1

Southwest Business and Economics Journal 2018

Managing C2C to Increase Company Profitability

Paul D. Hutchison

University of North Texas

M. Theodore Farris II

University of North Texas

Subash Adhikari

University of North Texas

Abstract

The utilization and control of cash is essential to the survival and success of business

operations. This article presents a definition and discussion of the Cash-to-Cash (C2C) metric,

provides a brief literature review, examines how C2C can be manipulated, discusses C2C

benchmarking, provides C2C benchmarks over time and by industry, and reviews current C2C

tools. Companies that fully understand the calculation and manipulations of C2C can be more

efficient and thus, more profitable than other companies in their industry. Due to technological

advances and as Supply Chain Finance (SCF) continues to gain in popularity, C2C will continue

to play a dominant role in business operations as a tool that helps companies improve their cash

management and provides them with increased liquidity/solvency.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this article is to present and examine the cash-to-cash (C2C)

metric, seek to understand how a company can manipulate it, and provide benchmarks for

companies to use for evaluation purposes. Companies that fully understand C2C can use

it to assist them in making their business more efficient and profitable. This study will

also provide a brief literature review, current C2C benchmarks over time and by industry

and explore the ever-changing importance of C2C to business operations as Supply

Chain Finance grows in popularity as the next “low hanging fruit” in the on-going

development of supply chain management.

2. Understanding C2C

2.1. C2C Definition and Calculations

According to Kieso, Weygandt, and Warfield (2013), the operating cycle of a business

“is the period of time elapsing between the acquisition of goods and services…and the final cash

realization resulting from sales and subsequent collection.” Others use terms such as cash cycle,

cash conversion cycle, or net trade cycle to reference this same process. Essentially, these terms

are synonymous, and thus, the authors prefer to call it C2C. It has been considered to be among

the most fundamental ingredients of working capital management (Gitman 1974; Richards and

Laughlin 1980; Bodie and Merton 2000; Keown, Martin, Petty, and Scott 2003; Appuhami

Paul D. Hutchison, M. Theodore Farris II and Subash Adhikari

2

2008). Once a company has a full understanding of how the elements involved in C2C work,

they can work to reduce the cycle time. This reduction in time may lead to increased financial

and operational efficiency and ultimately, increased profitability.

There are three key financial variables from a company’s Balance Sheet: Inventory, Accounts

Receivable, and Accounts Payable involved in the C2C calculation. Next, these variables are

converted into ratios using their complimentary elements from a company’s Income Statement:

Revenues and Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). Finally, as shown below, the data is standardized by

converting the financial variables from dollars to days to produce a common measure for

analysis.

(1) Days of Inventory

(C2C)

= Inventory ($) x 365

Cost of Goods Sold ($)

(2) Days of Receivables

(C2C)

= Accounts Receivable ($) x 365

Net Sales ($)

(3) Days of Payables

(C2C)

= Accounts Payable ($) x 365

Cost of Goods Sold ($)

These three ratios represent the Inventory Conversion Period, Receivables Conversion

Period, and Payables Deferral Period, respectively (Moss and Stine 1993). Inventory

Conversion Period represents the average number of days a firm holds its inventory before

selling it. Basically, it provides information about how fast/slow a firm is selling its inventory.

Receivables Conversion Period is the average number of days it takes for a firm to collect a

receivable from a customer once the inventory has been sold on credit. It provides information

about a firm’s credit sales policy and its efficiency in collecting the credit sales. Payables

Deferral Period is the average number of days that a firm takes to pay its accounts payable to a

supplier. This measure provides information about the firm’s policy in paying back its accounts

payable. Finally, these three ratios are used to calculate C2C:

(4) Cash-to-Cash Cycle = Inventory

(C2C)

+ Receivables

(C2C)

- Payables

(C2C)

The calculated C2C may be either a positive or a negative number of days and indicates

the flow of capital with trading partners. A positive number indicates, on average, how many

days your capital is unavailable while you are awaiting payment from a customer. From a

company perspective, a high number for C2C days is unfavorable as it ties up capital assets and

increases opportunity costs or interest charges. In contrast, a negative number indicates how

many days you received cash from sales before payment is required to suppliers. Optimally, a

company would like to be close to 0 days (or negative days) (see Figure 1).

3

Southwest Business and Economics Journal 2018

Figure 1 Cash-to-Cash Positive or Negative Examples

2.2. Brief Literature Review

In addition to the current and quick ratios, C2C provides a good measure of liquidity and

solvency for companies. Further, some of the C2C elements are utilized in both of these ratios.

