2022, Vol. 66(2) 217 –245

What’s Fair in

International Politics?

Equity, Equality, and

Foreign Policy Attitudes

Kathleen E. Powers

1

, Joshua D. Kertzer

2

,

Deborah J. Brooks

1

, and Stephen G. Brooks

1

Abstract

How do concerns about fairness shape foreign policy preferences? In this article, we

show that fairness has two faces—one concerning equity, the other concerning

equality—and that taking both into account can shed light on the structure of

important foreign policy debates. Fielding an original survey on a national sample

of Americans, we show that different types of Americans think about fairness in

different ways, and that these fairness concerns shape foreign policy preferences:

individuals who emphasize equity are far more sensitive to concerns about burden

sharing, are far less likely to support US involvement abroad when other countries

aren’t paying their fair share, and often support systematically different foreign

policies than individuals who emphasize equality. As long as IR scholars focus only on

the equality dimension of fairness, we miss much about how fairness concerns

matter in world politics.

Keywords

public opinion about foreign policy, political psychology, fairness, burden sharing

1

Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA

2

Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Corresponding Author:

Kathleen E. Powers, Dartmouth College, Department of Government 3 Tuck Mall, Hanover, NH 03755,

USA.

Email: [email protected]

Journal of Conflict Resolution

ª The Author(s) 2021

Article reuse guidelines:

sagepub.com/journals-permissions

DOI: 10.1177/00220027211041393

journals.sagepub.com/home/jcr

Article

218 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

From alliance politics to climate change, many of the central challenges in interna-

tional politics today relate to questions of fairness. Superpowers who cont ribute

more to collective defense complain about burden sharing (Oneal 1990), while

rapidly growing economies like China bristle at the prospect of suffering dispropor-

tionate economic harm to protect the global environment. Fairness concerns pervade

territorial disputes (Goddard 2006), peace negotiations (Albin and Druckman 2012),

international cooperation (Kapstein 2008; Kertzer and Rathbun 2015; Efrat and

Newman 2016), and the domestic politics of crisis bargaining (Gottfried and Trager

2016). Among policymakers, fairness appears to be a bipartisan principle:

Democratic Presiden t Obama once declared that “free riders aggravate me” and

warned British Prime Minister David Cameron to “pay your fair share” in military

spending or risk the “special relationship.”

1

A few years later, Republican President

Trump echoed Obama’s concerns that NATO allies’ reliance on U.S. defense spend-

ing was simply “not fair”

2

while also decrying China’s “unfair trade practices.”

3

What makes a foreign policy action “unfair”? We argue that fairness has two

faces. IR scholars tend to discuss fairness primarily in terms of equality—in which

something is fair if everyone receives the same outcome (see, e.g., Baldwin 1993;

Albin and Druckman 2012; Kertzer and Rathbun 2015; Gottfried and Trager 2016).

This is consistent with a voluminous body of research on the ultimatum game, which

finds that players often reject offers that deviate from a 50-50 resource division

because unequal allocations are perceived as unfair (Gu

¨

th, Schmittberger, and

Schwarze 1982). The IR literature on relative gains reaches similar conclusions,

finding that actors dislike agreements that cause them to gain less than the other

side (Grieco 1988; Mutz and Kim 2017).

Yet equality is not the only criterion used to judge what’s “fair”—many actors are

also motivated to maintain equity. Equity implies that differential rewards are fair if

they are proportional to actors’ relative contributions (Adams 1965). Capturing this

distinction is especially important given ideological divides in American politics.

Although most Americans report a commitment to fairness in the abstract (Graham,

Haidt, and Nosek 2009), they disagree on what fairness looks like in practice, with

liberals expressing more concern about equality than conservatives, for example

(Haidt 2012; DeScioli et al. 2014; Jost, Federico, and Napier 2009; Meegan

2019). As Hochschild (1981) and Fiske and Tetlock (1997, 276) note, the tension

between these two fairness conceptions animates many of the key debates in

American political culture. Yet apart from research on inequity aversion in interna-

tional political economy (IPE; Lu

¨

, Scheve, and Slaughter 2012; Bechtel, Hainmuel-

ler, and Margalit 2017), IR scholars who invoke fairness have almost exclusively

focused on equality rather than equity, thereby neglecting fairness’ second face.

In this article, we argue that both equity and equality have important implications

for the study of international politics, and we seek to make three important contri-

butions to research on fairness in foreign policy. First, we introduce a new way to

measure individual differences in equity and equality concerns that we believe will

be useful for future research on fairness in both IR and political science more

2 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 219

generally. Since respondents can have different principles in mind when they report

that fairness matters using standard survey items (Rathbun, Powers, and Anders

2019), we elicit moral judgments about specific equity or equ ality violations in

everyday life. In an original national survey of American adults, we find that the

two faces of fairness form distinct factors: some Americans care about equity, some

care about equality, and some care about both.

Second, we show that the distinction between these two faces of fairness can help

explain debates in the United States about burden sharing. Although burden sharing

is one of the central dilemmas in contemporary foreign policy, looming large in

debates about the future direction of American grand strategy (S. G. Brooks and

Wohlforth 2016), climate policy negotiations (Bernauer, Gampfer, and Kachi 2014),

and global governance more generally, it is strangely understudied in American

public opinion about foreign policy. We show that individual differences in concerns

about equity meaningfully shape Americans’ attitudes about burden sharing in inter-

national politics, and can help explain the bipartisan aversion to disproportionate

U.S. contributions. These findings are consistent with bottom-up theories of public

opinion about foreign policy, offering another example of how personal values spill

over into the foreign policy domain (Rathbun et al. 2016; Kertzer and Zeitzoff

2017): the more concerned about equity individuals are in their daily lives, the more

they are bothered by burden sharing imbalances in foreign policy.

Finally, we turn to a broader selection of foreign policy issues. We show that

equality concerns are associated with support for policies that advance joint gains,

and equity concerns are associated with support for policies that maximize relative

gains. As a result, the effects of each face of fairness on foreign policy preferences

sometimes diverge: equality predicts support for free trade, for example, while

equity predicts support for protectionism, and these results hold even when control-

ling for partisanship or political ideology. Together, our results demonstrate that as

long as IR scholars primarily focus on a single equality dimension of fairness, and

associate fairness exclusively with prosociality, we miss much about how fairness

concerns shape foreign policy.

What’s Fair in Foreign Policy?

One of the central puzzles in the study of public opinion about foreign policy is how

the mass public comes to form its judgments about foreign policy issues, despite

knowing relatively little about international politics. The political science literature

on this subject has largely fallen into two camps. Some scholars offer top-down

models, in which members of the public overcome their uncertainty about foreign

policy issues by taking cues from trusted political elites, usually the leaders of their

preferred political party (e.g., Berinsky 2009; Baum and Potter 2015; Guisinger and

Saunders 2017). Others offer bottom-up models, in which members of the public

overcome their uncertainty about foreign policy issues by drawing on their basic

value systems or orientations (e.g., Hurwitz and Peffley 1987; Goren et al. 2016;

Powers et al. 3

220 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

Kertzer and Zeitzoff 2017). Unlike in top-down models, which assume citizens are

partisan but not ideological, bottom-up models argue that citizens have more

structured poli cy preferences than cynics suggest, because the same values that

shape our behavior in our pe rsonal lives als o shape our forei gn policy preferences

(Rathbun et al. 2016). People who care about retribution, for example, are more

likely to support punitive wars (Liberman 2006) and oppose unconditional finan-

cial bailouts (Rathbun, Powers, and Anders 2019). The value commitments that

predict our lifestyle choices or consumption behaviors also predict our foreign

policy preferences (Cohrs et al. 2005; Kertzer et al. 2014; Bayram 2015; Kreps

and Maxey 2018).

