International Monetary Fund | April 2023 45

The natural rate of interest—the real interest rate

that neither stimulates nor contracts the economy—is

important for both monetary and fiscal policy; it is a

reference level to gauge the stance of monetary policy

and a key determinant of the sustainability of public

debt. This chapter aims to study the evolution of the

natural rate of interest across several large advanced and

emerging market economies. To mitigate the uncertainty

that typically surrounds estimates of the natural rate, the

chapter relies on complementary approaches to analyze

its drivers and project its future path. Common trends

such as demographic changes and productivity slowdown

have been key factors in the synchronized decline of the

natural rate. And while international spillovers have been

important determinants of the natural rate, offsetting

forces have resulted in only a moderate impact on balance.

Overall, the analysis suggests that once the current

inflationary episode has passed, interest rates are likely to

revert toward pre-pandemic levels in advanced economies.

How close interest rates get to those levels will depend on

whether alternative scenarios involving persistently higher

government debt and deficit or financial fragmentation

materialize. In major emerging market economies, natural

interest rates are expected to gradually converge from

above toward advanced economies’ levels. In some cases,

this may ease the pressure on fiscal authorities over the

long term, but fiscal adjustments will still be needed in

many countries to stabilize or reduce debt-to-GDP ratios.

Introduction

In 1979, the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates

from about 10 percent at the start of the year to

almost 14 percent by the year’s end, which in real

terms—after taking account of inflation—amounted to

a rate of interest of about 5 percent.

1

Even at the time

e authors of this chapter are Philip Barrett (co-lead), Christoffer

Koch, Jean-Marc Natal (co-lead), Diaa Noureldin, and Josef Platzer,

with support from Yaniv Cohen and Cynthia Nyakeri. e authors

thank John Williams for very helpful comments.

1

When comparing interest rates, it is important to take account

of inflation. Savings invested at 5 percent when inflation is 2 percent

will buy the same thing as an investment at 3 percent when infla-

tion is zero.

this was viewed as likely insufficient to tame rapidly

rising inflation.

2

And so it proved to be. Inflation

continued to rise, peaking at nearly 15 percent the

following year, requiring even higher interest rates and

a prolonged recession before the situation was brought

under control.

Nearly three decades later as the world faced the

global financial crisis of 2008, the Federal Reserve—

along with central banks worldwide—slashed interest

rates to as close to zero as they thought possible in

nominal and real terms. is time around, however,

commentators and policymakers raised concerns that

interest rates were not low enough to boost demand

and inflation. Once again, these concerns proved

well-founded, with inflation remaining stubbornly low

for much of the next 10 years.

ese two contrasting examples raise an obvious

question. How can it be that in the same country a

real interest rate of 5 percent is sometimes too low but

at other times a real interest rate of zero is too high?

Most answers rely on the idea that a given real

interest rate does not have the same macroeconomic

effects at all times. Instead, the impact is relative to

some reference level. When real interest rates are below

that level, they are stimulatory, boosting demand and

inflation. And when above it, they are contractionary,

lowering output and inflation. If this reference level

moves over time, then the same real interest rate can

be too high or too low at different times.

Macroeconomists call this reference interest rate

the “real natural rate of interest.”

3

e “natural” part

means that this is the real interest rate that is neither

stimulatory nor contractionary and is consistent with

output at potential and stable inflation. Lowering the

real rate below the natural rate is akin to stepping on

the macroeconomic accelerator; raising it above is like

hitting the brake. e natural rate is usually thought of

as independent of monetary policy and instead driven

2

See Goodfriend and King (2005).

3

In many discussions, the “real” part is dropped; this approach is

followed in the chapter. Some economists use the terms “neutral”

and “natural” interchangeably, and some do not. For clarity, this

chapter uses only “natural.”

THE NATURAL RATE OF INTEREST: DRIVERS AND

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

2

CHAPTER

46 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

by real phenomena such as, for instance, technological

progress, demographics, inequality, or preference shifts

for safe and liquid assets.

4

As the preceding discussion suggests, the natural

rate is important for the conduct of monetary policy.

Policymakers need to know the level of the natural

rate in order to gauge the likely impact of their poli-

cies and so assess the stance of monetary policy. e

natural rate also has a critical influence on fiscal pol-

icy. On average over the long term, monetary policy is

typically neither inflationary nor contractionary. And

so the natural rate is also an anchor for real rates over

long periods of time. Because governments typically

pay back debts over long time spans (both through

long-maturity debt and by rolling over short-term

debt), the natural rate is essential in determining the

overall cost of borrowing and the sustainability of

public debts.

Given the importance of the natural rate for both

monetary and fiscal policy, it is not surprising that

the recent surge in inflation and government debt

worldwide has led to renewed interest in this topic.

Real rates have increased a bit as monetary policy has

become tighter in response to higher inflation. But

the uptick remains modest compared with the late

1970s. Whether central banks have raised rates enough

to return inflation to target depends critically on the

level of the natural rate. Similarly, the natural rate will

determine how much of a burden the present-day high

levels of debt will be for governments (see Chapter 3).

In light of these concerns, the chapter seeks to

answer the following questions:

• How has the natural rate evolved in the past across

different economies?

• What has driven this evolution?

• What is the outlook for these drivers and natural

rates in the near and medium term?

• How will this outlook affect monetary and

fiscal policies?

To shed light on these issues, the chapter first reviews

the main stylized facts that characterize real interest

rate trends at different maturities and across different

countries. It then sets out to measure the natural rate.

To mitigate the unavoidable uncertainty associated with

estimations of the natural rate, the chapter will follow

4

In line with a long tradition in monetary economics, monetary

policy is here assumed to be neutral, meaning that it does not affect real

variables over the long term. Borio, Disyatat, and Rungcharoenkitkul

(2019) present an alternative view and implications for the natural rate.

a two-pronged approach. Beginning with a simple

model (Laubach and Williams 2003)—one that lets the

data speak—it moves to a tighter theoretical structure

that imposes more restrictions on the data but allows a

deeper understanding of the underlying drivers of the

natural rate (Platzer and Peruffo 2022). Comparing

estimates from different models provides independent

validation. In addition, alternative scenarios covering

a range of plausible future developments for the main

underlying drivers of the natural rate are considered

for robustness. ese projections provide a long-term

anchor for monetary policy and a crucial input to

analyze debt sustainability in the largest advanced and

emerging market economies.

e main findings of the chapter are as follows:

• Common trends have played an important role in

driving real interest rates down. The natural rate

has declined over the past four decades in most

advanced economies and some emerging markets.

While idiosyncratic factors can explain cross-country

differences, common trends underlying demographic

transitions and productivity slowdowns are key to

understanding the synchronized decline.

• Global drivers have also been important determinants

but on balance have had a limited impact on net cap-

ital flows and corresponding natural rates in advanced

and emerging market economies. As global capital

markets opened and fast-growing emerging market

economies entered the scene in the 1980s and

1990s, foreign factors increasingly shaped long-term

trends in interest rates. High growth in emerging

markets has tended to drive up interest rates in

advanced economies while producing a glut of

savings in emerging markets. These excess savings—

in their quest for safe and liquid assets—have tended

to flow back to advanced economies, pushing

natural interest rates back down. On balance, these

forces seem to have had broadly offsetting effects on

capital flows and a moderate impact on natural rates

over the past half-century.

• Country-specific natural rates of interest are projected

to converge in the next couple of decades. Based on

conservative assumptions on demographic, fiscal,

and productivity developments, it is anticipated that

natural rates in large emerging market economies

will decline, gradually converging toward the low

and steady levels expected in advanced economies.

• As inflation returns to target, the effective lower

bound on interest rates may become binding again.