However, the current and quick ratios are static measures since they utilize balance sheet data

that represent a point in time. They also fail to adequately incorporate a measure of the nearness

to cash for a company. When these ratios are High, they usually suggest a greater commitment of

firm resources to less liquid forms of working capital (Gallinger 1997). They also do not account

for the time involved to convert current assets to cash, nor the time required to pay current

liabilities. Thus, C2C addresses these deficiencies since it is a dynamic metric that looks at cash

flows occurring over time and could serve as a useful alternative for liquidity analysis.

In the past, several research studies have examined the relationship between C2C and

various firm performance measures. A study by Shin and Soenen (1998) examined the

association between a company’s C2C and profitability between 1975 and 1994. Their results

suggest a negative association between C2C and profitability and risk-adjusted stock returns (i.e.,

better C2C performance results in higher profitability and stock returns). In another research

study, Wang (2002) used a sample of Japanese and Taiwanese firms from 1985 to 1996 to focus

upon the relationship between C2C and return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE).

Results from this study indicate a negative association between C2C and ROA, and C2C and

Teruel and Martinez-Solano (2007) used small-to-medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in Spain

from 1996 to 2002 in their research and determined a similar relationship (i.e., shorter C2C was

again associated with increased profitability as measured by ROA).

Paul D. Hutchison, M. Theodore Farris II and Subash Adhikari

4

Additional research studies with samples from other countries provide some evidence

consistent with the empirical results of prior literature. For example, Lazaridis and Tryfonidis

(2006) used a sample of companies from Greece; Raheman and Nasr (2007) examined

companies from Pakistan; and Charitou, Elfani, and Lois (2010) used firms on the Cyprus Stock

Exchange. All three studies found shorter C2C was associated with improved measures of

profitability. Additionally, Bhutto, Abbas, Rehman, and Shah (2011) used Pakistani industries to

confirm the relationship between C2C and profitability. Their results suggest a negative

relationship between the length of C2C and sales revenue, ROE, and firm financing policies, yet

a positive relationship for total assets, ROA, and investing policies.

The relationship of C2C and firm profitability is also supported by a theoretical

framework developed by Gomm (2010) which showed C2C, as a component of supply chain

finance, may possibly improve bottom line results for a company. Given the link between a

company's profitability and stock returns, C2C is a useful tool to examine aspects of a firm’s

cash management over time and to compare a firm’s performance within the same industry.

Longitudinal analysis of C2C information may also offer insights as to whether there is an

increased focus by an industry and how the focus changes over time. Also, strong supply chain

collaborations may lead to increased profit and improved competitive advantage (Randall and

Farris 2009a).

Finally, Farris and Hutchison (2003) provided benchmark C2C medians in 2001 for

various (non-service) industries, while Farris, Hutchison, and Hasty (2005) extended their

research by providing C2C benchmark medians for various service industries. Both studies

helped to identify key drivers for C2C changes, and suggest that firms have made concerted

efforts to manage their C2C variables.

2.3. Manipulating C2C

To minimize C2C days, a company seek to reduce days of Inventory, reduce days of

Accounts Receivable, or increase days of Accounts Payable. While all three C2C variables may

be examined individually at different times, the optimum approach for a company is to manage a

combination of all three variables and seek to reduce overall C2C days.

Historically, firms have focused on inventory reduction by applying improved computer

and equipment technology. They have also embraced concepts such as just-in-time and produce-

to-order, instead of produce-to-forecast; liquidated excess and obsolete inventory to allow more

capacity and free up capital; implemented real-time inventory tracking; synchronized

supply/demand planning; and developed trading partner agreements to strategically shift

inventory within the supply chain.

To reduce days of Accounts Receivable, a company should regularly review its credit

terms with customers. To speed up cash collections, companies may consider requiring full or

partial payments up front for purchases or using cash discounting—a percent discount for early

cash payment on invoices. A company may identify which customers who are habitually late in

their payments, review the frequency of when the firm sends delinquency notices, and

periodically assess whether to keep or terminate delinquent customers. (Easton, McAnally,

5

Southwest Business and Economics Journal 2018

Sommers, and Zhang 2015). Internally, a firm may delay sales commissions until receivables are

paid to incentivize its sales personnel to assist in credit collections. The company may also

consider factoring selected accounts receivable to third parties. The purchaser assumes the risk of

collectability and absorbs any credit losses.

