Introduction

e upsurge in inflation that began in 2021—the

sharpest in more than three decades—has affected

fiscal accounts, worsened poverty, and altered the

distribution of households’ well-being, calling on

policymakers to respond. is chapter analyzes these

developments and explores how fiscal policy can do its

part to curb inflation while supporting the vulnerable.

1

Most people strongly dislike high and variable

inflation,

2

which causes many distortions in the

economy (Agarwal and Kimball 2022), including greater

uncertainty. Relative prices of goods and services may

become blurred—no longer reflecting relative demand

and supply conditions and making everyday decisions

about consumption, investment, and production

decisions harder for households, financiers, and firms.

Inflation is more likely to become persistent if, akin to

a tug-of-war, each group in the economy—employers

and workers, producers and consumers, and retailers

and their suppliers—tries to hold on to its share of

prosperity at the expense of others. If such social

tensions lead to inconsistent macroeconomic policies

(for example, monetary policy that is too loose), high

inflation will persist longer, ultimately prolonging a

costly phenomenon for everyone.

Inflation often leads to a rise in poverty from

loss of purchasing power (Cardoso 1992), and,

as with any adversity, poor families tend to suffer

is chapter was prepared by staff from the Fiscal Affairs

Department. e authors of this chapter are Marcos Poplawski-

Ribeiro (team lead), Carlos Eduardo Gonçalves (team co-lead),

Chadi Abdallah, Vybhavi Balasundharam, Yongquan Cao, Daniel

Garcia-Macia, Andres Ghini, Ting Lan, Anh Dinh Minh Nguyen,

Julieth Pico Mejía, and Alberto Tumino, with research support

from Kardelen Cicek, Arika Kayastha, Zhonghao Wei, and Andrew

Womer, and under the guidance of Paolo Mauro and Paulo Medas.

1

Although the spike in prices during 2021–22 was initially

concentrated in food and energy, this chapter discusses inflation

more generally as a sustained rise in the prices of many goods

and services, which may originate from different sources. e

analysis measures inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI),

complementing it with the GDP deflator in specific exercises. For

recent developments on the relationship between inflation and

public finances, see also Chapter 1.

2

See survey results in Shiller (1997), Scheve (2001), and Prati (2022).

disproportionately more because they consume more

as share of their income and they lack buffers in the

form of accumulated savings. But the distributive

effects of inflation stemming from its uneven impacts

on the budgets of different households are far more

complex. In turn, these depend on various factors,

including the source of price increases (for example,

food or energy prices) and their form (demand,

or wage push); households’ consumption baskets,

sources of income, and the size and composition

of their balance sheets (for example, their position

as net borrowers or lenders); and policy design and

responses (such as indexation of wages, pensions,

and social safety nets). Government policies need to

be informed by an understanding of how inflation

affects various groups in society. Greater availability

of household data makes it possible to analyze how

big those effects are, which channels affect them, and

how they vary across households.

3

e impact of inflation on the fiscal accounts also

depends on redistribution—in this case, between the

public sector and the private sector. An unexpected

bout of inflation erodes the real (inflation-adjusted)

value of public debt, at least in the near term, with

bondholders bearing the loss. Likewise, deficit-to-GDP

ratios decline because the nominal (current monetary)

values of the economy’s output and of tax bases

will generally rise, generating more revenues, while

spending—often set in nominal terms in the budget—

initially fails to keep up. Without indexation, real

incomes decline for civil servants, pensioners, and

recipients of welfare transfers. e quality of public

services may also suffer as nominal spending ceilings

clash with higher costs of goods and services. e early

decline in deficits as a share of GDP may not last over

the medium term; yet, as inflation becomes expected,

spending catches up, and the cost of borrowing

rises as investors require an inflation risk premium

3

Empirical analyses of historical episodes have been constrained by

limited availability of comparable data. A study based on surveys of

overall incomes of households in Israel with at least one employee,

for the period 1950−91 (including the hyperinflation of the

mid-1980s), reports evidence of a statistically significant correlation

between inflation and inequality in incomes (Dahan 1996).

INFLATION AND DISINFLATION: WHAT ROLE FOR FISCAL POLICY?

CHAPTER

2

International Monetary Fund | April 2023 1

FISCAL MONITOR: ON THE PATH TO POLICY NORMALIZATION

2 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

and central bank policy rates are hiked. Initial fiscal

gains may even be reversed in some cases, notably if

growth falters.

High and volatile inflation thus makes fiscal

management more challenging, potentially

undermining the credibility of economic institutions

and of the fiscal framework. Fiscal planning and

budget preparation become more complex not only

because of uncertainty regarding prices, wages,

and interest rates but also because the overall fiscal

stance affects inflation through aggregate demand

and through inflation expectations (Coibion,

Gorodnichenko, and Weber 2021).

Governments can influence how the costs of

inflation are allocated, via indexation or discretionary

policy decisions. ey could choose, for example, to

let inflation quietly increase taxation while eroding

public pensions, wages, and transfers or instead seek

to keep the real values of these variables unchanged.

ey could also make the tax or transfer more or less

progressive by adjusting some items but not others.

Further complicating policymakers’ task, widespread

indexation of public wages and other expenditure

items would entrench inflation expectations and make

inflation more persistent. Such anticipation of inflation

makes price stability harder to achieve. Similarly, if

untargeted support outlasts spikes in energy prices or

other prices that originally motivated it, fiscal costs

and contributions to aggregate demand would be

unnecessarily prolonged (October 2022 Fiscal Monitor,

Chapter 1). High inflation can lead to policy mistakes

that may ultimately hamper investment and economic

growth, whereas price stability helps all individuals in

the economy.

Against this backdrop, it is timely to review what

we know about these variegated interactions between

inflation and fiscal variables and draw lessons for

the conduct of fiscal policy. e chapter analyzes the

following questions:

• How does inflation affect fiscal accounts? And how do

the effects depend on institutional features of the tax

and benefit system, such as indexation? The section

“Impact of Inflation on Public Finances” reviews

the mechanisms through which inflation affects

public finance; surveys indexation practices across

the world; and estimates the impact of inflation on

public debts, deficits, expenditures, and revenues in

the near and medium term.

• How large are the distributive effects of inflation across

households in countries at different levels of economic

and financial development, and what is the role of

fiscal policy? The section “Distributive Effects of

Inflation and Fiscal Policy Support” analyzes the

impact of inflation on poverty and the distribution

of consumption, income, and net wealth, using

household surveys for six countries at different levels

of economic and financial development.

• What is the role of fiscal policy in the efforts to

promote price stability? The section “Disinflating

and Distributing” estimates the impact of fiscal

policy on inflation through aggregate demand.

Using model simulations that allow for distributive

effects, it explores how fiscal policy can support

monetary policy to curb inflation while protecting

vulnerable households.

e conclusion summarizes the chapter’s policy

implications.

Impact of Inflation on Public Finances

Inflation can affect fiscal aggregates through multiple

channels, with varying effects over time (Dynan 2022;

US CBO 2022a).

Direct Channels of Impact

e main direct channels through which inflation

affects public finances, abstracting from subsequent

fiscal and monetary policy reactions, are listed below

and sketched out in the Executive Summary.

• Inflated nominal values for GDP and the tax base.

Higher nominal output lowers debt and deficits as

a share of GDP. The nominal tax base also grows

with inflation. For example, more revenues from

value-added taxes are collected as the prices of

underlying goods and services go up. For some

taxes, such as income taxes, revenues may increase

even more than one-for-one with inflation,

including because some taxpayers may jump over

nominal thresholds to higher tax brackets (bracket

creep).

4

These effects also depend on the degree of

4

Beer, Griffiths, and Klemm (2023) analyze further channels

through which inflation affects the real value of collected tax

revenues, including the erosion of such revenues if inflation is high

and they are collected with a lag (Tanzi 1977).

CHAPTER 2 INFLATION AND DISINFLATION: WHAT ROLE FOR FISCAL POLICY?

3International Monetary Fund | April 2023

indexation (in this case, of thresholds), discussed

later in the chapter.

• Inertia in nominal spending. The net response

of the fiscal balances to inflation depends on

whether expenditure keeps pace with revenues.

During the budget year, this is seldom the case

because spending caps are usually set in nominal

terms, although indexation of some important

items such as public wages and transfers may

lead in some cases to automatic adjustments to

inflation in the same year. Ad hoc adjustments

or new measures such as introduction or

enhancement of subsidies (for example, in

response to higher food or energy prices) can also

speed up the rise in nominal spending.

