1

March 31, 2023

NOTE TO: Medicare Advantage Organizations, Prescription Drug Plan Sponsors, and

Other Interested Parties

Announcement of Calendar Year (CY) 2024 Medicare Advantage (MA) Capitation Rates

and Part C and Part D Payment Policies

In accordance with section 1853(b)(1) of the Social Security Act, we are notifying you of the

annual capitation rate for each Medicare Advantage (MA) payment area for CY 2024 and the

risk and other factors to be used in adjusting such rates.

In response to our request for comments on the Advance Notice of Methodological Changes for

CY 2024 MA Capitation Rates and Part C and Part D Payment Policies (CY 2024 Advance

Notice), published on February 1, 2023, CMS received submissions from professional

organizations, MA and Part D sponsors, advocacy groups, physicians, state Medicaid agencies,

pharmaceutical manufacturers, pharmacy benefit managers, pharmacies, and other interested

persons. The Rate Announcement describes and responds to all of the substantive comments

received.

After considering all comments received, we are finalizing policies in the Announcement of CY

2024 MA Capitation Rates and Part C and Part D Payment Policies (CY 2024 Rate

Announcement) that reflect CMS’ commitment to ensuring that people with Medicare receive

equitable, affordable, high quality, and whole-person care now and in the future, especially the

most vulnerable. The policies in the CY 2024 Rate Announcement are an important step in our

efforts to make sure the MA program meets the health care needs of all beneficiaries while

improving the quality and long-term stability of the Medicare program. The CY 2024 Rate

Announcement finalizes an important transition to an updated risk adjustment model that

implements a set of commonsense, clinically-based technical updates needed to keep MA

payments up-to-date and to improve payment accuracy to MA plans.

Specifically, the updated risk adjustment model is developed using ICD-10 codes to align with

the rest of the health care system, which has been using ICD-10 since 2015. It also incorporates

newer data – the current MA risk adjustment model is calibrated with 2014 diagnosis data and

2015 FFS expenditure data and the new model uses 2018 diagnosis data and 2019 expenditure

data. Finally, the revised model includes clinically-based adjustments to ensure that conditions

included in the model are stable predictors of costs. These adjustments help ensure payments

accurately reflect what it costs to care for beneficiaries and make the model less susceptible to

discretionary coding, which can lead to excess payments to MA plans. This is consistent with

updates we have done in the past where we removed or reclassified codes disproportionately

coded in MA compared to Medicare FFS to avoid wasteful spending.

2

Together, these updates improve the model’s ability to predict the cost of care and ensure MA

risk-adjusted payments are as accurate as possible, which ultimately makes sure MA plans are

paid enough to deliver the benefits that their enrollees are entitled to.

The capitation rate tables for 2024 and supporting data are posted on the CMS website at

https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health- Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Ratebooks-and-

Supporting-Data.html. The statutory component of the regional benchmarks, qualifying counties,

and each county’s applicable percentage are also posted on this section of the CMS website.

Attachment I of the Rate Announcement shows the final estimates of the National Per Capita

MA Growth Percentage for 2024 and the National Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Growth

Percentage for 2024, used to calculate the 2024 capitation rates. As discussed in Attachment I,

the final estimate of the National Per Capita MA Growth Percentage for combined aged and

disabled beneficiaries is 1.60 percent, and the final estimate of the FFS Growth Percentage is

2.45 percent. Attachment II provides a set of tables that summarizes many of the key Medicare

assumptions used in the calculation of the growth percentages.

Section 1853(b)(4) of the Social Security Act requires CMS to release county-specific per capita

FFS expenditure information on an annual basis, beginning with March 1, 2001. In accordance

with this requirement, FFS data for CY 2021 were posted on the above website with the Advance

Notice.

Attachment II details the key assumptions and financial information behind the growth

percentages presented in Attachment I.

Attachment III presents responses to Part C payment-related comments on the CY 2024 Advance

Notice.

Attachment IV presents responses to Part D payment-related comments on the Advance Notice.

Attachment V provides the final Part D benefit parameters and details how they are updated.

Attachment VI presents responses to comments on updates for MA and Part D Star Ratings.

Attachment VII contains economic information for significant provisions in the CY 2024 Rate

Announcement.

Attachment VIII contains the CMS-HCC Risk Adjustment Factor and Predictive Ratio tables.

Key Updates from the Advance Notice

Growth Percentages: Attachment I provides the final estimates of the National Per Capita MA

Growth Percentage and the FFS Growth Percentage, also called growth rates, upon which the

capitation rates are based, and information on deductibles for Medical Savings Accounts. Each

year for the Rate Announcement, CMS updates the growth rates to be based on the most current

3

estimate of per capita costs, based on the available historical program experience and projected

trend assumptions at that time. The growth rates change between proposed and final as CMS

incorporates updated data and assumptions. This year, the change in growth rates from the

Advance Notice to the Rate Announcement is due to several key factors, including: additional

CY 2022 experience data that was lower than previously projected, updated modeling to account

for the effects of COVID-19 and other programmatic and demographic changes, lower morbidity

from excess COVID-related deaths, lower total spending by explicitly modeling the shift of hip

and knee replacements from inpatient to outpatient setting, and updated modeling of the effect of

a greater share of dual beneficiaries enrolling in MA. For more information on the overall change

in growth rates, please see the Fact Sheet released in the Newsroom section of the CMS.gov

website that accompanies this Rate Announcement.

Technical Update to Medical Education Payments in the Non-ESRD USPCC Baseline:

CMS is finalizing the technical update to remove MA-related indirect medical

education and direct graduate medical education costs (described in the CY 2024

Advance Notice) from the historical and projected expenditures supporting the final

estimates (being released in this Rate Announcement) of the non-ESRD FFS USPCCs.

The Secretary has directed the CMS Office of the Actuary (OACT) to phase in this

technical update to the USPCCs over a 3-year period beginning with the CY 2024

ratebook, with 33% of the medical education adjustment applied to the USPCCs in

2024. We expect 67% of the 2025 medical education adjustment to be applied in 2025

and 100% of the 2026 value to be applied in 2026.

Calculation of FFS Costs: The Secretary has directed the CMS Office of the Actuary to adjust

the FFS experience for beneficiaries enrolled in Puerto Rico to reflect the propensity of “zero–

dollar” beneficiaries nationwide.

CMS-Hierarchical Condition Categories (CMS-HCC) Risk Adjustment Model (Non-PACE):

CMS is finalizing the updated risk adjustment model proposed in the CY 2024 Advance

Notice, but will phase it in over 3 years. For CY 2024, risk scores will be calculated as a blend

of 67% of the risk scores calculated with the current model (the 2020 model) and 33% of the

risk scores calculated with the updated model (the 2024 model). For CY 2025, we expect risk

scores to be calculated as a blend of 33% of the risk scores calculated with the 2020 model and

67% of the risk scores calculated with the 2024 model, and for CY 2026, we expect 100% of

the risk scores to be calculated with the 2024 model.

Frailty Adjustment for Fully Integrated Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (FIDE SNPs): CMS is

finalizing frailty factors that do not include the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers

and Systems (CAHPS) survey weight, which is an adjustment that can be used to account for

potential non-response bias. This weight was proposed to be included in the frailty factor

calculation in the CY 2024 Advance Notice. CMS will implement FIDE SNP frailty factors

consistent with the updated CMS-HCC risk adjustment model being finalized for CY 2024. Also,

4

consistent with CMS’ proposal to blend risk scores for CY 2024 (67% current model and 33%

updated model), a blended frailty score for FIDE SNPs will be compared with PACE frailty

calculated in the same manner to determine whether that FIDE SNP has a similar average level

of frailty as PACE. The final frailty factors for CY 2024 can be found in Section L.

Policies Adopted as Described

As in past years, policies in the Advance Notice that are not modified or retracted in the Rate

Announcement become effective for the upcoming payment year. Clarifications in the Rate

Announcement supersede information in the Advance Notice and prior Rate Announcements

as they apply for payment year 2024.

MA Benchmark, Quality Bonus Payments, and Rebate: We will continue to implement the

methodology, as described in the CY 2024 Advance Notice, used to derive the benchmark

county rates, how the qualifying bonus counties are identified, and the applicability of the Star

Ratings.

Location of Network Areas for Private Fee-for-Service (PFFS) Plans in Plan Year 2025: The list

of network areas for plan year 2025 is available on the CMS website at https://www.cms.gov/

Medicare/Health-Plans/PrivateFeeforServicePlans/NetworkRequirements.html.

Direct Graduate Medical Education (DGME) Carve-out Applied to Average Geographic

Adjustments (AGAs): As in past years, we will continue carving out FFS DGME amounts

from the MA capitation rates. (This is different than the technical update related to medical

education payments on behalf of MA enrollees in the Non-ESRD USPCC baseline discussed

above.)

Organ Acquisition Costs for Kidney Transplants: We will continue carving out Kidney

Acquisition Costs (KAC) from the MA capitation rates.

Indirect Medical Education (IME) Phase Out Applied to AGAs: We will continue phasing out

FFS IME amounts from the MA capitation rates.

MA End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Rates: We will continue to set MA ESRD rates on a

state basis.

MA Employer Group Waiver Plans (EGWPs): We will continue to use the payment

methodology as described in the Advance Notice, but with the finalized bid-to-benchmark

ratios for 2024 MA EGWP Payment rates as indicated in the table below. These bid-to-

benchmark ratios are weighted by February 2023 enrollment, including retroactive enrollment

5

adjustments made in March 2023 to the February 2023 enrollment file, due to a system

processing error.