Accounts Payable days may be increased by taking advantage of supplier terms. Thus, a

company may set up pre-established payments to a supplier electronically at the limit of their

credit days. This insures that timely payments are made within established credit terms, yet

reduces the time that cash is tied in the payment process. Additionally, a firm may consider

negotiating terms with suppliers to extend payment times. If a company is a significant customer

with a supplier, then they may be in a strong position in the supply chain to influence and extend

their payment terms.

2.4. C2C Benchmarking

The C2C metric is easily calculated and offers many managerial implications. To gain

insights and understanding of the efficiency of its working capital, Soenen (1993) suggested that

C2C might be of interest to any individual firm that wanted to compare itself with other firms in

the same industry. Within a company, it serves as a measure of change across time for variables

reaching internally across functional silos. It may be used to compare performance between

divisions or product lines. Externally, it may be used to benchmark performance by comparing

performance against competition within an industry or with non-competing industries with

similar performance of C2C variables (Farris and Hutchison 2003; Farris, Hutchison, and Hasty

2005; Hutchison, Farris, and Fleischman 2009; Randall and Farris 2009b).

3. C2C Database

The Compustat database (2017) was mined to retrieve historical data for annual

inventory, accounts receivable, accounts payable, COGS, and Sales for all companies from 1984

to 2016. (For a full discussion of how the C2C database was developed, please see the

Appendix.)

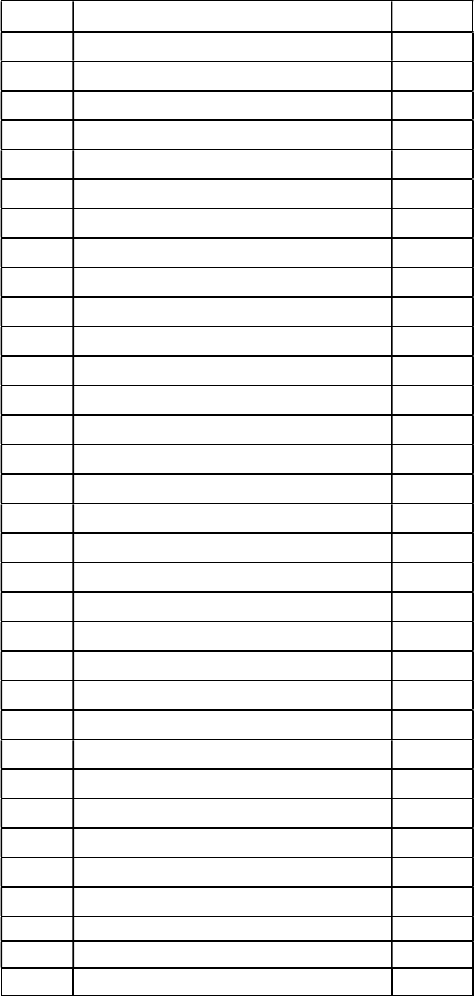

Longitudinally for all industries, C2C has improved over time, trendlines evidence that

there has been a reduction in Accounts Receivable days and minor increases in Inventory and

Accounts Payable days (see Table 1 and Figure 2). Overall, this suggests that companies are

managing all three variables of C2C over time, and that this trend will likely continue into the

future.

