Community Health Needs Assessment

Suicide Attempt Survivor

Support Resources

in Southeastern Pennsylvania

Tony Salvatore

Montgomery County Emergency Service

Norristown, PA

June 2021

Information presented in this report may be triggering to some people. If this occurs or if

you are having thoughts of suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-

800-273-TALK (8255) or text HOME to 74174 to reach the national Crisis Text Line. Both of

these resources are available 24/7.

You may also call any of the following crisis services in SE PA 24/7:

Bucks County

Lenape Valley Foundation - 800-499-7455

Chester County

Valley Creek Crisis Center - 877-918-2100

Delaware County

Crozer Chester Medical Center Crisis - 610-447-7600

Crisis Connections - 855-889-7827

Montgomery County

MCES - 610-279-6102

ACCESS Mobile Crisis - 1-855-634-HOPE (4673)

Philadelphia County

Northeast Philadelphia - 215-831-2600

Northwest Philadelphia - 215-951-8300

North Philadelphia - 215-707-2577

Center City/South Philadelphia - 215-829-5249

West/Southwest Philadelphia - 215-748-8525

If you or someone that you know is in imminent danger of

attempting suicide call 911 immediately.

CONTENTS

Executive Summary 1

Study Background and Purpose 2

Suicide Incidence in Southeastern Pennsylvania 3

Individuals and Organizations Consulted in Study Planning 4

Role of Suicide Attempt Postvention in Suicide Prevention 5

Suicide Attempts as a Community Health Problem 7

Suicide Attempts are a High Priority Community Health Problem 9

Pertinent Findings from Suicide Attempter Research 11

Study Design and Methodology 12

Suicide Attempt Support Needs Survey 13

Support Resources in Southeastern Pennsylvania 14

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline as a Resource 15

Recommendations 16

Appendix: Selected Resources for Attempt Survivors 17

Appendix: Suicide Attempt Research Bibliography 19

Community Health Needs Assessment

Suicide Attempt Survivor Support Resources in Southeastern Pennsylvania

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Individuals who have made a suicide attempt have the highest risk of dying by a subsequent

suicide attempt. A suicide attempt may occur when an at-risk person develops a strong desire

to die, has a plan and lethal means to bring about his death, and has overcome any protective

factors and the inborn resistance to engage in potentially fatal self-harm. A suicide attempt is a

traumatic event even when it results in little or no self-injury. Those who survive a suicide

attempt need both professional treatment and support in recovering from the attempt and

coping with the stigma, guilt, shame, and other negative sentiments that may follow an

attempt. A significant number of MCES admissions involve individuals who have made or tried

to make a suicide attempt.

MCES undertook an assessment of the availability of support resources in southeastern

Pennsylvania. Only two support groups for persons troubled by suicidal thoughts exist in the

region, one in Bucks County and another in Montgomery County. An online group for suicide

attempt survivors will accept participants from other counties. MCES explored the need for

suicide attempter support with stakeholders in the region and all acknowledged the need as

critical and contributing to ongoing suicide risk. MCES also conducted surveys with inpatients,

Carol’s Place clients, and online. The majority of respondents confirmed the need for suicide

prevention groups in psychiatric hospitals, a 24/7 peer-led warm line for persons dealing with

suicidal thoughts, and the formation of suicide attempter support groups in each county in the

region.

[ 1 ]

STUDY BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

In 2001, the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action included an

objective calling for developing guidelines for aftercare treatment of individuals exhibiting suicidal

behavior. In 2005, the First National Conference for Survivors of Suicide Attempts (SOSAs), Health Care

Professionals, and Clergy and Laity offered these recommendations on enhancing service availability for

persons who had survived suicide attempts:

Key providers of community-based services must include primary and specialized mental

health treatment providers as well as clerics and lay members of faith-based

organizations.

The support and treatment resources we provide to survivors of suicide attempts must

be developed and sustained in ways that provide a stigma-free system of aftercare.

These resources also must focus on integrating SOSAs within a strengthened network of

social and community-based supports. Other resources, such as attempt survivor

support groups, are needed as effective means of mitigating the risk of suicidal

behaviors among those who engage in serial suicide attempts.

These objectives and recommendations have been echoed in many subsequent suicide

prevention plans and calls for action. This includes Pennsylvania Statewide Suicide Prevention

Plan (2020): “Promote care coordination between hospitals, crisis, behavioral health providers,

families, and community settings to support suicide attempt survivors and their families.”

The present study looks at the availability and unavailability of resources in Bucks, Chester,

Delaware, Montgomery, and Philadelphia Counties for persons who have made or tried to

make a suicide attempt. It was undertaken by Montgomery County Emergency Service (MCES)

as a nonprofit psychiatric hospital to satisfy the requirement of the Affordable Care Act to

conduct community health needs assessment identify and prioritize the significant health needs

of the community it serves every three years.

