled workers can

crowd out lower-skilled workers and job seekers.

The national labour market is then divided along regional and skill level lines to show

heterogenous conditions in 111 local labour markets. By controlling for some sources of

geographic and skill mismatch, this analysis demonstrates that mismatch remains within

region-skill labour market cells.

1 Thanks to Professor Jeff Borland, Stephanie Parsons, Josh Hickson, Nathan Deutscher, Omid Mousavi,

Phoebe Wilk, Oscar Lane, as well as other staff from Treasury and Jobs and Skills Australia, and

participants at the Australian Conference of Economists, for their thoughtful feedback and supporting

analysis for this paper. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those

of the Australian Treasury or the Australian Government.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 2

1 Introduction

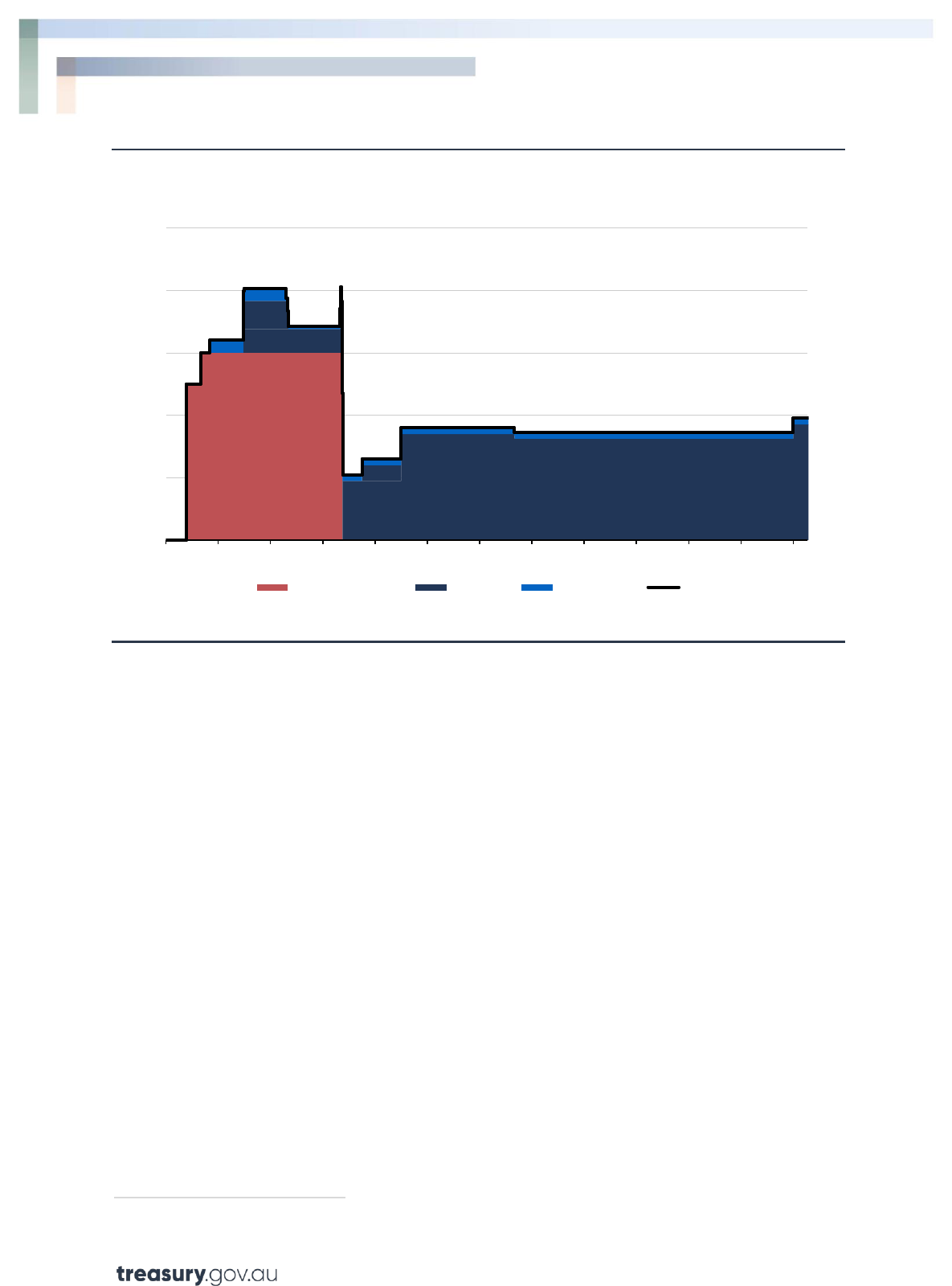

The Beveridge Curve is the relationship between job vacancies and job seekers in a labour market.

A tighter labour market indicates that there are more vacancies for each unemployed person, and a

looser labour market means there are more unemployed people for each vacancy. Chart 1.1 shows

Australia’s Beveridge Curve from the late 1970s to May 2023. There was high unemployment and low

vacancies in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The labour market tightened into the 2000s except for a

period of loosening at the onset of the Global Financial Crisis. The 2010s were relatively stable with

the vacancy rate of 1–2 per cent and unemployment rate between 4.5–6.5 per cent. With the

COVID-19 pandemic shock from 2020, unemployment grew temporarily before vacancies rose to the

highest level on record.

While these shifts reflect cyclical features of the labour market over time, how well job seekers and

jobs are ‘matched’ has an important role. Matching efficiency reflects the labour market’s ability to

match individuals to jobs, which can be limited by disconnects between the skills and location of

potential workers, and the requirements, renumeration, and location of available jobs. A more

efficient labour market will have lower levels of unemployment for the same level of labour demand.

Improving matching efficiency drives down the natural rate of unemployment and reduces skills

shortages in the economy.

Improving matching efficiency in the labour market means Australia can generate more economic

output for a given level of available workers and demand for labour. This paper first uses detailed

vacancy, job seeker and matching data to explore changes in labour market matching efficiency in

Australia between 2004 and 2023 for a range of job seeker groups. The paper then explores skill level

variation in labour market tightness and looks at occupation transitions within and between skill

groups. The final section adds a regional lens to illustrate the heterogeneity of local labour markets

that can coexist across Australia.

Chart 1.1 The Beveridge Curve

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Job Vacancies and ABS Labour Force Survey. Seasonally adjusted figures.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 3

2 Matching efficiency in the Australian labour market

Job vacancies and people looking for employment can coexist in the labour market. For example, a

skills mismatch can occur when a job seeker does not have the skills required for an available job, or

the job does not offer the required conditions or renumeration.

2

A geographic mismatch occurs when

the vacancy and job seeker are in different places and the job seeker is unable or unwilling to move.