One value that occupies a prominent place in this literature—and in the psychol-

ogy of morality more generally—is fairness (e.g., Graham, Haidt, and Nosek 2009;

Rai and Fiske 2011; Meegan 2019). Concerns about fairness are usually seen as

having evolutionary origins: people must be able to detect and punish cheaters if

they want to enjoy the spoils from cooperation and guard themselves against exploi-

tatio n (Hai dt 2012), and fairness concerns typically begin to appear in children

around the age of five (Fehr, Bernhard, and Rockenbach 2008). Political scientists

have thus linked fairness concerns to a range of phenomena in international politics,

including crisis bargaining (Gottfried and Trager 2016), post-war peace negotiations

(Albin and Druckman 2012), diplomacy (Kertzer and Rathbun 2015), international

humanitarian law (Chu 2019), international cooperation (Efrat and Newman 2016),

and foreign direct investment (Chilton, Milner, and Tingley 2020).

What IR scholars have neglected, however, is that “fairness” carries multiple

meanings, based on different moral principles (Hochschild 1981; Rasinski 1987;

Jennings 1991; Trump 2018; Brutger and Rathbun 2020). While there are debates in

both normative and empirical research about the number of distinct allocation prin-

ciples (Deutsch 1975; Scott et al. 2001), for our purposes we follow Rasinski (1987)

in focusing on two principles in particular: equality and equity.

Equality implies a concern with egalitarian outcomes: an agreement or distribu-

tion is fair when actors attain equivalent end-states. Behavioral economic games

routine ly find that participants prefer resources to be distributed equally among

players (e.g., Gu

¨

th, Schmittberger, and Schwarze 1982; Thaler 1988; Fehr and

Schmidt 1999). In ultimatum games where initial endowments are fixed by the

experimenter, for example, receivers usually “put their money where their mouth

is” and reject unequal offers from proposers (Camerer 1997, 169), choosing to

receive nothing at all rather than accept less than 50 percent of the pot.

4

Other

research illustrates that equality-minded individuals support policies that promote

symmetric outcomes without regard to whether some beneficiaries contribute more

resources than others. In American politics, for example, concerns about equality

tend to be linked with support for social programs like welfare (Feldman and Zaller

1992). The same pattern applies in an IR context: If the purpose of an alliance is to

ensure equal security for all parties, the “fairest” arrangement might require wealthy

members like the U.S. to spend more than their poorer allies.

4 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 221

Equity, in contrast, shifts the focus from outcomes to inputs. Equity implies a

concern with proportionality: resource allocations should account for beneficiaries’

perceived contributions (Rai and Fiske 2011). Individuals who value equity believe

that people ought to reap what they sow.

5

The actor who contributes more to a

common resource merits a bigger slice of the pie: according to the equity principle,

actors’ payoffs should be proportionate to their effort (Adams 1965; DeScioli et al.

2014). Inequity occurs when individuals share a resource but some beneficiaries

shoulder more of a burden for supplying it. Demands that welfare recipients work to

receive benefits often invoke equity principles, for example, and research on

free-riding demonstrates that equity violations plague social dilemmas (Ostrom

1998). Fuhrmann (2020) describes how weaker states in an alliance have incentives

to free-ride because they can benefit from collective deterrence while powerful allies

like the U.S. pay the costs. When policymakers protest that it is unfair for some

NATO members to dedicate the requisite 2 percent of their GDP to defense while

others spend less but receive the same security benefits from the alliance, they call

attention to inequity. Free-riding is common, but inequitable.

6

Despite evidence that people evaluate fairness in terms of both equality and

equity, IR scholarship almost exclusively focuses on the former. When Albin

and Druckman (2012), for example, find that “just” civil war settlements are

more durable than their unfair counterparts, they focus on the distributive justice

principle of equality. Former belligerents prefer agreement s that provide equal

rights for citizens of all parties to the agreement alongside equal political power.

Efrat and Newman (2016) similarly rely on equality when they argue that states

will be more likely to defer child abduction cases to partners whose legal

systems are fair. In public opinion, Kertzer et al. (2014), Kreps and Maxey

(2018), and Cram et al. (2018) similarly define fairness in terms of equal treatment

for individuals.

Equality’s privileged place in research on fairness in IR is significant for several

reasons.

7

First, we know that equity and equality tend to dominate in different

domains in domestic politics—equality reigns in the family, but equity in the mar-

ketplace, for example (Hochschild 1981; Jennings 1991), such that splitting food

equally tend s to be considered fair, while splitting money equally regardless of

contribution is not (DeVoe and Iyengar 2010). But we have little sense of when

each principle dominates in the foreign policy realm.

Second, those few IR scholars who do study equity tend to treat equity prefer-

ences as a constant, rather a variable. Scholarship on inequity aversion in IPE

assumes that everyone bristles at inequity ( Lu

¨

, Scheve, and Slaughter 2012;

Bechtel, Hainmueller, and Margalit 2017). Yet an ever-growing body of psychology

research tells us that people vary in their commitment to moral principles (Graham,

Haidt, and Nosek 2009). Consistent with research on the role of equality in foreign

policy public opinion (Kertzer et al. 2014), we can treat equity concerns as an

individual difference, asking not just whether equity matters, but for whom. Like

the business-minded leaders in Fuhrmann’s (2020) research on free-riding, some

Powers et al. 5

222 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

members of the public might be especially sensitive to imbalances between inputs

and outcomes.

Third, and related, research in social psychology shows that liberals value equal-

ity more than their conservative counterparts (Haidt 2012; Starmans, Sheskin, and

Bloom 2017; Meindl, Iyer, and Graham 2019). When conservatives invoke fairness

in domestic politics, they tend to be concerned primarily with whether those who

work hard or pay more taxes reap appropriate rewards, whereas liberals emphasize

both equity and equality, hoping to advance societal well-being by meeting every-

one’s basic needs. This distinction illuminates partisan differences about welfare

work requirements, for example, but also clarifies important areas of convergence

such as the widespread support for social security across the ideological spectrum:

working Americans all “pay in” but the program provides some financial stability

for all citizens (Haidt 2013; Meegan 2019). Disaggregating fairness also enriches

our u nderstanding of how fairness s hapes foreign policy attitudes. If equality is

primarily a liberal value, but equity matters to Americans across the ideological

spectrum, we can make sense of the cross-partisan nature of complaints about

free-riding in U.S. foreign policy. Moreover, psychologists have also found gender

differences in fairness preferences: whether due to structural societal differences or

early childhood socialization, women often display stronger preferences for equality

than men do (Rasinski 1987; Scott et al. 2001). If fairness attitudes are correlated

with distinctive foreign policy preferences, the tension between these competing

fairness principles could explain part of the gender gap in public opinion about

foreign affairs (D. J. B rooks and Valentino 2011; Mansfield, Mutz, and Silver

2015; Eichenberg and Stoll 2012; Lizotte 2019).

Our initial goal, then, is to replicate existing findings in the psychological liter-

ature with additional evidence that different types of Americans think about fairness

in different ways: to demonstrate that equity and equality are distinct moral princi-

ples, and to map constituencies that support each face of fairness. These considera-

tions lead to our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Fairness has two faces, with equality and equity forming distinct

dimensions.

Support for Hypothesis 1 would largely confirm previous work, though we intro-

duce a new way to measure individual differences in these distinct dimensions of

fairness. But we further claim that both faces of fairness matter for foreign policy

preferences in different ways. IR scholars often portray fairness as a prosocial value

that inspires international cooperation by promoting positive reciprocity (Kertzer

et al. 2014; Kertzer and Rathbun 2015), but this expectation only holds if we limit

our understanding of fairness to equality. Because equality-minded Americans prior-

itize outcomes, they are inclined toward foreign policies that maximize jointly

enjoyed gains and improve global conditions. In pursuit of parity, they set aside

egoistic concerns about the U.S.’s return on their foreign policy investments—like

6 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 223

whether the U.S. gains more relative to other states or contributes more resources

than its partners in pursuit of just, egalitarian ends.

