Changes in Airline Service Differ

Significantly for Smaller Communities,

but Limited Data on Ancillary Fees

Hinders Further Analysis

Report No. EC2020036

May 27, 2020

Changes in Airline Service Differ Significantly for Smaller

Communities, but Limited Data on Ancillary Fees

Hinders

Further Analysis

Self

-initiated

Office of the Secretary

| EC2020036 | May 27, 2020

What We Looked At

In 2013 and 2014, reports from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology (MIT) documented a disproportionate decline in commercial air service to

smaller communities. Since that time, there have been concerns that small- and medium-sized

communities continue to have limited access to the National Airspace System. The lack of a recent

analysis, as well as major changes in the industry, prompted our office to update the GAO and MIT

reports. Accordingly, our objective for this self-initiated audit was to detail recent trends in the

aviation industry, particularly as they relate to small- and medium-sized communities.

What We Found

Compared to larger metropolitan areas, smaller communities have experienced disparate effects from

several recent aviation industry trends. For example, departures declined in larger communities by

roughly 12 percent and in smaller communities by about 34 percent. Connectivity—the ability to

connect to and move throughout the national air system—declined by 16 percent in smaller

communities, double the rate in larger communities; however, data limitations hindered our analysis

of delays and cancellations. Similarly, competitive conditions improved in larger communities, but

grew worse in smaller communities, where the cost to fly was also greater. Finally, we found that some

airlines have dramatically increased their revenues from booking charges and other ancillary fees.

However, the Department of Transportation (DOT) does not collect adequate data on ancillary fees,

which reduces its ability to fully assess competition in the industry. Also, ancillary fees are not subject

to the excise tax that funds the Airport and Airway Trust Fund (AATF). We conservatively estimate that

certain carriers’ use of booking fees as a revenue source reduced AATF revenues by $60.6 million in

2019 alone.

Our Recommendations

We made three recommendations to address DOT’s data shortcomings and improve departmental

clarity on the impact of ancillary fees on AATF receipts. The Department concurred with one of our

three recommendations.

All OIG audit reports are available on our website at www.oig.dot.gov.

For inquiries about this report, please contact our Office of Government and Public Affairs at (202) 366-8751.

EC2020036

Contents

Memorandum 1

Result

s in Brief 3

Backgr

ound 4

Depart

ures Decreased Substantially System-Wide but Smaller

Communities Experienced the Greatest Percent Losses 8

Pass

enger Numbers Have Grown Through Increases in Seats and Load

Factors, Despite Departure Declines 13

Smalle

r Communities Lost the Most Connectivity to the National Airspace

System and Data Availability Limits Analysis of Delays and

Cancellations 18

Compet

itive Conditions Improved in Larger Communities but Worsened

in Smaller Communities 23

Flying From Smaller Communities Became Relatively More Expensive, but

Lack of Data on Growing Fees Hinders Analysis 34

Conc

lusion 45

Recom

mendations 45

Agency Comments and OIG Response 46

Acti

ons Required 48

Exhi

bit A. Scope and Methodology 49

Exhi

bit B. Organizations Visited or Contacted 65

Exhib

it C. List of Acronyms 66

Exhib

it D. Major Contributors to This Report 67

Exhi

bit E. Categorization of Select Airlines 68

Exhibit F. List of Multi-Airport PSAs 70

Appe

ndix. Agency Comments 72

EC2020036 1

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Memorandum

Date: May 27, 2020

Subject: ACTION: Changes in Airline Service Differ Significantly for Smaller Communities,

but Limited Data on Ancillary Fees Hinders Further Analysis |

Report No. EC2020036

From:

Charles A. Ward

Assistant Inspector General for Audit Operations and Special Reviews

To: Assistant Secretary for Aviation and International Affairs

Director of the Bureau of Transportation Statistics

A community’s ability to develop economically is impacted by its connections

with other communities and ability to transport people quickly and regularly. In

2013 and 2014, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) International Center for Air

Transportation (ICAT) released a series of reports documenting a

disproportionate decline in commercial air service to smaller communities—

relative to large communities—between 2007 and 2013.

1

When accounting for

service changes affecting smaller communities, GAO and MIT researchers cited

higher fuel costs, reduced demand, demographic changes, industry

consolidation, and capacity discipline.

2

The GAO a

nd MIT reports predated a decline in jet fuel prices

3

in late 2014 and

may not have included the full impact of recent airline mergers. For example, the

final judgment in the merger between US Airways Group, Inc. and AMR

Corporation was issued by the Department of Justice (DOJ) in April 2014, the

firms did not integrate their reservation systems until October 2015. However, the

GAO and MIT analyses only used data through 2013.

1

For example, GAO, Status of Air Service to Small Communities and the Federal Programs Involved (GAO-14-454T),

April 2014 and MIT ICAT, Trends and Market Forces Shaping Small Community Air Service in the United States (ICAT-

2013-02), May 2013.

2

The losses airlines incurred in the late 2000s—in part due to the economic recession and historically high jet fuel

prices—contributed to changes in airlines’ business models. In an effort to cut costs, airlines transitioned to a

capacity-discipline strategy. This strategy reduced seating capacity by offering fewer flights, while reducing the share

of unfilled seats on flights.

3

The per-gallon price fell from $2.73 in September 2014 to $1.50 in January 2015.

EC2020036 2

Despite the airline industry’s profitability since these reports were issued, there

were concerns that many communities’ ability to access the National Airspace

System has not subsequently improved. In particular, these concerns have

focused on airline service to small- and medium-sized communities. For example,

the potential economic impact of this decline in air service received congressional

attention, and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Reauthorization of 2016

authorized the Secretary of the Department of Transportation (DOT) to establish

a Working Group on Improving Air Service to Small Communities.

The lack of recent analysis, airlines’ financial recovery during the past few years,

and the completion of major airline mergers have prompted our office to update

the earlier GAO and MIT analyses to better inform the ongoing policy debate

regarding service to smaller communities. Accordingly, our objective for this self-

initiated audit was to detail recent aviation industry trends, particularly as they

relate to service to small- and medium-sized communities.

4

Specifically, we detail

trends in airline service levels; numbers of passengers flown; airline service

quality, including connectivity; airline competition; and prices paid by airline

passengers for airfare and ancillary services—particularly as they relate to small-

and medium-sized communities.

To meet the objective, we analyzed U.S. Census Bureau (Census) and DOT

datasets that highlighted changes in activity, competition, prices, and service

quality from 2005 through 2017.

5

Because we found that some fees—which are

not included in the base ticket price—have grown considerably, we compiled

information on certain fees through November 2019 in order to account for this

trend. We reviewed airline industry research conducted by Government agencies,

academic economists, and transportation researchers, with a focus on articles

that analyzed competitive practices and service to smaller communities. To better

understand the industry’s considerations in serving smaller communities, we

interviewed representatives from Airlines for America, the Regional Airline

Association, and the Air Line Pilots Association. We also contacted GAO to

discuss their previous research on ancillary fees. We conducted this performance

audit in accordance with generally accepted Government auditing standards.

We appreciate the courtesies and cooperation of DOT representatives during this

audit. If you have any questions concerning this report, please call me at

(202) 366-1249 or Betty Krier, Chief Economist, at (202) 366-1422.

cc: The Secretary

DOT Audit Liaison, M-1

FAA Audit Liaison, AAE-100

4

We included a second audit objective when we announced this review. In a subsequent review, we will provide a

descriptive analysis of factors associated with changes in airline service to small- and medium-sized communities.

5

We started with 2005 so that our baseline would be unaffected by the recession that began in 2008. Our analyses of

ticket prices and competition used data beginning in 2006.

EC2020036 3

Results in Brief

In comparison to larger metropolitan areas, smaller

communities have experienced disparate effects of several

recent aviation industry trends.

• Departures decreased substantially system-wide

6

but smaller communities

experienced the greatest percentage losses. While departures declined in

larger communities by roughly 12 percent, departures dropped about

34 percent in smaller communities. Further, small communities without

Essential Air Service (EAS)

7

saw an even larger decline.

• Passenger numbers have increased through growth in seats per flight and

load factors. The number of seats per flight and passenger load factors

had the largest percentage growth in smaller communities, by more than

35 percent and 12 percentage points, respectively. Still, the total number

of seats fell significantly in smaller communities.

• Smaller communities lost the most connectivity to the National Airspace

System, and data limitations hinder analysis of delays and cancellations.