“The most glaring gap in the present system of treating suicide attempters seems to be a lack

of follow-up and continuity of treatment.”

Welu (1977)

“Because attempted suicide is the greatest known risk factor for completed suicide, reducing

suicide attempts is an important public health and clinical goal.”

Olfson, Blanco, Wall, Liu, Saha et al (2017)

[ 2 ]

SUICIDE INCIDENCE IN SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA

Insofar as every suicide fatality involves a suicide attempt, it may be helpful to look at the

incidence of fatal suicide attempts in the region.

As reported by the Pennsylvania Department of Health, there were 9769 deaths in the state in

the five year period 2015 to 2019 in which the cause of death was intentional self-harm or

suicide. For that period, there were an average of 1954 suicides statewide yearly.

Reported suicides in the five-county region of southeastern Pennsylvania for 2015-2019 were as

follows:

County

Total

%

Age Adjusted Rate

Bucks

443

17.7

12.8/100,000

Chester

336

13.4

12/1/100,000

Delaware

379

15.2

12.3/100,000

Montgomery

547

21.9

12.4/100,000

Philadelphia

794

31.8

10.0/100,000

Total

2499

100.0

There are an average of 500 reported suicides per year in the five-county region, which

accounts for about one-fourth of all suicides in the state. More than one-half of the suicide

deaths in the region over the five-year period occurred in Philadelphia and Montgomery

Counties. The former accounted for just under one-third of all suicides in the region; the latter

experience over one-fifth of all regional suicides for the period.

[ 3 ]

INDIVIDUAL AND ORGANIZATIONS CONSULTED IN STUDY PLANNING

MCES sought input on this study from both internal and outside sources. Sources were

contacted in person; by e-mail and telephone on issues such as study scope, data sources, and

questionnaire design. The following individuals provided suggestions or advice.

Individual

Affiliation

Donna Ambrogi, MSN (Ret.)

Eagleville Hospital

Brian Barber, PhD

Montgomery County Emergency Service

Genevieve Bartuski, PsyD

Southwestern Virginia Mental Health Institute

Marina Cooney, MD

Montgomery County Emergency Service

Ruth Deming, MGPGP

New Directions Support Group

Emily Ferris

Magellan Behavioral Health of Pennsylvania

Paul De Marco

Montgomery County Commitment Office

Terri Erbacher, PhD

Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine

Jess Fenchel

Access Services

Abby Grasso

NAMI-Montgomery County

Erin Hewitt

Montgomery Co. Dept. of Health and Human Services

Garra Lloyd-Lester

NY State Suicide Prevention Center

Govan Martin

Suicide Prevention Alliance, Inc.

Dave McKeighan

Chester County Medical Society

Gabriel Nathan

Suicide Prevention Activist/OCD87

Craig Oliver

Penn Foundation

Susan Shannon

Hopeworx, Inc.

Anna Trout, MSW, CPRP

Montgomery Co. Dept. of Health and Human Services

Dese'Rae L. Stage

Suicide Prevention Activist/livethroughthis.org

Moira Tumelty

Access Services

Matthew Wintersteen, PhD

Thomas Jefferson University/Prevent Suicide PA

In addition, the study was discussed at meetings of the following groups:

Managing Agencies for Excellence (MAX) Behavioral Health Committee

Montgomery County Suicide Prevention Task Force

Montgomery County Community Support Program (CSP)

MCES appreciates the cooperation that these individuals provided in planning or carrying out

the study. MCES is solely responsible for the content of this report.

[ 4 ]

ROLE OF ATTEMPT POSTVENTION IN SUICIDE PREVENTION

The public health view of prevention consists of three levels. Primary prevention works to deter

the problem. Secondary prevention works to identify the emerging problem and try to stop its

progression. Tertiary prevention involves treating the problem and deterring its recurrence.

