Overdose Prevention in New York City:

Supervised Injection as a Strategy to

Reduce Opioid Overdose and Public

Injection

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary 03

Background 07

Overdose in New York City

HealingNYC 12

Expanding New York City’s Response to the Overdose Crisis

A Legacy of Public Health Innovation in New York City 17

Why Supervised Injection Facilities? 20

A Review of the Evidence

Would New Yorkers Support Supervised Injection Facilities? 23

Community Support for and Concerns about Supervised Injection

What Would New York City Gain from Supervised Injection Facilities? 33

Estimating the Health and Fiscal Impacts of Supervised Injection in New York City

How Could New York City Implement Supervised Injection Facilities? 36

Viable Legal Frameworks for Supervised Injection Facilities in New York City

Case Studies: Supervised Injection Facilities at the Municipal Level 40

Update from Seattle, San Francisco, and Philadelphia

Recommendations 43

Acknowledgments 48

References 51

Appendix A 55

Institutional Support for Supervised Injection

Appendix B 57

Statement of Support for Supervised Injection from the American Medical Association

Appendix C 59

Statement of Support for Supervised Injection from the American Public Health

Association

2

Appendix D 81

Letter of Support for Supervised Injection from amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS

Research to New York State Governor Andrew M. Cuomo

Appendix E 83

New York City Supervised Injection Facility Impact Report

Appendix F 127

Legal Challenges to and Avenues for Supervised Injection Facility Implementation in

New York City

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Overdose deaths in New York City have risen steadily over the past 15 years, growing to

the crisis we now face. In 2017, provisional data confirmed 1,441 overdose fatalities in

New York City—the deadliest year on record.

1

Someone dies from a drug overdose in New

York City every seven hours, and more people died from overdose in New York City in 2017

than from suicide, homicide, and motor vehicle accidents combined.

2

Since 2014, fentanyl,

an opioid 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, has driven the dramatic increase in

overdose deaths.

The opioid overdose epidemic in New York City persists despite current efforts, which

include availability of treatment services, collaborative interventions between public

health and law enforcement, and increased access to the emergency overdose rescue

medicine naloxone. Recognizing that opioid-involved overdose deaths are preventable, the

City has redoubled its efforts with a broad, multi-agency cross-sector approach known as

HealingNYC. This comprehensive strategy aims to reduce opioid overdose deaths by 35%

by 2022. Key components of HealingNYC include: expanded access to effective treatment;

innovative methods of overdose prevention that reach individuals at high risk; education

aimed at clinicians and communities to prevent substance misuse before it starts; and

using new methods to reduce the supply of drugs.

3

As HealingNYC moves forward, the City

maintains its commitment to deploying strategies grounded in science and to considering

all evidence-based interventions that could prevent people from dying in the present

overdose crisis.

Supervised injection facilities (SIFs) are one public health strategy to reduce overdose

deaths, infectious disease transmission, and public drug use. Supervised injection facilities

offer hygienic spaces for people to inject drugs obtained offsite using sterile equipment

under medical supervision. There are 100 SIF locations worldwide, including a recent

expansion to three cities in Canada. In the United States, SIFs have not been implemented

but are under consideration in at least five cities. Through co-location or referral, SIFs also

provide people who inject drugs access to a range of health, substance use, and social

services. As such, SIFs serve as an early entry point along the continuum of care for people

with substance use disorders. Finally, SIFs have garnered support and endorsement from a

range of professional health bodies, including the American Medical Association,

4

the

American Public Health Association,

5

the International Drug Policy Consortium,

6

and the

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.

7

To explore the potential impact of incorporating supervised injection into City’s opioid

response strategy, the New York City Council provided funding to the New York City

Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) to assess the feasibility of establishing

a SIF. DOHMH began with a literature review to summarize the international experience

with SIFs. Additionally, an Expert Advisory Panel comprised of national and international

drug policy experts, scientists, and advocates was assembled to guide the study. A list of the

Expert Advisory Panel members can be found in the Acknowledgments.

4

To explore the feasibility of SIFs in New York City, three key questions were addressed:

1. Would New Yorkers support supervised injection facilities?

The New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM) and DOHMH conducted structured

focus groups and individual interviews regarding perspectives on supervised

injection services with key community and institutional stakeholders. Participants

represented a range of constituencies: law enforcement, health care, social and

community services, faith traditions, business development, and harm reduction.

Input from elected officials serving in New York City and State offices also was

solicited.

2. What are the potential health and fiscal benefits of a supervised

injection facility to New York City?

Researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College projected the impact of a supervised

injection facility on opioid overdose deaths and direct health care expenditures in

New York City, looking at emergency medical service usage, emergency department

visits, and hospitalizations. A Technical Advisory Group composed of global leaders

in supervised injection with expertise in economics, policy analysis, and clinical and

behavioral sciences offered guidance and oversight to this study.

3. What are the viable legal frameworks within which New York City could

establish a supervised injection facility?

A legal scholar from Columbia Law School assessed the current legal barriers to the

establishment of a supervised injection facility in New York City to identify potential

avenues for implementation. This review assessed federal, state, and municipal

criminal and civil laws and regulations that could be relevant to the establishment of

a SIF in New York City, as well as examples and lessons learned from other

jurisdictions across the United States. The findings from this review support the

feasibility of supervised injection facilities.

Supervised injection is an evidence-based health intervention for people who

inject drugs

Scientific evidence suggests that SIFs—like methadone maintenance treatment and syringe

exchange programs established in response to the previous opioid and HIV/AIDS crises—

prevent overdose and reduce the harms associated with injection drug use, including HIV

and hepatitis C transmission. Supervised injection facilities provide support and

connections to health and social services to marginalized individuals, particularly shelter

residents, so people who inject drugs can reduce their risk of death and take positive steps

toward healthier lives. In addition to the individual benefits, research from other

jurisdictions shows that SIFs may lead to long-term reductions in individual-level drug use

and community-level drug-related crime in areas where they are located, and thus save

taxpayer dollars on health care and crime control.

5

Key community leaders recognize the benefits of and challenges to establishing

supervised injection as a strategy to prevent overdose and reduce crime

Findings from NYAM’s community assessment and DOHMH’s stakeholder interviews

suggest that supervised injection facilities have the support of many medical, harm

reduction, business, faith, community, and elected leaders. Stakeholders acknowledged the

seriousness of the overdose crisis, the need for new solutions, and the functional approach

of SIFs. Stakeholders particularly appreciated SIFs’ role in linking participants to needed

medical, social, and community services. Some stakeholders highlighted potential

community concerns that SIFs could convey that drug use was being condoned or create

geographic concentrations of people who inject drugs. These community concerns could

lead to challenges with SIF placement, although these challenges may be mitigated through

co-location within existing harm reduction services as part of the continuum of care.

Almost all leaders and community representatives interviewed, however, acknowledged

the public health and safety benefits of supervised injection. Stakeholders emphasized that

meaningful community engagement and education would be critical to the success of SIFs,

particularly in any neighborhoods that could be selected for SIF placement. Additional

engagement is needed to best capture all community perspectives, as current findings are

limited to those who agreed to participate at the time of the study.

Establishment of four supervised injection facilities could conservatively avert

up to 130 overdoses and save up to $7 million in public health care costs

annually

Results from the impact study conducted by Weill Cornell Medical College found that

locating SIFs in four New York City neighborhoods most severely affected by fatal drug

overdose could prevent up to 130 overdose deaths each year and reduce associated annual

costs to the City health care system by up to $7 million. The estimates generated by this

study are conservative, as they do not include reduction in crime or chronic disease

treatment costs associated with injection drug use. The cost-savings of a SIF would be

offset by the costs to operate a SIF. These costs would vary depending on the model and

hours of operation. On the low end, a SIF could be implemented for $250,000 annually; on

the upper end, a new, freestanding facility with long hours could cost between $2 and $3

million.