Chart 2.1 Unemployment and

vacancy rates

Chart 2.2 Next-quarter job finding rate of

unemployed people

Source: ABS Labour Force Survey; ABS Job Vacancies.

Note: Original series. Vacancy rate interpolated

between 2008–09.

Source: ABS Labour Force Survey.

Note: Four quarter rolling average.

Matching efficiency describes the rate at which people seeking work are matched to vacant jobs in a

labour market.

3

Poor matching efficiency reflects disconnects between the preferences, skills and

location of potential workers, and the requirements, location, and renumeration of available jobs.

A more efficient labour market will have lower rates of unemployment for a given level of vacancies.

Improving matching efficiency in the labour market lowers the natural rate of unemployment,

reduces labour and skills shortages, and increases potential output.

While matching efficiency is not directly measured in the economy, it can be estimated from

measures of job vacancies, job seekers and job finders. Job vacancies are a measure of labour

demand. The ABS Job Vacancies series counts vacancies available for immediate filling, and the series

is correlated with near-term future employment growth. The vacancy rate was the highest on record

in 2022, almost double previous peaks (Chart 2.1).

2 A more detailed conceptualisation of labour market skills and skills shortages are outlined in

Richardson (2007).

3 The Beveridge Curve is the relationship between job vacancy and job seeker rates. Key Beveridge Curve

concepts are also explained in Figura and Waller (2022); Jobs and Skills Australia (chapter 5, 2021);

Anh and Crane (2020); Consolo and de Silva (2019); Borland (chapter 11, 2011).

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 4

Job seekers are all people who are seeking work. It is usually measured by the unemployment rate,

which is near a historic low (Chart 2.1). The ratio of vacancies to job seekers in a given period is a

measure of labour market tightness. A tighter labour market indicates there are more vacancies for

each unemployed person, and a looser labour market means there are more unemployed people for

each vacancy. Job finders are people who have a job in the current period and were seeking a job in

the previous period (Chart 2.2).

2.2 Unemployed matching efficiency

This paper measures matching efficiency over time using the job finding rate of unemployed people

relative to what would have been expected based on current labour market tightness (the ratio of

vacancies and unemployed). If job finding rates are unusually high (low), matching efficiency is

considered to be similarly high (low). This approach follows Consolo and de Silva (2019), which is

explored in more detail in Appendix A.

Matching efficiency of unemployed job seekers was high in the pre-GFC period between 2004 and

2009 (Chart 2.3). This period had decreasing unemployment, rising job vacancies, and high

job-finding rates for short-term unemployed. Job-finding rates were 1–3 percentage points higher

than expected for the level of labour market tightness. This period saw lower numbers of long-term

unemployed, who tend to have about half the job finding probability of short-term unemployed

(Chart 2.4).

Chart 2.3 Matching efficiency Chart 2.4 Job finding probability

Matching efficiency relative to long-run average Share unemployed who find work in the next month

Source: Treasury analysis, see Appendix A. Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Labour Force microdata.

Note: Four quarter average. Note: Four quarter average. Very short-term unemployed

is less than 4 weeks; short is 1–12 months;

long-term is >12 months.

Matching efficiency was low between 2010 and 2019. Labour market tightness had a partial rebound

after falling in 2009, but job finding rates remained below pre-GFC peaks across all unemployment

groups. Despite increasing labour market tightness from 2015, job-finding probabilities remained

relatively low. This was driven by lower job-finding rates of long-term unemployed, which made up

a larger share of the unemployed pool. Matching efficiency has been improving since 2019.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 5

Matching efficiency started improving before the onset of the pandemic. Irregular labour market

conditions during 2020 caused measured matching efficiency to be unstable. A tight labour market in

the recovery from the pandemic has been matched by rising job-finding rates for unemployed

people. Unemployed people were more likely to find work in 2022 than at any point since data began

in 2004. This was true for short, long, and very long-term unemployed people.

2.3 Matching trends are clearer when more job seekers are

considered

People classified as unemployed are not the only people who seek and find work.

4

In addition to

unemployed job seekers, there are job seekers who are not in the labour force (NILF). These are

people who are not classified as unemployed but can be actively, passively, or not seeking

employment when previously surveyed. These NILF sub-groups are identified using ABS Labour Force

microdata (see Appendix A).

The first extension expands the scope of job seekers to include all non-working job seekers

(Chart 2.5).

Chart 2.5 Matching efficiency with

non-working job seekers

Matching efficiency relative to long-run average

Chart 2.6 Matching efficiency with all

job seekers

Matching efficiency relative to long-run average

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Labour Force and ABS

Job Vacancies. See Appendix A.

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Labour Force and ABS

Job Vacancies. See Appendix A.

When including all non-working job seekers this analysis finds better matching efficiency rates

between 2009–2013, driven by higher rates of NILF job seekers finding employment. This trend

reversed in subsequent years, pushing matching efficiency lower.

4 About twice as many people move from being outside the labour force to employment each period than

move from unemployed to employed. Capturing this group provides a fuller picture of matches and job

searchers in the Australian labour market.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 6

Employed job seekers – workers who are looking for their next job – are also a large source of new

matches in the economy and can be identified using ABS Labour Force microdata. Adding employed

job seekers, the working and non-working matching efficiency rates were stronger before 2010, and

weaker between 2010 and 2021 (Chart 2.6). This follows trends in job-to-job transitions in the labour

force, which were high and rising until 2009. They then remained persistently low until recovering

from the end of 2021.

5

Trends in matching efficiency are relatively clear. Matching efficiency in the Australian labour market

started to improve in 2022 after a decade-long slump from 2008–2021. This means that unemployed

are finding work faster on average, after accounting for the time of year, vacancy rate and

unemployment rate, demonstrating that businesses are doing a better job at finding new employees

among the available pool of workers. Increased matching efficiency has been driven by all job seeker

groups – unemployed, NILF and employed. Two additional components of labour market matching –

skills and geography – will be explored in following sections.

5 Treasury analysis of ABS Labour Force microdata. See Deutscher (2019) for further discussions of

job-to-job transitions.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 7

3 Skill level variation in labour market tightness and

occupation movements

Analysis of aggregate levels of labour demand (job vacancies) and labour supply (job seekers) is

useful for identifying cyclical trends at the national level. However, the Australian labour market is not

a single, homogenous market. For example, a nurse vacancy in Perth is unlikely to be filled by an

unemployed construction labourer in Cairns, and high unemployment rates of construction labourers

in Cairns are unlikely to fall by hiring more nurses in Perth. This section explores skill level and

occupational labour market matching.