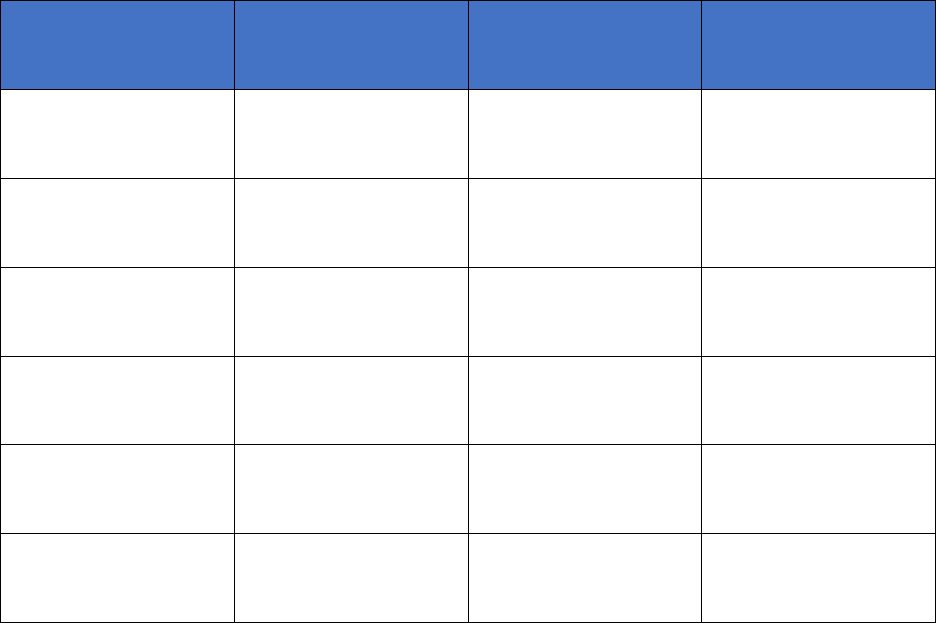

This figure applies the public health model to suicide attempt prevention:

Prevention

Intervention

Postvention

Averting occurrence of a

suicide attempt by:

• Managing specific risk

attempt factors

• Enhancing protective

factors for attempts

Averting suicide attempt

by:

• Identifying and

assessing suicide risk

• Crisis counseling and

referral

Averting suicidality

recurrence by:

• Providing post-attempt

support

• Providing post-attempt

therapy

There is little programming to enhance safety from behavior that may result in a suicide

attempt. Most suicide attempt prevention actually involves direct efforts to dissuade or deter a

person felt to be in imminent danger of making a suicide attempt from doing so. This is most

often accomplished by hot lines, crisis centers, and mobile crisis teams, and police officers. The

last level of suicide prevention is facilitating the recovery of a person experiencing a suicide loss

or surviving a suicide attempt. The latter is known as postvention and is the focus of this study.

Making or trying to make a suicide attempt is a traumatic event. Protective factors have failed,

risk factors are strong, intent to die is severe, a doable plan and lethal means are on hand, and

resistance to potentially fatal self-injury has been overcome. If a suicide attempt does not

proceed, or if it is survived, many of the prerequisites remain. Only intent may subside. Ongoing

suicide risk is very high. Protective factors remain weak. Suicide plans may stay in mind and the

means may continue to be available or accessible. Coming to the brink of ending one’s life r

weakens resistance to do so again if the circumstances fomenting the suicide risk again occur.

An attempt survivor must contend with other issues. The negative life events or problems that

precipitated the progression of the attempt survivor’s suicidality may persist or return.

Stressors such as loss, abuse, chronic illness or pain, disability, substance abuse, mental illness,

financial or housing insecurity, interpersonal conflict, social isolation, and criminal justice

involvement do not subside after a suicide attempt. Feelings of hopelessness, , guilt and shame

that may accrue after a suicide attempt can make the situation worse.

[ 5 ]

Perhaps the most deleterious and compelling impediment to recovery from a suicide attempt is

the stigma the individual may feel from others. While a suicide attempt is often the result of an

individual being overwhelmed by events in her or his life that she or he cannot control and

which have overcome their coping ability, others may see it as selfishness, attention seeking, an

effort at manipulation, or a sign of weakness. In some cases, the self-stigma that may be self-

inflicted. Feelings of stigma may be greater when there have been multiple attempts.

Many suicide attempts result in voluntary or involuntary treatment in a psychiatric inpatient

unit or a psychiatric hospital. An involuntary hospitalization is traumatizing and may cause the

individual to feel angry and betrayed, suspicious of those who might be sources of support, and

less likely to follow the aftercare plan provided at discharge. The days and weeks immediately

after a psychiatric hospitalization, even when not related to suicidality, is a period of high risk

for suicide. This is because the stabilization and safety provided by the hospital are removed

and psychosocial and environmental stressors reassert themselves.

It is the role of postvention to address the challenges that someone contending with the

aftermath of an effort to try to die by suicide or surviving a deliberate suicide attempt.

Postvention can come from various sources and may include:

Information and education about suicide risk and suicide attempts

Self-help and self-care measures to deter the onset of suicidal thoughts

A personal safety plan to use if a suicide crisis occurs

[ 6 ]

SUICIDE ATTEMPTS AS A COMMUNITY HEALTH PROBLEM

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines a suicide attempt as “A non-fatal, self-

directed, potentially injurious behavior with intent to die as a result of the behavior. A suicide attempt

might not result in injury. In 2019, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) found

that 0.6% of adults age 18 and older, 1.4 million persons, in the United States reported they

attempted suicide in in the past year. Among adults across all age groups, the prevalence of

suicide attempt in the past year was highest among young adults 18-25 years old (1.8%).

