Civil Aviation Authority

Stansted – Market Power

Assessment:

Non-confidential Version

The CAA’s Initial Views – February 2012

Civil Aviation Authority 2

Civil Aviation Authority 3

Table of contents

Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 5

Rationale and context for the CAA‟s airport market power assessments ...... 5

The extent and nature of Stansted‟s market power ....................................... 5

Way Forward .............................................................................................. 14

1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 15

Rationale and context for the CAA‟s airport market power assessments .... 15

The CAA‟s approach to the assessing airport market power ....................... 16

Way Forward .............................................................................................. 16

2. The markets in which Stansted competes .............................................. 19

Stansted‟s business .................................................................................... 19

The use of market definition ........................................................................ 20

Product market definition ............................................................................ 21

Geographic market definition ...................................................................... 34

The interdependence of demand from different user groups ....................... 46

3. Factors contributing to Stansted’s market position .............................. 49

Introduction ................................................................................................. 49

Market shares ............................................................................................. 49

Airline switching .......................................................................................... 52

Passenger switching ................................................................................... 56

Implications of passenger and airline switching and the multisided

nature of the market.................................................................................... 63

Airport sensitivity to passenger and airline switching .................................. 65

Buyer power ............................................................................................... 69

Entry and expansion ................................................................................... 80

Capacity constraints ................................................................................... 81

Pricing and behaviour ................................................................................. 84

Cargo ......................................................................................................... 92

Long term view ........................................................................................... 92

Overall assessment of market power .......................................................... 94

Civil Aviation Authority 4

Civil Aviation Authority 5

Executive Summary

Rationale and context for the CAA’s airport market power assessments

1. Where airports enjoy high levels of market power, it can be appropriate for

the CAA to apply economic regulation, so as to improve outcomes for

passengers, cargo shippers and airlines.

2. The CAA is committed to ensuring that its regulation of airports promotes

choice and value for consumers, whilst also meeting the better regulation

principles. In order to deliver on this commitment, during 2011 the CAA

embarked upon a project to understand the extent and nature of market

power held by the airports that are currently „designated‟ for price control

regulation: Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted.

3. This document sets out our work to date to understand the market power

held by Stansted. These views are based on the evidence currently available

to the CAA. As noted above, we expect that additional evidence will become

available before the CAA takes a firm view on the position of each airport.

Reflecting this, there are a number of issues that have been left open and,

whilst the CAA has sought to highlight where the airport might sit on the

market power spectrum, it has not reached a definitive view at this stage.

4. We would like to thank those stakeholders who have engaged with the CAA

during 2011, and invested time and money in providing evidence and

analysis.

The extent and nature of Stansted’s market power

5. The first step in assessing an airport‟s market power is to consider the

markets in which it operates with regard to its various user groups to

establish a frame of reference within which to conduct the analysis.

Market definition

6. Stansted provides infrastructure and infrastructure services to its various

groups of users, including passenger airlines, passengers, and cargo

carriers, and also retailers and car park operators. Each of these user groups

could be considered as different „sides‟ of the airport market; each with its

own characteristics and ability to respond to changes in the price and service

offered by Stansted.

1

7. In order to understand the market position of Stansted, it is important first to

consider the characteristics of the airport‟s users including the choices

available to them to reduce their use of the airport. As a next step, the

interactions and interdependences between the choices made by these

different airport user groups need to be analysed to reach a view on their

combined impact on the airport.

1

This treatment of airports as operating in a multi-sided market is described in more detail in the CAA‟s

Guidance on assessing airport market power

Civil Aviation Authority 6

Provision of services to passengers

8. The focus on Stansted on low-cost carriers has implications when defining

the market within which the airport competes for passengers. In particular,

there is a degree of uniformity in the requirements of the various passenger

types at Stansted, and limits on the extent to which the airport can segregate

its offer to passengers or price discriminate between them.

9. We have, therefore, adopted a product market for passengers at Stansted

that covers the provision of services for the reception, processing and

boarding of passengers, without differentiating between passengers based

on their individual characteristics.

10. In order to establish a geographic market for the supply of services to

passengers, we consider a range of evidence, including a number of different

ways to define an airport catchment. This showed that there were significant

overlaps between the catchment areas of Stansted and all of the major

London airports, and that they all draw a significant proportion of their

passengers from the Greater London area. These overlaps, when combined

with the location of the airport and evidence on passenger responsiveness,

supports the view that the relevant geographic market covers the South East

of England, Greater London and includes a number of districts falling in the

East Anglia planning region.

Provision of services to passenger airlines

11. Stansted predominantly serves low cost, short haul, point to point airlines.

The airport provides these airlines with a mix of services, including facilities

and services for the handling of passengers and those for the transportation

of bellyhold cargo, although this is currently not a major requirement of

airlines at Stansted.

2

12. These services are likely to be available at most mid-sized airports, which

implies that there are a relatively large number of airports within the same

(airline-facing) product market. However, due to the complexity associated

with operating from larger airports, and the difficulty in achieving quick aircraft

turnarounds, we do not consider Heathrow to be a close substitute to airlines

at Stansted, and that it falls outside of the product market.

13. The demand for capacity at Stansted is significantly higher in the early

morning period than throughout the majority of the rest of the day. This

reflects the particular requirement of based aircraft for access to an early

morning slot – in order to deliver a sufficient number of rotations to deliver

high aircraft utilisation – whereas the demand from aircraft operating their

services into Stansted (inbound carriers) is more spread out. Combined with

this, the airport can vary its charging structures in ways that particularly affect

based or inbound carriers, including by varying charges by the time of day, or

through varying overnight parking charges. Although it currently does not do

so.

2

Most passenger flights at Stansted do not carry cargo. Less than 1% of Stansted‟s cargo is carried

bellyhold (CAA airport statistics).

Civil Aviation Authority 7

14. If airlines are unable to vary their use of the airport at peak, this might

support defining a separate market for the supply of peak capacity. At this

stage, the CAA has not been able to reach a definitive view on this issue –

which is likely to be important to the overall market power assessment – and

has left this issue open at this stage.

15. The geographic market within which Stansted competes for airlines is

determined, to a considerable extent, by the fact that the airport

predominantly serves short-haul, low cost point-to-point carriers. The

business model of these airlines tends to involve basing aircraft at airports of

different sizes across Europe from which they offer point-to-point services.

16. This has a number of implications. First, airport charges are also typically a

higher proportion of their overall cost base than other carriers, suggesting a

higher degree of responsiveness to a given price change than for airlines

with other business models. Second, the largest airlines at Stansted have a

relatively large number of existing bases across Europe, and a large number

of airports to which they already operate, which will tend to reduce the costs

associated with moving capacity away from Stansted. However, the airlines

at Stansted emphasise the importance of Stansted (and of serving London)

to their businesses, and the impact that switching away from Stansted has on

their yields. Airlines have also highlighted the lack of responsiveness to

recent increases in the level of charges at the airport, which is discussed

below.

17. Overall, given the business model of airlines at Stansted and the likely

magnitude of switching costs, airports in the Southeast of England are likely

to be very close substitutes to Stansted (although Heathrow is likely to fall

outside of this market, due to its particular operational characteristics).