8

The U.S. can contribute to

egalitarian outcomes by working through international institutions like the UN,

providing foreign aid to developing countries, or helping to clean up the g lobal

environment so that everyone has equal access to clean air. Each policy is compa-

tible with an equality principle: The fact that the U.S. might be required to contribute

more to institutions, aid, or environmental protectio n than other states d oes not

undermine fairness when it is defined as equality. This logic explains why previous

research reports a relationship between fairness values and cooperative internation-

alism (Kertzer et al. 2014), or between equality-oriented predispositions like Social

Dominance Orientation and support for trade agreements that maximize joint rather

than relative gains (Mutz and Kim 2017).

By contrast, equity-oriented individuals attend to the cost side of the equation.

Just as research on retribution demonstrates how concerns about justice can lead to

aggression (Liberman 2006; Rathbun and Stein 2020), we argue that equity-minded

Americans will oppose international cooperation on the basis of fairness. Equity

does not imply prosociality. An equity principle demands that actors receive rewards

that reflect their relative contributions, a situation that rarely obtains when the U.S.

responds to distant global problems.

We therefore expect that compared to equality, equity concerns will be strongly

associated with negative evaluations of burden sharing problems in international

politics in particular, and with opposition to policies that do not strike a balance

between the price the U.S. pays and the direct benefits it receives in general. Insofar

as concerns about free-riding dominate debates about everything from NATO con-

tributions to humanitarian interventions, financial bailouts, and climate change

negotiations, we miss out on important dynamics in world politics if we measure

only one face of fairness. Moreover, when a policy promi ses global or indirec t

benefits at a high cost to the U.S., the two faces of fairness will diverge—equality

will be associated with support whereas equity will be associated with opposition.

Together, these theoretical insights lead to two additional hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: Equity is associated with concerns about burden sharing in

foreign policy.

Hypothesis 3: Equality is associated with support for policies that maximize

jointly enjoyed gains, while equity is associated with support for policies that

maximize relative gains.

Methods and Results

To demonstrate the value of studying both faces of fairness in IR, we conducted an

original survey in August 2014 on a national sample of 1,073 Americans recruited

through Survey Sampling International (SSI). Participants, 69.5 percent of whom

identified as white and 51.3 percent of whom identified as female, ranged in age

Powers et al. 7

224 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

from 19 to 95 (median: 49) and reported a median household income of $50 to

60,000. SSI employs an opt-in method to recruit a panel of participants targeted to

census quotas for sex, age, race, and region; Table 1 in Online Appendix §1.2 shows

the sample matches census targets on key demographic characteristics.

9

We present our analysis in three stages. First, we introduce our measurement

strategy to show that Americans differentiate between equity and equality when they

make judgments about right and wrong, and that Americans from both ends of the

political sp ectrum value equity. Second, we show that variations in Americans’

equity commitments can help explain the polarized debates in the United States

about burden sharing in American foreign policy. Third, we analyze a series of

Table 1. Fairness Vignettes: To What Extent Does Each Scenario Feel Morally Wrong?

Violates Factor loadings

Scenario Equity Equality Mean (SD) PA1 PA2

1 A student copies another student’s work on

an ungraded assignment. (Copies Ungraded)

Y N 5.69 (1.54) 0.679

2 A student copies another student’s work and

gets the same grade. (Copies Graded)

Y N 6.12 (1.33) 0.862

3 A runner takes a shortcut on the course

during a marathon. (Marathon Shortcut)

Y N 6.09 (1.36) 0.829

4 Two brothers win the lottery with a ticket

they bought together, but the earnings

aren’t divided evenly. (Lottery Division)

Y Y 5.75 (1.57) 0.566 0.212

5 A girl takes all of the Halloween candy from

a bowl, leaving none for others.

(Halloween Candy)

Y Y 5.76 (1.49) 0.653 0.17

6 A raise is given to a worker, when another

worker needs it more. (Raise for One

Worker)

N Y 3.71 (1.9) 0.83

7 An employee earns a lot of money while

another earns very little. (Employee

Earns More)

N Y 4.10 (1.96) 0.812

Note: All items range from 1 to 7, with higher values indicating that the situation feels more morally

wrong. The second and third columns indicate whether the scenario involves an equity violation (in which

the outcome is not proportional to the inputs), an equality violation (in which the outcomes are

inegalitarian), or both; the first three scenarios violate equity but not equality, the last two scenarios

violate equality but not equity, and two scenarios (Lottery Division and Halloween Candy) violate both. The

table shows two key findings. First, scenarios that include an equity violation are seen as substantially

more morally wrong than scenarios that do not, showcasing the importance of equity in our moral

judgments. Second, the results from an exploratory factor analysis show that a two-factor solution maps

onto our theoretical codings, with one factor referring to equity, and the other to equality. Interestingly,

the two scenarios that include both equity and equality violations show some weak cross-loading, but

ultimately load on the equity factor rather than the equality factor, suggesting that the equity concerns are

more salient.

8 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 225

broader foreign policy issues to show that the effects of equity and equality some-

times diverge, with concerns about equality associated with support for policies that

maximize global gains, and concerns about equity associated with policies that

maximize relative gains. These results highlight why scholars need to consider both

faces of fairness in research on public opinion in foreign policy.

Differentiating between Two Faces of Fairness

Although political scientists sometimes use the Moral Foundations Questionnaire

(MFQ) to study the extent to which individuals care about people being “treated

fairly” (Graham, Haidt, and Nosek 2009), our purposes preclude this and similar

scales because the meaning of “fairness” here is itself ambiguous: participants could

interpret “fair” treatment as equity, equality, or both—leaving us uncertain of which

construct we are measuring (Rathbun, Powers, and Anders 2019; Brutger and Rath-

bun 2020). A key goal of this paper is to develop an alternative measurement scale

that can usefully distinguish between equity and equality for future political science

research.

We therefore build on Clifford et al. (2015, 1179), which develops a series of

“moral foundations vignettes” to assess individuals’ moral co mmitments. Each

vignette describes a situation in which an actor violates some moral principle, and

asks respondents to evaluate whether the action feels morally wrong. The vignettes

are designed both to depict violations of one value at a time, such that ideal items

will discriminate between even closely related moral principles, and to distinguish

moral violations from social norms. For example, the fairness vignettes avoid refer-

ences to (1) physical or emotional harm, which taps the harm/care foundation,

(2) hierarchical relationships, lest they invoke authority values, and (3) “race, gen-

der, or structural equality” because these characteristics are more likely to tap other,

non-moral, attitudes (Clifford et al. 2015, 1181).

10

Clifford et al. (2015, 1179) note

that the moral foundations scale “relies on respondents’ rating of abstract principles,

rather than judgment of concrete scenarios,” and that abstract endorsements may not

always translate into political attitudes. The vignettes allow us to probe concrete

moral judgments, but in scenarios taken from everyday life, rather than politics or

foreign policy.

Table 1 displays the seven vignettes we employ to measure fairness attitudes,

building on the fairness inventories established by Clifford et al. (2015), Iyer (2010),

and Meindl, Iyer, and Graham (2019). For each vignette, participants indicated the

extent to which the situation felt morally wrong on a seven-point scale from “not at

all wrong” to “extremely wrong.” The first three vignettes in Table 1 depict clear

equity violations, where individuals receive outcomes that are not proportionate to

the inputs they provide. For example, “A student copies another student’s work and

gets the same grade,” or “A runner takes a shortcut on the course during a marathon”

both describe outcomes that do not accurately correspond to individuals’ contribu-

tions. These scenarios are not problematic on equality principles (we don’t care

Powers et al. 9

226 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

about guaranteeing equality of outcomes when evaluating assignments, or on a race

course) but are problematic on equity principles (we expect that individuals who

perform better will be rewarded as such).