Connectivity—a measure of a passenger’s ability to easily connect to and

move throughout the national air system—declined among smaller

communities by 16 percent, twice as much as the 8 percent decline in

connectivity among larger communities. Differences in cancellations and

delays by community size appear modest, but coverage of smaller

community service quality was limited until 2018.

• Competitive conditions improved in larger communities, but worsened in

smaller communities. While competition increased on routes originating

from larger communities due primarily to non-legacy carriers entering

these routes, it declined for smaller communities. Further, the price

premium associated with flying from a smaller community—compared

with taking similar flights from a large community—has risen in recent

years.

• Ancillary fee revenue has grown significantly, which may degrade the

quality of DOT’s airline revenue and ticket price data and decrease Airport

6

In this report, the term “system-wide” refers to passenger flights between airports in the contiguous United States.

7

EAS is a DOT program that was put into place following the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 to guarantee that small

communities that were served prior to deregulation maintain a minimal level of scheduled air service.

EC2020036 4

and Airway Trust Fund (AATF)

8

receipts. Also, information we gathered

while conducting our audit shows that some airlines’ revenues from

ancillary fees, such as booking fees, have grown dramatically. However,

while DOT collects data on airline revenues and ticket prices, it does not

collect adequate data on ancillary fees. Without this information, DOT and

the traveling public may not know the impact of these fees on the costs

to passengers and airline revenues for air service from smaller–or larger–

communities. This may reduce DOT’s ability to assess competitive

conditions in the industry. Using available information, we determined

that certain carriers’ use of booking fees as a revenue source can be

conservatively estimated to reduce AATF revenues by $60.6 million in

2019 alone.

We are making recommendations to address DOT’s data shortcomings and

improve departmental clarity on the impact of ancillary fees on AATF receipts.

Background

DOT’s Office of Aviation Analysis initiates and supports the development of

DOT’s public policies regarding economic oversight of the airline industry. The

Office of Aviation Analysis analyzes and supports DOT’s decision makers on

major airline issues, including mergers and acquisitions, joint venture agreements

and immunized international alliances between U.S. and foreign carriers, and

airline distribution practices. Additionally, the Office of Aviation Analysis

administers the EAS program and its Competition and Policy Analysis division

monitors changes in the industry, analyzes industry trends – including

assessments of airline fares, and evaluates policy options on a wide range of

issues. DOT’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) publishes data and

statistics on commercial aviation, which includes data on airfares, air carrier

traffic, and airlines’ financial data. This data is used by analysts within and outside

DOT, and in our report we rely heavily on data published by BTS.

In our analysis, we defined communities using Census criteria and DOT

information on EAS subsidies. We also categorized airlines into two primary

groups—mainline and regional—as well as divided mainline and regional carriers

into subgroups. All of our analysis focused exclusively on airline service between

communities in the contiguous United States.

9

The following describes our

8

The AATF was created under the Airport and Airway Revenue Act of 1970 to provide a dedicated source of funding

for the U.S. aviation system, independent of the General Fund.

9

We also restricted our analysis to airports which had at least 2,500 enplanements on scheduled passenger flights in

at least one year between 2005 and 2017. Throughout this report, airport refers to an airport which met this

enplanement threshold.

EC2020036 5

criteria for identifying communities and community size categories, EAS

communities, and airline categories.

Defining Communities and Community Size

Groups

We determined community boundaries using Census statistical area definitions.

Communities were defined as either a county or set of counties. A set of counties

was considered a single community when Census determined that they were

significantly economically and socially integrated, see exhibit A for further details

on our community definitions. This resulted in a number of communities that

contain multiple airports, see exhibit F.

We categorized communities into five size groups—large (L), medium-large (ML),

medium (M), medium-small (MS), small (S)—such that the combined population

of all communities within a size group was approximately 20 percent of the

population of the contiguous United States in 2010. Throughout the report, when

we use the term “smaller” to describe communities, we are referring to both small

