A Study of

Metro Nashville/Davidson

County Finances

Conducted for

Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce

and Greater Nashville REALTORS®

by Elliott Davis

Table of Contents

Executive Summary from Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce and the

Greater Nashville REALTORS®

Report Sections

Study Overview ............................................................................................... 3

Peer Cities Selection ....................................................................................... 4

Financial Position and Trends ......................................................................... 6

Financial Forecast ......................................................................................... 20

OPEB ............................................................................................................ 26

Tax and Fee Burden ..................................................................................... 31

Transit ........................................................................................................... 33

Affordable Housing ....................................................................................... 35

Technology Investment Opportunities and Challenges ................................ 37

Observations ................................................................................................. 41

Appendix A ........................................................................................................ 45

Appendix B ........................................................................................................ 46

1

Executive Summary

Prepared by the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce

and the Greater Nashville REALTORS®

The Boards of Directors of the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce and Greater Nashville

REALTORS® (collectively “the boards”) engaged Elliott Davis, an independent consultant

group, to conduct a study of the finances of Metro Nashville/Davidson County government. The

primary objective of the study was to provide information to the boards for their consideration in

shaping boards’ response to budgeting and financial decisions of Metro Nashville.

The study is based on an evaluation of publicly available financial information including

Nashville’s recent Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports (CAFRs) and annual budgets. This

study analyzed funding issues, identified trends in financial results and compared the city’s

overall financial condition to other peer cities.

The consultants approached this study by assisting with the following:

• Understanding historical financial information as reported in recently issued

Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports (CAFRs) of Nashville.

• Assessing the overall financial condition of Nashville based on information presented in

the CAFRs.

• Comparing certain historical information of Nashville to that of select peer cities.

• Forecasting general fund revenues and expenditures of Nashville based on historical

trends and the application of specific assumptions.

Study Components

Financial Position and Trends - Financial information as reported in Nashville’s CAFRs was

analyzed to highlight funding and expense issues, identify trends in financial results, and to

compare the City’s overall financial position to that of its peers.

Financial Forecast - The Study includes a forecast of general fund revenues and expenditures

of Nashville for a five-year period and presents several scenarios for potential increases in

revenue as required to fund certain investment initiatives and to achieve assumed fund balance

goals.

Tax and Fee Burden - The Study also includes an overview of taxes and fees incurred by

residents of Nashville with a comparison to that of the Peer Cities. To facilitate comparability,

various rates and assessments for the respective municipalities were applied to a representative

Nashville household having certain characteristics related to home prices, annual income and

spending, and utility consumption.

Other Areas - Finally, the Study considers three of the most significant challenges currently

faced by growing municipalities across the US: 1.) availability of affordable housing; 2.)

developing and maintaining an effective transit system; and 3.) navigating the opportunities and

risks presented by technology and automation.

Peer Cities - Six municipal governments were identified as “Peer Cities” of Nashville for the

purpose of comparing certain financial metrics including debt levels, the status or fund balance

and trends in revenues and expenses. The comparison also considered the implementation of

2

major initiatives such as those related to transit systems, affordable housing and the use of

technology to improve efficiency in government.

This executive summary was prepared by staff of the boards. The remainder of the report is the

original work of Elliott Davis.

3

Study Overview

The Study is based on the evaluation of certain publicly available financial information including

Nashville’s recent CAFR’s and annual budgets. We also evaluated planning studies and

committee reports available on Nashville’s website, as well as media accounts discussing

Nashville’s recent budgeting decisions and financial condition. In conducting the Study we did

not have access to Nashville’s finance team or other members of Nashville’s management. As a

result, we were not able to conduct interviews and inquiries with current City personnel for the

purpose of corroborating and adding context to our observations and recommendations.

Six municipal governments were identified as “Peer Cities” of Nashville for the purpose of

comparing certain financial metrics including debt levels, the status of fund balance, and trends

in revenues and expenses. The comparison also considered the implementation of major

initiatives such as those related to transit systems and affordable housing.

In evaluating Nashville’s financial position and performance trends, we analyzed elements of the

government-wide financial statements as reported in the CAFR’s of Nashville and the Peer Cities

for the fiscal years from 2009 through 2018. For purposes of comparability among municipalities,

we deemed the government-wide financial statements to be more effective than fund financial

statements as they alleviate the need to mix and match different fund structures and funding

approaches. In addition, government-wide financial statements largely reduce the effect of

transfers between funds, as they are limited to the less significant transactions occurring between

governmental and business-type activities. While Nashville’s 2019 CAFR became available to us

as the Study was being completed, it was only utilized for certain portions of the Study as the

2019 CAFR’s were not yet published for most of the Peer Cities. Therefore, analysis involving

the Peer Cities is limited to information obtained from CAFR’s issued for fiscal year 2018.

The Study included the development of a five-year financial forecast of Nashville’s general fund.

The objective of the forecast is to estimate the future trajectory of Nashville’s available fund

balance based on certain assumptions and historical trends in revenues and expenditures ranging

from five to ten years. Assumptions incorporated into the forecast include growth rates for major

revenue categories, and inflation factors for major costs such as healthcare benefits, capital

spending, and professional services. The forecast also presents several scenarios reflecting

potential increases in revenue as required to fund certain investment initiatives and to achieve

assumed fund balance goals.

An overview of taxes and fees incurred by residents of Nashville and the Peer Cities was

developed to illustrate a significant portion of the average household’s burden to fund operations

of state and local government. To facilitate comparability, various rates and assessments for the

respective municipalities were applied to a representative Nashville-household having certain

characteristics related to home price, annual income and spending, and utility consumption.

The Study also considers three of the most significant challenges currently faced by growing

municipalities across the US: 1.) availability of affordable housing; 2.) developing and maintaining

an effective transit system; and 3.) navigating the opportunities and risks presented by technology

and automation. This section includes initiatives being developed and implemented by several

US cities, and strategies for funding these initiatives.

The final section of the Study identifies best practices to enhance Nashville’s processes

surrounding financial operations and budgetary decision-making.

4

Peer Cities Selection

The Peer Cities that were selected for the Study were deemed to be similar to Nashville in terms

of current population, growth rate, and organizational structure. The Boards initially identified nine

such municipalities, several of which also possessed certain characteristics considered desirable

by the Boards in terms of future objectives for Nashville. This list of cities included:

• Atlanta

• Charlotte

• Raleigh

• Austin

• Louisville

• Jacksonville

• Indianapolis

• Salt Lake City

• Denver

From the above list of nine cities, six were considered to be most beneficial for inclusion in the

analysis. The following criteria were applied to arrive at the final list:

• Having a similar population to Nashville as reported in the respective 2018 CAFR of each

city

• Being the dominant city in the area, making up most of the urban region

• Having a consolidated city/county government

• Being a state capital

• Being a growing city with a healthy economy

Based on the above criteria, the following six cities were selected with the major factors

weighing in favor of their selection as described below:

Charlotte - A growing city, dominant in its area with a similar population to Nashville

(859,035) and while not a consolidated city, sharing many services with its county.

Louisville - A consolidated city/county government with a similar population

(771,158) and status as the main city in the region, an expanding population, and

strong economic growth.

Jacksonville - Consolidated with Duval County, the city has a comparable

population (952,861) and a healthy economy.

Indianapolis - Another city with a consolidated government, it is also the state

capital, dominant in its region, and has a growing population (867,125).

Austin – As the state capital, the city dominates its immediate region and is growing

in population (963,797) and economic influence.

Denver - This is another consolidated city/county government that is a state capital

and is expanding both in terms of population (716,492) and economic growth.

Not selected were:

5

Raleigh - While this city is growing and is a state capital, it is much smaller than

Nashville (469,298) and makes up a much smaller part of the regional area as the

Cities of Durham, Cary and Chapel Hill exert major influence on the Research

Triangle area.

Atlanta - This city is also similar to Raleigh as a state capital but with a smaller

population (486,290) relative to the Nashville area.

Salt Lake City - This city is a state capital, but it is smaller in population (200,544)

and is not a consolidated city/county government.

Certain financial aspects of the selected cities were compared, including financial health as

measured by fund balance reserves, bond ratings, debt service requirements, OPEB costs, and

the level of taxes and fees imposed.