Legal establishment of supervised injection facilities in New York City is possible

Findings from the legal review suggest that, despite legal barriers, state and municipal

options exist to establish one or more SIFs in New York City. Any avenue would require

engaging diverse representatives from public health, public safety, law enforcement,

advocacy and community groups, and elected officials in the planning process.

Taken together, these findings have led to a series of recommendations regarding the

planning and implementation of a SIF to supplement New York City’s comprehensive

overdose prevention strategy. In particular, the recommendations presented in this report

aim to leverage New York City’s existing treatment and social service resources to integrate

SIFs within established networks of care. A wide range of stakeholders in New York City

support supervised injection as a strategy, but also acknowledge potential community

6

concerns in establishing supervised injection services. Our recommendations around SIFs

build on the legacies of methadone maintenance treatment and early grassroots adoption

of syringe exchange programs by health advocates, medical and social service

professionals, and scientists in New York City. Additionally, New York City has a strong

network of health and social service agencies, and productive collaboration between the

public health and public safety communities—all essential partners to launch SIFs.

What follows are detailed findings from the three commissioned studies, supplementary

data collected by DOHMH, and a comprehensive review of the existing body of scientific

evidence on supervised injection. Overdose affects all New Yorkers. To learn more about

overdose prevention, we invite readers to visit: www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/health-

topics/alcohol-and-drug-use-prevent-overdose.page.

7

BACKGROUND

Overdose in New York City

The United States is in the midst of a overdose epidemic, with over 63,000 deaths in 2016

due to overdose. The majority of these deaths (66%) are caused by opioids, a drug class

that includes prescription painkillers, heroin, and the highly potent synthetic compound

fentanyl.

8

The entire nation—East and West, North and South, urban and rural—has been

touched by this crisis, which has shown no signs of slowing down.

Like the rest of the country, New York City has experienced alarming increases in overdose

deaths over the last 15 years. The number of deaths from overdose in New York City have

more than doubled since 2000, with an increase of over 2.5 fold since 2010. In 2017,

provisional data shows that 1,441 overdose fatalities ocurred in New York City, the highest

number ever recorded. Over 80% of these deaths involved opioids.

9

Someone dies every

seven hours of overdose in New York City; there are more annual deaths from opioid

overdose than from car crashes, suicides, and homicides combined.

10

Figure 1: Number of unintentional drug poisoning (overdose) deaths by year,

New York City, 2000 – 2017

Source: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Unintentional Drug Poisoning (Overdose) Deaths Quarters 1-4, 2017,

New York City, released April, 2018.

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

1600

Number of overdose

deaths

1,441 overdose deaths

deaths

8

Figure 2: Number of deaths from unintentional drug poisoning (overdose) compared to intentional self-harm

(suicide), assault (homicide), and motor vehicle crashes in New York City, 2006 – 2017

Source: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Unintentional Drug Poisoning (Overdose) Deaths Quarters 1-4, 2017,

New York City, released April, 2018.Li W, Sebek K, Huynh M, Castro A, Gurr D, Kelley D, Kennedy J, Maduro G, Lee E, Sun Y, Zheng P, and

Van Wye G. Summary of Vital Statistics, 2015. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Bureau of Vital

Statistics, 2017.

Zimmerman R, Li W, Gambatese M, Madsen A, Lasner-Frater L, Van Wye G, Kelley D , Kennedy J, Maduro G, Sun Y. Summary of Vital

Statistics, 2012. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Bureau of Vital Statistics, 2013.

Although prescription painkillers helped to drive the increase in the rate of overdose

deaths in New York City from 2010 to 2011, the proportion of overdose deaths involving

opioid analgesics had decreased to 18% by 2016, from a high of 35% in 2011.

11

Between

2011 and 2014, a rise in heroin-involved overdoses drove the increases in overdose deaths.

Beginning in 2015, New York City has experienced the emergence of fentanyl, which was

involved in nearly half (44%) of all overdose deaths by the end of 2016.

12

0

1000

2000

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Number of deaths

Deaths From Overdose

Deaths From Suicide, Homicide, and Motor Vehicle Crashes

1,441 overdose deaths

9

Fentanyl: A public health crisis

Fentanyl is a highly potent synthetic opioid propelling drug overdose deaths to

record numbers. While fentanyl is a prescription medication used for cancer-related

pain or palliative care, non-pharmaceutical fentanyl has been introduced into illicit

drug markets in New York City and nationally in recent years. Typically, fentanyl

found in the illicit drug supply typically is not sourced from diverted prescriptions,

but rather is produced in illicit laboratories and used as a common adulterant to

heroin, cocaine, and counterfeit pills—including opioid analgesics, such as

oxycodone, and benzodiazepines, such as Xanax. The presence of fentanyl in illicit

drugs puts people who use them at enormously increased risk of overdose.

13

Fentanyl’s potency is such that a small amount can induce overdose; as a fast-acting

opioid, overdoses involving fentanyl can occur within minutes of ingestion.

14

Toxicology analyses indicate that fentanyl drove the increase in overdose deaths

from 2015 to 2016. Deaths involving fentanyl have increased nearly every quarter

since 2015, constituting almost half (44%) of all overdose deaths in 2016.

15

The acceleration of overdose deaths since the introduction of non-pharmaceutical

fentanyl in the New York City drug supply has brought a mutual recognition among

the public health and safety communities that new and different strategies must be

considered.

Many people who inject drugs in New York City are aware of the risks of fentanyl

and generally do not seek it out.

16

Typically fentanyl is introduced into illicit drug

mixes at the level of the supplier. As a result, people who use drugs and street-level

drug sellers are unlikely to know whether a certain product does or does not

contain fentanyl.

17, 18

Additionally, other non-pharmaceutical fentanyl analogues

may not yet be identifiable by existing laboratory tests.

Figure 3: Number of drug overdose deaths and percent of overdose deaths involving fentanyl in New York

City, by quarter, 2014-2016

Source: Paone D, Nolan ML, Tuazon E, Blachman-Forshay J. Unintentional Drug Poisoning (Overdose) Deaths in New York City, 2000–

2016. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: Epi Data Brief (89); June 2017.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

0

100

200

300

400

2014 2015 2016

Percent fentanyl

Number of

overdose deaths

Number of overdose deaths

Percent of overdose deaths involving fentanyl

10

Overdose affects all neighborhoods in New York City and cuts across lines of race, class,

age, and gender. However, certain populations and neighborhoods bear a disproportionate

burden of overdose deaths. Residents of both poor neighborhoods with endemic heroin-

related issues and affluent neighborhoods with more recent heroin- and fentanyl-related

issues experience some of the highest rates of opioid-involved overdose citywide. In 2016,

Staten Island and the Bronx experienced the highest rates of fatal overdose in New York

City in 2016 (31.8 and 28.1 per 100,000 residents, respectively), over two times higher

than residents of other boroughs. The largest numbers of deaths in 2016 occurred among

residents of the Bronx and Brooklyn, with 308 and 297 deaths, respectively. The breadth of

harm spans East Harlem in Manhattan, Hunts Point-Mott Haven in the Bronx, and South

Beach-Tottenville in Staten Island, as well as neighborhoods in other boroughs.

19

Taken

together, these numbers illustrate the widespread but unequal burden across the city.

Figure 4: Top five New York City neighborhoods: Rates of unintentional drug poisoning (overdose) involving

heroin and/or fentanyl by neighborhood of residence, 2016

Source: Paone D, Nolan ML, Tuazon E, Blachman-Forshay J. Unintentional Drug Poisoning (Overdose) Deaths in New York City, 2000–

2016. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: Epi Data Brief (89); June 2017.

Overdose death rates have increased dramatically among all racial groups from 2015 to

2016. In 2016, white New Yorkers experienced the highest rate (18.9 per 100,000) of

heroin- and/or fentanyl-related overdose death citywide, followed by Latino/a New

Yorkers (16.9 per 100,000); the rate among black New Yorkers was 12.3 per 100,000.

