CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS

NATIONAL MONUMENT

HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY

March 1997

Jennifer D. Brown

National Park Service

Southeast Region

Atlanta, Georgia

CONTENTS

Figure Credits

iv

List of Figures

V

Foreword

Chapter One: Introduction

Chapter Two: The Struggle for Florida and Construction of

Castillo de San Marcos, 1565- 1821

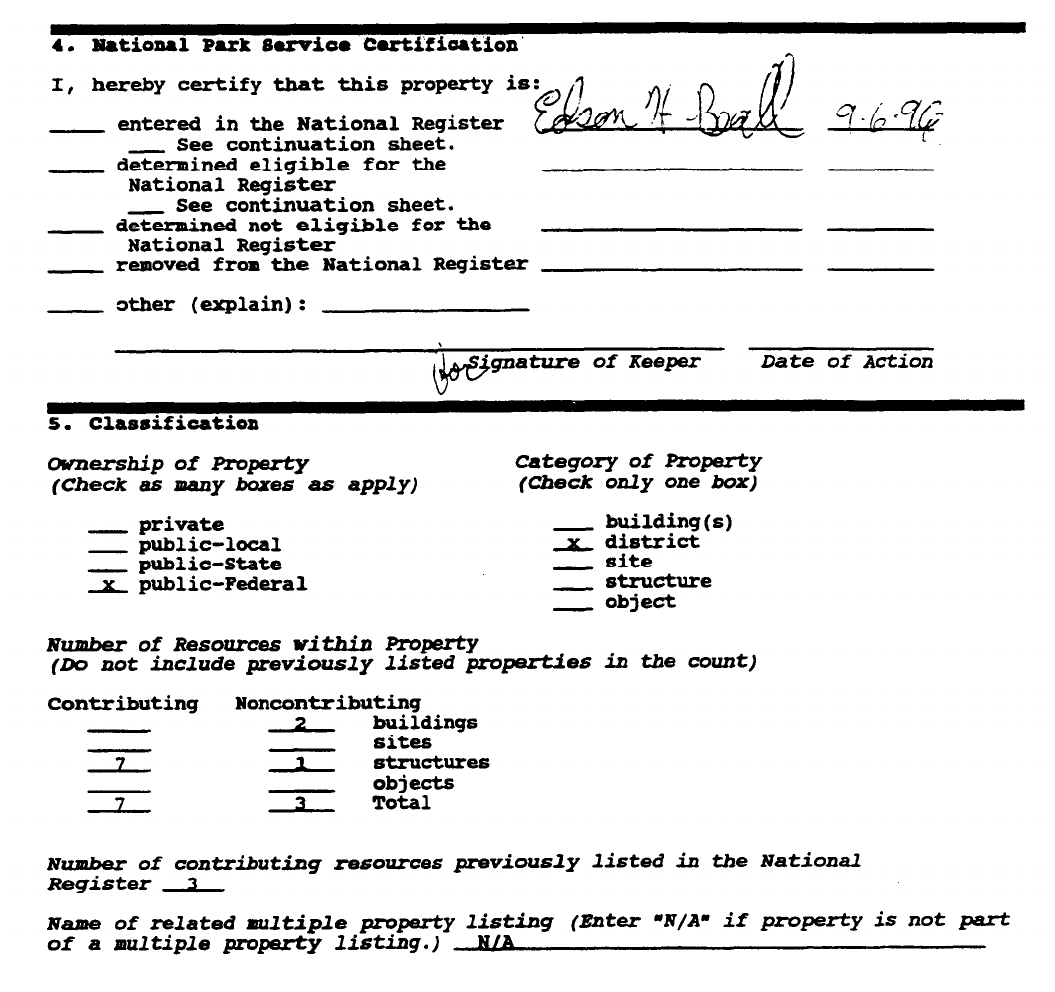

Associated Properties

Registration Requirements/Integrity

Contributing Properties

Noncontributing Properties

Chapter Three: The United States War Department at Fort Marion, 1821-1933

23

Associated Properties

32

Registration Requirements/Integrity

34

Contributing Properties

35

Noncontributing Properties

35

Chapter Four: Management Recommendations

Bibliography

Appendix A: Descriptions of Historic Resources

A-l

Appendix B: Historical Base Map

B-l

Appendix C: National Register Documentation

vii

1

7

18

20

21

21

37

39

C-l

III

F

IGURE

C

REDITS

Cover, clockwise from top left: Water Battery and City Gate, William Chapman for National Park Service, and aerial view of Castillo, Castillo

de San Marcos National Monument archives p. 2: William Chapman for National Park Service; p. 8,9: Florida State Photographic Archives; p.

Monument archives, p. 15: Jennifer D. Brown and Jill K. Hanson for National Park Service; p. 17: William Chapman for National Park Service;

p. 24, Castillo de San Marcos National Monument archives; p. 26: William Chapman for National Park Service; p. 27: Jennifer D. Brown and

Jill K Hanson for National Park Service, and William Chapman for National Park Service; p. 29,30: Castillo de San Marcos National Monument

iv

11: Christopher

Duffy,

The Fortress in The Age of Vauban and Frederick the Great, 1660-1789, p. 12,14: Castillo de San Marcos National

archives; p. 31, William Chapman for National Park Service; p. 32: Jennifer D. Brown and Jill K. Hanson for National Park Service.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

Figure 9.