Post-pandemic increases in interest rates could be

47International Monetary Fund | April 2023

CHAPTER 2

THE NATURAL RATE OF INTEREST: DRIVERS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

protracted until inflation is brought back to target

(Chapter 1). However, long-term forces driving

the natural rate suggest that interest will eventually

converge toward pre-pandemic levels in advanced

economies. How close to those levels will depend on

whether alternative scenarios involving persistently

higher government debt and deficit or financial

fragmentation materialize. Because nominal rates

cannot fall far below zero (the effective lower bound

constraint), this could limit central banks’ ability to

respond to negative demand shocks. Thus, debates

about the appropriate level of target inflation at

the effective lower bound could reemerge. Even the

central banks in some emerging market economies

may eventually need to adopt unconventional policy

tools similar to those used by advanced economies

in recent years.

• Despite increased fiscal space, many countries will

have to consolidate. While low natural rates may

ease pressure on fiscal policy, they do not negate

the need for fiscal responsibility. Important gov-

ernment support during the pandemic has strained

public accounts, requiring some budget consol-

idation to ensure long-term debt sustainability.

Various paths to deficit reduction are open, but

delaying action will only make the required steps

more drastic: Larger public debt tends to crowd

out private investment and erode the appeal of safe

and liquid government debt.

Trends in Real Rates over the Long Term

is section lays out some basic facts about how real

interest rates have evolved over the long term. Because

the natural rate is an anchor for real interest rates,

long-term trends in real interest rates are potentially

informative signals about the natural rate itself.

Figure 2.1, panel 1, starts the inquiry by comparing

five different measures of the ex ante real interest rate

for the United States.

5

Different maturities from 1 year

up to 20 years are considered. Despite differences at

high frequencies—the short-horizon measures are

5

Ex ante measures of the real interest rate use actual measures of

inflation expectations, which are either extracted from financial mar-

kets or based on surveys, to deflate the nominal interest rate. Ex post

real interest rates rely instead on realized inflation. Over long periods

of time, ex ante and ex post real interest rates tend to coincide, but

there can be large discrepancies when surprise inflation is expected to

be temporary, as in the most recent episode. Unfortunately, inflation

expectation measures are not always available for long time series,

emerging markets, or both.

unsurprisingly much more volatile—all these measures

share a common long-term trend. Looking through

cyclical fluctuations and term premiums, real rates

have fallen steadily, by about 5 percentage points over

the last four decades across all maturities. Given that

the natural rate of interest is a long-term attractor for

real rates, this suggests that the natural rate of interest

has also fallen, at least in the United States.

To get a sense of whether these developments have

been mirrored elsewhere, Figure 2.1, panel 2, compares

historical ex post real rates in five advanced economies

over a similar period, in this case using three-month

real rates. e broad pattern is the same, with real

rates declining steadily from highs in the 1980s.

Interestingly, the common international component

seems at first glance to have become more important

over time, with countries’ real rates seeming to con-

verge gradually.

1-year 2-year 5-year

10-year 20-year

United States Japan Germany

United Kingdom France

Figure 2.1. Real Interest Rate Trends

(Percent)

1. (Ex Ante) Real Interest Rates at Different Maturities in

the United States

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

8

10

1982 90 2000 10 20 Feb.

23

2. (Ex Post) Real Short-Term Interest Rates in Selected

Advanced Economies

1982 90 2000 10 20 Nov.

22

–10

–5

0

5

10

15

20

Sources: Federal Reserve Economic Data; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: In panel 1, the real interest rates are computed as the difference between

the US Treasury rate at each horizon and the Cleveland Federal Reserve measure

of inflation expectations over the same horizon. In panel 2, the real interest rates

are the difference between the three-month interbank rates and the average of the

realized inflation measured by the consumer price index in the next three months

for each country. Japan’s three-month interbank rates are spliced with rates for

certificates of deposit from 1979 to 2002. Online Annex 2.1 provides details on

data sources and calculations for the figure.

48 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

Figure 2.2 contrasts developments in advanced and

emerging market economies. A shared trend at the

start of the 2000s decoupled later on as real rates con-

tinued to decline in advanced economies but stabilized

at their 2005 level in emerging markets.

Overall, this first look at the data suggests that

the natural rate has likely declined in the past four

decades or so in advanced economies. is downward

trend seems to be increasingly common across coun-

tries and points to some global drivers. e picture

is different in emerging markets, where natural rates

have remained broadly stable over the past 20 years

on average. Because emerging market and advanced

economies’ current accounts are broadly balanced,

the divergence in long-term rates points to remaining

frictions preventing a stronger convergence between

advanced and emerging market economies (Obstfeld

2021).

6

Yet this analysis leaves many important issues

unaddressed. e data, although suggesting that the

natural rate has declined in many advanced economies,

6

Beyond market frictions, weak institutions and lack of investor

protection in recipient countries may also explain the lack of

convergence. An alternative explanation, which is likely to be

particularly relevant for the United States, is that following the

global financial crisis, emerging market debt was not considered

safe, pushing down the real interest rate for the main provider of

safe and liquid assets.

cannot explain why this decline occurred and fail to

distinguish the impact of secular and cyclical factors.

e following sections tackle these concerns.

Measuring the Natural Rate

is section relies on well-known macroeconomic

empirical models to try to estimate the natural rate

of interest. Because the natural rate is an unobserved,

latent variable, any measurement requires some theory.

e approach here is to use a minimal amount of

theory, drawing on simple macroeconomic relation-

ships between aggregate supply and demand, interest

rates, and inflation. Approaches based on aggregate

relationships are a good starting point for developing

a more informed measure of the natural rate because

they are transparent and straightforward. Subsequent

sections use a richer framework based on more exten-

sive microeconomic theory and so speak more to the

underlying drivers of the natural rate.

Single-Country Estimates of the Natural Rate

e first approach is an application of the widely

used Laubach-Williams model (Holston, Laubach, and

Williams 2017; hereafter HLW). is model assumes

a set of relationships between supply, demand, interest

rates, and prices consistent with perhaps the most

standard macroeconomic view of the world, the New

Keynesian model.

7

In this setting, the natural rate is

driven by a variety of shocks, including trend output

growth. Here, it is defined as the real interest rate that

will return output to potential and inflation to target,

once purely transitory shocks to aggregate supply or

demand have dissipated. e intuition for this is that

central banks tend to think about returning inflation

to target in the medium term, because trying to offset

every temporary shock would lead to undue volatility

in interest rates and output.

8

7

See Online Annex 2.2 for a formal description of the model. All

online annexes are available at www .imf .org/ en/ Publications/ WEO.

8

In this framework, financial shocks affect the natural rate only if

they affect potential output. A persistent increase in precautionary

saving or preference for safe and liquid assets would qualify, whereas

purely transitory variation in risk aversion, for example, would not

(Barsky, Justiniano, and Melosi 2014; Gourinchas, Rey, and Sauzet

2022). is definition of the natural rate is consistent with the one

implicit in the theoretical framework of the next section, because it

emphasizes low-frequency movements of the real interest rate in a

world without nominal friction (where output is at potential).

Advanced economies

Emerging market and developing economies

Figure 2.2. (Ex Post) Real Interest Rates in Advanced and

Emerging Market and Developing Economies

(Percent)

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

2003 06 09 12 15 18 22

Divergence after 2011

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: The sample comprises 34 advanced economies and 25 emerging market

and developing economies, aggregated using market-exchange-rate-based GDP

weights. Maturity of the bonds is greater than one year. Nominal interest rates are

deflated using consumer price inflation.

49International Monetary Fund | April 2023

CHAPTER 2

THE NATURAL RATE OF INTEREST: DRIVERS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

e model is first estimated from data for one

country at a time. As part of the estimation, the model

attempts to figure out what were the most likely

values for several key unobserved variables, including

potential output and the natural rate of interest, given

the (relatively standard) New Keynesian view of the

macroeconomy. is framework also offers a basic

decomposition of changes in the natural rate into two

components: one due to changes in the long-term

growth trend, and one due to other factors, which

can in principle include domestic and foreign drivers.

One drawback, however, is that the HLW model is

designed to apply principally to advanced economies,

for which data can be reasonably described by the

New Keynesian model over a long enough time period.

e richer structural model in the next section has

more to say about emerging markets.