3.1 Exploring skilled labour markets within Australia

The identification of specific labour markets can help us understand sources of mismatched supply

and demand across skill and geographic lines and inform labour market policy decisions. To explore

the labour markets that exist beneath the aggregate requires measuring job vacancies and job

seekers along common dimensions, when:

• Vacancies only have characteristics associated with a particular job, such as an occupation, an

industry, a location and an advertised wage, and

• Job seekers have characteristics only associated with a person, such as: age, sex, a level and field

of education, a location of residence, and – for those who have been recently employed – an

occupation and industry of their previous job.

This analysis uses a job vacancy’s occupation and individual job seeker education level and previous

occupation to explore labour supply, demand, and matching levels by skill levels.

6

Three skill

groupings are used – low, middle and high – which correspond to occupation skill and education

levels. The exact methodology is outlined in Appendix B.

This classification allows for people working in high (or middle) skill occupations to be classified as

high (or middle) skill workers, regardless of their education, to reflect skills developed through

workforce experience. The inclusion of education allows for people without a current or previous

occupation, such as new entrants to the workforce or those coming back from extended periods of

leave or long-term unemployment, to be classified by their education level. This approach means that

every person in the labour force can be assigned a skill level.

7

However, due to data limitations before

August 2015, this analysis is restricted to 2016 onwards.

Applying these skill level groupings to job vacancies and unemployed people in Australia shows

distinct characteristics of high, middle and low-skill labour markets compared to the aggregate.

6 This definition of ‘skill’ is common in the literature and is used by the ABS to form its occupational skill

level framework: ABS (2022). However, this definition of skill does not include or measure the full range of

skills and abilities required by occupations, or for specific jobs within occupations, or those performed by

individuals within their job. Jobs and Skills Australia (2023) provides detailed descriptions of specific skills

that are required for individual occupations in its Australian Skills Classification. See Richardson (2007) for

a detailed discussion of labour market skills.

7 Alternative approaches that rely solely on a person’s previous occupation to determine their skill level are

unable to classify a significant share of the job seeker pool, particularly long-term unemployed and new

entrants to the workforce.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 8

Chart 3.1 shows unemployment rates and vacancy rates for each labour market. In the aggregate

labour market (Panel A), as explored in Section 1, the vacancy rate rose slightly between 2016 and

2019, before dipping in 2020 with the onset of COVID-19. From mid-2020, vacancies rebounded

before surpassing previous levels and now sit at about 3.5 per cent of labour demand (employment

plus vacancies). The unemployment rate has moved broadly inversely to the vacancy rate.

The high-skill labour market (Panel B) tends to be tighter than the aggregate. Demand for high-skill

occupations followed a broadly similar path to the aggregate trend, with a slightly lower vacancy rate

(less than 2 per cent) before increasing to 2.3 per cent at the beginning of 2023. The high-skill group

tends to have low unemployment rates, from about 3.5 per cent between 2016 and 2019 to less than

2 per cent in 2023. At the beginning of 2023 there were more vacancies for high-skill jobs than there

were job seekers with high-skill occupations. However, low unemployment rates may overstate the

level of matching efficiency in the high-skill labour market, as many people are employed in lower-

skilled occupations (explored in the next section).

The middle-skill labour market (Panel C) is persistently looser than the high-skill group, with higher

unemployment and marginally lower labour demand. However, the middle-skill labour market has

tightened significantly over the past 2 years, in line with the aggregate labour market.

The low-skill labour market (Panel D) has higher rates of unemployment and higher rates of

vacancies. The low-skill labour market has tightened significantly since mid-2020, with declining

unemployment rates and rising vacancy rates. But within-skill level mismatch remains high, with

about 7 per cent of the labour force unable to be matched to available jobs. In addition, low-skill job

seekers also compete with some higher skilled job seekers, as explored in the next section.

Chart 3.1 Unemployment and vacancy rates by skill group

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, ABS Job Vacancies, JSA Internet Vacancy Index.

See Appendix B.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 9

3.2 Skill level mismatch of workers can ‘crowd out’ lower-skill

workers

Some degree of skill level mismatch will always exist in the labour force. Over education – where a

worker is in an occupation that does not require their level of education – has increased alongside

rising educational attainment. Sometimes people optimally choose a job that is different to their level

of education and training, reflecting the personal preferences of workers. Other times it is

undesirable, caused by temporary and structural factors that can have flow-on effects to others in the

labour force.

Skill level misallocation may hint at some labour market challenges

Labour market tightness in the high-skill market sits alongside apparent between-skill mismatch.

The mismatch between a worker’s education level and their occupation level is significant. Between

2016 and 2023, about 30 per cent of high-skill workers were employed in occupations classified as

middle and low-skill. This is consistent with other research on over education in the Australian labour

market.

8

These occupations were often lower-skilled health and clerical or administrative roles

(Chart 3.2). Over 40 per cent of middle-skill workers were employed in low-skill occupations,

particularly as machinery operators and labourers.

Skill level mismatch can be the consequence of a more educated workforce. There has been

significant growth in bachelor and postgraduate degree attainment over the past 40 years. About

40 per cent of 25 to 34-year-olds had a bachelor’s degree or above in 2020 (up from 10 per cent in

1980).

9

Over education can be temporary or reflect other compensating factors, such as location or

flexibility or lower pressure jobs.

Skills depreciation can also drive apparent skill level mismatch. The skills demanded within some

occupations can change quickly.

10

Workers who spend time away from the workforce or from a

particular occupation can find themselves without the skills now required for their job, despite having

the required level of education.

Job skill misclassification can occur when a particular job within an occupation requires more

education than is typically required for that occupation. For example, the education and training

requirements for a Hospitality Manager can vary according to the size and complexity of the

organisation.

Geographic mismatch, where appropriately skilled jobs are not available in the region, can also lead

job seekers to take up lower-skilled work. This type of mismatch is explored in Section 4.

8 Heath (Graph 11, 2020). While education and occupation skill level definitions of skills mismatch are

presented in this paper, Treasury analysis of HILDA data also finds that about 25 per cent of people with

post-secondary qualifications self-report that their skills are not well utilised in their current job.

9 Rates of vocational attainment have remained flat over this period at about 35 per cent. Norton,

Cherastidtham and Mackey (Figure 1.1, 2019).

10 Deming and Noray (2020) demonstrate this effect in the United States, showing that skill obsolescence

lowers the income returns to work experience in faster-changing occupations.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 10

Chart 3.2 Share of employees by skill

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Longitudinal Labour Force Survey.