F

IGURES

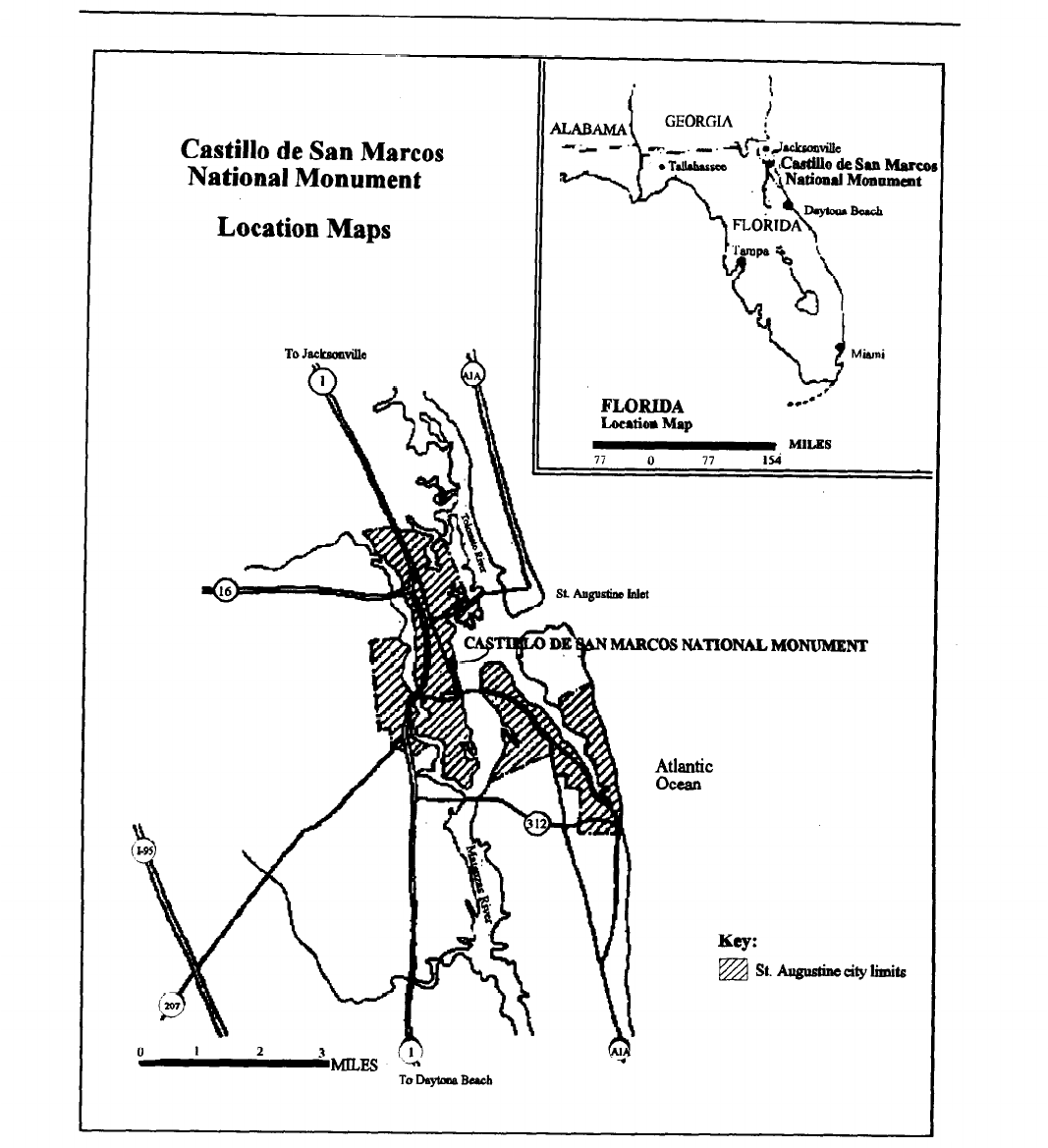

Location of Castillo de San Marcos National Monument

Plan of St. Augustine, 1660

Plan of a simple bastioned fort

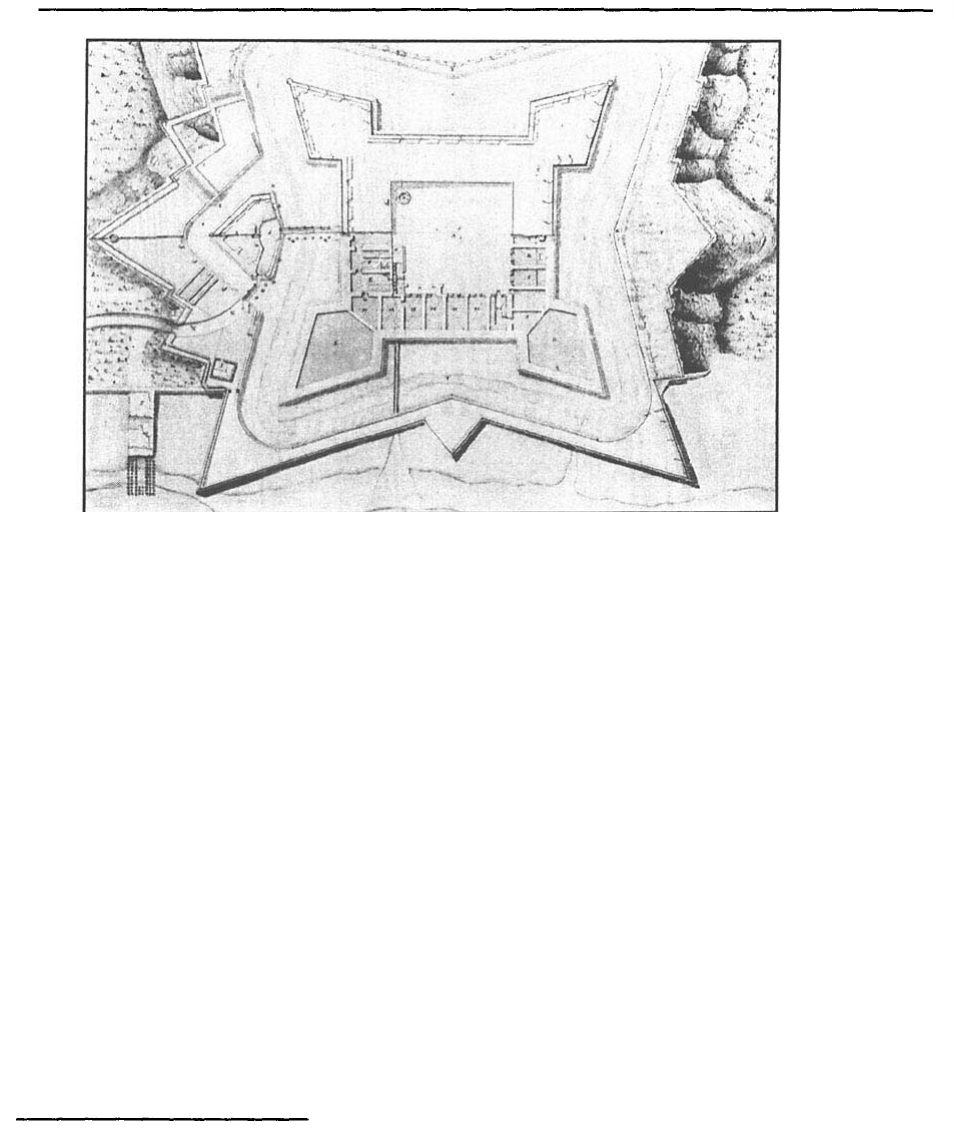

Plan of Castillo, 1675

Plan of Castillo, 1763

Ravelin viewed from west, 1995

Reconstructed Cubo Line viewed from northwest, 1991

City Gate viewed from northwest, 1991

Figure 10. Plan of Castillo, 1821

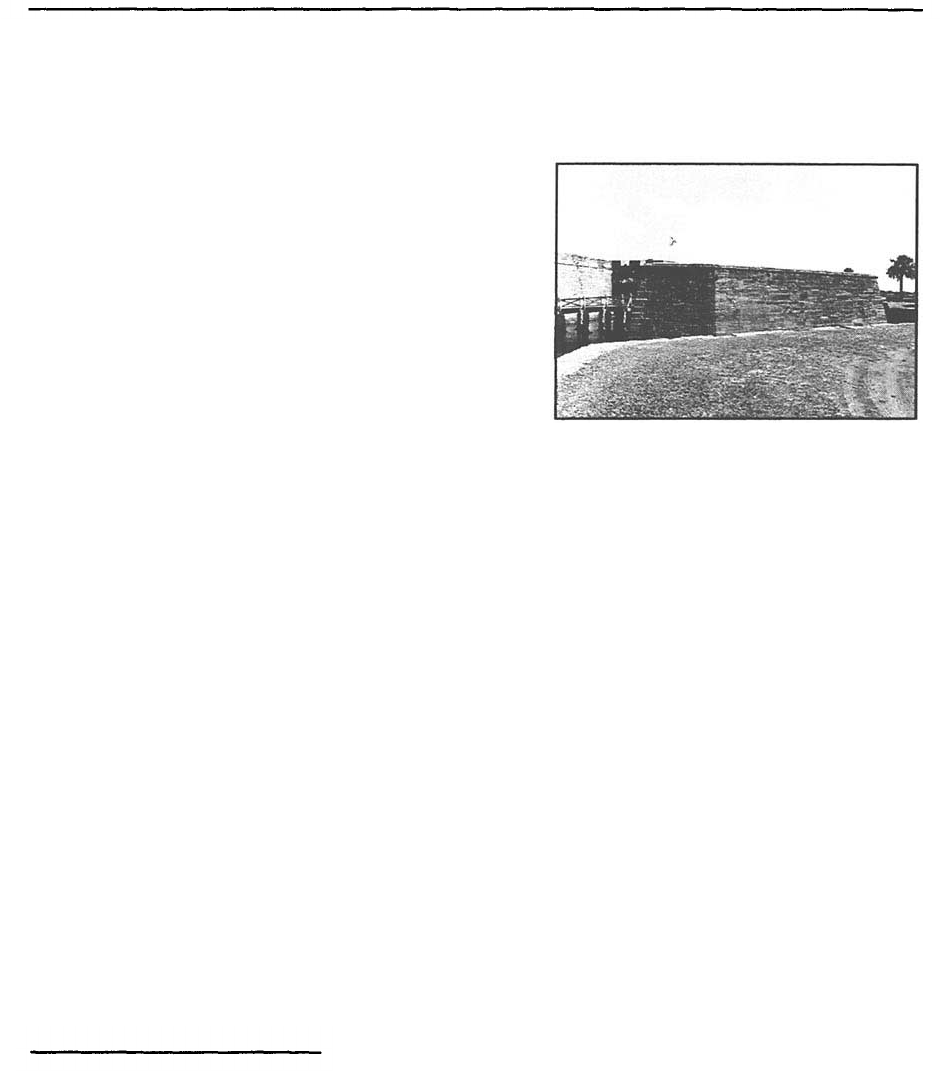

Figure 11. View of seawall from south, 1991

Figure 12. View of hot shot furnace from south, 1995

Figure 13. View of water battery from south, 1991

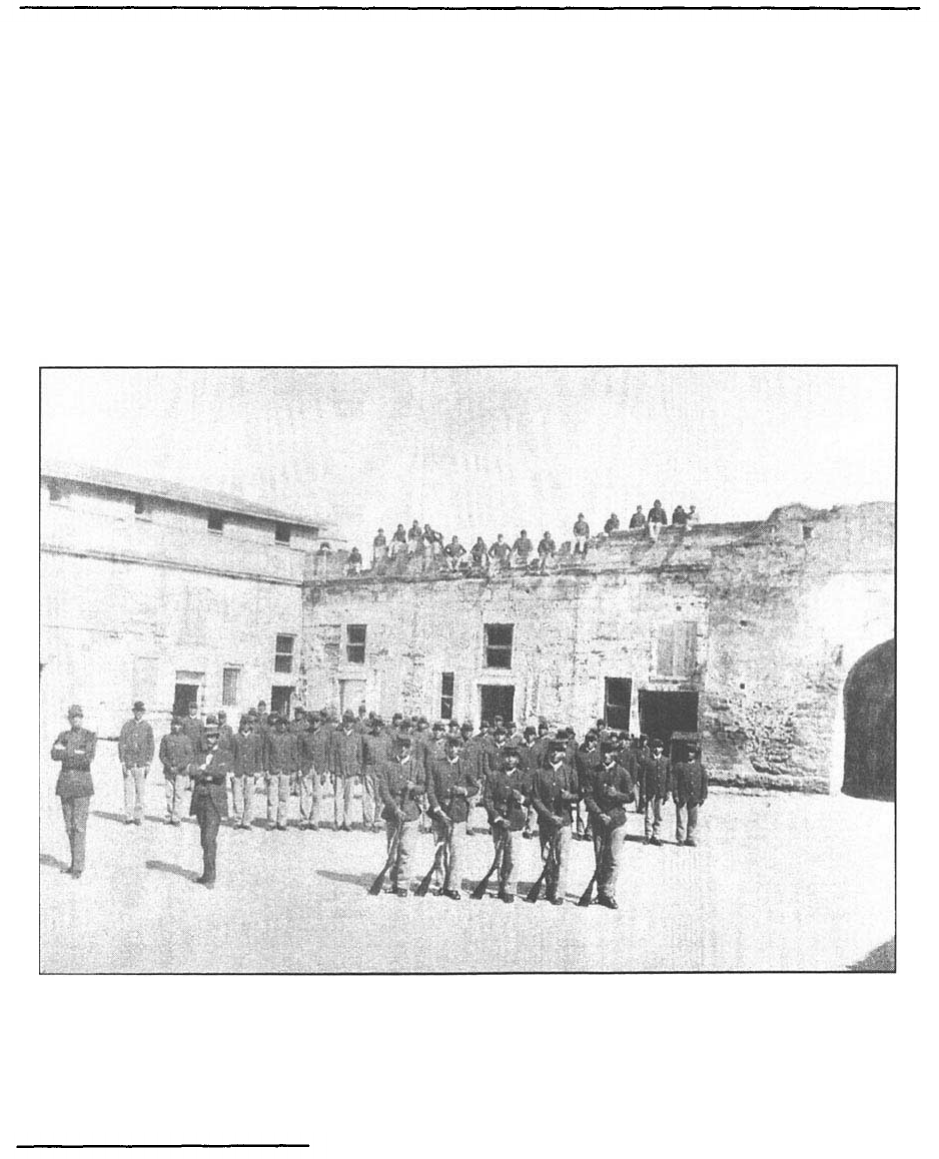

Figure 14. Fort Marion courtyard, c. 1870

Figure 15. Native American prisoners at Fort Marion, date unknown

Figure 16. View of moat and east wall from south, 1991

Figure 17. View of moat, covered way, and glacis from east, 1995

2

8

9

11

12

14

15

17

17

24

26

27

27

29

30

31

32

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés

v

Foreword

We are pleased to make available this historic resource study, part of our ongoing effort to

provide comprehensive documentation for all the historic structures and landscapes of National

Park Service units in the Southeast Region. Following a field survey of park resources and

extensive research, the project team updated the park’s List of Classified Structures, developed

historic contexts, and prepared new National Register of Historic Places documentation. Many

individuals and institutions contributed to the successful completion of this work. We would

particularly like to thank Castillo de San Marcos Superintendent Gordon Wilson, Chief of

Administration Bob Fliegel, Archivist Clara Gualtieri, and retired park historian Luis Arana, for

their assistance. We hope that this study will prove valuable to park management and others in

understanding and interpreting the historical significance of the park’s cultural resources.