3

Furthermore, it appears that the switching of marginal airline services is likely

to take place over a broader area, such that the geographic market relating to

the supply of services to airlines is likely to be European wide.

Provision of services to cargo carriers

18. Stansted provides infrastructure and infrastructure services to cargo-only

carriers for the air transportation of cargo. This includes the provision of

runway and apron space, as well as providing access to cargo-handlers,

access to warehousing facilities, and infrastructure to allow the efficient

onward transfer of cargo. In general, we consider that the airport operates in

a very broad market, and competes with a number of airports across the UK

and Europe for much of this cargo traffic.

The markets in which Stansted operates

19. We have described the markets in which Stansted operates, looking at the

airport‟s passenger-facing and airline-facing activities. However, in practice,

these two aspects of the airport‟s operations are closely linked and there are

important interactions between passengers and airlines that are likely to

affect the overall assessment of airport market power.

3

This is discussed in the context of the product market.

Civil Aviation Authority 8

20. In particular, whilst there may be relatively low direct costs associated with an

airline relocating to another airport, the willingness to do so will be affected

by whether there are sufficient passengers at alternative airports and whether

airline switching away from Stansted typically involves airlines accepting a

lower yield. To the extent that airlines are able to switch to nearby airports

and attract many of the same passengers, this may reduce the adverse

impact on yields. Similarly, for passengers to view an airport as a reasonable

substitute they will need to be able to find a suitable alternative flight, which

will often need to be to the same destination. The airlines‟ ability to switch

will, therefore, depend upon passenger decisions, whilst passengers‟ choices

are likely to be affected by those of airlines.

21. There are two characteristics of an airport that may strengthen the interaction

between passengers and airlines: a high concentration of network carriers or

a small airport that is trying to become established. As Stansted does not

currently serve network airlines and is a relatively large and well-established

airport – indeed, survey evidence confirms a high awareness of the airport

amongst passengers – neither of these conditions appear to apply, limiting

any affects on the market power enjoyed by the airport. However, the retail

revenues generated from passengers are likely to have a significant impact

on the airport‟s incentives to raise prices to airlines, due to the adverse

impact that lower passenger numbers have on the profitability of the airport.

Market shares

22. Market shares can provide an indicator of an airport‟s market position. Even

under the narrowest definition, when we limit the market to be short haul

flights from the London area, Stansted does not have a high market share,

when viewed as a stand-alone airport, and certainly below the level at which

there would be a rebuttable presumption of dominance. However, Stansted

and Heathrow are both currently owned by BAA, and combining the market

shares of the two airports gives very high market shares and which on a UK-

wide basis are still as high as 58 per cent.

23. An important aspect of understanding market power at Stansted is to

consider the position of the airport at the early morning peak. Looking only at

peak periods increases Stansted‟s market share to 26 per cent (behind

Heathrow and Gatwick‟s 30 per cent), and a combined share with Heathrow

of 56 per cent. On some measures, the combined share of BAA-owned

airports would support a rebuttable presumption of dominance.

Airline switching

24. The predominant airline business model at Stansted is low-cost, short-haul,

point-to-point. In general, these airlines will have invested less at the airport

than other airline business models, have multiple bases across the UK and

Europe and, due to their more streamlined cost structure, face airport

charges that generally account for a bigger proportion of the total costs than

they do for full-service network airlines. This implies that there will be a

greater incentive, and more ability, for low cost point-to-point airlines to

switch in response to a given increase in airport charges, which is consistent

Civil Aviation Authority 9

with evidence that highlights that the major carriers at Stansted operate

particularly dynamic networks, with the routes flown varying to a significant

degree over time.

25. Even if switching costs are low enough to allow airlines to switch, they must

have appropriate alternative airports to switch to. A based carrier at

Stansted‟s ability to switch to neighbouring airports may be limited by

constrained capacity at other London airports, but those airlines with a

network of bases across Europe also have the option of switching to other,

non-London airports.

26. The likely magnitude of switching costs, and the sensitivity to airport charges,

is mirrored by the evidence of airline switching. In recent months, Stansted

has lost several major airlines to Gatwick (Norwegian, Air Berlin and Air Asia

X), despite their being some capacity constraints at Gatwick. In addition,

easyJet has recently announced its intention to move some of its based

aircraft from Stansted to Southend.

Passenger switching

27. We have considered a range of evidence to understand the extent to which

passengers might switch between airports. Analysis based on airport

catchment areas highlights the significance of catchment area overlaps,

particularly over the most densely populated areas (notably Greater London).

This suggests that a significant proportion of passengers are likely to be

marginal, and able to switch away from Stansted, if a suitable service is

available at an alternative airport.

28. Survey evidence is consistent with this general finding, showing that there

are significant numbers of Stansted passengers who have previously used

another London airport (indicating a degree of willingness to travel to use

these airports) and that stated that they had considered alternative airports to

Stansted. This is consistent with the survey results that indicated a higher

degree of price sensitivity at Stansted and Gatwick, when compared to

Heathrow.

29. However, this apparent willingness to switch between airports relies upon

passengers being able to find a suitable service at an alternative airport. In

this respect, whilst Stansted has fewer route overlaps than other London

airports, 74 per cent of passengers at the airport could fly to their chosen

destination from another London airport. This suggests that a large

proportion of passengers are likely to have the willingness and ability to

switch away from Stansted.

30. Further, as only around 10 per cent of Stansted‟s passengers were on

regularly-served routes served by more than one airline at Stansted, it is

likely that should an airline remove a service from Stansted, the airport would

be more likely to lose the passengers from that route to another airport.

Indeed, the interplay between passenger and airline decisions means that

the loss of business to an airport resulting from an increase in price may be

greater than indicated by the impact on „marginal‟ passengers, as services

Civil Aviation Authority 10

become unprofitable and prompt those who would have used these services

to consider using another airport.

Airport sensitivity to airline and passenger switching

31. In order to understand the impact that passenger and airline switching is

likely to have on the airport, it is useful to consider the volume reduction (or

„critical loss‟) that would render an increase in prices unprofitable. CAA

calculations suggest that to render a 5 to 10 per cent price rise unprofitable

the airport would need to experience a fall in passenger numbers of between

3 and 11 per cent, depending on the assumptions used. For example, if the

price increase applies to the airports overall revenue, a 5 per cent increase

would be rendered unprofitable if the airport lost approximately 900,000

passengers, or approximately 1,000,000 passengers if operating costs are

saved as passenger numbers fall.

32. Easyjet commissioned Frontier Economics to analyse the potential for airline

switching to constrain prices at Stansted, undertaking similar calculations to

those set out above. Frontier‟s paper shows that airlines switching and

passenger switching would be insufficient to render a 10 per cent increase in

charges unprofitable. However, whilst this analysis makes a useful

contribution to the available evidence, the approach taken restricts

passenger and airline switching in a number of ways that are likely to under-

state the actual level of switching. In addition, the data made available to

Frontier introduces a further potential source of bias, in that it is based on

average easyJet route profitability, rather than the profitability of the most

marginal services.