Figure 2.3 summarizes the results from estimating

the HLW model on a sample of six advanced econo-

mies for which sufficient quarterly data exist. It shows

estimates of the natural rate, as well as the part due to

trend growth, for two five-year periods: one covering

the end of the 1970s, the other for the late 2010s.

ese estimates broadly confirm the intuition pre-

sented so far in this chapter: that the natural rate of

interest has declined across advanced economies in the

past 40 years. Despite some variation in the level of the

rate across countries, the magnitude of the decline has

been broadly similar, at a little over 2 percentage points

in most countries. is is much smaller than the over-

all decline in real interest rates over the same period (of

about 5 percentage points), which likely also reflected

the change in the monetary policy stance, particularly

tight at the beginning of the 1980s as central banks

fought historically high inflation.

However, the uncertainty over the estimates of the

natural rate is very large, with the 90 percent confi-

dence interval for the United States ranging from zero

to about 3 percent in the second half of the 2010s.

Uncertainty is a common feature of all estimates of

the natural rate

9

and arises because the estimated

relationships between interest rates and the output gap,

and the output gap and inflation, are both relatively

weak. As a result, fluctuations in output and inflation

provide little information about the overall level of the

natural rate. Yet at least one part of the natural rate

is well estimated: the trend growth component, for

9

See Arena and others (2020) for a related exercise applied to

European countries.

which confidence intervals are much smaller. is is

because data for output are directly informative about

trend growth.

One interesting feature of these results is that the

decline in the natural rate is so similar across advanced

economies despite such differing trend growth compo-

nents. With the exception of Japan, the natural rate

dropped more than implied by the change in growth

rates over the same period. is suggests that some

forces other than domestic growth may be inducing

Natural rate Growth component

1. Canada

2. France

1975–79 2015–19

1975–79 2015–19

3. Germany

4. Japan

1975–79 2015–19 1975–79 2015–19

5. United Kingdom

6. United States

1975–79 2015–19 1975–79 2015–19

Sources: Holston, Laubach, and Williams (2017); and IMF staff calculations.

Note: The ranges show 90 percent confidence intervals.

Figure 2.3. Kalman Filter Estimates of the Natural Rate of

Interest for Selected Advanced Economies

(Percent)

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

50 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

common movements in the natural rate. at esti-

mated natural rates are more similar across countries

now than 40 years ago is perhaps consistent with the

idea that capital market integration has progressed,

at least among advanced economies. is possibility

motivates an extended version of this model, which

allows for explicit international spillovers through

either real or financial channels (and is explored in the

section “Multicountry Estimates of the Natural Rate”).

The Natural Rate during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Despite its limitation, the closed economy model is

a useful benchmark for addressing two questions that

have gained attention during the post-pandemic infla-

tionary episode in many advanced economies. at

is: How much did policymakers stimulate during the

pandemic? And how fast did they tighten afterward?

One concern when answering these questions is

that any conclusions may unduly rely on the ben-

efit of hindsight. What now might appear to be

policy mistakes may have been perfectly reasonable

decisions for policymakers without the benefit of

perfect foresight.

To illustrate the challenges, Figure 2.4 shows

different vintages of measures of the real and natural

rates. e gap between the two is a summary measure

of whether monetary policy is tight (when the realized

real rate is higher than the natural rate; the gap is posi-

tive) or loose (when the gap is negative). e measures

differ in the data they use. e full-sample estimate (in

red) uses data up to the third quarter of 2022 and so

approximates the current best guess of what the natural

rate was at each point in time. is helps provide an

assessment of the monetary policy stance with the

benefit of hindsight. In contrast, contemporaneous

estimates (in blue) are computed by repeatedly running

the model, extending the data sample by one quarter

each time. is aims to approximate how the real rate

gap might have been assessed at the time.

Early in the pandemic, the two measures differed,

often considerably and usually with the contempo-

raneous estimate presenting a much tighter view of

monetary policy. is is consistent with the idea that

the shocks seen when the pandemic hit were highly

unusual, with both supply and demand moving far

and fast. Faced with contemporaneous data, this model

viewed supply shocks as having a large permanent

component, generating an exceptionally low natu-

ral rate and thus a tight stance for monetary policy.

Subsequent data helped correct this misperception,

with the sharp change in the natural rate early in the

pandemic progressively revised away. A reasonable

interpretation is that policymakers looked through the

immediate crisis, applied their judgment in a way that

Contemporaneous estimate

Estimates based on data up to 2022:Q3

Realized real interest rate

Figure 2.4. Real Rates and Natural Rates: Contemporaneous

and Current Estimates for Selected Advanced Economies

(Percent)

1. Canada

–10

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

Jan.

2019

Jan.

20

Jan.

21

Oct.

21

2. France

–10

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

Jan.

2019

Jan.

20

Jan.

21

Oct.

21

3. Germany

–10

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

Jan.

2019

Jan.

20

Jan.

21

Oct.

21

4. Japan

–10

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

Jan.

2019

Jan.

20

Jan.

21

Oct.

21

5. United Kingdom

–10

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

Jan.

2019

Jan.

20

Jan.

21

Oct.

21

6. United States

–10

–8

–6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

Jan.

2019

Jan.

20

Ja

n.

21

Oct.

21

Sources: Holston, Laubach, and Williams (2017); and IMF staff calculations.

Note: The ranges show 90 percent confidence intervals. Parameters are estimated

on pre-COVID data. The diamonds represent contemporaneous estimates at

2021:Q4 and realized real interest rates at 2022:Q4 for each country.

51International Monetary Fund | April 2023

CHAPTER 2

THE NATURAL RATE OF INTEREST: DRIVERS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

a model cannot, and so delivered moderately stimula-

tory policy.

10

Later in the pandemic, however, policy became

looser. And although the natural rate did rise a little in

most places, looser policy largely came about through

inflation eroding real policy rates. In contrast to the

early pandemic period, the red and blue dots are

generally very close. is says that subsequent data do

not tell us much that was not known at the time. And

so, while policymakers may have had good reasons not

considered here for conservatism in adjusting rates,

the HLW model suggests that policy was loose for a

long time in some countries (October 2022 Global

Financial Stability Report).

Multicountry Estimates of the Natural Rate

One drawback of the HLW approach is that it

involves a closed-economy model; it can only estimate

the natural rate for one country at a time. is is not

an issue when the goal is only to estimate the level of

the natural rate in a particular country. However, the

approach cannot be used for counterfactual analysis that

would try to assess something like the impact of a decline

in foreign potential growth on the domestic natural rate.

One way to address this is to use an explicitly inter-

national model. Wynne and Zhang (2018) proposed

one such framework that allows for two-way interac-

tions between two independent regions using an empir-

ical approach very similar to HLW. e framework

features an important general equilibrium aspect of the

determination of the natural rate via international spill-

overs. is is in line with international macroeconomic

theory that stipulates that when capital is internation-

ally mobile, the determination of natural rates entails

a global dimension (Clarida, Galí, and Gertler 2002;

Galí and Monacelli 2005; Metzler 1951; Obstfeld

2020). is also implies that if there are spillovers from

one country to another, then it stands to reason that

those effects might spill back over to the originator.

Specifically, the natural rate is now allowed to be

affected not just by domestic growth but also by

foreign growth. e intuition is that if foreign growth

increases, so do foreign rates of return, necessitating

greater compensation for domestic investors and driv-

ing up the domestic natural rate. Of course, changes

in the domestic natural rate affect domestic growth,

10

See Holston, Laubach, and Williams (2020) for a discussion on

how to adapt the HLW model to capture the pandemic.

which then spills back to the foreign natural rate

through a similar channel.

Figure 2.5 presents the results from such a model,

with the United States and the rest of the world as

the two regions.