• Sovereign debt size and structure, and investors’

response. The larger the debt, the greater the

potential erosion from inflation. This effect is

attenuated, however, if a portion of the debt is

inflation-linked (as inflation automatically leads

to higher borrowing costs), is denominated in

foreign currency (as inflation leads to depreciation,

potentially resulting in higher repayments when

expressed in domestic currency), has a floating

rate (as inflation prompts higher policy, and

hence higher short-term benchmark rates), or

has a greater share of short-term bonds that are

maturing and need to be rolled over (as investors

will ask for higher rates on newly issued bonds).

When governments issue new debt, investors may

require higher returns to compensate not only for

expected inflation but also for higher inflation

volatility (an inflation risk premium)—and, for

countries where economic prospects are uncertain

and the debt ratio remains high or keeps rising, a

default premium.

International Practices with Inflation Indexation

Countries’ practices vary regarding how much tax

or budget items are indexed to inflation or adjusted

to inflation by policy measures. is has consequences

for how their public finances evolve in the face of

inflation surprises. Indexation of politically salient

expenditure items such as pensions or wages is often

a prominent topic in public discourse. e effects

on the revenue side, while less discussed, are no less

relevant. If income tax thresholds are not adjusted to

inflation, for example, taxpayers may be pushed into

higher tax brackets (bracket creep), or the value of

their tax allowances and deductions may be eroded.

e degree of indexation involves trade-offs. On

one hand, indexing public wages, pensions, or welfare

transfers reduces uncertainty and preserves purchasing

power for civil servants, retirees, and low-income

households. It may also prevent distortionary gaps

between public and private wages or a possible brain

drain from the public sector. On the other hand,

indexation sustains real expenditures, contributing to

aggregate demand and potentially making inflation

more persistent. If public wages are a benchmark for

private wages (as in many countries), indexation of

public wages could prolong wage and inflationary

pressures (Box 2.1). Widespread indexation can limit

the scope for discretionary cuts.

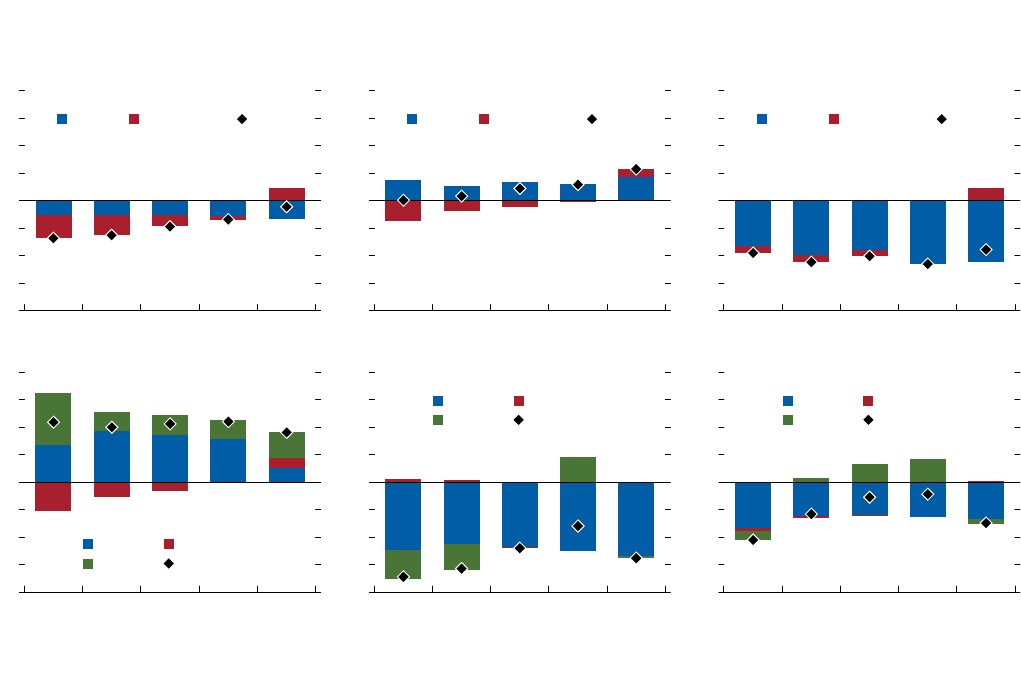

Countries have taken different approaches to

indexation policies (Figure 2.1). A minority of

countries index or regularly adjust their income tax

rate brackets to minimize bracket creep.

Indexation is more common for some important

expenditure items, especially pensions. Nearly all

advanced economies, about 50 percent of emerging

market economies, and 30 percent of low-income

developing countries have some form of indexation.

Pension indexation has become more prevalent

recently, but many countries have made it less generous

to reduce the burden on the budget and safeguard

the sustainability of pension systems (OECD 2022a).

Countries have moved from wage indexation toward

price indexation as nominal wage increases have

tended to exceed price inflation in the past, reflecting

productivity gains.

5

Many countries further index

their social assistance programs, with around half of

advanced economies linking several of their benefits to

inflation (OECD 2022c). By contrast, most countries

do not index public wages to inflation—a practice that

has become less prevalent in recent decades, perhaps

because inflation had been low. But the pressure

to index wages may return if high inflation persists

(Suthaharan and Bleakley 2022).

6

5

In 2022, such a strategy may have been costlier than predicted

given that inflation rose faster than nominal wages (OECD 2022d).

6

For public wages, their increases in most countries tend to be

related to the political cycle rather than to indexation (Gaspar,

Gupta, and Mulas-Granados 2017).

FISCAL MONITOR: ON THE PATH TO POLICY NORMALIZATION

4 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

Effects of Inflation on Public Finances over

the Medium Term

Inflation surprises often improve debt and budget

balances in the near term, but are these gains

maintained over the medium term? To answer this

question, the chapter employs both quarterly and

annual data.

7

e effects of inflation on public finance

could ebb over time for three main reasons. First,

7

Recent attempts to answer this question have used different

methods, including event studies (Blanco, Ottonello, and Ranosova

2022), model-based simulations (Bénassy-Quéré 2022), and surprises

in World Economic Outlook forecasts (October 2022 Fiscal Monitor,

Chapter 1). e US Congressional Budget Office’s 2002 workbook

allows users to simulate alternative economic scenarios by specifying

different values for inflation (and three other economic variables) for

the United States, comparing them to its baseline projections (US

CBO 2022b). e estimates in this section use the local projection

method (Jordà 2005). e annual historical data include many more

(emerging market) economies, allowing the research of samples where

inflation is higher, more volatile, and less surprising (more persistent).

Quarterly data provide more accurate estimates of the immediate

effects of CPI inflation on fiscal variables. See Online Annex 2.2.

public spending could catch up with revenues through

indexation. Second, public policies and decisions,

including for wages or pensions, could lead to higher

spending over time, reducing any initial gains for public

finance indicators. ird, most central banks have the

statutory objective of maintaining price stability, using

adjustments in their policy rates to do so, which may

lead to a tightening of financial conditions for agents in

the economy, including the government. Even so, the

adjustment of interest expense may be gradual if the

structure of public debt is mostly in its own currency

and in long maturities and if the country’s monetary

authority has a reputation for maintaining price stability.

In such cases, exchange rate risks may be muted and

market expectations well anchored. A debt structure

with longer maturities will facilitate less pass-through of

interest rates to increases in public interest payments in

the medium term.

Analysis using historical annual data (1962−2019)

for 85 economies shows that, on average, spikes in

No regular adjustments

Regular de facto adjustments

Automatic price adjustments

Price

Wage

Mixed No

No

Yes, to other variables

Yes, to inflation

No

Yes, to other variables

Yes, to inflation

Figure 2.1. Indexation Policies Vary across the World and across Budget Items

(Percentage of countries in each income group)

1. Personal Income Tax

Brackets’ Indexation

1

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

AEs EMs LIDCs

2. Pension Indexation

2

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

AEs EMs LIDCs

3. Social Assistance Program

Indexation

3

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

AEs EMs LIDCs

4. Public Wages Indexation

4

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

AEs EMs LIDCs

Sources: IMF staff analysis based on an IMF survey and using ad

ditional data from Beer, Griffiths, and Klemm (2023); IMF Pay Sy

stems database (2016); International Social

Security Association database; OECD (2022c); and US Social Secu

rity Administration databases.

Note: Panels include data for 2016–23. Observations vary from 1

16 to 176 countries in each panel (see Online Annex 2.1 for details). Price indexation includes different

measures of inflation, for example, “core,” or measures that inc

lude only urban workers or exclude fuel, tobacco, alcohol, and others. Even with automatic indexation,

discretionary approval stages may be part of the framework that

result in ad hoc adjustments. AEs = advanced economies; EMs = emerging market economies;

LIDCs = low-income

developing countries.