Buyer power

33. Ryanair and easyJet account for a very large proportion of passengers at

Stansted, with 68 and 21 per cent shares respectively. Further, whilst

Stansted is no doubt an important base for both airlines, the airport accounts

for a much lower proportion (17 and 8 per cent) of the airlines‟ passengers.

This implies that Stansted is significantly more reliant on Ryanair and easyJet

than these airlines are reliant on the airport, and that there could be a degree

of buyer power at the airport.

34. Analysis undertaken for Ryanair by RBB disputes the view that there is a

degree of buyer power at the airport. The RBB paper cites the evidence of

actual switching that took place following the increase in airport charges

faced by Stansted when its agreements with the airport expired, emphasises

the importance to buyer power of having an ability to switch, and also argues

that there are significant costs to Ryanair relocating aircraft across its

European network. Whilst we agree that buyer power requires the

combination of scale with the existence of an ability to switch away from the

airport, we consider it likely that both Ryanair and easyJet have the ability to

switch volumes away from the airport. Indeed, the significant number of

bases operated by the two airlines, and recent examples of the airlines

opening new bases – including the example of easyJet‟s switch to Southend

Civil Aviation Authority 11

– highlights that there is a significant degree of potential switching from these

two airlines.

Competitive price level

35. The interpretation of the evidence on airlines‟ historical responses to price

increases is affected by the relationship between historical prices and the

competitive price level. This is particularly important in light of the very

significant increase in prices paid at the airport during 2006 and the relatively

moderate reductions in volumes that followed.

36. In order to understand whether these price rises were increases towards, or

increases above, the competitive price level we have considered a range of

sources of evidence.

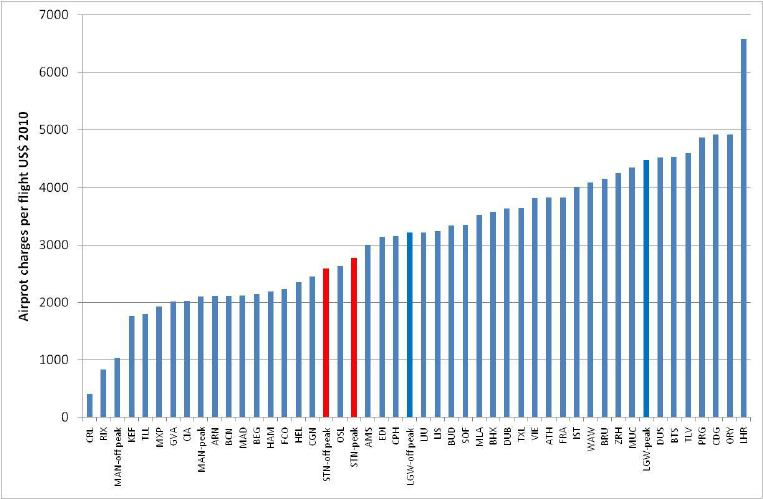

37. Ryanair provided evidence that showed that its charges at Stansted are

considerably higher than at many of the other airports it operates from.

However, when Stansted‟s average charges are compared to those at

comparator airports, it reveals that the level of historical charges was

particularly low and that the recent price levels are broadly in line with a

number of potential comparators. On balance, it appears that the increase in

charges around 2006 was an increase towards, rather than above, the

competitive price level – in which case, we would not expect there to have

been a particularly significant response from airlines switching away from the

airport.

Entry and expansion

38. Expansion and/or entry by existing aerodromes may represent a source of

competitive constraint, albeit one that is limited by the cost and timescales

involved. However, there is relatively limited evidence of significant

expansion and/or entry in Stansted‟s market, with the notable exception of

the planned easyJet expansion at Southend Airport, which involves a

relocation of capacity from Stansted to Southend.

39. At the time of writing, plans are also being discussed for the expansion of

Luton Airport.

Capacity constraints

40. It is clear that there is significant capacity off-peak at Stansted, albeit that this

might reduce over time, as demand grows. However, at peak times, there is

very little spare capacity. The period over which these capacity constraint

holds is currently somewhat limited, relating to 2 or 3 hours, but as demand

grows these constraints would be likely to spread to other hours.

41. Capacity constraints at early morning times appear to be a feature at Luton,

Gatwick and a number of other European airports. This lack of early morning

capacity might reduce the ability of airlines to relocate operations from

Stansted, although Gatwick – which is relatively full by European standards –

has been able to accommodate a number of new airline services, including a

number of services switching from Stansted.

Civil Aviation Authority 12

Pricing and behaviour

42. As discussed above, evidence from Ryanair and from other sources paints a

somewhat different picture about the appropriateness of Stansted‟s current

prices. However, in general terms, the available evidence tends to support

the view that the current price level is reasonable. It is also notable that the

airport has flexibility to raise its prices at peak times but has chosen not to do

so.

43. The airport has, however, seen a considerable fall in passenger volumes,

falling below 18 million, which is back down to 2003 levels. This significant

reduction in airline use of the airport follows the increase in charges at the

airport, but also coincides with a recession in the UK, and low levels of GDP

growth across Europe. Consequently, the reduction in traffic at Stansted

could either reflect economic trends or price responsiveness. In this respect,

Ryanair says that the fall in traffic is as a result of Stansted failing to offer

sufficient discounts, which arguably implies that airlines do have choices of

where to expand and at least some ability to switch away when Stansted‟s

relative prices go up.

44. We have also considered whether the airport has responded to the reduction

in traffic, and the availability of substantial capacity off-peak, by offering

aggressive discounts for growth. The evidence provided by Stansted

appears to support the view that it is offering „competitive‟ discount offers to

support growth in off-peak periods.

45. Overall, the evidence currently available supports the view that there is no

SMP relating to the off-peak periods.

Evidence of market power at peak

46. Capacity in early morning periods appears to be particularly important for the

low-cost carriers at Stansted. There are capacity constraints at these peak

periods at Stansted and also at Luton and Gatwick. This lack of capacity at

this crucial time of day may make switching based aircraft away from

Stansted more difficult.

47. Nonetheless, switching may take place, but it is likely to be more costly to

obtain slots at this time. []. Airlines are generally able to obtain the slots

they want through slot trading, albeit that the slots at the more popular times

are likely to be more expensive.

48. Overall, there remains significant uncertainty about the balance of negotiating

power at peak periods, with the incumbent airlines at Stansted placing

particular weight on capacity at these times, whilst there are also constraints

at a number of alternative airports. Set against this is the general flexibility of

the business models of the airlines that use Stansted at peak periods, and

the fact that the airport is not currently exercising its ability to increase prices

in these periods.

49. On the evidence currently available, Stansted‟s market power at peak

periods could amount to a position of SMP. In order to investigate further this

aspect of Stansted‟s market position, we expect to seek additional

Civil Aviation Authority 13

information on airline switching costs, including on the impact that route

profitability might have on these switching costs.

Impact of common ownership with Heathrow

50. As noted above, Stansted and Heathrow are still currently under joint

ownership. It could therefore be argued that Stansted‟s competition for

certain airlines is muted by concerns about the adverse impact on Heathrow.

Stansted disputes this view and argues that BAA is neutral to Stansted‟s

competition with Heathrow.

51. However, we consider that there is a marked contrast between the

aggressive marketing of Heathrow and Gatwick to passengers and the

relatively low-key approach adopted by Stansted, which could be explained

by the continued ownership by BAA.