11

As before, this setting suggests that

the natural rate in the United States has declined

by about 2 percentage points in the past 50 years or

so. In contrast, the estimated natural rate in the rest

of the world has been more stable, at least since the

mid-1970s. Two factors are responsible. First, as might

be expected, domestic growth rather than foreign

growth is more important for each (relatively closed)

region. Second, secular slowdown in many advanced

11

It is important to exercise caution when interpreting the quanti-

tative implications of this analysis. e estimation is not disciplined

by current account data, and so the decomposition may lump var-

ious effects together. Moreover, large confidence bands suggest that

inference is highly imprecise.

Natural rate United States growth

Rest of the world growth

Other factors

Figure 2.5. Measuring the Natural Rate: The Role of

International Spillovers

(Percent)

1. United States

–3

–2

–1

0

1

2

3

4

5

1970

80

90 2000 10 19

2. Rest of the World

–3

–2

–1

0

1

2

3

4

5

1970 80 90 2000 10 19

Sources: Wynne and Zhang (2018); and IMF staff calculations.

Note: “Rest of the world” comprises Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada,

China, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, India, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, The

Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland,

and the United Kingdom.

52 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

economies is offset by the rise of high-growth emerg-

ing market and developing economies, such as China,

propping up growth in the rest of the world. ese

elements working together have led to a higher and

more stable natural rate outside the United States.

Nevertheless, international spillovers are significant

and important for determining the level of the natural

rate. e analysis suggests two offsetting channels. e

first operates through overseas growth (in red), which

has helped support the natural rate in the United

States. e other channel is shown by the increasing

and negative impact of “other factors” (in yellow).

at this has had a long-lasting and negative effect

on the natural rate in the United States is consistent

with the idea that increased foreign demand for safe

and liquid US assets has depressed returns (Bernanke

2005; Caballero, Farhi, and Gourinchas 2008, 2016,

2017b; Pescatori and Turunen 2015), especially since

the global financial crisis. Note that the converse effect

in the rest of the world is smaller, which reflects the

relative sizes of the two regions.

Overall, this analysis suggests that foreign devel-

opments likely have had two offsetting effects on

natural rates in the United States. Sustained growth in

emerging markets has driven up the US interest rate

while simultaneously producing a glut of savings that

pulled it down again as foreign investors increasingly

demanded safe and liquid US government debt.

While more general than a closed economy model,

this framework still has an important drawback. It has

little to say about the true drivers of the changes in

the natural rate: What causes growth, either foreign

or domestic? What is behind “other factors”? e next

section tackles some of these questions.

Drivers of the Natural Rate

e aggregate macroeconomic models of the pre-

ceding sections can offer a very simple explanation for

why the natural rate has declined: While other factors

do play a role, growth—both foreign and domestic—

seems to be the most important factor. But this is

not very satisfying. “Growth” is a result of different

macroeconomic forces, not a primary force itself. For

example, while both demographic forces and pro-

ductivity growth could be responsible for the secular

decline in growth, each could have potentially very

different implications for the natural rate. Moreover,

these deeper forces may have offsetting effects not fully

captured by this simple decomposition.

Some Theory

Many possible economic mechanisms have been pro-

posed to explain variations in the natural interest rate.

eir importance can vary at different frequencies, with

“macroeconomic” forces more likely to drive long-term

trends and “financial” forces more likely to be import-

ant in the short to medium term, reflecting risk aver-

sion and leveraging cycles.

12

Of course, this distinction

is somewhat artificial because financial forces may drive

secular shifts in behavior that determines saving rates.

13

Macroeconomic Drivers

• Productivity growth: The simplest macroeconomic

theories dictate that the interest rate is pinned down

by growth in aggregate productivity. The idea is that

the rate of interest paid by a borrower must com-

pensate the lender for giving up on alternative use

of those funds, known as their “opportunity cost.”

Higher productivity growth increases the marginal

product of capital and drives up savers’ opportunity

cost, necessitating a higher interest rate to induce

them to lend (Cesa-Bianchi, Harrison, and Sajedi

2022; Mankiw 2022; Solow 1956).

• Demographics: Changes in fertility and mortality

rates have complex and time-varying effects on the

natural rate. Demographic forces have implications

for the economy’s growth rate, its dependency ratio,

and aggregate desired saving for longer retirement

(Auclert and others 2021; Carvalho, Ferrero, and

Nechio 2016; Gagnon, Johannsen, and López-Salido

2021; see Online Annex 2.3).

• Fiscal policy: Increased government borrowing can

lead to higher interest rates because more saving is

required to meet the increased demand for funds.

However, the extent to which this occurs also

depends on how much private investment is displaced

by the additional public debt (Eggertsson, Mehrotra,

and Robbins 2019; Rachel and Summers 2019).

• Market power and the labor share: The impact of

increased market power on the natural rate is ambigu-

ous. Increased market power typically depresses future

production and investment demand, weighing down

on interest rates. But it also reroutes dividends from

laborers to capital owners, with the impact on the

12

See also Rogoff, Rossi, and Schmelzing (2021) for an analysis of

real rate dynamics over the past 700 years.

13

See Eggertsson, Mehrotra, and Robbins (2019) and Mankiw

(2022) for recent reviews and Online Annex 2.3 for detailed descrip-

tion of the theoretical channels.

53International Monetary Fund | April 2023

CHAPTER 2

THE NATURAL RATE OF INTEREST: DRIVERS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

natural rate depending on the distribution of these

dividends across cohorts (Ball and Mankiw 2021;

Caballero, Farhi, and Gourinchas 2017b; Eggertsson,

Mehrotra, and Robbins 2019; Mankiw 2022; Natal

and Stoffels 2019; Platzer and Peruffo 2022).

• Other reasons: These include the effect of govern-

ment taxation on the profile of private consumption

and saving (Eggertsson, Mehrotra, and Robbins

2019; Platzer and Peruffo 2022), rising inequality

increasing the overall supply of savings because rich

people tend to save more than poor people (Mian,

Straub, and Sufi 2021a, 2021b, 2021c), and poten-

tial interactions between different channels.

Financial Drivers

• International capital flows and the scarcity of safe

assets: International spillovers from the integration

of global capital markets may have been powerful

drivers of the natural rate. Two main mechanisms

are at work. On one hand, high-growth emerging

markets provide alternative investment oppor-

tunities, resulting in capital outflows and raising

the natural rate in advanced economies (Clarida,

Galí, and Gertler 2002; Galí and Monacelli 2005;

Obstfeld and Rogoff 1997; Obstfeld 2021). On

the other hand, the supply of safe and liquid assets,

primarily US government bonds, has not kept pace

with fast-rising demand, especially from emerging

markets. Their ensuing scarcity may have driven

up their price and lowered their return (Bárány,

Coeurdacier, and Guibaud 2018; Bernanke 2005;

Caballero, Farhi, and Gourinchas 2008, 2016,

2017a, 2017b, 2021; Del Negro and others 2017;

Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen 2012).

• Risk aversion and leverage cycles: The quality attributed

to particularly safe and liquid assets (for example,

government bonds in advanced economies) gives rise

to a convenience yield, which is variable and likely

to increase when global stress leads to deleveraging

(Gourinchas, Rey, and Sauzet 2022). Given the safe

haven property of the US dollar, this is especially the

case for US Treasurys whose value increases in periods

of stress, providing protection to risk-averse interna-

tional investors (Gourinchas, Rey, and Govillot 2017).

A New Theoretical Framework

To compare the quantitative impact of these dif-

ferent forces, this chapter relies on a macroeconomic

model (PP) based on Platzer and Peruffo (2022).

is is an important novelty with respect to earlier

literature because the PP model includes in one unified

framework many of the mechanisms discussed in the

previous section and so can explain how the contri-

butions from each of the corresponding economic

forces change the natural rate. is approach avoids

double-counting and having to infer the impor-

tance of each driver from different models calibrated

separately.

14

PP is a “real” macroeconomic model, in the sense

that it abstracts from nominal and financial frictions

that typically underlie cyclical fluctuations. Similarly,

for tractability, uncertainty is assumed away. While

these are reasonable assumptions for the study of

medium- to long-term trends in the real interest rate,

the model is ill-equipped to analyze the impact of the

financial drivers discussed earlier.

