Copyright © Minister for Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth, 2021

Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth

Block 1, Miesian Plaza, 50 – 58 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin 2

D02 XW14

Tel: +353 (0)1 647 3000

Email: research@equality.gov.ie

Web: www.gov.ie/dcediy

The Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth

should be acknowledged in all references to this publication.

For rights of translation or reproduction, please contact the Department of

Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth.

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

ii

Contents

Purpose of the Evidence into Policy Guidance Notes .......................................................... 1

Key Messages ................................................................................................................................. 1

1. What is an Evaluation Framework? ..................................................................................... 2

2. Programme Logic Models ....................................................................................................... 3

Core elements of a Logic Model ............................................................................................. 4

Logic Modelling: Examples ....................................................................................................... 4

The Kellogg Foundation Logic Model .................................................................................... 5

The Wisconsin Model .............................................................................................................. 7

Creating a Logic Model ............................................................................................................. 8

Benefits and Limitations of a Programme Logic Model .................................................. 10

3. Theories of Change ................................................................................................................. 11

4. Evidence, Monitoring and Evaluation ................................................................................ 14

Using Indicators ........................................................................................................................ 14

5. Linking Frameworks to Evaluation ..................................................................................... 16

Note: the material contained in this Evidence into Policy Guidance

Note has been adapted from the DCEDIY’s 2-day “Understanding

Evaluation in Human-Related Government Services” training course

for Civil Service staff. The course content was developed in

collaboration with colleagues from the Centre for Effective Services

under the Goal Programme for public service reform (an Atlantic

Philanthropies initiative to support systemic change in public services

in Ireland and Northern Ireland).

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

1

Purpose of the Evidence into Policy Guidance

Notes

The Evidence into Policy Guidance Notes are produced by the Research and

Evaluation Unit within the DCEDIY to help support policy units in driving the

research-to-policy cycle. These guidance notes provide advice and information on

key stages of the research to policy process, in support of evidence-informed

policymaking.

Building on Guidance Note #3: “Evaluating Government-Funded Human Services”,

“Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation” explores the role and importance of

frameworks for both planning and evaluating projects, policies and programmes. The

guidance note is presented under the following headings:

1. What are Policy Planning and Evaluation Frameworks?

2. Programme Logic Models

3. Theories of Change

4. Evidence, Monitoring and Evaluation

5. Using Indicators

Key Messages

• A Framework provides a structure for both planning and evaluating a project, policy

or programme.

• A Logic Model is an example of a Policy Planning and Evaluation Framework. Logic

Models typically include five key elements: Inputs, Activities, Outputs, Outcomes

and Impacts.

• A Logic Model is underpinned by a Theory of Change, which details the assumptions

underpinning the rationale for an intervention, according to a series of ‘if-then’

relationships.

• A Policy Planning and Evaluation Framework should be developed in consultation

with key policy or programme stakeholders, and based on robust evidence.

• Measurable performance indicators should be identified early in the policymaking

process and monitored on an ongoing basis. Indicator data are key to meaningful

evaluations.

• Evaluations based on a clear policy or programme framework may be more credible

and communicable to stakeholders.

• Credibility and communicability will support the translation of evaluation findings

into policy action, thereby supporting evaluation effectiveness.

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

2

1. What is an Evaluation Framework?

A Policy Planning and Evaluation Framework sets out your overall approach to

measuring impact and documents the assumptions underpinning your vision for how

an intervention will lead to identified changes. The Public Spending Code (2019)

stipulates that a Strategic Assessment Report, a document which represents the first

stage in the Project Life Cycle, must include a:

Framework for determining key performance indicators for the proposed

intervention… measuring inputs, outputs, results and impacts such as a logic path

model. (Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, 2019)

1

Establishing how an intervention will lead to the desired changes in a target

population can be difficult, since assumptions must be made about what will happen

in the future. Furthermore, even if a link between an intervention and population

change can be established, not all stakeholders may agree on what aspects of an

intervention have shaped these changes. This may lead to challenges in deciding on

an evaluation question and approach. An evaluation framework can help with this

process, as it:

shapes the overall approach or ‘guiding principles’ that will be taken to monitor

activities and outputs, and to assess impact. (Innovate UK, 2018)

2

As stated in the UK Treasury’s ‘Magenta Book’:

Establishing a framework for evaluation provides a consistent and systematic means

to designing the evaluation, collating and analysing the existing evidence and the new

data created, and generating and interpreting the results. (HM Treasury, 2011)

3

If the framework is designed, agreed upon and implemented in advance of

programme rollout, it can minimise uncertainty around future evaluation objectives.

