1

• Binding authority, also referred to as mandatory authority, refers to cases, statutes, or

regulations that a court must follow because they bind the court.

• Persuasive authority refers to cases, statutes, or regulations that the court may follow but

does not have to follow.

Binding versus Persuasive Authority: What’s the Difference?

WHICH COURT IS BINDING?

1

Binding vs. Persuasive Cases

© 2017 The Writing Center at GULC. All rights reserved.

You have found the perfect case: the facts are similar to yours and the law is on point.

But does the court before which you are practicing (or, in law school, the jurisdiction to which

you have been assigned) have to follow the case? Stare decisis is the common law principle that

requires courts to follow precedents set by other courts. Under stare decisis, courts are obliged

to follow some precedents, but not others. Because of the many layers of our federal system, it

can be difficult to figure out which decisions bind a given court. This handout is designed to

help you determine which decisions are mandatory and which are persuasive on the court before

which you are practicing.

To get started, ask yourself two questions:

1)

Are the legal issues in your case governed by state or federal law? and

2)

Which court are you in?

Once you know the answers to these questions, you are well on your way to determining

whether a decision is mandatory or persuasive.

Step 1: Are the Legal Issues in Your Case Governed by Federal or State Law?

First, a lawyer needs to know the facts and issues of the case. Facts such as where the

events took place, where the home(s) of the parties are, and where the parties conduct most of

their business frame the legal issues. In other words, identifying key facts will help you to

determine what law governs the legal issues in your case.

The hypothetical case below illustrates how you might analyze a particular set of facts to

identify whether the legal issues are governed by state or federal law. The first step is to identify

the facts and brainstorm all the possible legal issues raised by those facts.

1

By Robyn Painter and Kate Mayer. Revised in 2017 by Kate Mathews.

2

Hypothetical Case: Pick-Pocketing in Virginia

Facts

Possible Legal Issues

• You are shopping in a grocery store in

Virginia when a little old woman in line at

the checkout starts screaming that she’s

been pick-pocketed.

• The police arrive on the scene, and the

woman identifies you as someone who

suspiciously brushed against her.

• The police arrest you and throw you in jail.

• Later, the police interrogate you without

first informing you of your right to have a

lawyer present.

• Is pick-pocketing a crime in Virginia? If so,

under what law?

• Did the police have probable cause to arrest

you based on the identification of the old

woman?

• How reliable was the old lady’s

identification?

• How long can the police hold you?

• Were any of your Constitutional rights

violated during the police’s arrest and

interrogation of you?

• If you are found guilty, can the little old lady

also sue you in civil court for infliction of

emotional distress or another tort?

After you have brainstormed all the possible legal issues the facts raise, determine

whether the legal issues are governed by federal or state law. In any given case, there may be

both federal and state issues. America operates on a system of dual sovereignty: the fifty states

and the federal government all retain their own sovereignty. Because each state is a sovereign,

each state sets its own laws and has its own Constitution. In addition, the United States federal

government makes laws and has a Constitution.

When determining whether a legal issue is governed by federal or state law, keep in mind

that some areas of the law, such as criminal and environmental law, are governed by both state

and federal laws. Generally, the principle of preemption means that a legitimate federal action

supersedes a state law in certain cases. Although a full discussion of preemption is beyond the

scope of this handout, you should be aware of some basic principles. Federal law preempts state

law when the two laws conflict, when Congress expressly or implicitly says so, or when federal

laws are so pervasive that they occupy the entire field of law.

Hypothetical Case: Pick-Pocketing in Virginia

There is no preemption issue in your case because there is no conflict between state and

federal law such that federal law would override Virginia state law. Specifically, there is no

federal law prohibition against pick-pocketing that could conflict with Virginia’s local pick-

pocketing law. So, two sets of laws potentially govern.

3

Federal Issues

State Issues

• Your Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendment

rights were triggered once you were

arrested—these rights are governed by

federal law, i.e., the U.S. Constitution.

2

• Virginia’s or the town’s local pick- pocketing

statute will lay out the elements of and

punishment for the offense; the court’s

decision in your case will also be informed by

state cases about pick-pocketing.