6

Financial Position and Trends

Debt and Fund Balance Metrics

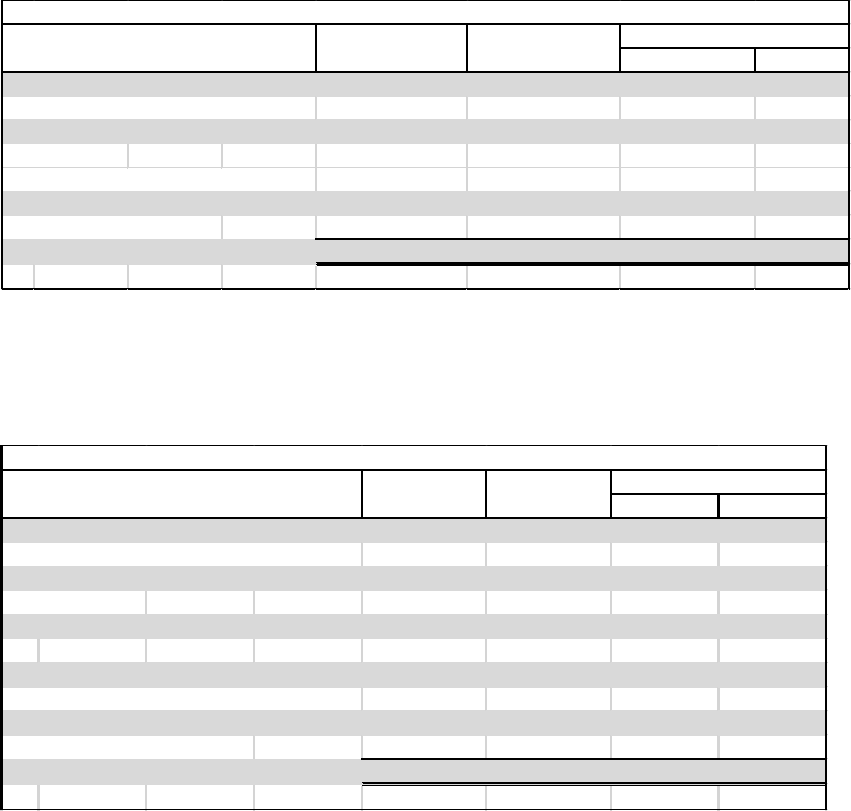

Figure 1 below presents metrics which highlight the overall financial position of Nashville in

comparison to the Peer Cities with an emphasis on the amount of governmental debt, the level of

unrestricted general fund reserves (fund balance), and the credit rating applied to its general

obligation bonds. While Nashville utilizes multiple funds, our consideration of unrestricted fund

balance in the table below focuses on the general fund only as it typically generates over 40% of

the City’s total revenues in any given fiscal year and reports the largest portion of its available

fund balance.

Sources of information for this comparison were drawn primarily from the 2018 CAFR’s, budget

documents, and other publicly available financial reports of the respective Peer Cities:

Austin Charlotte Denver Indianapolis Jacksonville Louisville

Population 692,587 963,797 875,318 716,492 867,125 952,861 771,158

Bond ratings

(Moody's, S&P)

Aa2, AA Aaa, AAA Aaa, AAA Aaa, AAA Aaa, AA+ A2, AA Aa1, AA+

Governmental

fund debt

$2.8

billion

$1.5

billion

$0.8

billion

$1.4

billion

$124

million

$2.2

billion

$0.5

billion

Governmental

fund debt per

capita

4,104$ 1,587$ 880$ 2,003$ 126$ 2,267$ 697$

Debt service ratio 10.0% 12.5% 16.8% 10.7% 12.9% 12.1% 9.5%

Combined debt

(Governmental

and Proprietary

funds)

$3.9

billion

$6.5

billion

$4.6

billion

$8.1

billion

$1.3

billion

$2.6

billion

$0.5

billion

Combined debt

per capita

5,644$ 6,761$ 5,293$ 11,328$ 1,455$ 2,689$ 732$

General fund -

unrestricted fund

balance

$75.8

million

$210.9

million

$120.4

million

$304.2

million

$188.6

million

$260.4

million

$101.8

million

General fund -

months of

expenditures in

fund balance

0.95 2.51 2.38 2.92 3.16 3.24 1.91

Debt and Fund Balance Metrics - Fig. 1

Metric

Nashville

Peer Cities

According to the 2018 CAFR, Nashville has governmental fund debt outstanding of $2.8 billion.

At $4,104 per capita, this represents a higher governmental debt per capita than the Peer Cities.

When both governmental and proprietary fund indebtedness are combined, Nashville compares

more favorably with its peers. This in part reflects major enterprise activities being undertaken in

the Peer Cities (e.g., Denver Airport). However, it also reflects the deferral of capital

improvements to Nashville’s water and sewer infrastructure.

7

Another significant metric for evaluating a government’s debt burden is the debt service ratio - the

percentage of governmental fund expenditures attributable to debt service. In Nashville’s case,

while a debt service ratio of 10% compares favorably with that of the Peer Cities, it also reflects

Nashville’s overall growth in non-debt service general fund expenditures.

In terms of financial credit ratings, Nashville has relatively strong ratings of Aa2 (Moody’s) and

AA (S&P) which may be attributed to a robust economy and a very modest property tax rate.

However, Nashville’s ratings are the lowest among the Peer Cities except for Jacksonville which

lags slightly behind Nashville with ratings of A2 (Moody’s) and AA (S&P). While a number of

factors can affect a government’s credit rating, Nashville’s lower ratings compared to its peers are

likely due in part to a significant long-term decrease in net position (see Figure 3 at page 13) and

a rapidly growing OPEB liability.

For the 2018 fiscal year Nashville reported an unrestricted balance in the general fund of

approximately $75.8 million. Unrestricted fund balance represents the portion of fund balance

that is spendable and has not been restricted by externally imposed requirements such as those

reflected in debt agreements or enabling legislation. Unrestricted fund balance is calculated by

taking the sum of the fund balance amounts reported in the financial statements as “committed”,

“assigned”, and “unassigned”.

As a result, it generally serves as a reserve to be used for any other legal purpose as required for

the continued operation of the government.

According to the Government Finance Officers Association (the GFOA): “It is essential that

governments maintain adequate levels of fund balance to mitigate current and future risks (e.g.,

revenue shortfalls and unanticipated expenditures) and to ensure stable tax rates.” The GFOA

recommends that at a minimum, a general purpose government should maintain in their general

fund an unrestricted fund balance of no less than two months of regular general fund operating

revenues or regular general fund operating expenditures. However, the GFOA stipulates that this

should only be considered a general “rule of thumb” and further recommends the following:

“The adequacy of unrestricted fund balance in the general fund should take into

account each government’s own unique circumstances. For example,

governments that may be vulnerable to natural disasters, more dependent on a

volatile revenue source, or potentially subject to cuts in state aid and/or federal

grants may need to maintain a higher level in the unrestricted fund

balance. Furthermore, a government’s particular situation often may require a

level of unrestricted fund balance in the general fund significantly in excess of this

recommended minimum level. In any case, such measures should be applied

within the context of long-term forecasting, thereby avoiding the risk of placing too

much emphasis upon the level of unrestricted fund balance in the general fund at

any one time.”

As reflected in Figure 1, as of the end of the 2018 fiscal year, Nashville maintained less than one

month of general fund expenditures in unrestricted fund balance. This is significantly less than

both the GFOA-recommended minimum of two months and the range of 1.91 months to 3.24

months for the Peer Cities. Figure 2 below presents a further comparison of months of

expenditures in unrestricted fund balance. In computing 10-year and 5-year averages, Nashville

trails all of the Peer Cities in the number of months of expenditures held as reserves in unrestricted

fund balance.

8

Government-wide Analysis

We also considered Nashville’s overall financial position and performance as indicated by its

government-wide financial statements, including a comparison of certain metrics to those of the

Peer Cities. The government-wide financial statements are designed to provide readers with a

broad overview of the Government's finances, in a manner similar to a private-sector business.

The two government-wide financial statements are, as follows:

The Statement of Net Position presents information on all of the Government's

assets, deferred outflows of resources, liabilities, and deferred inflows of resources,

with the difference reported as net position. In short, government’s net position

reflects the amount by which its assets (or financial resources) exceed or fall short

of its liabilities (or financial obligations) at the end of any given fiscal year. Over

time, increases or decreases in net position may serve as a useful indicator of

whether the financial position of the Government is improving or deteriorating.

The Statement of Activities presents information showing how the Government's

net position changed during the most recent fiscal year. All changes in net position

are reported on an accrual basis as soon as the underlying event giving rise to the

change occurs, regardless of the timing of related cash flows. Thus, revenues and

expenses are reported in this statement for some items that will only result in cash

flows in future fiscal periods (e.g., uncollected taxes, compensated absences, etc.).