Among adults age 18 and older, the prevalence of suicide attempts in the past year was highest

among those who report having multiple (two or more) races (1.5%).

A CDC study of 1.2 million “suicidal acts” treated in emergency departments and hospitals

found an increase in incidence of such acts in females and in adults ages 65-74 and an increase

in the lethality of the act in adults ages 20-64 between 2006 and 2015.

The national Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) found that in 2019, 8.9% of youths interviewed

in 9

th

to 12

th

grade made one or more suicide attempts in the twelve months before the survey.

Medical treatment was necessary in 2.5% of the suicide attempts reported by youths in the

survey. The Pennsylvania Youth Survey reported that one in ten youths in the state attempted

suicide in 2017. The American Association for Suicidology (AAS) estimates that there is a suicide

attempt every 26.6 seconds in the United States.

Data for suicide attempts in general is not available at the state or national levels. The Injuries

in Pennsylvania Report issued by the Pennsylvania Department of Health presents the following

data for 2014 (most recent data) for acute hospital discharges for intentional self-injuries, many

of which were suicide attempts requiring inpatient medical treatment:

Statewide 8524

Bucks County 324

Chester County 243

Delaware County 347

Montgomery County 437

Philadelphia County 1014

This indicates that the five-county region accounts for almost 28% of medically serious

intentional self-injuries in Pennsylvania requiring hospital treatment.

According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), it is generally accepted

that there are at least 25 suicide attempts for every death by suicide. This can be used to derive

a rough approximation of the total suicide attempts in the state (47,175) and in the region

(13,050) in 2019.

[ 7 ]

SUICIDE ATTEMPTS ARE A HIGH PRIORITY COMMUNITY HEALTH PROBLEM

A suicide attempt may be thought of as the behavior that may immediately precede and

bring about a suicide fatality. It involves all of the elements of a suicide except death. These

include the intent to die, a plan for how, where, and when, and the means to be used to take

one’s life. A suicide attempt survivor is an individual who had intent to die, a plan for

bringing about her or his death at a specific time and place, and the means to do so, but for

some reason, did not die as intended, planned, and acted.

Of the components of a suicide attempt that did not end in death, intent to die is both the

most serious and transient. It may subside on its own or as the result of intervention or

treatment. A suicide plan once conceived and means once selected are more durable. Plans

remain available and may be revisited if intent returns. A suicide plan and means may also

become more lethal.

A suicide attempt that did not become a suicide is the strongest risk factor for a subsequent

attempt and suicide. The AFSP advises that between 25% and 50% people who kill

themselves had previously attempted suicide. Those who have made suicide attempts are

at higher risk for actually taking their own lives. While most who survive a suicide attempt

do not re-attempt, they remain at high risk, some very high. Of suicide attempt survivors who

required treatment in a hospital, about 5% to 11% go on to die by suicide.

The Interpersonal Psychological Theory (IPPT) of suicide is the prevalent theoretical model of

suicide and has been supported by research across various populations. It posits that a

potentially lethal suicide attempt may occur when an individual has both an intense desire to

die and the ability to take her or his life. Intent may arise from a sense that one is socially

disconnected from significant others or is a burden to them and that they will be better off if

one were dead. The capability for a suicide attempt is achieved when one does not fear dying

and has overcome the inborn resistance to self-directed death. This may come about in various

ways but perhaps the most effective is by making a suicide attempt. Resistance to dying by

one’s on hand weakens with each attempt.

A key tenet of the IPPT and related theories is that a suicide attempt is not primarily the

product of and impulsive decision. Impulsivity makes an attempt more likely but most often it is

the outcome of a process of psychosocial debilitation. The factors driving this process do not

necessarily abate with the attempt, even when the intent to die is lessened. One of the most

dangerous myths of suicide is the belief that surviving a suicide attempt indicates a lack of

intent to die. This misconception ignores the reality that intent may be rekindled by subsequent

life circumstances and/or misperceptions of one’s value to others, may rejoin the strengthened

acquired ability to die by suicide, and restart the downward process towards an attempt.

[ 8 ]

SELECTED RESEARCH FINDINGS ON SUICIDE ATTEMPT SURVIVORS

Key findings from recent studies of suicide attempt survivors’ postvention needs and

preferences, impediments to access to mental health services and recommended changes:

A first suicide attempt creates high risk for suicide; the great majority of completed

suicides occur within a year of the first attempt, hospitalization following the attempt,

as well as a scheduled follow-up visit with a psychiatrist significantly, reduced that risk.

Persons who made suicide attempts had disproportionately elevated risk because of

high levels of economic insecurity associated with unemployment and low income and

educational attainment.

Persons who have made a suicide attempt are may not disclose it to avoid stigma.