15

Nonetheless, PP

still allows for foreign developments to affect domestic

interest rates through their implication for net interna-

tional capital flows.

PP is calibrated to represent eight major global

economies: the United States, Japan, Germany, the

United Kingdom, France, China, India, and Brazil.

ese are the five largest advanced economies and the

three largest emerging market and developing econ-

omies, which cover some 70 percent of global GDP.

Demographic developments, the age-earning profile,

the share of income going to the richest 10 percent,

productivity trends, the retirement age, average pen-

sion replacement rates, labor share, government debt,

and public expenditure inform the country-specific

calibrations.

Before turning to detailed model simulations,

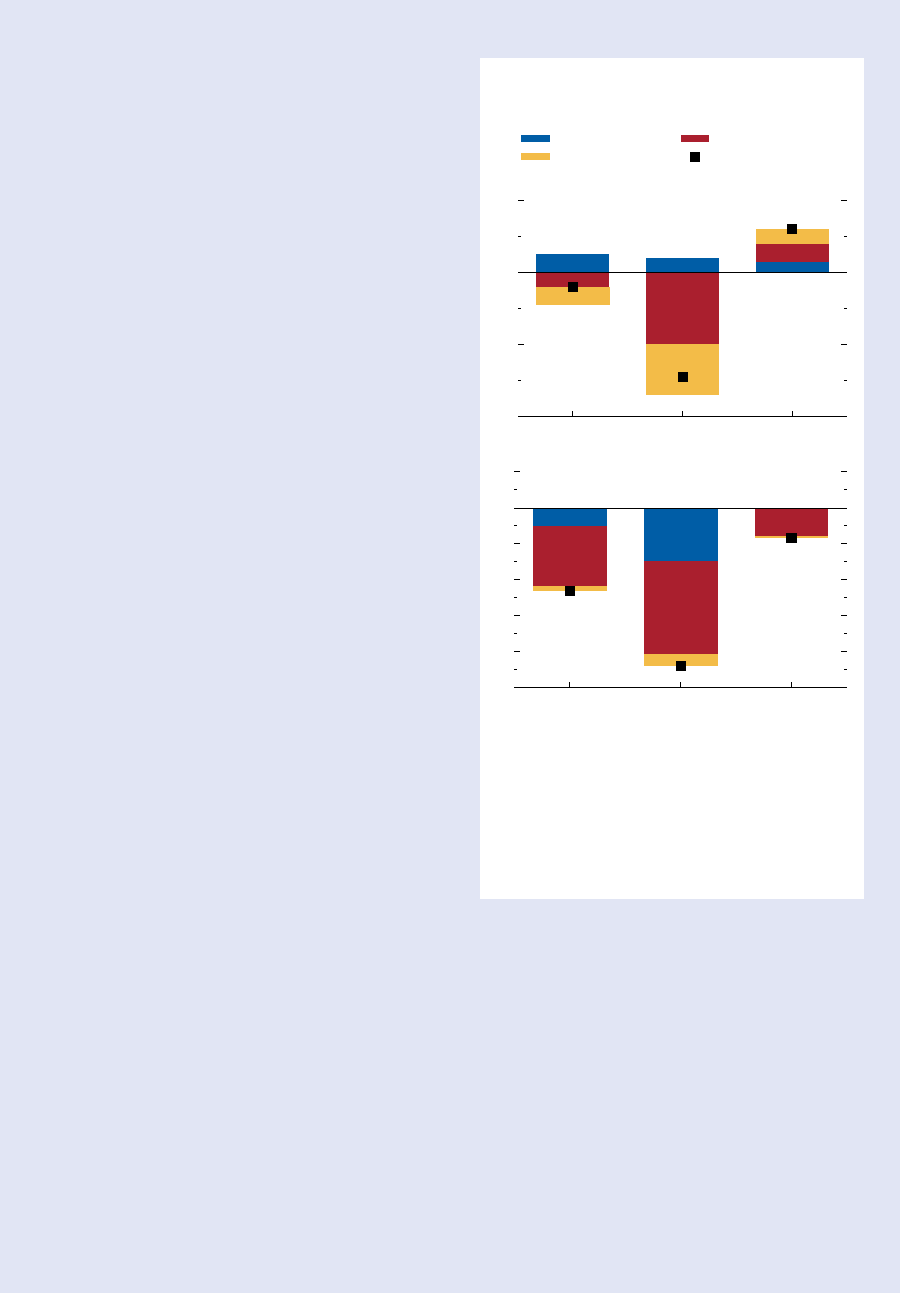

Figure 2.6 compares the overall decline in the natural

rate implied by the PP and HLW frameworks. e

striking similarity between the results obtained with two

very different approaches is reassuring. is mitigates

the uncertainty surrounding HLW point estimates while

bolstering confidence in the microeconomic structure of

the PP framework.

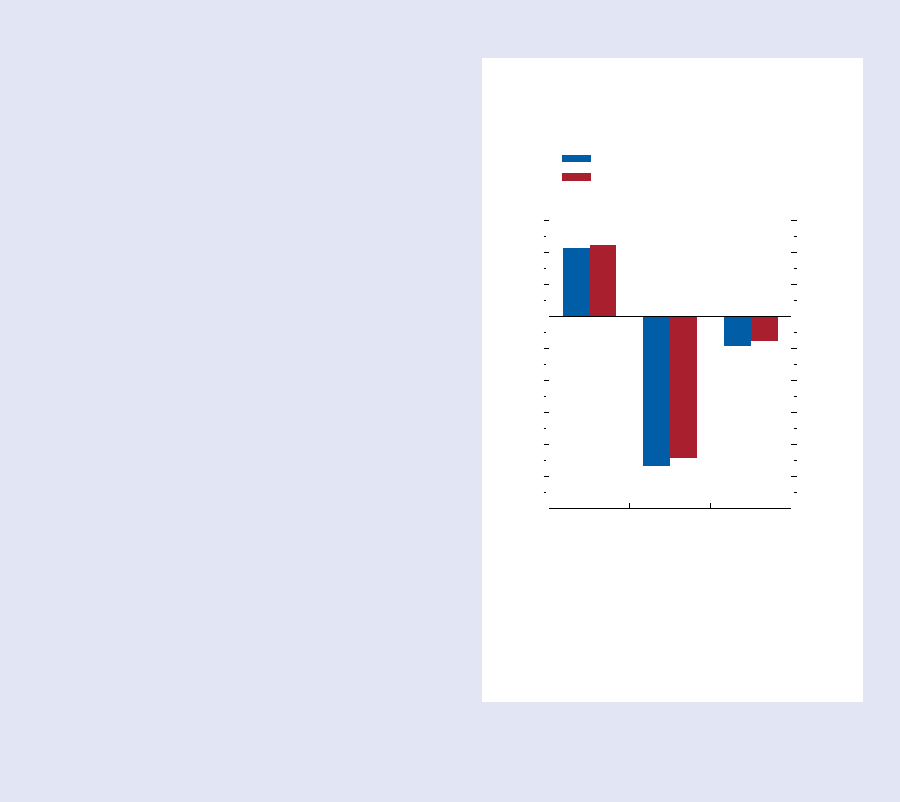

e first exercise for this model is to understand

why the natural rate has declined in the past several

decades. Figure 2.7 presents the estimated change in

the natural rate and its attribution to the different

fundamental forces for each of the eight countries.

14

Full details of the model are in Platzer and Peruffo (2022).

A description of specific calibration and simulations is in

Online Annex 2.3.

15

See the section “Alternative Scenarios” for quantification of the

impact of variations in the convenience yield.

54 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

While no factor clearly dominates over the past

40 years, a set of common forces has driven the natural

rate, explaining part of the international comovement.