Paul D. Hutchison, M. Theodore Farris II and Subash Adhikari

6

Table 1: C2C Overall Median Performance

1984-2016

*

Year Inventory + A/R - A/P = C2C

1984

81.9 47.7 36.8 92.8

1985

68.3 50.5 37.2 81.7

1986

68.4 51.1 37.8 81.7

1987

70.9 52.5 39.8 83.6

1988

68.1 51.5 39.8 79.8

1989

66.6 50.7 39.5 77.8

1990

65.1 50.0 39.0 76.2

1991

63.2 49.8 38.3 74.8

1992

64.1 50.3 38.8 75.5

1993

61.9 50.0 39.7 72.3

1994

61.0 52.0 41.3 71.8

1995

61.1 52.0 41.7 71.4

1996

60.9 52.0 41.2 71.6

1997

60.6 52.9 41.3 72.1

1998

61.1 53.1 42.1 72.1

1999

60.5 53.7 44.0 70.2

2000

60.0 52.8 43.9 68.9

2001

55.0 47.1 39.5 62.6

2002

55.9 47.4 41.2 62.1

2003

54.7 47.9 41.7 60.9

2004

55.1 48.3 42.8 60.7

2005

53.7 49.0 43.7 59.0

2006

55.3 48.3 43.2 60.4

2007

54.9 48.5 44.1 59.3

2008

52.9 42.9 39.0 56.8

2009

54.2 46.5 41.8 58.8

2010

54.4 46.2 44.2 56.4

2011

54.6 44.8 42.3 57.1

2012

54.7 44.7 42.4 57.0

2013

53.0 44.9 42.9 55.0

2014

52.9 44.6 42.8 54.7

2015

52.0 43.7 41.7 54.0

2016

55.0 46.7 44.4 57.3

7

Southwest Business and Economics Journal 2018

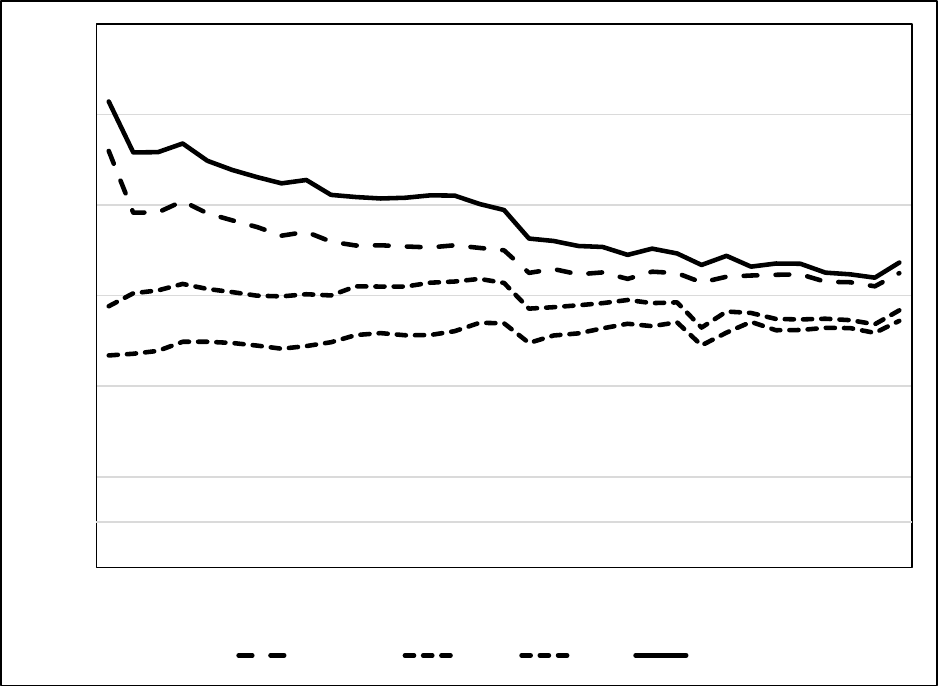

Figure 2: C2C Overall Machine Performance

1984-2016

*

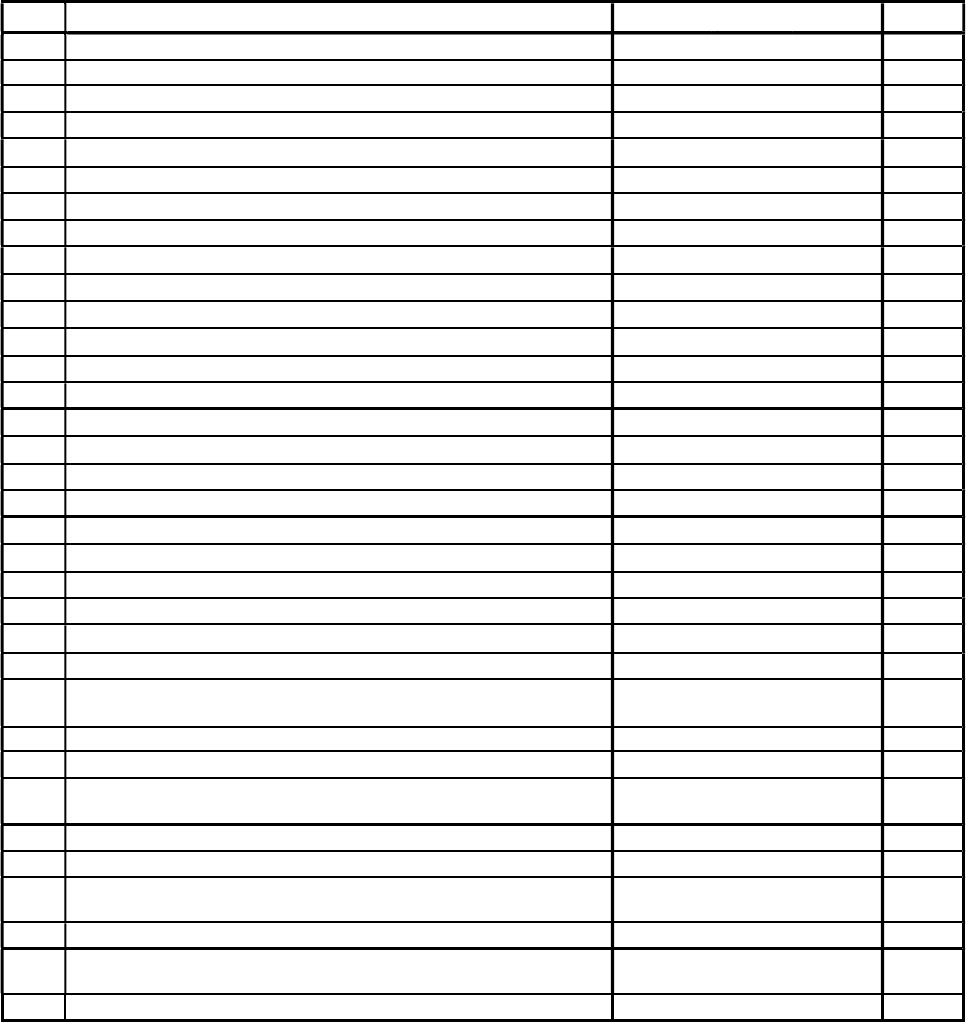

Using C2C and classifying by industries helps identify where performance may be

benchmarked against non-competing industries. Since medians serve to generalize industry

characteristics, all industries were rank ordered based on median performance for the three

variables (Inventory, Accounts Receivable, and Accounts Payable), and then split into two

groups: HIGH and LOW. A 2 x 2 x 2 matrix was created to classify industries by the

characteristics of the three variables. The matrix shown in Table 2 may be used by a company to

identify comparable industries for benchmarking their C2C.

-10

10

30

50

70

90

110

1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016

C2C Days

Year

Inventory A/R A/P C2C

Paul D. Hutchison, M. Theodore Farris II and Subash Adhikari

8

Table 2: C2C Benchmarking Map by SIC Industry 2016

*

HIGH

INVENTORY

LOW

INVENTORY

HIGH

HIGH A/P

2600

Paper and Allied Products

2800

Chemicals and Allied Products

3000

Rubber and Miscellaneous Plastic

Products

3400

Fabricated Metal Products, Except

Machinery and Transportation

Equipment

3500