Kirk A. Cordell

Assistant Superintendent, Cultural Resources

Southeast Support Offtce

March 1997

vii

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

Castillo de San Marcos National Monument in St. Augustine, Florida, contains the oldest

remaining European fortification in the United States. Built more than one hundred years after

the founding of St. Augustine by the Spanish in 1565, the Castillo stands as a reminder of a

century of conflict between the European powers for control of North America. Its bastioned

design also represents the conventions of military architecture and technology of its day. The

Castillo additionally illustrates the waning power of Spain in the Southeast, principally after the

United States won its sovereignty. The long history of Castillo de San Marcos and its distinctive

character and architecture attest to the significance of the monument to the story of the United

States and the building of a nation.

D

ESCRIPTION OF CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS NATIONAL MONUMENT

Castillo de San Marcos National Monument comprises approximately 20.48 acres in St.

Augustine, St. Johns County, Florida. The park lies north of St. Augustine’s central plaza and

fronts Matanzas Bay. Built as the northernmost Spanish stronghold in the southeastern United

States and as a defense against pirate attacks on St. Augustine, the Castillo was originally located

at the northern edge of the city, where it commanded the land and sea routes into the settlement.

Today, colonial St. Augustine extends south of the monument, while the modern city has grown

around this core in all directions.

The city of St. Augustine lies on the eastern coastal plain of Florida. It is a low-lying, sandy

area protected from the sea by a number of barrier islands. The San Sebastian River runs west

of the city and formed a natural boundary for the colony early in its history. A seawall and water

battery separate Castillo de San Marcos from the waters of Matanzas Bay on the fort’s east side.

The site of the Castillo is a rolling, grassy area sprinkled with a few trees. The outer portions

of the grounds are flat up to the glacis, which slopes upward toward the fort and roughly follows

the contour of the moat and covered way. The park area is irregular in shape, with much of its

western boundary following the contour of State Road A-l-A. West of the fort, beginning at

the bottom of the glacis near the northwest bastion, is the reconstructed Cubo Line. The defense

the gate.

work runs west from the glacis to the City Gate, interrupted by State Road A-1-A just east of

2

CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS NATIONAL MONUMENT: HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY

Figure I. Location of Castillo de San Marcos National Monument

INTRODUCTION

3

The Spanish founded St. Augustine in 1565 and, following an English pirate raid on the city

in 1668, began construction of Castillo de San Marcos in 1672. The Castillo had been completed

for less than a hundred years, however, when Florida became a diplomatic pawn. Control of

Florida passed to the English in 1763, only to revert to the Spanish twenty-one years later.

Finally, in 1821, Spain agreed to a treaty that transferred ownership of Florida to the United

States, and Florida became an American territory.

The United States War Department administered the Castillo, renamed Fort Marion, for more

than a century. During the early years, troops garrisoned in St. Augustine stored supplies at the

fort. The building also housed prisoners of war from a number of conflicts with Native American

groups during the nineteenth century. After the Civil War, Fort Marion was no longer necessary

to national defense, and although it remained an active fortification in name, the Castillo was

regarded as a historic relic by the military. In 1915 the War Department entered into an

agreement with the St. Augustine Historical Society to provide guide service to the public. The

Castillo was declared a national monument in 1924, and in 1933 its administration passed from

the War Department to the National Park Service.

The historic resources at Castillo de San Marcos National Monument include the Castillo,

moat, covered way, glacis, ravelin, City Gate, reconstructed Cubo Line, water battery, seawall,

and hot shot furnace. The Castillo, moat, covered way, glacis, ravelin, and Cubo Line date from

the First Spanish Period, while the City Gate dates from the Second Spanish Period. The water

battery, seawall, and hot shot furnace date from the War Department era. The park interprets

all of the structures as part of the evolution of the defenses of St. Augustine during the

seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The St. Augustine National Landmark District

exists near Castillo de San Marcos National Monument; its resources illustrate the growth of the

city which the fort was built to protect.

S

COPE AND PURPOSE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY

The Historic Resource Study (HRS) identifies and evaluates, using National Register criteria,

the historic properties within the national monument.

The study establishes and documents

historic contexts associated with the park and evaluates the extent to which the surviving historic

resources represent those contexts. The completed HRS will serve as a tool for future site

planning, resource management, and the continuing development of interpretive programs at the

monument.

CastilIo de San Marcos National Monument has been the subject of numerous investigations

undertaken by the National Park Service, including historic structure reports, archeological

investigations, and detailed studies of the fort’s history.

This report utilizes previous research

to evaluate the park’s resources through the development of historic contexts.

This HRS and

associated survey documentation will provide park management with information on historic

structures,

an interpretive framework for the park, and updated National Register

documentation.

4

C

ASTILLO

DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

N

ATIONAL

M

ONUMENT

:H

ISTORIC

R

ESOURCE

S

TUDY

Castillo de San Marcos National Monument was placed on the National Register of Historic

Places in 1966 with the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act. The Keeper of the

Register accepted the nomination of the park as a historic district in March 1977. This

documentation named the Castillo, City Gate, and water battery as contributing structures. The

contexts developed in this study will be used to supplement the original documentation and

support the addition of the moat, covered way, glacis, ravelin, Cubo Line, seawall, and hot shot

furnace as contributing properties within the district.

Survey Methodology

Goals of the historic resource survey of the Park are to 1) update the List of Classified Structures

(LCS) database for the Park for use by park management; 2) prepare a Historic Resource Study

for the Park; 3) update the Park’s National Register of Historic Places documentation; and 4)

assemble a comprehensive survey of structures consisting of a photographic record for each

structure built prior to 1950 and considered eligible for listing in the National Register. This will

be used in complying with Sections 106 and 110 of the National Historic Preservation Act of

1966.

The initial survey of Castillo de San Marcos was completed under a cooperative agreement

with the University of Georgia Research Foundation. The survey, led by Principal Investigator

William Chapman, concentrated on four structures within park boundaries, the Castillo, water

battery, City Gate, and reconstructed Cubo Line, and one structure located outside park

boundaries, the Orange Street Annex. Denise Larimore prepared a draft Historic Resource

Study based on the survey work and additional research.

In November 1995, Jennifer D. Brown and Jill K. Hanson, working under the direction of

the National Park Service Southeast Field Area, revisited the Park and surveyed six additional

structures, the ravelin, moat, covered way, glacis, hot shot furnace, and Tricentennial Marker.

Brown wrote the current Historic Resource Study based on the Larimore text and further

research and documentation.

Determination of Historic Contexts

This study evaluates the historic integrity and assesses the eligibility of the park’s historic

resources within two historic contexts. These contexts correspond to historic themes identified

by the National Park Service in its revised thematic framework and by the Florida State Historic

Preservation Office (SHPO). The Florida SHPO has identified thirty-five distinct historic

contexts for Florida history, many of which relate to the resources at Castillo de San Marcos

National Monument.

The following two historic contexts have been developed for the current study: 1) The

S

UMM

A

RY

OF

I

DENTIFICAT

I

ON

AND EVALUATION METHODS

Struggle for Florida and Construction of Castillo de San Marcos, 1565 - 1821; and 2) The United

States War Department at Fort Marion, 1821 - 1933.

I

NTRODUCTION

5

The first context, “The Struggle for Florida and Construction of Castillo de San Marcos,

1565-l821,” relates to the NPS themes “Peopling Places,” “ Shaping the Political Landscape,”

and “Changing Role of the United States in the World Community.” The context also relates

to several aspects of Florida history, including, “First Spanish, 1513-1763,” “British, 1763-

and the events that led the Spanish government to build the Castillo in St. Augustine. It also

briefly examines the Castillo as a typical defensive fortification for its time. The context further

discusses the turbulent eighteenth century in Florida, during which possession of the Castillo was

lost and later regained by the Spanish.

The second context, “The United States War Department at Fort Marion, 1821-1933,”

relates to the NPS themes “Shaping the Political Landscape” and “Changing Role of the United

States in the World Community.” The context also relates to the Florida SHPO´s chronological

contexts of the American period in Florida. In 1821 Spain agreed to cede Florida to the United

States, and the Castillo became property of the War Department, This context chronicles the

history of Fort Marion, as it was called, throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,

first as part of the American coastal defense system and later as the focus of early preservation

efforts in St. Augustine. It ends with the transfer of the Castillo from the War Department to

the National Park Service in 1933.

Historic resources within the park represent three periods of significance. The First Spanish

Period, 1565-1763, includes the initial settlement of Florida by the Spanish; this period is

represented by Castillo de San Marcos and the moat, covered way, glacis, and ravelin. The

Second Spanish Period witnessed the construction of the City Gate and Cubo Line as reinforcing

elements of the Castillo´s defense. This period encompasses the second occupation of Florida

by the Spanish from 1784-1821. Finally, the seawall, hot shot furnace, and water battery

States government administered the fort through that executive agency.