All eight countries in the sample experienced

population aging contributing negatively to the change

in the natural rate. is effect was particularly large

in China, Japan, and Germany. Growth in total factor

productivity (TFP) declined in all advanced economies,

at times explaining far more than the final decline in

the natural rate. Fiscal policy is an important offset in

all economies, particularly Japan and Brazil. In Japan,

public debt increased by more than 200 percent of

GDP, lifting the natural rate by more than the negative

contributions from TFP growth or demographics.

In Brazil, it is mainly the large increase in public

consumption, financed by taxation, that explains the

positive contribution of the fiscal driver, even though

the increase in public debt also plays a role. e

contribution of net international capital flows, which

summarizes the net impact of global forces through

international spillovers (discussed in the context of

Figure 2.5), is significant but smaller and goes in the

expected direction.

16

e largest net negative effect

is found in the United States, potentially reflecting

that stockpiling of safe assets by emerging markets

more than offsets capital outflows drawn to attractive

investment opportunities abroad. In contrast, in Japan,

capital outflows seem to dominate, lifting the country’s

natural rate as excess domestic savings are invested in

faster-growing economies abroad. e picture is more

mixed in the three large emerging markets displayed

16

Note that while gross capital flows have increased over time as

capital accounts have liberalized, both in- and outflows have surged

since the 1970s.

Natural rate Kalman filter Natural rate structural model

Figure 2.6. Natural Rate Estimates: Model Comparison

(Percent)

Sources: Holston, Laubach, and Williams (2017); Platzer and Peruffo (2022); and

IMF staff calculations.

Note: The Kalman filter estimates are based on Holston, Laubach, and Williams

(2017). The estimates from the structural model are based on Platzer and Peruffo

(2022). The values from the structural model for 2015–19 are calibrated to overlap

with the Kalman filter estimates. The ranges show 90 percent confidence

intervals.

1. France 2. Germany

3. Japan

5. United States

4. United Kingdom

1975–79 2015–19

1975–79 2015–19

1975–79 2015–19

1975–79 2015–19

1975–79 2015–19

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

Demographics TFP growth

Fiscal Capital flows

Other Total change

Figure 2.7. Drivers of Natural Rate Changes from 1975–79 to

2015–19 for Selected Economies

(Percentage points)

–5

–4

–3

–2

–1

0

1

2

3

Sources: Platzer and Peruffo (2022); and IMF staff calculations.

Note: TFP = total factor productivity.

France Germany Japan United

Kingdom

United

States

Brazil China India

55International Monetary Fund | April 2023

CHAPTER 2

THE NATURAL RATE OF INTEREST: DRIVERS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

here (Box 2.3 analyzes the importance of international

spillovers for smaller emerging market and developing

economies).

17

The Outlook for the Natural Rate

So far, this chapter has focused on understanding

what has happened to the natural rate and why. While

interesting, this is perhaps less relevant for policy today

than a slightly different issue: What will happen to real

rates in the future?

The Baseline

e same framework used to understand the

drivers of the natural rate can also be used to convert

assumptions about those underlying drivers into pre-

dictions for the natural rate. e baseline projection

presented in Figure 2.8, panel 1, relies on conserva-

tive assumptions for the main drivers: (1) predicted

demographic trends follow United Nations population

projections, (2) public debt follows World Economic

Outlook (WEO) projections until 2028 (and remains

constant thereafter), and (3) all other drivers are

assumed fixed at their 2015–19 levels. In emerging

markets, (4) TFP growth is assumed to converge to

the advanced economies’ average over the long term,

as would be expected as countries get closer to the

technology frontier.

e simulation suggests that natural interest rates

are likely to stay close to pre-pandemic levels in

advanced economies. Because the demographic tran-

sition is already well underway, the residual negative

impact of further aging is expected to be moderate.

At the same time, higher public debt acts as a coun-

terweight, pushing up the natural rate. In emerging

markets, in contrast, the prognosis is for a significant

decline in natural rates. is is the consequence of

slowing productivity growth and an aging population;

in many emerging market economies, the demo-

graphic transition should accelerate in the decades

ahead. In China, for example, a steady decline in the

17

ere are also country-specific forces that drive idiosyncratic

movements in the natural rate. For example, the rise in inequality

during the past half-century has had a large negative impact on

the natural rate in the United States, even more than demographic

changes. Rising inequality is also relevant in India and Japan. e

change in market power is significant for India, which has experi-

enced a large decline in the labor share over recent decades, implying

a corresponding rise in market power in this chapter’s model.

Online Annex 2.3 provides further explanation.

natural rate by about 1.5 percentage points within

the next 30 years is projected, bringing it to about

zero in 2050.

ese projections assume that some degree of

segmentation remains between the capital markets

of advanced economies and emerging markets (see

Figure 2.2 and the analysis in Obstfeld 2021) and that

the balance of capital inflows and outflows stays as it

was in 2019.

Departures from these assumptions are used to craft

alternative scenarios.

Alternative Scenarios

e outlook for a given scenario is highly uncertain.

Many shocks could cause the natural rate to depart

from the baseline paths. And so these paths should

be thought of as illustrative, with a distribution of

future outcomes around them. Within this uncertain

outlook, some specific alternative scenarios stand out

Brazil China

France Germany

India Japan

United Kingdom United States

AE high debt

EM high debt

AE decline in convenience yield

AE higher labor share

Figure 2.8. Simulated Path for Natural Rate of Interest:

Baseline and Scenarios

1. Baseline

(Percent)

–1

0

1

2

3

4

2022 25 30 35 40 45 50

2. Alternative Scenarios

(Percentage point deviation from baseline)

–0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

2022 25 30 35 40 45 50

Sources: Platzer and Peruffo (2022); and IMF staff estimates.

Note: AEs are France, Germany, Japan, United Kingdom, and United States. EMs

are Brazil, China, and India. The lines in panel 2 represent the difference between

the scenarios and the baseline. The decline in convenience yield is simulated in a

version of the model with a positive convenience yield; see Online Annex 2.3.

AE = advanced economy; EM = emerging market economy.

56 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

as particularly germane to the current post-pandemic

conjuncture. (1) Government debt could drift higher,

(2) enthusiasm for holding safe and liquid public

debt could wane, (3) workers’ bargaining power could

increase, (4) deglobalization forces could intensify,

and (5) the energy transition could have important

implications for global saving, investment, and the

natural rate. ese alternative scenarios are reported

in Figure 2.8, panel 2, and in Boxes 2.1 and 2.2 and

are described briefly here. All in all, deviations are

expected to be relatively modest, spanning a range

of about 120 basis points centered on the baseline

scenario. Of course, more sizable effects could be envi-

sioned should combinations of these scenarios happen

simultaneously.

• Higher government debt: As households struggle

to keep up with rising energy expenses and the

ongoing impact of the pandemic, governments may

opt to provide greater financial assistance. Allowing

public debt to increase by 25 percent of GDP above

the baseline by 2050 would increase demand for

private savings and lift the natural rate; however, the

impact should not exceed 5 to 10 basis points for

most countries.

18

• Erosion of the convenience yield, leading to higher

borrowing costs for government in advanced

economies: If investors were to perceive advanced

economies’ government debt as less safe and less

liquid than in the past (for example, if the US

Congress failed to raise the debt ceiling), then the

premium they pay for holding this particular type

of asset would erode as portfolios are rebalanced;

in this scenario, it is assumed that the premium

would return to pre-2000 average levels.

19

This

decline in the convenience yield over the next three

decades would bring up natural rates in advanced

18

e only channel modeled here is the effect of higher

demand for loanable funds from the public sector lifting the

equilibrium interest rate. Higher public debt could in principle

also erode the convenience yield, with a significant effect on

sustainability. is is considered explicitly in the next section,

“Policy Implications.”

19

By considering yield spreads between safe and liquid govern-

ment bonds and the highest-quality corporate bonds, the chapter

focuses here on the spread that most closely reflects the notion

that the convenience yield measures the unique safety and liquidity

characteristics of a government bond (Del Negro and others

2017). Other possibilities include yield spreads with lower-quality

corporate bonds or the equity risk premium (Caballero, Farhi, and

Gourinchas 2017b).

economies (and lower corporate bond yields) by

about 70 basis points.