and medium-small communities. Also, we use the term “larger” to refer to both

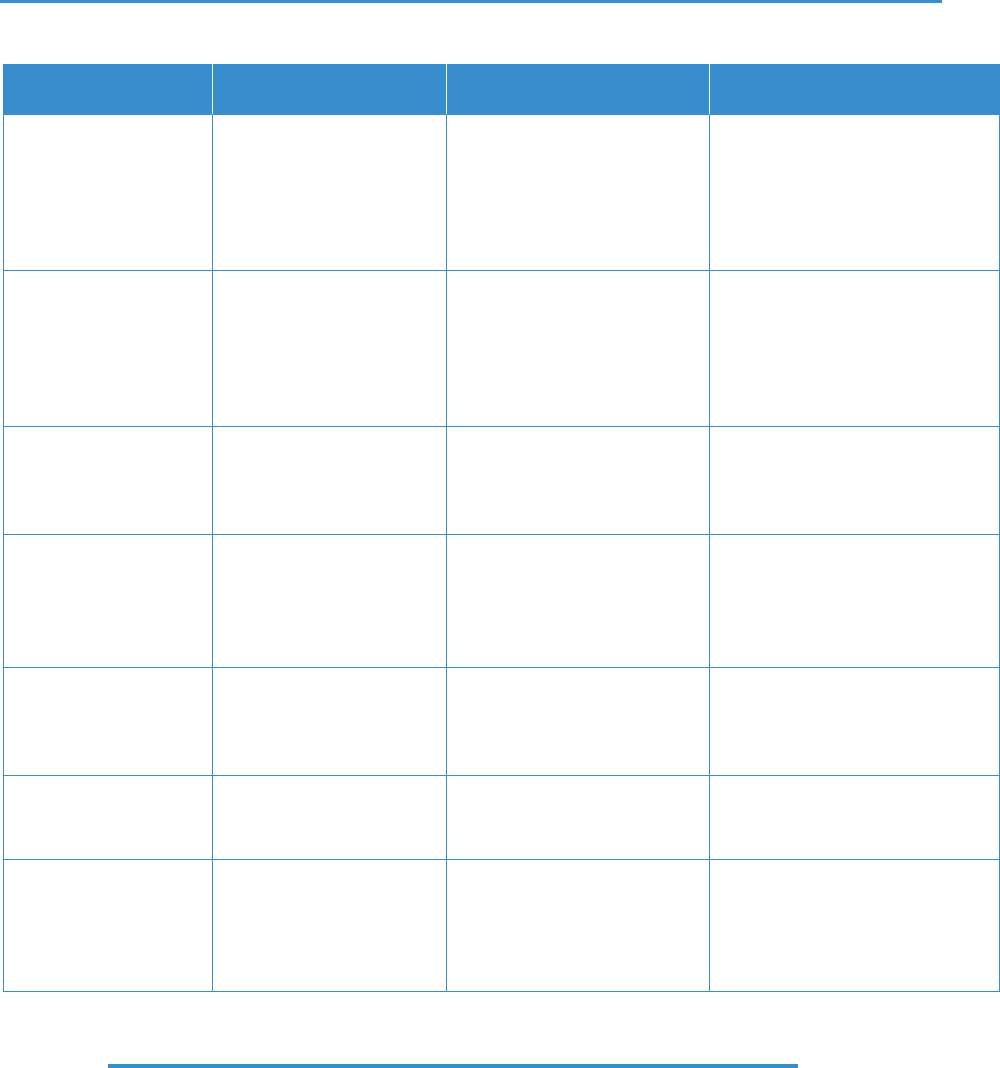

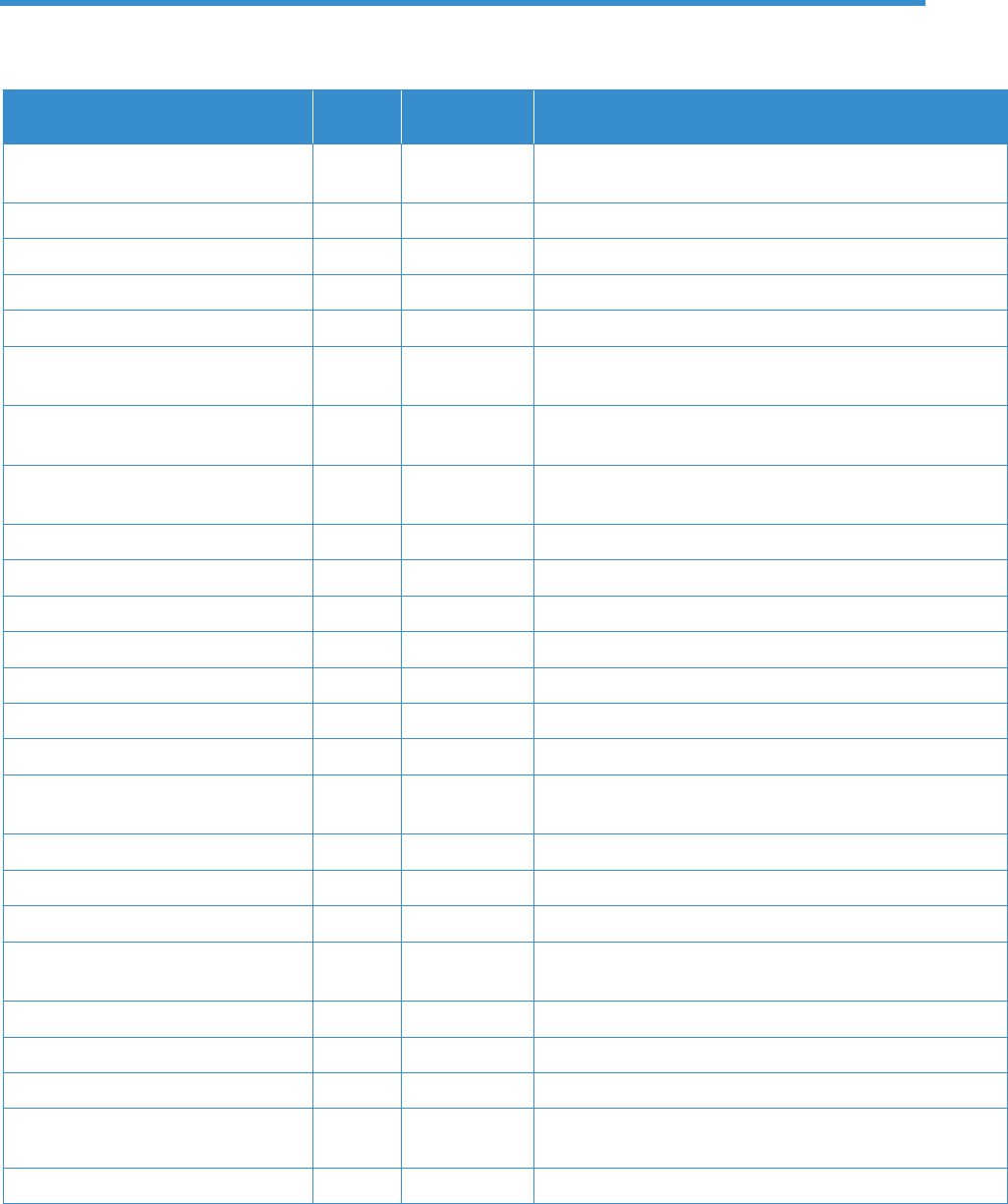

medium-large and large communities. Table 1 below provides information on our

community size categories and their population statistics.

EC2020036 6

Table 1. Community Size Groups

Category

a

Number of

Communities

Total

Population

Percent of

Total U.S.

Population

b

Median Size

Community and

Its Population

c

Population Range

Large 5

68.0

million

22.4

Chicago-

Naperville, IL-IN-

WI;

9.84 million

8.15 million to 23.1 million

Medium-Large 10

57.5

million

19.0

Houston-The

Woodlands, TX;

6.11 million

3.68 million to 7.89 million

Medium 26 59.5

million

19.6 Salt Lake City-

Provo-Orem, UT;

2.27 million

1.46 million to 3.52 million

Medium-Small 83 60.5

million

20.0 Jackson-

Vicksburg-

Brookhaven, MS;

660,368

374,536 to 1.41 million

Small with

commercial

service & no

EAS service

134

20.4

million

6.7

Mesa County,

CO;

146,723

5,172 to 373,802

Small with EAS-

subsidized

commercial

service

102

7.8

million

2.6

Franklin County,

NY;

51,599

7,369 to 279,771

Small, without

commercial

service

1,215 29.6

million

9.7 Winn Parish, LA;

15,313

614 to 331,298

a

Community statistics including EAS community information are for 2010.

b

Total U.S. population is for the contiguous U.S.

c

The median is the middle value and is less sensitive to outliers than an average. There are as many

communities larger than the median size community as there are communities smaller than it. The

median population column reports the higher of the central two communities when there is an

even number of communities.

Source: OIG analysis of Census and DOT data

Essential Air Service

The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 granted airlines the freedom to determine

which routes they serve. This included granting carriers the ability to terminate

airline service to any community without Government approval—raising concerns

EC2020036 7

that communities with relatively low traffic could lose service entirely. To address

these concerns, the EAS program was established to ensure that small

communities retain a link to the National Air Space System. Service at EAS

communities is typically maintained by giving an air carrier a direct subsidy to

provide flights between the EAS community and a medium or large hub airport,

where passengers can connect to the national network.

Throughout this report, we define an EAS community as a small community with

service subsidized under the EAS program in at least one quarter of a given year.

That is, if a small community received an EAS subsidy in at least one quarter of a

particular year, then we consider it to be an EAS community in that year. As of

May 2018, there were 108 active EAS contracts.

10

In 2018, the yearly cost of the

subsidies was $285.8 million, for an average of $2.65 million per EAS contract.

Categorization of Air Carriers

To understand air carriers’ roles in serving smaller communities, we categorized

them into broad groups based on a few components of their operations. At the

highest level, provision of air services is divided between mainline carriers and

regional carriers. A mainline carrier—such as Delta Air Lines or Frontier Airlines—

is often the carrier that sells the ticket for an air travel itinerary, also known as the

marketing carrier.

11

Also, mainline carriers often operate the associated flights,

particularly on long-distance flights and flights using larger aircraft. In other

cases, the mainline carrier markets a flight, while a regional carrier—such as

SkyWest Airlines or Air Wisconsin Airlines—operates the flight under contract

with the mainline carrier.

We further categorized mainline carriers as either legacy or non-legacy carriers.

Legacy carriers operated routes prior to passage of the Airline Deregulation Act

of 1978. Six of these airlines remained in operation in 2005—American Airlines,

Continental Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Northwest Airlines, United Airlines, and US

Airways.

12

Airlines that began operation after deregulation are considered non-

legacy carriers.

10

This figure includes some contracts which were awarded to airports which were not in a small community. EAS

contracts which lie outside a small community are included in the cost figures presented in this paragraph, but

otherwise are not defined as EAS communities in the report.

11

Marketing carriers may sell tickets through direct channels such as the carrier’s webpage, or through third party

distributors, such as online travel agents.

12

Alaska Airlines and Southwest Airlines operated prior to deregulation, but neither had a significant network in the

contiguous United States at that time. Because our analysis focuses on service within the contiguous United States,

we do not define them as legacy carriers for the purposes of this report.

EC2020036 8

We then divided non-legacy carriers into two categories. Low-cost carriers

(LCCs)—such as Southwest and JetBlue—typically achieve lower costs than legacy

carriers. Ultra-low-cost carriers (ULCCs)—such as Allegiant Air and Spirit

Airlines—achieve even lower costs than LCCs. ULCCs are also distinct from LCCs

and legacy carriers in their reliance on ancillary fees for a significantly greater

share of their revenue than the other mainline carriers.

Lastly, we categorized regional carriers based on their ownership status, as some

regional carriers are held by a mainline carrier’s holding company while others

are independently-owned. The latter are referred to in this report as independent

regional carriers. Regional carriers that are held by a mainline carrier’s holding

company are referred to as “non-independent.” Exhibit E lists carriers by category.

Figure 1 below depicts the categorization of airlines used throughout this report.

Figure 1. Categorization of Air Carriers

Source: OIG generated

Departures Decreased Substantially System-Wide

but Smaller Communities Experienced the Greatest

Percent Losses

Departures have fallen in every community size group since 2005 but smaller

communities experienced the greatest percent declines. Reductions in flight

frequencies accounted for most of the system-wide decline but reductions in

nonstop destinations served also contributed substantially. Small non-EAS

communities experienced much larger reductions in both departures and

nonstop destinations than small EAS communities.