• Your arrest might also implicate Virginia’s

state Constitution—state Constitutions must

provide at least as many rights as the Federal

Constitution, but can also entitle you to

broader protections.

In sum, your case involves legal issues governed by both state and federal law.

Step 2: Which Court Are You In?

Next, determine which court you are in, which is a two-part inquiry.

(1)

First, ask yourself whether you are in federal or state court.

Dual sovereignty means that each sovereign has its own court system: the

states each have courts and the United States has courts, which are called

federal courts. Federal courts are located throughout the United States.

(2)

Second, ask yourself whether you are in a trial court, an intermediate appellate court,

or a supreme court.

Most American court systems—whether they are federal or state—have a

similar structure, consisting of trial courts, intermediate appellate courts, and

the highest court in the jurisdiction, usually supreme courts. In the federal

court system, the trial courts are called United States District Courts. There

are twelve federal courts of appeals that each cover a geographical region

called a circuit and are, accordingly, called the United States Court of Appeals

for the [insert number] Circuit or Circuit Courts.

3

States vary in the names

they give to their courts, but regardless of the nomenclature, the structure is

the same.

4

2

Usually, there are state cases adopting Federal Courts’ interpretation of the Constitution. If this is so, you should cite your state

case. Be careful, though, to check and see if there are any new federal decisions governing basic Constitutional rights

surrounding your case.

3

Additionally, there is a thirteenth federal appellate court called the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which unlike the

regional Circuit Courts of Appeal, has nationwide jurisdiction to hear appeals in only certain types of cases including cases

involving patent laws and cases appealed from the U.S. Court of Federal Claims and the U.S. Court of International Trade.

4

In some states, such as New York and Maryland, the highest court in the state is actually called the Court of Appeals.

4

Hypothetical Case: Pick-Pocketing in Virginia

In your case, the local police arrested you. These police were acting under the authority

of the Virginia state or local statute against pick-pocketing. Thus, at this point, you are in a

Virginia state trial court. Realize, though, that even though you are in a state court, the federal

Constitutional issues you identified in step 1 can still be heard by that court.

If you lose at trial and need to appeal, that appeal will go to Virginia’s intermediate

appellate court, and then to Virginia’s highest court, the Virginia Supreme Court. Only if you

lose at the state’s highest court and believe that the state law violates the U.S. Constitution can

you appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

If you had been arrested by the FBI or for a federal offense, then you could be tried in

federal district court, perhaps in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. If

the case were appealed, it would go to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, then to

the U.S. Supreme Court.

In sum, at this point, your case is in a state trial court for the purpose of determining

whether a particular case is binding or persuasive.

NOW YOU ARE READY! Is the case you have found binding or persuasive?

Now that you have found a case on point, some general principles will help you to figure

out whether a law is binding or persuasive. Use your answers to the above questions to apply

these principles to your case.

First, higher courts bind lower courts within their particular state or circuit. With the

exception of the U.S. Supreme Court, courts of appeals and state courts do not bind courts

outside the state or circuit in which they are located. That is, a federal Supreme Court decision is

binding on all lower federal courts, both circuit courts of appeals and district courts. A federal

circuit decision is binding on all federal district courts within its circuit, but not federal courts in

other circuits. For example, a decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit binds

the U.S. district courts within the Ninth Circuit, but not federal courts in any other circuit.

However, a district court or trial court decision would not bind higher courts. A decision by a

state’s highest court is binding on all appeals courts and trial courts in that state, but not on state

courts in other states, and usually, a state court of appeals’ decision binds state trial courts in that

state.

5

Second, with the exception of the U.S. Supreme Court, federal courts bind only other

federal courts, not state courts. Thus, a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth

Circuit, a federal court, is binding on federal district courts within the boundaries of the Ninth

5

Although some states have appellate courts that bind all lower courts in the state, others have regional districts or circuits and a

state appellate court may bind only lower courts within its geographic district or circuit. Therefore, be sure to research the

structure of the courts in your particular state. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/academics/academic-resources/the-writing-

center/guides-and-handouts/matthew-schafer-federallawfederalcourtsandbindingandpersuasiveauthority-2/

5

Circuit. It is not binding on California state courts, even though California is geographically

within the Ninth Circuit. Similarly, state courts bind only other state courts within the state.