H

ISTORICAL BASE MAP DISCUSSION

The historical base map (Appendix B) depicts the existing historic resources within the park that

are documented in this study. The map shows the Park boundaries, nearby bodies of water, and

major area highways. National Park Service maps prepared by the Denver Service Center for

the Park’s General Management Plan served as the basis for the maps included in this study. The

historical base map does not attempt to depict a historic scene or identify nonextant historic

structures.

1782,” and “Second Spanish, 1783 - 1820.” This context considers the early history of Florida

represent the War Department period of the Castillo´s history, 1821 - 1933, when the United

CHAPTER TWO: THE STRUGGLE FOR FLORIDA AND

CONSTRUCTION OF CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS, 1565-1821

EXPLORATION IN FLORIDA AND THE FOUNDING OF ST.AUGUSTINE

The history of Castillo de San Marcos begins with the earliest European exploration in the New

World. In the century following the initial voyage of Christopher Columbus to the Caribbean

in 1492, Spanish conquistadores carved out a vast and wealthy overseas empire for Spain that

encompassed many of the Caribbean islands and the mainlands of Mexico, Central America,

Colombia, Venezuela, and Peru.

Channel, Spanish galleons carrying the riches of the Americas utilized the natural flow of the

Gulf Stream to propel them along the Florida coast and across the Atlantic. As a result, Florida

assumed a great deal of strategic significance: if Spain did not control Florida, pirates would use

its harbors as a base from which to attack the treasure fleets.

2

A number of attempts to settle Florida followed Ponce’s discovery, but their costly failures

led the Spanish king, Philip II, to forbid any further efforts at colonizing the region in 1561. The

monarch revoked his order three years later, however, as word arrived in Spain of the newly

established French settlement, Fort Caroline, on the St. Johns River in northeast Florida. In an

3

travelling north to the sheltered harbor of the land he named San Agustin. Hastily erecting

fortifications around the big house given to the Spaniards by the Timucua Indian Chief Seloy,

co., 1989), 8-9.

2

Verne E. Chatelain, The Defenses of Spanish Florida. 1565-1763 (Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of

Washington, 194l), 5-9.

Juan Ponce de León discovered the Florida peninsula in 1513, claiming the North American

continent for Spain. Ponce de León also discovered a significant water current crucial to the

success of Spanish empire—the Gulf Stream. Leaving the Caribbean by way of the Bahama

effort to protect Spanish interests in the New World, Philip commissioned Pedro Menéndez de

Menédez arrived on the coast of Florida in 1565, landing first at Cape Canaveral before

Menéndez and his men prepared to defend Spanish claims to Florida. An attack on Fort Caroline

1

George B. Tindall and David E. Shi, America: A Narrative History, 2d ed. (New York: W. W. Norton and

3

Ibid.. 7-17

Avilés to remove the French from Florida and colonize the area for Spain.

8

C

ASTILLO DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

N

ATIONAL

M

ONUMENT:

H

ISTORIC

R

ESOURCE

S

TUDY

while the French fleet was at sea eliminated most of the

settlers; the sailors later met the

i

r demise when their ships

wrecked, leaving them at the mercy of the Spanish. Most of

the men, including their leader Jean Ribault, were killed at the

most of North America for the Spanish king.

4

The Spanish settlers remained in Seloy’s village less than a year

due to growing discord between the natives and the

newcomers. The move out of the big house was the first of

several within a small area around Matanzas Bay that would

eventually lead them to the site of present-day St. Augustine.

During the first century of the Florida settlement, the Spanish

built nine different wooden forts for the defense of the colony.

Each of these had a short life span due to the ill effects of time,

weather, and insects on the structures. Enemy attacks destroyed the forts that were not

eliminated by natural forces.

5

The likelihood of attack and the shortage of food and supplies most threatened the safety and

stability of the colony. Settlers made few attempts to farm the land around St. Augustine

because of poor soil conditions and the threat of Indian attack on those who ventured too far

from the settlement. Except for produce raised in small plots around the houses, all of the

colony’s food, clothing, and other necessities came from Mexico and Habana, Cuba. Because

supply shipments were often detained in Mexico and occasionally lost at sea, the residents of St.

Augustine were often hungry and poorly clothed.

6

The threat of enemy raids on the town was always present, both from neighboring Native

American tribes angered by Spanish activities and from other European nations covetous of

Spain’s New World riches. The English in particular threatened Spanish control of the Florida

coast due to the success of privateers like Sir Francis Drake. In 1586, Drake led an expedition

against the Spanish at St. Augustine and took the city with relative ease, burning the wooden

4

Historical Society, 1965), 30-45.

5

Chatelain, 41: Luis Arana and Albert Manucy, The Building of Castillo de San Marcos (Eastern National

Park and Monument Association, 1977), 10-11.

6

Chatelain, 9

Figure 2. Pedro Menéndez de Avilés

direction of Menéndez. Within two months of landing in

Florida, Menéndez had reclaimed the vast territory comprising

T

HEFIRSTCENTURY INST.AUGUSTINE

Albert Manucy, Florida’s Menéndez: Captain General

of

the Ocean Sea (St. Augustine: St. Augustine

T

HE

S

TRUGGLE FOR

F

LORIDA AND

C

ONSTRUCTION OF

C

ASTILL

O

DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

‚ 1565-1821

9

during the assault, described the fort at that time, named San Juan de Pinos:

When the day appeared we found it built all of timber, the walles being none other

but whole Mastes or bodies of trees set vpright and close together in manner of a

pale, without any ditch as yet made, but wholy intended with some more time; for

they had not as yet finished al their work, having begunne the same some three or

foure moneths before: so as, to say the trueth, they had no reason to keepe it, being

subject both to fire, and easie assault.

8

Cates

’

s description illustrates the appearance of this early precursor to Castillo de San Marcos

and the vulnerability of wood forts to enemy attack.

Despite the inadequacies of the wooden forts erected in St. Augustine, the Spanish continued

to build and repair these structures, largely because they did not have the money to construct a

masonry fortification. The attack of

the pirate John Davis in 1668 provided

the stimulus for the construction of a

masonry fortress, however. Davis and

his men captured a Spanish supply ship

from Havana headed to St. Augustine

and sailed into the city without raising

suspicion among the townspeople. His

attack under cover of night revealed

once again the vulnerability of the

colony and the inadequacy of its

defenses. Fear that the pirates would

return to claim the city, which they had

Figure 3. Plan of St. Augustine, 1660

not destroyed, led the colonial

governor to request aid from officials

in Spain and Mexico. The Spanish queen approved the proposal for construction of a masonry

fortress at St. Augustine, and in 1672 the first stone was laid for Castillo de San Marcos

9

7

Amy Bushnell, “The Noble and Loyal City, 1565-1668,” in The Oldest City: St. Augustine, Saga

of

Survival,

ed. Jean Parker Waterbury (St. Augustine: St. Augustine Historical Society, 1983), 36.

Narratives and Letters (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1943), 8.

9

Arana and Manucy, 7-9.

fort, houses, and other buildings.

7

Thomas Cates, an English sailor who accompanied Drake

8

Albert Manucy, ed., A History

of

Castillo de San Marcos and Fort Matanzas from Contemporary

10

S

AN

M

ARCOS

N

ATIONAL

M

ONUMENT

:

H

ISTORIC

R

ESOURCE

S

TUDY

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY MILITARY FORTRESSES

Seventeenth century military engineering conventions dictated the design of Castillo de San

the castle useless as a form of defense and forced military engineers to develop a new type of

fortress able to withstand the force of cannon bombardment on its walls. The Italians first

developed the bastion system, which quickly spread across Europe and, by the seventeenth

century, dominated fortress design. European nations not only utilized bastioned fortresses at

home but also built fortifications in their colonial outposts in the same manner, altering designs

to suit local conditions and materials. Thus the Spanish officials in St. Augustine adopted the

bastion system for the early wood forts and, later, for the stone fortress, Castillo de San

Marcos.

l0

The bastion system evolved out of the medieval castle form. Engineers lowered castle walls

and placed mounds of earth in front of them, creating ramparts able to withstand cannon

bombardment. Moats remained an integral part of the defenses to prevent enemy forces from

scaling the sloped embankments and entering the fort. The circular castle tower evolved into the

angular bastion, which afforded protection to adjacent walls. Beyond the fortress walls engineers

placed a variety of masonry and earthen outer works that strengthened the fort’s defenses.

11

Bastioned forts centered on a plaza, around which the massive ramparts stood. The interior

of the ramparts sloped upward toward the fighting platform, called the terreplein. The

banquette, or firing step, rose above the terreplein and was protected by the parapet. Soldiers

fired on the enemy through embrasures (openings) in the parapet. On the exterior of the

rampart, facing the moat, a masonry scarp retained the earthen wall of the rampart. The opposite

side of the moat also had a masonry retaining wall, the counterscarp, above which stood the

covered way. A palisade protected the banquette for the covered way. The glacis, an earthen

bank kept clear of vegetation, sloped downward from the covered way into open country.

12

Seventeenth century forts were most often square in shape; the linear curtain walls projected

outward at the corners into diamond-shaped bastions, from which soldiers could view the

surrounding area in all directions. Ravelins were similarly shaped defensive structures, often built

in front of curtain walls to provide additional support to the points of the bastions, which were

most vulnerable to attack. Finally, outer defense works like counterguards and hornworks, built

of earth and wood and placed in front of the fort’s main body, provided additional strength to the

10

Luis Arana, “The First Spanish Period, 1668-1763: The Endurance of Castillo de San Marcos,” in Historic

Arana (National Park Service, 1986), 9-10; Chatelain, 39-40.

reprint, Ottawa: Museum Restoration Service, 1968), 2l-22.

12

Warfare (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985), 2.

