[319]

II

TEFF

“Survey on the nutritional and health

aspects of teff (Eragrostis Tef)”

Client

Dr. Arnold Dijkstra

Hogeschool van Hall-Larenstein

Lector Food safety

T: 058 2846160

E: arnold.dijkstra@wur.nl

Teachers

Ing. Joyce Polman

Hogeschool van Hall-Larenstein

Teacher foodmicrobiology, chemistry and biochemistry

T: 0317 486284

E: joyce.polman@wur.nl

Dr. Arnold van Wulfften-Palthe

Hogeschool van Hall-Larenstein

Teacher

E: arnold.vanwulfftenp[email protected]

Authors

Dr. Patricia Arguedas Gamboa

Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica, Sede Central

Apdo. 159-7050 Cartago. Costa Rica

T: 00(506) 2550-2695

E: parguedas@itcr.ac.cr

Lisette van Ekris

Hogeschool van Hall-Larenstein

Student Food science and technology

E: lisettevanekris@wur.nl

[320]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

III

Summary

Teff is an interesting grain used for centuries as the principal ingredient of the Ethiopian

population diet. The principal meal in which teff is used is called enjera: a big flat bread or

pancake, than is eaten alone or with any kind of meats, vegetables and sauces. Teff is the

smaller grain ever known, and even that it has been demonstrated that it was used by

Egyptian Pharaohs; it is until two decades ago that it became the issue of agronomic,

nutritional, food technological, microbiological, chemical and physical research. Teff can be

used too in all kind of bakery products, beverages, sauces ingredient and porridges. This

grain is used too as a livestock.

The potential of this grain as an interesting raw material to new food products development is

due principally to its protein composition: it is gluten free and it has a very high quality of

amino acid composition. It is compared with egg protein and with an ideal protein for children

between two and five years old. A lot of scientific people have been demonstrated that teff

starch has a low glycemic acid, and that it has a mineral composition better than this or other

cereals.

That’s why, this microscopic grain is beginning a big war between different grain producers

and processors. Some companies want to demonstrate that human been needs to include

teff as an important component of his diet. This is against the economical interests of other

big companies and associations, as this that grow, harvest, mill, process and storage wheat

flour.

This work pretend to collect the different information generated about teff grain, in an

objective way, and that can help governments, nutritional, agronomic, and food processing

institutions to better target their research about this topic.

The authors made a brief description of the grain from an agronomical and genetically point

of view. They go deeply in the chemical, physical and microbiological characterisation.

In the macro-chemical composition, this grain offers big possibilities to their processing. The

starch can be modified with chemical procedures, in order to change its physical

characteristics, which made this raw material useful to different technological applications.

In the micro-chemical composition, that is very important to define the nutritional value of a

food, the authors of this work found a lot of contradictions between different articles and

different writers. This made of teff a polemic grain.

The microbiological composition of teff, enjera, and ersho is widely different, according with

the region, the fermentation step and the teff variety used. However, it is demonstrated than

the fermentation step is very important from a nutritional point of view: The relationships

phytate:iron, Tannin:iron, phytate:zinc and tannin:zinc decrease. This increase the availability

of minerals, to be used by human enzymes.

At the last chapter; Medical aspects and teff benefits, the reader can find a little description of

diseases in which teff can help to decrease their incidence or their symptoms (celiac,

annemia, osteoporosis, diabetes and obesity). In almost all the cases, the information found

at the literature it´s not enough to obtain trusty conclusions about the benefits obtained by

patients if they include teff as a normal ingredient of their diet.

Finally, the authors finish with the proposal to elaborate and interdisciplinary and

intersectional big project, in order to know the true, and to define standardized methods to

produce, harvest, processing and storage teff, enjera and other teff products.

[321]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

1

1 Te ff

1.1 Introduction

Teff (Eragrostis Tef) is an intriguing grain, ancient, minute in size, and packed with nutrition.

Teff is believed to have originated in Ethiopia between 4000 and 1000 before Christ (BC).

Nowadays, teff represents the re-discovery of a crop used by ancient civilizations

(Stallknecht, 1993).

It is possible to speak of a re-discovery, because nowadays, there are new techniques to

analyze and well know the chemistry and physical characteristics of crops. In addition to that,

new methods to collect and analyze these data have been developed, leading us to

understand that our ancestor had valuable information about their crop benefits, meanly

about teff.