The last two vignettes capture clear equality violations, where actors fail to attain

equivalent end-states. It might be considered fair from an equity perspective when

“An employee earns a lot of money while another earns very little” (since under

equity principles, earnings can be guided by merit), but this asymmetry in wages is

considered unfair from an equality perspective (Meindl, Iyer, and Graham 2019).

Finally , two of the vig nettes depict a violation both of equity principles and of

equality principles. In the lottery division scenario (“Two brothers win the lottery

with a ticket they bought together, but the earnings aren’t divided evenly”), the

uneven division of the winnings not only represents an equality violation, but also

an equity violation, since the two brothers bought the ticket together. In the hallow-

een candy scenario (“A girl takes all of the halloween candy from a bowl, leaving

none for others”), the girl who absconds with the candy not only fails to split it

evenly with others (an equality violation), but given the lack of information indi-

cating she was the one who provided all of the candy in the first place, likely takes a

haul that is disproportionate to her contributions (an equity violation).

Two additional points are worth noting about Table 1. First, the table presents

basic descriptive statistics for each vignette. Although the means for most of the

items are relatively high—consistent with extensive research showing that fairness is

an important moral principle for most Americans (Graham, Haidt, and Nosek 2009;

Haidt 2013)—some are substantially higher than others: scenarios that include an

equity violation are seen by our respondents as more morally wrong than scenarios

that do not, showcasing the importance of equity in our moral judgments.

Second, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on the fairness vign-

ettes. If fairness is unidimensional—if moral judgments about fairness violations

depend on a single principle—we would find that one factor explains most of the

common variance in the data. Instead, parallel analysis and model fit statistics

suggest a two factor solution, which fits the data well (TLI¼0:93, RMSEA¼0:09).

11

We therefore estimate a two factor solution using principal axis factor analysis with

oblimin rotation, producing the factor loadings in the two right-hand columns of

Table 1. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, the results show that the first three vignettes,

which violate equity principles, load on a single factor; the last two items, which

violate equality principles, load on the other factor. And, of particular interest, the

two items that feature both equity and equality violations cross-load on both factors,

but ultimately display stronger loadings on the equity factor than the equality factor.

This finding suggests that respondents confronted with bo th equity and equal ity

violations found the equity concerns in these scenarios to be more salient, and

reinforces the importance of taking fairness’ second face into account.

To obtain respondent-level measures for sensitivity to different types of fairness

concerns, we extract factor scores from the factor analysis and produce latent mea-

sures for concerns about equity (mean ¼ 0:82, sd ¼ 0:19) and concerns about

10 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 227

equality (mean ¼ 0:5, sd ¼ 0:26).

12

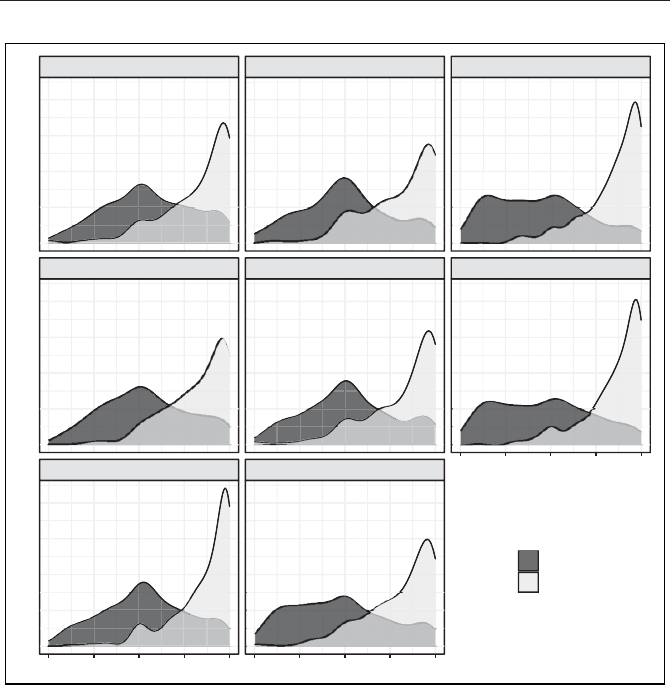

Figure 1 displays the density distributions for

equity and equality across partisan and ideological categories. What is striking is just

how widespread concerns about equity are. For each constituency, equity trumps

equality, and the results are also relatively stable across partisan and ideological

subgroups: conservatives value equity more than liberals do (t ¼�2:54, p < 0:05),

but the substantive size of the difference is relatively small.

13

In contrast, we find

both ideological and partisan divides on equality: Democrats care more about

outcome-oriented equality violations than their Republican counterparts (t ¼ 6:8,

p < 0:01), and liberals more than conservatives (t ¼ 3:85, p < 0:01). This pattern is

consistent with what psychologists recognize as a key line dividing ideas about

Female Male

Liberal Moderate Conservative

Democrat Independent Republican

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00

Density

Fairness type

Equality

Equity

Figure 1. Strong concerns about equity across demographic groups.

Note: Figure 1 displays density distributions for equity and equality across party identification, ideology,

and gender. The plots show that both the left and right value equity, whereas left-leaning respondents

place a heavier emphasis on equality than right-leaning ones do. Women care more about both types of

fairness than men do.

Powers et al. 11

228 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

fairness in American politics (Haidt 2013; Clifford et al. 2015; Meegan 2019).

Multiple group factor analysis in Online Appendix §2.3 further confirms that Dem-

ocrats and Republicans think about fairness in slightly different ways: although we

obtain the same factor solution in both groups, we also find that the two latent factors

are moderately correlated among Democrats (r ¼ 0:30), but not among Republicans

(r ¼ 0:01): Democrats who care more about equity tend to also care more about

equality, but the same is not true for their Republican counterparts.

Finally, we find even starker differences with respect to gender. Women care

significantly more about fairness violations than men do, both for equity (t ¼ 4:439,

p < 0:01) and equality (t ¼ 4:22, p < 0:01). These patterns highlight the cost of

privileging equality in research on fairness in IR. Equality alone cannot capture how

Americans think about fairness and in fact, appears to be a significantly weaker

concern than equity, even among liberals. Next, we examine how these different

types of fairness concerns are associated with foreign policy preferences.

Equity Predicts Opposition to Burden Sharing Violations

Our initial findings show that most Americans value equity. We therefore turn to a

specific class of foreign policy issues where we expect this type of moral principle to

loom particularly large: burden sharing. Despite the fact that burden sharing con-

cerns animate contemporary debates about the most consequential foreign policy

issues from NATO to the Paris Climate Agreement, they are rarely included in

standard measures of foreign policy attitudes (e.g., Hurwitz and Peffley 1987;

Chittick, Billingsley, and Travis 1995; Rathbun et al. 2016; Gravelle, Reifler, and

Scotto 2017). We argue that when members of the public decry actions in which the

U.S. bears disproportionately large costs, they transfer their general concern for

equity in their daily lives to the foreign policy domain.

Our four dependent variable questions solicit individual reactions to common

scenarios in which the U.S. makes a substantial contribution to resolve a collective

problem. Participants responded to four hypothetical foreign engagements and rated

the extent to which each poses a problem for the U.S. on a scale from 1 (“not a

problem at all”) to 7 (“a very big problem”). Each item, listed in Table 2, describes a

different substantive domain in which the U.S. plays a dominant role in resolving a

collective problem. Defense Budgets, for example, implicates U.S. allies who ear-

mark fewer resources for defense, while Enviro nment introduces a hypothetical

scenario in which the U.S. foots the bill for an environmental disaster in international

waters. The scenarios each highlight the concerns about proportionality that plague

foreign policy questions across issue areas. In creating the four scenarios, we aim to

capture a set of problems that implicate equity and demonstrate its important role in

foreign policy public opinion. We turn to a broader set of foreign policy problems

that implicate both equity and equality in a subsequent section below.