1

Applicable Percentage

Bid to Benchmark Ratio

0.95

78.5%

1

77.2%

1.075

76.6%

1.15

76.8%

CMS-HCC Risk Adjustment Model (PACE): For CY 2024, CMS will continue to use the 2017

CMS-HCC risk adjustment model and associated frailty factors to calculate risk scores for

participants in PACE organizations.

CMS-HCC ESRD Risk Adjustment Models:

• For Non-PACE Organizations: For CY 2024, CMS will continue to use the 2023 CMS-

HCC ESRD risk adjustment models to calculate risk scores for beneficiaries in dialysis,

transplant, and post-graft status.

• For PACE Organizations: For CY 2024, CMS will continue to use the 2019 CMS-HCC

ESRD risk adjustment models to calculate risk scores for participants in PACE

organizations with ESRD.

Frailty Adjustment for PACE Organizations: For CY 2024, CMS will continue to use the frailty

factors associated with the 2017 CMS-HCC model (as displayed in Table II-6 of the CY 2024

Advance Notice) to calculate frailty scores for PACE organizations.

Medicare Advantage Coding Pattern Difference Adjustment: For CY 2024, CMS will continue

to apply the statutory minimum MA coding pattern difference adjustment factor of 5.90 percent.

Final 2024 Normalization Factors:

CMS will finalize the 2024 Normalization Factor methodologies as proposed in the Advance

Notice.

For the three CMS-HCC risk adjustment models with a 2019 or 2020 denominator listed below,

CMS will calculate the normalization factors using a five-year linear slope methodology and

updated average FFS risk scores for 2018 through 2022, but continuing to exclude the 2021 risk

score.

• 2024 CMS-HCC model (for non-PACE organizations), for blended risk score

calculations: 1.015

1

For more information, see the HPMS memorandum dated January 31, 2023 regarding the February 2023 MARx plan payment.

6

• 2023 CMS-HCC ESRD dialysis model (for non-PACE organizations): 1.022

• 2023 CMS-HCC ESRD functioning graft model (for non-PACE organizations): 1.028

For the four CMS-HCC risk adjustment models with a 2015 denominator listed below and the

RxHCC models, CMS will calculate the normalization factors using a five-year linear slope

methodology and historical FFS risk scores (2016 through 2020), without including the 2021 and

2022 risk scores.

• 2020 CMS-HCC model (for non-PACE organizations), for blended risk score

calculations: 1.146

• 2017 CMS-HCC model (for PACE organizations): 1.159

• 2019 CMS-HCC ESRD dialysis model (for PACE organizations): 1.100

• 2019 CMS-HCC ESRD functioning graft model (for PACE organizations): 1.159

• 2023 RxHCC model (for non-PACE organizations): 1.063

• 2020 RxHCC model (for PACE organizations): 1.084

Sources of Diagnoses for Risk Scores calculated with CMS-HCC and CMS-HCC ESRD Risk

Adjustment Models:

• For Non-PACE organizations: CMS will continue the policy adopted in the CY 2023

Rate Announcement to calculate risk scores for payment to MA organizations and certain

demonstrations using only risk adjustment-eligible diagnoses from encounter data and

FFS claims.

• For PACE organizations: CMS will continue using the same method of calculating risk

scores that we have been using since CY 2015, which is to pool risk adjustment-eligible

diagnoses from the following sources to calculate a single risk score (with no weighting):

(1) encounter data, (2) Risk Adjustment Processing System (RAPS) data, and (3) FFS

claims.

RxHCC Risk Adjustment Models:

• For Non-PACE Organizations: For CY 2024, we will continue to use the 2023 RxHCC

risk adjustment model to adjust direct subsidy payments for Part D benefits offered by

stand-alone Prescription Drug Plans (PDPs) and Medicare Advantage-Prescription

Drug Plans (MA-PDs).

• For PACE Organizations: For CY 2024, CMS will continue to use the 2020 RxHCC

risk adjustment model to calculate Part D risk scores.

Source of Diagnoses for Risk Scores calculated with the RxHCC Risk Adjustment Models:

7

• For Non-PACE organizations: CMS will continue the policy adopted in the CY 2023

Rate Announcement to calculate Part D risk scores using only risk adjustment-eligible

diagnoses from encounter data and FFS claims.

• For PACE organizations: CMS will continue using the same method of calculating risk

scores that we have been using since CY 2015, which is to pool risk adjustment-eligible

diagnoses from the following sources to calculate a single risk score (with no weighting):

(1) encounter data, (2) RAPS data, and (3) FFS claims.

Inflation Reduction Act Updates: CMS will implement the changes to the Part D drug benefit

made by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 as described in the CY 2024 Advance Notice:

• Cost sharing for covered Part D drugs will be eliminated for beneficiaries in the

catastrophic phase of coverage beginning in CY 2024.

• Beginning in CY 2024, the low-income subsidy program (LIS) under Part D will

increase the income limits for the full LIS benefit from 135 percent of the federal poverty

limit (FPL) to 150 percent of the FPL. Medicare beneficiaries earning between 135

percent and 150 percent of the FPL in CY 2024, who meet the resources requirements

under either sections 1860D-14(a)(3)(D) or (E) of the Act, and who would have been

eligible for the partial low-income premium and cost-sharing subsidies and a reduced

deductible under section 1860D-14(a)(2) of the Act had the IRA not been enacted, will be

eligible for full low-income premium and cost-sharing subsidies and a $0 deductible.

• For CY 2024, the deductible will continue not to apply to any Part D covered insulin

product. Also, in the initial coverage phase and the coverage gap phase, cost sharing must

not exceed the applicable copayment amount, which for CY 2024 is $35 for a month’s

supply of each covered insulin product.

2

• For CY 2024, the deductible will continue not to apply to any adult vaccine

recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Also, the

statute requires these vaccines to be exempt from any co-insurance or other cost sharing,

including cost sharing for vaccine administration and dispensing fees for such products,

when administered in accordance with ACIP’s recommendation, for beneficiaries in the

initial coverage and coverage gap phases.

3

• Beginning in CY 2024, the base beneficiary premium (BBP) growth will be held to no

more than 6 percent by statute. The BBP for Part D in 2024 will be the lesser of the BBP

2

The elimination of the deductible for each Part D covered insulin product and implementation of cost-sharing capped at $35 for

a month’s supply of each Part D covered insulin product has been effective as of January 1, 2023. See HPMS Memorandum,

Contract Year 2023 Program Guidance Related to Inflation Reduction Act Changes to Part D Coverage of Vaccines and Insulin,

September 26, 2022.

3

The elimination of the deductible and cost sharing for any adult vaccine recommended by ACIP has been effective as of

January 1, 2023. See HPMS Memorandum, Contract Year 2023 Program Guidance Related to Inflation Reduction Act Changes

to Part D Coverage of Vaccines and Insulin, September 26, 2022.

8

for 2023 increased by 6 percent or the amount that would otherwise apply under the

original methodology if the IRA were not enacted.

Annual Adjustments to Medicare Part D Benefit Parameters in 2024: We will update the defined

standard benefit deductible amount, initial coverage limit, and out-of-pocket (OOP) threshold, by

multiplying the CY 2023 amounts by the CY 2024 Annual Percentage Increase (API) and

rounding as specified by the statute.

Part D Calendar Year Employer Group Waiver Plans Prospective Reinsurance Amount: We are

maintaining the Part D Calendar Year EGWP prospective reinsurance policy as discussed in the

CY 2024 Advance Notice. The average per member per month (PMPM) actual reinsurance

amount paid to Part D Calendar Year EGWPs for the most recently reconciled payment year,

which for purposes of CY 2024 is CY 2021, was $71.09.

Part D Risk Sharing: We will apply no changes to the current threshold risk percentages for CY

2024.

Retiree Drug Subsidy Amounts: We will use the same methodology as in prior years to update

the cost threshold and cost limit for qualified retiree prescription drug plans.

/ s /

Meena Seshamani, M.D., Ph.D.

Director, Center for Medicare

I, Jennifer Wuggazer Lazio, am a Member of the American Academy of Actuaries. I meet the

Qualification Standards of the American Academy of Actuaries to render the actuarial opinion

contained in this Rate Announcement. My opinion is limited to the following sections of this

Rate Announcement: The growth percentages and United States per capita cost estimates

provided and discussed in Attachments I, II and III; the qualifying county determination,

calculations of Fee-for-Service cost, direct graduate medical education carve-out, kidney

acquisition cost carve-out, IME phase out, MA benchmarks, EGWP rates, and ESRD rates

discussed in Attachment III; the Medicare Part D Benefit Parameters: Annual Adjustments for

Defined Standard Benefit in 2024 described in Attachments IV and V; and the economic

information contained in Attachment VII. As noted in Attachment III, the Secretary has directed

the CMS Office of the Actuary to phase in the MA medical education technical correction to the

USPCCs that are used in determining the growth percentages.

/ s /

Jennifer Wuggazer Lazio, F.S.A., M.A.A.A.