Note: Occupation is ANZSCO submajor, and skill level as defined in Appendix B. Data are pooled across 2016–2023.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 11

Many people (re)enter the labour market in lower-skilled jobs

Skill level mismatch also means that low-skill job seekers have to compete with high and middle-skill

job seekers for the same roles. Chart 3.3 on the following page shows the next quarter destination

occupations for unemployed people without prior occupation information. This group contains young

job seekers, about half of whom are entering the workforce for the first time. It also includes those

who have been without an occupation for an extended period – such as those coming from periods

of leave or long-term unemployment.

Low-skill workforce entrants are most likely to find employment in Sales Assistant (20 per cent) and

Sales Support (6 per cent) roles; in Hospitality (12 per cent) and Food Preparation (10 per cent) roles;

and as Cleaners (6 per cent), Drivers (5 per cent) and Other Labourers (5 per cent).

Middle-skill workforce entrants have access to a broader range of jobs, especially as Carer and Aides

(13 per cent) and trades, such as Construction (5 per cent) and Automotive Engineers (5 per cent).

However, middle-skilled workforce entrants also find work in lower-skilled occupations. For example,

6 per cent enter Sales Assistant roles, an occupation that typically does not require a qualification.

High-skill workforce entrants are more concentrated among education, health, and business

professional roles. About a third of high-skill workforce entrants find work in lower-skilled

occupations. These patterns follow the over education patterns (Chart 2.2), with lower-skilled health

and administrative jobs being common.

Workers switch jobs across skill levels but within clusters

As with new entrants to the labour market, workers who switch jobs compete with unemployed

people for vacancies. Much of this job switching is within the same occupation. There is some

movement from one skill level to another when people switch occupations. Workers and job seekers

have preferences, foundational skills, and specialised skills required for occupations that shape the

roles they look for in the labour market.

Preferences for the type of work a person wants to pursue develop over time and are affected by

factors including socio-economic status, occupational segregation (such as by sex), and

macroeconomic conditions during childhood.

11

Foundational skills developed through education and workplace experience – such as

communication, teamwork and problem solving – are common across a range of occupations and can

allow workers to switch occupations.

12

11 For example, these preferences are affected by: socio-economic status during childhood, Gore (2015); by

macroeconomic conditions when growing up, Cotofan, Cassar, Dur & Meier (2023); and by gender

stereotypes and highly segregated occupations, Women’s Budget Statement (pp 28–30, 2023).

12 The importance of these foundational skills in a changing labour market is outlined by the National Skills

Commission (pp 146–151, 2021). An examination of the growing importance of – and returns to – social

skills in the labour market is explored in Deming (2017).

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 12

Chart 3.3 Unemployment to employment transition rates for people with no prior

occupation

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Longitudinal Labour Force Survey.

Note: Occupation is ANZSCO Submajor, and skill level group is defined in Appendix A. Data are pooled across 2016 to

2023.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 13

Specialised skills can be specific to a particular job, occupation or industry. These skills tend to be

developed over long periods – through education, training and work experience – and tend to be less

transferable than foundational skills. For example, a school teacher is unlikely to have the skills to

take up a job as a registered nurse, despite the same education level and similar foundational skill

requirements. However, some occupations overlap in specialised skills.

13

While numerical clerks,

business professionals and chief executives are distinctly different occupations, they all require

numerical skills.

Preferences, foundational and specialised skills interact to form clusters of occupational transitions in

the labour market. These clusters can be explored using a transition matrix of job changes. Case

studies are presented in Chart 3.4 to illustrate the patterns of within/between occupation transitions.

• Of business professionals who begin with a new employer, about a third move into specialised

management roles, while 15 per cent remain as business professionals. There is some transition

within the professional environment, particularly into design IT and education. A smaller share

move to lower-skilled occupations that require skills developed in business, such as numerical

clerks and office administrators.

• Of health professionals who begin with a new employer, almost 40 per cent stay within the health

professional occupation. For those who move, the most common destination is to specialist

management. There is also some down-skilling, with moves most likely to health and welfare

support, and carer occupations.

• Automotive engineers are the most likely to stay within their occupation of these case studies,

with about half remaining as automotive engineers after a move to a new employer.

• Carers and aides also have relatively high within-occupation retainment. New occupations tend to

be to health and support workers, or to higher skilled occupations as education or health

professionals.

• Construction and mining labourers tend to move to other manual occupations, with about

two-thirds moving to similar labourer jobs, such as factory or forestry workers, or to machine

operators and driver occupations. About 20 per cent move to trades occupations that tend to

require qualifications, particularly construction trades.

Between-skill mismatch means that significant shares of high- and middle-skill workers are in

occupations that may not make best use of their skills. While most entrants to the workforce find

work aligned with their skill levels, many high- and middle-skilled job seekers find work in lower-

skilled occupations. Geographic mismatch – job opportunities and job seekers being in different

regions – can play a significant role in the efficient working of the labour market. This is explored in

the next section.

13 The similarity of occupations by specialised skills are explored in the Jobs and Skills Australia Australian

Skills Classification (2023).

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 14

Chart 3.4 Select occupation-to-occupation transitions

Destination occupations (rows) as a share of newly employed original occupations

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, ABS Job Vacancies, JSA Internet Vacancy Index.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 15

4 Regional variations in labour market tightness and

matching by skill level

4.1 Exploring labour markets by skill and region

Australia is not a single homogenous labour market. Many factors drive local labour demand and

supply within regions. This means labour market conditions can vary significantly. Cyclical and

structural forces can have different effects on labour demand in regions based on their industrial

composition. Labour supply can respond differently based on its skills mix and demography.

Australia is a large country and geographic mismatch – job opportunities and job seekers being in

different regions – can play a significant role in the efficient working of the labour market. As the

majority of work is done in person, strong demand for labour in one corner of the country is unlikely

to materially reduce unemployment in another corner. Geographic mobility can provide some

solutions to this mismatch. However, this is not a viable option for all jobs or for all job seekers.

The analysis in this section examines the supply of and demand for skilled labour in each region in

Australia. It identifies overall regional trends in tightness and mismatch by skill level, before

examining a series of regional labour markets with distinctly different outcomes.

Geographic mobility is a partial solution to geographic mismatch

Geographic mismatch occurs when there are job seekers and appropriate job vacancies in different

regional labour markets. Geographic mobility – workers coming to jobs, jobs coming to workers, or a

mix of the two – is one tool to reduce geographic mismatch.

• Workers permanently moving to jobs: young people are more likely to move.

14

There is also a

higher propensity for geographic mobility among renters, unemployed and underemployed

people.

15

However, people are most likely to move within the same labour market because of

housing or family reasons rather than work. People who are more established in an area – such as

those with children and those who own their own home – are less likely to move. Long-term

unemployed also face additional challenges in moving long distances in search of work.