Useful, and commonly used, examples of frameworks that can be applied to policy

planning and evaluation include Programme Logic Models and/or Theories of Change.

1

Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, 2019. Public Spending Code: A Guide to Evaluation, Planning and

Managing Public Investment, Dublin: Government of Ireland.

2

Innovate UK, 2018. Evaluation Framework: How we assess our impact on business and the economy, London: UK

Government.

3

HM Treasury, 2011. Magenta Book: Central Government guidance on Evaluation, London: UK Government.

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

3

These frameworks can be used in isolation, but the process of developing a Theory of

Change can help to inform the development of the Logic Model and vice versa.

Frameworks help to ensure that evaluations are included in the broader planning

process, from the outset.

2. Programme Logic Models

Key to the development of a new policy or programme will be the identification of

specific objectives, including the desired policy/programme impacts and the target

populations, industries or social activities. Policymakers must identify constraints to

achieving these objectives, such as budget, time, and resources. These constraints,

coupled with complexities relating to broader social and economic trends, often lead

to uncertainty regarding when and how a policy/programme has achieved its

objectives. This uncertainty arises in the evaluation process when trying to link a

policy/programme to identified outcomes. A Programme Logic Model, developed

and agreed in the early stages of the policymaking process, can help to frame an

evaluation, by providing a roadmap for policy/programme implementation that

accounts for both direct (e.g. staffing and resourcing) and indirect (e.g. broader social

and economic) constraints.

A Programme Logic Model can clarify the connections between government policy

and identified outcomes, by providing a structured format for communicating the

rationale behind a policy, and its anticipated impacts. A well-constructed Logic Model

outlines the key elements of a policy/programme, which enables evaluators to focus

their evaluation questions on key policy/programme features that are of real value to

stakeholders.

As a ‘road map’, a Programme Logic Model can show where we are currently, where

we would like to be, and what we’ll need to do to get there. It can therefore be useful

in determining whether or not we have deviated from our chosen path and, if so, by

how much or to what extent.

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

4

Core elements of a Logic Model

There is a broad range of approaches to logic modelling, but it is possible to describe

with five common elements:

Inputs

The resources needed in order to implement a policy or

programme. Inputs enable activities and subsequent outputs.

Examples include staff, funding, buildings, technology,

information systems, and support structures.

Activities

The process of converting inputs into outputs; what needs to

be done. Activities are the actions and processes that bring

about intended future changes.

Outputs

The product/service that has been delivered - the 'completed'

activity. Outputs will generally be tangible and measurable (i.e.

the number of forms processed, the uptake of a new scheme,

etc.)

Outcomes

The intended (or unintended) changes that occur as a result of a

policy, intervention or service. Logic Models typically present

outcomes as short or medium-term changes. These may be

difficult to determine as other contextual factors come into

play, which makes outcomes more difficult to measure than

outputs. Difficulties may also arise in attributing a given

outcome to a specific policy or intervention, that is, the extent

to which we can say that an outcome has occurred as a direct

result of an intervention.

Impacts

Longer-term economic and social changes. For example, the

change in the wellbeing of a target group over a number of

years. Attributing longer-term impacts to a single policy or

programme may be difficult, and require considerable

evaluation resourcing.

Logic Modelling: Examples

Some common approaches to Programme Logic Modelling are presented below.

These examples demonstrate the adaptability of Logic Models. A Logic Model should

enable users to work systematically through the connections between the

components of policy/programme implementation. Wherever possible, it should be

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

5

presented in a graphical format on a single page, in order to support clarity and

simplicity. Logic Models may be modified over time, as connections and components

change.