Director

Parts C & D Actuarial Group

Office of the Actuary

9

Attachments

10

2024 RATE ANNOUNCEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS

Announcement of Calendar Year (CY) 2024 Medicare Advantage (MA) Capitation Rates

and Part C and Part D Payment Policies..............................................................................1

Key Updates from the Advance Notice .....................................................................................2

Policies Adopted as Described...................................................................................................4

Attachment I. Final Estimates of the National Per Capita Growth Percentage and the

National Medicare Fee-for-Service Growth Percentage for Calendar Year 2024.............13

Attachment II. Key Assumptions and Financial Information........................................................15

Attachment III. Responses to Public Comments on Part C Payment Policy.................................28

Section A. General Comments.................................................................................................28

Section B. Estimates of the MA and FFS Growth Percentages for 2024 ................................30

Section C. MA Benchmark, Quality Bonus Payments, and Rebate ........................................44

Section D. Calculation of Fee-for-Service Costs.....................................................................45

Section E. Direct Graduate Medical Education .......................................................................55

Section F. Organ Acquisition Costs for Kidney Transplants...................................................55

Section G. IME Phase Out.......................................................................................................55

Section H. MA ESRD Rates ....................................................................................................55

Section I. MA Employer Group Waiver Plans ........................................................................63

Section J. CMS-HCC Risk Adjustment Model for CY 2024 ..................................................65

Section K. End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Risk Adjustment Models for CY 2024 .........115

Section L. Frailty Adjustment for Fully Integrated Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans

(FIDE SNPs) and PACE Organizations .......................................................................116

Section M. Medicare Advantage Coding Pattern Adjustment...............................................120

Section N. Normalization Factors..........................................................................................123

Section O. Sources of Diagnoses for Risk Score Calculation for CY 2024 ..........................127

Attachment IV. Responses to Public Comments on Part D Payment Policy...............................128

Section D. Medicare Part D Benefit Parameters: Annual Adjustments for Defined

Section E. Part D Calendar Year Employer Group Waiver Plans Prospective

Section A. RxHCC Risk Adjustment Model .........................................................................128

Section B. Sources of Diagnoses for Part D Risk Score Calculation for CY 2024 ...............130

Section C. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 Part D Benefit Design Changes .......................130

Standard Benefit in 2024..............................................................................................131

Reinsurance Amount ....................................................................................................132

Section F. Part D Risk Sharing ..............................................................................................133

Attachment V. Final Updated Part D Benefit Parameters for Defined Standard Benefit, Low-

Income Subsidy, and Retiree Drug Subsidy ....................................................................134

Section A. Annual Percentage Increase in Consumer Price index ........................................137

Section B. Calculation Methodology.....................................................................................137

11

Section C. Annual Percentage Increase in Average Expenditures for Part D Drugs per

Eligible Beneficiary (API) ...........................................................................................139

Section D. Estimated Total Covered Part D Spending at Out-of-Pocket Threshold for

Applicable Beneficiaries ..............................................................................................140

Section E. Retiree Drug Subsidy Amounts............................................................................143

Attachment VI. Updates for Part C and D Star Ratings ..............................................................144

Part C and D Star Ratings and Future Measurement Concepts .............................................144

Reminders for 2024 Star Ratings...........................................................................................144

Measure Updates for 2024 Star Ratings ................................................................................145

Extreme and Uncontrollable Circumstances Policy for the 2024 Star Ratings .....................150

Changes to Existing Star Ratings Measures for the 2023 Measurement Year and Beyond..152

Display Measures...................................................................................................................162

Potential New Measure Concepts and Methodological Enhancements for Future Years .....169

Attachment VII. Economic Information for the CY 2024 Rate Announcement .........................179

Section A. Changes in the Payment Methodology for Medicare Advantage and PACE

for CY 2024..................................................................................................................179

A1. Medicare Advantage and PACE non-ESRD Ratebook ............................................179

A2. Indirect Medical Education (IME) Phase Out...........................................................179

A3. Medicare Advantage and PACE ESRD Ratebooks ..................................................180

A4. CMS-HCC Risk Adjustment Model .........................................................................180

A5. ESRD Risk Adjustment ............................................................................................181

A6. Frailty Adjustment for FIDE SNPs...........................................................................181

A7. MA Coding Pattern Adjustment ...............................................................................181

A8. Normalization............................................................................................................181

Section B. Changes in the Payment Methodology for Medicare Part D for CY 2024 ..........181

B1. Part D Risk Adjustment Model .................................................................................181

B2. Annual Percentage Increase for Part D Parameters ..................................................182

Attachment VIII. CMS-HCC Risk Adjustment Factors & Predictive Ratio Tables....................183

Table VIII-2. 2024 CMS-HCC Model Relative Factors for Aged and Disabled New

Table VIII-3. 2024 CMS-HCC Model Relative Factors for New Enrollees in Chronic

Table VIII-5. Predictive Ratios by Deciles of Predicted Risk (sorted low to high): Non-

Table VIII-6. Predictive Ratios by Deciles of Predicted Risk (sorted low to high): Non-

Table VIII-1. 2024 CMS-HCC Model Relative Factors for Continuing Enrollees...............183

Enrollees.......................................................................................................................193

Condition Special Needs Plans (C-SNPs)....................................................................194

Table VIII-4. 2024 CMS-HCC Model with Disease Hierarchies..........................................195

Dual, Aged (Age >=65) Continuing Enrollee ..............................................................197

Dual, Disabled (Age <65) Continuing Enrollee...........................................................197

12

Table VIII-7. Predictive Ratios by Deciles of Predicted Risk (sorted low to high): Full

Benefit Dual, Aged (Age >=65) Continuing Enrollee .................................................198

Table VIII-8. Predictive Ratios by Deciles of Predicted Risk (sorted low to high): Full

Benefit Dual, Disabled (Age <65) Continuing Enrollee ..............................................198

Table VIII-9. Predictive Ratios by Deciles of Predicted Risk (sorted low to high): Partial

Benefit Dual, Aged (Age >=65) Continuing Enrollee .................................................199

Table VIII-10. Predictive Ratios by Deciles of Predicted Risk (sorted low to high):

Partial Benefit Dual, Disabled (Age <65) Continuing Enrollee...................................199

Table VIII-11. Predictive Ratios by Deciles of Predicted Risk (sorted low to high):

Institutional Continuing Enrollee .................................................................................200

Aged + Disabled

Dialysis–only ESRD

Current projected 2024 FFS USPCC

$1,105.10

$9,544.97

Prior projected 2023 FFS USPCC

1,078.63

9,332.69

Percent change

2.45 %

2.27 %

13

Attachment I. Final Estimates of the National Per Capita Growth Percentage and the

National Medicare Fee-for-Service Growth Percentage for Calendar Year 2024

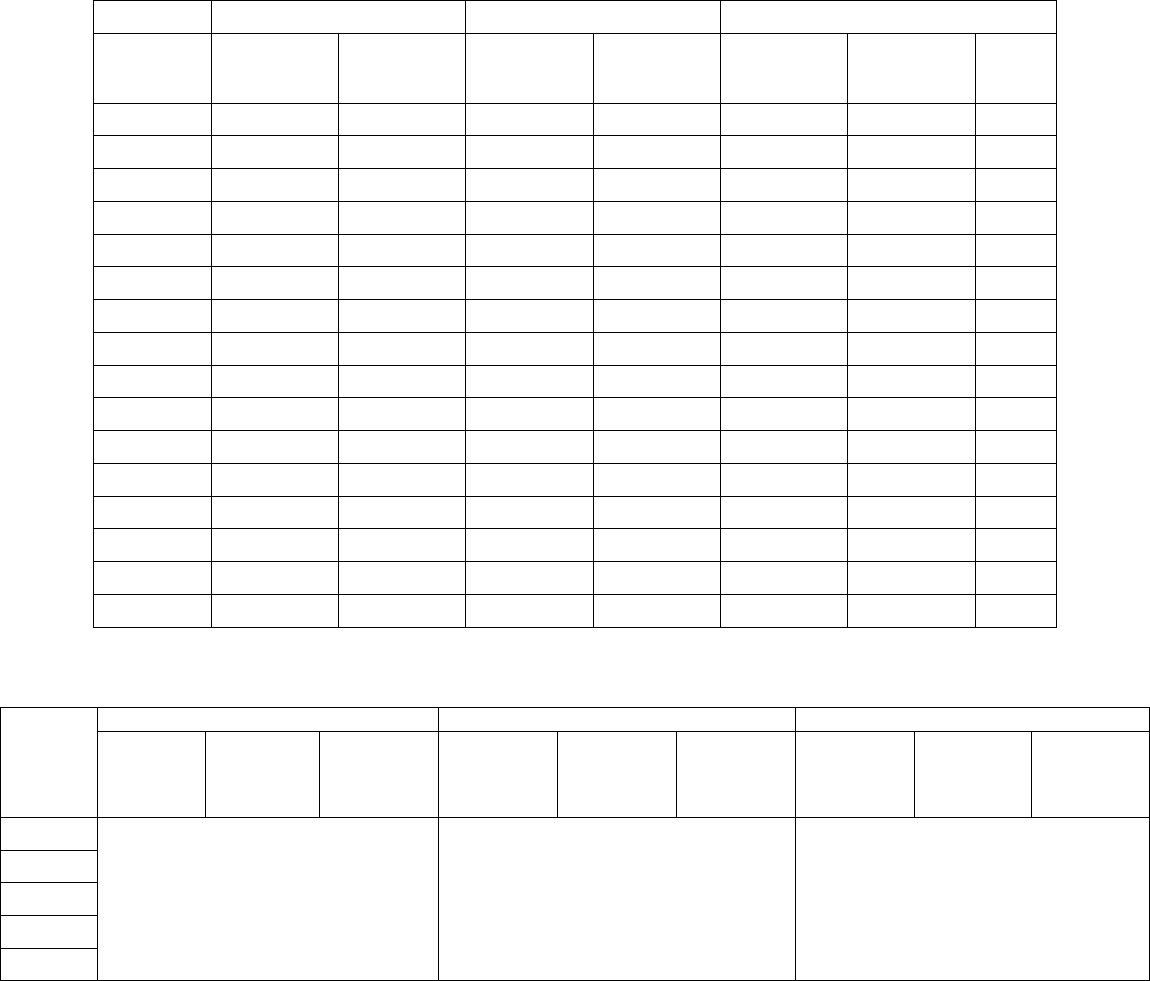

Table I-1 below shows the National Per Capita MA Growth Percentage (NPCMAGP) for 2024.