1

“Regular de facto adjustments” means that personal income tax thresholds are regularly revised but not automatically.

2

“Mixed” indexation refers to an adjustment that includes a mix of price, wages, and other variables.

3

Social assistance programs include major fixed cash transfer programs. “Yes” means that majority of benefits are indexed in the country.

4

“No” means that inflation does not play an automatic or mandatory role in the setting of public wages. Indexation includes both partial and full indexation.

CHAPTER 2 INFLATION AND DISINFLATION: WHAT ROLE FOR FISCAL POLICY?

5International Monetary Fund | April 2023

the growth of the GDP deflator tend to reduce the

debt-to-GDP ratio persistently (Figure 2.2).

8

e drop

in the debt-to-GDP ratio is larger in economies with

higher initial debt, as expected, with an initial spike of

1 percentage point in the growth of the GDP deflator

9

associated with a persistent cumulative decline in the

debt ratio of 0.6 percentage point of GDP (see also

Chapter 1 for recent developments on the relationship

between inflation and debt). e reduction in the debt

ratio is caused by a hike in the GDP denominator and

an initial rise in fiscal balances. e debt and fiscal

balance reactions to a spike in the growth of the GDP

deflator are similar between advanced and emerging

market economies. Yet the drop in debt is significantly

smaller in countries with flexible exchange rates, as

in those countries, inflation tends to be associated

with exchange rate depreciation, increasing the value

of foreign-currency-denominated debt relative to

domestic GDP (see Online Annex 2.2).

8

e result is qualitatively robust to the use of CPI inflation.

To capture inflation from all sources, the estimates employ ordinary

least squares regressions (panels with fixed effects). e analysis

excludes countries with 2019 population of less than 1 million.

9

roughout the chapter, a “spike” in inflation refers to a sudden

rise in inflation followed by a gradual decline. Specifically, when

using annual data, a spike is a 1 percentage point increase in the

GDP deflator growth rate, followed by gradual decline in subsequent

years (see Online Annex Figure 2.2.1). When using quarterly data,

the spike in CPI inflation stems from a 1 percentage point increase

in commodity import inflation (weighted by GDP), with CPI

inflation petering out after three quarters (see Figure 2.4, panel 1).

Whereas unexpected spikes in inflation reduce the

debt ratio, increases in inflation expectations do not. e

latter are associated with a faster rise in both primary

spending and interest expense, and a smaller increase in

the nominal GDP denominator. e difference in the

effects of surprise versus expected inflation is larger for

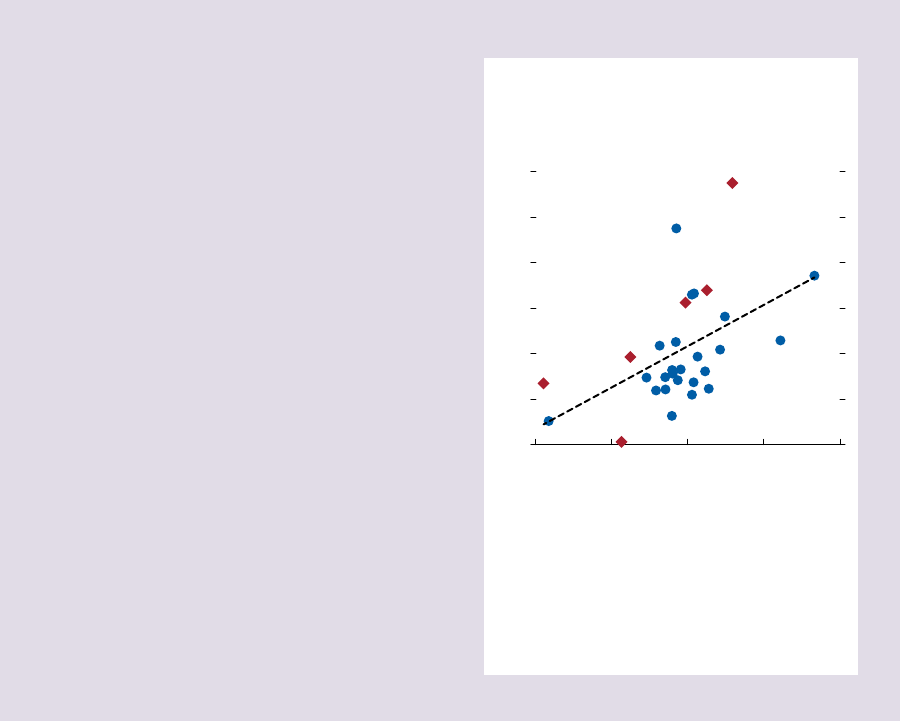

countries with high initial debt levels (Figure 2.3). Both

results underscore that attempting to inflate public debt

away is neither a desirable nor a sustainable strategy.

If inflation surprises frequently, agents will adjust

their inflation expectations accordingly and demand

protection against it, leading to higher spreads owing to

the inflation risk.

Estimates using quarterly data from the first quarter

of 1999 to the fourth quarter of 2019 for 28 advanced

economies confirm that CPI inflation spikes tended

to improve the overall and primary fiscal balances in

the short term (Figure 2.4).

10

High-frequency data

capture the immediate effects of inflation on public

10

Regressions with quarterly data are estimated using

instrumental variables. CPI inflation spikes are instrumented by

the change in the price growth of the commodity import basket,

also interacted with an exchange rate peg dummy (lagged).

Commodity price spikes tend to be more surprising and tend to

pass through to prices of various goods and services (see Choi

and others 2018). e correlation is clear for countries with more

flexible exchange rate regimes. For these countries, commodity

import price rises tend to lead to exchange rate depreciations and

so to more inflation. is approach implies that results capture

mainly the impact of imported inflation shocks, which may differ

from domestically driven shocks affecting the GDP deflator more

directly. See Online Annex 2.2 for details.

Debt/GDP > 50 percent

Debt/GDP ≤ 50 percent

All countries in the sample

Figure 2.2. Reaction to a 1 Percentage Point Growth Spike in the GDP Deflator

(Percent of GDP)

1. Debt

–1.2

–0.8

–0.4

0.0

0.4

–1 0 1 2 3 4 5

Year after shock

2. Overall Balance

–1.2

–0.8

–0.4

0.0

0.4

–1 0 1 2 3 4 5

Year after shock

Source: IMF staff estimates using data from the IMF Public Finances in Modern History and World Economic Outlook databases.

Note: The data cover the period 1962–2019. Fixed effects ordina

ry least squares regressions use the GDP deflator as the inflation indicator and include 85 countries.

Countries with populations of less than 1 million in 2019 are e

xcluded as well as observations with annual GDP deflator inflatio

n higher than 30 percent in absolute terms or

for which the original data source changes. The panels plot the

average impulse response and the 90 percent confidence bands, with standard errors clustered at the

country level. Average debt to GDP in the sample is approximately 50 percent. See Online Annex 2.2.

FISCAL MONITOR: ON THE PATH TO POLICY NORMALIZATION

6 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

Debt/GDP > 50 percent

Debt/GDP ≤ 50 percent

Figure 2.3. Debt Reaction to Surprise versus Expected Growth Spikes in the GDP Deflator

(Percent of GDP)

–1.2

–0.6

0.0

0.6

1.2

–1.2

–0.6

0.0

0.6

1.2

1. Surprise 2. Expected

–1 0 1 2 3 4 5

Year after shock

–1 0 1 2 3 4 5

Year after shock

Source: IMF staff estimates using data from the IMF Public Finances in Modern History and World Economic Outlook databases.

Note: Fixed effects ordinary least squares regressions include 85 countries during the period with available data 1992–2019. Countries with population of less than 1 million

in 2019 are excluded as well as observations with annual surpri

se or expected inflation higher than 30 percent in absolute terms or for which the original data source

changes. Expected inflation is defined as the one-year-ahead fore

cast; surprise inflation is realized minus expected inflation. The panels plot the average impulse response

and the 90 percent confidence bands (blue shaded areas and red short-dashed lines), with standard errors clustered at the country level. See Online Annex 2.2 for details.