The Kellogg Foundation Logic Model

Figure 1. The Kellogg Foundation Logic Model (Kellogg Foundation, 2004: 3)

The Kellogg Foundation, (a large US based-philanthropic foundation), developed the

Logic Model structure displayed in Figure 1. Their Logic Model is a systematic, visual

representation of planned work and intended results (W.K. Kellogg Foundation,

2004).

4

This Model includes all of the ‘core’ elements discussed previously. Note:

Figure 1 also includes the ‘if- then’ statements which can be described as the Logic Model’s

Theory of Change (Theories of Change will be discussed in more detail later in Section 3 of

this Guidance Note).

4

W.K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004. W.K. Kellogg Foundation Logic Model Development Guide, Michigan: W.K. Kellogg

Foundation. See: https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/LogicModel.pdf

Certain

resources are

needed to

operate your

program

Resources

/Inputs

1

If you have

access to

them, then

you can use

them to

accomplish

your planned

activities

Activities

2

If these

benefits to

participants

are achieved,

then certain

changes in

organizations,

communities,

or systems

might be

expected to

occur

Impact

5

If you

accomplish

your planned

activities,

then you will

hopefully

deliver the

amount of

product

and/or

service that

you intended

Outputs

3

If you

accomplish

your planned

activities to

the extent

you intended,

then your

participants

will benefit in

certain ways

Outcomes

4

Your Planned Work Your Intended Results

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

6

Example 1: Using ‘The Kellogg Foundation Logic Model’ to plan a family holiday

5

Background

The Murphy family would like to go on an inexpensive family trip to visit relatives,

during the Christmas school holidays.

Assumptions

• The Murphys want to take their trip during the three weeks in December and

January that their children are not in school. So, they must travel between the

11th of December 2021 and the 3rd of January 2022.

• The Murphys live in South Carolina in the USA, and their relatives live in Iowa.

They could drive, but they have enough frequent flier miles saved to fly for

free so they intend to do this, to save both time and money on travel costs

(W.K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004, p. 3). They have developed a Logic Model for

their holiday, as follows, which includes target (short term) outcomes, as well

as the desired longer term impact of their trip:

Figure 2. Kellogg Foundation Logic Model: The Murphys’ Christmas Trip to Iowa (adapted from

Kellogg Foundation, 2004: 4)

5

Adapted from: Kellogg Foundation, 2004: 4

• Holiday

flight

schedules

• Family

schedules

• Frequent

flyer

holiday

options

• Holiday

weather

• Create

family

schedule

• Get holiday

flight info

• Get tickets

• Arrange

ground

transport

• Continued

good family

relations

• Tickets for

all family

members

• Frequent

flyer miles

used

• Money

saved

• Family

members

enjoy

vacation

1

2

5

3

4

Resources

/Inputs

Activities

Impact

Outputs

Outcomes

Your Planned Work

Trip Planning

Your Intended Results

Trip Results

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

7

The Wisconsin Model

Figure 3. The Wisconsin Logic Model (Evaluation Support Scotland, 2009)

6

Another common format for logic modelling comes from the University of

Wisconsin’s ‘United Way’ programme. The Wisconsin Model begins by outlining the

existing situation or need for the policy or programme. This should be clear and

unambiguous. The Model then includes inputs and outputs (split into activities and

the relevant participants), and breaks outcomes into short, medium and long-term

expected outcomes. This model also considers the assumptions underpinning the

programme, as well as external factors that may influence the achievement of desired

outcomes.

Example 2: Using ‘The Wisconsin Model’

Situation/need: It is lunchtime and John is hungry. He needs to eat, has an hour-long

lunch break and a budget of €6.

Assumption: John has enough inputs to acquire food, i.e. enough money and time to

buy a meal e.g. €6 to buy a burrito in his local takeaway, which is walking distance

from his house. It is assumed that the walking, queueing and ordering times fall within

his hour-long break time. This may not always be possible, especially on Fridays,

which are particularly busy.

6

Evaluation Support Scotland, 2009. Evaluation Support guide 1.2: Developing a Logic Model, Edinburgh: Evaluation

Support Scotland.

Situation

/ need

Inputs

Outputs

Assumptions

External factors

Activities

Participants

Outcomes

Short

term

Medium

term

Long

term

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

8

Activities: John walking to his local takeaway and ordering and paying for his burrito.