EC2020036 9

Smaller Communities on Average Had

the Greatest Percent Reductions in

Departures

From 2005 through 2017, the number of system-wide passenger flights fell by

19.2 percent. However, the percent change in departures varied considerably

across different community size groups. On average, larger communities lost

roughly one-tenth of their departures, medium-sized communities slightly less

than one quarter, and smaller communities approximately one-third. Notably,

excluding EAS communities, the decline in departures from small communities

was even larger, about 40 percent on average. Figure 2 below is a line chart that

depicts the percent changes in departures by community size.

Figure 2. Percent Change in Departures by Community Size

Note: Excludes EAS communities. Baseline is 2005.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

In addition to large average declines across different community size groups,

certain communities experienced significant reductions in departures during this

period. For example, five medium-sized communities—Cincinnati, OH, which saw

a 77.1 percent decline; Pittsburgh, PA; Greensboro, NC; Cleveland, OH; and

Milwaukee, WI—lost over half of their departures, often resulting from an airline

shifting the focus of its network away from an airport after a merger. Despite

such dramatic changes, the median

percent decline in departures—a measure

EC2020036 10

that is not sensitive to outliers—for each community size group was similar to its

total percent decline. Table 2 below shows the median percent change in

departures that occurred for the different community size groups.

Table 2. Median Percent Declines in Departures

Community Size

Group

Median Percent Decline

in Departures

Large 5.9

Medium-Large 18.0

Medium 21.8

Medium-Small 31.3

Small 32.3

Source: OIG analysis

Flight Frequency Reductions Accounted

for Most Departure Declines but

Destination Losses Were Also Sizeable

Reductions in flight frequencies to a destination accounted for 69.7 percent of

declines in departures while reductions in the number of nonstop destinations

13

served accounted for 30.3 percent. Although all community size groups

experienced a decline in flight frequencies, only medium and smaller

communities lost nonstop destinations. Nevertheless, while large communities

saw substantial growth in the number of nonstop destinations served, their total

departures still fell because of substantial losses in flight frequency.

Reductions in flight frequencies accounted for the majority of departure declines

in all except the medium and medium-small communities. Average flight

13

In this section, we focused exclusively on daily nonstop destinations, which we consider to be particularly important

for non-leisure travel. On average, daily destinations accounted for 95.5 percent of departures from small

communities and 99.6 percent of departures from large communities in 2017. We define “daily” destinations as those

that have over 250 flights per year and connect an origin and a destination community. This requires an average of at

least one flight per weekday, while allowing for a small number of cancellations. Note that this definition does not

differentiate between carriers. If Delta offered once-daily service on a route from January to June before exiting the

market, then United entered the market and offered once-daily service on this route from July to December, the route

is coded as a daily route. In addition, this definition includes seasonal routes as long as they accumulate over 250

flights in the year.

EC2020036 11

frequency

14

fell 19.0 percent in large communities, as shown by the decline from

15.3 to 12.4 in the figure below. It fell by 23.5 percent in small communities,

including EAS communities, and by 23.7 percent when EAS communities are

excluded. The comparable figure for medium-large communities showed a

15.7 percent drop. Figure 3 is a bar chart that depicts flight frequencies over time

by community size.

Figure 3. Average Daily Flights on Daily Routes

Note: Daily routes offer at least 250 flights in a given year.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

In contrast to reductions in flight frequencies as shown above, larger

communities experienced increases in total daily destinations served while

smaller and medium-sized communities saw significant declines between 2005

and 2017. Specifically, large communities saw a 12.5 percent average increase in

daily destinations and medium-large communities saw a 3.7 percent average

increase. Medium and medium-small communities had declines in daily

destinations of 17.1 and 21.0 percent on average respectively. Small communities’

daily destinations fell by only 5.7 percent when EAS communities were included,

which is not surprising given that 118 of the 236 small communities were EAS

communities at some point from 2005 through 2017. Figure 4 below is a line

14

Average flight frequency is the unweighted average of flight frequencies across all daily routes within each

community size group.

EC2020036 12

chart that depicts the percent change in daily nonstop destinations by

community size.

Figure 4. Percent Change in Daily Non-Stop Destinations by

Community Size

Note: Excludes EAS communities. Baseline is 2005.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

However, when the sample is restricted to non-EAS communities, small

communities lost service to 20.8 percent of their daily destinations on average.

Concurrently, the proportion of small community service accounted for by EAS

flights has grown from 12.7 to 20.1 percent. Figure 5 is a line chart that depicts

the percent changes in small community flights by whether or not they are

subsidized by the EAS program.

EC2020036 13

Figure 5. Percent Change in Small Community Departures: EAS-

Subsidized vs. Unsubsidized

Note: Baseline is 2005.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

In summary, large and medium-large communities saw an increase in the number

of nonstop daily destinations on average, but a decrease in flight frequency on

average to those destinations. Medium and medium-small communities saw a

large decline in nonstop destinations, but those destinations that remained saw a

modest decline in frequency. Among small communities, the median community

neither gained nor lost destinations when EAS communities are included, but the

median small non-EAS community experienced a significant decline in daily

destinations. Small communities also saw a considerable decline in flight

frequency.

Passenger Numbers Have Grown Through Increases

in Seats and Load Factors, Despite Departure

Declines

Despite departure declines, system-wide passenger numbers grew between 2005

and 2017. Only medium-small communities experienced a decline in passenger

EC2020036 14

numbers. In other community size groups, increases in seats per flight and load

factors were sufficiently large to offset departure declines. Both of these increases

were largest in percent terms in small communities. Still, the total number of

seats fell significantly only in smaller communities.

Passenger Numbers in 2017 Exceeded

2005 Levels for Most Community Size

Groups

From 2005 through 2017, the number of passengers flown by air carriers grew

from 636 million to 711 million—an 11.8 percent increase. Small communities

saw an increase of 9.6 percent in the number of passengers flown, while medium-

small communities were the only community size group with a decline in

passengers between 2005 and 2017. However, even in medium-small

communities, the number of passengers was down by only 2.5 percent overall

and has risen every year since 2013. Figure 6 is a line chart that depicts the

percent change in passengers by community size.

Figure 6. Percent Change in Passengers by Community Size

Note: Baseline is 2005.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

EC2020036 15

The data shows that airlines were able to increase the number of passengers

carried, despite the decline in departures, through increasing the number of

passengers per flight. The greatest growth in the average number of passengers

per flight—62.4 percent—occurred on flights originating in small communities,

which carried an average of 26.6 passengers in 2005 and 43.2 in 2017.

The Number of Seats Per Flight Grew

Substantially but Total Seats Still Fell

Significantly in Smaller Communities

System-wide, seating capacity was 0.8 percent lower in 2017 than it was in 2005.

This is a markedly smaller decline than the nearly 20 percent reduction in flights

during this same period. This was largely a result of airlines’ upgauging since

2005. Upgauging involves the airline changing the aircraft they use to models

with higher seating capacities. Notably, airlines also increased the quantity of

seats within aircraft models during this time. Figure 7 is a bar chart that shows the

growth in seats on several airplane models.

Figure 7. Average Seating Capacity of Select Aircraft

Note: MD-80 includes the MD-81, MD-82, MD-83, and MD-88.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

EC2020036 16

The average seating capacity per flight has increased in all community size

groups. In absolute terms, medium-sized communities saw the greatest increase

in average seating capacity, with the number of seats per flight rising from 96.6 in

2005 to 124.6 in 2017, a 29.0 percent gain. The other four community size groups

all saw similar absolute increases in average seating capacity, but this represented

the highest percent change—35.4 percent—for small communities. Notably,

average seating capacity changes in small communities were even greater when

only considering non-EAS communities—42.7 percent. In comparison, the

percent increases in average seating capacity for large and medium-large

communities were 14.8 percent and 16.2 percent, respectively. Figure 8 is a bar

chart depicting average seats per flight by community size.

Figure 8. Average Seats per Flight by Community Size

Note: Excludes EAS communities.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

However, the marked growth in seats per flight did not fully offset the impact of

departure declines on airline seating capacity in smaller communities. The total

number of seats fell 8.7 percent in small communities, and 14.2 percent in

medium-small communities. In contrast, total seating capacity in large

communities grew 4.8 percent, and fell by just 0.3 percent in medium-large

communities. The minor decline in system-wide seating capacity was the net

result of these different changes in larger and smaller communities. Figure 9 is a

line chart showing changes in total seats by community size.