Both of the government-wide financial statements distinguish functions of the government that

are principally supported by taxes and intergovernmental revenues (governmental activities) from

other functions that are intended to recover all or a significant portion of their costs through user

fees and charges (business-type activities).

The governmental activities of a municipality typically include categories such as general

government; administration; public safety; community development; public health and welfare;

1.38

1.79

2.22

2.28

2.52

2.77

4.05

1.63

1.86

2.60

2.36

2.47

3.41

3.35

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

Months

Months of General Fund Expenditures in

Unrestricted Fund Balance (Fig.2)

10-yr Average 5-yr Average

9

culture and recreation; and public works. Nashville’s governmental activities also include a

significant allocation to education.

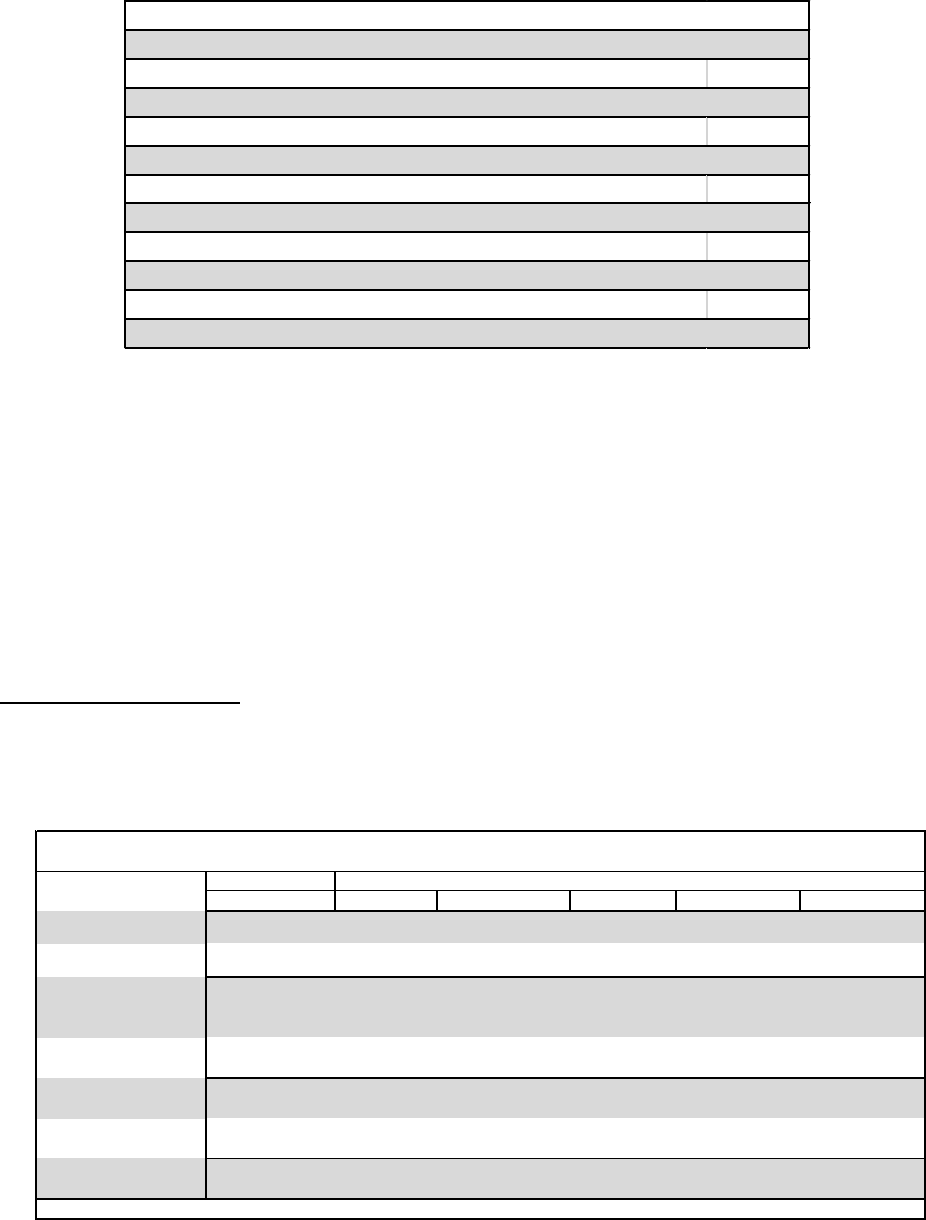

Nashville’s Net Position – As reported in its annual audited statement of net position, over the

ten-year period from 2010 through 2019, Nashville’s total net position has steadily declined to the

point that beginning in fiscal year 2015, liabilities began to significantly exceed assets.

Noteworthy in Figure 3 is the pronounced reduction that occurred in fiscal year 2018. This drop

was largely driven by the implementation of Government Accounting Standard No. 75 Accounting

and Financial Reporting for Postemployment Benefits Other Than Pensions (GASB 75), which

required governments to report their total unfunded liability related to retiree health care.

However, despite the implementation of GASB 75, Figure 3 illustrates that Nashville’s total net

position had begun to deteriorate at a rapid pace well before the total unfunded obligation for

other post-employment benefits (OPEB) was required to be recognized as a liability in the

financial statements.

As reported in this latest CAFR, net position decreased by an additional $242 million to a deficit

position of $3.433 billion. This decrease was driven in large part by a $673 million increase in

Nashville’s OPEB liability from $3.889 billion in 2018 to $4.562 billion in 2019. A significant portion

of the increase in 2019 was the result of a change in assumptions as applied by the City’s actuary.

(3,433,178)

(3,191,627)

(713,753)

(472,480)

(322,672)

87,113

209,936

331,048

500,076

757,334

(4,000,000)

(3,500,000)

(3,000,000)

(2,500,000)

(2,000,000)

(1,500,000)

(1,000,000)

(500,000)

-

500,000

1,000,000

Amounts in 000's

Nashville Total Net Position (Fig. 3)

10

Total net position as presented above is comprised of three categories:

• Net investment in capital assets consists of capital assets, net of accumulated

depreciation and reduced by outstanding debt that is attributable to the acquisition,

construction and improvement of those assets. Nashville’s capital assets include all of its

property and equipment, land, infrastructure, and major construction projects in progress.

The net investment in these assets is essentially calculated as their total cost, less:

o the cumulative amount that the assets have depreciated since being put in service,

and

o the outstanding debt that was incurred to finance their acquisition and construction.

The net investment amount should also be increased for debt proceeds on hand that have

not yet been spent on acquisition or construction.

• Restricted net position consists of restricted assets reduced by liabilities and deferred

inflows of resources related to those assets. The restricted category is typically the result

of externally imposed factors such as debt covenants or enabling legislation that requires

the government to maintain certain reserves. Examples of such restrictions include:

o Debt agreements that may require that a government hold a specific amount of

future principal and interest payments in reserve.

o Legislation adopted by states that require local governments to maintain reserves

for the stabilization of tax or utility rates in the event of volatile economic conditions

or catastrophic events.

• Unrestricted net position consists of net position which does not meet the definition of the

two preceding categories. As such, the unrestricted category is a primary indicator of the

extent to which the government’s financial strength is fortified in excess of resources that

have been either invested in capital assets or are required for compliance with externally

imposed restrictions.

11

While Nashville managed to maintain a positive total net position during the fiscal years from 2010

through 2014, a positive unrestricted net position has not been reported since prior to fiscal year

2009 as reflected in Figure 4 below:

Figure 4 illustrates that by excluding those portions of total net position that have been invested

in capital assets or that must be maintained by externally imposed requirements, unrestricted net

position has decreased at an average of over $179 million annually prior to a $2.4 billion drop in

2018.

The ability of a government to sustain itself is dependent on the extent to which it can generate

revenues in the form of taxes, fees, grants, and contributions to fund the cost of efficiently

providing required services and performing essential functions. Because the primary motive of

government is sustainability for the purpose of serving constituents versus profitability,

maximizing the excess of revenues over expenses is not a priority. However, generating sufficient

revenues to at least cover the expense of operations is imperative.

As reflected in Figure 5 below, Nashville’s expenses have exceeded its revenues for each of the

fiscal years for the period from 2010 through 2019. This recurring deficiency in revenues

compared to expenses has driven the decreases in total and unrestricted net positions described

above.