–1.2

–0.8

0.0

–0.4

0.4

0.8

1.2

–1.2

–0.8

0.0

–0.4

0.4

0.8

1.2

–1.2

–0.8

0.0

–0.4

0.4

0.8

1.2

1. CPI Inflation

(Percent)

2. Overall Balance 3. Total Tax Revenue

–1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 –1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Quarter after shock Quarter after shock

–1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Quarter after shock

–1.2

–0.8

0.0

–0.4

0.4

0.8

1.2

–0.6

–0.4

0.0

–0.2

0.2

0.4

0.6

–0.6

–0.4

0.0

–0.2

0.2

0.4

0.6

4. Primary Expenditure 5. Interest Expense 6. Nominal Long-Term Bond Rate

(Percent)

–1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Quarter after shock

–1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Quarter after shock

–1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Quarter after shock

Sources: IMF staff estimates using data from Gruss and Kebhaj (2019); Ilzetzki, Reinhart, and Rogoff (2019); and IMF Internatio

nal Financial Statistics and World Economic

Outlook databases.

Note: Regressions are estimated between the first quarter of 199

9 and the fourth quarter of 2019 using instrumental variables a

nd control for quarter indicator variables and

country and year fixed effects (fixed effects two-stage least squ

ares). The panels plot the average impulse response and the 90 percent confidence bands (blue shaded

area) with standard errors clustered at the country level. See Online Annex 2.2 for details. CPI = Consumer Price Index.

Figure 2.4. Estimated Initial Gains to Fiscal Balances from CPI Inflation Spikes

(Percent of GDP, unless stated otherwise)

CHAPTER 2 INFLATION AND DISINFLATION: WHAT ROLE FOR FISCAL POLICY?

7International Monetary Fund | April 2023

finance before policies have time to react. e findings

suggest that for each 1 percentage point initial increase

in inflation, budget balances go up by 0.5 percent

of GDP. Revenue broadly rises in line with nominal

GDP, whereas primary expenditures tend to be stable

in nominal terms in initial quarters. Interest expense

climbs gradually over time given that debt in the

sample features mainly fixed rates and long maturities,

slowing the pickup in effective nominal rates of

public bonds.

e quarterly data further enable empirical

exercises for budget subcomponents, revealing

different patterns among them (see Online

Annex 2.2). While total tax revenue in nominal

terms grows by about the same magnitude as

inflation, some items (profit and income taxes)

rise proportionally more. On the expenditure side,

some expenditure categories are sticky, especially

compensation of employees and social benefits. Over

time, automatic or de facto indexation brings those

expenditures back to their initial levels in real terms.

Distributive Effects of Inflation and

Fiscal Policy Support

Beyond the overall impact of inflation on the

fiscal accounts, analyzing the effects of inflation on

the distribution of households’ well-being is key

to understanding how policies, including social

protection, can be designed to take such effects into

consideration. Such an analysis can also be useful

for exploring the political feasibility of other policies

or reforms by identifying potential pressure points

(relative winners and losers among those who stand

to gain or lose from inflation). As the discussion that

follows shows, for example, the impact of inflation

in countries with sizable mortgage markets is more

adverse—as a share of household income—for those

older than age 65 (usually net holders of nominal

assets) than for people in their 30s to 40s (who often

have mortgage debt outstanding). When considering

the design, timing, and preparatory work for reforms

to pensions or health care, it would be helpful to

consider that inflation is already placing a burden

on the households and groups that would be more

affected. is section uses household-level data for

distinct countries and economic groups to examine

such distributive effects.

Channels for Distributive Effects of Inflation

across Households

Inflation affects the distribution of households’

well-being through three main channels:

11

• Differences in price increases across goods combined

with differing consumption patterns (consumption

basket channel). If the prices of some goods rise

more than those of others, households with a higher

share of higher-priced goods in their consumption

baskets will suffer more. For example, spikes in food

prices may hurt the consumption of the poor more

than other households because food constitutes a

larger share of consumption (and income) for the

poor (Baez Ramirez, Inan, and Nebiler 2021). If

inflation becomes equally widespread across goods

and services, this differential effect abates.

• Impact on households’ real incomes (income channel).

Real incomes may be significantly eroded if wages,

pensions, or other transfers do not keep pace with

inflation. The extent and distribution of such erosion

depends not only on features of the labor market and

pension or transfer systems but also on the source of

price changes. During the price surge of 2021, which

was driven by commodity prices, for example, real

wages fell in most commodity-importing countries

but rose in some commodity-exporting countries.

In some historical episodes during which inflation

originated from a worker-led push for compensation,

real wages may have risen.

12

Moreover, if price and

wage changes stem from the sudden emergence

of imbalances in demand and supply for certain

sectors or skills, some workers may benefit (or be

harmed) disproportionately. Likewise, wage and

pension indexation may serve some workers or

retirees to the detriment of others (Süssmuth and

Wieschemeyer 2022).

• Impact on the real value of households’ initial stock

of assets and liabilities (wealth channel). Inflation

is expected to lead to a change in relative asset

prices and a reduction in real terms of households’

11

See also Online Annex 2.3 and Cardoso and others (2022). e

term “well-being” is a shorthand for the sum of these three effects.

e analysis does not estimate welfare using utility functions, nor

does it consider households’ behavioral responses.

12

According to Hirschman (1985, 60), the experience in Argentina

in 1946–55 could be interpreted as an attempt at redistribution

toward lower-income groups through higher wages, social security,

and transfers, which were also associated with higher inflation.

FISCAL MONITOR: ON THE PATH TO POLICY NORMALIZATION

8 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

initial liabilities. A surprise hike in inflation in

principle helps net borrowers and hurts net lenders

(Doepke and Schneider 2006). In countries featuring

developed financial and credit markets, wealth effects

are potentially relevant. The change in relative asset

prices means that portfolio composition also matters.

Families holding cash as their main asset tend to be hit

the most (Albanesi 2007). Likewise, holders of bank

deposits and fixed-rate government bonds usually

incur real losses from inflation. Instead, historically,

home or land ownership has served as good protection

against inflation, and mortgage borrowers have often

benefited from it (Box 2.2).

Estimation

e effects through these three channels are

estimated for six economies, using a new rich set

of statistics and household survey data. e sample

encompasses low-income and developing countries

(Kenya and Senegal ), emerging market economies

(Colombia and Mexico), and advanced economies

(Finland and France). ese countries also vary with

respect to past inflation histories, status as commodity

exporters or importers, and availability and use of

mortgage and other household credit markets. e

wealth channel is estimated only for Colombia,

Finland, and France, given data constraints.

To illustrate, the analysis focuses on observed

price developments during the initial upsurge in

global prices in the aftermath of the COVID-19

pandemic; that is, the second quarter of 2021 to the

second quarter of 2022. is rise was concentrated

in food and energy prices and was associated with a

cost-of-living crisis for millions of people across the

world. All countries in the sample faced significant

headline inflation, ranging from 6.1 percent in

France to 9.2 percent in Colombia during the period

considered. Prices of food spiked the least in Finland

and France, whereas energy prices in those countries

rose the most (Online Annex 2.3).

13

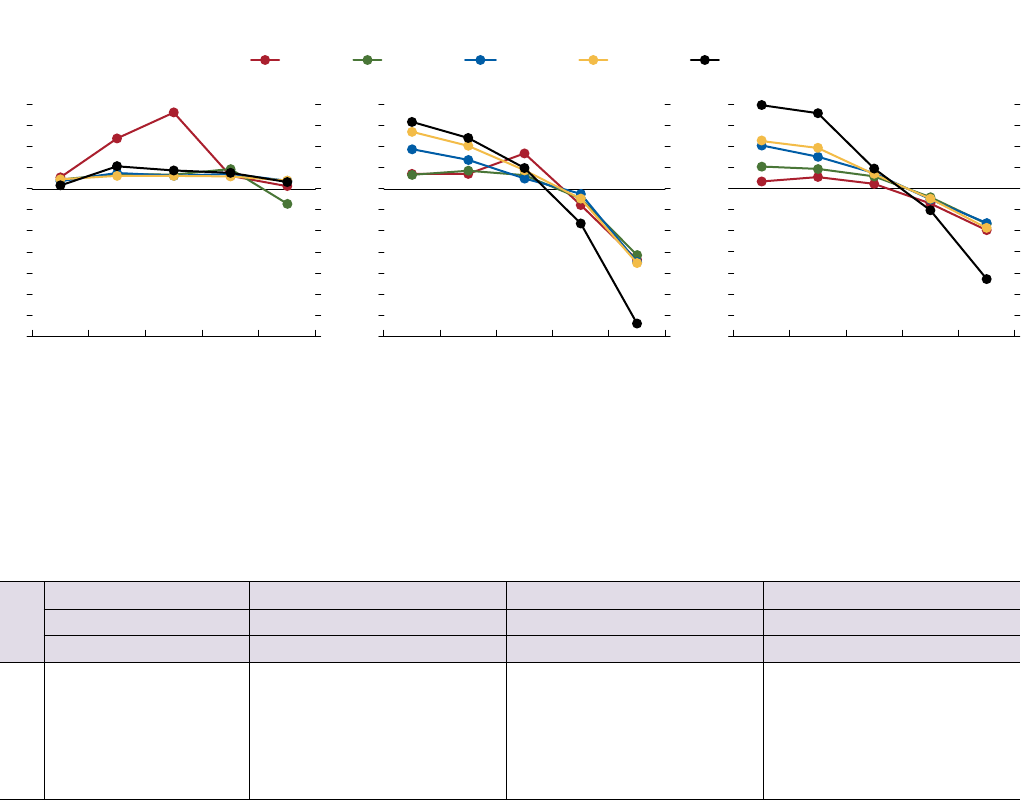

e consumption basket channel is illustrated by

reporting averages, by quintile, of household-specific

inflation and the contributions of various

components of household consumption baskets

(food and nonalcoholic beverages; housing, water,

13

See Online Annex 2.3 for the details, including the assumptions

for the income and wealth estimates. Online Annex 2.3 further

analyzes total net wealth, including real assets, such as dwellings.