EC2020036 17

Figure 9. Percent Change in Total Seats by Community Size

Note: Excludes EAS communities. Baseline is 2005.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

Load Factors Increased in All Community

Size Groups

Higher load factors—defined as the ratio of passengers to seats on a plane—

enabled the significant growth in passenger numbers despite the slight decline in

system-wide seating capacity. Apart from small communities, the different

community size groups’ load factors in 2005 were between 69.9 and 73.6 percent,

and grew 8.4 to 9.6 percentage points by 2017. In contrast, small communities

had significantly lower load factors in 2005 than other community size groups,

but experienced the highest load factor growth rate, particularly in non-EAS

communities—12.0 percentage points. Figure 10 is a bar chart that shows that

load factors increased significantly for all five community groups.

EC2020036 18

Figure 10. Load Factor Percent by Community Size

Note: Excludes EAS communities.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

Smaller Communities Lost the Most Connectivity to

the National Airspace System and Data Availability

Limits Analysis of Delays and Cancellations

Connectivity—a measure of a passenger’s ability to easily connect to and move

throughout the National Airspace System—declined across all community size

groups from 2005 to 2017. However, the average decline in connectivity among

smaller communities was twice as big as in larger communities. Data on delays

and cancellations were not reported for a large share of flights in smaller

communities during this time, but the available data showed modest differences

in delays and cancellations across community sizes.

EC2020036 19

Smaller Communities’ Connectivity Has

Declined Twice as Much as Larger

Communities’ Since 2005

Between 2005 and 2017, the average connectivity loss in smaller communities

was about twice as high as in larger communities, 16.3 and 7.8 percent

respectively. Further, every community size group lost connectivity between 2005

and 2017. However, the average decline for the medium-sized communities was

only 1.4 percent. Figure 11 is a line chart that shows the percent change in

average connectivity by community size.

Figure 11. Percent Change in Average Connectivity by Community

Size

Note: Baseline is 2005.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

Our connectivity calculations were based on the Airport Connectivity Quality

Index (ACQI), developed by researchers at MIT’s International Center for Air

Transportation. The ACQI accounts for: the number of nonstop and connecting

destinations, with connecting destinations receiving less weight; the frequency of

available scheduled flights to the nonstop destinations; and the quality of a

destination, as a proxy for economic, social, cultural, and political importance. The

ACQI captures the quality of an airport destination by assigning weights to

EC2020036 20

airports based on their FAA airport hub type designation.

15

This means that a

flight to a large city or a major connecting hub is weighted more heavily than a

flight to a smaller community with limited connecting options. Instead of

calculating the connectivity by airport, we calculated it by community, community

size group, and system-wide, see exhibit A for connectivity calculation details.

Our calculations show that the National Airspace System experienced a large

decline in connectivity from 2007 to 2010. Subsequently, the average connectivity

of smaller communities continued to decline, while the average connectivity from

other communities stabilized or grew. For all but small communities, the average

connectivity score bottomed out in 2014 and subsequently began to increase.

Further, from 2005 through 2017, smaller individual communities were far more

likely than larger individual communities to undergo a significant decline in

connectivity. During this time, nearly half of smaller communities saw their

connectivity decline by more than 20 percent, while fewer than one in seven

larger communities saw their connectivity decline by more than 20 percent.

Differences in Cancellations and On-Time

Performance Across Community Sizes are

Modest, but Data Limitations Hinder

Analysis

We found that passengers flying to smaller communities were just as likely to

have their flights canceled, but less likely to be delayed, as those flying to larger

communities. Also, the average delay of late arriving flights in smaller

communities increased over time to nearly the same level as in the larger

communities by 2017. However, lack of data coverage may limit the

representativeness of these conclusions for smaller communities—as the services

provided by carriers that fell below a revenue threshold were not reported (e.g.,

Allegiant Air and Air Wisconsin Airlines). Specifically, prior to 2018, FAA required

carriers with more than 1.0 percent of total domestic scheduled passenger carrier

revenues to report flight delays and cancellations. Consequently, over the period

of our analysis, the average proportion of flights with service quality data

16

was

only 60.0 percent for smaller communities in comparison to 81.6 percent for

larger communities. Importantly, starting in 2018 FAA reduced this reporting

threshold to 0.5 percent. This change brought the share of flights with service

15

FAA classifies airports’ hub type as Large, Medium, Small, or Nonhub, based on annual passenger enplanements.

16

FAA’s Airline Service Quality Performance database is the primary source for information on airline delays and

cancellations.

EC2020036 21

quality data for 2018 to 92 percent in the smaller communities and to nearly

100 percent in the larger communities.

The available data show that, from 2005–2017, flight cancellation percentages

generally declined and were lowest for passengers flying to medium-sized

communities. While the cancellation percentages for both small and large

communities declined by 2017, both experienced increased cancellation

percentages in 2011. Figure 12 is a bar chart showing cancellation percentages by

community size.

Figure 12. Cancellation Percentage by Community Size

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

On-time performance—the percentage of flights no more than 15 minutes late—

to all communities generally improved by 2017, although large communities

experienced deteriorating performance between 2011 and 2017.

17

Figure 13 is a

bar chart showing on-time performance percentage by community size.

17

Some of the improvement in on-time performance may have resulted from increased schedule padding by airlines.

For more details, see Dennis Zhang, Yuval Salant, and Jan A. Van Mieghem, Where Did the Time Go? On the Increase

in Airline Schedule Padding Over 21 Years (August 24, 2018).

EC2020036 22

Figure 13. On-Time Performance Percentage by Community Size

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

While passengers arriving late to smaller communities experienced shorter delays

than those arriving late to larger communities, that difference narrowed by 2017,

as the length of delays in smaller communities worsened. Lateness—the minutes

of delay for flights that arrived later than 15 minutes after their scheduled arrival

time—for passengers flying into smaller communities was 5 minutes lower than

in larger communities in 2005; by 2017, the difference decreased to 1 minute. The

downward trend was the result of increasing lateness at smaller communities,

from approximately 48 minutes in 2005 to 59 minutes in 2017. Figure 14 below is

a bar chart showing average minutes of delay for delayed flights by community

size.

EC2020036 23

Figure 14. Average Minutes of Delay for Delayed Flights by

Community Size

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

Competitive Conditions Improved in Larger

Communities but Worsened in Smaller

Communities

Domestic airline services consolidated substantially from 2006 to 2017. This

occurred within both the mainline and regional segments. However, since 2006,

different community size groups have experienced diverging outcomes.

Competition increased on routes from larger communities, but declined on

routes from smaller communities. Accounting for part of this difference is that

non-legacy carrier service in larger communities expanded more than in smaller

communities. Lastly, non-legacy carriers differ substantially in their strategies for

serving smaller communities.

EC2020036 24

Both the Mainline and Regional Airline

Industry Segments Underwent

Substantial Consolidation

Mainline carriers and regional carriers divide the provision of commercial airline

services between them, and both industry segments have become substantially

more consolidated.

18

The share of passengers purchasing tickets from the four

largest mainline carriers has risen considerably—from 58 percent in 2006 to

79 percent in 2017. Similar changes occurred in the regional segment during this

time. The four largest regional airline holding companies combined to carry

55 percent of all passengers flying on a regional carrier in 2006. By 2017, this

figure rose to 76 percent. Even greater consolidation occurred among the subset

of regional holding companies that are independent. Specifically, the four largest

independent regional airline holding companies combined to carry 66 percent of

all passengers flying on an independent regional carrier in 2006, and this figure

rose to 94 percent by 2017.

While the passenger share of the four largest firms in each segment illustrates the

scale of consolidation among larger firms, it offers a limited image of how each

segment evolved. The industry has restructured considerably since 2000. Legacy

airlines struggled financially for much of 2000 through 2010, and underwent a

series of major mergers from 2005 through 2013. Of the six legacy airlines

operating in 2005, only three remained in 2017. Also during this period, LCCs

expanded and ULCCs grew dramatically. For example, LCC JetBlue’s passenger

share rose from 3.8 percent in 2006 to 5.4 percent in 2017. The combined

passenger share of ULCCs Allegiant Air, Frontier Airlines, and Spirit Airlines rose

from 3.0 percent in 2006 to 9.5 percent in 2017.

Additionally, non-legacy carriers’ passenger share rose from 35.4 percent in 2006

to 45.9 percent in 2017. The entry of non-legacy carriers into new routes has

been cited by regulatory agencies and researchers as a means to promote

competition—in light of legacy carriers’ consolidation. For example, the DOJ

ruled that US Airways Group and AMR Corporation could merge under the

subsequently formed American Airlines Group. However, they were also required

to offer 26 slots

19

to non-legacy carriers—16 at Reagan National Airport to

JetBlue Airways, Inc. and 10 slots at LaGuardia Airport to Southwest Airlines, Inc.