C

ASTILLO DE

Marcos. The introduction of cannon as an implement of war late in the Middle Ages rendered

11

John Muller, A Treatise Containing the Elementary, Part

of

Fortification, Regular and Irregular (1746:

Structure Report: Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, C. Craig Frazier, Randall Copeland, and Luis

Christopher Duffy, The Fortress in the Age

of Vauban

and Frederick the Great, 1660-1789, vol. 2 of Siege

11

Figure 4. Plan of a simple bastioned fort

fortress and allowed the defenders to move farther into the landscape against the enemy. As a

complete defensive fortification, the bastioned fort and its outer defenses provided a great deal

of security to its occupants during a siege, although a persistent enemy might breach the walls

given sufficient time and manpower.

13

In 1669 Queen Regent Mariana of Spain approved the construction of a masonry fortress in St.

Augustine and sent the colony’s newly appointed governor, Manuel de Cendoya, to Mexico to

obtain the necessary funds. Cendoya arrived in St. Augustine in 1671, after stopping in Havana

to recruit masons, stonecutters, and lime burners to aid in construction. In Cuba he also acquired

the services of Ignacio Daza, an engineer, and Lorenzo Lajones, the master of construction.

14

Daza was an experienced military engineer familiar with contemporary fortification designs.

After examining possible locations for the fort, Daza and the military council in St. Augustine

determined that the site of the existing fortress, at the northern edge of town, was most

appropriate for the defense of St. Augustine. From this site, enemy fleets attempting to enter the

13

Ibid., 3.

14

Luis Arana, “Governor Cendoya’s Negotiation in Mexico for a Stone Fort in St. Augustine,” El Escribano 7

(Oct. 1970): 125-33.

T

HE

S

TRUGGLE FOR

F

LORIDA

AND

C

ONSTRUCTION OF

C

ASTILLO

DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

, 1565-1821

CONSTRUCTIONOF THECASTILLO

12

harbor could be bombarded easily from the safety of the fort. The location was also

advantageous for the protection of the colony from land attack from the north,

15

Preparations for construction began in 1671 as blacksmiths and carpenters made the

necessary tools and implements for quarrying and transporting stone to the construction site.

Coquina, a

soft

limestone made of cemented seashells, was locally available on Anastasia Island

and provided an adequate material with which to build the fortress.

Lime kilns were built in St.

Augustine to convert oyster shells into lime for construction. On October

2,

1672, Cendoya and

other royal officials broke ground for the foundation trench of the fort, and several weeks later

the first stone was laid.

16

Local Indians, convicts, African-

American slaves, and occasionally Spanish

soldiers labored alongside the skilled

workers imported from Cuba. Work

progressed at a steady rate on the fortress,

although funding shortages and disease

epidemics occasionally slowed construction.

By 1686, the main block of the Castillo was

complete. At that time, the outer curtain

walls and bastions of the fort were coquina,

while the interior walls and roof were wood;

the terreplein was made of tabby, a cement

made of lime and seashells, laid on top of

wood planks. The fort housed troop

Figure 5. Plan of Castillo, 1675

quarters, a chapel, and a number of

storerooms for the garrison. Ten years later, the moat and seawall were finished, thus enhancing

the Castillo’s defenses.

17

The War of Spanish Succession between England and Spain precipitated the first true test

of St. Augustine’s fortress. Governor James Moore of Carolina led an attack against St.

Augustine in 1702, hoping to drive the Spanish out of Florida, gain control of the Bahama

Channel for the English, and eliminate the threat of Spanish-French aggression against

Charleston. When the English reached St. Augustine, they bypassed the Castillo and occupied

the town; local residents fled to the fort for protection. The English besieged Castillo de San

Marcos for fifty days, until four Spanish men-of-war arrived from Cuba with fresh supplies and

15

Chatelain, 15

16

Arana, “First Spanish Period,” 6, 13

17

Luis Arana, David C. Dutcher, George M. Strock, and F. Ross Holland, Castillo de San Marcos and Fort

Malanzas National Monuments, Florida: Historical Research Management Plan (National Park Service, 1967),

8-9.

CASTILLO DE SANMARCOSNATIONALMONUMENT:HISTORICRESOURCESTUDY

13

reinforcements. Weary from the long siege and unable to match the new Spanish force, Moore

burned his ships, abandoned his supplies, and retreated overland to the St. Johns River. The

British set the city afire as they left, and the Castillo was the only structure to survive.

18

Following Moore’s attack on the Castillo and the total destruction of St. Augustine, the

Spanish sought to strengthen the city’s defenses by constructing a system of inner defense lines.

Between 1706 and 1763, the Spanish built four earth and log defensive structures around the

town. The Cubo Line formed the northern boundary of St. Augustine and, along with the

Rosario Line to the west, created a “line of circumvallation” protecting the city’s land

approaches. The homwork and Fort Mose line were built north of the Cubo Line, between the

North River on the east and the San Sebastian River on the west. These structures strengthened

the town’s defenses but proved difficult to maintain in the warm Florida climate.

19

Meanwhile, a new English threat from the north caused the Spanish to reassess the strength

of the Castillo’s defenses. General James Oglethorpe began settlements at Savannah in 1732 and

at Fort Frederica in 1736, thus staking the English claim to an area traditionally considered part

of Spanish Florida. As the English pressed south, Spanish Governor Manuel de Montiano

realized that Castillo de San Marcos was inadequate for the defense of the colony, even with the

addition of the outer defense works. An evaluation of the fort by Antonio de Arredondo, an

engineer from Havana, found that the stone walls were in good shape, but the wood in the

regarding conditions in St. Augustine:

Your Excellency must know that this castle, the only defense here, has no

bombproofs for the protection of the garrison, that the counterscarp is too low, that

there is no covered way, that the curtains are without demilunes, that there are no

other exterior works to give them time for a long defense; . . . we are as bare outside

as we are without life inside, for there are no guns that could last 24 hours and if

there were, we have no artillerymen to serve them.

21

Following the governor’s report, officials in Cuba sent soldiers, laborers, provisions, and

money to St. Augustine, The Cuban governor authorized construction of masonry vaults within

18

Arana and Manucy, 42.

19

Chatelain, 82.

20

Arana and Manucy, 42-43.

21

T

HE

S

TRUGGLE FOR

F

LORIDA AND

C

ONSTRUCTION OF

C

ASTILLODE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

1565-1821

interior rooms and the terreplein was rotted through.

20

The governor wrote officials in Cuba

Ibid., 43.

14

Figure 6. Plan of Castillo, 1763

the fortress walls and improved outer defense works. By 1739, the eight vaults along the east

curtain wall were completed, increasing the total height of the wall five feet. The outbreak of

war between England and Spain the same year slowed construction, however, and completion

of the project was postponed until the end of the war.

22

The War of Jenkins’ Ear, as the conflict between England and Spain was known, provided

Oglethorpe with an excuse to attack St. Augustine and oust the Spanish from Florida.

Oglethorpe sailed south from Fort Frederica in 1740 and lay siege to the Castillo for thirty-eight

days, but the onset of the hurricane season caused the English to abandon the effort and return

home. Construction on the vaults resumed after the war and was completed between 1750 and

1756. Work also continued on the covered way and the glacis until funds ran out in 1758.

23

In 1762 the Spanish undertook the last of their construction projects at the Castillo. Town

residents volunteered their labor to enlarge the covered way by five feet, and masons

constructed a six-foot-high stone parapet on top. Construction of the glacis was also completed

at this time. Engineers determined that the original ravelin was inadequate to the defense of the

fort’s entrance; therefore, a new, larger ravelin, capable of housing five cannon and an

underground powder magazine, was built by the end of the year.

24

23

24

Ibid., 52-53

22

Ibid., 43-46.

Ibid., 46-49.

CASTILLO

DE

S

AN

MARCOS NATIONAL MONUMENT:HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY

Before the ravelin was completed, news arrived in St. Augustine of the Spanish cession of

Florida to England under the terms of the treaty ending the Seven Years War, fought in America

as the French and Indian War from 1754 to 1763. All work on the Castillo ceased as the

Spanish prepared to evacuate the city. On July 21,

1763, the Spanish governor officially surrendered

Castillo de San Marcos to England. Thus ended the

occupation of St. Augustine by the Spanish, who

chose to abandon the city altogether rather than suffer

under British ru1e.

25

BRITISH OCCUPATION OF FORT ST.MARK

The Spanish left behind a fortified town with

approximately 400 residences and the nearly complete

Castillo de San Marcos, which the British renamed

Figure 7. Ravelin viewed from west, 1995

Fort St. Mark. The elimination of other European

powers from the eastern coast of North America diminished the strategic significance of St.

decade of occupation.

26

The outbreak of the American Revolution elevated the importance of St. Augustine to the

English, however. A British garrison was headquartered in town, and a large number of British

Loyalists from the southern colonies sought refuge within its walls. The small frontier outpost

quickly became a thriving city. Fort St. Mark received needed repairs to its defenses during this

time, including the reconstruction of the entrenchment and retrenchment lines north of the city.

The fortress housed troops, weapons, and equipment for the army. Additionally, the British

used the fort as a prison for rebel colonists. Hundreds of prisoners of war passed through St.

Augustine before being moved elsewhere or exchanged for imprisoned British soldiers and

27

Although the Continental Congress entertained plans to invade East Florida in 1778, the

British capture of Savannah late that year crushed those ambitions and ended rebel plots against

St. Augustine. Even as the American threat to the colony diminished, a new threat to St.

Augustine arose from the Spanish, who longed to regain a foothold in North America. Spain

declared war on England in 1779 but never launched an attack against East Florida.

25

Ihird., 53.

26

91: Arana and Manucy, 54.

27

Albert Manucy and Alberta Johnson, Fort Marion and the War of Independence (St. Augustine: National

Park Service, Southeastern National Monuments, 1941), 3-10.

THE STRUGGLE FOR F

LORIDA

AND CONSTRUCTION OF CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS 1565-1821 15

Daniel L. Schafer, “‘ Not So Gay a Town in America as This.. ,. 1763 - 1784,” in The Oldest City: St....