electricity, gas, and other fuels; transportation; other)

for the second quarter of 2021 to the second quarter

of 2022 (Figure 2.5). A household’s specific inflation

is the weighted average of the percentage price

hikes (in each country) for each given consumption

category, with the weights derived from the individual

household’s consumption basket as reported in

the survey.

Household-specific inflation levels are higher for

households in lower income quintiles in Colombia,

Kenya, Mexico, and Senegal, reflecting a larger

contribution from food price increases for the lower

quintiles (Figure 2.5). In turn, this stemmed from a

combination of (1) more rapid increases in food prices

than in other goods and (2) the well-known universal

pattern whereby the share of food in total consumption

declines with income per person.

14

For Finland and

France, household-specific inflation rates are nearly the

same across income quintiles. In these two countries,

the contribution from food prices was limited because

the rise in food prices was less pronounced, and food

accounts for a share of consumption that is lower and

roughly the same across quintiles. Energy prices rose

faster and account for a sizable portion of the overall

increase, although the effect was felt through utilities

at the lower quintiles and transportation (which

includes fuel) at the higher quintiles.

15

More recently,

energy prices have adjusted down to levels seen before

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (see Chapter 1), and these

consumption basket channels may abate or even reverse.

However, as found in new evidence reported in Box 2.3,

changes in relative prices can on occasion persist or

widen for several years, with meaningful implications for

the budgets of different groups.

Although the effects occurring through the

consumption basket channel were sizable during the

period analyzed, they may become negligible (or

reverse) when other sample periods are considered that

14

In developing or emerging market economies such as

Colombia, Kenya, Mexico, and Senegal, the poorest households

spend 40–50 percent of their budget on food, compared with

15–30 percent for their richest quintiles. In advanced economies

such as Finland and France, the budget share spent on food is

roughly constant across quintiles at 10–15 percent. In the United

States too, transportation represents a large expenditure share for the

middle/upper class (e Economist 2023).

15

Whereas energy used for utilities in these countries is a larger

share of consumption for lower-income households, the share of

transportation in total consumption rises with household income

(see Hellebrandt and Mauro 2015 for international evidence).

CHAPTER 2 INFLATION AND DISINFLATION: WHAT ROLE FOR FISCAL POLICY?

9International Monetary Fund | April 2023

encompass, for example, food price increases similar to

(or lower than) the general price index.

16

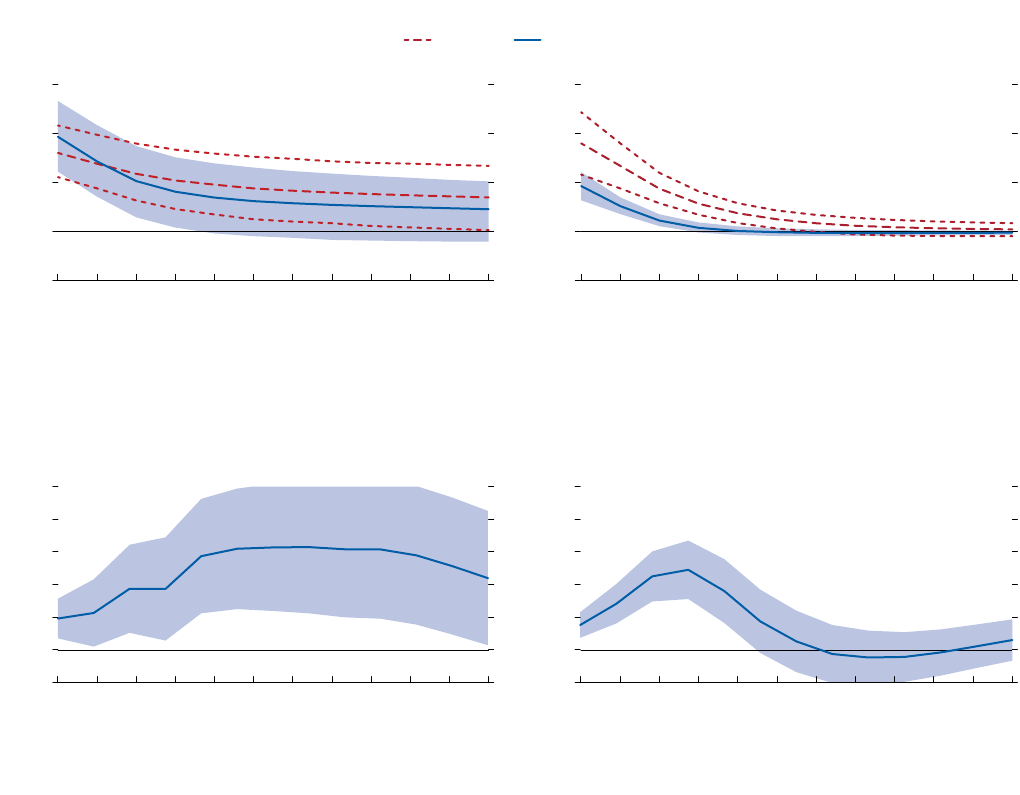

Whereas the consumption basket channel

appropriately received much attention in several

recent analyses,

17

the other two channels often have

had even greater impacts. e income channel was

generally the most prominent, but its sign differed

across countries (Figure 2.6, blue bars).

18

In Finland,

France, Kenya, and Senegal, nominal changes in

remuneration of families through wages, pensions,

16

In all countries except Finland, the consumption channel is

negative at the bottom of the income distribution and positive at the

top. e finding confirms the evidence shown above on the cost of

living in Colombia, Kenya, Mexico, and Senegal increasing more for

poor households than for rich households.

17

See, for example, OECD (2022b) for Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development economies;

Charalampakis and others (2022), Claeys and Guetta-Jeanrenaud

(2022), and Mohrle and Wollmershauser (2021) for European

countries; and Autor, Dube, and McGrew (forthcoming), Jaravel

(2022), and US CBO (2022c) for the United States.

18

Figure 2.6 assumes changes in nominal values of incomes, assets,

and liabilities in line with the data discussed in Online Annex 2.3.

e annex includes another simulation in which those financial

resources are assumed to remain constant in nominal terms, allowing

for a study of the immediate effects of an unexpected inflationary

shock. In that scenario, the total immediate effects of inflation on

households’ incomes are negative in all countries, with the fall in real

income being equal to the level of inflation.

and other income failed to keep pace with price

hikes. In Colombia and Mexico, real incomes rose. e

fact that these two countries are oil exporters may

explain why nominal income increased there more

recently. Institutional factors may be at play too—for

example, wage and pension indexation is widespread

in Colombia and Mexico. In most countries, the

impact of inflation via this channel did not vary

much across quintiles and, to the extent it did, there

was no clear pattern, with several characteristics

playing important roles (including the gender of the

head of household; Mao 2022).

Effects occurring through the wealth channel are

also significant in the countries for which data are

available (Figure 2.6, green bars) and present the most

complex interactions with household income, age

of the head of the household, and country-specific

mortgage and household credit markets.

19

In Finland

and France, real losses from the erosion of net nominal

assets (or gains from erosion of net nominal liabilities)

19

Emerging market and advanced economies generally have

more developed financial markets and higher household debt levels

(Bahadir and Gumus 2016; Jordà, Schularick, and Taylor 2016).

Credit for large real assets, such as dwellings, is less widespread in

low-income countries. For an analysis of the penetration of mortgage

loans in those economies, see Badev and others (2014).