Recently, a lot of scientists of developing countries, trying to offer new products for

consumers, and trying to satisfy their nutritional needs, they were wondered about the lack of

anemia, osteoporosis, celiac disease and diabetes in the Ethiopia population. It is also well

known, in a worldwide level, that the resistance and general good fitness of Ethiopian sport

people is very good. That’s why new scientists are interested to know all about the teff

composition, the nutritional properties, and the changes that happens at the moment of grain

fermentation, during the preparation of enjera, a flat bread that is responsible for about 70 %

of the Ethiopian population. This research has been done by universities from Ethiopia and

other countries, and also privates companies are working with this crop to make it a ¨golden

grain¨.

Teff seeds were discovered in a pyramid thought to date back to 3359 BC. In contrast to

amaranth, another little grain which was utilized by early civilizations throughout the world,

the grain has been widely cultivated and used only in Ethiopia, India and it's colonies and

Australia (Railey,). Teff is grown primarily as a cereal crop in Ethiopia.

The word teff is thought to have been derived from the Amharic word teffa which means

"lost," due to small size of the grain and how easily it is lost if dropped. It is the smallest grain

in the world, ranging from 1–1,7mm long and 0,6–1mm diameter with l000 seed weight

averaging 0,3–0,4 grams and taking 150 grains to weigh as much as one grain of wheat. The

common English names for teff are teff, love grass, and annual bunch grass. It is

intermediate between a tropical and temperate grass.

[322]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

2

The colour of the Teff grains can be ivory, light tan to

deep brown or dark reddish brown purple, depending on

the variety. Teff has a mild, nutty, and a slight molasses

like sweetness. The white teff has a chestnut-like flavor

and the darker varieties are earthier and taste more like

hazelnuts. The grain is somewhat mucilaginous. It is

interesting that documents dated from the late 1800's

indicate the upper class consumed the lighter grains, the

dark grain was the food of soldiers and servants. The

cattle consumed hay made from teff (Railey).

It is then, an interesting activity for scientific people like

nutritionists, chemists, food engineers and for trade

people, to re-discover this attractive little grain that is

really ancient but new for developing countries. It is of a

very small size but with a giant nutritional content.

Figure 1.1, Teff. From

http://images.google.nl/images?hl=en&q=teff&btnG=Search+Images&gbv=2

1.2 Agronomy and taxonomy aspects

Eragrostis is a member of the tribe Eragrosteae, sub-family Eragrostoidae, of the Poaceae

(Gramineae). Teff is a tetraploid plant 2n = 40. (Stallknecht, 1997).

There are approximately 350 species in the genus Eragrostis consisting of both annuals and

perennials which are found over a wide geographic range. Eragrostis teff is one of those

species. The closest relative of teff is E.Pilosa (Yu, 2006). Eragrostis species are classified

based on characteristics of culms, spike lets, lateral veins, pedicels, panicle, flowering

scales, and flower scale colours. Recently, the taxonomy of teff has been clarified by

numerical taxonomy techniques, cytology and biochemistry, including leaf flavanoids and

seed protein electrophoretic patterns (Jones et al. 1979; Costanza et al. 1980; Bekele and

Lester 1981).

Teff is a fine stemmed, tufted annual grass characterized by a large crown, many shoots,

and a shallow fibrous diverse root system. The plants germinate quickly and are adapted to

environments ranging from drought stress to water logged soil conditions. The inflorescence

is an open panicle and produces small seeds (1.000 weigh 0,3 to 0,4 g). The florets consist

of a lemma, 3 stamens, two stigma and two lodicules. Floret colours vary from white to dark

brown. Plant height of teff varies from 25–135 cm which dependents on cultivar type and

growing environments. Panicle length 11–63 cm, with spike lets numbers per panicle varying

from 190–1410. Panicle types vary from loose, lax, compact, multiple branching multi-lateral

and unilateral loose to compact forms. Maturity varies from 93–130 days (Stallknect, 1999).

Teff is an annual warm season grass crop (Stallknecht, 1997). Teff is a self pollinating

chasmogamous plant. It is a reliable low risk crop, and can be planted in late May similar to

millets. Late plantings have the advantage to control emerged weeds by tillage prior to

planting, which can be significant since teff is a poor competitor with weeds during the early

growth stages. Planting of teff requires a firm moist seed bed, similar to planting for alfalfa.