16

• Workers moving to jobs via long distance commuting: for employers and employees who cannot

or will not permanently move location, fly-in fly-out (FIFO) and drive-in drive-out (DIDO) provides

an alternative pathway for managing geographical mismatch. This approach has been a defining

characteristic of Australia’s mining booms with significant population shares of mining regions

appearing to be FIFO workers.

17

Long distance commuting is also playing a role in hybrid

arrangements with remote work.

14 Administrative data published by the ABS (2023).

15 Whelan and Parkinson (2017); Productivity Commission (Chapter 7, 2014).

16 Productivity Commission (Chapter 7, 2014). The Productivity Commission also noted that ‘longer distance

moves for the purpose of finding work are likely to be challenging for many long-term unemployed people

due to lower levels of education and skills, poorer health, less access to affordable transport and greater

reliance on family networks for support’ (p 147).

17 D’Arcy, Gustafsson, Lewis and Wiltshire (2012).

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 16

• Jobs moving to workers via remote work: remote work is an option in some jobs. This allows

workers and jobs in different regions to be matched.

The region-skill Beveridge Curve

This analysis splits the labour market into 37 regions and 3 skill groups (used in Section 3) to explore

111 region-skill labour markets in Australia between 2016 and 2022 (see Appendix D).

These regions are used to allow the use of JSA Internet Vacancy Index data by region and can provide

an overview of regional labour market characteristics. However, some regions span particularly large

areas, meaning that some geographic mismatch remains even when looking at specific regions.

All quarterly observations for the region-skill labour market cells are presented in Chart 4.1. It shows

that the high-skill group has persistently lower rates of unemployment for a given vacancy level than

middle or low-skill groups. Across regions, low-skill groups tend to have higher unemployment and

vacancy rates.

Low and middle-skill groups tend to be below the ‘ ’ line (where vacancies equal

unemployment). However, there are some outliers that sit above that line, with greater vacancies

than unemployed within or across skill groups. These areas tend to be in smaller capital cities.

Chart 4.1 Beveridge curve by skill and geography, 2016–2022

Each point represents a quarterly observation of a skill group in a labour region. Log scales.

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, ABS Job Vacancies, JSA Internet Vacancy Index.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 17

4.2 Different labour market conditions across regions

The methodology developed across this, and the previous sections, allows us to measure labour

market conditions over time for individual labour markets (within skills and within regions).

The analysis shows that a broad range of labour market conditions exist within Australia at any point.

Case studies are presented in the figures below to illustrate these structural and temporary

differences. The following figures show unemployment rates and vacancy rates for each region-skill

labour market.

Sydney: Similar trends to national average

The Sydney labour market tends to have higher demand and similar unemployment levels to the

national average. The overall vacancy rate (Panel A) was relatively flat between 2016 and 2019,

before dropping quickly in 2020 and rebounding to surpass previous levels (Chart 4.2). The

unemployment rate has moved broadly inversely to the vacancy rate.

The high-skill labour market (Panel B) tends to be tighter than the middle and low-skill labour

markets. The middle-skill labour market (Panel C) is persistently looser than the high-skill group, with

higher unemployment and lower labour demand. However, the middle-skill Sydney labour market has

tightened significantly over the past 2 years, in line with the national labour market.

The low-skill labour market (Panel D) has higher rates of unemployment and higher rates of

vacancies. Low-skill labour demand in Sydney grew rapidly since mid-2020. Unemployment rates

followed, starting to decline from early 2021 and by 2023 were below pre-pandemic levels and rising

vacancy rates. But within-skill level mismatch remains high, with about 8 per cent of the labour force

unable to be matched to available jobs.

Chart 4.2 Sydney unemployment and vacancy shares by skill group

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, ABS Job Vacancies, JSA Internet Vacancy Index.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 18

Darwin: Persistent within-skill labour shortages

Darwin has had a tighter labour market than the national average, with about the same number of

unemployed job seekers and job vacancies between 2016 and 2019 (Chart 4.3).

During this time, there was an excess of high-skill labour demand and an excess of low-skill labour

supply. From 2022, the Darwin labour market has had a significant excess of labour demand.

This trend has been seen across all skill levels.

While unemployment rates in Darwin are similar to national levels, vacancy rates are elevated across

all skill groups. This indicates that more jobs and job seekers coexist in the same region within the

same skill level, but face higher levels of within-skill mismatch. Darwin has had a persistent shortage

of workers in across the 3 skill groups since 2021.

Chart 4.3 Darwin unemployment and vacancy shares by skill group

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, ABS Job Vacancies, JSA Internet Vacancy Index.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 19

Toowoomba and South West Queensland: Persistent loose labour market

Toowoomba and South West Queensland (Chart 4.4) had a persistently loose labour market between

2016–2023.

While unemployment tends to be lower for high-skilled groups, unemployment remains higher across

all skill groups than the national average. People in the low-skill labour market have experienced

particularly high rates of unemployment.

This is at least in part reflected in low levels of labour demand, with vacancies below national levels

across skill groups, especially for low-skill occupations.

Chart 4.4 Toowoomba and South West Qld unemployment and vacancy shares by skill

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, ABS Job Vacancies, JSA Internet Vacancy Index.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 20

Far North Queensland: Long-run tightening labour market

Far North Queensland (Chart 4.5) has an increasingly tight labour market with average levels of

matching efficiency. Unemployment decreased from 2016–2022 across skill groups. Overall, the

unemployment rate has declined from about double the national rate to the national rate in 6 years.

The unemployment rates of low-skill workers were above 18 per cent in 2016 and have progressively

decreased to below 8 per cent by the end of 2022. The reduction in unemployment has been allowed

by rising demand for labour over this period across all skill levels.

Chart 4.5 Far North Queensland unemployment and vacancy shares by skill group

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, ABS Job Vacancies, JSA Internet Vacancy Index.

4.3 Summary

Australia is made up of heterogenous labour markets, each of which can have different levels of

mismatch and labour market tightness. Some regions experience acute labour or skills shortages at

the same time others have persistently high rates of unemployment. However, much of Australia’s

labour market mismatch is within region and skill groups. In many regions, including in most major

cities, labour supply and demand is currently close to parity. Low-skill regional labour markets in

particular demonstrate high levels of unemployment and high levels of job vacancies, suggesting

within-region, within-skill group matching efficiency needs to improve to further reduce

unemployment.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 21

Appendices

Appendix A Modelling matching efficiency

This paper estimates aggregate matching efficiency following Consolo and de Silva (section 3, 2019).

18

This approach specifies the matching function as a constant returns to scale Cobb-Douglas function of

the vacancy rate and the unemployment rate.