Rate of overdose deaths involving

heroin and/or fentanyl, 2016

0.0

10.0

20.0

30.0

(per 100,000 residents)

11

Although males experience rates of overdose from heroin and/or fentanyl over four times

that of females, both male and female New Yorkers experienced substantial fentanyl-driven

increases from 2015 to 2016.

Individuals who reside in shelters or are undomiciled are at increased risk of overdose.

These individuals represented 7% of the overdose deaths in New York City in 2016, despite

comprising less than 1% of the City population.

20

Overdose is now the leading cause of

death for this population, overtaking heart disease in FY 2014.

21

Furthermore, people who

inject drugs in public or semi-public locations, many of whom are homeless or unstably

housed, are at heightened risk of infectious disease transmission (HIV and hepatitis C) and

other harms associated with injection drug use.

22

,

23

2015 2016

White and Black race categories exclude Latino ethnicity.

Latino includes Hispanic or Latino of any race.

*Data for 2015 and 2016 are provisional and subject to change.

Source: Paone D, Nolan ML, Tuazon E, Blachman-Forshay J. Unintentional Drug Poisoning (Overdose) Deaths in New York City,

2000–2016. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: Epi Data Brief (89); June 2017

Number of overdose deaths

Figure 5: Increase in number of unintentional drug poisoning (overdose) deaths involving

heroin and/or fentanyl, by race/ethnicity, from 2015 to 2016*, New York City

9

.

Black

Latino

White

100

200

300

400

95

206

416

274

211

319

12

HealingNYC

Expanding New York City’s Response to the Overdose Crisis

In recent years, New York City has established itself as a national leader in addressing the

overdose epidemic through public health and public safety interventions. In March 2017,

the City committed an additional $38 million annually over five years to fight overdose

through HealingNYC, an innovative, multi-pronged agenda focused on four areas. In March

2018, the City expanded HealingNYC by an additional $22 million annually.

24

1. Prevent opioid overdose deaths

2009: DOHMH began to provide naloxone—a medication used to reverse the effects of an

opioid overdose—to syringe exchange programs and other registered opioid overdose

prevention programs for distribution to laypeople to carry and respond to overdose.

2013: The New York City Police Department (NYPD) equipped approximately 1,000 patrol

officers in the precincts with the highest rates of opioid-involved overdose with naloxone.

2014: The New York City Fire Department (FDNY) equipped emergency medical

technicians and certified first responder firefighters with naloxone. FDNY reported using

naloxone to reverse over 180 overdoses per month in the second half of 2016.

2014: Correctional Health Services, a division of New York City Health + Hospitals (H+H),

established one of the first jail-based naloxone distribution programs at the Rikers Island

Visitor Center. As of September 30, 2017, the program has distributed over 6,000 kits to

the families and friends of incarcerated persons, who are at elevated risk of overdose

following release from jail.

2015: The New York City Commissioner of Health authorized naloxone distribution by

pharmacists under a non-patient specific prescription (standing order), and the medication

is now available to laypeople without a personal prescription in over 725 pharmacies

citywide. Naloxone is now effectively available over the counter.

2016: The New York City Department of Social Services (DSS) trained all its shelter

providers in naloxone administration to ensure 24/7 overdose prevention coverage in the

City shelter system.

As part of HealingNYC, New York City committed to:

Distribute 65,000 naloxone kits in 100 services citywide, including, but not limited

to: treatment, detoxification, harm reduction, and other programs serving at-risk

New Yorkers and their families and loved ones

Equip all 23,000 NYPD patrol officers with naloxone and train all officers in

overdose response

13

Distribute 5,000 naloxone kits annually through the Rikers Island Visitor Center

program to directly target those individuals at increased risk

Increase the number of pharmacies offering naloxone without a prescription to

1,000

Distribute 6,500 kits in City shelters and continue to train Department of Social

Services shelter providers in naloxone administration

2. Prevent opioid misuse and addiction

2011: DOHMH developed New York City’s judicious opioid prescribing guidelines, which

served as the model for the guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention in March 2016. DOHMH’s guidelines subsequently were implemented in public

hospital emergency departments and private hospitals throughout the city.

2013: DOHMH employed public health detailing methods—delivering judicious

prescribing, overdose prevention, and door-to-door treatment messaging to health care

providers—to reach nearly 900 health care providers on Staten Island.

2015-2017: DOHMH expanded its door-to-door health care provider detailing efforts to

over 1,000 providers in the Bronx and nearly 1,000 providers in Brooklyn.

2016-2017: The City ran the “I Am Living Proof,” “Save a Life, Carry Naloxone,” and “I Saved

a Life” public awareness campaigns, its largest drug treatment and overdose prevention

public education campaigns to date.

2017: DOHMH launched Relay, a peer-based crisis intervention and overose prevention

service for individuals in emergency rooms following a nonfatal overdose event. At the

time of HealingNYC’s launch, the program was operational in four hospitals across the city.

As part of HealingNYC, New York City committed to:

Create mental health clinics in high-need schools to address youth substance use

and intervene early to prevent misuse and addiction before it starts

Deliver targeted prevention and treatment messaging in primary care settings to

communities at high risk of overdose

Train 1,500 clinicians annually in judicious opioid prescribing to reduce

overprescribing

Expand Relay to 15 emergency departments citywide

14

Public health detailing in New York City

Public health “detailing” campaigns deliver critical education and prevention

messaging directly to health care providers. Providers engage in one-on-one visits

with DOHMH representatives during which they receive educational messages

about the judicious prescription of opioid analgesic and benzodiazepine

medications and means to reduce patient risk of overdose. Judicious prescribing

messages recommend that prescribers utilize the lowest effective dose for the

shortest duration necessary to reduce the risk of overdose or other harms. Detailing

is a key component of the City’s prevention strategy, reaching providers to help

prevent substance misuse before it starts.

3. Connect New Yorkers to effective treatment

2007: Correctional Health Services, which operates the oldest jail-based methadone

maintenance treatment program in the nation (since 1987), first introduced

buprenorphine treatment to individuals detained at Rikers Island as part of a research

study. Rikers Island now offers access to both methadone and buprenorphine.

25

Like

methadone, buprenorphine is a medication that is highly effective in treating opioid use

disorder.

2016: DOHMH funded an innovative buprenorphine treatment model that supports nurse

care managers (NCM) in seven primary care organizations that run federally qualified

health centers. These NCM programs support primary care clinics and their clinicians to

provide comprehensive substance use care for patients with buprenorphine treatment.

As part of HealingNYC, New York City committed to:

Train an additional 1,500 health care providers in buprenorphine prescribing, with

a focus on engaging nurse practitioners and physician assistants, who are newly

eligible to prescribe buprenorphine under federal law

Expand the City’s nurse care manager for buprenorphine treatment model to

provide case management services and increased patient adherence to an additional

seven federally qualified health centers

Start addiction treatment and care management with buprenorphine prescribing in

all New York City H+H primary care clinics

Establish buprenorphine induction, the first phase of maintenance, in at least 10

New York City emergency departments

Embed buprenorphine maintenance treatment in up to seven harm reduction

programs

Transform the New York City H+H substance use care network into a system of

excellence in addressing harmful opioid use

15

Increase the daily number of patients in the New York City jail system receiving

methadone to 600 and buprenorphine to 150, and offer individualized treatment

plans and connections to care for these patients upon release

Engage health professional training programs and health systems leadership to

cultivate workforce readiness and optimize responses to treatment needs

Connect New Yorkers involved with the criminal justice system to substance use

services through the HOPE (Heroin Overdose Prevention and Education) Program

Connect New Yorkers with substance use and mental health problems to necessary

treatment services through by establishing Health Engagement and Assessment

Teams (HEAT)

4. Reduce the supply of dangerous opioids

2012: DOHMH and the New York/New Jersey High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area

launched New York City RxStat, a public health and safety working group comprised of

over 25 City, State, and federal agencies that share information about overdose and

strategize collaborative policies and interventions to reduce overdose death. RxStat has

been hailed as a leading national model by Former President Obama’s White House Office

of National Drug Control Policy and the United States Department of Justice.