52. Of course, even if joint ownership were reducing the ability of Stansted to

compete, this is not sufficient to conclude that divestment by BAA would be

sufficient to remove any SMP held by the airport. Rather, that divestment

would lead to a more competitive outcome than continued joint-ownership.

Initial view on the degree of Stansted’s market power

53. At this stage, the supply of capacity at peak times is the most likely source of

any position of substantial market power at the airport, albeit that we remain

concerned that BAA‟s ownership of Heathrow and Stansted could be

reducing the ability of the airport to raise its profile and adopt aggressive

strategies to attract passengers and airlines to the airport.

54. There is, however, a lack of clarity about the ability of airlines to reduce their

use at peak times, and the evidence on pricing at these times. First, peak

capacity appears important to the airlines at Stansted, as it supports the

efficient use of their aircraft, making them reluctant to reduce their use of

peak capacity. This, however, needs to be set against the apparent flexibility

of their business models, which might enable switching to alternative airports.

55. Second, we have seen evidence that supports the view that Stansted‟s

prices, whilst higher than a number of airports across Europe, appear

comparable to those serving major conurbations. Furthermore, Stansted

does not currently price discriminate between different times of day, despite

having the ability to do so.

56. Looking forward, the CAA‟s view on the market power at Stansted will likely

depend upon the following:

The evidence available on the barriers to airlines reducing their use of

Stansted at peak times, including the impact on airline yields; and

Whether, and to whom, the airport is sold by BAA.

57. Whilst the second of these factors is outside of the control of the CAA, we

would hope to be able to work with airlines and the airport to obtain better

information to reach a firm view on the former.

Civil Aviation Authority 14

58. Overall, therefore, we see Stansted as enjoying the least market power of the

three airports being assessed and, whilst the evidence is currently not

sufficiently clear to reach a definitive view, it appears that any position of

substantial market power arises from the relative bargaining positions of the

airport and airlines during a relatively narrow peak period. The relative

strength of these positions might change over time and be affected by the

potential ownership changes at the airport, as well as the balance between

demand and available capacity.

Way Forward

59. We welcome stakeholders‟ views on the information presented in this paper.

The CAA is consulting during 2012 on its views, and will continue to work

with stakeholders to develop its analysis and to resolve the issues that have

been left open at this time. Information about the consultation process,

contact information and the dates for a seminar are set out in chapter 1.

Civil Aviation Authority 15

1. Introduction

1.1 This is the non-confidential version of the CAA‟s Initial Views on the degree of

Stansted‟s market power. Excisions from the text are marked with [].

Rationale and context for the CAA’s airport market power assessments

1.2 Where airports enjoy high levels of market power, it can be appropriate for the

CAA to apply economic regulation, so as to improve outcomes for

passengers, cargo shippers and airlines. This regulation currently takes the

form of a cap on the prices charged by the airport and a series of financial

incentives and other obligations to encourage efficient operation, appropriate

service quality and efficient investment.

1.3 Most UK airports are not subject to this form of economic regulation. Airports

are only subject to this regulation if they have (or are likely to have)

„Substantial Market Power‟ and if economic regulation is likely to improve

outcomes. Further, when airports are subject to such economic regulation, it

can take a number of forms, and be tailored to the extent and nature of

market power.

1.4 The CAA is committed to ensuring that its regulation of airports promotes

choice and value for consumers, whilst also meeting the better regulation

principles. In order to deliver on this commitment, during 2011 the CAA

embarked upon a project to understand the extent and nature of market

power held by the airports that are currently „designated‟ for price control

regulation: Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted. This work also addresses the

Competition Commission‟s view that the CAA should keep competition

between airports under review, and that the economic regulation of Gatwick

and Stansted might need to adapt to facilitate competition.

4

1.5 These assessments will inform the CAA‟s views on whether these three

airports should continue to be subject to economic regulation, including

whether – under the proposed reforms set out in the Civil Aviation Bill (2012)

– these airports should be required to hold an economic licence. The work

will also allow the CAA to work with stakeholders in developing future

regulation of these airports that protects consumers.

1.6 We set out below the initial findings of our work to date to understand the

market power held by Stansted. These views are based on the evidence

currently available to the CAA. As noted above, we expect that additional

evidence will become available before the CAA takes a firm view on the

position of Stansted. Reflecting this, there are a number of issues that have

been left open and, whilst the CAA has sought to highlight where each airport

might sit on the market power spectrum, it has not reached a definitive view

on the airport at this stage.

4

Competition Commission, „BAA Airports Market Investigation – Final Report‟, March 2009, paragraph

10.339.

Civil Aviation Authority 16

The CAA’s approach to the assessing airport market power

1.7 In reaching an initial view as to the degree of market power of Heathrow,

Gatwick and Stansted, we have followed the approach set out in the CAA‟s

Guidance on the assessment of airport market power

5

.

1.8 There has been extensive stakeholder engagement, including with the three

regulated airports as well as Luton and Manchester, and the main airlines of

Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted. This engagement has taken the form of:

meetings with stakeholders to discuss relevant evidence;

stakeholder feedback and discussion on work in progress;

the submission of evidence by stakeholders;

some stakeholders, including both airports and airlines, have

commissioned reports by economic consultancies; and

the CAA‟s stakeholder workshop held on 15 November 2011 to set out

its emerging views.

1.9 We have also published a number of working papers in 2011:

on the general market context

6

;

catchment area analysis

7

; and

passengers‟ airport preferences

8

.

1.10 While undertaking the market power assessments, we also sought the advice

of an economic and a legal consultant.

1.11 The initial views expressed in this assessment are based on the evidence

currently available to us. We expect that additional evidence will become

available before we take a firm view on the position of each airport.

Reflecting this, there are a number of issues that have been left open and,

whilst we have sought to highlight where Stansted might sit on the market

power spectrum, it has not reached a definitive view on the airport at this

stage.

1.12 We would like to thank those stakeholders who have engaged with us during

2011, and invested time and money in providing evidence and analysis.

Way Forward

1.13 We welcome stakeholders‟ views on the information presented in this paper.

There are two periods over which interested parties can engage with the

CAA:

5

CAA Guidance on assessing airport market power

http://www.caa.co.uk/docs/5/Final%20Competition%20Assessment%20Guidelines%20-%20FINAL.pdf

6

CAA UK Airports Market – General Context September 2011

http://www.caa.co.uk/docs/5/20110905%20Market%20Context-FINAL.pdf

7

CAA Catchment area analysis October 2011

http://www.caa.co.uk/docs/5/Catchment%20area%20analysis%20working%20paper%20-%20FINAL.pdf

8

CAA Passengers’ airport preferences – Results from the CAA Passenger Survey November 2011

http://www.caa.co.uk/docs/5/Passenger%20survey%20results%20-%20FINAL.pdf

Civil Aviation Authority 17

Those wishing to share their initial views with the CAA should aim to

submit any material to the CAA by 24 March 2012, so that these can

inform the CAA‟s next Q6 price control publication, which is scheduled

for April 2012.