An adjustment of -1.77 percent for the combined aged and disabled cohort is included in the

NPCMAGP to account for corrections to prior years’ estimates as required by section

1853(c)(6)(C). The combined aged and disabled change is used in the development of the

ratebook.

Table I-1. Increase in the National Per Capita MA Growth Percentages (NPCMAGP) for

2024

Prior increases

Current increases

NPCMAGP for 2024

with §1853(c)(6)(C)

adjustment

1

2003 to 2023

2003 to 2023

2023 to 2024

2003 to 2024

Aged + Disabled

109.238 %

105.537 %

3.432 %

112.590%

1.60 %

1

Current increases for 2003-2024 divided by the prior increases for 2003-2023.

Table I-2 below provides the change in the FFS United States Per Capita Cost (USPCC), which

was used in the development of the county benchmarks. The percentage change in the FFS

USPCC is shown as the current projected FFS USPCC for 2024 divided by projected FFS

USPCC for 2023 as estimated in the 2023 Rate Announcement released on April 04, 2022.

Table I-2. FFS USPCC Growth Percentage for CY 2024

Table I-3 below shows the monthly actuarial value of the Medicare deductible and coinsurance

for 2023 and 2024. In addition, for 2024, the actuarial value of deductibles and coinsurance is

being shown for non-ESRD only, since MA plan bids for 2024 exclude costs for ESRD

enrollees. These data were furnished by the Office of the Actuary.

14

Table I-3. Monthly Actuarial Value of Medicare Deductible and Coinsurance for 2023 and

2024

2023

2024

Change

2024 non-ESRD

Part A Benefits

$38.18

$36.62

-4.1%

$35.36

Part B Benefits

1

154.95

161.71

4.4

154.36

Total Medicare

193.13

198.33

2.7

189.72

1

Includes the amounts for outpatient psychiatric charges.

Medical Savings Account (MSA) Plans. The maximum deductible for MSA plans for 2024 is

$16,000.

15

Attachment II. Key Assumptions and Financial Information

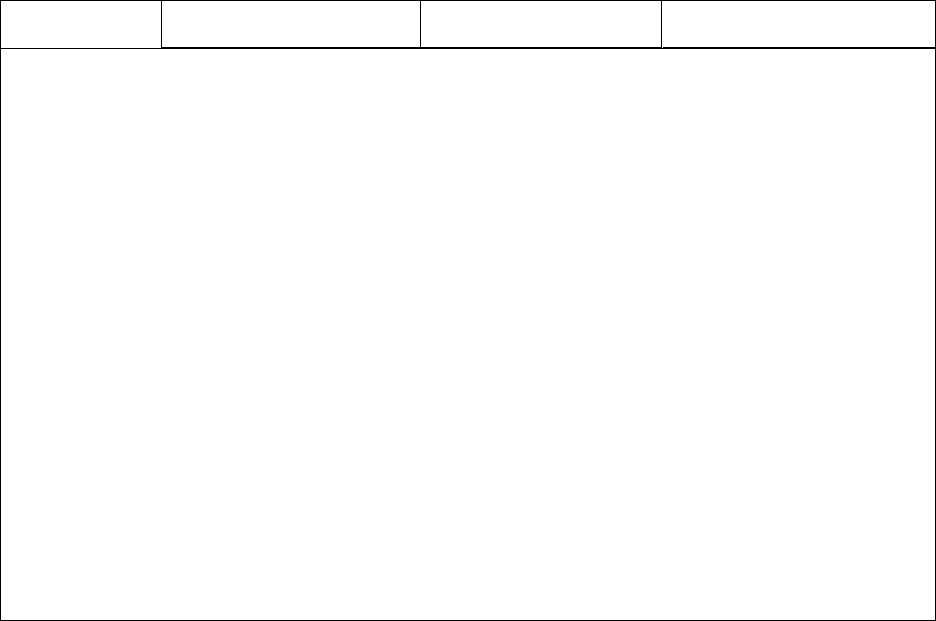

The USPCCs are the basis for the National Per Capita MA Growth Percentage. Below is a table

that compares last year’s estimates of USPCCs with current estimates for 2003 to 2025. In

addition, this table shows the current projections of the USPCCs through 2026. We are also

providing a set of tables that summarize many of the key Medicare assumptions used in the

calculation of the USPCCs. Most of the tables include information for the years 2003 through

2026.

Most of the tables in this attachment present combined aged and disabled non-ESRD data. The

ESRD information presented is for the combined aged-ESRD, disabled-ESRD, and ESRD only.

All of the information provided in this attachment applies to the Medicare Part A and Part B

programs. Caution should be employed in the use of this information. It is based upon

nationwide averages, and local conditions can differ substantially from conditions nationwide.

None of the data presented here pertain to the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit.

Table II-1. Comparison of Current & Previous Estimates of the Total USPCC – Non-ESRD

Part A

Part B

Part A + Part B

Calendar

year

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Ratio

2003

$296.18

$296.18

$247.66

$247.66

$543.84

$543.84

1.000

2004

314.08

314.08

271.06

271.06

585.14

585.14

1.000

2005

334.83

334.83

292.86

292.86

627.69

627.69

1.000

2006

345.30

345.30

313.70

313.70

659.00

659.00

1.000

2007

355.44

355.44

330.68

330.68

686.12

686.12

1.000

2008

371.90

371.90

351.04

351.04

722.94

722.94

1.000

2009

383.91

383.91

367.49

367.35

751.40

751.26

1.000

2010

383.93

383.93

376.34

376.12

760.27

760.05

1.000

2011

387.73

387.73

385.30

385.12

773.03

772.85

1.000

2012

377.37

377.37

391.93

391.76

769.30

769.13

1.000

2013

380.03

380.03

398.72

398.54

778.75

778.57

1.000

2014

370.23

370.23

418.36

418.18

788.59

788.41

1.000

2015

373.86

373.99

435.00

434.95

808.86

808.94

1.000

2016

377.62

377.61

444.28

444.14

821.90

821.75

1.000

2017

383.09

382.91

459.19

459.08

842.28

841.99

1.000

2018

388.12

388.06

489.65

489.43

877.77

877.49

1.000

2019

400.79

400.21

521.89

521.77

922.68

921.98

1.001

2020

403.90

402.19

522.48

522.62

926.38

924.81

1.002

16

Part A

Part B

Part A + Part B

Calendar

year

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Ratio

2021

409.38

412.79

569.14

573.53

978.52

986.32

0.992

2022

431.47

447.39

603.83

624.52

1,035.30

1,071.91

0.966

2023

459.23

469.56

658.56

668.36

1,117.79

1,137.92

0.982

2024

464.05

488.33

692.10

707.07

1,156.15

1,195.40

0.967

2025

480.98

509.50

729.01

744.57

1,209.99

1,254.07

0.965

2026

496.85

772.41

1,269.26

Table II-2. Comparison of Current &

Previous

Estimates of the FFS USPCC – Non-ESRD

Part A

Part B

Part A + Part B

Calendar

year

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Ratio

2010

$369.60

$371.20

$374.30

$373.99

$743.90

$745.19

0.998

2011

369.45

371.15

383.17

382.92

752.62

754.07

0.998

2012

355.15

356.97

390.70

390.45

745.85

747.42

0.998

2013

361.78

363.75

394.49

394.24

756.27

757.99

0.998

2014

362.07

364.24

409.16

408.89

771.23

773.13

0.998

2015

366.98

369.37

428.06

427.73

795.04

797.10

0.997

2016

369.00

371.57

433.62

433.36

802.62

804.93

0.997

2017

370.97

373.64

448.28

448.06

819.25

821.70

0.997

2018

374.54

377.84

474.15

473.79

848.69

851.63

0.997

2019

380.01

383.05

500.82

500.77

880.83

883.82

0.997

2020

370.93

372.68

473.65

473.99

844.58

846.67

0.998

2021

384.05

388.34

550.73

546.76

934.78

935.10

1.000

2022

398.10

424.46

573.64

598.85

971.74

1,023.31

0.950

2023

428.63

448.03

629.07

630.60

1,057.70

1,078.63

0.981

2024

440.70

465.39

664.40

666.68

1,105.10

1,132.07

0.976

2025

451.09

484.86

698.89

701.28

1,149.98

1,186.14

0.970

2026

459.88

739.42

1,199.30

Table II-3. Comparison of Current & Previous Estimates of the ESRD Dialysis-only FFS