In addition to factor scores for equity and equality, our primary independent

variables, we control for three widely-used scales for foreign policy

12 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 229

orientations—militant internationalism, cooperative internationalism, and isolation-

ism (Wittkopf 1990). Militant internationalism (MI) refers to an inclination to use

force to achieve foreign policy goals, and emphasizes the importance of demonstrat-

ing military resolve. This measure of military assertiveness thus taps the familiar

distinction between foreign policy hawks and doves. Cooperative internationalism

(CI) captures the extent to which individuals want the U.S. to work with other states

and international institutions to solve global problems like climate change (Wittkopf

1990). It entails a commitment to global participation but not to military force. For

isolationism, we include a scale that taps this general preference for disengagement

from the world—a stance that maintains that America should “come home” and

scale down its conception of itself as a leader (Chittick, Billingsley, and Travis

1995).

Finally, we included a battery of demographic questions alongside measures of

partisanship and ideology. Participants report their age, sex, race, education attain-

ment (from less than high school to Post-graduate), income (split into quartiles for

analysis), and U.S. region of residence (midwest, northeast, south, or west). We

measure self-reported partisanship with a seven-point scale where a 7 indicates

strong Republican, and ideology on a seven-point scale from extremely liberal to

extremely conservative. The fairness vignettes, burden sharing violations, foreign

policy orientations, and demographics appeared in separate, randomly ordered

blocks.

Table 3 presents estimates from a series of OLS regression models that predict

responses to the four burden sharing vignettes. The dependent measures and con-

tinuous independent variables have been rescaled from 0 to 1, and higher values

indicate that participants rated the scenario a bigger problem for the United States.

Positive coefficients suggest that stronger commitments to the moral principle are

associated with less support for America taking on an “unfair” global burden. Mod-

els 2, 4, 6, and 8 include foreign policy orientations and demographic controls.

Consistent with H2, equity is a statistically and substantively important predictor

of attitudes toward U.S. contributions to global problems. The extent to which

Table 2. Burden Sharing Scenarios: How Much of a Problem Is Each for the United States?

Countries such as Germany, Canada, and Japan devote a far smaller share of their economy to

defense spending than the United States does, because they are US allies and America has

pledged to defend them. (Defense Budgets)

Western allies give less foreign aid to provide for education and health care for women and

children in the Middle East, because they know the US will foot the bill. (Foreign Aid)

The US provides all of the needed troops and money for a peacekeeping mission while other

countries do not contribute any troops or money to the mission. (Peacekeeping)

The US provides all of the needed resources and personnel for cleaning up toxic waste

contamination from a sunken ship in Antarctica while other countries do not contribute

any resources or personnel to the effort. (Environment)

Powers et al. 13

230 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

Table 3. Americans High in Equity Preferences Tend to be More Concerned about Burden Sharing Violations in US Foreign Policy.

Domain of Burden sharing Violation:

Defense Budgets Peacekeeping Environment Foreign Aid

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

Equity 0.325*** 0.281*** 0.469*** 0.376*** 0.453*** 0.396*** 0.468*** 0.384***

(0.044) (0.047) (0.041) (0.043) (0.041) (0.044) (0.041) (0.044)

Equality 0.119*** 0.119*** 0.007 0.010 0.054* 0.058* 0.022 0.029

(0.033) (0.035) (0.030) (0.032) (0.030) (0.032) (0.031) (0.032)

Cooperative Int. 0.076 0.032 0.053 0.012

(0.046) (0.042) (0.043) (0.043)

Militant Int. 0.049 0.022 0.066 0.118***

(0.047) (0.042) (0.043) (0.043)

Isolationism 0.175*** 0.172*** 0.154*** 0.169***

(0.039) (0.035) (0.036) (0.036)

Male 0.023 0.038** 0.027* 0.027*

(0.017) (0.016) (0.016) (0.016)

White 0.002 0.015 0.017 0.037*

(0.021) (0.019) (0.020) (0.020)

Age 0.001** 0.003*** 0.001*** 0.002***

(0.001) (0.001) (0.001) (0.001)

Some College 0.011 0.019 0.023 0.026

(0.024) (0.022) (0.022) (0.023)

College 0.011 0.019 0.003 0.021

(0.023) (0.021) (0.021) (0.021)

Post-Graduate 0.007 0.012 0.011 0.004

(0.031) (0.028) (0.028) (0.029)

Income: $30–60,000 0.009 0.004 0.001 0.009

(continued)

14

Powers et al. 231

Table 3. (continued)

Domain of Burden sharing Violation:

Defense Budgets Peacekeeping Environment Foreign Aid

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

(0.022) (0.020) (0.020) (0.020)

Income: $60–100,000 0.005 0.005 0.008 0.010

(0.023) (0.021) (0.021) (0.021)

Income: > $100,000 0.026 0.003 0.003 0.017

(0.026) (0.024) (0.024) (0.024)

Region Controls PP P PPPPP

Constant 0.317*** 0.203*** 0.361*** 0.222*** 0.298*** 0.161*** 0.324*** 0.082

(0.038) (0.066) (0.035) (0.060) (0.035) (0.061) (0.035) (0.061)

N 1,002 997 1,002 997 1,002 997 1,001 996

R

2

0.075 0.109 0.121 0.181 0.123 0.163 0.121 0.171

Note: Table displays OLS coefficients, standard errors in parentheses. Higher values indicate participants rated the scenario a bigger problem for the US. All continuous

variables, except age, have been rescaled from 0 to 1. Reference categories are <$30,000, High school or less, and West.

*p < .1.

**p < .05.

***p < .01.

15

232 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

individuals believe that input/output ratios dictate whether an action should be

deemed moral or immoral predicts their view of whether certain foreign policy

activities are justifiable. Indeed, the environment, foreign aid, and peacekeep ing

vignettes draw almost exclusively on equity concerns—not equality. In the case

of environmental cleanup in Antarctica, a move from the minimum to the maximum

on equity is associated with a 0.453-unit increase in the policy preferences—a shift

in nearly half the 0 to 1 scale. Since Antarctica does not belong to just one state, the

cleanup arguably benefits all global actors. Like President George W. Bush, who

avowed that he would not “let the United States carry the burden for cleaning up the

world’s air,” equity-minded citizens think that other states should contribute if they

expect to reap the rewards from a clean environment.

14

The same logic underlies the strong association between equity and foreign aid.

Because allies know that the U.S. will provide long run development benefits

abroad, they shirk the opportunity to contribute a share proportionate to their GDP

or relative interest in the positive externalities associated with advancing women’s

healthcare. As participants’ moral commitment to equity increases, so does their

disdain for this foreign aid arrangement (b ¼ 0:468, p < 0:01). Peacekeeping mis-

sions have similarly concentrated benefits, such that equity values predict negative

perceptions of America taking the primary role in bearing the costs. A two standard

deviation increase in equity (sd ¼ 0:19) is associated with a 0.18-unit increase in

judgments that it is a problem for the U.S. if other states to not contribute to a

mission.

In contrast, equality plays a relatively smaller role: The coefficient for equality is

statistically significan t in Model 5—the environment vignett e (p < 0:1), but the

effect is substantively small. A move from the minimum to the maximum predicts

a 0.054 increase in the dependent measure, just a fraction of a step on the seven-point

scale. This is striking given the attention paid to fairness as primarily a value that

promotes individual rights in both political science scholarship (Jost, Federico, and

Napier 2009) and psychological research on moral foundations (Graham, Haidt, and

Nosek 2009).

Only burden sharing in security alliances—Models 1 and 2—seems to draw

significant opposition on the basis of both equity and equality. A move from the

minimum to the maximum on the equity dimension of fairness predicts a 0.325-unit

increase in reporting that disproportionate defense spending is a problem for the

United States. Allies contribute relatively less as a share of their GDP, and yet

benefit greatly from U.S. protection. At the same time, there are disparate outcomes

to consider if the U.S. is not equally secure as a consequence of their alliances. The

positive coefficient on equality bears out this relationship.