18

We conducted our analysis of competition of mainline carriers throughout this section using marketing carriers.

Because regional carriers primarily operate flights marketed by mainline carriers, we computed measures of regional

market structure using operating carriers.

19

A slot is an authorization to either take-off or land at a particular airport on a particular day during a specific time

period. In addition to divestitures at Reagan National Airport and LaGuardia Airport, the ruling also required

EC2020036 25

The regional segment also underwent significant restructuring over this

timeframe. We conducted our analysis of regional airlines using airline holding

companies rather than individual airlines in scenarios where multiple airlines were

held by the same company. Regional airline holding companies often own

multiple regional airlines. Some of the increase in regional concentration can be

traced to merging mainline carriers’ subsidiaries falling under the same holding

company after the mainline partners merged. For example, the regional

subsidiaries of US Airways Group and AMR Corporation were each placed under

the newly formed American Airlines Group, Inc. after the two companies merged.

However, changes in the structure of the regional airline industry did not result

entirely from mergers of mainline carrier holding companies. For example, the

independent regional holding company SkyWest, Inc. acquired two large

independent regional airlines—Atlantic Southeast Airlines, Inc. in 2005 and

ExpressJet Airlines, Inc. in 2010. In 2005, SkyWest, Inc. carried 18.2 percent of

passengers flying on independent regional airlines, while ExpressJet carried

13.7 percent of passengers, and Atlantic Southeast carried 8.4 percent of

passengers. By 2012, the SkyWest, Inc. holding company carried 46.8 percent of

passengers flying on independent regional airlines.

To better measure the changes in airline industry concentration, we use the

Hirschmann-Herfindahl Index (HHI). This is a standard measure of industry

concentration used by DOJ and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The HHI is

calculated as the sum of the squared value of the passenger share of each

airline.

20

The HHI ranges from zero to 10,000, and a greater HHI corresponds to a

more concentrated market. DOJ and FTC generally classify markets as

unconcentrated if the HHI falls below 1,500; moderately concentrated if the HHI

lies between 1,500 and 2,500; and highly concentrated if the HHI lies above 2,500.

The maximum value of 10,000 indicates a monopoly.

The changes in the HHI from 2006 through 2017 shown in the figure below

indicate that every industry segment underwent a sizeable degree of

consolidation. The increase was greater among the regional segment (859 points)

and the independent regional segment (1,714 points) than it was among the

mainline segment (550 points). Based on the DOJ and FTC classification, both the

mainline and regional markets were unconcentrated in 2006, but became

moderately concentrated by 2017. The independent regional market was likewise

divestiture of gates at Boston Logan International Airport, Chicago O’Hare International Airport, Dallas Love Field, Los

Angeles International Airport, and Miami International Airport. Research has shown that these divestitures improved

gate access of non-legacy carriers and resulted in lower airfares on routes with forced divestitures. For more details,

see: Zhou Zhang, Federico Ciliberto, and Jonathan Williams, “Effects of Mergers and Divestitures on Airline Fares,”

Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, vol. 2603, no. 1 (2017), pp. 98-104.

20

Letting

represent firm j’s share of all passenger enplanements in a given year, = 10,000

. The index

can alternatively be computed using revenue rather than numbers of passengers.

EC2020036 26

unconcentrated in 2006 and became highly concentrated by 2017. Figure 15 is a

bar chart with the HHI by market segment for 2006, 2011, and 2017.

Figure 15. HHI by Market Segment

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

Regional carriers play a critical role in service to smaller communities, as

passengers in these communities are more likely to be served by the regional

carriers than passengers in larger communities. From 2005 through 2017,

regional carriers flew 75 percent of passengers in small communities and over

40 percent of passengers in medium-small communities, as compared to around

20 percent of passengers in larger communities.

Economists and other researchers have studied the relationship between mainline

competition and outcomes such as prices and service quality, but we are unaware

of any study that examines the possible impacts of regional consolidation. For

example, whether regional consolidation can impact ticket prices by impacting

contract negotiations with their mainline partners is unknown.

21

21

For example, Millou and Petrakis study mergers in the upstream sectors of vertically related industries, focusing on

the relationship between contract types and market structure. Economists have referred to the mainline and regional

airlines as vertically related, with the mainline carriers representing downstream firms and regional carriers

representing upstream firms. For more, see Chrysovalantou Millou and Emmanuel Petrakis, “Upstream horizontal

mergers, vertical contracts, and bargaining,” International Journal of Industrial Organization, vol. 25, no. 5 (2007),

pp. 963–987.

EC2020036 27

Route-Level Competition Increased in

Larger Communities and Declined in

Smaller Communities

Passengers flying from smaller communities had fewer carriers to choose from

when purchasing tickets in 2017 than in 2006. During this time, the average

number of effective competitors

22

—which are holding companies that sold at

least 5 percent of tickets between an origin and destination in the year—for a

passenger flying from a small community fell from 2.66 to 2.51. The average

number of effective competitors for a passenger flying from a medium-small

community fell from 3.73 to 3.33. In contrast, passengers flying from larger

communities had more carriers to choose between in 2017 than in 2006. During

this time, the average number of effective competitors for a passenger flying

from a medium-large community rose from 3.73 to 4.03, while the average

number of effective competitors for a passenger flying from a large community

grew from 4.26 to 4.56.

While useful, the measure of effective competitors does not account for the

relative size of the competitors. The HHI provides more information than the

average number of effective competitors, as it depends on both the number of

competitors and the difference in competitors’ size. Given two markets with the

same number of competitors, the HHI will be lower—indicating stronger

competition—in the market with more similarly-sized competitors. For example,

consider a route that initially has one competitor and consequently, 100

= 10,000.

If a second competitor begins serving this route and captures 10 percent of the

market, the HHI would fall to 90

+ 10

= 8,200. If a second competitor begins

serving this route and captures 40 percent of the market, the HHI would fall to

60

+ 40

= 5,200. Each scenario brings one additional competitor, but the lower

HHI indicates the latter has a greater effect on competition.

We find that the divergence in competitive conditions between smaller and larger

communities is also present when the HHI—rather than effective competitors—is

used to measure competition. The HHI in small and medium-small communities

rose between 2006 and 2017, indicating a decline in competition. In contrast, the

HHI in large and medium-large communities fell during the same period,

22

Effective competitors and the HHI are defined based on the marketing carrier, and weighted by the number of

passengers on the route. We included both direct and indirect itineraries between an origin and destination because

airlines which offer direct flights also compete with airlines offering indirect flights. In 2017, 74.5 percent of

passengers flew direct, 24.5 percent of passengers made one stop, 0.9 percent of passengers made two stops, and

0.1 percent of passengers made at least three stops.

EC2020036 28

indicating an increase in competition. Figure 16 is a bar chart showing route-level

HHI by community size for 2006, 2011, and 2017.

Figure 16. Average Route-Level HHI by Community Size

Note: Average HHI is calculated weighting by the number of passengers on each

route in a given year.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

Expansion of Non-Legacy Carriers Was

Substantial in Larger Communities, but

Modest in Smaller Communities

The divergence in competition on routes serving smaller communities, in

comparison to larger communities, can be partially explained by differences in

the expansion of non-legacy carriers across different community size groups. The

average number of legacy carriers competing on a route fell significantly across

all community size groups from 2006 to 2017. At the same time, non-legacy

carriers substantially expanded their presence in medium and larger

communities, but their expansion in smaller communities was comparatively

minor.

23

23

All measures throughout this section are defined based on the marketing carrier.

EC2020036 29

Compared to legacy carriers, non-legacy carriers draw a lesser share of their

passengers from smaller communities. Further, the share of non-legacy carriers’

passengers originating in smaller communities has declined. In 2006, legacy

carriers drew 18.0 percent of their passengers from smaller communities, while

non-legacy carriers drew 14.2 percent. By 2017, the proportion of legacy carriers’

passengers originating in smaller communities increased slightly to 18.3 percent,

while that of non-legacy carriers’ fell to 11.7 percent. Table 3 displays the share of

passengers drawn from each of the community size groups for legacy and non-

legacy carriers in 2006 and 2017.