Industrial and Commercial Machinery and

Computer Equipment

3600

Electronic and Other Electrical Equipment

and Components, Except Computer

Equipment

3800

Measuring, Analyzing, and Controlling

Instruments; Photographic, Medical

5000

Wholesale Trade-Durable Goods

HIGH A/P

1300

Oil and Gas Extraction

4800

Communications

4900

Electric, Gas, and Sanitary Services

7300

Business Services

A/R LOW A/P

3700

Transportation Equipment

LOW A/P

1600

Heavy Construction, Except Building

Construction-Contractors

2700

Printing, Publishing, and Allied Industries

8000

Health Services

8700

Engineering, Accounting, Research,

Management, and Related Services

LOW

HIGH A/P

1000

Metal Mining

2300

Apparel and Other Finished Products

Made from Fabrics and Similar

Materials

2500

Furniture and Fixtures

HIGH A/P

4920

Gas Production and Distribution

5900

Miscellaneous Retail

A/R LOW A/P

1500

Building Construction-General

Contractors and Operative Builders

2000

Food and Kindred Products

2400

Lumber and Wood Products, Except

Furniture

3300

Primary Metal Industries

5500

Automotive Dealers and Gasoline Service

Stations

LOW A/P

2900

Petroleum Refining and Related Industries

3200

Stone, Clay, Glass, and Concrete Products

4400

Water Transportation

4500

Transportation by Air

5100

Wholesale Trade-Nondurable Goods

5800

Eating and Drinking Places

7900

Amusement and Recreation Services

For 2016, one of the top C2C industry performers was SIC 5800 Eating and Drinking

Places which passes the common sense test when one considers the dining experience. One

prefers eating fresh food (which results in low days of inventory), pays using cash or quick to

collect credit or debit cards (low days of receivables), and the restaurateur pays suppliers on a

traditional 30/60/90 days’ cycle (extending days of payables).

The poorest performer was SIC 1500 Building Construction-General Contractors and

Operative Builders. This too passes the common sense test, as construction time accounts for a

9

Southwest Business and Economics Journal 2018

high number of days of inventory, payment for the finished product occurs rather quickly as

financial institutions make a quick payment to convert the accounts payable into a long-term

loan with the buyer, and payment to suppliers and employees tends to be rather short.