Those wishing to engage on the detail of the competition

assessments are invited to engage with the CAA during 2012, so that

any additional evidence and analysis can be incorporated in an

updated assessment of airport competition, scheduled for publication in

late 2012/early 2013.

1.14 If you would like to discuss the contents of this paper, and the CAA‟s work on

assessing airport competition, in the first instance please contact Alina

Jardine Goad on 020 7453 6229 / alina.jardinegoad@caa.co.uk or Alexander

Dünki on 020 7453 6212 / [email protected]k. You can also contact

Chris Hemsley on 020 7453 6237 / chris.hemsley@caa.co.uk.

1.15 If you would like to discuss the economic regulation of Heathrow, Gatwick and

Stansted, including the Q6 work programme, please contact Richard Moriarty

on 020 7453 6203 / richard.moriar[email protected]k.

1.16 The CAA will also be hosting a seminar, to take forward the work on price

control design for Stansted, on 16 March 2012. The output of these seminars

– and other discussions with stakeholders – will be brought together into a

publication in April 2012, which will frame the debate on the development of

regulation and, where appropriate, support the process of Constructive

Engagement. If you would like to register your interest in the seminars,

please contact Barbara Perata-Smith, on 020 7453 6202 or

Barbara.PerataS[email protected]k.

1.17 There will also be an opportunity to engage on the CAA‟s initial views on

airport market power during 2012, which will also allow the CAA to work with

stakeholders to narrow down those areas of uncertainty that currently exist.

Stakeholders will also be able to submit further evidence – and comment on

the CAA‟s initial views – during this period. At this stage, the CAA expects to

publish its next substantive analysis of airport market power in late 2012/early

2013.

Civil Aviation Authority

18

Civil Aviation Authority

19

2. The markets in which Stansted competes

2.1 This chapter describes Stansted‟s business, its infrastructure and the

customers it serves. It looks at the varying requirements of different customer

groups and then goes on to analyse the product and geographic markets for

Stansted.

2.2 Reflecting the importance of the linkages between Stansted‟s various

customer groups, the final section of this chapter brings together the previous

sections and draws out the implications of these interrelations for market

definition.

2.3 We note that there is a degree of repetition in the evidence cited in this

chapter and in chapter 3. This reflects the fact that both chapters are seeking

to understand the strength of the competitive constraints on Stansted.

Stansted’s business

2.4 Stansted provides infrastructure and infrastructure services to its various

groups of users, including passenger airlines, passengers, and cargo carriers.

Each of these user groups has its own characteristics and infrastructure and

service requirements from Stansted, which are described below.

Provision of products and services to passengers

2.5 Stansted provides infrastructure and infrastructure services to passengers,

including:

aeronautical services, including security clearance and flight

information and surface access infrastructure; and

non-aeronautical services, including retail space and car parking.

2.6 Stansted does not currently directly charge passengers for the use of the

airport.

9

However, it nevertheless supplies a number of services to

passengers in their use of the airport and can vary its offering in ways that

vary the attractiveness of the airport to passengers. It also charges

passengers directly for the use of their car parks.

Provision of products and services to passenger airlines

2.7 Stansted also provides aeronautical and non-aeronautical infrastructure and

infrastructure services to passenger airlines. This includes facilities and

services for the handling of passengers and those for the transportation of

bellyhold cargo, although this is currently not a major requirement of airlines

at Stansted.

10

2.8 These services include:

aircraft-related aeronautical services (e.g. facilities for landing, parking,

and taking-off of aircraft);

9

There is no statutory prohibition on the airport choosing to charge passengers. Indeed, a number of

regional airports in the UK (and a number of major airports overseas) impose charges directly on

passengers, in the form of „Airport Development Fees‟ and „Passenger Facility Charges‟.

10

Most passenger flights at Stansted do not carry cargo. Less than 1% of Stansted‟s cargo is carried

bellyhold (CAA airport statistics).

Civil Aviation Authority

20

airline-facing non-aeronautical services (e.g. information technology

services, check-in desks and Common Use Self-Service (CUSS)); and

2.9 providing access to staff and supporting services procured by airlines (staff

security clearance, staff car parking, access to groundhandlers, access to

catering suppliers, etc).

2.10 We are adopting a working assumption that all of these services should be

included in the product market within which Stansted operates, as the failure

to supply any one of these services would severely hamper the economic

operation of a passenger airline, which means that any market power enjoyed

by virtue of the ownership of the runways, taxiways and terminals would also

be likely to be enjoyed over all of these services.

11

2.11 Airports also provide other services that are, to a greater or lesser degree,

ancillary to the operation of passenger services, such as office rental to

airlines or tour operators, either within terminals or at nearby locations. We

are adopting a working assumption that the provision of these services forms

part of a wider market for, in this case, office space.

Provision of products and services to cargo carriers

2.12 Stansted provides infrastructure and infrastructure services to cargo-only

carriers for the air transportation of cargo. This includes the provision of

runway and apron space, as well as providing access to cargo-handlers,

access to warehousing facilities, and infrastructure to allow the efficient

onward transfer of cargo.

Provision of access to Stansted’s infrastructure and services to third party service

providers

2.13 Many services for airport users are provided by third party service providers.

For airlines and cargo carriers, these service providers (contracted by them)

include ground- and cargo-handlers respectively, and maintenance and repair

operations.

2.14 For passengers, these service providers include food and drink, and providers

of other retail services (e.g. bureau de change). In order to provide these

services, suppliers typically need to rent terminal space and to obtain access

to the landside and airside facilities for their staff and to bring in stock.

The use of market definition

2.15 Defining the relevant market is usually the first step of any competition

assessment. It provides the context for the analysis by setting out the relevant

set of products and geographic areas which encompass the closest

substitutes for the products and services of interest.

2.16 However, as noted in our guidelines, market definition is not an end in itself,

but rather provides a frame of reference for the analysis of competitive

effects.

11

We note here that access to the airport, the construction and operation of its terminals and runways

are all controlled by Stansted Airport.

Civil Aviation Authority

21

2.17 In practice, in differentiated product markets, it can be difficult to draw a line

around a group of products with a varying degree of competitive constraint on

each other to define the market. In such circumstances it is appropriate to

consider the degree of competitive constraints faced by the product in

question in the round, regardless of whether they arise from within or outside

a defined relevant market.

2.18 Markets are generally defined in two dimensions: product and geographic.

The CAA‟s Guidelines set out the basis on which we have carried out the

market definition analysis. It should be noted, in particular, that in the absence

of sufficient data and given the difficulty in establishing the competitive price

level, rather than carry out a quantitative hypothetical monopolist test we have

assessed available evidence on the products supplied by the airport and

airline and passenger preferences using the principles of the test.

2.19 In particular, we have looked at the ability of airlines and passengers to switch

their business away from the airport, the ability of other airports to begin

supplying a substituted product to that of Stansted and the effect of these

factors of the profitability of any price rise by Stansted.

2.20 The CAA‟s approach is set out in more detail in the CAA‟s Guidance on the

Assessment of Airport Market Power.

12

2.21 The remainder of this chapter considers the product and geographic market

definitions from the perspective of airlines and passengers, looking at both

demand and supply side substitutability. We then draw this evidence together

and consider the effects of the interdependence of demand from the different

user groups and the implications of this on overall assessment of the markets

in which Stansted operates.