Responding to anticipated suicide stigma was found to be significantly associated with

increased suicidality in attempt survivors.

Persons who have made a suicide attempt want practical information countering

stigma, addressing negative community attitudes towards suicide, and promoting hope.

Personal stories of recovery by attempt survivors were identified as very useful.

Person who have made a suicide attempt and treated in a hospital emergency

department provide family information but collateral contacts may not be made and

when they are family members are not always given written information on resources.

Persons who made suicide attempts and participated in a Survivors of Suicide Attempts

peer-led support group for 8-weeks offering peer discussion and information sharing

had a decrease in suicidality and hopelessness and a significant increase in resilience.

Persons who made suicide attempts and who were treated in an emergency psychiatric

unit received follow-up telephone calls from a psychiatric nurse at 8, 30, and 60 days

within one year after discharge made fewer subsequent attempts.

Low social support was strongly associated with suicide attempts among low-income

African American men and women treated at a large, urban hospital. Greater availability

of social supports can be a protective factor for suicide attempts in this population.

Persons who made suicide attempts and who were associated with a suicide education

advocacy project reported a high degree of engagement with mental health services but

experienced stigma, loss of autonomy, issues with assessment and medication.

[ 9 ]

Persons who made suicide attempts and utilized available mental health services

reported dissatisfaction with outpatient and inpatient treatment. Most recommended

that being able to connect with persons with lived experience would be helpful.

Persons who made suicide attempts who are members of gender and sexual minorities

reported severe stigma and hopelessness after their attempts. They identified a need for

peer support to enhance their recovery and reduce the risk of future attempts.

Two-thirds of persons who made a recent suicide attempts surveyed as part of the

National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions had a diagnosis of

borderline personality disorder and experienced negative provider attitudes.

Persons who made suicide attempts in a South African study voiced a desire for mental

health services addressing suicide risk and deterring suicidal behavior, teaching self-help

strategies and promoting social connectiveness and support.

A study of psychiatric inpatients who had made suicide attempts found that those who

had made only one attempt reported less social support than those who had made

multiple attempts suggesting that support may be a buffer against further attempts.

Persons who made planned suicide attempts manifest distinct suicide-related clinical

characteristics that are severe and warrant early, targeted intervention and long-term

follow-up by treatment providers.

[ 10 ]

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY

The study was generally qualitative in nature and loosely involved a mixed methods approach

including the following activities:

Consultation with groups and organizations involved with suicide prevention, crisis

intervention, and mental health advocacy to determine interest in the topic. A one-page

outline of the proposed study was distributed by e-mail to prospective stakeholders in

the 5-county region.

Review of research articles reporting the need for support by suicide attempt survivors

or findings relevant to this topic.

Review of the literature describing support resources (e.g., peer support, peer-led

groups) for suicide attempt survivors

Identifying existing suicide attempt support resources in SE PA by surveying health and

behavioral health providers serving individuals who have made suicide attempts.

Consultation with a focus group of individuals with lived experience of a suicide attempt

or an interest in developing supports for suicide attempt survivors

Surveying individuals in SE PA who identified as suicide attempt survivors or who had

felt at risk of making a suicide attempt to determine the type of support resources they

feel best supports the needs of persons recovering from a suicide attempt. A copy of the

questionnaire is in the Appendices.

[ 11 ]

SUICIDE ATTEMPT SUPPORT NEEDS SURVEY

Summary:

Majority of respondents do not feel that mental health services do enough to help

suicidal persons

Majority of respondents feel there is a need for a suicide attempters support group

Majority of respondents would seek help from a peer specialists with lived experience of

a suicide attempt

Majority of respondents felt that should be a warm line for persons having thoughts of

suicide

Majority of respondents would seek help from a family member, other trusted person, a

peer specialist, or a peer-led resource if having thoughts of making a suicide attempt

All respondents feel that psychiatric hospitals should have inpatient suicide prevention

groups

Great majority of respondents acted in some way to make a suicide attempt

Almost three-fourths of respondents made two or more suicide attempts

Most respondents who made a suicide attempt sought medical help

Almost one-half of respondents who made attempt had thoughts of suicide in the past

and over one-third had frequent thoughts of suicide

1. Do mental health services offer enough help for suicidal persons?

Strongly Agree 2 5.35

Agree Somewhat 4 10.5%

Strongly Disagree 20 52.6%

Agree Somewhat 12 31.6%

2. Do you feel there is a need for a support group to help persons who have made suicide

attempts?

Yes 36 94.7%

No 0 -

DK 2 5.3%

3. Would you seek help from a peer specialist who had experienced a suicide attempt if one

were available?

Definitely Would 19 50.0%

Probably Would 10 26.3%

Probably Would Not 7 18.4%

Definitely Would Not 0 -

[ 12 ]

4. Do you think that there should be a 24/7 peer warm line for persons with thoughts of

suicide?