Augustine; therefore, the British undertook few alterations to the city’s defenses during the first

’

Augustine, Saga of Survival, ed. Jean Parker Waterbury (St. Augustine: St. Augustine Historical Society, 1983),

Loyalists.

16

C

ASTILLO DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

N

ATIONAL

M

ONUMENT

: H

ISTORIC

R

ESOURCE

S

TUDY

Nevertheless, negotiations following the war returned Florida to Spain, and the brief British

28

SECOND SPANISH OCCUPATION OF CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS

Most British citizens evacuated the colony with the military, although about 300 chose to

remain and declare allegiance to Spain rather than give up their homes and plantations. The

Spanish military escorted the new colonial government into St. Augustine, and the city was soon

repopulated with a variety of immigrants, including, “Spaniards, Englishmen, Americans,

Minorcans, Italians, Greeks, Swiss, Germans, French, Canary Islanders, Scots, and Irish.” A

sizable population of free blacks, slaves, and Native Americans resided throughout the colony

29

The new Spanish St. Augustine was not a tranquil city, however. Difficulties arising from

dependence on Cuba and Mexico continued as they had in the First Spanish Period, leaving the

town short on supplies and soldiers much of the year. Unrest along the Georgia border

exacerbated the colonial government’s problems. Runaway slaves from Georgia often sought

refuge in Florida, particularly in the interior of the peninsula controlled by Seminole Indian

tribes. As a result, Georgia plantation owners often crossed the border in search of fugitives,

raiding Indian towns and Florida plantations. Slaves belonging to Floridians and the Seminoles

were often stolen during the raids, and the angry slave owners retaliated with attacks against

30

The problems of the colonial government in East Florida escalated with the outbreak of the

French Revolution and the ensuing European conflict. The struggle against Napoleon drained

the Spanish government of resources, and her colonies in the Americas suffered as a result.

Nevertheless, the threat of American or French attack against East Florida inspired the Spanish

governor at St. Augustine to undertake improvements to the defenses of the city. The Spanish

rebuilt the Cubo Line, widening the moat and lining the earthwork with palm logs. They also

built a gate within the line, providing access to the city from the north. The renovations to the

Cubo Line and the new City Gate, which replaced an earlier gate built around 1740, were

28

John C. Paige, “Castillo de San Marcos: The British Years, 1763-1784,” in Historic Structure Report for

Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, Edwin C. Bearss and John C. Paige (Denver: National Park Service,

1983), 14-21.

29

Augustine, Saga of Survival, ed. Jean Parker Waterbury (St. Augustine: St. Augustine Historical Society, 1983),

130-1.

(Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1954), 31.

as well.

occupation of St. Augustine ended in July 1784.

the Georgians.

Patricia C. Griffin, “The Spanish Return: The People-Mix Period, 1784-1821,” in The Oldest City: St.

30

Rembert W. Patrick, Florida Fiasco: Rampant Rebels on the Georgia-Florida Border, 1810-1815

17

Figure 8. Reconstructed Cubo Line viewed from

northwest, 1991

Figure 9. City Gate viewed from northwest, 1991

completed in 1808, and the residents of St. Augustine waited anxiously to see if and when an

attack might come.

31

Florida had long been divided into two sections, west and east, with separate governors.

West Florida contained the area west of the Apalachicola River to the Mississippi River, while

the peninsula east of the Apalachicola comprised East Florida. It was in West Florida that the

first threat to Spanish control emerged. The American government had claimed possession of

West Florida following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, but the Spanish refuted the American

claim and retained control of the area. American citizens dominated the population of West

Florida, however, and in 1810 they revolted against Spanish authority, meeting little resistance

from the helpless Spanish government. The United States annexed the portion of West Florida

west of the Perdido River the following year.

32

This bloodless revolution encouraged land-hungry Georgians, who hoped to oust Spain

from the rest of Florida. A small group of planters with land in South Georgia and Florida

organized in 1812 as the East Florida Patriots and declared their independence from Spain.

With the backing of the United States military, the Patriots took the Spanish settlement at

Femandina on Amelia Island and advanced to the old site of Fort Mose, north of St. Augustine.

The Spanish governor at St. Augustine refused to surrender to the Patriots, however, and a

stalemate ensued during the summer. Attacks by the Seminole allies of the Spanish forced the

Americans to retreat, and the cause was lost when President James Madison withdrew his

support for the rebe1s.

33

31

Ibid.

32

33

Ibid., 83-193.

T

HE

S

TRUGGLE FOR

F

LORIDA AND

C

ONSTRUCTION OF

C

ASTILLO DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

,

1565-1821

Ibid., 10-12.

18

C

ASTILLO DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

N

ATIONAL

M

ONUMENT

:

H

ISTORIC

R

ESOURCE

S

TUDY

The primary impetus behind the Patriot Rebellion was greed for land and expansion of the

American nation. Similar motives propelled the United States in 1812 to declare war on

England, which controlled the northern part of the continent. Anxious to expand the nation’s

boundaries and rid its borders of foreign influence, expansionists utilized the violation of neutral

rights by the English and dissatisfaction with Spanish rule in Florida to rally public support

behind the War of 1812 and the Patriot Rebellion. Both conflicts were ill-conceived, however,

and consequently the goal of expansion was not reached. The Treaty of Ghent, which ended

the War of 1812, restored the pre-war boundaries of the United States, including the area of

West Florida annexed in 1811; East Florida remained in Spanish hands.

34

The affirmation of Spanish control of East Florida in the Treaty of Ghent did not extinguish

American desires for annexation of Florida. In 1817, just three years after the treaty was

signed, President James Monroe authorized a campaign against the Seminole Indians, who were

fighting with American settlers along the Georgia-Florida border. Monroe sent General Andrew .

Jackson to drive the Seminoles back into Florida. While Jackson was not authorized to attack

Spanish posts, he did so anyway, and by May 1818 he had conquered the Florida panhandle.

While Jackson’s forces never approached St. Augustine, the conquest of East Florida was a

motivating force behind his campaign.

35

In the wake of American encroachments in Florida and revolutions against Spanish rule in

Central and South America, the government in Spain finally acknowledged its inability to

maintain possession of Florida. In 1821, Spain agreed to cede Florida to the United States in

return for the retirement of Spanish debts owed American citizens. On July 10 of that year,

ownership of Castillo de San Marcos transferred to the American government with appropriate

fanfare, and the Spanish left the city of St. Augustine for the last time.

36

ASSOCIATED PROPERTIES

Castillo de San Marcos and the moat, ravelin, covered way, glacis, Cubo Line, and City Gate

are properties associated with the context, “European Powers in Florida: The Construction of

Castillo de San Marcos, 1565-1821.” All seven structures represent the struggle between

European nations for control of North America over two-and-one-half centuries in Florida.

Physical Characteristics

Castillo de San Marcos is a bastioned masonry fortification located north of the colonial town

of St. Augustine. The Castillo is built around a square plaza, the sides of which measure 320

feet, and has diamond-shaped bastions projecting outward at each corner. The coquina walls

34

Ibid., 144-5, 299.

35

Tindall and Shi, 237.

36

Ibid., 238-9.

T

HE

S

TRUGGLE FOR

F

LORIDA AND

C

ONSTRUCTION OF

C

ASTILLO DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

, 1565-1821

19

of the Castillo are thirty feet high, ten to fourteen feet thick at the base, and five feet thick at

the top. Vaulted casemates support the wide terreplein, and embrasures at intervals along the

top of the wall provided openings through which cannon could be fired.

The moat, covered way, and glacis surround the Castillo on the north, west, and south sides.

The moat originally encircled the fort on all sides, but the east side was filled with earth in 1842

to create a water battery. The remaining three sides of the moat are framed by coquina walls

and contain water; the moat is approximately forty-two feet wide. The covered way is the flat,

grassy area between the glacis and the moat; a masonry wall five feet high separates it from the

glacis. The glacis is the open, sloped area beyond the covered way that stretches into the

landscape. The ravelin is the triangular masonry structure built to afford additional protection

to the corners of the bastions. The ravelin is located within the moat on the south side of the

fort and is connected to the main structure by a reconstructed drawbridge.

The Cubo Line begins at the covered way on the northwest side of the fort and proceeds

250 feet west toward the City Gate. The line is a reconstruction of the earthwork built in 1808

by the Spanish. The northern and southern faces of the defense work are concrete cast to

imitate the palm logs of the original wall. Between the concrete walls is earthen infill, with a

depth of forty-five feet. A dry moat exists along the north face of the Cubo Line.

The City Gate of St. Augustine originally was part of the Cubo Line, providing entrance into

the city from the north. Two four-foot-square coquina pillars frame an opening twelve feet

wide. Each pillar has a cove-molded pyramidal cap with a round finial and a height of fourteen

feet. On either side of the pillars, low stone walls thirty feet long by eleven feet wide extend to

meet reconstructed portions of the Cubo Line. North of the gate, a coquina bridge spans a

shallow moat.

Associative Characteristics

Castillo de San Marcos and the moat, covered way, glacis, ravelin, Cubo Line, and City Gate

are closely associated with the struggle for domination of the New World by European powers.

The Spanish built the Castillo and its related structures, the moat, covered way, glacis, and

ravelin, to protect the colony at St. Augustine and Spanish interests along the eastern coast of

North America. Throughout the periods of Spanish and English occupation of Florida, the

Castillo was central to the defense of the colony from enemy forces.