A decision of the California Supreme Court would thus bind other California state courts, not

state courts in any other state. However, sometimes a federal court must apply a state’s law. In

that case, the state’s interpretation of that law is binding on the federal court. Therefore, a

California Supreme Court decision on a matter of California law would bind federal courts on

that state law issue. Similarly, state courts must sometimes decide issues of federal law, but they

are not bound by federal courts except the U.S. Supreme Court. A decision of the U.S. Supreme

Court, a federal court, is binding on state courts when it decides an issue of federal law, such as

Constitutional interpretation.

Hypothetical Case: Pick-Pocketing in Virginia

Federal Issues

State Issues

• The Constitutional issues are federal. The

state trial court is thus bound by the U.S.

Supreme Court’s decisions about the

Constitutional issues in your case.

• Any decisions from other federal courts

other than the U.S. Supreme Court are

persuasive authority on the federal law

issues.

• Note that if you had been accused of a

federal offense, you probably would have

appeared in a federal district court, which

would have been bound by the court of

appeals for your circuit (i.e., the Fourth

Circuit), and the U.S. Supreme Court on all

federal issues.

• The Virginia state trial court in which your

case will be heard is bound by Virginia

courts of appeal and by the Virginia

Supreme Court on all state issues. Because

the pick-pocketing law is a state law issue,

the state’s courts of appeals and state

supreme court decisions will bind the state

trial court you are in.

• All other court decisions are persuasive

authority on the state law issue—that is,

decisions from all federal courts, other

states’ state courts, and other state trial

courts in the same state.

Applying this analysis from the outset will help you to be a smarter, faster researcher and

to narrow down the body of case law at which you are looking. Knowing what the court is

bound to follow will help you to write more effective memos, motions, and briefs.

For a more detailed discussion of binding and persuasive authority at the federal level,

see the Writing Center’s handout, “Federal Law, Federal Courts, and Binding and Persuasive

Authority.” Also, for a discussion about using persuasive authority in your legal writing, see the

following handout: “When and How to use Secondary Sources and Persuasive Authority to

Research and Write Legal Documents.”