Output: Once John has engaged in these activities and used his inputs (time and

money) he will receive a burrito in return (the output).

John will then eat the burrito, which will satisfy his hunger (short-term outcome),

make him feel better for the afternoon (medium-term outcome) and depending on

nutritional content, will fulfil some of his daily nutritional needs, while also ensuring

ongoing work performance (longer-term outcome). John’s actions will also generate

direct economic outcomes for the restaurant that he buys it from, and indirect

outcomes for the wider local economy. Under the Wisconsin model, external factors

that could affect these outcomes and outputs may include: food poisoning as a result

of the burrito; the sudden closure of the takeaway shop (due to economic or other

factors); or other unrelated external factors that inhibit John’s work performance.

Figure 4. Example of the Wisconsin Logic Model

Creating a Logic Model

A common starting point when developing a Logic Model is to conduct a situation

analysis. This involves policymakers and stakeholders asking questions like:

• What is the issue that we need to address?

• What are the needs of the population and target groups?

• What are the strengths and weaknesses of the current provision?

• Where are the gaps?

What assumptions are we making?

Situation

H

U

N

G

R

Y

Get food

(Input)

Eat food

(Output)

Feel better

(Outcome)

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

9

• What do we need to improve?

• What are the key socio-economic influences?

7

Once you have documented the situation, you can start working on defining the key

objectives, or policy/programme outcomes. As mentioned previously, outcomes are

the intended and unintended changes that occur as a result of a policy intervention or

service. Identifying your target outcomes, from the outset, can help you to specify

what activities will best help you achieve your objectives, along with the types of

activities and outcomes data you will need to collect. You may also wish to consider

longer-term impacts at this time.

Outcomes (and longer-term impacts) can occur at the individual, community,

organisational, and service levels. They can be grouped into short and medium-term

outcomes, as well as longer-term outcomes or impacts. Individual, community,

organisational and service level outcomes could include changes to attitudes,

behaviours and status. These can happen in both the short and medium term. Longer-

term outcomes and impacts refer to long-run changes at these levels, but can also

occur at a broader societal level. Depending on the size of a policy or programme, the

latter might include reductions in poverty or homelessness in society as a whole

(Wyatt Knowlton & Phillips, 2012:37).

Once the policy/programme objectives, outcomes and impacts have been defined,

consideration must be given to inputs, activities and outputs. A key consideration is

that inputs, such as funding, staffing and other resources, will enable and/or constrain

the types of activities undertaken which, in turn, determine the level of

policy/programme outputs. Activities encompass decisions around what you and your

staff and stakeholders will do, when and how it will be done, and frequency of

activities. Outputs will reflect the numbers of people, organisations, or other units of

analysis targeted by the policy/programme targeted by the policy/programme (Wyatt

Knowlton & Phillips, 2012).

8

Given the sequential nature of each of these stages, it

7

Knowlton, L. & Phillips, C. (2013). The Logic Model Guidebook. Better Strategies for Great Results. Second

Edition. Sage Publications. Available at: https://us.corwin.com/sites/default/files/upm-

binaries/23938_Chapter_3___Creating_Program_Logic_Models.pdf

8

Wyatt Knowlton, L. & Phillips, C. C., 2012. The Logic Model Guidebook. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

10

may seem logical to begin with inputs, however you may work through the stages

according to specific policy/programme requirements. Although the Logic Model

examples provided above read from left to right, this is not necessarily the order in

which you (and/or stakeholders) may wish to develop your thinking. As mentioned

previously, Programme Logic Models provide flexibility and therefore you may

develop a model structure to suit your needs.

Benefits and Limitations of a Programme Logic Model

A Logic Model is a conceptual tool that will help you to think through and plan your

policy or programme, provide a framework for future evaluations, or help you to

frame an evaluation of a policy or programme that does not have a Logic Model or

Theory of Change.

Like any tool its value will be depend on how it is used. Logic Models can:

• Help clarify what a policy/programme aims to achieve, both in the short and

longer- term, and what is required to achieve it.