Other consumption categories

Transport Housing, water, electricity, gas, and other fuels Food and nonalcoholic beverages Annual inflation

Figure 2.5. Household-Specific Levels of Inflation per Quintile, 2021−22

(Percent)

1. Kenya

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

2. Mexico

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

3. Senegal

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

4. Colombia

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

5. Finland

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

6. France

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: The figure covers the period from the second quarter of 20

21 to the second quarter of 2022. In Colombia and Mexico, and in Finland and France, quintiles are built

using per capita income. For Kenya and Senegal, the quintiles use per capita consumption (as a proxy for their income). See Online Annex 2.3 for details.

FISCAL MONITOR: ON THE PATH TO POLICY NORMALIZATION

10 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

differ significantly across household income groups.

Families in the fourth quintile in Finland and the

third and fourth quintiles in France are, on average,

net borrowers (at least in terms of liquid assets and

liabilities) and thus experience net wealth gains from

inflation.

20

Conversely, families in the two lowest

quintiles in Finland and, to a lesser extent, those in the

lowest and highest quintiles in France are net lenders

(or holders of net nominal assets) and experience

losses. In Colombia, households for all income groups

report, on average, that they have net liquid liability

positions.

21

e positive size of the wealth effect is

significant, in comparison with the other effects, and

does not present a straightforward association with

income—the largest gains are for the lowest and

highest income quintiles.

20

e conclusions may depend on whether real assets, including

dwellings, are considered (see Online Annex 2.3).

21

Although this would merit further analysis, the asset counterpart

to these positions could be with financial institutions (including

informal ones). e survey does not include information about

ownership of these assets.

Considering the overall impact of inflation and the

relative importance of the three channels (consumption

basket, income, and wealth) in different countries and

for different income groups, it becomes apparent that

the impact of inflation on well-being is variegated and

depends on several factors. In Kenya, during the period

considered, the impact of inflation was worse the lower

the income group, largely owing to the stronger impact

of food prices on the poor. e pattern is similar,

though less pronounced, in Mexico, whereas in Senegal,

the income channel drove most of the action, with

little variation across quintiles. In Colombia, the overall

impact of inflation was similar across income quintiles,

as the income and wealth channels masked the pattern

stemming from the consumption basket channel. In

Finland and France, the middle quintiles were less

affected than the highest and lowest. While the income

channel was the most sizable, variation across quintiles

reflected the wealth channel.

22

22

For inequality trends by income percentile in the United States

caused by inflation see Autor, Dube, and McGrew (forthcoming).

Income Consumption Total Income Consumption Total Income Consumption Total

Income

Wealth

Consumption

Total

Income

Wealth

Consumption

Total

Income

Wealth

Consumption

Total

Figure 2.6. Income, Consumption, and Wealth Channels, 2021−22

(Percent of household income)

1. Kenya

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

8

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

2. Mexico

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

8

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

8

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

3. Senegal

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

8

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

8

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

4. Colombia

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

8

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

5. Finland

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

6. France

Poorest 2 3 4 Richest

Source: IMF staff calculations, as described in Online Annex 2.3.

Note: The figure covers the period from the second quarter of 20

21 to the second quarter of 2022. For Colombia, results are based on the financial inclusion module of the

Great Integrated Household Survey (GEIH) to include the wealth effect. Results for income and consumption basket channels using a representative survey are similar.

CHAPTER 2 INFLATION AND DISINFLATION: WHAT ROLE FOR FISCAL POLICY?

11International Monetary Fund | April 2023

Redistributive wealth effects of inflation are

also strongly influenced by the age of the head of

household, especially in countries with sizable markets

for mortgages. Figure 2.7 shows that for Finland and

France, young families, which tend to be net borrowers

(for example, via mortgages), experience gains through

the wealth channel. For most families, a mortgage is

the largest loan they ever undertake to gain ownership

of their largest asset—their home. In contrast, older

age groups, which typically do not have mortgages

and are net holders of nominal assets, experience

wealth erosion. is pattern holds within each income

quintile and in these countries is most pronounced

within the highest income quintile, which has the

easiest access to credit and asset markets. No clear

pattern is identified in Colombia, however. To sum

up, in advanced economies, a group highly exposed

to losses from inflation would consist of retirees who

live in a rental apartment and hold their savings in

nominal assets and whose pension is not indexed.

e importance of age is further corroborated

by results for Spain by Cardoso and others (2022).

Table 2.1 compares their results with those in

this chapter.

Poverty

e analysis further suggests a likely increase in

poverty in all economies analyzed. Figure 2.8 displays

the change in absolute poverty headcount following four

Poorest

p20–p40 p40–p60 p60–p80 Richest

Figure 2.7. Wealth Effect by Age and Income Brackets, 2021−22

(Percent of household income)

–21

–18

–15

–12

–9

–6

–3

0

3

6

9

12

–21

–18

–15

–12

–9

–6

–3

0

3

6

9

12

–21

–18

–15

–12

–9

–6

–3

0

3

6

9

12

<36 36–45 46–55 56–65 >65

Age of the head of household

<36 36–45 46–55 56–65 >65

Age of the head of household

<36 36–45 46–55 56–65 >65

Age of the head of household

1. Colombia 2. Finland 3. France

Source: IMF staff calculations, as described in Online Annex 2.3.

Note: The figure covers the period from the second quarter of 20

21 to the second quarter of 2022. Each line in the panels corresponds to the income brackets. The wealth

effect differs, on average, across generations: Young people ar

e net borrowers, whereas elderly people tend to be net lenders. Therefore, the wealth effect is usually

positive for young people and negative for older households. p = percentile.

Table 2.1. Total Effect of Inflation on Saving Capacity by Age-Income Groups

(Percent of household income)

Age

Spain Colombia Finland France

Income Quartile Income Quintile Income Quintile Income Quintile

Poorest Second Third Richest Poorest Second Third Fourth Richest Poorest Second Third Fourth Richest Poorest Second Third Fourth Richest

<36 –2.6 –2.9 –2.4 –2.9 9.0 –8.4 –8.1 –7.4 –7.7 –6.2 –6.1 –2.8 0.1 1.6 –5.1 –3.1 0.2 0.9 6.0

36–45 –0.9 –0.3 –1.0 –2.0 –3.4 –8.0 –7.2 –7.1 –5.0 –5.8 –5.5 –3.7 –1.7 –0.7 –4.3 –3.0 –1.2 0.1 5.0

46–55 –3.5 –3.5 –3.9 –4.4 –0.7 –8.5 –8.2 –7.5 –5.7 –3.3 –6.0 –6.6 –5.3 –4.9 –5.2 –4.1 –3.7 –3.8 –2.9

56–65 –8.3 –6.2 –6.9 –6.8 –10.1 –7.6 –8.1 –7.6 –6.2 –10.4 –9.3 –8.7 –9.3 –12.9 –7.8 –6.9 –7.3 –7.1 –8.9

>65 –12.7 –9.6 –9.8 –9.7 –11.3 –13.0 –9.1 –8.4 –7.8 –17.3 –16.9 –18.2 –18.2 –27.0 –11.2 –10.4 –10.4 –11.2 –18.5

Sources: Cardoso and others (2022) for Spain and IMF staff calculations for Colombia, Finland, and France.

Note: Age brackets are based on the age of the head of household. See Online Annex 2.3 for details.

FISCAL MONITOR: ON THE PATH TO POLICY NORMALIZATION

12 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

scenarios of price hikes:

23

(1) baseline or actual inflation

(and distribution across goods and services) in each

country from the second quarter of 2021 to the second

quarter of 2022, (2) an average or widespread price hike

in all goods and services, whose increase remains equal

to the country’s inflation level, (3) a 5 percent hike in

the price of food and nonalcoholic beverages on top of

observed price rises, and (4) a 5 percent spike in energy

prices on top of observed price rises.

e estimated impact of inflation (observed baseline)

on the poverty rate, prior to new compensatory

measures, is as high as about 1 percentage point in

France, Mexico, and Senegal. Such increases in poverty

already consider the growth of nominal income, which

helped contain the adverse effects of inflation on

poverty. In the countries studied, the mitigating effect

of the growth in nominal income on poverty varies,

with some countries experiencing little to no effect,

while others, like Colombia, experienced a significant

reduction in the poverty headcount (0.4 percentage

point). Rises in food prices had a disproportionate

impact on vulnerable populations during the period

23

Poverty headcount is the share of the population whose income

falls below international poverty lines set by the World Bank.

considered. e effect of a rise in food prices is larger

in Kenya, Senegal, and Mexico, whereas energy price

hikes are more important for Colombia, Finland, and

France. If the pace of increases in food and energy

prices declines below average consumer price inflation, a

significant source of increases in poverty may subside.