To affect good soil moisture-seed contact due to the extremely small seed size. Seeding

rates varies from 2.3 to 9 kg/ha, with 5 to 8 kg/ha generally recommended (Twidwell et al,

1991). Teff should be seeded 12–15 mm deep either broadcast or in narrow rows

(Stallknecht, 1997). Control of broadleaf weeds should be considered, particularly

Amaranthus retroflexus redroot pigweed, which produces seed that cannot be separated

from teff. Moderate rates of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer are suggested to prevent

[323]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

3

lodging. Several special considerations must be given to teff harvested for grain. Due to the

small seed size, combine seed delivery systems must be checked for gaps and areas

through which the small teff seed can be lost. Soil particles must be prevented from going

through the combine and into the grain hopper, since it is very difficult if not impossible to

separate fine soil particles from the teff grain. Teff germinates rapidly, and the broadcast and

narrow row seeding allow for stronger weed competition (Stallknecht, 1997). Teff is adapted

to environments ranging from drought stress to water logged soil conditions. Maximum teff

production occurs at altitudes of 1800–2100 m, growing season rainfall of 450–550 mm, with

a temperature range of 10–27°C. Teff grain yields in the U.S. average from 700 kg/ha dry

land to 1400 kg/ha irrigated in Montana (Eckhoff et al. 1993; Stallknecht et al. 1993). Forage

yields vary from 9.0 to 13.5 Mg/ha, dependent upon moisture levels during the growing

season (Boe et al. 1986; Eckhoff et al. 1993). Teff is day length sensitive and flowers best

during 12 hours of daylight.

While teff grain still provides over two-thirds of the human nutrition in Ethiopia, occupying two

million hectares in 2003–2004 (Yu, 2006), representing 20% (2 8 106 t) of the total cereal

production of the total cereal production of the country (CSA, 1997). It is relatively unknown

as a food crop elsewhere. Teff has adaptive characteristics similar to other crops grown by

early civilizations. Teff can be cultivated under a wide range of environmental conditions

even on marginal soils under water logged to drought conditions. Teff can produce a crop in

a relative short growing season and will produce both grain for human food and fodder for

cattle (Stallknecht, 1993).

Planting can be accomplished using a Brillion grass seeder and cultipacker combination, or

by a spinner type grass seeder. Teff germinates rapidly when planted an average depth of

1,2 cm, however, the initial growth is slow until a good root system has been established.

Forage yields of teff in South Dakota have ranged from 4 to 11 t/ha depending upon planting

date and number of cuttings (Boe et al. 1986). In Montana, forage yields cut from dry land

and irrigated cropping ranged from 2.2 to 15 t/ha. Teff seed yields in Montana ranged from

0.2 to 1.5 t/ha. The low seed yields were obtained at the MSU Southern Agr. Res. Center,

Huntley, when planted as a non-irrigated dry land crop, due to poor stands and drought

conditions. Harvesting teff for either forage or seed production is easily accomplished, as

long as the combine is seed tight. Teff seed can shatter if harvest is delayed. Broad leafed

weeds in teff can be easily controlled by use of broad leaf herbicides, however grass weeds

if present, can out compete the teff during the early stages of plant growth. Now specific

fertility studies have been conducted, but rates similar to those suggested for millets or

sorghums are recommended. Green house studies on nutritional requirements of teff have

been conducted at Oklahoma State University Department of Agronomy, Stillwater (pers.

commun.).

Inadequate nutrient and organic-matter supply constitutes the principal cause for declining

soil fertility and productivity in much of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Increasing food production

and sustaining soil fertility on the smallholder farms is an enormous challenge in the SSA.

Soil nutrient status is widely constrained by the limited use of inorganic and organic fertilizers

and by nutrient loss mainly due to erosion and leaching (Tulema et al, 2005). Many small

holder farmers do not have access to synthetic fertilizer because of high price of fertilizers,

lack of credit facilities, poor distribution, and other socio-economic factors. Consequently,

crop yields are low, in fact decreasing in many areas, and the sustainability of the current

farming system is at risk (Stangel, 1995; UNDP, 1992). Ethiopia is one of the 14 sub-

Saharan countries with highest rates of nutrient depletion (Stoorvogel and Smaling, 1990)

due to lack of adequate synthetic-fertilizer input, limited return of organic residues and

manure, and high biomass removal, erosion, and leaching rates. The annual nutrient deficit

is estimated at 41 kg N, 6 kg P, and 26 kg K per ha per year (Stoorvogel and Smaling, 1990).

There is an urgent need to improve nutrient management.