Following their approach, the aggregate matching function is estimated by looking at quarterly job

finding probabilities and labour market tightness (the vacancy-unemployment ratio), with matching

efficiency defined as the time-varying residual from estimating a reduced form matching function.

19

An adjusted version of the Consolo and de Silva (equation 1, 2019) model is:

20

and

(1)

where matching probability

is the share of job searchers the previous period

who found a

job in the current period,

. Labour market tightness,

, is the ratio of job vacancies

and job

searchers,

.

is a control for quarter to account for regular seasonal effects. The residuals,

, can

be interpreted as a measure of matching efficiency in the current period. In what follows, we describe

our implementation of this approach in the Australian setting.

For all models, the period is quarterly and the measure of vacancies in the economy is ABS Job

Vacancies.

21

Different measures of job searchers (and, therefore, matching probability) are explored

in 3 models:

A. Unemployment model: the unemployment model follows a standard Beveridge Curve

framework – and that used in Consolo and de Silva (2019) – by defining job searchers as

unemployed people,

. Unemployment data is sourced from the Labour Force Survey.

22

18 For more detail about how this approach fits into the Beveridge Curve framework, see Consolo and

de Silva (Box 2, 2019); Petrongolo and Pissarides (2001); and Figura and Waller (2022).

19 The authors show that in the European context from 2000, the reduced form matching function approach

reveals similar matching efficiency estimates to an alternative measure derived by estimating the elasticity

between vacancies and unemployment: Consolo and de Silva (equation 2 and chart 5, 2019).

20 A polynomial term

is added to account for potential non-linearity in the relationship between labour

market tightness and job finding probability. The findings in this paper are robust to the removal of this term.

21 ABS Job Vacancies (Australia: Table 1; and states: Table 2). Job vacancy data was not collected between

August 2008 and August 2009 and is linearly interpolated for analysis conducted in this paper.

22 ABS LFS, Table 1. Original series are used. State-based analysis also uses this model, with data coming from

Table 12. Job finding probabilities of unemployed people is sourced from ABS LFS Flows into and out of

employment (GM1).

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 22

B. Non-workers model: expands the definition of job searchers to include NILF job seekers,

. Three groups are considered to be possibly searching for employment within the

NILF cohort: those actively searching for work, those passively searching for work, and those not

searching for work.

23

ABS Longitudinal Labour Force microdata is used to determine how many of

each group enter employment in each period. The number of job searchers in each group is

defined as the number of job finders divided by the hiring rate of the actively looking group.

24

C. Workers and non-workers model: adds employed job searchers to the non-workers model,

including all job searchers in the labour market:

. ABS Longitudinal Labour

Force microdata is used to count the number of new hires from the employed pool, measured

using the share of previously employed workers who have been in their current job for less than

3 months. The share of job searchers who are seeking work at any point is assumed to be fixed at

10 per cent.

23 Treasury research by Parsons and Hickson (2022) [unpublished] shows the ‘not looking for work’ NILF

group is the largest group, accounting for just under half of the whole NILF group. Those who are retired

or permanent unable to work, the second largest NILF group, are excluded. This group has very low levels

of job finding.

24 The intuition is that a NILF person will move from ‘not looking’ or ‘passively looking’ to ‘actively looking’

before finding a job, even if they are only ever measured as being ‘not looking’ in one period and

‘employed’ in the next.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 23

Appendix B Defining skill level groups

This analysis defines skill levels to match vacancies (which have occupations) and unemployed people

(who have education levels and, often, a previous occupation).

Method

In this analysis, skill level is defined as one of 3 exclusive and exhaustive groups:

• High skill: Bachelor’s degree or above required, ABS skill level 1

• Middle skill: Cert III/IV or diploma required, ABS skill level 2 or 3

• Low skill: High school or Cert I/II required, ABS skill level 4 or 5.

A job vacancy’s skill group is defined by the ABS skill level of its ANZSCO occupation. A person’s skill

group is defined by their highest level of education or the skill level of their current or previous job.

• Education level is important to define the skill levels of people without information on their

previous occupation. This group is largely made up of young job seekers, about half of whom are

entering the workforce for the first time. It is also comprised of those who have been without an

occupation for an extended period, such as those coming from periods of leave or long-term

unemployment. Education information has only been collected for each rotation group in the ABS

Longitudinal Labour Force since August 2015.

• Note that as people are classified by the highest education and occupation skill level, this style of

analysis cannot identify ‘under skilled’ workers. By definition a worker without a bachelor’s degree

working in a high-skill occupation that would usually require a bachelor’s degree is classified as

high skill.

Data

• Skill level vacancy shares are taken from the JSA Internet Vacancy Index (by ABS skill level and

state), with state shares scaled to state job vacancy levels from ABS Job Vacancies.

• Skill level employment and unemployment shares are generated from ABS Longitudinal Labour

Force microdata using an individual’s highest level of education and ABS skill level of their current

or previous occupation. ABS skill levels and education levels are then assigned a high, middle or

low-skill grouping according to the method described above.

• Skill level shares are scaled to publicly available employment and unemployment counts from the

ABS Labour Force Survey (original series, not seasonally adjusted).

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 24

Appendix C Occupation transition matrices

ABS Longitudinal Labour Force microdata is used to explore changes in ANZSCO sub-major occupation

for individuals from one quarter to the next. These labour force transition matrices allow us to see

where all people, including unemployed people and those without a previous occupation, tend to

gain employment by occupation when commencing a new job. All transitions observed between 2016

and 2022 are pooled to generate the matrix to avoid sample size issues.

Chart C.1 on the following page shows the full transition matrix.

Treasury Round Up | January 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 25

Chart C.1: Occupation transitions for people commencing new jobs

Source: Treasury analysis of ABS Longitudinal Labour Force Survey.

Note: Pooled quarterly transitions between 2016–2022.

Treasury Round Up | January 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 26

Appendix D Defining region-skill groups

This analysis defines regions and skill levels to match vacancies (which have locations and

occupations) and unemployed people (who have locations, education levels and previous

occupations).

This analysis splits labour market into 37 regions with 3 skill groups (111 cells) to explore varied

conditions. Regions are defined by JSA Internet Vacancy Index (IVI) Regions. Labour force data is

sourced from the ABS Longitudinal Labour Force microdata at Statistical Area 4 (SA4) level before

being corresponded to IVI regions. JSA provides a correspondence tables of SA4 regions to IVI

regions.

These regions are shown in Chart D.1.

Chart D.1: Internet Vacancy Index regions

Source: Jobs and Skills Australia (2023).