Models 2, 4, 6, and 8 include three foreign policy orientations frequently

identified as the main organizing structures for foreign policy attitudes (Gravelle,

Reifler, and Scotto 2017) alongside demographic controls. Of the three orientations,

only isolationism has a consistent and statistically significant relationship with the

dependent variables. Isolationist participants report that it is problematic for the U.S.

16 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 233

to act as the primary contributor to resolving any of the four international problems.

Cooperative and militant internationalism have little bearing on how participants

judge America’s unfair burdens. Importantly, the effects of equity are substantively

larger than isolationism. For example, a shift from the minimum to the maximum on

isolationism predicts a 0.172-unit increase in the assessment that it is a problem for

the U.S. to contribute all resources to peacekeeping mission. In contrast, a shift from

the minimum to maximum on equity is associated with a 0.376-unit increase in the

DV—twice the size of isolationism’s effect.

The results presented in Table 3 demonstrate that Americans who care about

equity express significantly greater concern about foreign policy scenarios in

which the U.S. contributes more than they benefit. This pattern holds across four

diverse policy domains and when we control for a range of foreign policy orien-

tations and demographic variables. The effect of equality, however, is less con-

sistent—the moral commitment to equal outcomes held by many left-leaning

Americans predicts attitudes toward defense spending but not other forms of

cooperation. The fact that equity continues to exert a substantively large effect

on burden sharing attitudes even controlling for foreign policy orientations like

isolationism is important: it shows that there is a class of individuals who are not

necessarily predisposed to want the US to stay home and focus more on its own

problems, but who are aggravated by other countries not pulling their weight.

Moreover, we fielded this study in 2014, well before Donald Trump and the

Republican party began amplifying concerns about “unfair” trade deals and alli-

ance arrangements, suggesting that our results are unlikely to be the artifact of

elite cues.

In Online Appendix §2.1, we conduct a variety of additional robustness checks,

showing that the stronger findings for equity in our results are not due to asymme-

tries in scale length, and that the pattern of results we report here are not merely an

artifact of broader ideological or partisan differences: equity retains its substantively

large and statistically significant effect on burden sharing concerns even when

controlling for partisanship and political ideology. Finally, we test for the possibility

that the fairness vignettes primed participants to adopt an equity lens when they

considered burden sharing violations. We find no evidence for order effects, miti-

gating this concern. Together, these findings offer another example of how personal

values spill over into foreign policy preferences (Rathbun et al. 2016): the more

individuals are offended by equity violations in their daily lives, the more concerned

they are about burden sharing in foreign policy, whether in terms of allies’ defense

budgets or foreign aid, peacekeeping or the environment.

Equity and Equality Shape Foreign Policy Attitudes beyond Burden Sharing

Our results show that equity values—but not equality values—are important for

understanding divergent reactions in the United States toward burden sharing in

foreign policy. Given the extent to which burden sharing issues feature prominently

Powers et al. 17

234 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

in contemporary foreign policy debates, but are somewhat understudied in the aca-

demic literature on public opinion about foreign policy, these findings make an

important contribution. However, one concern about this analysis is that the outcome

variables uniquely implicate equity—the DV question itself makes U.S. costs salient

by asking people whether the situation is a problem for the U.S.—and thereby mask

the important role of equality. In this section, we therefore measure support for a

broader set of concrete foreign policy proposals and probe the conditions under

which the two faces of fairness complement or contradict each other.

We measure support for three policy proposals, each of which implicates a

potential mismatch between U.S. contributions and the policy’s primary benefici-

aries abroad in a different domain of foreign affairs: international political economy,

international cooperation, and defense. The first proposal asks participants whether

they support or oppose decreasing limits on imports of foreign-made products, and

signing more free trade agreements like NAFTA (Free Trade).

15

We expect that

equality will predict support for this proposal, because free trade agreements level

the playing field for foreign companies and economies by allowing them to compete

for American business. Regional trade agreements like NAFTA can produce larger

gains for Mexico than for the U.S., but Americans who value equality view closing

the economic gap between developed and developing states as a desirable end.

16

Our

values shape whether we paint free trade as fair trade. By contrast, equity-minded

Americans might oppose free trade agreements that could damage some sectors of

the U.S. economy and improve trading partners’ overall welfare to a greater extent

than America’s. In turn, equity would predict less support for the Free Trade pro-

posal. Yet others might view competitive markets as inherently equitable, because

free markets enable actors to reap proportionate gains for their work. We consider

these competing expectations for equity in our analysis.

The second proposal asks participants whether they support an arms control treaty

that would reduce both US and Russian nuclear arsenals (Arms Control). We expect

a positive relationship between equality and support for this proposed treaty, which

offers global benefits: the potential for consequential accidents declines alongside

the number of nuclear weapons (Sagan 1995). Equity-minded participants, however,

will attend to the costs associated with arms control. The U.S. and Russia will each

witness a small decrease in their overall power. Some people who value equity might

think that this is a “fair” price to pay for the security the U.S. will gain from a smaller

Russian stockpile. But the proposal lacks information about the U.S. and Russia’s

respective starting positions, which could arouse relative gains concerns among

those who view equal reductions as inequitable—driving opposition. These con-

cerns muddy our expectations about how equity relates to support for arms control.

Finally, we ask participants if they support increasing military spending to allow

the US to better solve international problems (Military Spending). Again, this pro-

posal presents clear global benefits—to the extent that deploying the U.S. military

augurs peace, equality-minded Americans will be eager to invest. Viewed in a

different light, though, the proposal requires the U.S. to invest scarce economic

18 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 235

resources into a program that only benefits national security via indirect routes:

“Solving global problems” can bolster U.S. security in the long run, but the descrip-

tion emphasizes those benefits that accrue to the world. Much like our burden

sharing scenarios, this proposal asks the U.S. to pay while others reap the

rewards—driving equity-based opposition.

Each of these proposals entail ambiguous framing relative to the burden sharing

vignettes. They describe a plan, but leave room for participants to gauge the

distribution of costs and benefits associ ated with implementing the policy. This

ambiguity creates conceptual distance between our independent and dependent

variables and allows us to test out theory’s implications for a broader range of

issues. But it also limits our ability to parse fairness from partisanship if party

identification partly colors which face of fairness a proposal evokes. For example,

Republicans might focus on the equity-reducing prospects for n ew trade agree-

ments, whereas Democrats might look at the same proposal and think of the

implications for global equality. C ontrolling for partisanship cannot account for

this subtler pathway for confounding, whereby partisanship shapes the relative

salience of different policy aspects. Our analysis proceeds w ith this important

caution in mind.

Figure 2 presents estimates from a series of OLS models that estimate the rela-

tionship between equity, equa l ity, and support for each policy proposal. Each

model also controls for militant/cooperative internationalism and isola tionism—

coefficients depicted for comparison—and demographic variables.

17

The results

point to five key conclusions. First, consistent with Hypothesis 3, the two faces of

fairness are not always complementary. Whereas equality values are associated with

more support for military spending and free trade, equity-minded Americans would

rather not sacrifice resources if U.S. contributions outstrip whatever benefits the

U.S. stands to gain. Rather than increase foreign competition for Americans’ busi-

ness, equity-minded Americans prefer to reserve their home market for domestic

producers—perhaps prioritizing market-based equity at home but not beyond U.S.

borders. In the case of an arms control agreement, equality increases support for a

proposal that would limit nuclear arsenals while equity is unrelated to arms control

preferences, mirroring the pattern we observed for 3 of the 4 burden sharing items.

Second, these results underscore our argument that fairness is not inherently

prosocial: equity values discourage international economic agreements, for exam-

ple. Moreover, we find evidence that concerns about equality can increase demands

for military spending. Focused on outcomes, equality-minded respondents see prom-

ise in bolstering the U.S. defense budget if it might help solve international prob-

lems. Defense spending could therefore draw support from a coalition of militant

internationalists and the equality-minded Americans who otherwise eschew hawkish

politics (Maxey 2020).