Product market definition

2.22 The following section considers each of Stansted‟s main customer groups. It

looks at the characteristics of these groups and whether there are separate

segments within these groups that have different product requirements.

13

2.23 By looking at the choice sets available to each of Stansted‟s customer groups

(and, if relevant, subgroups) on a product dimension and the ability to switch

between the different alternatives, we have assessed the potential for these

customers to react to an increase in charges by the airport. We have then

suggested product market definitions that include all alternatives that

customers can easily switch between.

Passenger demand side substitutability

2.24 A number of passenger sub-groups can be distinguished using various

characteristics:

journey purpose;

12

„Guidance on the assessment of airport market power’, CAA, April 2011

13

We refer to market segments where we want to describe and delineate different groups of airlines and

passengers that are likely to have distinct features. This is not the same as describing these as

separate economic markets; we assess in this paper to which degree there might be separate markets

for different market segments, or to which degree they might suggest one, albeit differentiated, product

market.

Civil Aviation Authority

22

destination; and

passenger origin (inbound, outbound and connecting passengers).

2.25 We consider the relevance of these subgroups at Stansted and whether they

have varying requirements that might imply separate product market

definitions. We then look at passengers‟ ability to switch away from the

airport.

Journey purpose

2.26 One way to distinguish passengers is by their journey purpose. Figure 1

below shows the passenger breakdown by passenger origin

14

(UK or foreign

and journey purpose at Stansted (Holiday, Visiting Friends and Relatives

(VFR), or Business).

Figure 1 Passenger breakdown by passenger origin and journey purpose

Source: CAA analysis of the CAA Passenger Survey (2010)

2.27 Stansted serves both business and leisure passengers. Despite the fact that

its airlines do not generally offer a premium service, 16 per cent of its

passengers are business passengers. In addition, there is a recent trend

towards a number of airlines offering additional services that might be

particularly attractive to passengers travelling on business, such as priority

boarding and reserved seating, which may lead to an increase in business

travel on these airlines at Stansted.

2.28 In terms of the business/leisure split, it could be argued that the product

market for business passengers may be narrower than that for Holiday and

VFR passengers if they require the airport to provide different services,

service quality and/or infrastructure that only business passengers require.

However, the majority of the airport‟s services are offered to all passengers,

irrespective of their journey purpose. Indeed, there is no direct way for the

airport to distinguish passengers travelling on business from those travelling

for leisure purposes. To the extent that these two passenger groups have

14

The CAA‟s survey asks people to identify where they reside. This is used as a proxy to identify

whether passengers are originating from a UK district, or from overseas.

UK BUS

9%

UK HOL

22%

UK VFR

26%

O/S BUS

7%

O/S HOL

16%

O/S VFR

20%

Civil Aviation Authority

23

different car parking needs, for example business passengers are likely to

have more of a preference for short stay or valet parking, there may be some

potential for price discrimination here, but we do not consider this sufficient

enough to warrant separate market definitions.

2.29 Stansted does provide some services – through third-party suppliers – that

are particularly likely to be attractive to passengers travelling on business,

such as fast-track security and premium lounges. These facilities are not

restricted to business passengers and, given that business passengers can

choose whether to purchase these extra services, there does not appear to

be a strong rationale for identifying a sub-market for the provision of airport

services to business passengers.

2.30 A very large proportion (84 per cent) of Stansted‟s passengers are travelling

for leisure purposes, which can be split into those travelling for a Holiday (38

per cent of Stansted) and for VFR (46 per cent). This highlights that Stansted

has a particularly high proportion of its traffic accounted for by VFR traffic,

relative to other UK airports.

2.31 In general, passengers travelling for VFR purposes are less flexible in terms

of their destination than those travelling on a holiday, who may be able to alter

their destination. However, we have not identified any strong reason why

holiday and VFR passengers would consume different airport services (albeit

that the retail spend between these groups may differ).

2.32 Furthermore, individual services will typically have a mix of Holiday and VFR

(as well as business) passengers, making it difficult for the airport to

discriminate between these passengers. Consequently, there does not

appear to be a strong rationale for identifying a sub-market for the provision of

airport services to either Holiday or VFR passengers.

Destination

2.33 The vast majority of Stansted‟s passengers are short-haul, with only two per

cent travelling to long-haul destinations. This means that to understand the

market power of the airport, it is important to understand the characteristics of

short-haul passengers. Indeed, the very high shares of passengers

accounted for by short-haul flights implies that there is unlikely to be any need

to define a sub-market by destination type.

2.34 This focus of Stansted‟s operations on short-haul services has implications for

the choices available to passengers. In particular, short-haul passengers

typically face a wider choice set than long-haul passengers, as there are more

airports offering short-haul services and are more route overlaps between

short-haul services at different airports. In addition, for those passengers who

are flexible on their destination airport

15

there are more short-haul

destinations, at more airports, increasing the choice set further.

15

Some passengers might be seeking a “city break”, “ski holiday” or “Spanish beach holiday” and be

willing to choose between services to a similar type of destination.

Civil Aviation Authority

24

Passenger origin (inbound, outbound and connecting passengers)

2.35 Stansted provides services to both departing/outbound and arriving/inbound

passengers. The infrastructure services required by inbound and outbound

passengers differ somewhat, as outbound passengers typically have access

to more significant (airside) retail offerings, and also require security

clearance. However, there is a significant overlap in the services offered to

these two groups. Furthermore, given the significant proportion of

passengers who travel through the same airport for both legs of their trip, any

attempt to discriminate between inbound and outbound passengers would not

appear likely to be effective, as it would still affect the overall trip cost faced

by passengers. Reflecting this, we do not consider that there is a need to

distinguish between these groups in terms of the product market.

2.36 In respect of how passengers arrive at the airport, the majority of Stansted‟s

passengers arrive at the airport by surface travel, although there is a small

proportion of passengers who connect between services. These passengers

are „self-connectors‟, as the airlines at Stansted do not offer through-tickets or

formally support connections between services. Reflecting this, passengers

do not therefore require transfer facilities, such as airside security clearance

and systems for connecting baggage.

2.37 This lack of connecting passengers, supports the view that the airport is

competing to attract passengers onto point-to-point services, which is

consistent with views expressed to the CAA by the airport and by airlines.

Ability to switch

2.38 The above discussion highlights that the passengers using Stansted share

common key requirements and that there are factors that limit the airport‟s

ability to differentiate its offer in a way that might support a narrowing of the

passenger-facing product market.

2.39 There are few direct costs to passengers switching between airports, other

than the costs involved in travelling to an alternative airport (a factor that is

considered in the context of the geographic market, below).

2.40 However, the ability of a passenger to switch away from the airport will

depend on whether or not a suitable destination is available from an

alternative airport. Whilst the airport can structure its charges in ways that

can encourage particular services (such as targeted discounts to new

destinations), route choice is determined by the airlines rather than the

airport. Reflecting this, we have not identified a strong argument to narrow

the market in terms of different destinations. The impact of route overlaps on

switching is examined in the final section of this chapter.