(4,500,000)

(4,000,000)

(3,500,000)

(3,000,000)

(2,500,000)

(2,000,000)

(1,500,000)

(1,000,000)

(500,000)

-

Amounts in 000's

Nashville Unrestricted Net Position (Fig. 4)

12

Figure 6 below presents a comparison of the average change in total net position as a percent of

total revenues among Nashville and the Peer Cities for the ten-year period from 2009 through

2018. As a result of Nashville incurring expenses in excess of revenues for each of the ten years

in the period, it has reported an average decrease in total position as a percent of total revenues

of 9%. This exceeds the average decreases of the other three Peer Cities with negative averages,

and reflects significant underperformance compared to those Peer Cities reporting positive

changes in total net position.

-

500,000

1,000,000

1,500,000

2,000,000

2,500,000

3,000,000

3,500,000

2019201820172016201520142013201220112010

Amounts in 000's

Nashville Comparison of Revenue to Expense (Fig. 5)

Revenue Expense

11%

6%

2%

-2%

-3%

-5%

-9%

-10%

-5%

0%

5%

10%

15%

Ten year average (2009 - 2018)

Increase (decrease) in Net Position as a % of Revenue

(Fig.6)

13

Figure 7 below presents a comparison of the average ratio of revenues-to-expenses among

Nashville and the Peer Cities for the same ten-year period. As would be expected, Nashville and

those Peer Cities reporting average decreases in total net position as reflected in Figure 6 are the

same entities for which the ratio of revenue-to-expenses are less than 1.0.

Tax Revenue

While strong growth in sales taxes, accommodations taxes and hospitality taxes reflect the

significant expansion in Nashville’s tourism industry, these sources are a relatively small portion

of City's overall revenue mix. Property tax, the City’s largest revenue source, has grown more

modestly especially in comparison to the growth in property values. This is in large part because

the property tax rate has not been increased since 2012.

Property Taxes - Property taxes comprise the largest source of revenue within the general fund,

accounting for approximately 53% of total general fund revenues for fiscal year 2018. Other major

revenue sources within the general fund and their percent of total general fund revenue for fiscal

year 2018 include:

• Local option sales tax (13.2%)

• Other taxes, licenses and permits (15.0%)

• Revenues from other governmental agencies (11.6%)

Within the general fund, property tax revenues and total revenues have grown at average rates

of 2.83% and 4.47%, respectively during the five-year period from 2014 through 2018.

Property tax growth has not kept pace with property values, particularly in recent fiscal years.

From 2016 to 2018, the estimated actual value of the General Services District (GSD) taxable

property increased by over 47%. Despite a reassessment that resulted in a comparable increase

1.17

1.07

1.04

0.98

0.98

0.92

0.88

-

0.20

0.40

0.60

0.80

1.00

1.20

1.40

Charlotte Denver Jacksonville Indianapolis Louisville Nashville Austin

Ratio of Revenue-to-Expense - 10 yr Average: 2009-

2018 (Fig. 7)

14

in total assessed values, property tax rates were rolled back for the Urban Services District (USD)

and the GSD as follows:

• USD – rates were rolled back from $4.516 per $100 of assessed value in 2017 to $3.155

per $100 of assessed value in 2018

• GSD - rates were rolled back from $3.294 per $100 of assessed value in 2017 to $2.755

per $100 of assessed value in 2018

While the above rollbacks were intended to result in a state-required revenue-neutral effect on

property taxes, Nashville did not anticipate extensive taxpayer appeals. As a result, despite

unprecedented increases in assessed values, property taxes for 2018 increased by less than 3%

and fell short of budgeted amounts.

Figures 8 and 9 below present comparisons of growth rates in assessed values to growth rates

in property tax revenue for each of the Peer Cities. The growth rates reflect 10-year averages for

the period from 2009 through 2018 and 5-year averages for the period from 2014 through 2018.

For the 10-year averages, growth in property tax revenues have exceeded the growth in assessed

values for each of the Peer Cities. However, Nashville’s property tax revenue growth of 2.8% has

significantly trailed the City’s 8.1% increase in assessed values. In the 5-year presentation, recent

robust economic conditions resulted in assessed values outpacing revenues for all the cities

except for Jacksonville and Charlotte. Nashville’s lag in revenue growth compared to assessed

values is much more pronounced compared to the 10-year presentation as the thriving economy

combines with Nashville’s 2017 rollback to widen the gap by an additional 5 percentage points.

-0.2%

-0.6%

0.7%

7.5%

2.9%

5.6%

8.1%

2.9%

1.5%

2.3%

8.7%

3.7%

5.8%

2.8%

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

10-yr Average Growth Rates - Assessed Value vs Property Tax

Revenue (Fig. 8)

Assessed value Property tax revenue

15

It is noteworthy that Tennessee law requires local governments that undergo a reassessment to

calculate a revenue neutral rate or “Certified Tax Rate”. However, a higher rate may be adopted

if Council takes the following required actions: 1) hold a public hearing regarding the “Certified

Tax Rate” versus the higher rate, and 2) adopt an ordinance or resolution establishing a tax rate

that exceeds the “Certified Tax Rate”. There is precedent for adopting a higher rate in cases

where a revenue neutral rate would produce an unbalanced budget due to expenditures out-

pacing revenue growth. According to web page of Nashville’s Property Assessor: “to date, this

was done (5) five times, but not during the prior three 2009, 2013 and 2017 reappraisals.” The

last increase in the property tax was in 2012 when the tax rate was increased $.53 or about 13%.

Reluctance to take such action was likely a contributing factor in diminishing Nashville’s

unrestricted fund balance significantly below those balances reported by the Peer Cities and the

level recommended by the GFOA.

Tax Growth Factors - In addition to property taxes, Nashville generates sales taxes,

accommodations taxes, and hospitality taxes as major revenue sources. These three categories

of tax revenue grew at the following average rates during the period from 2015 through 2019:

• Sales taxes 7.38%

• Accommodations taxes 12.53%

• Hospitality taxes 10.18%

Growth rates for these taxes have been driven largely by significant increases in population,

tourism, and overall spending.

According to the US Census Bureau, Nashville’s population grew by 10.9% during the period from

2010 to 2018, adding more than 60,000 people.

The Nashville Convention and Visitors Corporation (CVC), has reported that the number of visitors

to the City grew from 14.5 million in 2017 to 15.2 million in 2018, and increased to 16.1 million in

2019. The CVC also estimates that direct spending by visitors for the City’s New Year’s Eve

4.0%

2.7%

3.4%

10.7%

1.2%

10.2%

12.5%

7.2%

2.4%

2.6%

8.0%

3.6%

7.5%

2.1%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

Jacksonville Indianapolis Louisville Austin Charlotte Denver Nashville

5-yr Average Growth Rates - Assessed Value vs Property Tax

Revenue (Fig. 9)

Assessed value Property tax revenue

16

event increased from $22.3 million in 2017 to $23 million in 2018, and generated $23 million again

in 2019.

Accommodations and hospitality tax revenues specifically have grown as a result of the City

recently adding hotels and restaurants at a rapid pace. The CVC reports that for the period from

2013 to 2018 the number of hotel rooms increased by 16.6% from 26,175 to 30,509. At the time

of this report, it was estimated that an additional 20 hotels were expected to open in 2019. The

CVC also reports that the City added 113 new restaurants in 2017 and 133 in 2018.

Expense Analysis

This portion of the expense analysis compares growth rates in total expenses among Nashville

and the Peer Cities for the period from 2014 through 2018. It also evaluates expense trends for

Nashville during the period from 2015 through 2019 using the most recently issued 2019 CAFR.

Figure 10 below reflects 5-year average growth rates in total expenses for Nashville and the Peer

Cities ranging from 1.3% for Indianapolis, to 6.8% for Denver. At 4.3%, Nashville’s average rate

of growth in total expenses falls squarely in the median of the respective average growth rates for

the Peer Cities. These growth rates refer to expenses as reported on the full accrual basis in the

government-wide section of the respective CAFR’s of each city. Therefore, they largely consist

of operating costs and do not include investments in infrastructure or other capital expenditures.

The table below summarizes total expenses for the primary government including both

governmental and business-type activities. Total expenses grew from $2.553 billion in 2015 to

$3.167 billion in 2019, a 24% increase. Over the five-year period, growth rates for education, law

enforcement, fire department and code regulation and inspection expenditures were similar to the

overall growth rate. Public Works and Water and Sewer Services grew at significantly different

rates; Public Works expenditures grew at a much higher rate of 47.4% and Water and Sewer

expenditures grew at a much slower rate of 12.3%.