2015: NYPD increased heroin seizures by 32% citywide.

2016: NYPD and the Staten Island District Attorney’s Office launched the Overdose

Response Initiative to investigate overdose deaths to rapidly identify dealers, dismantle

distribution operations, and provide assistance to families and friends of overdose victims.

As part of HealingNYC, NYC committed to:

Increase laboratory and technology capacity at the NYPD and Office of the Chief

Medical Examiner narcotics testing labs to identify new dangerous synthetic drugs

and target supply reduction operations

Expand the Overdose Response Initiative to more neighborhoods

Add NYPD personnel to New York City airports, highways, and ports to disrupt the

opioid supply at the level of trafficking

16

The continuum of care for people who use drugs

The identification, diagnosis, care, and treatment of substance misuse and substance

use disorders are part of a range of services available to people who use drugs.

Termed the continuum of care, these services span multiple health care settings,

from specific programs for substance use, like overdose prevention programs and

opioid treatment programs, to medical settings such as hospitals, emergency care,

and primary care that address individuals’ general health needs. Providing a range

of services with complementary goals and capabilities allows people who use drugs

to enter this continuum and receive care that matches their needs.

Primary care, emergency medical systems, and hospitals can effectively leverage their

high volumes of patient contact to identify substance use disorders and initiate

treatment—particularly medication for addiction treatment—among patients at

risk of overdose or other negative health outcomes. Practitioners in these settings

can treat the complications of substance use disorders and provide connections and

referrals to other parts of the continuum of care that would meet an individual

patient’s needs.

Treatment for opioid use disorder is most effective when it includes the use of

medication, termed medications for addiction treatment (MATs). The best-studied

medications are methadone and buprenorphine. Both medications have been shown

to decrease the risk of death from overdose and increase the likelihood of

individuals reducing or ceasing their drug use and improving their social and

economic lives. These medications can be used as long-term treatment depending

on individual need. Medications for addiction treatment also reduce the risk of

HIV/AIDS, chronic hepatitis C infection, other health problems, and even

engagement in criminal activity.

Harm reduction programs provide services and programing for people who use and

inject drugs. These programs may include but are not limited to syringe exchange

programs, support groups, and treatment services. Harm reduction programs aim to

serve people who use drugs by providing connections to support services, such as

housing, public benefits, education, or workforce programs.

Supervised injection facilities provide a space for people who use and inject drugs to

do so safely, in private settings with medical staff who can readily respond to an

overdose. SIFs reduce other risks associated with injection, such as bloodborne

disease transmission, and alleviate the threat of arrest and incarceration. On-site

medical, substance use treatment, and social services allow individuals to receive an

appropriate level of support.

17

A Legacy of Public Health Innovation

in New York City

The current opioid overdose epidemic is not the first drug-driven health epidemic to

necessitate an innovative public health response in New York City. New Yorkers have a

recognized history of national leadership in responding to substance use and associated

harms with scientifically grounded innovative approaches that protect public health.

1960s and 1970s

New York City experienced its first large-scale increase in injection heroin use in the

decades following World War II. By the 1960s, heroin-involved overdose was the leading

cause of death among New Yorkers between the ages of 15 and 35, with 75% of deaths in

this age group attributed to heroin overdose.

26

In response, the world’s first methadone

maintenance treatment program (MMTP) was established as a research pilot at Rockefeller

University in 1964. Methadone is a medication that prevents withdrawal symptoms and

reduces cravings for people with opioid use disorder. This groundbreaking pilot

demonstrated the efficacy and safety of methadone as a long-term maintenance therapy.

Over the next decade, MMTPs were institutionalized across the New York City health care

system and prescribed to approximately 34,000 patients. Scientific evidence and rigorous

evaluations indicating MMTPs’ association with decreases in overdose, drug-related crime,

and hepatitis transmission helped to push forward public and governmental acceptance

and propel the treatment toward wider use.

27

By the close of the 1970s, the heroin

overdose epidemic declined in large part due to the expansion of methadone maintenance

treatment.

28

While methadone maintenance is now widely accepted as the standard of care

for treating opioid use disorder, the intervention initially faced significant opposition.

However, the combined efforts of scientists, health care professionals, advocates, and

government led to the program that exists today. Approximately 30,000 people are

currently enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment in New York City.

1980s and 1990s

The second drug-driven epidemic New York City faced was the catastrophic rise of

HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and early 1990s. By 1984, an estimated 100,000 people who

injected drugs were infected with HIV in New York City, the highest disease concentration

among people who injected drugs in the United States.

29

Without access to sterile syringes,

HIV was spreading and people were dying at alarming rates, as sharing injection equipment

and paraphernalia greatly increases the risk of bloodborne disease transmission.

Advocates and health researchers identified lack of access to sterile syringes as a risk factor

in disease transmission and advocated for increased access to sterile syringes.

This collaboration resulted in the founding of syringe exchange programs (SEPs), now an

accepted public health intervention despite initially vehement opposition in the 1980s.

Opponents charged that syringe exchange programs condoned drug use and would lead to

increased drug use and crime in communities. However, evaluations of SEPs in Europe

18

indicated the contrary: SEPs led to reductions in community drug use and crime and, most

importantly, reductions in HIV transmission.

30

,

31

Despite the strength of this scientific

evidence, governmental opposition to syringe exchange continued in the United States.

Health advocates, unable to obtain licensure or approval to open a formalized service,

distributed syringes underground to quell the HIV epidemic.

32

By the early 1990s, the scientific evidence was overwhelming that syringe exchange

reduced HIV transmission. Proven effectiveness along with the mounting toll of AIDS,

which took so many lives, spurred government to action. In May 1992, after a decade of

advocacy by scientists and activists,

33

the New York State Department of Health adopted

emergency regulations to authorize the possession and distribution of syringes without a

prescription. This emergency regulation was adopted into law in October 1993, and the

first formal and legal syringe exchange pilot began in New York City, supported by a grant

from the Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). An evaluation confirmed the pilot’s

effectiveness in reducing risk behavior and HIV infection, with no documented increases in

injection drug use or negative impacts at the community level.

34

As evidence of the health

benefits of SEPs in New York City grew, more sites opened across the city and the scope of

SEPs expanded to offer a broad range of essential services, such as on-site medical care,

substance use treatment, and housing placements. By the late 1990s, these programs were

attributed with driving down the prevalence of HIV infection among people who inject

drugs, and further, reducing HIV transmission to sexual partners.

35

This momentum has

continued; in 2001 New York State implemented the expanded syringe access program to

make syringes available without a prescription in pharmacies and medical settings

statewide. Syringe exchange programs remain a significant contibutor to the overall

reduction in HIV cases in New York City.

36

Although syringe exchange has become institutionalized in New York City, the intervention

remains contested in some jurisdictions across the United States and to date remains illegal

in 23 states. Indiana—one state where syringe exchange is illegal—experienced an

outbreak of HIV infections in 2015 in rural communities of people who inject drugs.

Researchers quickly linked the outbreak directly to unsafe and unhygienic injection

practices. Deeply held opposition to syringe exchange among Indiana government officials

and national coverage of the outbreak reopened a public debate about the intervention.

Proponents urged state leaders to lift the ban on syringe exchange. Opponents eventually

permitted the practice temporarily on an emergency order from the governor. In the year

between detection of the outbreak and the opening of syringe exchange, nearly 200

individuals in Scott County tested positive for HIV, compared with only five HIV diagnoses

in the county between 2004 and 2013. Following the implementation of syringe exchange

in the affected counties, the pace of infection slowed and the outbreak was contained.

37

2000s and 2010s

The current opioid epidemic in the United States began more than 15 years ago, driven by

the aggressive marketing of opioid analgesic medications by the pharmaceutical industry.