Summary – Product market: passengers

2.41 In terms of the airport product, there is a degree of uniformity in the

requirements of the various passenger types at Stansted, and limits on the

extent to which the airport can segregate its offer to passengers or price

discriminate between them.

Civil Aviation Authority

25

2.42 In summary, therefore, it seems that the appropriate product market for

passengers at Stansted should be the general provision of airport

infrastructure and infrastructure services to passengers. This is likely to cover

a range of aeronautical and non-aeronautical services that are required for

the reception, processing and boarding of passengers.

2.43 However, the choice set for passengers will depend on whether or not a

suitable destination is available from the alternative airport, which we have

considered in the context of the geographic market, below.

Passenger airlines demand side substitutability

2.44 Airlines‟ infrastructure requirements are likely to differ according to their

business model and the type of service they offer. These differing

requirements may affect the choices available to different airlines and the

airports with which Stansted competes.

2.45 In this section we consider different ways of distinguishing between airlines

and whether this has any implications for product market definition, including:

short-haul vs. long-haul;

airline business model; and

based vs. inbound

2.46 We then go on to consider airlines‟ ability to switch.

Short-haul vs. long-haul

2.47 In 2010, 98 per cent of Stansted passengers‟ final destinations were domestic

or European, with just 2 per cent of passengers flying long-haul, a figure that

is likely to be reduced further by the removal by Air Asia X of its services from

the airport.

2.48 The infrastructure needed to operate a short-haul route versus a long-haul

route are broadly similar, in that all airlines have a minimum requirement in

terms of runways, aprons and terminal facilities. However, long-haul routes

are more likely to be served by larger aircraft – requiring a higher specification

of runway – and they are more likely to carry bellyhold cargo, which can add

to the requirements of long-haul operations, relative to those operating short-

haul.

2.49 However, given that the vast majority of routes from Stansted are short-haul,

it is not necessary to consider any split for market definition purposes

between the supply of infrastructure for short-haul and long-haul services, as

it is unlikely to affect the overall assessment of market power.

2.50 Looking ahead, the airport may attract higher volumes of long-haul services,

which might have implications for the appropriate market definition. We

consider the airport‟s future growth, and efforts to attract additional services,

in chapter 3.

Airline business model

2.51 Stansted predominantly serves low cost, point-to-point airlines. Figure 2

below gives the airline business model breakdown at Stansted over the last

Civil Aviation Authority

26

ten years. This shows that by 2010, at least 94 per cent of Stansted

passengers flew on low-cost carrier (LCC)

16

airlines, with three per cent flying

charter and three per cent full-service carriers (FSC).

Figure 2 Share of Stansted’s passengers by business model, 2010

Source: CAA Airport Stats, 2010

2.52 Given that Stansted does not currently serve FSC or charter airlines to an

appreciable extent (despite Stansted‟s attempts to attract such airlines – see

chapter 3), this implies that the provision of facilities to these airline business

models is unlikely to determine the airport‟s market power. In the remainder

of this paper, we therefore concentrate our analysis on LCCs (operating short

haul, point-to-point services), since it is the interaction between the airport,

these airlines and their passengers that will determine the extent of

Stansted‟s market power.

2.53 In terms of their infrastructure requirements, LCCs have fewer needs to

FSCs, particularly those operating networks with connecting passengers.

LCCs do not require facilities to accommodate transfer passengers and

usually require more basic terminal facilities than FSCs.

2.54 The LCC business models do, however, rely upon achieving high levels of

utilisation of their aircraft, by reducing the time that aircraft are on the ground.

This can be achieved by efficient turnaround times, short taxiing times and

low levels of airfield delay. These requirements can limit – to a degree – the

airports that no-frills airlines view as being reasonable alternatives to

Stansted. In particular, relatively uncongested airports, or those supporting

reliable and efficient turnarounds, may be close alternatives (for this

dimension of comparability).

2.55 Consequently, congested airports or those with relatively high levels of airfield

delays and relatively low levels of punctuality might not be viewed as being

16

We generally adopt the term „low-cost carrier‟ to identify airlines, such as easyJet, Ryanair, Monarch

and Jet2 that operate point-to-point services. These airlines are often referred to as „no frills‟ airlines. In

reality, individual airline business models vary, and we use these terms to differentiate these airlines

from „full-service‟ airlines, that offer different ticket classes, support connecting traffic and tend to

operate using a more diverse fleet of aircraft.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

Low-Cost

Full-Service

Charter

Civil Aviation Authority

27

close alternatives to Stansted. For this reason, we do not consider that

Heathrow is likely to be viewed as a reasonably close alternative airport for

most of the airlines operating from Stansted

17

.

2.56 A further factor that can affect the utilisation of aircraft is the ability of airlines

with aircraft based at the airport to leave early in the morning. Early morning

departures increase the likelihood that the airlines are able to achieve a high

number of rotations each day. This may have implications for the ability of

airline to change their usage pattern of Stansted across the day. This is

discussed in more detail below.

Based vs. inbound

2.57 Another way in which airlines can be distinguished is by whether or not they

base aircraft at Stansted overnight, or whether they are based at another

airport, their first service to Stansted being operated inbound.

2.58 As noted above, the no-frills airlines at Stansted are likely to place a particular

premium on high levels of aircraft utilisation, which means that when they

base aircraft at the airport they will also place a premium on the ability to

depart from the airport early in the morning. This preference for early-

morning departures may also be compounded by the preferences of some

passengers (notably those travelling for business) to leave relatively early, in

order to arrive at their destination in time to carry out a full day‟s work,

although the share of business passengers at Stansted is relatively low.

2.59 In contrast, whilst operators of inbound aircraft might also place a premium on

high levels of utilisation, the differing sector lengths involved in flying into

Stansted spreads the arrival times over a broader period of the day, relative to

the usage pattern of the first wave of departing aircraft.

2.60 So while the demand for slots is more spread out for non-based aircraft, a

based aircraft will have a particular requirement for access to an early

morning slot. This raises the question of whether the airport is able to

differentiate its offer between based and inbound aircraft to such an extent

that they should be considered to be separate product markets.

2.61 In principle, the airport can vary its charging structures in ways that

particularly affect based or inbound carriers, including by varying charges by

the time of day, or through varying overnight parking charges. The airport‟s

ability to differentiate between inbound and outbound services will also

depend upon the extent to which the airlines operating these services can

respond to any price change and reduce their use of the airport. In this

context, it is relevant that the main airlines at Stansted operate both based

and inbound aircraft, and have a number of bases across Europe which

would, in principle, allow them to switch outbound operations to be inbound

(and vice-versa).

2.62 However, a switch between outbound and inbound operation changes the

flight timings that can be offered to passengers. To the extent that local

passengers have strong time preferences, this might act as a barrier to

17

We discuss later the extent to which passengers might still view the two airports as being substitutes.

Civil Aviation Authority

28

airlines switching between inbound and outbound operations. The relatively

low levels of business passengers at Stansted might suggest a higher degree

of flexibility over departure times than at London City or Heathrow, which both

have particularly high proportions of business travellers (33 and 63 per cent

respectively)

18

.