USPCC

Part A

Part B

Part A + Part B

Calendar

year

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Ratio

2010

$2,952.75

$2,952.75

$3,881.39

$3,881.39

$6,834.14

$6,834.14

1.000

17

Part A

Part B

Part A + Part B

Calendar

year

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate

Ratio

2011

2,862.38

2,862.38

3,908.01

3,908.01

6,770.39

6,770.39

1.000

2012

2,774.49

2,774.49

3,944.59

3,944.59

6,719.08

6,719.08

1.000

2013

2,794.19

2,794.19

4,088.66

4,088.66

6,882.85

6,882.85

1.000

2014

2,784.52

2,784.52

4,115.70

4,115.70

6,900.22

6,900.22

1.000

2015

2,775.84

2,775.84

4,060.87

4,060.87

6,836.71

6,836.71

1.000

2016

2,895.91

2,895.91

4,081.27

4,081.27

6,977.18

6,977.18

1.000

2017

2,883.27

2,883.27

4,102.66

4,102.66

6,985.93

6,985.93

1.000

2018

2,952.21

2,952.21

4,526.09

4,526.09

7,478.30

7,478.30

1.000

2019

3,040.74

3,040.74

4,614.18

4,614.18

7,654.92

7,654.92

1.000

2020

3,082.55

3,082.55

4,542.51

4,542.51

7,625.06

7,625.06

1.000

2021

3,295.54

3,264.12

4,786.27

5,025.52

8,081.81

8,289.64

0.975

2022

3,395.47

3,646.65

4,863.56

5,279.76

8,259.03

8,926.41

0.925

2023

3,632.99

3,890.68

5,296.62

5,442.01

8,929.61

9,332.69

0.957

2024

3,835.56

4,057.82

5,709.41

5,648.71

9,544.97

9,706.53

0.983

2025

4,084.94

4,242.66

6,778.51

6,426.56

10,863.45

10,669.22

1.018

2026

4,347.69

7,309.00

11,656.69

Table II-4. Basis for ESRD Dialysis-only FFS USPCC Trend

Part A

Part B

Part A & Part B

Calendar

year

All ESRD

cumulative

FFS trend

Adjustment

factor for

dialysis-

only

Adjusted

dialysis-only

cumulative

trend

All ESRD

cumulative

FFS trend

Adjustment

factor for

dialysis-only

Adjusted

dialysis-only

cumulative

trend

All ESRD

cumulative

FFS trend

Adjustment

factor for

dialysis-only

Adjusted

dialysis-only

cumulative

trend

2022 1.02556 1.00465 1.03032 1.01381 1.00230 1.01615 1.01860 1.00327 1.02193

2023 1.09223 1.00931 1.10240 1.10155 1.00461 1.10663 1.09775 1.00652 1.10490

2024 1.14780 1.01400 1.16386 1.18467 1.00693 1.19287 1.16963 1.00976 1.18104

2025 1.21677 1.01871 1.23954 1.40326 1.00925 1.41624 1.32722 1.01278 1.34419

2026 1.28905 1.02344 1.31926 1.50961 1.01157 1.52708 1.41967 1.01597 1.44234

18

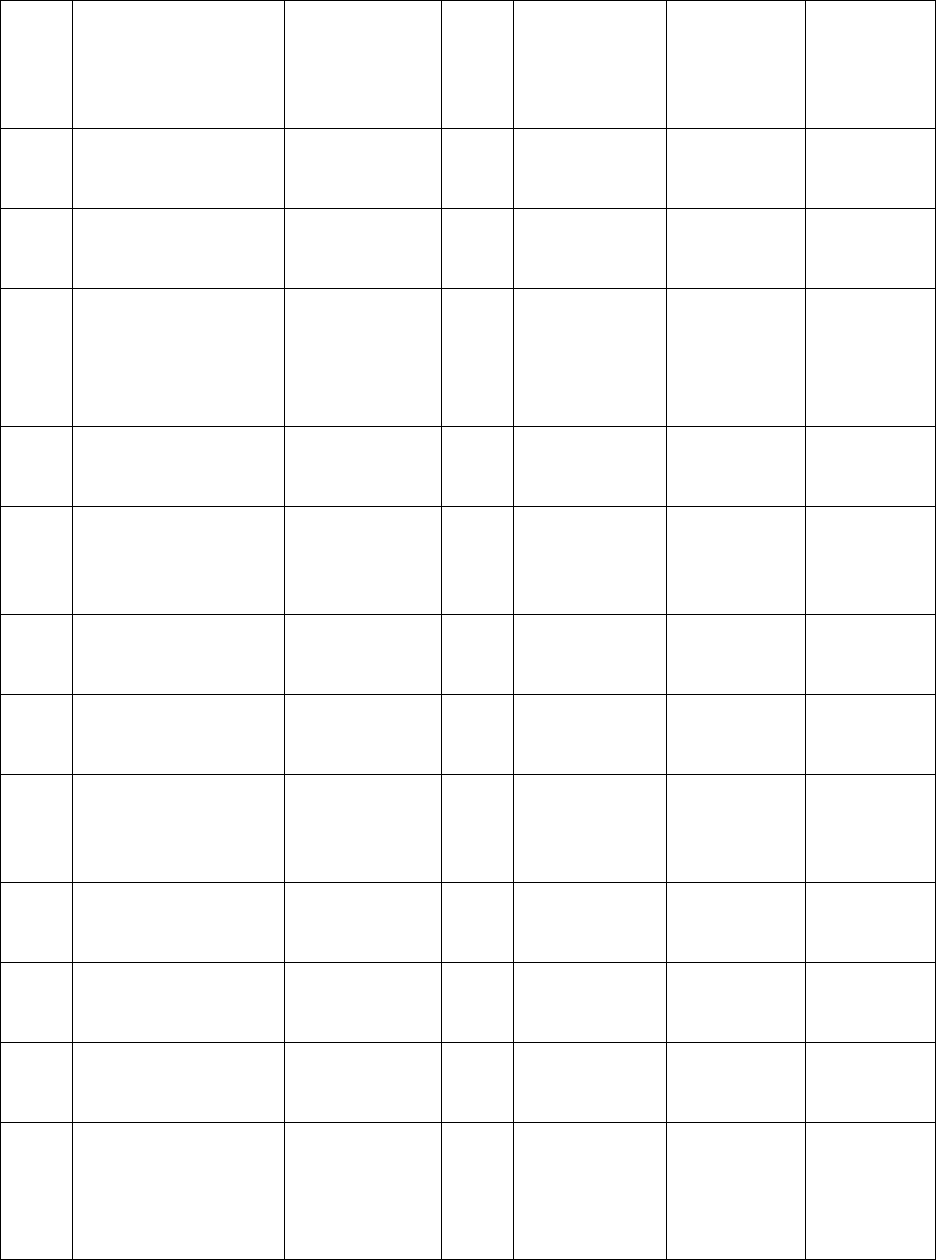

Table II-5. Summary of Key Projections

Part A

1

Year

Calendar year

CPI percent change

FY inpatient

PPS update factor

FY Part A total reimbursement

(incurred)

2003 1.4% 3.0%

3.5%

2004 2.1 3.4

8.4

2005 2.7 3.3

8.8

2006 4.1 3.7

5.9

2007 3.3 3.4

5.7

2008 2.3 2.7

7.6

2009 5.8 2.7

6.7

2010 0.0 1.9

3.0

2011 0.0 −0.6

4.5

2012 3.6 −0.1

0.4

2013 1.7 2.8

4.7

2014 1.5 0.9

0.6

2015 1.7 1.4

3.2

2016 0.0 0.9

4.3

2017 0.3 0.2

4.0

2018 2.0 1.8

4.0

2019 2.8 1.9

5.5

2020 1.6 3.1

3.2

2021 1.3

2.9

4.8

2022 5.9

2.5

4.7

2023 8.7

4.3

8.1

2024 3.3

2.8

5.3

2025 1.4

3.1

6.8

2026 2.1 2.9

7.3

19

Part B

2

Physician fee schedule

Calendar year Fees

3

Residual

4

Outpatient hospital

ESRD dialysis update

factor

5

Total

2003

1.4%

4.5%

4.4%

6.8%

2004

3.8

5.9

11.1

9.8

2005

2.1

3.2

10.8

7.0

2006

0.2

4.6

5.1

6.1

2007

-1.4

3.5

8.2

4.3

2008

-0.3

4.0

6.3

4.8

2009

1.4

2.3

5.4

3.9

2010

2.3

2.1

6.6

2.4

2011

0.8

2.3

7.1

2.5%

2.3

2012

-1.2

0.8

7.2

2.1

1.7

2013

-0.1

0.2

7.2

2.3

0.8

2014

0.4

0.6

12.6

2.8

3.4

2015

-0.3

-0.3

7.4

0.0

2.7

2016

-0.4

-0.3

5.2

0.15

1.9

2017

0.1

1.1

7.4

0.55

2.8

2018

0.5

1.1

8.4

0.3

5.7

2019

1.2

2.8

4.9

1.3

5.8

2020

0.2

-11.5

-6.0

1.7

-1.3

2021

4.8

13.1

20.0

1.6

8.7

2022

-1.1

4.0

6.5

1.9

4.9

2023

-0.5

3.4

15.1

3.0

7.4

2024

-1.7

3.5

9.1

1.6

4.8

2025

-1.9

3.0

8.3

2.3

5.6

2026

0.4

2.6

8.3

2.1

5.8

1

Percent change over prior year.

2

Percent change in charges per aged Part B enrollee.