Disinflating and Distributing

e previous sections show how inflation affects

public finances and households. Now the analysis

turns to whether and how fiscal policy affects

inflation. Understanding the specific channels through

which public policies affect inflation and how those

policies can contribute to the mix of instruments

meant to restore price stability are two complex and

interconnected issues. Monetary and fiscal policies

have their own distributional effects. In addition, their

overall impacts on the macroeconomy vary according to

the structure of wealth and income inequality. Recent

studies (often using a so-called Heterogeneous Agent

New Keynesian [HANK] approach) have indicated that

the role played by fiscal policy in aggregate demand

and inflation management may be larger than typically

assumed. ese studies have also considered monetary

policy’s possible effect on distribution.

is section discusses how fiscal policy may lead to,

or may help deal with, moderately high inflation. It

does not speak to cases of instability, such as episodes

of debt distress, which currently apply to a small set of

emerging markets. Situations in which the government

does not adjust the primary balance to stabilize public

debt and central banks are less independent—both

usually associated with the economic concept of fiscal

dominance—are outside the scope of this chapter.

24

Instead, the standard assumption that central banks

pursue their objective of price stability, unhindered

by concerns about public debt, holds. Public finances

matter for inflation via their impact on aggregate

demand.

25

ey also contribute to the price stability

goal if they are aligned with monetary policy, bringing

credibility to the overall macroeconomic framework.

Hence, by taming spending, governments can help

monetary policy curb inflation at lower costs for the

24

See Leeper (1991), Sims (1994), and Cochrane (1998), who

initially developed the Fiscal eory of the Price Level.

25

Over time, such effects of fiscal policy can be offset by monetary

policy through the rise in interest rates.

Baseline inflation

Average inflation

5% higher food prices

5% higher fuel prices

Figure 2.8. Changes in Poverty from Different Types of Price

Increase Shocks (Excluding New Policy Measures

Responding to Inflation)

(Percentage points)

–0.2

0.6

0.8

2.0

0.0

0.2

0.4

1.6

1.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

Kenya SenegalColombia MexicoFranceFinland

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: Baseline inflation refers to household inflation calculated

based on observed

inflation from the first quarter of 2021 to the second quarter of

2022. Results can

be considered as a ceiling because the estimation does not take

into account new

measures taken by the government or households to respond to th

e effects of

inflation.

CHAPTER 2 INFLATION AND DISINFLATION: WHAT ROLE FOR FISCAL POLICY?

13International Monetary Fund | April 2023

overall economy (see, for example, Adrian and Gaspar

2022; and Erceg and Lindé 2012).

Fiscal policy support for monetary policy in

disinflating is important for two additional reasons.

First, monetary tightening

26

can have unwelcome

distributive effects—for example, via more expensive

credit for small firms (Alfaro, Faia, and Minoiu 2022;

Haltom 2012) and because the poor do not hold

interest-bearing assets.

27

Second, a disinflation strategy

that relies solely on monetary policy is accompanied

by real interest rates that are too high, and this can

pose a challenge for debt dynamics. Government

policies, in turn, can be more agile and contemplate

other objectives if the right fiscal tool is employed.

28

Different fiscal policies can be calibrated and used to

support the disinflation effort while mitigating the

increase in poverty and income inequality at the same

time. Monetary policy does not have the mandate to

address income inequality, nor can it be targeted in the

way that fiscal policy can.

In effect, the discussion in this chapter is

geared toward policies that can help reduce overall

inflationary pressures while providing temporary

support (preferably targeted cash transfers) to the most

vulnerable. It does not advocate the use of specific

fiscal instruments to cap specific prices. As during the

recent episode, some countries have adopted price

controls or subsidies, put the squeeze on profits of

state-owned enterprises, or cut taxes to try limit price

increases and inflation (see Chapter 1 and the October

2022 Fiscal Monitor). However, such actions can be

costly to the budget, lead to shortages and rationing,

and prove ultimately ineffective and potentially make

inflation more persistent.

26

In the analysis, monetary tightening is captured by central

banks’ hikes in interest rates. However, in the current inflationary

episode, many central banks—which have used quantitative

easing to support firms and households during the recent years

of very low interest rates and the pandemic—may also restrict

their policies through quantitative tightening. For example, some

monetary authorities may stop purchasing corporate bonds, which

was guaranteeing a supply of liquidity for some firms. Other

central banks may even consider selling a portion of the corporate

bonds they hold on their balance sheets. While those policies

may have implications for (dis)inflation, they are not considered

explicitly in this chapter’s exercises.

27

Yet low interest rates are also shown to inflate stock prices,

benefiting the rich (Auclert 2019), so a monetary tightening may

have the opposite effect, depending on country characteristics.

28

Public investment projects, for instance, have long lags of

execution that are usually higher than those of monetary policy.

Historical Evidence of the Impact of Fiscal Policy

on Inflation

To assess the effect of public spending on inflation,

as motivated by the recent spending surge, for a broad

sample of economies, an empirical analysis is pursued

using historical data from 1950 for 17 advanced

economies, for two periods: 1950–85 and 1986–2019.

e split in 1985 is aimed at dividing the sample into

an earlier period of relatively passive monetary policy in

advanced economies and a later period of more active

monetary policy that anchors inflation expectations

(see Banerjee and others 2022). e analysis focuses on

public spending given that the recent debate relates to

the large spending surge during COVID-19 (Gopinath

2022), as during the two world wars (Box 2.4).

e analysis shows that the effect of public

spending on inflation varied over time (Figure 2.9). A

1 percent-of-GDP rise in government spending in the

pre-1985 period leads to an average hike in inflation

of almost 1 percentage point in the same year, phasing

out slowly. For the post-1985 period, the same shock

leads to an average increase in inflation of roughly half

that size and, differently from the first case, it flattens

out after three to four years. Monetary policy responses

to forces pushing inflation up in both periods varied

markedly. In the earlier part of the sample, central banks

were more likely to accommodate fiscal expansions,

thus allowing for a higher pass-through from those

expansions to inflation. After 1985, central banks more

often tightened monetary policy in response to fiscal

expansions to slake their inflationary effects.

Ascertaining a causal impact of public spending

on inflation (rather than vice versa, or the impact of

a third factor on both variables) involves the same

thorny methodological challenges faced by studies that

have sought to estimate the fiscal multiplier for output

(Ramey 2019; April 2012 Fiscal Monitor, Chapter 1).

Following Ramey and Zubairy (2018), this chapter

analyzes increases in government purchases that follow

news about extra military spending in the United States.

e methodological advantage is that such news is not

caused by the economic cycle, and the only impact on

the US economy occurs through additional spending.

29

As shown in Figure 2.10, there is a clear positive effect

29

Specifically, a structural vector autoregression model is

estimated, with public spending identified by quarterly news of

additional military spending in the United States from the first

quarter of 1939 to the fourth quarter of 2015 (Ramey and Zubairy

2018). See Online Annex 2.4.

FISCAL MONITOR: ON THE PATH TO POLICY NORMALIZATION

14 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

on inflation. As the blue line in panel 1 indicates,

following the news of additional military spending,

output increases in subsequent quarters, confirming

the presence of a positive fiscal multiplier (see Online

Annex 2.4). e novel result is the response of annual

inflation: It rises and reaches the highest level in less

than one year after the spending news, with inflation

going up by an additional 0.5 percentage point

than otherwise.

Fiscal Policy and Disinflation: Lessons from an

Economic Model with Income Distribution

To illustrate and understand some of the main

consequences of varied monetary-fiscal mixes, the

analysis turns to a (simple) version of a state-of-art

class of models that include a richer description of

the households’ income and wealth distribution—the

HANK model (McKay and Reis 2016; Kaplan, Moll,

and Violante 2018; Bayer, Born, and Luetticke 2023).

Such a model allows for the impact of different types

of public policies—fiscal and monetary—on the

households’ income distribution. Specifically, the analysis

here focuses on how different forms of fiscal restraint

by the government can help monetary policy achieve

price stabilization. At the same time, their distributive

effects across households are analyzed and considered for

policy design.

e model has five crucial ingredients: (1) e

government issues short-term debt that is held mostly

by the higher-income groups; (2) when debt rises above

90 percent of GDP, taxes are gradually increased to

guarantee that debt returns to that value; (3) transfers

for lower-income people boost overall private

1986–20191950–85

1. Output

Percent

2. Inflation

Sources: IMF staff analysis using the IMF Public Finances in Modern History database; and Jordà, Schularick, and Taylor (2017).