• Help to manage expectations and set out clear and shared goals, as well as

deliverables, thereby reducing ambiguity.

• Support efficient use and allocation of resources, by identifying the resources

required to deliver a policy, such as the inputs needed to undertake key

activities, and how to best allocate staff to ensure the achievement of output

targets.

• If developed collaboratively between policymakers and key stakeholders, logic

modelling can help build working relationships and improve communications,

which helps promote successful implementation. This may be of particular

value when operating in a complex social and economic policy context.

A limitation of logic modelling, and indeed any planning or evaluation tool, is that it

may oversimplify the relationships between the individual implementation stages.

There is a risk of omitting important factors, so that the Logic Model does not present

a full picture. A Logic Model can fail to give adequate attention to processes involved

in moving from inputs to outputs, or how outputs become outcomes/impacts. Real

world policies/programmes are seldom linear or sequential, as they are typically

illustrated within a Logic Model. This limitation can be addressed by ongoing

monitoring of the assumptions underlying the Logic Model, as well as the internal and

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

11

external factors affecting policy/programme implementation. As policies/programmes

are delivered in dynamic social and economic environments, Logic Models must be

adaptable, and must be used with a willingness to evolve the models as part of the

implementation process.

3. Theories of Change

Underpinning a Logic Model is a policy/programme’s Theory of Change. The various

components of a Logic Model are most easily identifiable when the intended causal

relationship between them has been conceptualised. This is generally presented as a

series of ‘if-then’ relationships that link back to a Logic Model’s inputs, activities,

outputs, outcomes and impacts. In the example presented in ‘Figure 5: Theory of

Change’, if I have access to resource A, then I can complete activity B. If activity B has

been completed, then we would observe C as an output. If we can achieve C as an

output, then D, E and F can be achieved.

Figure 5. Theory of Change

However, a Theory of Change can also act as a useful stand-alone framework for

policy planning and evaluation. They can help to describe the steps required in

delivering a policy outcome. For example, if the government’s high-level goal was to

avoid illness among children by preventing the spread of a disease, they could set the

policy goal of vaccinating 95% of children aged 0-5 years. In this scenario the

following if-then statements would apply:

• If the government has access to vaccine doses (and other key resources), then

these can be supplied to the relevant staff.

• If these staff can be trained and deployed to administer the vaccines in the

relevant settings, then the vaccination service can be offered to parents of the

target age group.

If - Then

A

B C D E F

If - Then

If - Then

If - Then

If - Then

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

12

• If enough parents are willing to bring their children to be vaccinated, then the

government’s vaccination targets can be reached and a public health policy

goal will be achieved.

In terms of theorising contingencies, if there is a shortfall in the supply of resources,

then timelines and supply contracts will need to be reviewed. If the required numbers

of parents do not bring their children for vaccination, then the government will need

to consider an advertising campaign to encourage increased uptake, and so on.

While a Programme Logic Model illustrates linkages between each programme

element, it is the Theory of Change that explains why these connections have been

proposed, and connects these steps to the overall policy objective. The example

provided in ‘Figure 6: Theory of Change Example: Investment in Education’ proposes

that if the government invests in education (as an input and activity), then the

economy will be supplied with a more educated workforce (as an output). If the target

outcome from this investment is economic growth, then this will be achieved when

the more educated workforce takes up better-paid jobs, set up businesses, and create

an attractive jobs market for increased foreign direct investment.

Assumptions underpinning the Theory of Change should be informed by evidence

regarding optimal modes of investment, labour market trends, and broader economic

goals. For example, the pharmaceutical and technological sectors are significant

components of the Irish economy; therefore Ireland’s investment in Science

Foundation Ireland, the Irish government’s national research funding body for

investment in science and engineering, can be viewed as a form of investment in both

academia and in an industry that is key to both employment and economic growth

(DFHERIS, 2021);

9

(SFI, 2017).

10

Such investment has been identified within these

sectors as being a key incentive for Foreign Direct Investment (DBEI, 2020).

11

Therefore, equipped with this evidence, and following an assessment of labour

9

DFHERIS, 2021. Press Release: Minister Harris announces €193 million investment in five world- leading SFI Research

Centres. [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/a1d97-minister-harris-announces-193-

million-investment-in-five-world-leading-sfi-research-centres/ [Accessed 16 March 2021].