Yes 34 89.5%

No 1 2.6%

DK 3 7.9$

5. What would you do to get help if you had thoughts of making a suicide attempt?

Family Member, Friend, Other Trusted Person 10 26.3%

Peer Specialist or Other Peer-led Resource 9 23.7%

Use W.R.A.P. or Safety Plan 3 7.9%

Hot Line, Crisis Center, Mobile Crisis Team 8 21.0%

Hospital Emergency Department 6 15.8%

6. Should psychiatric hospitals have suicide prevention groups for current patients?

Strongly Agree 25 65.8%

Agree 13 34.2%

Strongly Disagree 0 -

Disagree 0 -

7. Have you ever made a suicide attempt, i.e., wanted to die and did something to try to end

your life?

Yes 33 86.8%

No 5 13.2%

8. If yes, how many suicide attempts have you made?

One 9 27.3%

Two to four 19 57.6%

Five or more 4 12.1%

9. If yes, did you ever require medical treatment for hurting yourself in a suicide attempt?

Received care at a hospital/healthcare provider 24 72.7%

Did not seek medical treatment 5 15.1%

Did not need medical treatment 4 12.1%

10. If yes, have you ever had thoughts of making a suicide attempt or making another attempt?

Have had thoughts in the past 16 48.5%

Have frequent thoughts 12 36.4%

Have not had any thoughts 5 15.1%

[ 13 ]

SUPPORT RESOURCES IN SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA

An internet search and inquiries to stakeholders did not identify any community-based support

groups or other resources in the region with the explicit mission or purpose of aiding or

supporting suicide attempt survivors. The following resources offering help to persons troubled

by suicidal thoughts and behaviors are presently available in the five-county area. At the time of

this writing, all groups are meeting online because of COVID-19.

Bucks County

Alternatives to Suicide Peer-to-Peer Support Group: Sponsored by NAMI Bucks County.

Meets 2

nd

and 4

th

Tuesdays and every Saturday. “The opportunity to talk openly about

suicide and feelings of deep emotional distress with others who have or are

experiencing similar struggles.”

Chester County

None located

Delaware County

None located

Montgomery County

Alternatives to Suicide Peer-to-Peer Support Group: Program of Resources for Human

Development initiated in March 2019, hosting weekly meetings in Abington, PA, where

individuals can discuss and explore suicidal thoughts and feelings.

Philadelphia County

None located

Regional

AFSP of Greater Philadelphia includes the page “I’ve survived a suicide attempt” on its

website at https://afsp.org/after-an-attempt offering information for suicide attempt

survivors.

[ 14 ]

THE NATIONAL SUICIDE PREVENTION LIFELINE AS A RESOURCE

MCES has been part of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline since 2014. We frequently

receive on the Lifeline are from individuals who feel at risk of making a suicide attempt. There

are now three other Lifeline call centers in SE PA. How can this availability and accessibility be

used to optimally serve suicide attempt survivors and others at risk of suicidal behavior? A 2007

publication, Lifeline Service and Outreach Strategies Suggested by Suicide Attempt Survivors,

offers several recommendations that are still timely:

Crisis line workers should recognize that attempt survivors who are struggling with

thoughts of suicide often feel immobilized. Just calling the hotline is a big step.

Therefore, working with a caller to develop a plan—including encouraging him/her to

call back and report on progress—will have helped the person substantially.

Follow-up calls for attempt survivors would be both welcome and beneficial. Primarily,

helping survivors set “achievable goals” and empowering them to facilitate their own

linkages to services would be most helpful. The crisis line worker could then follow-up

with the caller to see how the call went.

The Lifeline should offer resources dealing with the issue of isolation and opportunities

for callers to become involved in groups or organizations in their communities.

Some “suicide prevention lines” only serve persons who are suicidal. Suicide prevention

lines, such as the Lifeline, should serve not only imminently suicidal persons but also

persons in emotional distress, to help them before they are in danger.

The Lifeline should engage peers (i.e., attempt survivors) to be “mentors” for persons

who have recently attempted suicide, providing understanding, support, and hope.

When people call, they need is warmth and compassion, not someone who is going to

take information quickly and then move to an intervention as quickly as possible. If a

survivor believes the person answering the call is taking a clinical position, they will

likely hang up, stop talking, or not tell the truth about what is going on.

Crisis line workers should be direct, talk about suicide, and not hide it under other things

such as depression.

Full or part-time crisis workers primarily trained and experienced in mental health crisis

intervention staff three of the four Lifeline centers in SE PA, including MCES. Some of these

recommendations suggest that suicide attempt postvention should be added to their skill set.

[15]

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. The county suicide prevention task forces in region or other appropriate stakeholder

should facilitate the formation of a suicide attempters support group in their respective

counties.