1.3%

2.7%

4.3%

4.7%

6.2%

6.2%

6.8%

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

8%

Total Expenses - 5-yr Average Growth Rates for fiscal years

2014 -2018 (Fig. 10)

17

$

%

Education - MNPS 907,504

$

1,124,977

$

217,473

$

23.96%

Law enforcement - MNPD 353,933

421,429 67,496 19.07%

Fire - MNFD 152,045 183,783 31,738 20.87%

Public works 191,499

282,226

90,727

47.38%

Regulation and Inspection

11,216

13,878

2,662

23.73%

Water and sewer 213,926

240,195

26,269 12.28%

All other categories 722,817 900,017 177,200 24.52%

Total primary government 2,552,940$ 3,166,505$ 613,565$ 24.03%

Expense Growth 2015 - 2019

(Fig. 11)

(amounts in 000's)

2015

2019

Increase

During the period from 2015 to 2019, an expansion in Public Works led to an increase in full time

employees (FTE’s) from 388 to 434, a growth rate of 12%. Water and Sewer employment grew

at a much more modest rate of 2%. Other line items were kept in check due to revenue

constraints. The expenditure trends are depicted in the following table:

# %

Education - MNPS 9,294 9,854 560 6.03%

Law enforcement - MNPD 2,898 3,067 169 5.83%

Fire - MNFD 1,206 1,252 46 3.81%

Public works 388 434 46 11.86%

Internal services

Fleet 95 106 11 11.58%

Technology 130 148 18 13.85%

Regulation and Inspection 111 118 7 6.31%

Water and sewer 713 727 14 1.96%

All other categories 3,459 3,644 185 5.35%

Total primary government 18,294 19,350 1,056 5.77%

Employment Growth 2015 - 2019 (Fig. 12)

(amounts in FTE's)

2015

2019

Increase

A major contributing factor to the growth in primary government expenses was the annual

budgetary practice of allocating funds for pay raises for Nashville employees. Consistently, pay

raises were allocated in annual budgets for cost of living adjustments, as well as range and step

increases. Since municipal government operations are labor intensive, particularly for the largest

departments (education and public safety functions), the annual pay adjustments are a significant

inflation factor on the total budget.

The other major contributing factor in the growth was the opening of new facilities, primarily

schools, and the expansion of services and programs. In order to staff the new facilities and

expand services from 2015 through 2019, a total of 1,056 new FTE’s were added to the Nashville

workforce. This represents a 5.87% increase in total FTE’s.

18

The following table highlights the driving factors for service increases for the period from 2015

through 2019:

2015

2016 2017 2018 2019

Education - MNPS

Operating costs

associated with three

new charter schools

and additional pre-K

classrooms

Operating cost

associated with

seven new charter

schools and two

new district schools,

100 new employees,

and investments in

“Reading Recovery”

the literacy program

Operating costs

associated with

one new charter

school and two

new district

schools, start-up

costs for English

language and

literacy initiatives,

and 250 new

positions,

including teachers,

bus monitors, and

special education

bus drivers

Further expansion of

the literacy and

English language

progra ms

Law enforcement - MNPD

Operating costs

associated with a new

Midtown Hills Precinct,

special events policing,

accreditation of the

crime laboratory, and

another $1 million for

the domestic violence

progra m

Additional special

events funding and

full year funding of

the accredited crime

lab

Six new officers for

domestic violence

programming and

seven additional

employees for

crime lab, special

events and youth

services

$3.7 million for

seventy new officers

Two new positions

for the secondary

employment unit.

Fire - MNFD

Four additional

paramedics

$1.9 million for

fourteen new fire and

inspection positions

Public works

$1.3 million for an

expansion of

cleaning crews

$1.7 million increase,

including additional

trans portation

planning and the

glass recycling

initiative

$2.3 million to

extend services to

areas of Davidson

County annexed into

the Urban Service

District

Regulation and Inspection

Three new

positions added

Summary of Explanations for Expense Growth by Fiscal Year

(Fig. 13)

19

As is the case with each of the Peer Cities, Nashville dedicates a significant portion of the City’s

budget to public safety and law enforcement. The FBI compiles an annual survey of local law

enforcement staffing metrics for US cities with jurisdictions exceeding 500,000 citizens. Based

on the survey conducted for 2016, Figure 14 below reflects a comparison of the number of police

officers and other department personnel comprising the police department staffs of Nashville and

each of the Peer Cities. The metrics are presented on a per capita basis of staff per 10,000

citizens. The comparison excludes Louisville as they did not submit a response to the survey.

As indicated by the table, the number of police officers and total personnel for Nashville is

consistent with the national median for all jurisdictions with over 500,000 people. It is also fairly

consistent with the Peer Cities. The somewhat lower numbers of officers per capita in Indianapolis

and Austin is likely driven by the specific demographics, income, and education levels existing

within those cities.

Nashville 20.9 25.5

Denver 21.9 25.7

Indianapolis 18.6 20.8

Jacksonville 20.0 33.5

Charlotte 19.4 25.7

Austin 18.9 24.7

Median for Cities >500K People 20.7 26.8

Law Enforcement Personnel per 10,000 Citizens (Fig. 14)

Officers

Total

personnel

It should be noted that recruiting officers is typically a challenge for medium to large U.S. cities. A

2019 article in The Tennessean described Nashville having experienced this issue based on a

Grand Jury study in which only 1,380 law enforcement positions were filled out of 1,511 that were

authorized.

20

Financial Forecast

Overview

This portion of the Study illustrates potential options for Nashville to generate additional property

tax and/or sales tax revenues for the purpose of decreasing City’s future reliance on one-time

revenues, while also building adequate fund balance reserves.

As a fiscal management tool, a well-developed forecast presents estimates of revenues,

expenditures and fund balances based upon past, current, and projected financial conditions.

Financial forecasts help identify trends such as structural imbalances between revenue and

expenditure growth, over-reliance on non-recurring revenues, and retention of reserves (fund

balance) within desired parameters. An effective forecast contributes to improved budgeting,

fiscal discipline and enhanced delivery of essential services.

Financial forecasting is an acknowledged best practice by the GFOA which recommends “that

governments at all levels forecast major revenues and expenditures. The forecast, along with its

underlying assumptions and methodology, should be clearly stated and made available to

stakeholders in the budget process. It should also be concisely presented in the final budget

document. The forecast should be regularly monitored and periodically updated.”

The Study incorporates a hybrid method of forecasting involving extrapolation and

regression/econometrics. Extrapolation uses historical data to predict future outcomes by

projecting historical outcomes forward, while regression/econometrics assumes a linear

relationship between independent variables such as cost drivers or inflationary factors and future

expenditures. A five-year forecast was developed, projecting forward from actual revenues,

expenditures, and changes in fund balance as reported in fiscal year 2019 CAFR.

Forecast Assumptions

The forecast estimates five years of general fund revenues, expenditures, and fund balances.

The forecast does not include Nashville’s other governmental funds, proprietary funds (e.g.

enterprise funds and internal service funds), fiduciary funds (e.g. pension trust funds), or the funds

of component units (e.g. Sports Authority Fund).

Revenues – Forecasted revenues are based on a five-year historical trend as reported for the

fiscal years from 2015 through 2019. Historical average growth rates by major revenue category

were applied to future periods to estimate revenues for fiscal years 2020 through 2024. Major

revenue categories include property taxes, sales tax, other taxes, license and permits,

intergovernmental revenues, and charges for current services.

Nashville’s recently announced amendments for the fiscal year 2020 budget include revenue

expected to be generated in the form of payments in lieu of taxes (PILOT) from the following

sources: 1.) water and sewer services and 2.) convention and tourism revenue. These revenue

estimates were not available at the time of the Study, and therefore are not included in the

forecasted revenues. Also, while Nashville has scheduled a property reassessment to occur in

2021, the baseline estimates presented in the forecast assumes no significant revenue changes

will occur (i.e. a revenue neutral tax rate is assumed).

Expenditures - Assumptions for future growth in spending categories were based on 1.) five-year

historical growth trends or 2.) common cost drivers such as health care trend rates, and cost of

21

living adjustments as measured by the consumer price index. The estimated rate of growth

assumed for each of the major expenditure categories is provided in Figure 15 below:

Personal services 4.50%

Utilities 2.50%

Professional services 2.50%

Travel, tuition, dues 2.50%

Communications 5.00%

Repairs and maintenance 4.50%

Internal service fees 4.50%

Other expenses 3.25%

Retiree benefits 9.00%

Miscellaneous 6.27%

Capital spending 4.00%

Expenditure Assumed Growth Rates ( Fig. 15)

Net transfers from the general fund of $109 million accounted for a significant portion of the

reduction in fund balance in 2019. Transfers represent amounts that a government may move

from one fund to another typically to cover expenditures in excess of revenues for a given fund.