The Cubo Line originated during the eighteenth century, while the Castillo was still under

construction. Following the English siege of St. Augustine in 1702, the Spanish government

recognized the need for improved defenses for the city and undertook construction of defense

works around the fort and town. The Cubo Line formed the innermost line of defense; north

of the line, the hornwork and Fort Mose line provided additional barriers between the land

approach to the city and the Castillo. The Cubo Line and the Rosario Line, another defense

work, created the line of circumvallation that walled St. Augustine on the north, west, and south

sides. Built of earth and wood, these outworks had short life spans in the subtropical Florida

climate and were periodically reconstructed. The Spanish rebuilt the Cubo Line in 1808 and,

20

CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS NATIONAL MONUMENT: HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY

at the same time, built the City Gate to allow entrance into St. Augustine through the line. The

Cubo Line and the City Gate are closely associated with the attempts to strengthen the defenses

of the city during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Significance

Castillo de San Marcos is nationally significant under National Register Criteria A and C. The

Castillo represents the military struggle that occurred in Florida between the European powers,

particularly Spain and England, for control of North America, It also illustrates the early

diplomacy of the United States government, which culminated in the cession of Florida to the

United States in 1821. Indeed, in many ways the Castillo represents the history of the nation

from the time of the first permanent European settlement, through the struggle for empire

between Spain and England, to the emergence of the American republic. The Castillo is also

architecturally significant as the oldest masonry fortification remaining in the United States.

Built using the bastion system of fortress construction popular in Europe, Castillo de San

Marcos remains an important example of early military architecture in the United States.

The moat, covered way, glacis, and ravelin are nationally significant structures under

Criteria A and C. These four structures were integral to the protection of the Castillo and

designed as significant elements of the city’s defenses. As a result, they represent the battle for

control of the eastern shores of North America by the European powers from the time of

Florida’s discovery to 1821. The structures are also architecturally significant, representing the

military theories prevalent at the time of their construction and the execution of these European

designs in the New World. Together with Castillo de San Marcos, the moat, covered way,

glacis, and ravelin contribute to the understanding of the struggle for the Americas and the early

military architecture that resulted from it.

The Cubo Line and City Gate contribute to the significance of the district under Criteria A

and C. The Cubo Line is an accurate reconstruction of the line as it appeared in 1808, when

the Spanish rebuilt the structure and added the City Gate. The Cubo Line and City Gate

represent early additions to the defenses of St. Augustine, and thus several centuries of struggle

between European powers for control of Florida. As military fortifications, the Cubo Line and

City Gate are typical designs for the period and thus have significance as early nineteenth-

century military structures.

REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS/INTEGRITY

Castillo de San Marcos National Monument was listed on the National Register in 1966, and

documentation accepted in 1977 identified a district with three contributing historic structures,

including the Castillo and the City Gate. Both the Castillo and the City Gate have retained

integrity of location, design, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association. The Castillo has

additionally retained integrity of setting. The setting of the City Gate has lost some integrity

but the eligibility of the structure has not been significantly diminished by the changes.

due to the construction of modern roadways that have physically separated it from the Castillo,

21

The moat, covered way, glacis, and ravelin were included in the original nomination but not

individually listed on the National Register. These are independent structures worthy of listing

as contributing resources; each demonstrates integrity of location, setting, materials,

workmanship, feeling, and association. The moat was altered in the mid-nineteenth century

when the east side was filled for construction of a water battery. This alteration changed the

design of the structure but did not significantly impact its integrity. The covered way, glacis,

and ravelin retain integrity of design.

Reconstructions must demonstrate a high level of historical accuracy and integrity in order

to be eligible for the National Register. The Criterion Considerations require that

reconstructions be placed in appropriate settings as part of a master plan of restoration, in which

no other structure with the same association remains. The Cubo Line meets all of these criteria.

The reconstruction is built on the original location of the Cubo Line, which was identified

through archeological investigation. No physical or archeological remains exist from the other

outer defense works constructed at the same time as the Cubo Line. Therefore, the

identification of the location of the original Cubo Line provided a unique opportunity for the

reconstruction of a significant structure related to the long history of Castillo de San Marcos.

The Cubo Line is an accurate reconstruction, exhibiting integrity of location, design, setting,

feeling, and association. The line provides an important visual link between the Castillo and the

City Gate, a link that had previously been absent and hindered interpretation of the City Gate

at Castillo de San Marcos National Monument. While the reconstruction does not employ the

original material, which was palm logs, the choice of concrete is justified both for its longer life

span and by the careful casting of the concrete to simulate the appearance of palm logs. During

the reconstruction, precautions were taken to protect the archeological remains of the original

Cubo Line. The Cubo Line is thus eligible for the National Register due to the historical

accuracy of the reconstruction and the lack of other structures with the same association around

the fort.

C

ONTRIBUTING PROPERTIES

Castillo de San Marcos (1672-1756)

Moat (1672-1696)

Covered way (1672-l762)

Glacis (1672-1758)

Ravelin (1762)

City Gate ( 1808)

Cubo Line (1808; reconstructed 1963)

N

ONCONTRIBUTING PROPERTIES

None

T

HE

S

TRUGGLE FOR

F

LORIDA AND

C

ONSTRUCTION OF

C

ASTILLO DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

, 1565-1821

CHAPTER THREE: THE UNITED STATES

WAR DEPARTMENT AT FORT MARION, 1821-1933

ESTABLISHING THE AMERICAN TERRITORY OF FLORIDA

A ceremony held July 10, 1821, at Castillo de San Marcos officially marked the transfer of East

Florida from Spain to the United States. Some Americans were unenthusiastic about acquisition

of territory that U. S. Representative John Randolph described as “a land of swamps, of

quagmires, of frogs and alligators and mosquitoes.

„37

Nevertheless, many other citizens,

particularly in the South and West, viewed the removal of the Spanish from the east coast as

essential to the prosperity and sovereignty of the nation. Supporters, including President James

Monroe, also believed that acquisition of Florida would pacify the Seminole Indians and bring

an end to attacks on white settlers.

38

The newly established territory united East and West Florida under one government, and

Monroe appointed Andrew Jackson its first military governor. American farmers began to

migrate into the territory soon after its acquisition, carving farms and plantations out of the

fertile wilderness of north Florida. Other citizens moved into the territory’s largest towns, St.

Augustine and Pensacola, mingling with former Spanish citizens who remained in Florida under

American rule. The United States Army established outposts throughout the territory; the

garrison at St. Augustine occupied Castillo de San Marcos and several Spanish government

buildings. In 1825, the War Department changed the name of the Castillo to Fort Marion, in

honor of American Revolutionary War General Francis Marion.

39

The Spanish had limited expenditures on building maintenance and improvements during

their final years of occupation because of funding shortages and uncertainty about the future of

the colony. As a result, many of the public buildings and private residences in St. Augustine

were in poor condition at the time of American occupation. At Fort Marion, cracks in the

37

151.

38

Ibid.

39

Augustine, Saga of Survival, ed. Jean Parker Waterbury (St. Augustine: St. Augustine Historical Society, 1983),

Quoted in George E. Buker, “The Americanization of St. Augustine, 1821-1865,” in The Oldest City: St.

Ibid., 152: Arana, et al., 18

24

C

ASTILLO

D

E SAN

M

ARCOS

N

ATIONAL

M

ONUMENT :

H

ISTORIC

R

ESOURCE

S

TUDY

Figure 10. Plan of Castillo, 1821

T

HE

U

NITED

S

TATES

W

AR

D

EPARTMENT AT

F

ORT

M

ARION

, 1821-1933

25

masonry walls, a crumbling water battery, and leaks in the terreplein were among the structural

problems identified by American engineers. These problems made the fort uninhabitable;

therefore, the St. Francis barracks, built during the British period to house soldiers, were

repaired to house the garrison, and Fort Marion was used to store supplies and provisions. The

War Department also permitted local authorities to use several casemates as a prison.

T

HE SECOND SEMINOLE WAR, 1835-1842

The belief that American occupation of Florida would provide security against warring Indian

tribes helped gamer public support for the acquisition of Florida in 1821. It was soon clear,

however, that fighting between the Seminoles and white settlers had continued unabated, and

the government was forced to intervene in order to protect American lives and property.

Negotiations in September 1823 resulted in the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, which established a

four-million-acre reservation in the center of the Florida peninsula for the Seminole tribes. The

treaty also required the government to provide money and supplies during the move and to

41

The move to the reservation progressed slowly, but most tribes had relocated by 1826.

Hunger soon forced the Indians off the reservation in search of food on neighboring farms;

white settlers responded by petitioning the federal government for removal of the tribes to the

West. In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the government to

trade land west of the Mississippi River for Native American lands in the east and to assist in

the removal of the tribes to their new homes. In the Treaty of Payne’s Landing (1832) and the

Treaty of Fort Gibson (1833), Seminole leaders agreed to removal, but soon after they reneged

and declared both agreements invalid. Tensions mounted between the Indians and Americans,

reaching a climax in December 1835 with the murder of the federal Indian agent and several

others at Fort King and the ambush of an American detachment from Fort Brooke.

42

The Second Seminole War raged for seven years throughout the peninsula and ultimately

resulted in the death or removal of virtually all Native Americans from Florida. St. Augustine

became an important base of operations for the United States Army during the early stages of

the war, and the population expanded with the influx of soldiers and refugees from neighboring

plantations. While no skirmishes occurred in the city, attacks in outlying areas kept citizens on

40

Historic Structure Report for Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, Edwin C. Bearss and John C. Paige

(Denver: National Park Service, 1983), 36-44.

41

Buker, 161; John K. Mahon, History of the Second Seminole War, 1835-1842 (Gainesville, FL: University

of Florida Press, 1985),29-50.

42

Mahon, 5l-61, 72-83, 101-6.

40

reimburse tribesmen for improvements on the land they were forced to abandon.

Buker, 152: Edwin C. Bearss, "Castillo de San Marcos: The War Department Years, 1821-1933,” in

26

C

ASTILLO

D

E

S

AN

M

ORCOS

N

ATIONAL

M

ONUMENT

:H

ISTORIC

R

ESOURCE

S

TUDY

alert. Fort Marion continued to serve as a storehouse for weapons, supplies, and provisions for

the army during this period.