3

Reflects the physician update and legislation affecting physician services—for example, the addition of new preventive services enacted in

1997, 2000, and 2010.

4

Residual factors are factors other than price, including volume of services, intensity of services, and age/sex changes.

5

The ESRD Prospective Payment System was implemented in 2011.

20

Part A

Part B

Calendar year

Aged

Disabled

Aged

Disabled

2003

34.437

5.961

33.038

5.215

2004

34.849

6.283

33.294

5.486

2005

35.257

6.610

33.621

5.776

2006

35.795

6.889

33.975

6.017

2007

36.447

7.167

34.465

6.245

2008

37.378

7.362

35.140

6.438

2009

38.257

7.574

35.832

6.664

2010

39.091

7.832

36.516

6.938

2011

39.950

8.171

37.247

7.254

2012

41.687

8.411

38.546

7.502

2013

43.087

8.629

39.779

7.732

2014

44.533

8.776

41.063

7.894

2015

45.911

8.853

42.311

7.977

2016

47.370

8.862

43.623

7.990

2017

48.893

8.940

44.944

8.007

2018

50.457

8.696

46.310

7.862

2019

52.110

8.531

47.765

7.735

2020

53.684

8.319

49.225

7.573

2021

55.041

8.054

50.513

7.359

2022

56.468

7.703

51.923

7.072

2023

58.030

7.384

53.481

6.785

2024

59.651

7.160

55.023

6.586

2025

61.276

7.093

56.595

6.532

2026

62.914

7.098

58.163

6.537

Non-ESRD Total

Table II-6. Medicare Enrollment Projections (In millions)

Non-ESRD Fee-for-Service

Part A

Part B

Calendar year Aged Disabled Aged Disabled

2003

29.593

5.628

28.097

4.875

2004

29.946 5.931 28.300 5.128

2005

30.014 6.178 28.287 5.339

2006

29.362 6.149 27.459 5.270

2007

28.838 6.225 26.782 5.297

2008

28.613 6.241 26.301 5.311

2009

28.563 6.288 26.071 5.374

2010

28.903 6.455 26.261 5.556

2011

29.210 6.659 26.440 5.736

2012

29.960 6.693 26.744 5.779

2013

30.330 6.691 26.948 5.790

2014

30.603 6.618 27.060 5.732

2015

30.947 6.488 27.274 5.609

2016

31.629 6.378 27.814 5.503

2017

31.916 6.299 27.882 5.361

2018

32.168 5.867 27.926 5.028

2019

32.456 5.467 28.017 4.666

2020

32.221 4.953 27.666 4.202

2021

31.438 4.409 26.816 3.711

21

Part A

Part B

Calendar year

Aged

Disabled

Aged

Disabled

2022

30.802 3.856 26.163 3.224

2023

30.410 3.205 25.703 2.581

2024

30.504 2.652 25.739 2.066

2025

30.941 2.434 26.129 1.864

2026

31.365 2.252 26.482 1.681

ESRD

ESRD - Total

ESRD - Fee-for-Service

Calendar year

Total Part A

Total Part B

Total Part A

Total Part B

2003

0.340

0.331

0.319

0.309

2004

0.353

0.342

0.332

0.321

2005

0.366

0.355

0.344

0.332

2006

0.382

0.370

0.353

0.340

2007

0.396

0.383

0.361

0.347

2008

0.411

0.397

0.367

0.353

2009

0.426

0.412

0.374

0.360

2010

0.442

0.428

0.388

0.373

2011

0.429

0.416

0.371

0.358

2012

0.441

0.429

0.379

0.366

2013

0.454

0.441

0.385

0.372

2014

0.469

0.456

0.390

0.377

2015

0.482

0.468

0.393

0.379

2016

0.496

0.481

0.400

0.384

2017

0.511

0.495

0.404

0.386

2018

0.524

0.507

0.405

0.387

2019

0.537

0.519

0.406

0.387

2020

0.540

0.522

0.396

0.377

2021

0.527

0.511

0.325

0.308

2022

0.509

0.495

0.272

0.258

2023

0.510

0.499

0.245

0.232

2024

0.520

0.508

0.236

0.223

2025

0.531

0.519

0.236

0.223

2026

0.543

0.531

0.237

0.223

22

Table II-7. Part A Projections for non-ESRD (Aged+Disabled)*

Calendar

year

Inpatient

hospital

Home health

agency SNF Managed care

Hospice: Total

re

imbursement

(in millions)

2003

2,594.78

370.63

124.28

457.87

5,733

2004

2,714.57

413.44

133.89

500.73

6,832

2005

2,818.21

450.54

140.87

602.29

8,016

2006

2,755.32

475.07

141.30

766.75

9,368

2007

2,696.33

504.24

143.72

916.90

10,518

2008

2,682.50

536.68

151.00

1,088.37

11,404

2009

2,637.34

551.67

153.86

1,260.14

12,274

2010

2,612.51

571.74

155.18

1,264.21

13,126

2011

2,570.82

623.31

138.31

1,314.41

13,897

2012

2,473.46

541.69

130.82

1,376.07

15,068

2013

2,468.49

540.47

128.47

1,416.56

15,263

2014

2,406.24

534.37

123.89

1,372.06

15,346

2015

2,388.54

530.99

126.08

1,435.16

16,159

2016

2,405.32

504.84

121.44

1,495.94

17,128

2017

2,381.77

484.69

117.35

1,609.39

18,228

2018

2,352.67

465.63

113.87

1,721.35

19,570

2019

2,314.56

444.32

108.47

1,938.76

21,174

2020

2,137.02

450.75

95.42

2,160.64

22,319

2021

2,117.54

421.03

93.28

2,277.75

23,034

2022

2,066.30

440.14

88.44

2,579.80

24,195

2023

2,146.67

417.69

94.63

2,848.53

26,017

2024

2,141.39

403.73

95.65

2,924.58

27,867

2025

2,122.61

434.96

102.09

3,108.74

30,079

2026

2,110.05

449.31

108.55

3,290.82

32,605

*Average reimbursement per enrollee on an incurred basis.

Table II-8. Part B Projections for non-ESRD (Aged+Disabled)*

Calendar year

Physician fee schedule Outpatient hospital Durable medical equipment

2003

$1,226.51

$364.77 $196.96

2004

1,344.01

418.85

195.61

2005

1,397.43

477.65

196.83

2006

1,396.40

497.47

197.78

2007

1,368.35

526.92

195.68

2008

1,367.83

555.09

200.92

2009

1,386.03

587.61

183.61

2010

1,429.74

623.13

183.76

2011

1,459.64

662.97

175.84

2012

1,412.72

697.86

173.70

2013

1,369.64

735.35

152.53

2014

1,351.32

823.34

128.57

2015

1,336.26

876.01

132.77

2016

1,313.75

911.03

120.73

2017

1,293.54

952.81

112.30

2018

1,285.36

1,000.20

127.05

2019

1,300.14

1,018.61

129.06

2020

1,111.11

914.01

123.59

23

2021

1,251.85

1,031.58

121.33

2022

1,208.99

1,014.01

125.84

2023

1,171.90

1,134.23

131.99

2024

1,149.61

1,190.45

133.58

2025

1,139.05

1,266.88

138.33

2026

1,147.58

1,346.13

143.96

Calendar

year

Carrier lab

24

Physician

administered drugs

Other carrier

Intermediary lab

2003

$73.73

$182.58

$147.21

$75.18

2004

78.48

195.20

158.78

2005

80.47

82.71

178.77

184.02

84.16

2006

85.59

185.41

175.66

84.51

2007

90.65

186.97

176.55

84.38

2008

94.50

184.43

182.19

85.78

2009

101.60

196.19

178.46

79.19

2010

103.81

196.41

178.67

80.23

2011

103.85

209.50

179.44

83.31

2012

111.73

209.34

185.17

84.64

2013

111.79

216.91

177.08

81.74

2014

117.60

224.56

173.55

55.45

2015

113.99

252.11

174.94

55.26

2016

100.91

271.45

172.90

56.21

2017

100.65

280.51

177.43

54.99

2018

107.28

304.36

176.15

52.94

2019

108.73

329.41

174.14

50.31

2020

109.18

325.03

166.87

51.77

2021

122.82

340.52

165.36

56.25

2022

112.53

359.41

178.83

52.95

2023

116.31

368.95

184.37

52.89

2024

118.37

389.08

184.22

52.28

2025

128.70

410.19

187.50

54.52

2026

132.58

432.42

191.43

55.03

*Average reimbursement per enrollee on an incurred basis.

25

Calendar year

Other intermediary

Home health agency

Managed care

2003

$113.99

$136.75

$421.40

2004

119.58

156.45

471.37

2005

139.78

179.44

560.31

2006

142.09

202.88

769.94

2007

151.16

232.33

931.18

2008

158.20

252.43

1,104.26

2009

187.44

282.09

1,203.79

2010

193.08

283.25

1,221.29

2011

198.15

254.42

1,276.29

2012

205.08

239.36

1,368.13

2013

194.43

234.07

1,497.49

2014

200.51

227.73

1,703.30

2015

210.37

224.84

1,829.20

2016

214.14

219.09

1,938.69

2017

220.58

208.93

2,096.95

2018

228.23

206.47

2,376.35

2019

236.12

201.48

2,704.42

2020

208.83

187.27

3,062.48

2021

219.92

182.59

3,327.89

2022

214.19

169.26

3,800.44

2023

212.86

177.44

4,341.49

2024

214.10

175.38

4,687.26

2025

221.29

182.19

5,007.97

2026

228.98

194.55

5,384.17

* Average reimbursement per enrollee on an incurred basis.