For the 10-year period from 2010 through 2019, net transfers from the general fund increased

annually at an average rate of 14.7%. However, due to the extent that management controls

transfers, for purposes of the forecast, net transfers from the general fund were assumed to

remain unchanged for each of the five forecasted periods.

Recurring cost impact from projects included in the Capital Spending Plan for fiscal years 2020

and 2021 were added to the expenditure forecasts and estimated to grow by 4% in fiscal years

2022-2024.

General Fund Forecast

The results of the five-year forecast of Nashville’s General Fund revenues and expenditures are

summarized in Figure 16 below.

Actual

2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024

Revenues 1,075$ 1,122$ 1,162$ 1,215$ 1,272$ 1,331$

Expenditures 951 1,009 1,070 1,124 1,181 1,240

Revenues over

(under)

expenditures

124

113 92 91 91 91

Net transfers

out

(109) (109)

(109) (109) (109) (109)

Net change in

fund balance

15 4 (17) (18) (18) (18)

Beginning fund

balance

76 91 95

78 60 42

Ending fund

balance

91$ 95$ 78$ 60$ 42$ 24$

Forecasted

Amounts in

millions

Forecasted General Fund Condensed Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and

Changes in Fund Balance for the Years ended June 30, (Fig. 16)

22

Growth rates for property taxes and sales taxes, as driven by recent trends in economic

development, are assumed to continue as they have in the previous five fiscal years. However,

as reflected in historical trends, forecasted expenditure growth is assumed to out-pace the

forecasted growth in revenue. Key pressures on recurring expenditures include employee

compensation, pension, OPEB, debt service requirements, and operating costs associated with

the completion of capital improvements. The above forecast anticipates a fundamental structural

imbalance between recurring revenues and recurring expenses, and it indicates the need for

policy steps to protect and strengthen fund balance reserves in the general fund.

Forecast Scenarios

Three scenarios are presented below which incorporate certain assumptions as applied to the

“baseline” forecast reflected in Figure 16 above. An underlying assumption common to all three

scenarios is that Nashville’s anticipated decrease in fund balance beginning in fiscal year 2021 is

driven primarily by the need for additional revenues versus a significant reduction in expenditures.

And further, that the source of additional revenue is in the form of increased property taxes and/or

sales taxes.

The following scenarios illustrate the potential impact of property tax and/or sales tax increases

required to 1.) achieve targeted “unrestricted fund balance” reserves (as defined by the GFOA

and calculated as a percentage of estimated annual expenditures), 2.) provide additional funding

for affordable housing initiatives, and 3.) prevent future decreases in fund balance. For purposes

of the scenarios, the unrestricted fund balance percentages are based on the GFOA’s

recommended minimum of two months of expenditures in unrestricted fund balance:

• Scenario One– Determine the level of property tax increase required to:

o Eliminate the forecasted negative “net change in fund balance” as reflected in Figure 16

above for each of the four years 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024, and

o Implement a property tax rate increase as required to achieve an unrestricted fund

balance reserve of 10% of expenditures in 2021, 12% in 2022, 14% in 2023, and 16.7%

in 2024.

As reflected in the baseline forecast at Figure 16, the excess of expenditures and net transfers

over revenues depletes fund balance to $24 million by 2024. Scenario One (Figure 17) assumes

that property tax rates are adopted which increase revenues compared to the amounts reflected

in the baseline forecast by 5%; 7.5%; 7.5%; and 9% for the respective fiscal years 2021; 2022;

2023; and 2024

1

. This increase in property taxes serves to eliminate the annual negative change

in fund balance and reach the targeted fund balance percentages.

1

These percentages are not property rate increases, but represent increases in property tax revenue generated

from an assumed increase in rates.

23

Actual

2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024

Revenues (as

originally

forecasted)

1,075$ 1,122$ 1,162$ 1,215$ 1,272$ 1,331$

Property tax

increase

- - 30 45 48 59

Adjusted

revenues

1,075 1,122 1,192 1,260 1,320 1,390

Expenditures 951 1,009 1,070 1,124 1,181 1,240

Revenues over

(under)

expenditures

124 113 122 136 139 150

Net transfers out (109) (109) (109) (109) (109) (109)

Net change in

fund balance

15 4 13 27 30 41

Beginning fund

balance

77 92 96 109 136 166

Ending total fund

balance

92$ 96$ 109$ 136$ 166$ 207$

Scenario One - Forecasted General Fund Condensed Statement of Revenues, Expenditures,

and Changes in Fund Balance for the Years ended June 30, ( Fig. 17)

Amounts in

millions

Forecasted

• Scenario Two – Reflect the impact of the following:

o Implement a quarter cent sales tax increase to be allocated between the General Fund

and Metro Nashville Public Schools (MNPS), and

o Implement a property tax rate increase as required to achieve the same unrestricted

fund balance reserve of 10% of expenditures in 2021, 12% in 2022, 14% in 2023, and

16.7% in 2024.

Under Scenario Two (Figure 18) a quarter-cent sales tax rate increase is assumed to be effective

beginning in fiscal year 2021. Proceeds from the increased sales tax would be divided equally

between the General fund and MNPS. Also assumed is the adoption of property tax rates to

increase annual revenues compared to the amounts reflected in the baseline forecast by 0.5%;

2.5%; 2.5%; and 4%, for the respective fiscal years 2021; 2022; 2023; and 2024

1

.

2

The

combined increases in rates for property tax and sales tax serve to eliminate the annual negative

change in fund balance and reach the targeted fund balance percentages.

1

These percentages are not property rate increases, but represent increases in property tax revenue generated

from an assumed increase in rates.

24

Actual

2019 2020 2021 2022

2023 2024

Revenues (as

originally

forecasted)

1,075

$ 1,122

$ 1,162$ 1,215$ 1,272$ 1,331$

Sales tax increase

-

- 28 30 32 34

Property tax

increase

- -

2 15 16 25

Adjusted

revenues 1,075

1,122 1,192 1,260 1,320 1,390

Expenditures

951

1,009 1,070 1,124 1,181 1,240

Revenues over

(under)

expenditures

124

113

122 136 139 150

Net transfers out

(109) (109) (109) (109) (109) (109)

Net change in

fund balance

15

4

13 27 30 41

Beginning fund

balance

77 92 96 109 136 166

Ending fund

balance

92$ 96$ 109$ 136$ 166$ 207$

Scenario Two - Forecasted General Fund Condensed Statement of Revenues, Expenditures,

and Changes in Fund Balance for the Years ended June 30, (

Fig. 18)

Amounts in

millions

Forecasted

• Scenario Three – Reflect the impact of the following:

o Implement a quarter cent sales tax increase to be allocated between the general fund

and MNPS,

o Appropriate an additional $10 million for affordable housing, and

o Implement a property tax rate increase as required to achieve the same unrestricted

fund balance reserve of 10% of expenditures in 2021, 12% in 2022, 14% in 2023, and

16.7% in 2024.

Under Scenario Three (Figure 19) a quarter-cent sales tax rate increase continues to be

assumed with proceeds divided equally between the general fund and MNPS as required by

State law. Also assumed is the adoption of property tax rates to increase annual revenues

compared to the amounts reflected in the baseline forecast by 2%; 4%; 4%; and 5.5%, for the

respective fiscal years 2021; 2022; 2023; and 2024

13

.Finally, Scenario Three assumes an annual

$10 million appropriation for affordable housing, which has been reflected as an increase in

expenditures in Figure 19. The increases in rates for property tax and sales tax combined provide

the additional $10 million in appropriations, eliminate the annual negative change in fund

balance, and reach the targeted fund balance percentages.

1

These percentages are not property rate increases, but represent increases in property tax revenue generated

from an assumed increase in rates.