Table 3: Best SIC Industry C2C Performance 2016

*

SIC Category Inventory + A/R - A/P = C2C

4500 Transportation by Air 9.3 14.5 34.7 -10.9

4800 Communications 13.2 47.8 66.7 -5.7

7900 Amusement and Recreation Services 5.3 14.6 17.3 2.6

5800 Eating and Drinking Places 3.9 6.6 13.2 2.7

5900 Miscellaneous Retail 36.9 17.9 45.6 9.2

4400 Water Transportation 19.3 16.2 21.2 14.3

4920 Gas Production and Distribution 25.2 38.6 46.7 17.1

4900 Electric, Gas, and Sanitary Services 30.7 41.8 48.5 24.0

1300 Oil and Gas Extraction 19.7 60.8 53.4 27.1

5100 Wholesale Trade-Nondurable Goods 26.5 29.3 26.2 29.6

7300 Business Services 12.4 61.9 41.8 32.5

8000 Health Services 10.7 46.2 23.9 33.0

2900 Petroleum Refining and Related Industries 40.4 29.4 36.0 33.8

2700 Printing, Publishing, and Allied Industries 20.0 50.8 33.9 36.9

1000 Metal Mining 91.1 9.6 56.6 44.1

3200 Stone, Clay, Glass, and Concrete Products 45.4 39.0 39.8 44.6

2000 Food and Kindred Products 55.3 30.8 39.1 47.0

2400 Lumber and Wood Products, Except Furniture 49.0 25.5 21.3 53.2

2600 Paper and Allied Products 59.7 43.7 47.8 55.6

1600 Heavy Construction, Except Building Construction-Contractors 25.9 70.8 36.6 60.1

2500 Furniture and Fixtures 68.6 38.0 46.4 60.2

3700 Transportation Equipment 57.3 51.8 39.1 70.0

3000 Rubber and Miscellaneous Plastic Products 76.0 40.5 43.7 72.8

3300 Primary Metal Industries 72.9 38.5 38.6 72.8

8700 Engineering, Accounting, Research, Management, and Related

Services

34.9 73.9 34.7 74.1

5500 Automotive Dealers and Gasoline Service Stations 71.4 12.9 10.1 74.2

5000 Wholesale Trade-Durable Goods 76.0 46.6 40.8 81.8

3600 Electronic and Other Electrical Equipment and Components,

Except Computer Equipment

85.6 55.5 59.1 82.0

2800 Chemicals and Allied Products 87.1 53.5 52.4 88.2

3500 Industrial and Commercial Machinery and Computer Equipment 88.1 61.2 48.6 100.7

2300 Apparel and Other Finished Products Made from Fabrics and

Similar Materials

119.1 39.1 49.8 108.4

3400

Fabricated Metal Products, Except Machinery and

Transportation

104.7 51.2 46.0 109.9

3800

Measuring, Analyzing, and Controlling Instruments; Photographic,

Medical

132.6 58.3 49.1 141.8

1500 Building Construction-General Contractors and Operative Builders 399.6 5.0 23.3 381.3

Paul D. Hutchison, M. Theodore Farris II and Subash Adhikari

10

4. Current C2C Tools

With constant improvements in computer technology, companies today are able to obtain

data easily to better manage their cash. The following are suggested opportunities that firms

could utilize to enhance and improve their C2C days and profitability:

Dynamic C2C Tracking and Management—Using computer generated data and a dashboard

approach, companies could constantly monitor in real-time their C2C variables (Inventory,

Accounts Receivable, and Accounts Payable) as data is updated and transactions occur. This

dashboard provides company management the ability to monitor C2C for problems so that they

can quickly determine solutions to meet budgeted C2C goals.

Supply Chain Mapping—Understanding a company’s strength and weakness in the supply

chain relative to its trading partners and customers allows a company to develop a graphic map

for visualization of all trading partners. This lets a company visualize the strong and weak

performers in relation to a company and their associations with other companies. It helps a

company visualize its strengths when negotiating receivable and payable terms (Farris 2010).

Dynamic Discounting—Most companies are aware of conventional/traditional cash discount

terms such as 2/10, net 30 days which are static and all (2% off if payment is received by the 10

th

day) or none (net payment due at day 30). An improvement to these terms is dynamic

discounting that provides cash discount for payment to customers on a sliding scale basis from

the date and time of a sale. The cash discount is reduced on a periodic time basis until the end of

the credit term. This approach to discounting gives the customer a graduated incentive to make

earlier payment and improve their payables process for the benefit of both trading partners.