2. The county suicide prevention task forces in Chester, Delaware, and Philadelphia

Counties or other appropriate stakeholder should facilitate the formation of an

Alternatives to Suicide Peer-to-Peer Support Group in their respective county.

3. Freestanding psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric units at community hospitals in the

region should initiate voluntary inpatient suicide prevention groups for their inpatients.

4. Freestanding psychiatric hospitals should include information for patients and family

members on dealing with thoughts of suicide and resources for suicide attempt

survivors in the discharge packets required by The Joint Commission.

5. Certified Peer Specialists in the region should receive training to enable them to provide

peer counseling to persons seeking their help with thoughts of suicide or other suicidal

behavior.

6. The county suicide prevention task forces in region or other appropriate stakeholder

should facilitate the expansion of peer-led warm lines to offer support 24/7 to persons

having thoughts of suicide.

7. Create a State Suicide Attempt Survivor web site in Pennsylvania.

Here are examples from other states:

Suicide Prevention: attempt survivors | Mass.gov https://www.mass.gov/info-

details/suicide-prevention-attempt-survivors

FL Department of Children and Families https://www.myflfamilies.com/service-

programs/samh/prevention/suicide-prevention/suicide-attempt-survivors.shtml

Attempt Survivors : Lifeline (suicidepreventionlifeline.org)

https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/help-yourself/attempt-survivors/

Survivors of Suicide Attempt — South Dakota Suicide Prevention

(sdsuicideprevention.org) https://sdsuicideprevention.org/survivors/survivors-of-

suicide-attempt/

[16]

SELECTED RESOURCES FOR ATTEMPT SURVIVORS

This listing is not exhaustive and is for information only. Inclusion does not imply endorsement.

Support Groups Development

Manual for Support Groups for Suicide Attempt Survivors. Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services,

https://didihirsch.org/wp-

content/uploads/Manual_for_Support_Groups_for_Suicide_Attempt_Survivors.pdf

Support Group Facilitation Guide. Mental Health America.

https://www.mhanational.org/sites/default/files/MHA%20Support%20Group%20Facilitation%2

0Guide%202016.pdf

Self-help Guides

“A Guide for Taking Care of Yourself after your Treatment in the Emergency Department.”

SAMHSA. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/A-Guide-for-Taking-Care-of-Yourself-After-Your-

Treatment-in-the-Emergency-Department/SMA18-4355ENG

A Journey Toward Health and Hope: Your Handbook for Recovery After a Suicide Attempt.

SAMHSA. https://suicidology.org/wp-

content/uploads/2019/06/HandbookForRecoveryAfterAttemptSAMHSA.pdf

"Now Matters Now" Ursala Whiteside. Teaches specific emotion regulation skills.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JV81fmuvqoI&list=UU_NQ14VoXhmabaSZ4RWgKWw

Toolkit for People who have been Impacted by a Suicide Attempt. Mental Health Commission of

Canada, Ottawa, ON. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/2018-

05/suicide_attempt_toolkit_eng.pdf

Web Sites

“After an Attempt” AFSP. https://afsp.org/after-an-attempt

“After a Suicide Attempt” Beyond Blue. https://www.beyondblue.org.au/the-facts/suicide-

prevention/after-a-suicide-attempt

“Live Through This” Resource supporting and advocating for persons who have made a suicide

attempt and educating others about suicide. https://livethroughthis.org

“With Help Comes Hope: Support for Persons Living with Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide

Attempts.” https://lifelineforattemptsurvivors.org/for-friends-family/7-things-attempt-

survivors-wish-their-families-and-friends-knew/

[ 17 ]

Connections. https://livedexp.academy/ Directory those who have survived attempts can use to

connect with others who have “been there” for support.

“Lived Experience Academy” https://livedexp.academy Educational website to help suicide

attempt survivors after they have gotten through a suicidal crisis,

“A Voice at the Table” http://avoiceatthetable.org/index.html “The national ‘home base’ for

the Family & Friends emotionally impacted by the suicidal crisis of a loved one.”

“Suicide is Different” https://www.suicideisdifferent.org/ A site for “suicide caregivers” who are

“struggling with someone with thoughts of suicide.”

[ 18 ]

SOURCES

The following publications were reviewed in the course of this study. Findings pertinent to the

focus of this study are summarized above.

Bantjes J. 'Don't push me aside, Doctor': Suicide attempters talk about their support

needs, service delivery and suicide prevention in South Africa. Health Psychology Open.

2017 Sep 8;4(2):2055102917726202..

Berardelli I, Forte A, Innamorati M, Imbastaro B, Montalbani M. et al. Clinical Differences

Between Single and Multiple Suicide Attempters, Suicide Ideators, and Non-suicidal

Inpatients. Frontiers of Psychiatry. 2020 Dec 15;11:605140. doi:

10.3389/fpsyt.2020.605140. PMID: 33384631; PMCID: PMC7769945.