25

Actual

2019 2020 2021

2022

2023 2024

Revenues (as

originally

forecasted)

1,075$ 1,122

$

1,162$

1,215

$

1,272

$

1,331

$

Sales tax increase

-

-

28

30

32

34

Property tax

increase

-

-

13

26

26

35

Adjusted revenues

1,075

1,122

1,203

1,271

1,330

1,400

Expenditures 951 1,009

1,080

1,134

1,191

1,250

Revenues over

(under)

expenditures

124

113

123

137

139

150

Net transfers out

(109)

(109)

(109)

(109)

(109)

(109)

Net change in fund

balance

15

4

14

28

30

41

Beginning fund

balance

77

92

96

110

138

168

Ending fund

balance

92$

96$

110$

138$

168$

209$

Scenario Three - Forecasted General Fund Condensed Statement of Revenues, Expenditures,

and Changes in Fund Balance for the Years ended June 30, (

Fig. 19)

Amounts in

millions

Forecasted

26

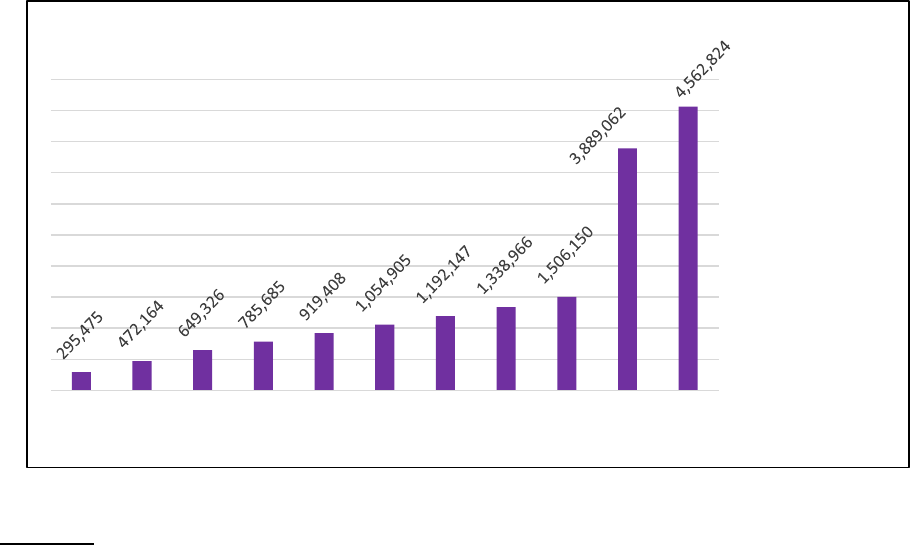

Other Post-Employment Benefits

As reflected in Figure 20 below, as of June 30, 2019, Nashville carried an OPEB liability of

approximately $4.6 billion which is an increase of $673 million over 2018. While new accounting

requirements (as summarized in the next section) resulted in a spike in fiscal year 2018, the City’s

OPEB liability had already been growing at an average annual rate of 34% from 2009 through

2017.

GASB 75

Beginning in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2018, a new accounting and reporting standard

became effective that required municipalities sponsoring OPEB plans to recognize the unfunded

liabilities of those plans in their statements of net position. OPEB plans provide retirement benefits

other than pensions, and usually consist of health coverage, but may also include life insurance

or other benefits.

The new reporting requirements were established by Statement Number 75 of the Government

Accounting Standards Board (GASB 75). Prior to 2018 and the implementation of GASB 75,

rather than reporting the full unfunded obligation related to their OPEB plans, municipalities were

only required to report a liability to the extent that it did not fulfill its annual required contribution

(ARC) as calculated by an actuary. In other words, in comparing the OPEB obligation to a

mortgage, the reported liability was basically limited to the total of any missed mortgage payments

versus the full outstanding mortgage balance.

GASB 75 significantly changed how the OPEB liability is calculated and reported, as

municipalities now must report the entire unfunded liability in their statements of net position. This

change has driven drastic increases in OPEB liabilities being reported in the statements of net

position for nearly all municipalities sponsoring defined benefit retiree health plans. As a result,

the unrestricted net position for many municipalities has been substantially decreased if not

-

500,000

1,000,000

1,500,000

2,000,000

2,500,000

3,000,000

3,500,000

4,000,000

4,500,000

5,000,000

20192018201720162015201420132012201120102009

Amounts in 000's

Fiscal years

Nashville's OPEB Liability (Fig. 20)

27

reduced to a negative balance. The effect for Nashville was even more pronounced as it had

been reporting negative unrestricted net position for each of the nine years preceding

implementing of GASB 75 (see Figure 4 at page 15).

It should be noted that GASB 75 applies only to an entity’s government-wide financial statements

and not to the governmental fund financial statements. As such, while the OPEB liability reduces

net position it does not directly affect fund balance beyond annual payments that are reported in

the governmental funds to cover benefits that have come due, or as assets placed in trust to fund

future benefits.

Funding

Figure 21 below presents a comparison of OPEB liabilities among Nashville and the Peer Cities.

As of June 30, 2018, Nashville’s OPEB liability amounted to 48% of total liabilities reported in its

governmental activities, exceeded only by Austin at 56%. Compared to the other five Peer Cities,

the OPEB liabilities of Austin and Nashville are significantly greater in terms of both in dollar

amount and as a percentage of total liabilities.

While there are a number of factors that affect the size and growth of an entity’s OPEB obligation,

the decision of whether or not to pre-fund the liability by setting assets aside for the payment of

future benefits is key. GASB 75 does not require that a municipality fund its OPEB liability.

However, it does stipulate that in terms of funding OPEB costs the liability as reported can only

be reduced through assets that are placed in a qualified trust established strictly for the purpose

of paying future benefits. As a result, once placed in the trust, assets are required to be used for

the payment of future benefits and cannot be accessed for any other purpose.

Nashville does not currently pre-fund its OPEB liability but rather uses the pay-as-you-go (or “pay-

go”) option in which benefits are only paid when they become due, versus as they are earned.

While most municipalities continue to use the pay-go method, a growing number are beginning to

contribute assets to qualified trusts in an effort to manage their OPEB liabilities. This is largely

56% 48% 20% 16% 9% 5% 3%

-

1,000,000

2,000,000

3,000,000

4,000,000

5,000,000

6,000,000

7,000,000

8,000,000

9,000,000

Austin Nashville Charlotte Louisville Indianapolis Denver Jacksonville

OPEB Obligation as a % of Total Debt - Fiscal Year

2018 (Fig. 21)

Total liabilites OPEB obligation

28

driven by the fact that the ongoing use of the pay-go method results in continued rapid growth of

an entity’s OPEB liability. Ever-increasing OPEB obligations have caused great concern among

stakeholders including taxpayers, investors, and unions. Unions for example, are highly

protective of their members’ retirement benefits, and therefore have a distinct interest in a

government’s ability as an employer to pay those benefits well into the future. Most notably, large

OPEB liabilities that are not being adequately managed have become a point of emphasis for

stakeholders including each of the credit rating agencies. As municipalities have become

increasingly aware of this, developing and implementing a plan to reduce their OPEB liabilities

has become a priority in order to mitigate the risk of a credit downgrade and the resulting increase

in the cost of borrowed funds.

Comparison of Peer City Liabilities and Benefits

The difference in the level of OPEB liabilities among Nashville and the Peer Cities is the result

several factors including funding methods, benefits provided, and required employee

contributions. Figure 22 below reflects key metrics for Nashville and each of the Peer Cities.

Austi n Charl otte Denver Indianapolis Jacksonville Louisville

Total OPEB liability

$3.889

billion

$2.525

billion

$605

million

$285

million

$233

million

$188

million

$345

million

Fiduciary net

position

$ - $ -

$89.3

million

$73.8

million

$11.9

million

$ - $ -

Net OPEB Liability

$3.889

billion

$2.525

billion

$516

million

$211

million

$221

million

$188

million

$345

million

Covered pa yrol l

$878

million

$968

million

$402

million

$542

million

$312

million

$379

million

$305

million

Annual OPEB

expens e

$243

million

$213

million

$26

million

$16

million

$18

million

$9.8

million

$47

million

Net OPEB liability as

a % of

covered-empl oyee

payroll

443% 261% 134% 39% 71% 49% 113%

Nashville

Peer Cities

OPEB Metrics Comparison ( Fig. 22)

For fiscal year 2018, three of the Peer Cities (Charlotte, Denver, and Indianapolis) had established

an irrevocable trust for purposes of pre-funding their respective OPEB liabilities. This is indicated

by the reporting of a “fiduciary net position” which serves to offset the total OPEB obligation and

results in a reduced “net” liability. As would be expected based on the size of their liabilities,

Nashville and Austin incurred the greatest annual expense of $243 million and $213 million,

respectively.

The total liability for each municipality is also presented relative to its “covered payroll” which

represents the compensation paid to employees who are active in the plan. At 443%, Nashville’s

net liability is over four times its covered payroll. This far exceeds Austin’s 261%, which itself is

significantly greater than the percentages of the other five Peer Cities. This is further pronounced

29

by the fact that both Nashville and Austin report traditional compensation paid to covered

employees that is roughly 2 to 3 times that of the other Peer Cities.