Reverse Factoring—As a financing solution for suppliers, reverse factoring occurs when a

company, the ordering party, assists their suppliers in financing their receivables at a lower

interest rate than what may be obtained in the market (Aberdeen 2011). The goal for a company

is to help suppliers manage their cash flows, reduce costs, and decrease default risks in the

supply chain by improving their liquidity (Tsai 2008; Tsai 2012).

Supply Chain Balancing—Entails a company working in concert with its trading partners to

manage inventories, accounts receivable, and accounts payable across the supply chain. The goal

with this approach is to lower inventory carrying costs and lower costs of capital. The savings

earned could be shared equally among the trading partners and would benefit them with

profitability increases (Hutchison, Farris, and Fleischman 2009; Randall and Farris 2009a).

5. Conclusions

This article sought to present and discuss the C2C metric and provide benchmarks to

allow companies to draw comparisons. This was accomplished by reviewing the basics of C2C

and its manipulations, presenting a brief literature review, plus providing companies with current

C2C benchmarking data that shows C2C performance from 1984 to 2016. Also, industry

11

Southwest Business and Economics Journal 2018

performance by the three C2C variables (Inventory, Accounts Receivable, and Accounts

Payable) and overall best performance by industry were presented for the same time period.

Current C2C tools were presented to allow companies to improve their C2C performance and

profitability.

In the future, as technology continues to advance rapidly, companies will use the C2C

metric as a Supply Chain Finance tool to gain competitive advantage, become more efficient in

their operations, and increase their profitability. Overall, C2C will be an important metric for

companies in a dynamic and changing environment, and understanding its calculations and

manipulations will allow companies to improve their overall liquidity.

References

Aberdeen. (2011). Supply Chain Finance. (January).

Appuhami, B. A. R. (2008). “The Impact of Firms' Capital Expenditure on Working Capital

Management: An Empirical Study Across Industries in Thailand.” International

Management Review 4, no. 1: 8-21.

Bhutto, N. A., G. Abbas, M. Rehman, S. M. M. Shah. (2011). “Relationship of Cash Conversion

Cycle with Firm Size, Working Capital Approaches and Firm’s Profitability: A Case of

Pakistani Industries.” Pakistan Journal of Engineering Technology, & Science 1, no. 2:

45-64.

Bodie, Z., and R. Merton. (2000). Finance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Charitou, M. S., M. Elfani, and P. Lois. (2010). “The Effect of Working Capital Management on

Firm’s Profitability: Empirical Evidence from an Emerging Market.” Journal of Business

& Economics Research 8, no. 12: 63-68.

Easton, P. D., M. L. McAnally, G. Sommers, and X.-J. Zhang. (2015). Financial Statement

Analysis & Valuation (4

th

ed.). Westmont, IL: Cambridge Business Publishers, LLC.

Farris II, M. T. (2010). Solutions to Strategic Supply Chain Mapping Issues. International

Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 40, no. 3: 164-180.

Farris II, M. T., and P. D. Hutchison. (2003). “Measuring Cash-to-Cash Performance.” The

International Journal of Logistics Management 14, no. 2: 83-92.

Farris II, M. T., P. D. Hutchison, and R. W. Hasty. (2005). “Using Cash-to-Cash to Benchmark

Service Industry Performance.” Journal of Applied Business Research 21, no. 2: 113-124.

Gallinger, G. (1997). “Drop the Current Ratio: Pick Up the CCC.” Business Credit 99, no. 5: 24-

25.

Paul D. Hutchison, M. Theodore Farris II and Subash Adhikari

12

García-Teruel, P. J., and P. Martinez-Solano. (2007). “Effects of Working Capital Management

on SME Profitability.” International Journal of Managerial Finance 3, no. 2: 164-177.

Gitman, L. J. (1974). “Corporate Liquidity Requirements: A Simplified Approach.” The

Financial Review 9, no. 1: 79-88.

Gomm, M. L. (2010). “Supply Chain Finance: Applying Finance Theory to Supply Chain

Management to Enhance Finance in Supply Chains.” International Journal of Logistics:

Research and Applications 13, no. 2: 133-142.

Hutchison, P. D., M. T. Farris II, and G. Fleischman. (2009). “Supply Chain Cash-to-Cash:

Strategy for the 21

st

Century.” Strategic Finance 91, no. 1: 41-48.

Keown, A. J., J. D. Martin, J. W. Petty, and D. Scott. (2003). Foundations of Finance (3

rd

ed.).