Third, although research on foreign policy attitudes tends to divorce security from

economics and assume that international trade attitudes follow a different logic than

other foreign policy domains, we find evidence that equity and equality can shape

Powers et al. 19

236 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

public support for NATO and NAFTA alike. This finding complements a growing

body of work on the relationship between values and public opinion about interna-

tional economic policies (Kaltenthaler and Miller 2013; Rathbun 2016; Rathbun,

Powers, and Anders 2019).

Fourth, it illustrates the import ance of studying core values in foreign policy

preferences more generally: even though these foreign policy proposals are arguably

further removed from fairness considerations than the burden sharing vignettes are, a

set of Wald tests find that we experience a significant reduction in model fit when we

drop equity and equality from the two models where we have the strongest theore-

tical expectations (Free Trade and Military Spending), even when controlling for a

wide range of other demographic characteristics and foreign policy orientations.

Indeed, Online Appendix §2.5 shows that the effects of fairness hold when control-

ling for party identification and ideology in turn, despite the important role played by

partisanship in shaping policy preferences. Understanding respondents’ differential

concerns about each face of fairness thus systematically enhances our understanding

of their foreign policy preferences.

Fifth, the proposals that we focus on here each represent policy areas that have

been characterized by pronounced gender gaps: in the United States, women have

historically been less supportive of free trade (Mansfield, Mutz, and Silver 2015;

Guisinger 2016), more supportive of arms control (Silverman and Kumka 1987), and

less supportive of defense spending (Eichenberg and Stoll 2012) than men. Despite

extensive documentation of gender gaps in foreign policy public opinion, “the

reason for these differences remains elusive” (Lizotte 2019, 126). Given the

Arms Control Free Trade Military Spending

-0.5 0.0 0.5 -0.5 0.0 0.5 -0.5 0.0 0.5

Iso

CI

MI

Equity

Equality

Effect size

Figure 2. Equity, equality, and policy proposals. Note: N ¼ 489, 515, 477, respectively. Figures

display OLS coefficient estimates and 95 percent confidence intervals for equality, equity,

militant internationalism (MI), cooperative internationalism (CI) and isolationism from models

that also include additional demographic controls. To facilitate direct comparability, each

variable has been rescaled to range from 0 to 1, and higher values on the DV indicate support

for the policy.

20 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 237

apparent gender differences in fairness commitments, variation in concerns about

equality could be one explanation for these gaps.

Results from the OLS models, presented in Online Appendix §2.4, reveal no

effect of gender on support for the three policy proposals. Our interest does not lie

in the total effect, however, but in whether gender has any indirect effects through

values.

18

We thus estimate a series of nonparametric causal mediation models, in

which the effect of gender on each of these foreign policy issues is mediated by

concerns about each type of fairness, while controlling for a host of demographic

characteristics. Although care should be taken in interpreting these results given

potential confounders, the results suggest that fairness concerns offer one potential

explanation for gender differences in two of the three issues: arms control, and trade

attitudes.

The average causa l mediation effect (ACME) of gender on support for arms

control, through equality, is 0.007 (0.017, 0.00). To the extent that men are less

committed to equality than women, they will in turn be less supportive of arms

control. The ACME is small, but statistically significant. We find similar evidence

for indirect-only mediation on support for free trade. The effect of gender channeled

through equality is significant and negative, accounting for approximately 31.5 per-

cent of the total effect. These results suggest that the gender gap in trade attitudes

may be explained in part through women’s greater commitment to egalitarian out-

comes. We find no evidence that the relationship between gender and support for

these three policy issues is mediated by equity. Importantly, the absence of signif-

icant direct or total effects for gender implies one or more possible suppressors—

other, unmeasured mechanisms that push men toward arms control and free trade

(Rucker et al. 2011). Future research should account for equality values alongside

other relevant factors like partisanship, identity, and other prosocial values to offer a

more complete understanding of gender gaps in foreign policy attitudes.

Conclusion

In this article, we sought to contribute to the study of fairness in IR by reminding IR

scholars that fairness is multidimensional (Adams 1965; Deutsch 1975; Hochschild

1981). Whereas the existing literature on fairness in IR has focused almost exclusively

on fairness as equality, we can also understand fairness as equity. Because personal

values spill over into the foreign policy domain (Rathbun et al. 2016), both faces of

fairness are important for understanding the contours of foreign policy preferences.

Although IR scholars typically associate fairness with cooperation, our results

demonstrate that equity values encourage opposition to security cooperation and

public goods provision across several contexts, due in particular to concerns about

inadequate burden sharing. We therefore find evidence of a new psychological

microfoundation for isolationism, something existing sch olarship has failed to

uncover (Kertzer et al. 2014). Moreover, we fielded o ur survey in 2 014, before

Donald Trump campaigned on inequities in the US alliance system, which suggests

Powers et al. 21

238 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

that our findings are not merely an artifact of partisan cue-taking. Our results offer

further support for the continued importance of core values and moral judgments in

shaping foreign policy preferences (Bayram 2015; Rathbun et al. 2016; Kreps and

Maxey 2018), and in studying fairness concerns as a variable rather than a constant.

And although our findings are consistent with bottom-up theories of public opinion

in foreign policy (Kertzer and Zeitzoff 2017), they also suggest important implica-

tions for theories of elite political behavior. Framing research in American politics

argues that political elites seek to mobilize and persuade voters using appeals that

frame issues in terms of the values that resonate with their audience (Nelson, Claw-

son, and Oxley 1997). The fact that Republicans and Democrats alike value equity

suggest that it should be a particularly potent way to frame foreign policy issues.

We also observe important differences in how Republicans and Democrats think

about equality. Our findings thus contribute to a growing literature on partisanship

and ideology in foreign policy. IR scholars have found that Republicans and Dem-

ocrats tend to conduct systematically different types of foreign policies, not just

because each party’s base has a different set of interests, but because “right parties

have somewhat different values from left parties.” (Palmer, London, and Regan

2004, 1-24; see also Rathbun 2004; Bertoli, Dafoe, and Trager 2019). We observe

differences in how Democrats and Republicans conceptualize fairness—Democrats

place greater value on equality than Republicans do—that suggest a potential micro-

foundation for distinct partisan approaches to foreign policy.

Our findings also relate to research on partisan or ideological differences in moral

reasoning generally (Graham, Haidt, and Nosek 2009). Indeed, although our analysis

focused on the two faces of fairness in foreign policy, it also informs research on

public opinion about domestic issues—since the equity and equality scales can be

fruitfully applied in other contexts. As Hochschild (1981) noted nearly four decades

ago, many key debates in American political life involve competing conceptions of

fairness. Understanding individual differences in equity- and equality-based moral

judgments can therefore enrich our understanding of public opinion more broadly.

Acknowledgment

We thank Scott Clifford, Jeff Friedman, Chris Gelpi, Ravi Iyer, Rose McDermott, Chris Ray,

Julie Rose, Drew Rosenberg, and audiences at the 2017 ISA meeting and 2020 Grand Strategy

Conference at Ohio State’s Mershon Center for helpful feedback and discussions, and Chelsea

Lim and Felicia Jia for excellent research assistance.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, author-

ship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of

this article.

22 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 239

ORCID iD

Joshua D. Kertzer https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7358-0638

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Notes

1. Barack Obama, quoted in Jeffrey Goldberg, April 2016, “The Obama Doctrine,” The

Atlantic.

2. Donald J. Trump. Twitter Post. July 9, 2018. 7:55 a.m. https://twitter.com/realDonald

Trump/status/1016289620596789248

3. Donald J. Trump, “President Donald J. Trump is Confronting China’s Unfair Trade

Policies,” The White House.