Treasury Round Up | January 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 27

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Classifications: Conceptual Basis of ANZSCO.

https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/classifications/anzsco-australian-and-new-zealand-standard-

classification-occupations/2022/conceptual-basis-anzsco#underlying-concepts

Ahn, H. & Crane, L. (2020). Dynamic Beveridge Curve Accounting, Federal Reserve.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/dynamic-beveridge-curve-accounting.htm

Borland, J. (2011). The Australian Labour Market in the 2000s: The Quiet Decade. Reserve Bank of

Australia Annual Conference 2011. https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/confs/2011/pdf/borland.pdf

Consolo, A. & da Silva, A. (2019). The euro area labour market through the lens of the Beveridge

curve. European Central Bank, Economic Bulletin Issue 4/2019.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-

bulletin/articles/2019/html/ecb.ebart201904_01~9070de27a0.en.html

Cotofan, M., Cassar, L., Dur, R., & Meier, S. (2023). Macroeconomic Conditions When Young Shape Job

Preferences for Life. The Review of Economics and Statistics 2023; 105 (2): 467–473.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01057

D’Arcy, P., Gustafsson, L., Lewis, C., & Wiltshire, T. (2012). Labour Market Turnover and Mobility. RBA

Bulletin December Quarter 2012. https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2012/dec/pdf/bu-

1212-1.pdf

Deming, J. (2017). The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market. The Quarterly Journal

of Economics, 132 (4): 1593–1640. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx022

Deming, D., & Noray, K. (2020). Earnings Dynamics, Changing Job Skills, and STEM Careers. The

Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135 (4): 1965–2005. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa021

Deutscher, N. (2019). Job-to-job transitions and the wages of Australian workers. Treasury Working

Paper 2019-07. https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-11/p2019-37418-jobswitching-v2.pdf

Figura, A. & Waller, C. (2022). What does the Beveridge curve tell us about the likelihood of a soft

landing? Federal Reserve. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/what-does-the-

beveridge-curve-tell-us-about-the-likelihood-of-a-soft-landing-20220729.html

Gore, J., Holmes, K., Smith, M. et al. (2015). Socioeconomic status and the career aspirations of

Australian school students: Testing enduring assumptions. Aust. Educ. Res. 42: 155–177.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-015-0172-5

Heath, A. (2020). Skills, Technology and the Future of Work. Reserve Bank of Australia.

https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2020/sp-so-2020-03-16.html

Jobs and Skills Australia. (2022). State of Australia’s Skills: now and into the future.

https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-

02/State%20of%20Australia%27s%20Skills%20Overview.pdf

Jobs and Skills Australia. (2023). Australian Skills Classification.

https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/australian-skills-classification

Norton, A., Cherastidtham, I., & Mackey, W. (2019) Risks and rewards: when is vocational education a

good alternative to higher education?. Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-

content/uploads/2019/08/919-Risks-and-rewards.pdf

Treasury Round Up | January 2024

Labour market matching across skills and regions in Australia | 28

Petrongolo, B., & Pissarides, C. (2001). Looking into the Black Box: A Survey of the Matching Function.

Journal of Economic Literature, 39 (2): 390–431. doi:10.1257/jel.39.2.390

Productivity Commission. (2014). Geographic Labour Mobility. Research Report, Canberra.

https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/labour-mobility/report/labour-mobility.pdf

Richardson, S. (2007) What is a skill shortage?. National Centre for Vocational Education Research

https://www.ncver.edu.au/__data/assets/file/0019/7282/what-is-skill-shortage-4022.pdf

Whelan, S. & Parkinson, S. (2017). Housing tenure, mobility and labour market behaviour: Inquiry into

housing policies, labour force participation and economic growth. AHURI Final Report No. 280,

Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

http://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/280

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Exploring community resilience in Australia | 29

Exploring community resilience in Australia

Prepared by Nicholas Marinucci, Nathan Walsh, Andrew Yung

1

Summary

Resilience is defined as the ability to recover from and adapt to external shocks. In this article,

resilience refers to a broader description of economic and social endurance despite external

shocks, and not just resilience to natural hazards and disaster events.

Resilience empowers individuals, communities, organisations, and systems to thrive in the face

of adversity, adapt to change, and effectively navigate the complexities of our interconnected

world.

Australian regions are ranked by a resilience index which shows significant geographical

variation across the country. Communities in closer proximity to major cities and regional

centres have a higher level of resilience compared to more remote communities.

Findings from the index demonstrate how resilience varies geographically and what factors are

causing these variations. This can help direct efforts and resources towards areas with less

resilience and more vulnerability to negative impacts from external shocks.

1 The authors would like to thank Rebecca Cassells, Simon Ricketts, Paul Cotterill, Nathan Deutscher,

Simon Nash, and Emma Richardson for their valuable comments in reviewing this paper. The views

expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Treasury or the

Australian Government.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Exploring community resilience in Australia | 30

1 Defining resilience

This article introduces the concept of resilience, explains the benefits of communities and

policymakers understanding resilience, and presents insights from quantitative analysis of resilience

across Australia’s regions.

Resilience is a pivotal factor for communities. It bolsters long-term wellbeing, regardless of external

hazards and risks. Resilience is broadly defined as a community’s ability to recover from and adapt to

external shocks while maintaining its structure and functionality.

The definition of resilience can encompass a spectrum of acute or chronic external shocks. It can be

tailored to a more specific scope, aligning with distinct events. For example, labour market resilience

may refer to the ability to maintain a level of employment and real wages despite adverse shocks

such as the closure of a firm with a large market share (Diodato and Weterings, 2015; Grabner, 2021).

In the context of climate change, resilience refers to the ‘capacity of interconnected social, economic

and ecological systems to cope with a hazardous event, trend, or disturbance, responding or

reorganising in ways that maintain their essential function, identity and structure’ (IPCC, 2022).

Resilience is also a term often used in relation to natural hazards and disaster events, describing how

well a community can manage disaster risk through adaptation and recovery processes. It should be

noted that resilience in this article refers to a broader description of economic and social endurance

despite external shocks, and not just resilience to natural hazards and disaster events.

Resilience is complex. It often comprises unobservable attributes that contribute to its advancement

or impede its progress. Nevertheless, understanding resilience and its driving factors can help

promote policy that safeguards the sustainability of vulnerable communities.

Governments have an important role in assisting communities to understand resilience.

A quantitative assessment of resilience can help state and federal governments direct support where

it is needed. Understanding levels of resilience in different regions can help governments and

not-for-profit organisations prioritise support for areas with less resilience. Policymakers can use

insights into underlying factors that foster or hinder resilience to design well-targeted programs

relevant to a community’s specific circumstances. Local councils and active community groups can

benefit from a deeper understanding of resilience and the adaptive capacities of their regions and

surrounds.