20

• Higher labor shares in advanced economies: Markups

have increased in the past several decades, raising

the share of income going to capital owners at the

expense of workers (Akcigit and others 2021). As

workers’ bargaining power continues to improve

following the post-pandemic transformation of the

labor market, a return to labor shares prevailing in

the mid-1970s in advanced economies would raise

the natural rate by 6 to 19 basis points by 2050.

• Energy transition: Transitioning to a cleaner and

more sustainable global economy by 2050, as

laid out in the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate

change, would push global natural rates lower in

the medium term because higher energy prices

bring down the marginal productivity of capital

and investment demand. For reasonable scenarios

based on the October 2020 WEO, the effects are

expected to be relatively modest: By 2050, natural

rates are expected to decline by 50 basis points

along a hump-shaped trajectory. If large investment

in low-emission capital and technology is financed

through budget deficits, natural rates could tempo-

rarily climb by 30 basis points (Box 2.1).

• Deglobalization: With increasing geopolitical ten-

sions, the risk of some form of international trade

fragmentation—higher trade barriers, sanctions,

and the like—is elevated. Lower international

trade would push down global output and desired

investment. The effect on the natural rate would

vary across regions, reflecting the shortening of

global value chains. The risk of trade fragmentation

is compounded by the risk of financial fragmenta-

tion (April 2023 Global Financial Stability Report),

whose effect on real interest rates will depend on

countries’ initial external position: Deficit coun-

tries will find it more difficult to finance their

current accounts, while surplus countries will

repatriate excess savings, bringing down the natural

20

e model does not capture the endogenous response of capital

flows to a change in preferences for government bonds by foreign

investors. However, this effect could be sizable for safe asset providers

such as the United States. To get a sense of the possible magnitude

of the effect, it is useful to look at gross foreign portfolio investments

in the United States, which increased by about 79 percent of GDP

(US Bureau of Economic Analysis) from their average level before

2000. Were these flows to reverse, simulations show that this could

result in an increase in the natural rate of roughly 100 basis points in

the United States by 2050.

57International Monetary Fund | April 2023

CHAPTER 2

THE NATURAL RATE OF INTEREST: DRIVERS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

interest rate. Effects are between a 40 basis point

decline and a 20 basis point increase, depending on

the region. For trade fragmentation, the effects are

expected to be smaller (Box 2.2).

Policy Implications

Overall, the simulations previously discussed indi-

cate that natural rates will likely remain at low levels

in advanced economies, while in emerging market

economies, they are expected to converge from above

toward advanced economies’ levels. ese patterns will

have important implications for both monetary and

fiscal policy.

Monetary Policy

Once inflation is brought back to target over the

coming years, which may require a protracted period of

high interest rates (Chapter 1), the implication for mon-

etary policy seems clear: Long-term forces suggest that

natural rates will remain low (in advanced economies) or

decline further (in emerging markets), which may limit

the ability of central banks to ease policy by lowering

nominal interest rates. As a result, monetary institutions

may have to resort to the same strategies they employed

in the decade before the pandemic, such as balance sheet

policy and forward guidance. In addition, if deflation-

ary dynamics take hold, many economies may become

trapped for an extended period in a suboptimal equi-

librium characterized by low growth and underemploy-

ment (Summers 2014). To address these challenges, a

larger stabilization role may have to be assigned to fiscal

policy, and coordination between fiscal and monetary

policy might even be necessary. Reopening the debate

about the appropriate level of inflation targets, weigh-

ing the cost of permanently higher inflation against the

benefit of enhanced monetary policy space, may also

be warranted (Blanchard 2023; Galí 2020; IMF 2010;

Chapter 2 of the April 2020 WEO).

Fiscal Policy

Concerns about debt sustainability have recently

resurfaced due to the sharp increase in government debt

following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and

the simultaneous rise in policy rates to combat high

inflation. In this context, the key factor for debt sustain-

ability analysis is the difference between the real rate of

interest (r) and the growth rate of the economy ( g). If

growth is higher than the real interest rate, governments

may be able to sustain higher primary budget deficits

without necessarily compromising debt sustainability.

e PP model used earlier in the chapter con-

sidered the impact of the fiscal policy stance on the

natural rate, given that public debt issuance increases

demand for loanable funds. is section studies the

implications of secular movements in the natural rate

for debt sustainability. e analysis relies on a partial

equilibrium framework based on recent work by Mian,

Straub, and Sufi (2022).

21

is framework takes the

natural interest rate and growth projections from the

PP model as given and assesses debt dynamics under

different scenarios for the eight advanced and emerging

market economies presented in the preceding section.

e framework assumes that savers prefer to hold

government debt due to its liquidity and safety

features or due to regulatory requirements. is

means government debt enjoys a premium in financial

markets relative to comparable assets, known in the

literature as the “convenience yield,” which effectively

translates into a discount extended to the govern-

ment on its borrowing costs (Krishnamurthy and

Vissing-Jorgensen 2012; Wiriadinata and Presbitero

2020). However, as the public sector accumulates more

debt, government securities become less attractive to

savers, and the borrowing costs for the government

increases: e convenience yield gets eroded. Because

the interest rate increases with the debt level in this

framework, there is a limit to the size of the primary

deficit governments can sustainably run in the long

term.

22

e sensitivity of interest rates to debt is

important in this context, and its implications are

discussed at the end of this section.

21

Online Annex 2.4 describes the framework in detail. Further

references can be found in Chapter 2 of the April 2022 WEO and

Caselli and others (2022). A framework in which both channels are

mutually operable would be ideal, but it would add a significant

layer of complexity to an already very detailed framework.

22

Of course, stabilizing the debt ratio is only one criterion for

debt sustainability. Furman and Summers (2020) and Blanchard

(2023) discuss stabilizing the debt service ratio, or debt service

costs as a percent of GDP, as an alternative. Chapter 2 of the

October 2021 Fiscal Monitor discusses the merit and limitations

of this approach. In a long-term steady state in which borrowing

costs are pinned down by the natural rate of interest, stabilizing the

debt-to-GDP ratio would also stabilize the debt service ratio. e

two measures would, however, diverge over the business cycle, espe-

cially if interest rates and growth rates move in opposite directions,

as is often the case in emerging markets.

58 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

e projections from the PP model and the

elasticity of the convenience yield to the level of the

debt-to-GDP ratio are used to identify the long-term

debt-stabilizing primary balance for each level of debt.

Given current primary balances, the amount of fiscal

consolidation needed is computed under the baseline

and two of the scenarios presented earlier (high debt

and 1970s labor share). Table 2.1 shows the amount of

fiscal consolidation needed for the United States and

China, the single largest representative of each country

group in our sample.

23

For the United States, consolidation of about

3.7 percentage points of GDP is needed under the

baseline. In the higher-debt scenario, more consoli-

dation is required, at about 3.9 percentage points of

GDP. Under the higher-labor-share scenario, the dif-

ference between the natural rate and long-term growth

becomes less favorable, so that slightly greater consol-

idation is required relative to the baseline. For China,

the needed consolidation is much greater. A deficit

reduction of about 7.6 percent of GDP is required to

stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio over the long term.

e large consolidation reflects China’s sizable primary

deficit of about 7.5 percent of GDP in 2022. In all

scenarios, it is assumed that fiscal adjustment can be

undertaken either in the near term or over the medium

term; the smaller the primary deficit in 2022, the

smaller the fiscal cost of waiting.

24

Inference about the fiscal space available to govern-

ments is of course uncertain. One important dimen-

sion of uncertainty relates to the sensitivity of interest

rates to debt. An increase in the sensitivity of interest

rates to debt essentially lowers the debt threshold at

which primary surpluses are required for sustainability

and thus erodes the fiscal space available to govern-

ments. Online Annex 2.4 conducts robustness analysis

around this parameter that highlights the importance

of building safety margins to account for changing

market conditions and investors’ risk perceptions

(Caselli and others 2022).