The epidemic has escalated since 2010, particularly due to demand for heroin and more

recently the introduction of fentanyl into the illicit drug supply. As a result of fentanyl, drug

19

overdose deaths are at unprecedented levels nationally and in New York City. While new

health and safety resources have been devoted to overdose prevention at the local, state,

and federal levels, the sheer magnitude of this epidemic has compelled scientists, health

experts, professional societies, and advocates in the United States to reassess how to

address substance use. Among the range of additional strategies under discussion are SIFs,

which have been shown to reduce overdose deaths in people who are most vulnerable,

including people who are unstably housed.

38

Supervised injection facilities were established in Europe in 1992. This model has been

adopted widely in Europe—initially in Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands—as

well as more recently in Australia and Canada. Supervised injection facilities now operate

in more than 10 countries. Abundant scientific evidence supports the effectiveness of SIFs

to reduce deaths and other health consequences of injection drug use while facilitating

access to the continuum of care. At the same time, the data refutes concerns that SIFs

would cause increases in drug use or crime. Based on this information, many advocates and

professional health bodies publicly support the establishment of SIFs and ask that local and

state governments implement this strategy as a lifesaving measure. In response, legislation,

new policy, or studies are in progress in Colorado, Maryland, Maine, Massachusetts, New

York City and Ithaca, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Seattle.

20

WHY SUPERVISED INJECTION

FACILITIES?

A Review of the Evidence

Supervised injection facilities are one of many overdose prevention strategies available to

public heath authorities. They have been shown to improve individual and community

health, increase public safety, and reduce the health and social consequences of injection

drug use through medically supervised use of injected substances. Supervised injection

facilities offer hygienic spaces where people who inject drugs can inject pre-obtained

substances with sterile equipment. Medically trained staff are on-site to respond to

potential overdose events, although these staff do not assist with injection. Most

established SIFs refer or provide access to a host of on-site health, mental health, substance

use, and social services that supplement existing harm reduction and syringe exchange

services through increased opportunities for engagement, education, and treatment.

Approximately 100 SIFs operate in 10 countries and 67 cities worldwide, with six

additional facilities scheduled to open across Europe and Canada over the next two years.

39

Although no SIFs exist in the United States, a number of jurisdictions have announced

intentions to open or explore the possibility of opening these facilities, including Colorado,

Maryland, Maine, Massachusetts, Seattle, San Francisco, and Ithaca, New York.

A growing body of scientific evidence, generated primarily though evaluations of existing

facilities, suggests the safety and effectiveness of SIFs. To date, no fatal overdose has been

documented in a SIF anywhere in the world.

40

,

41

Supervised injection facilities reduce overdose mortality and associated harms

Community impact studies conducted in Vancouver, Canada, have found reductions in fatal

overdose of up to 35% in communities where SIFs are located.

42

Evaluations of a SIF in

Sydney, Australia, have demonstrated reductions of up to 80% in overdose-related

emergency medical service calls in areas surrounding SIFs.

43

The safe and “low-threshold”

*

access to safer injection, overdose prevention, health care, and drug treatment services

provided by SIFs are associated with decreases in risk-taking behavior among consistent

SIF visitors and reductions in the harms associated with public injection.

44

Supervised injection facilities improve access to health care and social services

People who use drugs may face stigma that can create barriers to accessing medical and

mental health care and social services.

45

By offering on-site medical services, SIFs increase

access to routine primary care for people who inject drugs and facilitates linkages to

ancillary services.

46

,

47

Evaluation of Vancouver’s SIF found that on-site and referred

*

That is, minimal barriers to entry, free, and with few or no demands on the individual in exchange for the

service.

21

medical services provided to SIF visitors reduced the length of their hospital stays and

improved overall health.

48

Supervised injection facilities reduce injection-related health risks

By providing sterile injection equipment and a safe space to inject, SIFs can further reduce

transmission of bloodborne infections, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV). Conservative

estimates from Vancouver suggest that a single SIF can prevent up to 35 new cases of HIV

per year.

49

,

50

Supervised injection facilities also have been shown to reduce bacterial

infections associated with non-sterile injection equipment.

51

Supervised injection facilities,

as well as syringe exchange programs, educate clients about safer injection techniques and

proper syringe disposal, which disseminate through networks of people who inject drugs

and can lead to increased community use of safe and hygiene techniques.

52

Research

indicates that individuals who inject in public or semi-public locations are at heightened

risk of injection-related health complications since their injection is often rushed out of fear

of being sighted, interrupted or arrested. Rushed injections increase risks of using non-

sterile equipment, developing and spreading infections, and overdosing. As the majority of

individuals who inject publicly are homeless or unstably housed,

53

,

54

SIFs are particularly

well-suited to meet the needs of this high-risk and underserved population.

Supervised injection facilities increase referrals to drug treatment

Supervised injection facilities, like other harm reduction services, have been shown to

increase referrals to and uptake of drug treatment and detoxification and, over time, are

associated with drug use cessation.

55

-

57

These findings serve as an important reminder that

SIFs, harm reduction, and treatment are all points along a continuum of care for people

who use drugs.

Supervised injection facilities provide outreach, engagement, and care to

marginalized populations

Supervised injection facilities function as spaces to engage and connect marginalized or

disconnected populations with health care, harm reduction, and other social services.

Research has demonstrated that SIFs may function as safe havens for women who inject

drugs, thereby reducing violence against women associated with street-based drug use.

58

Similar findings have shown increased engagement with homeless or unstably housed

young adults, a group at elevated risk of overdose and infectious disease transmission.

59

Supervised injection facilities reduce health care expenditures

Evaluations of SIF sites worldwide have demonstrated annual savings of up to $3.5 million

per site in averted HIV and HCV treatment costs.

60

Other estimates suggest savings of up to

$18 million over a 10-year period based on the number of averted overdose deaths.

61

Supervised injection facilities do not increase crime or drug use

A number of studies, reviewed below, have examined whether SIFs have negative effects on

communities, including increased crime, drug use, or concentrations of people who use

drugs in the neighborhood in which a SIF is located. The potential for SIFs to have negative

effects on communities is one of the most frequent concerns raised.

22

Some opponents of supervised injection have suggested that SIFs increase drug-related

crime in areas where they are located. While this may seem like an intuitive conclusion

given that drug use remains illegal in the United States, research from Vancouver, Canada,

observed decreases in a range of drug-related crimes following the establishment of a SIF,

including decreases in drug sales, drug solicitations, and public injection.

62

Research from

Sydney, Australia, demonstated decreases in public perception of public injection,

discarded syringes, and drug-related crime.

63

Other studies evaluating the effects of SIFs on

their surrounding communities in Sydney have shown declines in vehicle break-ins and

auto theft and neutral effects on levels of drug trafficking, assault, or robbery in

communities with SIFs.

64

,

65

Opponents of SIFs have also suggested that these services promote drug use and

discourage treatment. However, evidence from Vancouver, Canada, suggests that SIFs

reduce drug use in neighborhoods where they are located, by providing engagement and

connections to harm reduction and drug treatment services.

66

SIFs can serve as an entry

point into the continuum of care and lead to reductions in drug use and drug-related health

and social consequences.

67

As reported above, SIFs increase participation in drug

treatment and are associated with long-term drug use cessation.

68

,

69

Additionally, some opponents of supervised injection facilities have suggested that these

services may facilitate initiation into substance use or substance use injection, particularly

among youth. Like syringe exchange programs, most SIFs are not accessible to individuals

under age 18. Research has shown, however, that the majority of SIF clients are long-term

injectors, with an estimated average injecting history of 16 years.

70

Additionally, SIFs

reduce the number of publicly-discarded syringes in communities where they are located

and thus reduce community exposure to injection drug use.

71

,

72

This reduced community

exposure to drug use can function as a prevention measure, particularly as SIFs are often

situated in areas with high concentrations of public drug use, drug-related activity, and

crime.