10

SFI, 2017. Science Foundation Ireland: About Us. [Online] Available at: https://www.sfi.ie/about-us/ [Accessed

March 16 2021].

11

Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation, 2020. Working to Progress Ireland’s Trade and Investment

Objectives. [Online]

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

13

market trends, assumptions relating to the example provided in Figure 6 may include

that if the government focuses its investment in science, technology, engineering and

mathematics (STEM subjects)

12

then the economy will be supplied with a more

educated workforce that matches the government’s targets regarding economic

growth via FDI in the pharmaceutical and technological sectors.

Example: Applying the Theory of Change to Investment in Education

Figure 6. Theory of Change Example: Investment in Education

As with Logic Models, a Theory of Change provides an adaptable tool for

policymakers that aids in policy or programme development. It can also act as a useful

tool for collaborating with stakeholders, as part of initial consultations regarding

shared policy objectives, identifying underlying assumptions, and understanding the

steps needed to achieve key objectives.

At the same time developing a Theory of Change will help to provide a roadmap for

future evaluation. It may be used to help build in a framework for evaluations as part

of the policy planning process, or it may be developed retrospectively to help frame

an evaluation of a policy or programme that does not have one.

Decision-making around whether to develop a Theory of Change, Logic Model or

combination of both may be informed by policy or programme complexity,

implementation timelines, approaches to stakeholder consultation, personal,

organisational or stakeholder preferences, as well as planning around monitoring and

evaluation.

12

Department of Education, 2016. A Report on Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) Education:

Analysis and Recommendations - The Stem Education Review Group, November 2016. Available at:

https://www.education.ie/en/publications/education-reports/stem-education-in-the-irish-school-system.pdf

(Accessed 20.04.2021)

Investment in

education

Economic

growth

A more educated workforce

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

14

4. Evidence, Monitoring and Evaluation

Regardless of the planning tool used, it is recommended that monitoring and

evaluation occur across the policy life cycle, and should be built in from the very

beginning.

13

Designing evaluation at the outset of the policy process will enable the

collection of relevant data on programme implementation. Programme Logic Models

and Theories of Change can provide a shared framework for decision-making on the

types of data and processes that need to be collected and monitored, so that

progress on each of the key elements involved in implementation can be assessed

throughout the policy life cycle.

Monitoring reports and implementation data provide evaluators with material for

meaningful evaluation. Without this information, an evaluation may suffer from lack

of focus or direction, or may not have access to necessary data.

Using Indicators

Targets and indicators provide signals of progress, as you implement a policy or

programme. As noted by the DCEDIY (2014, p. 6):

14

An indicator provides evidence that a certain condition exists or that certain results

have or have not been achieved. In the context of public policy, indicators enable

decision-makers to track progress towards the achievement of intended outputs,

outcomes, goals, and objectives.

Indicators can provide metrics relating to the inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and

impacts of a policy or programme. While indicators may not always explain why a

result is (or is not) achieved, (e.g. where broader socioeconomic, cultural or other

external factors influence policy performance), they may usefully be rooted in a

Programme Logic Model or Theory of Change, and benchmarked against agreed

targets. Again, collaboration with stakeholders is advised when developing

13

For example, the OECD and SIGMA have developed a toolkit that provides guidance on evaluating government

strategies, in particular strategies aimed at Public Sector reform. This toolkit is available here: https://www.oecd-

ilibrary.org/governance/toolkit-for-the-preparation-implementation-monitoring-reporting-and-evaluation-of-

public-administration-reform-and-sector-strategies_37e212e6-en

14

DCYA, 2014. Better Outcomes Brighter Futures: The national policy framework for children & young people 2014-

2020, Dublin: Department of Children and Youth Affairs.

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

15

performance indicators (OECD, 2019),

15

(OECD & SIGMA, 2018). This helps to

ensure that the indicators are measurable and relevant to the people involved in

implementation (Brown, 2009).