Table 3. Percent of Passengers by Community Size for Legacy and

Non-Legacy Carriers

Carrier Type

Year

Small

Medium-

Small

Medium

Medium-

Large

Large

Legacy 2006 4.1% 13.9% 27.6% 27.4% 26.9%

2017 4.7% 13.6% 26.0% 28.1% 27.7%

Non-Legacy 2006 2.1% 12.1% 34.8% 23.7% 27.4%

2017 1.7% 10.0% 36.5% 24.6% 27.3%

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

One factor that could explain the differential patterns of non-legacy carrier

service across different community sizes is their network structure. A simple

breakdown of airline network structures may categorize networks as either hub-

and-spoke or point-to-point. Hub-and-spoke networks are characterized by the

presence of a central hub and several spokes branching out from the hub.

Passengers in a hub-and-spoke network are transported between different points

on the network through the central hub. Point-to-point networks do not have a

central hub and passengers are transported directly between different points on

the network. Modern airline networks are most accurately characterized as a

hybrid between hub-and-spoke and point-to-point networks. Figure 17 is a

graphical representation of the two airline network structures from this simple

characterization.

EC2020036 30

Figure 17. Comparison of Airline Networks

Source: OIG-generated

Non-legacy carriers’ networks are more similar than those of legacy carriers’ to

the point-to-point network.

24

Compared to hub-and-spoke networks point-to-

point networks have features that can make it difficult for the carrier to serve

smaller communities. They typically require high-density markets, allowing

carriers to operate routes at a low average cost per passenger. In addition, they

are better suited to carriers which operate a more limited set of aircraft. This

means the carrier may not operate smaller aircraft, which are better suited for

serving smaller communities.

Non-legacy carriers had notably different patterns of network expansion in larger

communities than in smaller communities. These carriers substantially expanded

their networks in medium-sized and larger communities from 2006 to 2017. For

example, the average passenger could choose between 1.48 non-legacy

competitors in 2006 in large communities. This rose to 2.17 non-legacy

competitors by 2017. By comparison, non-legacy carriers only increased their

presence in smaller communities to a minor extent.

The number of legacy competitors declined across all community sizes. For

example, the average number of legacy competitors serving a route in a medium-

small community fell from 2.63 in 2006 to 2.08 in 2017, a decline of 0.55.

Medium-sized communities saw a similarly large decline in legacy competitors,

while larger communities saw a somewhat smaller—but still significant—decline.

The smallest decline in legacy competitors occurred in small communities. Figure

18 is a bar chart that shows the change in effective competitors across

24

In 2017, over 30 percent of passengers on each of the three legacy carriers made a connection on the same carrier.

Among non-legacy carriers, Southwest had the greatest share of passengers (20 percent) connect to another

Southwest flight. Alaska Airlines (12 percent), Frontier Airlines (6 percent), and Sun Country (5 percent) had modest

shares of connecting passengers. The three remaining carriers—Spirit, JetBlue, and Allegiant—had a share of

connecting passengers below 5 percent.

EC2020036 31

community sizes broken out by changes in legacy competitors and non-legacy

competitors.

Figure 18. Change in Effective Competitors, 2006–2017

Note: Number of effective competitors is calculated weighting by the number of

passengers on each route in each year.

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

Overall, as shown in the figure, in larger communities the robust expansion of

non-legacy carriers more than counteracted the decline in legacy carriers. Despite

national consolidation, passengers departing from larger communities could

choose between more carriers in 2017 than in 2006. The number of legacy

competitors also fell in smaller communities, and the number of non-legacy

competitors rose. However, the magnitude of entry by non-legacy carriers was

not as large as the magnitude of exit by legacy carriers. As a result, passengers

flying from smaller communities had fewer carriers to choose between in 2017

than in 2006.

EC2020036 32

Non-Legacy Carriers Differ Substantially

in Their Strategies for Serving Smaller

Communities

Although non-legacy carriers as a whole showed limited expansion into smaller

communities from 2006 through 2017, these carriers differed notably in their

strategies for serving smaller communities. In particular, Alaska Airlines and

Allegiant Air offer significantly more service to small communities than other

non-legacy carriers.

All of the seven non-legacy carriers drew a smaller share of their passengers from

smaller communities in 2017 than in 2006.

25

Further, five of the seven non-legacy

carriers drew less than 1 percent of their passengers from small communities in

2017. The other two carriers—Alaska Airlines and Allegiant Air—differ from the

other five in ways that help explain their greater propensity to serve passengers

in small communities. Table 4 below shows the percent of passengers drawn

from each community size group in 2006 and 2017 for the seven largest active

non-legacy carriers.

25

We restrict this discussion to the non-legacy carriers which were active in both 2006 and 2017.

EC2020036 33

Table 4. Percent of Passengers by Community Size for Non-Legacy

Carriers

Carrier Type

Year

Small

Medium-

Small

Medium

Medium-

Large

Large

Alaska 2006 7.0% 8.7% 24.2% 32.8% 27.2%

2017 5.8% 7.6% 26.3% 32.9% 27.4%

Allegiant 2006 15.6% 27.6% 51.2% 1.7% 3.9%

2017 11.8% 29.5% 42.6% 9.2% 6.9%

Frontier 2006 0.6% 9.2% 59.3% 15.5% 15.5%

2017 0.5% 6.2% 60.7% 18.0% 14.6%

JetBlue 2006 1.0% 9.0% 17.3% 22.7% 50.0%

2017 0.6% 8.3% 21.3% 30.8% 39.1%

Southwest 2006 1.1% 12.0% 39.0% 19.8% 28.1%

2017 0.7% 10.4% 40.8% 21.4% 26.8%

Spirit 2006 0.0% 10.9% 15.6% 52.7% 20.8%

2017 0.3% 7.3% 26.9% 41.2% 24.3%

Sun Country 2006 0.8% 5.9% 19.5% 61.3% 12.6%

2017 0.1% 4.3% 18.0% 61.2% 16.4%

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

Unlike the other six non-legacy carriers, Alaska Airlines sells tickets for flights that

are operated by its own regional subsidiary, Horizon Air, as well as by other

regional partners. In 2017, none of the seven non-legacy carriers operated aircraft

with fewer than 100 seats. However, Horizon Air’s fleet was composed entirely of

76-seat aircraft at that time. This enabled Alaska Airlines to serve small

communities—which may not have sufficient demand to fill larger aircraft—

through Horizon and its regional partners.

26

In 2017, there were six small

communities—four in Washington and two in Northern California—where Alaska

Airlines was the marketing carrier for at least 85 percent of passengers.

There were stark differences between the three ULCC’s service to passengers in

smaller communities. In 2017, Frontier Airlines and Spirit Airlines drew 6.7 and

7.6 percent of their passengers from smaller communities, respectively, while

Allegiant Air drew 41.3 percent. Although Allegiant’s passenger share on all

flights in 2017 was just 2.4 percent, it was 8.6 percent on flights from small

communities and 5.9 percent on flights from medium-small communities. During

26

Alaska Airlines has also marketed flights that were operated by independent regional carriers.

EC2020036 34

that year, Allegiant was present at a total of 81 smaller communities. In 34 of

these communities, its passenger share exceeded 20 percent. Further, in 12 of

these communities Allegiant had the highest passenger share of any airline, and

in 5 of these communities its passenger share was at least 90 percent.

Allegiant built its business around offering infrequent service from smaller

communities to leisure destinations. Passengers attempting to use Allegiant to

reach destinations not served directly by the airline may face difficulties for a few

reasons. First, Allegiant’s routes are often low frequency. For example, in 2017,

more than half of its routes flew three times or fewer per week. Thus, same-day

connections to other Allegiant flights may not have been available. Second,

Allegiant’s operations tend to be seasonal. For example, in 2017, Allegiant had

64.3 percent more departures in July than in September. Third, Allegiant has

based a significant share of their service to mid-sized and larger metropolitan

areas at secondary airports. For instance, Allegiant’s operations in the Orlando,

FL, area are based out of Orlando Sanford International Airport (SFB), while the

community’s primary airport is Orlando International Airport (MCO).

27

Passengers

seeking to connect from an Allegiant flight to almost any other carrier’s service

would need to exit SFB, drive over 30 miles to MCO, and pass through MCO

security screening.

Flying From Smaller Communities Became

Relatively More Expensive, but Lack of Data on

Growing Fees Hinders Analysis

Passengers flying from smaller communities’ pay a price premium, and this

premium has risen significantly in recent years. However, our analysis was limited

by a lack of information on ancillary fees. Certain fees have grown dramatically in

recent years, but are not reflected in DOT data on prices or ancillary fee revenue.