4. We use inequality to describe circumstances where group members receive dispara te

benefits, irrespective of contributions. “Inequity” exists when resource allocations are

not proportionate to relative contributions from beneficiaries. This distinction highlights

one potential source of confusion that arises from importing behavioral economics to IR:

scholars sometimes use “inequity aversion” to describe concerns about both inequity and

inequality, and test economic models of inequity aversion by assessing how participants

“respond to inequalities” (Wilson 2011, 208). The standard structure of laboratory eco-

nomic games contributes to this issue. A participant playing an ultimatum game often

lacks information about whether she or her partner has contributed more to the resource

endowment. Without a metric to determine the equitable input/outcome ratio, “the equi-

table outcome, is given by the egalitarian outcome” (Fehr and Schmidt 1999, 822).

Incorporating e arned endowments into lab experiments decreases the share of 50 -50

splits, suggesting that many games overestimate the prevalence of inequality aversion.

We avoid this complication by only using the terms equity and inequity in contexts where

relative contributions are known and relevant.

5. As Fiske and Tetlock (1997, 276), note, each face of fairness stems from a different

“relational model”: Equality constitutes fairness in Equality Matching relationships,

which are predicated on in-kind reciprocity and common among peers or co-workers.

Fairness as equity marks Market Pricing relations, where people interact according to a

principle of proportionality. See also Powers (2022) for a discussion of relational models

in IR.

6. Although equity concerns can draw on objective metrics—an investor will earn part of

the company’s profits in proportion to what she invests—subjective perceptions often

shape judgments (e.g., Trump 2020).

7. In addition to work on inequity aversion, which we describe below, the only other work

on equity in IR we are aware of is Gottfried and Trager (2016), which draws on equity

theory when presenting its theoretical model. Consistent with much of the behavioral

economic tradition more generally (see, e.g., Fehr and Schmidt 1999), however, it uses an

experimental protocol in which neither party has an unambiguous claim to a larger share

Powers et al. 23

240 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)

of the disputed object (Gottfried and Trager 2016, 253). It therefore cannot distinguish

between effects from concerns about equity versus equality.

8. Although people who conceive of justice in terms of equality are more likely to endorse

separate other-regarding moral beliefs (Graham, Haidt, and Nosek 2009), equality is not a

proxy for general prosociality. Research from the moral foundations tradition shows that

the fairness and harm/care foundations co-vary—but they remain empirically and con-

ceptually distinct moral systems (Haidt 2012). Equality, like equity, taps beliefs about

justice (Meindl, Iyer, and Graham 2019), whereas harm/care refers to individuals’ con-

cerns about others’ suffering. Caring taps compassion, not fairness.

9. The sample closely matches the U.S. population on key variables including sex, age, race,

and region. Highly educated Americans are slightly over-represented in our sample. In

the Online Appendix, we show that our substantive conclusions hold when we reweight

the data to more closely match population parameters for educational attainment.

10. See Online Appendix §1.3 for a broader discussion of scale construction.

11. Moreover, the first and second factors have eigenvalues of 2.75 and 0.77, whereas the

third factor drops to 0.11.

12. Both are rescaled from 0 to 1 in the analysis below for ease of interpretability.

13. Importantly, these differences in equity are ideological rather than partisan—Republicans

do not value equity significantly more than Democrats do (t ¼ 1:56, p < 0:112).

14. George W. Bush, 2000. “October 11, 2000 Debate Transcript.” Transcript available at

https://www.debates.org/voter-education/debate-transcripts/october-11-2000-debate-

transcript/.

15. Only a random subsample of partic ipants were administe red these policy proposals,

which restricts the sample size but otherwise does not affect the analyses in this section.

16. Indeed, Mutz and Kim (2017, 842) find that holding gains for the U.S. constant, people

with low social dominance orientation—who value group equality—report greater sup-

port for trade agreements that present a win-win situation, where the U.S. trading partner

also gains jobs from the agreement.

17. See Online Appendix §2.5 for the results in tabular form, which also suggest we should

not be concerned about post-treatment bias, in that our results hold without these covari-

ates as well.

18. Zhao, Lynch Jr, and Chen (2010, 199) contend that it is not necessary to observe

“a significant zero-order effect of X on Y ...to establish mediation.” Rucker et al.

(2011, 361-62) similarly “question the requirement that a total X ! Y effect be present

before assessing mediation.” They summarize that “the lack of an effect ...does not

preclude the possibility of observing indirect effects.” We therefore rely on the theore-

tical foundations provided in literature on gender gaps to probe indirect-only mediation

despite the absence of a total effect (Rucker et al. 2011, 368).

References

Adams, J. Stacy. 1965. “Inequity in Soc ial Exchange.” Advances in Experimental Social

Psychology 2:267-99.

24 Journal of Conflict Resolution XX(X)

Powers et al. 241

Albin, Cecilia, and Daniel Druckman. 2012. “Equality Matters: Negotiating an End to Civil

Wars.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 56 (2): 155-82.

Baldwin , David Allen. 1993. Neorealism and Neolibe ralism: The Contemporary Debate.

New York: Columbia University Press.

Baum, Matthew A., and Philip B. K. Potter. 2015. War and Democratic Constraint: How the

Public Influences Foreign Policy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bayram, A. Burcu. 2015. “What Drives Modern Diogenes? Individual Values and Cosmo-

politan Allegiance.” European Journal of International Relations 21 (2): 451-79.

Bechtel, Michael M., Jens Hainmueller, and Yotam Margalit. 2017. “Policy Design and

Domestic Support for International Bailouts.” European Journal of Political Research

56 (4): 864-86.

Berinsky, Adam J. 2009. In Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion from

World War II to Iraq. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Bernauer, Thomas, Robert Gampfer, and Aya Kachi. 2014. “European Unilateralism and

Involuntary Burd en-sharing in Global Climate Politics: A Pub lic Opinion Perspe ctive

from the Other Side.” European Union Politics 15 (1): 132-51.

Bertoli, Andrew, Allan Dafoe, and Robert F. Trager. 2019. “Is There a War Party? Party

Change, the Left–Right Divide, and International Conflict.” Journal of Conflict Resolution

63 (4): 950-75.

Brooks, Deborah Jordan, and Benjamin A. Valentino. 2011. “A War of One’s Own: Under-

standing the Gender Gap in Support for War.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75 (2): 270-86.

Brooks, Stephen G., and William C. Wohlforth. 2016. America Abroad: Why the Sole

Superpower Should Not Pull Back from the World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brutger, Ryan, and Brian Rathbun. 2020. “Fair Share? Equality and Equity in American

Attitudes toward Trade.” International Organization 75 (3): 880-900.

Camerer, Colin F. 1997. “Progress in Behavioral Game Theory.” Journal of Economic

Perspectives 11 (4): 167-88.

Chilton, Adam S., Helen V. Milner, and Dustin Tingley. 2020. “Reciprocity and Public Oppo-

sition to Foreign Direct Investment.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (1): 129-53.

Chittick, William O., Keith R. Billingsley, and Rick Travis. 1995. “A Three-dimensional

Model of American Foreign Policy Beliefs.” Inte rnational Studies Quarterly 39 (3):

313-31.

Chu, Jonathan A. 2019. “A Clash of Norms? How Reciprocity and International Humanitarian

Law affect American Opinion on the Treatment of POWs.” Journal of Conflict Resolution

63 (5): 1140-64.

Clifford, Scott, Vijeth Iyengar, Roberto Cabeza, and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong. 2015. “Moral

Foundations Vignettes: A Standardized Stimulus Database of Scenarios based on Moral

Foundations Theory.” Behavior Research Methods 47 (4): 1178-98.

Cohrs, J. Christopher, Barbara Moschner, Jurgen Maes, and Sven Kielmann. 2005. “Personal

Values and Attitudes toward War.” Peace and Conflict 11 (3): 293-312.

Cram, Laura, Adam Moore, Victor Olivieri, and Felix Suessenbach. 2018. “Fair Is Fair, or Is It?

Territorial Identity Triggers Influence Ultimatum Game Behavior.” Political Psychology

39 (6): 1233-50.

Powers et al. 25

242 Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(2)