16

Three common indicator types are: ‘process

indicators’; ‘output indicators’; and ‘outcome/impact indicators’. These indicator types

correspond to the dimensions outlined in a Programme Logic Model, with ‘process

indicators’ relating to inputs and activities.

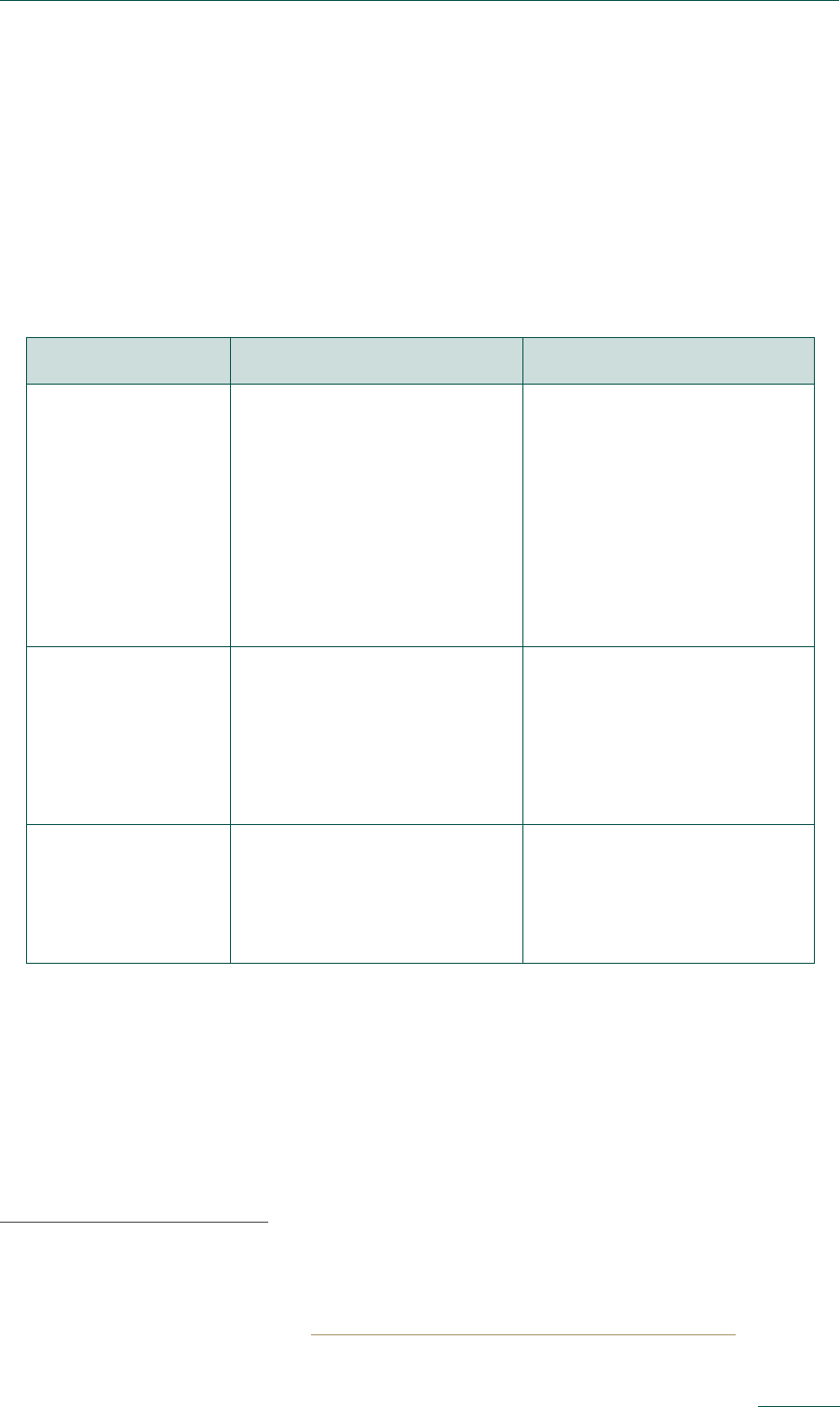

Indicator Description Example

Process

indicators

Measure how effectively

or efficiently an

organisation is carrying

out its work

How long were service

users waiting to see the

adviser? Does this

correspond with

expectations? What were

the key factors

underpinning this

performance level?