Noteworthy is the significantly reduced annual expense reported by the other five Peer Cities

compared to that of Nashville and Austin. While the decision to pre-fund future benefits on the

part of Charlotte, Denver, and Indianapolis contributes in part to this difference, it is also largely

due to the variance in benefits offered, and the extent to which employee contributions are

required. The following is a summary of the primary characteristics of each municipality’s

respective plans:

Nashville - Nashville provides insurance to both retirees and eligible family

members. Those retirees who were hired prior to 2013, can participate in the

Medical, Dental and Vision programs with the same subsidized premium rates as

offered to employees (the City contributes 75% and the retiree contributes 25%).

The plan for those over 65 requires that the employee must apply for Medicare

which acts as the primary insurer with the Nashville insurance secondary.

Those retirees hired after 2013 can also participate in the insurance program but

have a sliding scale for medical premiums as described below. A survivor of a

service pensioner or active employee with less than 10 years of service are not

eligible to participate

• 10 years, but less than 15 years Nashville 25%, Retiree 75%

• Between 15 – 16 years Nashville 50%, Retiree 50%

• Between 16 – 17 years Nashville 55%, Retiree 45%

• Between 17 – 18 years Nashville 60%, Retiree 40%

• Between 18 – 19 years Nashville 65%, Retiree 35%

• Between 19 – 20 years Nashville 70%, Retiree 30%

• 20 years or more Nashville 75%, Retiree 25%

While Nashville’s benefits are provided on a sliding scale, the percentages are more favorable to

employees than those of the Peer Cities. In addition, Nashville has based required employee

contributions on projected “pay-go” financing requirements which means contributions are at a

level sufficient only to cover benefits as they come due. Therefore Nashville’s liability continues

to grow at a rapid pace as employees accrue service time at a much faster rate than they

contribute.

Louisville – Louisville participates in a cost sharing plan operated by the State of

Kentucky Retirement System (KRS). All employees are eligible to participate, and

membership may be extended to certain beneficiaries under specific

circumstances. Health plan benefits are determined by length of service and the

type of retirement system in which the employee is enrolled. There is a sliding

scale for the portion paid by KRS. The scale ranges from 100% for over 20 years

of service to zero for less than 4 years of service in the case of those individuals

who enter after 2003. The City contributes 4.7% for each employee in the plan.

Plan members are required to contribute 1% of salary for the retirement insurance.

Louisville’s plan costs are significantly less than Nashville due largely to the fact that it is

participating in a cost-sharing plan in which the State funds much of the benefits.

30

Indianapolis -The City offers the retirees the option of enrolling in the City’s

medical plan but the retiree must pay both the employee and City share of the

premium. While there is no direct subsidy of the insurance premium, there is an

implicit subsidy since the older population would have a higher cost to provide

health care.

Because Indianapolis requires the employees to fund 100% of premiums, the City’s obligation is

limited to an implicit rate subsidy which results in a significantly smaller liability then if traditional

employer contributions were required.

Charlotte - The City has established an Employee Benefit Trust Plan in which

employees are offered a health plan with a sliding scale for premiums. A 20 year

employee pays nothing for a pre-Medicare policy and $176 for a Medicare

supplement plan. However the sliding scale results in employee premiums that

increase significantly as individuals are further from reaching 20 years of service.

Charlotte’s smaller liability compared to Nashville is driven primarily by a less-generous

sliding scale and the decision to fund future benefits by placing assets in trust.

Austin - As a matter of policy, the City Council determines the OPEB Benefits

annually. There is an Employee Benefit Fund that pays for any benefits provided.

Retirees have access to medical, Dental and Vision Insurance. For retirees under

the age of 65 with 20 years of services, the City pays the following:

• 80% of the retirees medical premium plus 80% for a Medicare supplement

• 50% of the premiums for retiree dependents, and

• 70% for surviving spouses.

There is a sliding scale of premium rates depending on years of service, with those

of less than 5 years of service receiving a 16% subsidy.

Like Nashville, Austin reports a covered payroll amount that is much greater than the Peer Cities,

indicating a larger city workforce and significantly more individuals receiving benefits. In addition,

the City’s plan is generous in its coverage of dependents and surviving spouses.

Jacksonville - The City has a self-insured health plan in which a retiree pays $593

per month for health insurance and a retiree and spouse pay $1,219 per month.

Jacksonville has maintained the smallest liability compared to other Peer Cities due primarily to

high employee premiums that are comparable to those paid in private employer health plans.

Denver - The City provides a health plan for retirees. The City’s monthly

contribution on behalf of the employee for the plan is $6.25 per year of service for

Medicare-eligible members ($125/month for a 20-year employee) and $12.50 per

year of service for members who are not yet Medicare-eligible ($250/month for a

20-year employee) .

Denver’s OPEB program includes multiple employers which share the cost of administering

several plans with the City, each with varying limits for entrants after specified dates. In addition

the City has begun placing assets in trust to offset the growth in its OPEB liability.

31

Tax and Fee Burden

This portion of the Study considers the estimated total cost of taxes and fees paid by residents

for key services and functions provided by state and local governments. Each of the Peer Cities

funds its operations differently depending on their individual structures and relationships to their

respective state governments. For example, some cities rely more heavily on property taxes

versus sales taxes that are often collected and disbursed by the states. In addition, the extent to

which charges for services are imposed to supplement tax revenues varies from city to city.

Therefore, in order to facilitate comparability of tax and fee burdens by city the various rates and

assessments imposed by each of the Peer Cities were applied to a representative Nashville

household having the following assumed characteristics:

• A two-person household in a $250,000 house (Based on data from Clear Capital and

reported by Kiplinger)

• Household income of $64,000 (Avg. Nashville household income per 2018 American

Community Survey)

• Annual spending on food, clothing and other items subject to sales tax, $25,000 (Estimate

derived from US Bureau of Labor Statistics)

• Consumption of water, 9000 gallons per month (Based on USGS website - average per

person consumption of 100 gallons per day and outside use of 100 gallons per day)

• Sewer use of 9000 gallons or sewer per month (based on water usage above)

• Electricity, 800 kWh per month (According to the US Energy Information Administration)

• Solid waste service (Based on standard residential service)

• Wastewater (Based on one equivalent residential unit)

Total taxes and fees per household were estimated for each municipality as reflected in the table

below. The taxes and fees selected for comparison were limited to those imposed by state and

local governments with the exception of certain electrical utilities operated by co-ops or other

privately owned entities. Under the above assumptions, Nashville’s combined burden for the

above taxes and fees ranges from 16% to 53% less than all of the Peer Cities. This suggests

that Nashville would not be at a competitive disadvantage with the Peer Cities, even if one or

more of these taxes or fees were to substantially increase.

Austin Charlotte Denver Indianapolis Jacksonville Louisville

Property tax 1,972$ 5,508$ 2,413$ 1,393$ 7,772$ 4,466$ 3,540$

Income tax

(1)

- - 3,360 2,969 1,293 - 4,608

Sales tax

(1), (2)

2,313 2,063 1,853 2,238 1,830 1,830 1,540

Water

(3)

497 1,120 772 636 635 472 490

Wastewater

(3)

1,282 1,353 1,032 698 1,008 819 597

Solid Waste 149 176 58 144 204 152 93

Electricity

(3)

1,249 680 1,005 792 1,169 1,219 1,053

Total 7,462$ 10,900$ 10,493$ 8,870$ 13,911$ 8,958$ 11,921$

(1) - Includes both state and local taxes

(2) - Includes hospitality taxes

(3) - Includes both base and volume charges

Nashville

Peer Cities

Tax/fee

Combined Tax and Fee Burden Comparison ( Fig. 23)

32

The primary inputs to estimate the amounts reflected in Figure 23 consist of individual rates,

fees and charges imposed by each of the Peer Cities and/or their respective state governments.

A summary of these inputs is presented in Appendix A.

33

Transit

An overview of the funding for Nashville’s transit system was performed to include a comparison

to transit funding of the Peer Cities. As an in-depth assessment of Nashville’s transit system was

beyond the scope of this Study, the focus was on the level and sources of funding, and the nature

of the transit services provided by the respective systems.

Nashville’s current transit system is comprised primarily of a basic network of bus routes and one

commuter rail line. In 2018 a major transit plan was presented via referendum. The plan

envisioned a major expansion of bus service, a light rail system and commuter rail routes.

However, the referendum was rejected by voters. The plan would have cost approximately $5.4

billion and would have funded five light rail lines, bus rapid transit lines, commuter rail and more