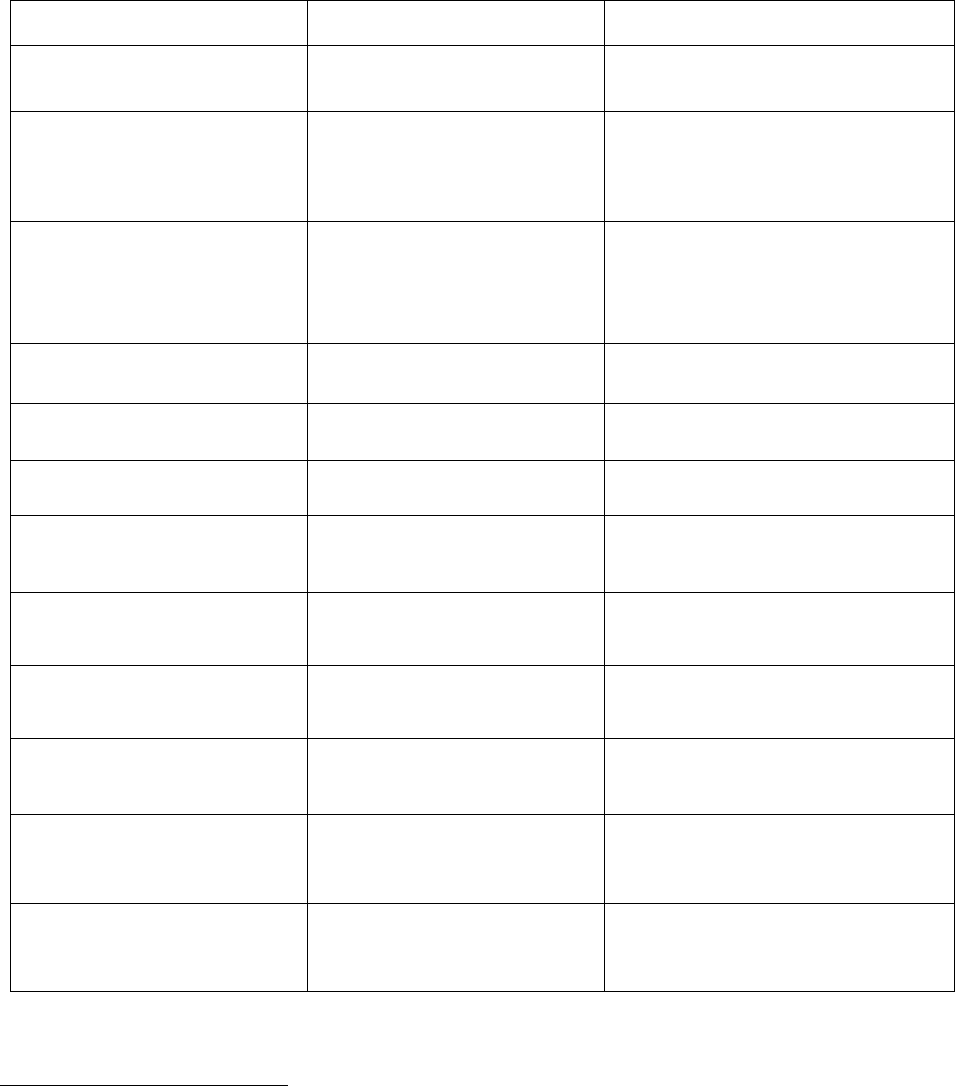

The table below displays the above principles in another form. Use your answers from Steps 1

and 2—whether the issue is state or federal and which court you are in—to find the box in the

6

left hand column that applies to your case. Then, read across that row to find out which courts

bind you and which courts are only persuasive to you.

7

1)

State or Federal Issue?

2)

Which court are you in?

Binding Authority

Persuasive Authority

State issue in state trial court

That state’s state appeals court

That state’s highest court

All federal courts

Other states’ state courts

Other state trial courts in the same state

State issue in state appeals court

That state’s highest court

All federal courts

Other states’ state courts

State trial courts in the same state

Other state courts of appeals in the same

state

State issue in state’s highest court

N/A

That state’s highest court

*

State trial courts in the same state

State courts of appeals in the same state

Other states’ state courts

All federal courts

State issue in federal district court

Interpretations from the state’s

highest court

All federal courts

Other state courts

State issue in federal circuit court

Interpretations from the state’s

highest court

All federal courts

Other state courts

State issue in U.S. Supreme Court

Interpretations from the state’s

highest court

All federal courts

Other state courts

Federal issue in state trial court

U.S. Supreme Court

That state’s court of appeals

That state’s highest court

All federal district courts

All federal circuit courts

State courts

Federal issue in state appeals court

U.S. Supreme Court

That state’s highest court

All federal district courts

All federal circuit courts

State courts

Federal issue in state’s highest

court

U.S. Supreme Court

All federal district courts

All federal circuit courts

State courts

Federal issue in federal district

court

U.S. Supreme Court

Federal circuit court in the circuit

where the district court is

Other federal circuit courts

Federal district courts

All state courts

Federal issue in federal circuit court

U.S. Supreme Court

That federal circuit court

*

Other federal circuit courts

Other federal district courts

All state courts

Federal issue in U.S. Supreme

Court

N/A

U.S. Supreme Court

*

All federal circuit courts

All federal district courts

All state courts

*

Technically, courts of the same level do not bind each other. Thus, the U.S. Supreme Court may overturn its prior decisions,

though it has adopted different practices of stare decisis for its constitutional precedents and its precedents interpreting federal

statutes. For a discussion of stare decisis practices of the U.S. Supreme Court, see Amy Coney Barrett, Statutory Stare Decisis in

the Courts of Appeals, 73 G

EO. WASH. L. REV. 2 (2005). Further, although federal circuit courts technically do not bind

themselves, nearly every circuit court has adopted a strong rule of stare decisis, or “law of the circuit” rule, under which the

holding of a published decision by a three-judge panel of the circuit binds subsequent panels. Joseph W. Mead, Stare Decisis in

the Inferior Courts of the United States, 12 N

EV. L. J. 787, 794–95 (2012). Therefore, in practice, a published circuit court

opinion is generally binding on that court. Id. However, “law of the circuit” rules vary slightly by circuit. Id. at 797.