Opponents of SIFs have expressed concerns that these services may draw large numbers of

people who use drugs into communities where they don’t live. However, research has

shown that the majority of individuals who use SIF services are not likely to travel more

than 20 minutes to a given facility.

73

-

76

Existing SIFs have been located in areas with high

densities of drug use and overdose and function as a targeted health intervention for these

communities. Furthermore, this same concern arose in reaction to the early

implementation of syringe exchange programs and was disproved through evaluation of

SEPs.

23

WOULD NEW YORKERS SUPPORT

SUPERVISED INJECTION FACILTIES?

Community Support for and Concerns about Supervised

Injection

To assess the opinions of key stakeholders regarding the feasibility of opening a supervised

injection facility in New York City, the New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM) and the

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) jointly conducted a

community assessment. The assessment included focus groups and interviews with a range

of key stakeholders across the city. Findings are limited to those who agreed to participate

in the focus groups and interviews; several key stakeholders who have been vocal critics of

supervised injection were unavailable at the time of the study. Additional engagement is

need to best capture all community perspectives. An Expert Advisory Panel comprised of

national and international experts in supervised injection—including leading

epidemiologic and economic researchers, experts in drug policy and law, and advocates—

drew on research and implementation exertise to help identify stakeholder groups and

provide input into the study design and interview materials. A list of Expert Advisory Panel

members can be found in the Acknowledgments.

The assessment occurred in two parts. First, focus groups were conducted with a total of 52

people who use drugs to investigate if and how a SIF could meet the needs of this unique

and at-risk population in New York City. These focus group participants were asked about

their willingness to use a SIF, preferences regarding the types of services offered,

suggestions about the operational components of a facility, and perceived benefits and

concerns about SIFs.

Second, focus groups and individual interviews were conducted with a range of

stakeholders across New York City, including:

Elected officials

Law enforcement officials

Health care providers

Community leaders

Faith leaders

Business community representatives

Harm reduction program staff and management

The interviews and focus groups with the above stakeholder groups—which captured the

perspectives of 71 individuals separate from the sample of people who use drugs—aimed

to solicit opinions regarding community need for supervised injection services, gather

concerns about possible health or safety consequences that may be associated with a SIF,

and identify operational components of a SIF that communities consider essential.

24

Findings from both sets of focus groups and interviews are presented below.

People who use drugs: Perspectives on supervised injection

Between December 2016 and March 2017, researchers from NYAM conducted six focus

groups with a total of 52 people who use drugs. Participants were recruited from harm

reduction programs in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Manhattan. Researchers obtained

informed consent from all individuals prior to participation. Focus groups were conducted

anonymously and confidentially; no identifying information was obtained. Focus groups

were audio-recorded and fully transcribed for analysis. Participants received a $25

honorarium for their time.

At the beginning of each focus group, participants completed a short written demographic

questionnaire—the results of which are presented in Figure 6. Following the demographic

survey, researchers provided an overview of SIFs, including photographs and/or videos of

existing facilities to demonstrate what SIFs look like in practice. Researchers utilized an

open-ended interview schedule to guide the remainder of the focus group. Interviews

broadly probed: participant perceptions on supervised injection facilities, including

individuals’ willingness to attend or consider attending such a facility; operational aspects

of supervised injection facilities, including facilitators and barriers to access; and perceived

benefits and concerns about SIFs that might affect people who use drugs.

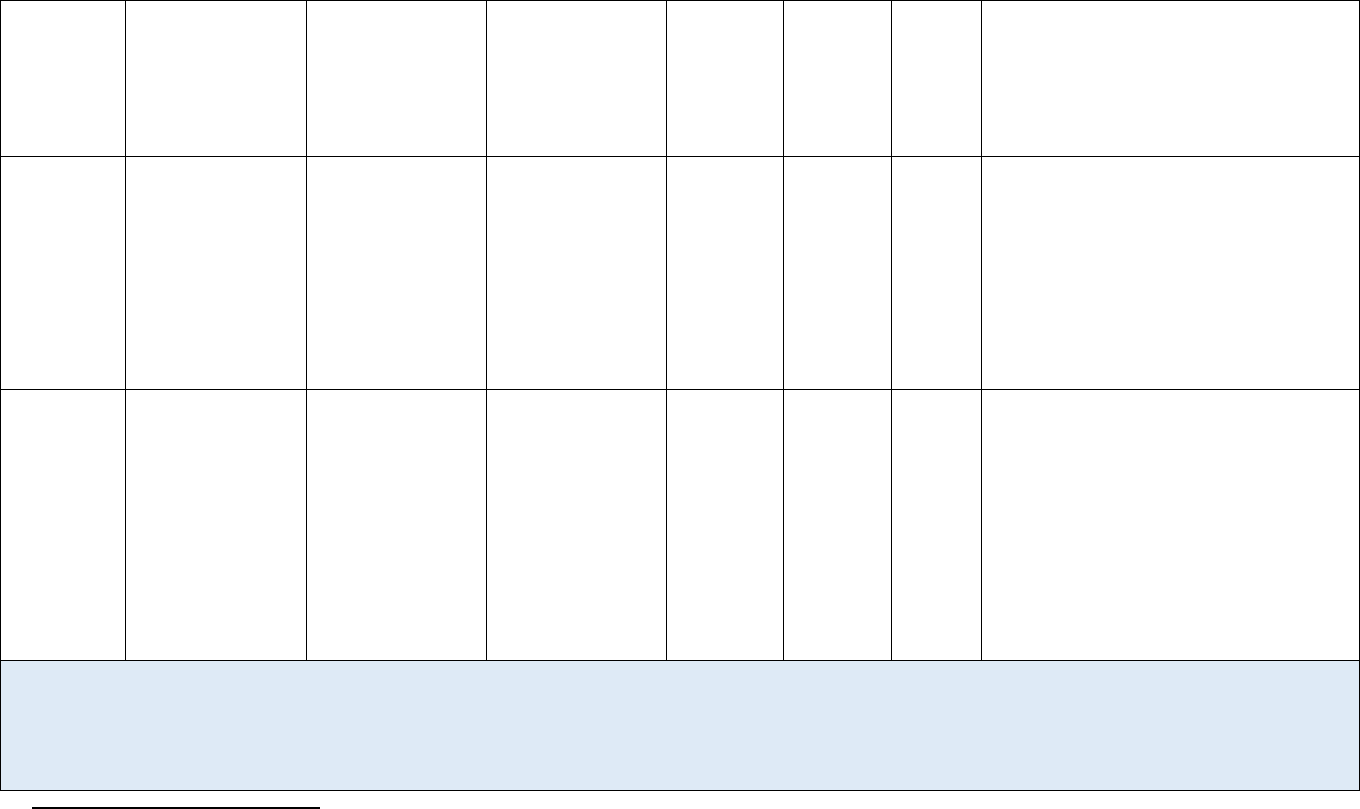

Figure 6: People who use drugs, demographic characteristics (n=52)

Total

52

100%

Age

18-30

8

15%

31-40

14

27%

41-50

19

37%

51-60

8

15%

60 & older

3

6%

Gender

Male

35

67%

Female

15

29%

Transgender

1

2%

Gender non-conforming

1

2%

Race/Ethnicity

White

11

21%

Black/African American

7

14%

Latino/a

22

42%

Multi-racial

10

19%

Other

2

4%

Housing status

Own home

14

27%

Other’s home

13

25%

Unstably housed

*

17

33%

Street homeless

8

15%

*

Could include: shelter, single room occupancy (SRO) facility, drug treatment facilty, supportive/transitional/three-quarter housing, or

hospital

25

Figure 7: Supervised injection facility, Vancouver, Canada

Photo courtesy New York Academy of Medicine

Three themes emerged during analysis of the focus group data: health and safety benefits;

site design and service integration; and community stigma.