43

The fort also served briefly as a prison for captured Seminole warriors. King Philip,

Coacoochee, Blue Snake, Osceola, and Coa Hadjo were among the Indian leaders captured by

American troops during the fall of 1837. Their loss weakened Seminole resistance, but the

dramatic escape of Coacoochee and nineteen others from the fortress prison in November

brought renewed vigor to the fight. Many of the prisoners who did not escape, including

Osceola, were later sent to Fort Moultrie in South Carolina for safekeeping.

44

As the war progressed, the conflict moved farther south into the Everglades, but the

superior strength of the Americans ultimately proved too much for the natives. In 1842, the

Seminoles conceded defeat and loaded their belongings onto ships headed for their new homes

west of the Mississippi. Approximately 4,000 Seminole Indians were either killed in the fighting

or moved west at the conclusion of the war, leaving few Native Americans in Florida. The

victory brought peace to Florida at a substantial cost: the Second Seminole War was the most

expensive of the Indian wars, costing approximately $20 million dollars and 2,000 American

lives.

45

FORT MARION AS A COASTAL FORTIFICATION

Engineers and officials in the War Department did not view Fort Marion as essential to national

defense prior to the Second Seminole War. Military engineers considered the fort a solid,

defensible work, but they also believed the bastioned

design of the fortress outdated. War Department

officials observed that St. Augustine did not hold a

position of strategic significance in Florida: the

territorial capital moved to Tallahassee in 1824, and

large ships found Matanzas Bay difficult to access.

As a result, the War Department made few efforts to

improve the fortress in the early years of occupation.

Local citizens protested the Army’s neglect in 1832,

Figure 11. View of seawall from south, 1991

petitioning Congress to appropriate funds for repair

43

Sidney Walter Martin, Florida During the Territorial Days (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press,

1944), 183.

44

Mahon, 212-24.

45

Ibid., 238; Albert Manucy, “Some Military Affairs in Territorial Florida,” Florida Historical Quarterly 25:2

(Oct. 1946), 210.

T

HE

U

NITED

S

TATES

W

AR

D

EPARTMENT AT

F

ORT

M

ARION

, 1821-1933

27

Figure 12. View of hot shot furnace from south,

Figure 13. View of water battery from south,

1995

1991

of the fort and reconstruction of the city’s seawall. Congress allocated $20,000 the same year

to make needed repairs to the structures.

46

The seawall received top priority in the expenditure of funds because of a breach which

threatened property and lives in town. The Army Corps of Engineers directed the

reconstruction of the seawall over a period of fourteen years. The outbreak of the Second

Seminole War forced the government to reevaluate the importance of Fort Marion within the

coastal defense system, and additional expenditures for construction of a water battery were

approved in 1842. Workers filled the moat between the east curtain wall and the seawall,

building gun emplacements on the battery terreplein. They also built a hot shot furnace, which

was used to heat iron cannon balls for firing at flammable targets like wooden ships.

47

The completion of the water battery and hot shot furnace in 1844 ended construction

projects at Fort Marion. The fort’s defenses were updated sufficiently to be included as part of

the nation’s coastal defense system. Like many of the contemporary fortifications along the

American coastline, however, the fort lacked one ingredient key to its defense: a garrison to

man its guns. When Confederate troops came to take over Fort Marion in 1861, they found

only one elderly caretaker occupying the fortress.

48

FLORIDA IN THE CIVIL WAR, 1861-1865

At the conclusion of the Second Seminole War in 1842, Florida began a gradual return to a

peacetime economy. Farmers returned to their fields, and merchants resumed trade. Soldiers

stationed in St. Augustine during the war were relocated to other posts around the country.

Migration into the territory from the north continued, so that by 1845 Florida had sufficient

46

Bearss, 35, 46-8.

47

Bearss, 152-230: Albert Manucy, Artillery Through the Ages (Washington: National Park Service, 1949,

reprint 1985), 69.

48

Arana, et al., 18-19

28

C

ASTILLO DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

N

ATIONAL

M

ONUMENT

: HI

STORIC

R

ESOURCE

S

TUDY

population to apply for statehood.

49

Congress accepted Iowa and Florida into statehood

simultaneously, maintaining the balance between free and slave states in the Union. The need

for such compromise illustrated the growing tension between the slave states of the South and

the free states of the North, a tension that led to the secession of South Carolina in late 1860.

On January 10, 1861, Florida followed suit and the next month became part of the newly

formed Confederate States of America.

50

Throughout the South, secession governors ordered state troops to seize federally owned

forts. In Florida, the governor sent state troops into Fort Marion, Fort Clinch, Fort Barrancas,

and the Chattahoochee Arsenal five days before the formal act of secession by the legislature.

Troops entered Fort Marion on January 7 and took the fortress from its solitary caretaker

to Confederate forces, and the siege on the fort in April 1861 signalled the beginning of the Civil

War.

51

Florida contributed minimally to the war effort, both because of its limited supply of men

and provisions and its location far south of the major theaters of the war. In St. Augustine,

troops dismantled the guns at Fort Marion and shipped them to positions more important to the

defense of the South. When Union gunboats appeared outside the harbor in March 1862,

Confederate forces quickly departed the city; federal troops occupied St. Augustine on March

11 without confrontation. The Union forces upgraded Fort Marion to a state of defense, but

the Confederacy made no attempt to reclaim the city for the duration of the war.

52

The federal occupation of the city continued after the Confederate surrender at

Appomattox; troops assigned to Florida during Reconstruction were headquartered in St.

Augustine. The strain of the war effort and the absence of winter tourists combined to deplete

apparent: the local orange industry was rebounding, tourists were returning, and the first

suburbs began to appear outside the old city walls.

53

FORT MARION AND THE WESTERN INDIAN WARS

As St. Augustine recovered from the Civil War, army engineers once again evaluated the

importance of Fort Marion within the coastal defense system. In 1866, the War Department

49

Buker, 160-72.

50

Bearss, 255: Tindall and Shi, 405.

51

(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1950), 34.

52

Coulter, 398: Bearss, 256-63.

53

Thomas Graham, “The Flagler Era, 1865-1913,” in , The Oldest City: St. Augustine, Saga of Survival, ed.

Jean Parker Waterbury (St. Augustine: St. Augustine Historical Society, 1983), 183-9.

without a fight. At Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, federal troops did not surrender

the town’s resources, and recovery occurred slowly. Yet, by the 1870s, improvement was

Bearss, 255-6: E. Merton Coulter, The Confederate States of America, vol. 7 of A History of the South

T

HE

U

NITED

S

TATES

W

AR

D

EPARTMENT AT

F

ORT

M

ARION

, 1821-1933

29

declared the fort nonessential to the nation’s defenses but worthy of maintenance until further

notice. The garrison stationed in St. Augustine made needed repairs to the fort and prepared

it for possible use as a prison.

54

In the aftermath of the Civil War,

the attention of the federal

government shifted to the Great

Plains, where the march of American

settlers across the continent had

continued virtually unabated

throughout the war. The search for

precious minerals and new

agricultural lands drew miners from

the west and farmers from the east

toward the center of the continent.

This new population of settlers not

only infringed upon Indian lands but

also threatened resources upon

Figure 14. Fort Marion courtyard,

C

. 1870

which the natives relied. While some

tribes agreed to removal to new

reservations, many others resisted, remembering the broken promises of the 1830s that had

originally placed them on reservations. The Western Indian wars began in the early 1860s and

continued through the 1880s.

55

In the course of the Indian campaigns, the army captured a number of rebellious natives for

whom accommodations removed from the scene of battle were needed. Army officials chose

Fort Marion, which had been used as a prison periodically from the time of the American

Revolution, to house some of the captives. Seventy-one members of the Cheyenne, Kiowa,

Comanche, Caddo, and Arapaho tribes arrived at the fort on May 21, 1875. Lt. Richard H.

Pratt, who escorted the Indians to Florida, directed the construction of a wooden shed on the

terreplein to house the prisoners.

56

Pratt attempted to educate and assimilate the Indians during the three years they were at

Fort Marion, teaching them vocational skills as well as arithmetic, history, and English. He also

encouraged them to make souvenirs to sell to tourists for spending money. When the prisoners

were released by the War Department in 1878 to return home, a group of young men went to

the Hampton Institute in Virginia to further their education and assimilation. Pratt’s experience

54

Bearss, 262.

55

Tindall and Shi, 478-82.

56

Bearss, 275-80.

30

C

ASTILLO DE

S

AN

M

ARCOS

N

ATIONAL

M

ONUMENT

: H

ISTORIC

R

ESOURCE

S

TUDY

with the Native American captives at Fort Marion led him to establish the Carlisle Indian

Training School in Pennsylvania in 1880.

57

Conflicts with the western tribes continued into the 1880s. In April 1886, a new group of

prisoners arrived in St. Augustine from Arizona. The seventy-seven Apaches had surrendered

to the army and were sent to Florida while the rest of the tribe was still at large. The Indians

lived in army tents on the parade ground of the fort. By January 1887, the total number of

prisoners at the fort was 447. As with the group that preceded them, the Apaches were

educated in a special school, and tourists frequented the fort for a view of the men, women, and

children. After a year of captivity in Florida, the prisoners were shipped to a reservation in

Oklahoma.

58

Figure 15. Native American prisoners at Fort Marion, date unknown

Albert Manucy, Rhoda Emma Neel, and F. Hilton Crowe (National Park Service, 1939), 5-7.

58

Omega G. East, Apache Prisoners in Fort Marion, 1886-1887 (National Park Service, 1951).

57

Albert Manucy, “Indian School at Fort Marion,” chap. 16 in Great Men and Great Events in St. Augustine,

T

HE

U

NITED

S

TATES

W

AR

D

EPARTMENT AT

F

ORT

MARI0N, 1821-1933

31

FORT MARION NATIONAL MONUMENT

St. Augustine was a popular tourist destination as early as 1830, attracting many northerners

with its healthful climate and unique history. The tourism industry continued to grow until the

Civil War, when travel between North and South became impossible. Recovery was slow after