Section 2 of this paper discusses the value of resilience investment as opposed to recovery

expenditure. Section 3 highlights the frameworks used to examine resilience, including the

community capitals framework. Section 4 presents empirical analysis of resilience in Australian

regions. Section 5 provides concluding remarks on the role of resilience.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Exploring community resilience in Australia | 31

2 Conceptualising the value of resilience

The value of resilience is the costs avoided by a community when an external shock is realised.

Resilience is closely related to recovery. Resilience and recovery can reduce the consequences of an

event on a community. Resilience can also limit the direct impacts of the event. Recovery can only

reduce the consequences of an event as it occurs once the event is realised. Investing in resilience

can be a cost-effective way for communities to reduce the impacts of external shocks such as financial

crises and natural disasters.

The Resilience Loss Recovery Curve (White et al., 2015) illustrates the different pathways of

community functional capacity before and after an acute disturbance for varying levels of resilience

(Figure 2.1). The red line represents a less resilient community where a shock causes greater social

and economic loss. This is shown in Figure 2.1 as the area between the black line and red line.

Depending on the community’s level of resilience, they may reach an equivalent functional capacity

as prior to the disturbance (‘B’) or they may be left worse off (‘C’). The blue line represents a more

resilient community where a shock causes less social and economic loss. This is shown by the smaller

area between the black line and the blue line. A more resilient community may reach a higher level of

functional capacity in the long run compared to before the acute disturbance occurred (‘A’).

Figure 2.1 Resilience Loss Recovery Curve

Source: White et al. (2015). Adapted from model developed by Hynes, Ross, and Community and Regional Resilience

Institute (2008) and presented at the United States Department of Homeland Security University Summit,

Washington, DC (Community and Regional Resilience Institute, 2008)

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Exploring community resilience in Australia | 32

3 Resilience frameworks

The complexities of community development and resilience have been extensively explored through

various models and frameworks, often crafted by academics, non-government organisations, and

development agencies.

Earlier related research predominantly from the United States includes McKnight and Kretzmann

(1996) who introduced the asset-based community development framework. This framework posits

that efforts to strengthen communities should focus on harnessing the capacities, skills, and assets of

the community’s residents rather than using a deficit-based approach.

Community resilience is presented as an ongoing process by Norris et al. (2008), rather than a static

outcome. Their perspective highlights the importance of linking adaptive capacities for successful

adaptation after an adverse event. They identify economic development, social capital, information

and communication, and community competence as key adaptive capacities contributing to

community resilience.

Building upon the work of Norris et al. (2008), Sherrieb et al. (2010) estimate adaptive capacities

related to economic development and social capital for 82 counties in Mississippi, United States,

using pre-2005 population-level data. Like Norris et al. (2008), Simmie and Martin (2010) describe

resilience as a sequential process that evolves over time. The authors develop an adaptive cycle

model of regional economic resilience, suggesting that adaptation in regional economies follows a

four-phase cycle consisting of reorganisation, conservation, exploitation and release. Each phase is

related to different degrees of resilience, connectedness, and capital accumulation or loss.

Given the extensive literature on models for resilience, Serfilippi and Ramnath (2018) provide a

review of resilience measurement techniques and conceptual frameworks. They categorise resilience

frameworks into 3 groups: descriptive, causal and analytical. Descriptive frameworks focus on

identifying key determinants without delving into causal relations and temporal factors. Causal

models of resilience trace sequences of events, revealing the causal links between shocks, resilience

capacities and outcomes. Analytical models build on causal models by addressing measurement

complexities like aggregation, correlation and endogeneity biases.

Numerous other studies contribute to the discourse on resilience frameworks in communities and

regional economies. Notable among these are works by Magis (2010), Martin (2012), Martin and

Sunley (2015), and Rose (2004).

3.1 Community Capital Framework

Emory and Flora’s (2006) community capitals framework provides another perspective to better

understand resilience. As the community capitals framework underpins the quantitative analysis of

resilience in Australia presented in Section 4, it is useful to explore this framework further.

This descriptive framework proposes that the resources available to a community can be measured

by 7 dimensions (community capitals). These are social, political, human, financial, cultural, natural,

and built capital. A community’s development in each of these dimensions may indicate its overall

living conditions and prosperity. Similarly, these community capitals can be viewed as the core

foundations of resilience. The 7 community capitals are outlined below.

Treasury Round Up | March 2024

Exploring community resilience in Australia | 33

Social

Social capital is the interconnectedness of a community and the propensity for people to have

positive interactions with one another. It also relates to people’s level of involvement in the

community. Aldrich and Meyer (2014) highlight the importance of social capital in recovering from

and adapting to disasters, emphasising that increasing community resilience should primarily involve

strengthening social infrastructure rather than physical infrastructure. Social capital is also a central

component within climate change research and adaptive capacity (Pelling and High, 2005). Social

capital can be measured using observational information such as the number of people who actively

volunteer. Measures of subjective wellbeing such as those reported in the Household Income and

Labour Dynamics of Australia (HILDA) Survey can also be used to assess levels of social capital.

26

Stone (2001) offers a literature review of social capital measurement and categorises measurements

into either structure (networks such as families) or quality (norms such as civic/institutional trust) of

social relations.

Political

Resilience is dependent on political capital because a community’s level of political capital

determines the degree to which a community can act collectively and decisively during a crisis.

Political capital can be reflected through the effectiveness of policy, the frequency of elections, and

public trust in political systems. Aigner et al. (2001) demonstrate the importance of political capital by

showing that empowering low income people through the election mechanism has a positive effect

on both inclusion and citizen participation. For example, indicators like government satisfaction, as

reported in Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research’s Taking the Pulse of the

Nation survey (Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research, n.d.), can act as a proxy

for political capital.

Human

Human capital describes the capabilities of people developed through their education and

experiences. It is critical for the success of a community as it strongly relates to other important

economic factors such as productivity and innovation. Human capital plays a central role in economic

growth (Galor and Tsiddon, 1997; Mincer, 1984; Pelinescu, 2015) and other broader macroeconomic

outcomes. Resilience and human capital are positively related because higher levels of human capital

imply a community is in a better position to draw from its own wealth of knowledge and abilities

when planning for external shocks. Human capital can be measured in a variety of ways such as the

average level of educational attainment, average student test scores, or average amount of work

experience in the labour force.

Financial

Financial capital refers to the community’s means to save and invest to support entrepreneurialism

and wealth accumulation. This is dictated by many factors such as the financial institutions in place,

the amount of opportunity to invest in safe and profitable assets, and how broader national and

international economic conditions are affecting the local economy (for example, through the terms of

26 The HILDA Survey is a household-based panel study that provides data about economic and social