Health and safety benefits

A number of participants discussed the fear they experience while injecting in public: fears

of being seen, interrupted, or arrested; and notably the fear of death due to injection alone

or in a clandestine location. Many participants considered supervised injection a viable

means of alleviating that fear.

“You have staff there that’s going to look out for you and make sure that you don’t overdose.

In your own car, you can overdose and nobody is there.”

—Person who uses drugs

Participants also described SIFs as potential safe spaces for people at risk of victimization,

including women and homeless people. This function of SIFs was of particular importance,

as some participants had experienced victimization as a result of high-risk public use. The

covert nature of public injection demands that individuals rush the injection process, which

can lead to injury or further harm. Participants perceived supervised injection facilities as

one means to prevent rushed injection.

“I think supervised injection is excellent for people that are homeless don’t have nowhere to

go. They’re constantly going to bathrooms and going, you know, places where they’re not

welcome. People don’t make them welcome. People barging in, and sometimes it’ll hurt. There

are injuries to your arm or something.”

—Person who uses drugs

26

Additionally, participants emphasized that, contrary to popular perception, people who use

drugs care very much about their health and share information regarding health issues

within their drug-using social networks. Many participants framed SIFs as a means of

bringing together a community striving toward health.

“It gets very macabre and lonely to be alone and shooting up, drinking. . . Having a place to go

where there's others around me, it could be uplifting and not only save my life if I were to

overdose, but save my life in other ways.”

—Person who uses drugs

Service integration and site design

Participants overwhelmingly emphasized the need for any supervised injection facility to

offer on-site or linkages to health care and supportive social services. Noting that SIFs

would target people who inject drugs publicly, participants—many of whom were street

homeless or precariously sheltered—described access to housing and basic medical and

psychiatric services as a critical component of a SIF.

“Safe injection, safe needles, doctors, psychiatrists, case workers, housing. The SIF has to

incorporate those in, you know, to make things work.”

—Person who uses drugs

Regarding site design, participants discussed a need for consistent operational hours to

engage and build rapport with clients as well as encourage regular service use. Early

morning operating hours were presented as necessary to facilitate withdrawal

management for people who use opioids. Late night hours were suggested as preventive

safeguards against sexual assault and other forms of violence—particularly violence

against women—that may more likely occur at night.

77

“Being a female, I would personally prefer something with middle of the night hours, that

would be the ultimate safe place for me. I don’t know how strong it is what I’m using. I don’t

know how my body is going to react to that particular shot. I really would like to be

somewhere totally safe, specifically within the you know timeframe of like, you know, 12 to

five, 12 to four. “

—Person who uses drugs

Community stigma and resistance

Most participants anticipated opposition to supervised injection facilities within their

communities, with many individuals linking this perceived opposition to pervasive stigma

against people who use drugs. Most participants recounted personal experiences of stigma

associated with their drug use from family members, medical providers, community

members, or even strangers. The stigma these marginalized individuals described led them

to a reflexive assumption that the community would be opposed.

“Stigma is life. Stigma is real. We stigmatize each other and we don’t even realize it. And

that’s a shame, because we get enough from society, you know what I’m saying. We really

27

need to be very mindful about the words that we use and the way that we refer to somebody

who is just as human as the next person. Whether I use or not is irrelevant.”

—Person who uses drugs

New York City stakeholders: Perspectives on supervised injection

Between January and December of 2017, six focus groups and 39 individual interviews

were conducted with a total of 71 stakeholders representing the following disciplines,

backgrounds, and interests: State and local elected officials; law enforcement officials;

health care providers specializing in psychiatry, primary care, emergency medicine,

correctional health, addiction medicine, infectious disease, and pharmacy; faith leaders

representing the Buddhist, Christian, Islamic, and Jewish traditions; business leaders and

small business owners; harm reduction program staff and management; and local

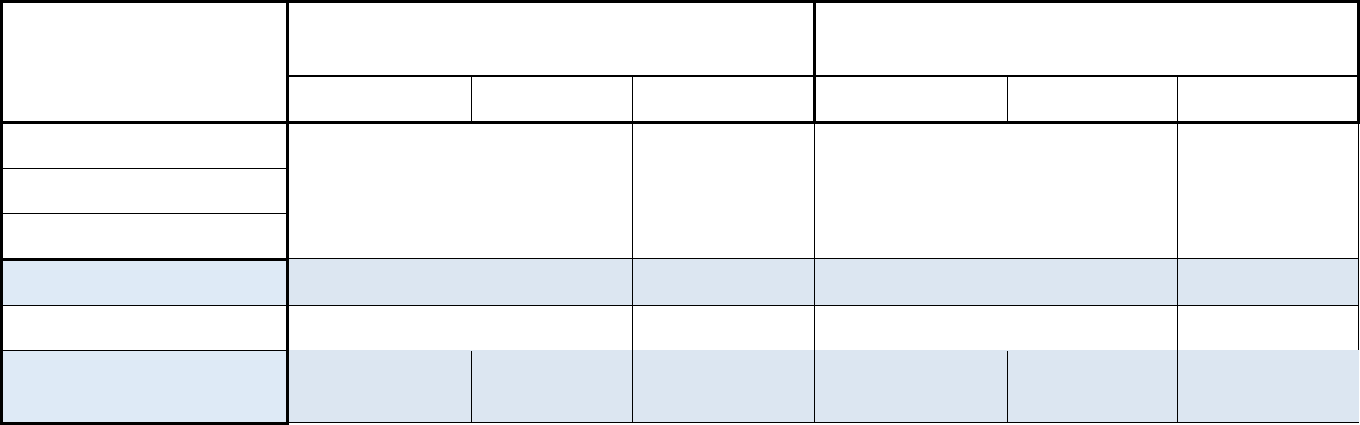

community leaders. A breakdown of stakeholders by category is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8: New York City stakeholders (n=71)

Business leaders and small business owners

8

Elected officials

8

Faith leaders

8

Harm reduction staff and management

23

Health care providers

7

Law enforcement officials

7

Local community leaders

10

Stakeholders were solicited for interviews by representatives from DOHMH and/or NYAM,

and all interviewees were assured of both organizational and personal confidentiality.

Focus groups and interviews were conducted using a structured interview guide that

probed perceived benefits and harms to communities and individuals that may result from

SIFs, as well as opinions on what features or services would be crucial to include in a

potential SIF. Consistent with the interviews with people who use drugs, at the start of the

interviews stakeholders were presented with background information about SIFs, which

included a fact sheet with results from studies and evaluations of SIFs worldwide and

photographs and/or videos of existing facilities. Audio recording was used at the

researchers’ discretion. At every interview, a designated scribe took detailed notes.

Demographic information was not collected at stakeholder interviews, and stakeholders

did not receive compensation.

28

Figure 9: Supervised injection facility, Sydney, Australia

Photo courtesy New York Academy of Medicine

Four themes emerged during analysis: health benefits; safety benefits; safety and

community concerns; and site design and community integration.

Health benefits

Across all stakeholders, there was broad agreement that reducing fatal overdose was a

critical need for their communities and New York City. Stakeholders generally

acknowledged the seriousness of the overdose crisis and the need for new solutions.

Regardless of whether stakeholders felt that SIFs were right for New York City, they nearly

all acknowledged that supervised injection is one evidence-based public health strategy

that could help avert overdose deaths.

“The idea of SIFs is creative but scary. A part of me says this is the wrong direction, but not

really, because there are so many people dying and in need.”

—Elected official

Some stakeholders—health care providers and harm reduction program staff, in

particular—viewed SIFs as an important step along the continuum of care for people who

use drugs and believed that engagement with these services could help individuals move

toward stability, health, and well-being. A number of health care providers considered SIFs

particularly important for individuals who might not be ready to fully curtail their drug use

and would otherwise be excluded from programs for which abstinence is a requirement.