23

is exercise is repeated for the other six large advanced and

emerging market economies in Online Annex 2.4.

24

As noted earlier, this is a partial equilibrium exercise. Fiscal con-

solidation is bound to be more difficult if the effect of deficit reduc-

tion on real GDP is taken into account. Also, for China, the chapter

uses the definition of public debt in the World Economic Outlook

database, which uses a narrower perimeter of the general government

than IMF staff estimates in China Article IV reports. See the 2022

Article IV report on China for a reconciliation of the two estimates

and a debt sustainability assessment based on the broader perimeter

of the general government.

Conclusion

Following four decades of steady decline, real interest

rates appear to have increased in many countries in the

wake of the pandemic. While this uptick clearly reflects

recent monetary policy tightening, this chapter’s analysis

seeks to understand whether the long-term anchor—the

natural rate—has also shifted. is is of key importance

for the pricing of all assets (housing, bonds, equities)

and for monetary and fiscal policy. All else equal, higher

natural rates typically decrease fiscal space—that is,

higher primary surpluses (smaller deficits) are required

to stabilize debt ratios. But they also free up some mon-

etary policy space. Higher natural rates imply higher

nominal rates over the long term, providing central

banks with more space to react to negative demand

shocks without hitting the effective lower bound.

e chapter suggests that recent increases in real

interest rates are likely to be temporary. When inflation

is brought back under control, advanced economies’

central banks are likely to ease monetary policy and

bring real interest rates back toward pre-pandemic lev-

els. How close to those levels will depend on whether

alternative scenarios involving persistently higher

government debt and deficit or financial fragmentation

materialize. In large emerging markets, conservative

projections of future demographic and productivity

trends suggest a gradual convergence toward advanced

economies’ real interest rates.

25

25

Of course, structural policies that boost potential growth and

diminish inequalities, for example, will tend to lean against these

secular trends.

Table 2.1. Required Fiscal Adjustment under

Different Scenarios

(Changes in primary deficit, percentage points of GDP)

Scenarios

Baseline Higher Debt 1970s Labor Share

Near-Term Adjustment

United States –3.71 –3.94 –3.75

China –7.63 –7.69 –7.63

Additional Consolidation Needed for Medium-Term Adjustment (three years)

United States –0.17 –0.18 –0.17

China –0.47 –0.49 –0.47

Additional Consolidation Needed for Medium-Term Adjustment (five years)

United States –0.29 –0.32 –0.29

China –0.87 –0.93 –0.87

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: The required fiscal adjustment is the difference from the long-term debt-stabilization

level, calculated as the difference between the 2022 primary deficit from the World

Economic Outlook database and the model-based estimate of the primary deficit that

stabilizes debt to GDP at the long-term rates given projections for the natural rate of

interest and growth.

59International Monetary Fund | April 2023

CHAPTER 2

THE NATURAL RATE OF INTEREST: DRIVERS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

is means that the issues associated with the

“effective lower bound” constraint on interest rates

and “low (interest rates) for long” are likely to

resurface.

26

Unconventional policies through active

management of central bank balance sheets and

forward guidance may become standard stabilization

tools, even in emerging markets. Debates about the

appropriate level of inflation target may also reemerge

26

As discussed at length in Eggertsson and Woodford (2003) and

Adrian (2020).

as countries weigh the social cost of higher inflation

against the constraint of ineffective stabilization due

to the effective lower bound. In addition, perma-

nently lower real interest rates also increase fiscal

space—all else equal—and allow fiscal authorities to

take a more active role in stabilizing the economy,

provided fiscal sustainability is ensured (Chapter 2

of the April 2020 WEO). In this case, it is crucial

to clarify the scope and responsibilities of fiscal and

monetary authorities to avoid long-term damage to

the credibility of central banks.

60 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

Policy responses to a transition to a carbon-neutral

world will induce significant structural transformation

that will affect the natural rate (r *) via a number of

channels. is box highlights the crucial role of two

channels: the design of climate policies and the level of

international participation in their implementation.

A comprehensive and global policy package

intended to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 serves

as a benchmark, as simulated in Chapter 3 of the

October 2020 World Economic Outlook.

1

Carbon

taxes—aimed at achieving net-zero emissions by

2050—are imposed globally, starting at between $6

and $20 a metric ton of CO

2

(depending on the

country) and reaching $40 a ton in 2030 and between

$40 and $150 a ton in 2050. e package is fully

financed by the carbon tax revenues—25 percent

recycled toward social transfers, up to 70 percent for

green public infrastructure investment, and the rest

as subsidies to renewable energy sectors—making the

policy budget-neutral.

2

Maintaining budget neutrality

helps isolate the impact of the green transition on r *

absent debt-financed green investments. Although they

are subject to uncertainty and intended to be largely

illustrative, the results from simulating the policy

package yield several insights into how climate policies

can be expected to affect r *.

Different climate mitigation policies affect r* dif-

ferently. Acting alone, carbon taxes depress overall

investment and hence r * (Figure 2.1.1, panel 1). is

is because the carbon tax increases the overall cost

of energy, a complement in production to physical

capital. As a result of frictions, the associated decline

in carbon-intensive activities exceeds the investment

in renewable sources of energy and low-emission

production methods—especially in countries where

e authors of this box are Augustus Panton and

Christoph Ungerer.

1

Simulations are computed with the G-Cubed model, an

open-economy, multicountry macroclimate model (see Liu and

others 2020; McKibbin and Wilcoxen 1999).

2

e scenario differs from the investigation in Chapter 3 of

the October 2020 World Economic Outlook in two ways. First, it

assumes a budget-neutral design rather than deficit financing. Sec-

ond, given the large uncertainty surrounding the impact of green

public investment on output, the simulations take a conservative

approach and do not assume any direct productivity gains from

green public investment. Of course, any amount of progress in

total factor productivity would tend to lift the natural rate.

Net

Avoided damage

Carbon tax

Green infrastructure

Green subsidies

Transfers

Deficit-financed package

1

Budget-neutral package

2

Advanced economies

Top five emitters

Global

Figure 2.1.1. The Global Natural Rate of

Interest and the Green Transition

(Global average, percentage point deviation from

baseline)

Sources: G-Cubed model, version 164; and IMF staff

calculations.

1

The deficit-financed package is based on Chapter 3 of the

October 2020 World Economic Outlook (WEO) but is agnostic

on total factor productivity effects: front-loaded and deficit-

financed green public investment of 1 percent of GDP in the

first 10 years, 80 percent green subsidies to renewable

sectors, carbon tax revenues recycled to households (1/4),

and public debt reduction (3/4).

2

Budget-neutral package uses carbon tax revenues to

finance green public investment, green subsidies, and

household transfers in the same proportion as in Chapter 3

of the October 2020 WEO, but with a much smaller revenue

envelope.

–1.0

–0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

2023 28 33 38 43 48 55

1. Budget-Neutral Climate Policy Package

2. Impact of Deficit-Financed versus

Budget-Neutral Policies

3. Budget-Neutral Package with Partial

Participation

2023

28 33 38 43 48

55

2023

28

33 38 43 48

55

–0.6

–0.4

–0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

–0.6

–0.4

–0.2

0.0

0.2

Box 2.1. The Natural Rate of Interest and the Green Transition

61International Monetary Fund | April 2023

CHAPTER 2

THE NATURAL RATE OF INTEREST: DRIVERS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

production is carbon intensive. In contrast, public

investment in green infrastructure and subsidies

to renewable energy positively affect investment,

pushing up r *. It is also worth noting that climate

mitigation helps avoid climate-change-related dam-

ages, boosting productivity growth with respect to a

business-as-usual baseline and raising r *.

e net impact on r* depends on the associated

overall fiscal impulse. Panel 2 of Figure 2.1.1 shows an