This lack of data could impact the Department’s understanding of both the costs

to consumers and airline industry competition. It could also impact

understanding of the effect on tax receipts supporting the Airport and Airway

Trust Fund (AATF) of airlines’ increased reliance on ancillary fees. In particular, we

conservatively estimate that airlines’ use of booking fees for purchasing tickets on

their websites may reduce AATF excise tax revenue by $60.6 million in 2019

alone.

27

In 2017, Allegiant accounted for 97.9 percent of departures from SFB but had no departures from MCO. Other

carriers had 130,461 departures at MCO compared to 189 departures at SFB.

EC2020036 35

Flying From Smaller Communities

Became Relatively More Expensive

From 2006 through 2017, passengers flying from smaller communities paid a

significant price premium, compared to passengers on similar flights in large

communities. Passengers flying roundtrip from small communities were

estimated to have paid a 21 percent premium in 2005, which rose to 27 percent

in 2017. The premium for medium-small communities rose from 8.5 percent to

15.6 percent over the same period. In contrast, passengers flying from medium

and medium-large communities consistently paid similar prices to passengers in

large communities.

From 2008 to 2010, the price premium associated with flying out of smaller

communities fell to a relative low point, and then fluctuated between 2011 and

2014. However, since 2014, the price premium paid by passengers from smaller

communities has increased steadily, surpassing 2005 levels. Figure 19 is a line

graph showing the percent price premiums by community size. The baseline for

our calculation of these price premiums is large community prices.

Figure 19. Price Premium Percent by Community Size

Note: Baseline is the large community price

Source: OIG analysis of DOT data

We focused on the price premium—the percentage difference between prices

paid in large versus other community size groups—because jet fuel prices varied

EC2020036 36

considerably from 2006 through 2017, and they are a significant component of

airline costs. We estimated these price premiums using quality-adjusted price

indices for the different community size groups. The quality factors accounted for

included: the number of seats per aircraft type; circuity or ratio of miles flown to

miles between the origin and destination, which accounts for the directness of

flights; the distance between communities; the number of trip segments; and the

carriers marketing the flights. See exhibit A for details on our price premium

estimation.

We calculated the prices using the DOT database reporting airfares—the Airline

Origin and Destination Survey (DB1B)—with Government and airport charges

removed.

28

We adjusted the reported fares to include the average ancillary fees—

baggage and change/cancellation fees—on which DOT collects revenue data

through its Form 41 P-1.2. Revenue information associated with other ancillary

fees is not identifiable given current reporting requirements and ancillary fees are

not included in the reported airfares. For example, the booking fee charged by

ULCCs for reservations made online or over the phone is likely incurred by the

vast majority of passengers but is not included in the DB1B. As a result, fares

listed in the DB1B for ULCCs are likely significantly lower than passengers’ cost of

purchasing tickets—even if the passenger does not add ancillary services outside

of the booking fee. If the Department tracked such ancillary fees, it would

improve the accuracy of its information regarding the cost of air travel to

passengers.

Limited Data on Ancillary Fees Could

Limit DOT’s Ability To Oversee Airlines’

Competitive Practices

Lack of data on many ancillary fees and their associated revenue could hinder

DOT’s oversight of the airline industry. Effective economic oversight by the

Department is important to ensure the efficiency of our transportation system.

Airlines’ pricing of ancillary services is also an important dimension of airline

competition. However, DOT does not collect data on these prices. This lack of

information could pose challenges to the Department’s understanding of

competitive practices in the industry.

Pricing of ancillary services is an important consideration for antitrust authorities

evaluating prospective mergers in the airline industry. DOJ raised concerns over a

prospective increase in ancillary fees in its complaints filed against the two most

recent mainline carrier mergers. In its complaint filed against the proposed

28

We obtained this version of the DB1B, the Superset, from Airline Data Inc.

EC2020036 37

merger between US Airways and American Airlines, DOJ stated “…industry

consolidation has left fewer, more-similar airlines, making it easier for the

remaining airlines to raise prices, impose new or higher baggage and other

ancillary fees, and reduce capacity and service.” In this complaint, DOJ stated that

even a modest increase in ancillary fees could cost consumers millions.

29

Likewise,

DOJ’s complaint filed against the proposed merger between Virgin Atlantic and

Alaska Airlines stated that the merger would likely result in higher fees.

30

Consequently, airlines’ offerings and pricing of ancillary services represent an

important aspect of competition in the industry. For example, Alaska Airlines

notes that fee pricing is a significant competitive factor in the industry.

31

Also,

growth of ULCCs may exert competitive pressure on mainline carriers, which

influences their product offerings. For example, in 2017, American Airlines

introduced its Basic Economy product to compete with ULCCs.

32

Limited information on the prices paid by passengers for ancillary services could

hamper DOT’s ability to provide adequate information on the flying public’s cost

of air transportation between different communities. The Wendell H. Ford

Aviation Investment and Reform Act

33

requires covered airports to produce a

written competition plan to gain approval for passenger facility charges (PFC) and

as a condition of certain grants. Airports’ competition plans are required to

incorporate information on airfares and how they compare to airfares at other

airports, using DOT data. The Department also releases a quarterly report that

provides information on airfares across city-pair markets. Air carriers differ

substantially in terms of the airports and routes they serve, as well as the share of

revenue they earn from fees for ancillary services. As a result, reported airfares

may closely approximate passengers’ full cost of flying from some communities,

but understate it for communities served by carriers that draw substantial

revenue from ancillary fees.

Without supplementary data on ancillary fees and their associated revenues, the

Department’s airfare data also may not accurately capture changes in the cost of

air travel to the public over time. From 2010 to 2018, airlines introduced new fees

for ancillary services such as seat selection and online booking. If the average

charge incurred by passengers for such ancillary services has risen, comparing

29

Amended Complaint, U.S., et al. v. US Airways Group, Inc., et al., 38 F.Supp.3d 69, No.13-cv-1236 (D.D.C. 2014)

30

Complaint, U.S. v. Alaska Air Group, Inc., et al., No. 16-cv-02377 (D.D.C. June 23, 2017) (unpublished).

31

Alaska Air Group Inc., 2017 Form 10-K, (2018).

32

American Airlines Group Inc., 2017 Form 10-K, (2018).

33

P.L. 106-181, section 155. Covered airports include any commercial service airport that has more than 0.25 percent

of the total number of passenger boardings each year at all such airports and where one or two air carriers control

over 50 percent of passenger boardings.

EC2020036 38

airfares over time may not accurately convey changes in passengers’ cost of

flying over time.

34

Increases in ancillary fees may cause the cost of flying to change, even if airfares

remain the same. For example, we queried Spirt Airlines’ website in both March

and August of 2019. For each query, we selected a round-trip itinerary from

Baltimore/Washington Thurgood Marshall International Airport (BWI) to Boston

Logan International Airport (BOS).

35

For the March query, the total cost to a

purchaser was $106.60. For the August query, the total cost was $112.60. A

$6 increase—from $39.98 to $45.98—in the booking fee was the only component

of the total price that changed. Table 5 below displays the results of the queries.

34

For example, Airlines For America’s webpage lists the average domestic round-trip airfare in the United States over

time. They present both a “Base Fare” as well as an “All-In Fare”. The latter incorporates the average baggage and

change/cancellation fees using data from DOT’s Form 41 Schedule P-1.2. This data shows that while the average

baggage and change/cancellation fees increased from $5.88 to $23.47 from 2007 through 2009, the average baggage

and change/cancellation fees declined slightly from $23.47 to $21.85 from 2009 through 2018. However, because this

data does not account for any other ancillary fees such as seat selection or booking fees, it does not completely

represent the change in costs incurred by passengers from 2009 through 2018.

35

The outbound leg for each query was Flight 1028, which was scheduled to depart BWI around 6 a.m. and arrive in

BOS around 7:30 a.m. The inbound leg for each query was Flight 1027, which was scheduled to depart BOS around

10 p.m. and arrive at BWI around 11:30 p.m. The queried itineraries do not include any ancillary services other than

the booking fee.

EC2020036 39

Table 5. Example of Price Components for Travel on Spirit Airlines, March and

August 2019

Price Type Price Component Query 3/8/2019 Query 8/21/2019 Difference

Total Round Trip

Price

All $106.60 $112.60 $6.00