2.63 On the basis of the evidence available, it might be appropriate to distinguish

between the supply of infrastructure to based and inbound operators, in light

of the potential costs associated with switching between based and inbound

operation, and the emphasis placed by airlines at Stansted on operating

based services at peak times. Further analysis of this issue would require

airline data on route revenues, to allow comparisons between outbound and

inbound profitability, so as to understand better the costs of switching an

outbound service to an inbound one. This would allow the CAA to understand

if switching services in this way would undermine an attempt to raise prices

above the competitive level to on or other of these groups.

2.64 These issues are considered in more detail in the context of whether there are

„temporal‟ markets, from paragraph 2.78.

Ability to switch

2.65 The switching costs of airlines are considered in more detail in chapter 3,

however as the ability of airlines to switch away from Stansted will affect the

assessment of the relevant market, we also discuss this issue below (in

respect of those factors that affect the product market) and in the following

section, in the context of the geographic market.

2.66 The airlines at Stansted are predominantly LCC airlines. The infrastructure

and service level requirements of these airlines will tend to be below those of

a FSC airline. As discussed above, LCCs will typically not require facilities to

connect passengers and baggage between flights, or to facilitate the carrying

of bellyhold cargo, or facilities targeted at premium passengers, such as

business lounges.

2.67 Furthermore, the aircraft flown by Ryanair

19

and easyJet

20

can operate from a

wide range of airports across the UK and Europe, albeit that some

commercial airports – such as Southampton and London City – have runways

that do not allow some common aircraft types to operate. These factors

mean that the choice set of the major airlines at Stansted is relatively wide

(below we discuss factors that might limit the ability to exercise these choices,

in the context of the geographic market).

2.68 Indeed, Ryanair, the main airline at Stansted, currently also operates at a

number of much smaller airports than Stansted, which highlights that its

minimum requirements are relatively low and below the level of infrastructure

available at Stansted (with its long runway and cargo facilities). This implies

18

See Figure 14 of „UK Airports Market – General Context‟, CAA, September 2011

19

As at November 2011: 275 Boeing 737 800s (Ryanair Half Year Results, Nov 2011)

20

As at 30 September: 167 A319s, 35 A320s, and 2 Boeing 737-700s (easyJet Annual Report 2011)

Civil Aviation Authority

29

that most mid-sized airports would be appropriate substitutes to Stansted in

terms of the product offering.

21

2.69 Turning to the impact of an increase in airport charges on the airlines

operating at Stansted, airport charges are generally a much higher proportion

of LCC‟s costs than they are for FCCs, and for those operating network and

long-haul services (such as BA, BMI and Virgin). As a result, the airlines at

Stansted are likely to be more sensitive to an increase in airport charges than

many of the airlines operating at Gatwick or Heathrow.

2.70 Figure 3 shows the share of operating costs accounted for by airport-related

costs for the major UK airlines. It illustrates that these costs constitute about

10 per cent for BA and Virgin („VS‟), which is representative of network/long

haul based carriers, and about 20 per cent for bmi and Flybe („FB‟), which is

representative for carriers with a more regional focus and smaller aircraft,

albeit that BMI has a mix of regional, short-haul and mid-haul operations. In

contrast, airport-related costs account for about 30 per cent for easyJet, an

LCC.

22

Figure 3 Shares of operating costs of major UK airlines

Source: CAA airline account information, latest available financial years

23

2.71 Figure 4 shows a summary of easyJet operating costs, which highlights the

importance of costs relating to ground operations (£14.79 per seat flown),

which represents 45 per cent of total operating costs (excluding fuel). This

21

Ryanair currently operates from 160 airports, with 47 bases. easyJet currently operates from 123

airports, with 19 bases.

22

This analysis has been taken from the CAA‟s airline statistics, which only cover airlines registered in

the UK.

23

Figures taken from Table 6 of the 2009/10 airline accounts published regularly on the CAA‟s website:

http://www.caa.co.uk/default.aspx?catid=80&pagetype=88&pageid=13&sglid=13. Airport-related costs

for the purpose of this figure include the following line items: 22, 24, 25, 27. This is likely to include also

costs for services that fall outside the services relevant for this assessment, for example for ground

handling services. Costs charged for relevant services provided by airport operators are therefore likely

to constitute a lower share.

2.7%

4.0%

11.2%

10.4%

18.9%

9.2%

5.3%

7.8%

8.8%

9.6%

4.5%

3.8%

5.9%

4.9%

8.9%

34.6%

21.9%

28.5%

26.2%

15.7%

29.7%

35.9%

18.8%

16.1%

31.0%

19.3%

29.1%

27.9%

33.6%

16.0%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

BA

VS

bmi

FB

EZJ

Other

Fuel

Crew and aircraft related costs

(except maintenence and overhaul)

ANS charges

Other airport-related costs

Airport charges

Civil Aviation Authority

30

compares to the current airport charges at Stansted, which are equivalent to

£7.26 per passenger for 2012/13.

24

Figure 4 easyJet operating costs (excluding fuel)

Source: easyJet Annual Report, 2011

2.72 The airlines operating at Stansted are able to use a large number of other

airports – in operational terms – and have cost structures that mean that they

are more sensitive to increases in airport charges. In addition, the airlines at

Stansted typically make relatively limited investments in facilities at the

airport, particularly when compared to the investments made by full-service

and network carriers. Indeed, both Ryanair and easyJet stress the flexible

nature of their operations.

25,26

2.73 It appears that the costs involved in switching from one airport to another in

terms of the physical move would be limited. It should be noted, that in terms

of market definition and market power assessments, we only need to consider

a switch at the margin, i.e. it would not be necessary for Ryanair to switch its

whole operation at Stansted (which may be considerably more costly) to

another airport, but just a share of its business.

2.74 Consequently, the main barrier to switching is the ability to operate a

profitable route out of an alternative airport and the impact that switching a

route from Stansted to the next-best airport might have on the yields earned

by the airline. This is discussed further in chapter 3.

2.75 For the purposes of the product market definition, this supports the view that

the airlines at Stansted operate in a broad market, and have the flexibility to

use a large number of airports, albeit that there are a small number of

commercial airports where the infrastructure does not support their

operations, due to the capability of the runways. The operational

characteristics of Heathrow, with its congestion, relatively low levels of

punctuality and longer taxiing and airspace delays, suggests that this airport

is unlikely to be a viable alternative for the airlines currently at Stansted.

24

„BAA Stansted Airport Charges – April 2012-March 2013‟, BAA

25

See, for example, interview with Michael O’Leary, retrieved from www.anna.aero, quoted in footnote

75.

26

“easyJet has built flexibility into its fleet planning arrangements such that it can increase or decrease

capacity deployed, subject to the opportunities available and prevailing economic conditions. The

Company also has flexibility to move aircraft between routes and markets to improve ROCE.”, easyJet

Annual Report (pg 11), 2011.

Civil Aviation Authority

31

Summary: product market – passenger airlines

2.76 In summary, the product market definition for Stansted from the perspective of

airlines appears to include any mid-sized airport (or larger) with an

appropriate runway. However, airlines use airports in order to gain access to

passengers and require access to a catchment that is sufficiently large and

affluent to support the profitable operation of services. This narrows the set of

airports that might be included in the product market, to include only those

airports that provide access to a relatively large pool of demand, as an airline