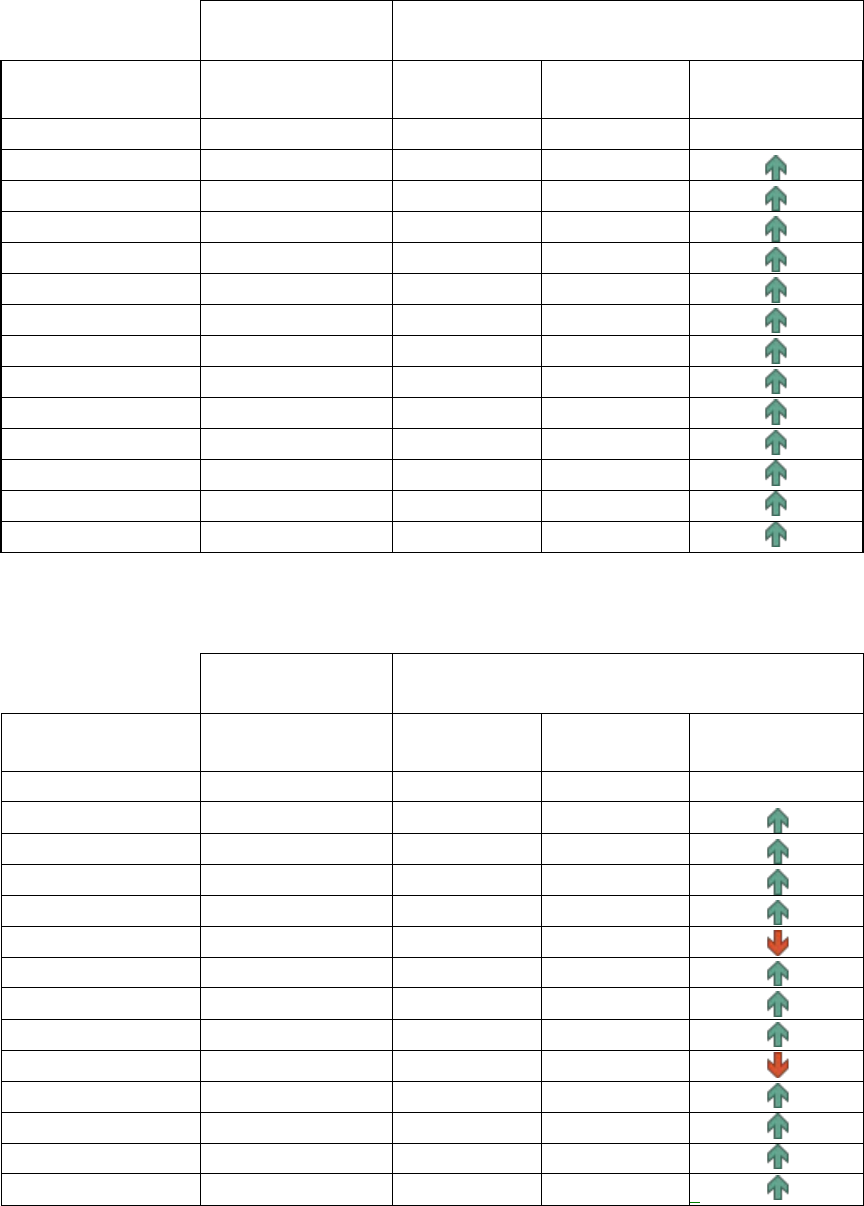

Table II-9. 2024 Projections by Service Category for non-ESRD (Aged+Disabled)*

Service type

Current

estimate

Last year’s

estimate Ratio

Part A

Inpatient hospital

$2,141.39

$2,303.60

0.930

SNF

403.73

447.80

0.902

Home health agency

95.65

126.49

0.756

Managed care

2,924.58

2,978.53

0.982

Part B

Physician fee schedule

1,149.61

1,170.57

0.982

Outpatient hospital

1,190.45

1,232.65

0.966

Durable medical equipment

133.58

126.40

1.057

Carrier lab

118.37

107.45

1.102

Physician Administered Drugs

389.08

420.58

0.925

Other carrier

184.22

163.46

1.127

Intermediary lab

52.28

44.36

1.179

Other intermediary

214.10

245.56

0.872

Home health agency

175.38

245.69

0.714

Managed care

4,687.26

4,716.27

0.994

* Average reimbursement per enrollee on an incurred basis.

26

Table II-10. Claims Processing Costs as a Fraction of Benefits

Calendar

year

FFS Part A

FFS Part B

Total Part A

Total Part B

2003

0.001849

0.011194

0.001849

0.011194

2004

0.001676

0.010542

0.001676

0.010542

2005

0.001515

0.009540

0.001515

0.009540

2006

0.001245

0.007126

0.001245

0.007126

2007

0.000968

0.006067

0.000968

0.006067

2008

0.000944

0.006414

0.000944

0.006414

2009

0.000844

0.005455

0.000844

0.005455

2010

0.000773

0.005055

0.000773

0.005055

2011

0.000749

0.004396

0.000749

0.004396

2012

0.001008

0.003288

0.001008

0.003288

2013

0.000994

0.002846

0.000994

0.002846

2014

0.001003

0.002884

0.001003

0.002884

2015

0.000952

0.002730

0.000952

0.002730

2016

0.000852

0.002348

0.000852

0.002348

2017

0.000833

0.002111

0.000833

0.002111

2018

0.000836

0.001953

0.000836

0.001953

2019

0.000699

0.001644

0.000699

0.001644

2020

0.000625

0.001536

0.000625

0.001536

2021

0.001038

0.002708

0.000600

0.001399

2022

0.001094

0.002801

0.000582

0.001310

2023

0.001094

0.002801

0.000582

0.001310

2024

0.001094

0.002801

0.000582

0.001310

2025

0.001094

0.002801

0.000582

0.001310

2026

0.001094

0.002801

0.000582

0.001310

27

Approximate Calculation of the USPCC, the National MA Growth Percentage for

Combined (Aged+Disabled) Beneficiaries, and the FFS USPCC (Aged+Disabled)

The following procedure will approximate the actual calculation of the USPCCs from the

underlying assumptions for the contract year for both Part A and Part B.

Part A: The Part A USPCC can be approximated by using the assumptions in the tables titled

“Part A Projections for non-ESRD (Aged+Disabled)” and “Claims Processing Costs as a

Fraction of Benefits.” Information in the “Part A Projections” table is presented on a calendar

year per capita basis. First, add the per capita amounts over all types of providers (excluding

hospice). Next, multiply this amount by 1 plus the loading factor for administrative expenses

from the “Claims Processing Costs” table. Then, divide by 12 to put this amount on a monthly

basis.

Part B: The Part B USPCC can be approximated by using the assumptions in the tables titled

“Part B Projections for non-ESRD (Aged+Disabled)” and “Claims Processing Costs as a

Fraction of Benefits.” Information in the “Part B Projections” table is presented on a calendar

year per capita basis. First, add the per capita amounts over all types of providers. Next, multiply

by 1 plus the loading factor for administrative expenses from the “Claims Processing Costs”

table and then divide by 12 to put this amount on a monthly basis.

The National Per Capita MA Growth Percentage: The National Per Capita MA Growth

Percentage for 2024 (before adjusting for prior years’ over/under estimates) is calculated by

adding the USPCCs for Part A and Part B for 2024 and then dividing by the sum of the current

estimates of the USPCCs for Part A and Part B for 2023.

The FFS USPCC: The tables used to calculate the total USPCC can also be used to approximate

the calculation of the FFS USPCC. The per capita data presented by type of provider in the

projections tables for both Part A and Part B are based on total enrollment. To approximate the

FFS USPCCs, first add the corresponding provider types under Part A and Part B separately. For

the FFS calculations, do not include the managed care provider type. Next, rebase the sum of the

per capita amounts for FFS enrollees, i.e., multiply the sum by total enrollees and divide by FFS

enrollees. (The enrollment tables in this attachment now also include FFS enrollment.) Then,

multiply by 1 plus the loading factor for administrative expenses and divide by 12. The result

will only be approximate because there is an additional adjustment to the FFS data which

accounts for cost plan data which comes through the FFS data system. This cost plan data is in

the total per capita amounts by type of provider, but it is removed for the FFS calculations.

28

Attachment III. Responses to Public Comments on Part C Payment Policy

Section A. General Comments

Comment: CMS received a large number of comments in response to the CY 2024 Advance

Notice, with many supporting the direction of the proposals in the Advance Notice and others

expressing concerns about the impacts of the proposed updates. Commenters who supported the

proposals in the Advance Notice believed that the methods taken to update factors, including the

capitation rates, were sound and that the adjustments, such as those to capitation rates, were

much needed to ensure payment accuracy and preserve the financial integrity of the Medicare

Trust Fund. Commenters also cited overpayments to MA organizations and concerns that

wasteful spending is weakening the Medicare program, placing extra pressure on the Medicare

Trust Fund, and being subsidized by all Medicare beneficiaries via higher Part B premiums. A

number of commenters cited MedPAC’s findings that excess payments to MA organizations will

exceed $27 billion in 2023 and they estimate aggregate excess payments to MA organizations

have totaled nearly $124 billion from 2007 to 2023. One commenter stated that this year’s

projected revenue increase of 1% was an improvement in CMS’ management of the MA

program compared to recent years, such as the projected increase of 8.5% for payment in 2023.