Note: The panels plot average impulse responses and the 90 perc

ent confidence bands (shaded blue area and short-dashed lines). See Online Annex 2.4 for further details.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Years

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Years

Percentage points

–0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

–0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

Figure 2.9. Panel Evidence of the Fiscal Policy Impact on Inflation, 1950–2019

Figure 2.10. Fiscal Policy Impact on Inflation in the United States, 1939−2015

1. Impulse Response for Output

Percent

2. Impulse Response for Inflation

Sources: IMF staff estimates using the Ramey and Zubairy (2018) database; and IMF World Economic Outlook database.

Note: The figure covers the period from the first quarter of 1939

to the fourth quarter of 2015. The panels plot the average impulse responses (solid blue line) and the

90 percent

confidence bands (blue shaded areas). See Online Annex 2.4.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Quarter after shock

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Quarter after shock

Percentage points

–0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

–0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

CHAPTER 2 INFLATION AND DISINFLATION: WHAT ROLE FOR FISCAL POLICY?

15International Monetary Fund | April 2023

consumption because these groups consume a high

share of any extra dollar of income they receive; (4) the

central bank increases real interest rates when inflation

goes above target (specifically, the central bank follows

a so-called Taylor rule); and (5) taxes on labor income

are progressive, meaning that higher-income families pay

a higher share of their income in taxes, compared with

lower-income families.

30

Calibrating the model for the United States

(Auclert and others 2021), the analysis examines three

combinations of policies to reduce inflation: (1) an

increase in the nominal interest rate above what the

Taylor rule would suggest, with fiscal policy taking

no further action than required for a gradual return

30

In this version of model, the production function includes labor

and a productivity term but not capital.

to its debt target (90 percent); (2) untargeted fiscal

tightening—that is, a reduction in overall spending

across all budget items; and (3) targeted fiscal

tightening composed of an overall cut in spending

items while increasing transfers to families in the

lowest 10 percent of the income distribution.

In the first scenario, nominal interest rates are

raised by 250 basis points to bring inflation down by

about 2 percent in roughly two years (Figure 2.11).

Output and consumption fall throughout this period.

e poorest families cut their consumption the most

because they have no assets to draw from.

e second scenario simulates a cut in overall public

spending amounting to 1 percent of GDP while

monetary policy is also actively following a Taylor

rule. is leads again to a contraction in aggregate

demand and output, with inflation falling by a total of

Inflation

(percentage points)

Consumption

GDP

99 (richest)

90–100

65–90 35–65

10–35 1–10

1 (poorest)

Inflation

(percentage points)

Consumption

GDP (right scale)

Inflation

(percentage points)

Consumption

GDP (right scale)

Figure 2.11. Disinflating via Different Policy Tightening Options in the HANK Model

(Deviation from long-term value)

Variation in Interest Rates

(Percentage points)

1. Monetary Tightening

Impact on Inflation,

Consumption, and Output

(Percent, unless stated otherwise)

Consumption by Income Bracket Percentile

(Percent)

0 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 116 8 10 12 0 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 116 8 10 12 0 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 116 8 10

12

0 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 116 8 10

12

0 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 116 8 10

12

0 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 116 8 10 12

0 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 116 8 10 12

–1.0

–0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

–1.8

–1.2

–1.5

–0.9

–0.6

–0.3

0.0

0.3

0.6

0.9

–0.8

–0.6

–0.4

–0.2

0.0

2. Fiscal Restraint Only

0 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 116 8 10 12

0 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 116 8 10 12

–1.0

–0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

–1.8

–1.2

–1.5

–0.9

–0.6

–0.3

0.0

0.3

0.6

0.9

–0.8

–0.6

–0.4

–0.2

0.0

–2.0

–1.5

–1.0

–0.5

0.0

Quarter after shock Quarter after shock Quarter after shock

3. Fiscal Restraint with Targeted Transfers

–1.0

–0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

–1.8

–1.2

–1.5

–0.9

–0.6

–0.3

0.0

0.3

0.6

0.9

–0.8

–0.6

–0.4

–0.2

0.0

–2.0

–1.5

–1.0

–0.5

0.0

Source: IMF staff calculations based on the model calibration i

n Auclert and others (2021).

Note: See Online Annex 2.4 for details. HANK = Heterogeneous Ag

ent New Keynesian.

FISCAL MONITOR: ON THE PATH TO POLICY NORMALIZATION

16 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

2 percentage points in eight quarters (as a response the

central bank cuts interest rates, which in the real world

should be interpreted as being able to raise them by

less). e drop in aggregate demand affects everyone,

but the impact is proportionately more cushioned for

higher-income families by the decline in taxation.

In the third scenario, a fiscal tightening of the same

overall size (1 percent of GDP) but with a different

composition is simulated. While the fiscal effort in other

spending items is greater than before (by 1.5 percent of

GDP), targeted transfers to the poorest 10 percent of

families are in turn increased by 0.5 percent of GDP.

e results show that in such a scenario, both GDP and

inflation go down. But because the poor households

receiving transfers consume a high share of their extra

income, aggregate consumption decreases by less than

in the other simulations. e consumption of those

targeted households goes up with the transfers. To

summarize, a generalized fiscal contraction helps contain

inflation, with a smaller drop in private consumption

than in the monetary policy scenario, but its impact

favors higher-income groups at the expense of the

lower-income groups. ese adverse distributional effects

can be remedied if the fiscal contraction is accompanied

by a targeted transfer program.

Conclusions

e evidence presented in this chapter highlights

the pattern that inflationary surprises are historically

associated with an initial rise in fiscal balances in the

short term and a fall in public debt that often persists

into the medium term. However, expected inflation is

not associated with a fall in debt ratios, stressing that

inflating debt away is neither a desirable nor a sustainable

strategy. Unexpected inflation may offer some breathing

room for debt ratios, but attempts to keep surprising

bondholders have historically proved futile or harmful.

e impact on debt is more significant for countries with

large amounts of debt, especially when it is denominated

in local currency, long term, and unindexed. For

countries with debt exceeding 50 percent of GDP,

each 1 percentage point surprise increase in inflation is

estimated to reduce public debt by 0.6 percentage point

of GDP, with the effect lasting for several years.

Current practices on indexation vary considerably

across countries. Among budget items, pensions are

the most commonly indexed, followed by transfers to

lower-income groups and public sector wages. When

reviewing automatic or discretionary indexation going

forward, policymakers need to decide which groups

and programs to protect from income erosion while

avoiding policies that make inflation more persistent.

Policymakers should carefully assess the impact of

public wage setting during periods of high inflation,

including through indexation, on the setting of

private wages. Policymakers also need to consider

potential effects of inflation on the structure of

the tax system.

e redistributive effects of inflation on households

are more complex than usually thought. Analysis of

the recent surge in inflation highlights the importance

of changes in families’ incomes and net assets for the

distributive effect, especially in countries with more

developed financial and credit markets. Policy reforms

should consider the redistribution that inflation

drives from net lenders to net borrowers, usually

associated with old and young families, respectively.

During the period considered, the poverty rate rose by

1 percentage point or more in three countries of the

sample (France, Mexico, Senegal ).

While monetary policy is in the driver’s seat

in the battle against inflation, fiscal policy can

help. Well-targeted fiscal restraint can be designed

to support monetary policy in attaining price

stability while protecting the vulnerable from

the cost-of-living crisis. e chapter documents

the empirical association between fiscal policies

and developments in inflation. Estimates suggest

that 1 percentage point of GDP in additional

public spending resulted in higher inflation by

0.8 percentage point in a sample covering the

1950–85 period and by 0.5 percentage point

thereafter. Moreover, through an economic model

capturing income distribution, the chapter shows

that targeted fiscal restraint—involving tough policy

choices on what budget items to cut and which to

protect or expand—can bring inflation down at lower

cost to aggregate consumption and income inequality

while protecting lower-income families.

CHAPTER 2 INFLATION AND DISINFLATION: WHAT ROLE FOR FISCAL POLICY?

17International Monetary Fund | April 2023

This box explores the interplay between public wages,

private wages, and inflation. Public wage setting needs to

be mindful of developments in prices and private wages to

attract and retain qualified civil servants while avoiding

a wage-price spiral.

Public wage setting is important to attract and

retain qualified civil servants. At the same time, public

wage hikes can increase aggregate demand or influ-

ence wage setting in the broader economy, depending

on labor market institutions (such as the density of

unions or the degree of centralization of bargaining)

and the size of the public sector.

Applying the approach of Abdallah, Coady, and

Jirasavetakul (2023) to an expanded country sample,

this box estimates the effects of public wage spikes on

private wages over the medium term using data from

30 member countries of the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development from the first quarter

of 1990 to the second quarter of 2022. Changes in gov-

ernment wages are assumed to be predetermined with