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Kieso, D. E., J. J. Weygandt, and T. D. Warfield. (2013). Intermediate Accounting (15

th

ed.).

Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Lazaridis, I., and D. Tryfonidis. (2006). “Relationship Between Working Capital Management

and Profitability of Listed Companies in the Athens Stock Exchange.” Journal of

Financial Management and Analysis 19, no. 1: 26-35.

Leys, C., O. Klein, P. Bernard, and L. Licata. (2013). “Detecting Outliers: Do Not Use Standard

Deviation Around the Mean, Use Absolute Deviation Around the Median.” Journal of

Experimental Social Psychology 49, no. 4: 764-766.

Miller, J. (1991). “Reaction Time Analysis with Outlier Exclusion: Bias Varies With Sample

Size.” The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 43, no. 4: 907-912.

Moss, J. D., and B. Stine. (1993). “Cash Conversion Cycle and Firm Size: A Study of Retail

Firms.” Managerial Finance 19, no. 8: 25-34.

Raheman, A., and M. Nasr. (2007). “Working Capital Management and Profitability–Case of

Pakistani Firms.” International Review of Business Research Papers 3, no. 1: 279-300.

Randall, W. S., and M. T. Farris II. (2009a). “Supply Chain Financing: Using Cash-to-Cash

Variables to Strengthen the Supply Chain.” International Journal of Physical

Distribution & Logistics Management 39, no. 8: 669-689.

Randall, W. S., and M. T. Farris II. (2009b). “Utilizing Cash-to-Cash to Benchmark Company

Performance.” Benchmarking 16, no. 4: 449-461.

Richards, V. D., and E. J. Laughlin. (1980). “A Cash Conversion Cycle Approach to Liquidity

Analysis.” Financial Management 9, no. 1: 32-38.

13

Southwest Business and Economics Journal 2018

Shin, H., and L. Soenen. (1998). “Efficiency of Working Capital Management and Corporate

Profitability.” Financial Practice and Education 8, no. 2: 37-45.

Soenen, L. A. (1993). “Cash Conversion Cycle and Corporate Profitability.” Journal of Cash

Management 13, no. 4: 53-57.

Tsai, C.-Y. (2008). “On Supply Chain Cash Flow Risks.” Decision Support Systems 44, no. 4:

1031-1042.

Tsai, C.-Y. (2012). “The Impact of Credit Terms on Supply Chain Cash Flows—A Simulation

Approach.” Proceedings for the Northeast Region Decision Sciences Institute (NEDSI):

6-17.

Wang, Y. (2002). “Liquidity Management, Operating Performance, and Corporate Value:

Evidence from Japan and Taiwan.” Journal of Multinational Financial Management 12,

no. 2: 159-169.

Paul D. Hutchison, M. Theodore Farris II and Subash Adhikari

14

Appendix

C2C Data Development

C2C data was extracted from the Compustat database (i.e., Capital IQ, North America,

Fundamentals Annual) on April 13, 2017 for all firms in the database from January 1, 1984 to

December 31, 2016. The key variables obtained were Company Name, Year, Standard Industry

Code (SIC), Net Income (Net Loss), Sales (Revenues), Cost of Goods Sold, Inventory, Accounts

Receivable, and Accounts Payable. Initially, the dataset had 385,638 company years (or lines)

for the 33 years to be examined in this study. While the completeness of Compustat data has

improved over the years since 1984, the authors sought to groom the data. To allow C2C

calculations and comparability, lines with values reported with blanks, negative values, or zero

values for Sales (Revenues), Cost of Goods Sold, Inventory, Accounts Receivable, and Accounts

Payable were deleted. This reduced the dataset to 172,485 lines (-213,153 lines or 55%). Next,

the data was sorted by 4-digit SIC, and the authors standardized it by calculating Inventory Days,

Accounts Receivable Days, Accounts Payable Days, and C2C days.

To remove the undue influence of outliers, the authors elected to use 3 times the Median

Absolute Deviation (MAD) by 4-digit SIC for Inventory Days, Accounts Receivable Days, and

Accounts Payable Days (Leys, Klein, Bernard, and Licata 2013). Miller (1991) suggested that

MAD times 3 should be considered “very conservative” for setting negative and positive data

limits. This resulted in the removal of 36,657 lines and a final dataset of 135,828 company lines

for this study. This is an average of 4,116 companies per year.

Task

Company Years

(or lines) of data

Initial data extraction 385,638

Removal of values with blanks,

negative values, and zero values (213,153)

Subtotal 172,485

Removal of 3 times MAD ( 36,657)

TOTAL 135,828