Bostwick, J, Pabbati, C, Geske, M, McKean, A. Suicide Attempts as a Risk Factor for

Completed Suicide: Even More Lethal than we Knew. American Journal of Psychiatry 2016

173:11; 1094-1100

Chaudhury, S. Singh, T., Burke, A., Stanley, B., Mann, J, Grunebaum, M., Sublette, M.

Oquendo, M. (2016). Clinical Correlates of Planned and Unplanned Suicide Attempts.

Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204(11), 806–811.

Karen Chesley, Nancy E Loring-McNulty, Process of suicide: perspective of the suicide

attempter, Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 9: 2, 2003, 41-45,

Compton M, Thompson N, Kaslow N. Social environment factors associated with suicide

attempt among low-income African Americans: the protective role of family

relationships and social support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatr Epidemiology. 2005

Mar;40(3):175-85.

Exbrayat S, Coudrot C, Gourdon X, Gay A, Sevos J, Pellet J, Trombert-Paviot B, Massoubre

C. Effect of telephone follow-up on repeated suicide attempt in patients discharged from

an emergency psychiatry department: a controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017 Mar

20;17(1):96.

Hom, M. A., Albury, E. A., Gomez, M. M., Christensen, K., Stanley, I.et al.. (2020). Suicide

attempt survivors’ experiences with mental health care services: A mixed methods

study. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51(2), 172–183.

[ 19 ]

Hom, M., Bauer, B, Stanley, I, Boffa, J, Stage, D, et al. (2020). Suicide attempt survivors’

recommendations for improving mental health treatment for attempt

survivors. Psychological Services. Advance online

publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000415

Hom, M, Davis, L., & Joiner, T. (2018). Survivors of Suicide Attempts (SOSA) support

group: Preliminary findings from an open-label trial. Psychological Services, 15(3), 289-

297.

García de la Garza Á, Blanco C, Olfson M, Wall MM. Identification of Suicide Attempt

Risk Factors in a National US Survey Using Machine Learning. JAMA

Psychiatry. Published online January 06, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4165

Oexle, N., Herrmann, K., Staiger, T., Sheehan, L., Rüsch, N., & Krumm, S. (2019). Stigma

and suicidality among suicide attempt survivors: A qualitative study. Death Studies,

43(6), 381–388.

Mayer, L., Rüsch, N., Frey, L., Nadorff, M., Drapeau, C, Sheehan, L. and Oexle, N. (2020),

Anticipated Suicide Stigma, Secrecy, and Suicidality among Suicide Attempt Survivors.

Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 50:706-713.

McGill K, Hackney S, Skehan J. Information needs of people after a suicide attempt: A

thematic analysis. Patient Education and Counseling. 2019 Jun;102(6):1119-1124. doi:

10.1016/j.pec.2019.01.003. Epub 2019 Jan 8. PMID: 30679002.

Olfson M, Blanco C, Wall M, Liu SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Grant BF. National Trends in

Suicide Attempts among Adults in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Nov

1;74(11):1095-1103. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2582. PMID: 28903161; PMCID:

PMC5710225.

Jessica Rassy, Diane Daneau, Caroline Larue, Elham Rahme, Nancy Low et al.

(2020) Measuring Quality of Care Received by Suicide Attempters in the Emergency

Department, Archives of Suicide Research, DOI: 10.1080/13811118.2020.1793043

Stellrecht, N, Gordon, K, Van Orden, K, et al. Clinical applications of the interpersonal-

psychological theory of attempted and completed suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychology

2006;62:211-222.

Taylor M. Binnix, Carol Rambo, Seth Abrutyn, Anna S. Mueller (2017): The

Dialectics of Stigma, Silence, and Misunderstanding in Suicidality Survival Narratives,

Deviant Behavior, DOI: 10.1080/01639625.2017.1399753

[20 ]

Robert J. Valuck, Anne M. Libby, Tami D. Benton, Dwight L. Evans, A Descriptive Analysis

of 10,000 Suicide Attempters in United States Managed Care Plans,1998–2005. Primary

Psychiatry. 2007;14(11):52-60

Stanley I, Boffa J, Joiner, T. PTSD From a Suicide Attempt: Phenomenological and

Diagnostic Considerations. Psychiatry. 2019 Spring; 82(1):57-71. doi:

10.1080/00332747.2018.1485373. Epub 2018 Sep 5. PMID: 30183554; PMCID:

PMC6401333.

Williams, S, Frey, L., Stage, D, Cerel, J. (2018). Exploring lived experience in gender and

sexual minority suicide attempt survivors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(6),

691–700.

[ 21 ]