Commenters also emphasized that discretionary coding and perceived ‘gaming’ of codes is a key

part of driving excess payments, and applauded efforts to make the model more accurate and less

susceptible to discretionary coding. Another commenter noted that, while changes to the risk

adjustment model in the proposal and previous policies impacting quality bonuses would tend to

reduce payments to MA organizations, these decreases would be more than offset by an increase

in MA benchmarks driven by increases in diagnostic coding by plans. It was also stated that

though many MA organizations and associations state that if the MA risk score trend is excluded

from the year over year revenue calculation projected payment would decrease, there is no

reason to exclude the risk score growth from the estimate of the year-over-year percentage

change in payment to have an accurate estimate.

The commenters who did not support the proposed changes saw the net effect of the proposals as

cuts to the MA program and urged CMS to maintain stability in the program and not implement

the proposed updates. Many commenters submitted a wide array of suggestions regarding

proposals in the Advance Notice, including the medical education adjustment to the growth

percentages and the updated risk adjustment model. Several commenters stated that the

combined effect of the updates to the growth percentages and the risk adjustment model, as well

as the impact of Star Ratings, would materially affect benchmarks and result in significant

payment reductions. Some commenters stated that the MA risk score trend is not actually part of

the MA payment methodology, and that if the risk score trend were not taken into account the

year-to-year change in payment would be a negative 2.27%, and not a positive 1.03%. These

commenters asserted that a variety of impacts would occur if CMS finalized the proposed

changes including that these proposals would disrupt care, place the health of sicker, lower-

29

income enrollees at risk, and result in increased costs and reduced benefits for MA enrollees.

These commenters highlighted the potential for reduced funding for supplemental benefits and

claimed that these policies would result in reductions in the coverage of dental, hearing, vision,

transportation, and cost sharing for drugs, as well as in hindering the development of complex,

innovative solutions to providing care to Medicare beneficiaries. Further, some commenters

stated that provision of care would suffer and value-based models would also suffer and result in

deteriorating health outcomes.

Response: CMS thanks commenters for their thoughts and input regarding payments made under

the MA program. CMS has a duty to be a steward of the Medicare program. Protecting and

strengthening Medicare for the 65 million Americans who have it now, and all the beneficiaries

in the future, is a key priority for CMS.

Core to this mission is to maintain stability for Medicare beneficiaries in both Medicare FFS and

MA. The policies finalized for CY 2024 are projected to increase average payments to MA

organizations by 3.32% in CY 2024, which will provide continued stability to the MA market

and MA beneficiaries. The policies we are finalizing are commonsense, clinically-based

technical updates that are crucial to ensuring that payments to MA organizations are up to date

and reflect current diagnostic and expenditure trends. These updates ensure accurate payment to

MA organizations and prevent wasteful Medicare spending. These policies were proposed and

finalized using careful analyses, iterative clinical input, and with CMS’ strategic pillars,

especially our commitment to health equity, top of mind.

We respectfully disagree with some commenters’ claims that this reasonable update to payments

in MA is actually a payment cut that will result in increased costs or fewer benefits for

beneficiaries. These comments disregard the payment impact of increases in plan risk scores,

which is an essential element to understanding the full revenue picture for MA organizations.

Well-established historical trend data show that MA organizations continue to increase the

diagnostic codes they submit to CMS for payment, even when models are updated. We have

included assumptions for a reduced MA risk score trend due to the updated model. Moreover, we

note that there have been prior years when the overall expected revenue change was lower than

the 3.32% change projected in this Rate Announcement, and enrollment in MA plans and the

extra payments that MA plans receive from CMS, called rebates, to provide supplemental

benefits that are above and beyond those available in Medicare FFS, consistently increased over

the years, including the years of lower growth in payments. In fact, over the past decade MA has

become a very robust market, where plans compete for enrollment in large part by offering zero

premium plans and generous supplemental benefits. In fact, rebates have more than doubled in

the past five years and rose 20% from 2022 to 2023. The competitiveness of the MA market has

also resulted in beneficiaries having access to on average approximately 61 plans and roughly

60% of enrollees enrolled in zero premium plans.

30

The updates proposed by CMS in the CY 2024 Advance Notice are technical, data-driven, and

clinically-based updates that improve the accuracy of payments to MA organizations, as required

under the statute governing the MA program. We expect MA organizations that are committed to

their MA business to have strong business plans, long term financial strength, and a business

trajectory beyond a single year.

Though plans will have different impacts for the policies finalized, the robust strength and

competitiveness of the market and high level of choice ensure that the 3.32% nationally averaged

update will result in maintained stability.

Section B. Estimates of the MA and FFS Growth Percentages for 2024

Technical Update to USPCC baseline regarding MA-related Medical Education Expenses

Comment: In the CY 2024 Advance Notice, we proposed a technical change to remove medical

education costs (IME and DGME) paid to hospitals by CMS associated with services furnished

to MA enrollees from the historical and projected expenditures supporting the non-ESRD FFS

USPCCs beginning with the CY 2024 ratebook. Several commenters expressed support for the

technical update to remove medical education payments paid by CMS to hospitals associated

with services furnished to MA enrollees from the non-ESRD FFS USPCC estimates, in order to

make payments to MA organizations more appropriate and accurate.

A few commenters expressed appreciation for CMS’ ongoing efforts regarding data evaluations

and improvements regarding the development of per capita FFS costs, and for the transparency

provided by CMS concerning these efforts. One of these commenters encouraged CMS to

continue to take steps to improve the level of transparency related to the methodologies and

analysis supporting the development of the USPCCs and county benchmarks, such as providing

more details in the Advance Notice on how adjustment factors are calculated including data

source/scope and providing further explanation of changes to methodologies.

Response: We appreciate the support and feedback provided by the commenters.

Comment: A large number of commenters expressed concern regarding the full implementation

of the technical update to the USPCC baseline at one time, and recommended that the change

instead be phased in gradually over multiple years to minimize disruption to premiums and

benefits. Several of these commenters noted that CMS has previously phased in benchmark

changes, citing as examples the statutory phase-in of the Affordable Care Act benchmark

changes and the incremental IME phase-out per section 1853(k)(4)(B)(ii) of the Act.

A couple of commenters requested that the technical update be delayed and not finalized for CY

2024. An additional couple of commenters recommended that CMS not proceed with the

proposed technical update to the USPCCs for CY 2024, requesting instead that CMS provide

more information about the methodology for identifying medical education payments and the

31

adjustments to the county benchmarks and USPCCs. One of these commenters believed there

was insufficient time for stakeholders to analyze the potential impacts of the technical proposal.

Response: We appreciate the commenters’ suggestions to phase in or delay the technical update

to the data used for the USPCC baseline. The Secretary has directed the CMS Office of the

Actuary to phase in the technical update to the data used to develop the USPCCs over a 3-year

period beginning with 33% of this adjustment to the medical education costs applied to the

USPCCs in 2024. We expect 67% of the 2025 medical education adjustment to be applied in

2025 and 100% of the 2026 medical education adjustment to be applied in 2026.

Comment: Several commenters noted that there has already been an adjustment to remove

medical education costs from the county-level benchmarks in prior years. Many commenters

requested clarification regarding how the medical education costs being removed from the non-

ESRD FFS growth rate for the technical change is different than the medical education costs

removed from county-level benchmarks as an adjustment to the Average Geographic Adjustment

(AGA). A few of these commenters inquired whether there is any overlap between the amounts

being removed from the USPCC and those being removed at the county level.

Response: The adjustments to the USPCC and AGA pertain to two different groups of Medicare

beneficiaries: the technical update to the non-ESRD FFS USPCC pertains to excluding IME and

DGME costs associated with MA enrollees (paid directly by CMS to hospitals), whereas the

county level adjustment to the AGA pertains to IME and DGME costs associated with FFS

beneficiaries (paid directly by CMS to hospitals) to determine MA capitation rates as required by

section 1853 of the Act. Historically, IME and DGME payments included in the non-ESRD FFS

USPCCs were sourced from historical inpatient cost reports and included amounts paid on behalf

of both FFS and MA enrollees. The cost reports are used as a source for the baseline projections

of the USPCCs since the data contains more detail of the various components of hospital

payments that are projected separately, including capital, bad debt, and ancillary pass through

payments. In contrast, the IME and DGME payments used to calculate the ratebook IME and

DGME carve-out factors applied to the AGAs were sourced from the FFS claims records and, as

such, the adjustment in the county FFS rate calculation has always been limited to the payments

for FFS admissions. The claim records, and not cost reports, are used in the ratebook medical

education exclusion because the claim records include the beneficiary’s county of residence.

Therefore, no corresponding adjustment is required to the IME phase-out and DGME carve-out

adjustments to the AGAs in the county ratebook calculation to remove costs associated with MA

enrollees. As stated on page 11 of the CY 2024 Advance Notice, the technical update has no

impact on the exclusion of medical education costs from the AGAs used to develop the ratebook.

Comment: A few commenters believed that the explanation of the technical change in the

Advance Notice was limited and did not fully explain how the change will affect cost

projections, why the technical change is being implemented at this time, how the impact was

determined, and the statutory basis for the technical change.

32

Many commenters requested more transparency and details regarding the technical update and