Stakeholders who expressed this opinion generally viewed SIFs as an effective form of

overdose prevention and patient engagement—a way to keep people who use drugs alive

so that they may one day access treatment

29

“I think what people find the most challenging about caring for people who use drugs, is that

our [health care facility’s] model doesn't allow for continued drug use to be in care with us.

And so, we have to sometimes coerce or force a model onto a patient that isn't where they're

at in order for us to stay in a relationship.”

—Health care provider

Safety benefits

A number of stakeholders described a need for services that would reduce public injection

and publicly discarded syringes, which they viewed as hazards to public safety. Most

agreed that SIFs were one strategy to achieve these goals. The issue of community safety

was particularly salient among members of the business community, a number of whom

described some of the prior problems they had experienced with public injection and

public overdose in local places of business. These individuals were primarily interested in

whether SIFs would reduce high-risk drug use occurring in public and semi-public settings,

with many expressing the belief that moving public use into a private setting under medical

supervision would benefit both the community and the individual using the drugs.

“Often, a barista will be [at the café] by themselves at night, and [a person who injects drugs]

will use the bathroom, and then they'll sit down in the café and usually just be falling asleep or

nodding out. It's of concern because the staff isn't equipped to deal with that, and it's

upsetting to other customers, but it's also a concern to the person's health. I think that [a SIF]

is the best possible solution.”

—Small business owner

Some law enforcement officials viewed SIFs as potential cost-saving tools. When provided

with the evidence demonstrating localized decreases in both public drug use and

associated nuisance crimes following the establishment of a SIF, these stakeholders framed

the intervention in pragmatic, monetary terms. Even if they held reservations about

supervised injection, the possibility of reduced crime and criminal justice expenditures

functioned as a convincing argument for support.

“If SIFs give us less crime, less public drug use, and less vulnerability among drug users, police

will save enforcement resources. We need to enforce the law, but we also need to try things we

haven’t before.”

—Law enforcement official

“At the end of the day, it’s about serving the people. People who use drugs are real people with

real needs.”

—Elected official

Safety and community concerns

While concerns about SIFs were most frequently offered by law enforcement, all

stakeholders highlighted potential community concerns. First was the concern that

supervised injection could be perceived as condoning injection drug use, which remains

30

illegal in New York State. Some stakeholders framed the implementation of SIFs as

potentially negligent, given the increased overdose risks posed by fentanyl.

“I’m concerned that we’re arming people with the potential to kill themselves. The X factor is

what’s in the needle.”

—Law enforcement official

“We spend a lot of time trying to convince people that addiction is an illness. SIFs are almost a

bridge too far. It could have a terrible backlash.”

—Law enforcement official

Other stakeholders raised the concern that areas around a SIF might create new drug

markets in known locations and create geographic concentrations of people who inject

drugs. This perception could lead to challenges with SIF placement and generate pushback

from community members on the grounds that SIFs might bring new people who inject

drugs into their neighborhoods.

“Automatically you’ll have a fear issue. ‘Don’t you dare put that in my backyard.’ Needles?

They’ll say, ‘Oh my god, they’re bad people.’ Not that ‘people who use drugs are suffering.’”

—Local community leader

A handful of stakeholders raised the concern that their communities feel overburdened by

services for vulnerable populations and noted that community members were likely to

oppose a SIF on that basis. These stakeholders emphasized that their communities had

entrenched problems with regard to affordable housing, homelessness, workforce

development, and education that, for some individuals in their neighborhoods, might

supersede the needs of people who use drugs. Stakeholders emphasized that SIFs could

garner support in some communities by addressing some of these needs in addition to

offering overdose prevention and drug use services.

“It’s going to be hard to convince people that it works. We can’t even put supportive housing

in the neighborhood, because of the stigma surrounding the people who might occupy it.”

—Elected official

Some stakeholders, particularly more experienced elected officials and harm reduction

professionals, connected the current national debate about supervised injection with the

history of syringe exchange programs. These stakeholders recollected that similar concerns

were discussed widely in advance of the formal implementation of SEPs in the 1990s. They

noted that the political risk taken to implement SEPs ultimately benefitted the health and

safety of both individuals who use SEPs and their broader communities by reducing HIV

transmission.

“We don’t want to replicate the battle we fought about needle exchange. We need to educate

the public about the benefits: HIV reduction and overdose prevention.”

—Elected official

31

Site design and community integration

The majority of stakeholders suggested integrating supervised injection into established

harm reduction facilities rather than launching new facilities. They described a number of

perceived benefits of co-location within harm reduction programs: established credibility,

relationships, and trust with the surrounding communities and law enforcement; existing

on-site buprenorphine treatment services; existing on-site health and social services to

provide care and expedite and ease referrals; and existing expertise about injection drug

use and compassion for people who use drugs. Some stakeholders also suggested that

integration into harm reduction services could help assuage the concern that SIFs would

draw new people who use drugs to their neighborhood, as there is a substantial anticipated

overlap in use between syringe exchange and supervised injection.

“It’s a perfect idea to have the SIFs in the back and have the rest of the services out front.

Whatever people need they can just get.”

—Harm reduction professional

Stakeholders overwhelmingly agreed that a successful SIF ought to include co-located

health and social services. Individuals who are homeless and people who inject drugs in

public often are disconnected from health care, substance use treatment, housing, and

broader social services. Co-locating these services within SIFs would allow immediate

connections to be made. In particular, as SIFs sit at the early engagement end of the

continuum of care for people who use drugs, on-site or immediate access to drug treatment

services would allow individuals who feel ready to reduce or cease drug use to do so

immediately.

“We can’t just say over and over what a tragedy overdose is and do nothing about it. I like the

idea of a holistic approach to help people try to get better.”

—Law enforcement official

Nearly all stakeholders agreed that the success of a SIF was predicated on proactive

relationship-building between harm reduction program staff, medical providers, law

enforcement, and local community groups. This would involve preparatory outreach with

local police precincts to provide education on basic tenets of harm reduction and the

intended function and goals of the planned SIF. A successful model for this outreach exists

as part of the trust-building that has occurred between SEPs and local law enforcement.

Likewise, the SIF planning process must acknowledge, consider, and incorporate the needs

of police working with people who use drugs. A broad coalition of the stakeholders in this

assessment should be involved early in the planning and implementation processes for

establishing a SIF.

“I would welcome this in my district, but the community engagement piece is critical. You

need to start laying the groundwork now, because this will be contentious.”

—Elected official

32

“Are you going to find resistance? Yes. Are you going to need to educate? Absolutely. It will be

important to emphasize SIFs as one of many approaches to prevent overdose deaths.”

—Local community leader

33

WHAT WOULD NEW YORK CITY GAIN

FROM SUPERVISED INJECTION

FACILITIES?

Estimating the Health and Fiscal Impacts of Supervised

Injection in New York City

Weill Cornell Medical College conducted a study to estimate the overdose prevention and

public cost saving impacts of supervised injection in New York City. The study aimed to

develop neighborhood-specific estimates for overdose deaths prevented, given the wide

variation in mortality among different neighborhoods. Short-term cost savings estimates

were developed by identifying key areas of public health care expenditures that could

experience reductions from SIFs, including emergency medical services, emergency

departments, and inpatient hospitalizations. A brief review of the estimated impact is

presented below. Full text of the report prepared by Weill Cornell, including the methods

and results, can be found in Appendix B.

As part of the planning and execution of this impact analysis, a Technical Advisory Group of

five global experts in supervised injection provided guidance to Weill Cornell on methods,

analysis, and findings at key intervals across the life of the study between March and June

2017. Members of the Technical Advisory Group contributed a range of expertise across

economics, policy analysis, and the clinical and behavioral sciences. All members have

extensive experience in the evaluation of SIFs internationally.

To generate the the number of overdoses avoided, researchers developed a model that

accounted for the neighborhood-level number of death and the proportion of people who

inject drugs who are willing to travel to and use a SIF, drawn from the New York City

Injection Drug User Health Alliance Survey, 2013-2014 and 2014-2015. They used this