Output

indicators

Measure the extent to

which a programme’s

activities are being carried

out

How many service users

have seen an adviser?

Did we expect more or

less service users to see

an adviser?

Outcome/Impact

indicators

Measure the degree to

which outcomes and

impacts are being

achieved

What change has the

programme made for

service users?

Figure 7. A Typology of Indicators (OECD, 2019)

When developing indicators, the following key criteria can help to ensure accuracy

and value. This will be particularly important when monitoring implementation, and

when engaging in policy or programme evaluation:

15

OECD, 2019. Chapter 5. Building a monitoring and evaluation framework for open government in Argentina. In:

Open Government in Argentina. Paris: OECD.

16

Brown, D., 2009. Good Practice Guidelines for Indicator Development and Reporting: A contributed paper Third

World Forum on ‘Statistics, Knowledge and Policy’, Charting Progress, Building Visions, Improving Life, 27-30 October

2009 Busan, KOREA. [Online] Available at: https://www.oecd.org/site/progresskorea/43586563.pdf [Accessed

March 16 2021].

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

16

Action-focused Indicators should reflect specific measurable actions

Important

Only measure what matters. When designing an indicator

set, it is crucial to keep stakeholder needs in mind

Specific

The indicator should provide a clear description of what is

being measured

Simple Language used should be accessible, clear and concise

Measurable

Collecting and analysing information must be possible with

the methods and resources available

Figure 8. Key Elements for Indicators (UN AIDS, 2010, p. 26)

17

5. Linking Frameworks to Evaluation

A Programme Logic Model or Theory of Change provides a useful benchmark against

which the success (or otherwise) of a policy or programme can be measured, thereby

providing a useful framework for evaluation. A well-developed framework can

provide clarity for evaluators around key policy or programme objectives, the key

steps taken, and resources used to achieve these objectives. This helps remove a

degree of uncertainty, which may be common when evaluating complex policy areas,

such as those relating to ‘human services’

18

. When undertaking an evaluation, the use

of one of these frameworks can help to answer questions such as:

• Are the policy goals clear? – Do the ‘if-then’ links between policy formation

and outcomes follow a logical sequence; are there gaps in this sequence?

• Are we asking questions about inputs, activities, outputs or

outcomes/impacts?

• What will we measure? What links/components in the Logic Model is it useful

for us to know about?

• What indicators will help us to answer these questions? Do we need to assess

process, output or outcome/impact indicators?

• Does indicator data already exist or will we need to collect new data?

17

UN AIDS, 2010. An Introduction to Indicators. [Online]

Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/sub_landing/files/8_2-Intro-to-IndicatorsFMEF.pdf

[Accessed 16 March 2021].

18

‘Human services’ can be defined as activities, approaches, services or policies that seek to meet ‘human needs’

through an ‘interdisciplinary knowledge base, focusing on prevention as well as remediation of problems, and

maintaining a commitment to improving the overall quality of life of service populations.’ (National Organisation

for Human Services, USA). See: https://www.nationalhumanservices.org

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

17

The establishment of clear evaluation questions rooted in a policy framework,

coupled with the identification of available data (and data gaps), provides a robust

starting point for decision-making on how to approach an evaluation. Monitoring and

indicator data provide a key evaluation resource, which may be sense checked on an

ongoing basis against the policy framework. Once completed, evaluation findings may

be assessed against key framework-based criteria, thereby supporting the

communicability and credibility of findings. This will be particularly relevant where

frameworks have been developed in collaboration with key stakeholders. Credibility

and communicability will in turn support the translation of evaluation findings into

policy action, thereby supporting evaluation effectiveness.

Ruadhán Branigan

Dearbhla Quinn

Ciarán Madden

Research & Evaluation Unit | May 2021

Would you like to register your interest

in participating in our next Evaluation

Training Programme?

If so, please contact the Evaluations

team at [email protected] or

phone Dearbhla Quinn (01 6642073)

or Ciarán Madden (01 6473123).

Frameworks for Policy Planning and Evaluation | Evidence into Policy Guidance Note #7

18