[324]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

4

In the other hand, in a survey in Gare Arera, the central Ethiopian highland, farm yard

manure (FYM) and compost, enriched with ash, were identified as underutilized organic

nutrient sources. Mustard meal, a by product of mustard-seed oil production, is also locally

available. That’s why the Ethiopian researchers, as Tulema et al, are working with the

purpose to find the way to increase, with local and not expensive resources, the quality of

their country lands. FYM is a potential source of organic fertilizer as the country has the

highest livestock number in Africa. The annual dry-manure production is estimated at 22,7

million Mg. Annual crop-residue production is estimated at 12,7 million Mg. Moreover, there

are various other unexploited organic by-products or wastes from processing animal and

plant products such as mustard meal, coffee husk, sugar cane straw, and abattoir by-

products. Use of FYM and other locally available organic materials is important for improving

soil quality.

Tulema et al, they found that farmers did not utilize FYM efficiently due to lack of confidence

in the effect of FYM, labour shortage for FYM management, and weed problems. The

distance between croplands and homesteads (kraal location) was another important

constraint as the fields were scattered over a large area in the watershed. Previous studies

have also suggested the distance of fields from kraal as a major problem in FYM utilization

(Hailu et al, 1992; Dereje et al, 2001). The writers appointed too, that compost could be an

important organic fertilizer that all farmers produce and use, as materials such as household

wastes, ash from burnt biomass, and water were available for composting.

Tulema et al concluded that the effects of organic fertilizers on teff partly exceeded the

effects of equivalent amounts of N given as urea together with triple super phosphate. The

investigation showed that available organic resources in Gare Arera are underutilized for

lowing down soil nutrient depletion and for improving the productivity. However, continued

on-farm experimentation with farmers’ participation is important in order to evaluate the

technical and economic efficiencies under different ecological conditions.

Mixed cropping is often superior to sole cropping in terms of insurance against risk, efficient

use of resources and higher net returns. Most successful mixtures have been of a legume

and non-legume, and there are few reports of yield increases from non-legume mixtures.

Bayu et al. mixed cropping of teff and sunflower under the semi-arid conditions of north-

eastern Ethiopia. They found that Intercropping teff and sunflower in semi-arid areas of Welo,

Ethiopia has yield advantages over monoculture yields as the resource utilization is

complementary. In intercrops the component crops can exploit different soil horizons,

whereas a sole crop has its own specific rooting horizon.

Diseases and Pests

Teff is relatively free of plant diseases when compared to other cereal crops. In Ethiopia, in

locales where humidity’s are high, rusts and head smuts are important diseases. In Ethiopia,

22 fungi and 3 pathogenic nematodes have been identified on teff (Bekele 1985). Teff

seedlings are also susceptible to Damping-off caused by Drechslera poae and

Helminthosporium poae (Baudys) Shoemaker, when sown too early (Ketema 1987). Insect

pests of teff in Ethiopia are Wello-bush cricket, Decticoides brevipennis, red teffworm,

Mentaxya ignicollis, teff epilachna, and teff black beetle. Since teff has been limited to small

areas in the United States a few disease and insect problems have been observed.

However, a serious problem was observed in South Dakota where the stem boring wasp,

Eurytomocharis eragrostidis (Howard) reduced forage yields by over 70% (McDaniel and

Boe 1990). Although the insect problem was observed in only one out of the five years in

research trials, the significant losses obtained could be a deterrent to commercial expansion

of teff production.

Cultivars

[325]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

5

Develop methods to improve the breeding of teff

cultivars (which are self-pollinating) there have

only met limited success (Mengesha et al. 1965;

Berhe and Miller 1978; Berhe et al. 1989). While

teff production in Ethiopia occupies large areas

and is the most important staple of the country,

most cultivars are selections that have been

grown for thousands of years. Although cultivar

development has been given a high research

priority most on going studies have focused on

agronomic practices.

Today, Ethiopia is assumed to refuge about 6500

to 7000 higher plant species of which 12% are

endemic (exist only in Ethiopia) and over 1400

wild vertebrate (not considering domesticated

ones) species which 85 of them are reported to be

endemic. Yet the country is believed to be highly

endowed with smaller flora and fauna including

microbial species. Ethiopia does not only have

high species diversity but also high genetic

diversity with in a species which obviously is

attributable to its diverse ecosystems and

historical intervention of its people (Sertse, 2008).

Figure 1.2, Growing teff. From

http://images.google.nl/images?hl=en&q=teff&btnG=Search+Images&gbv=2

[326]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

6

1.3 Genetic characterisation

Teff belongs to the family Poaceae, sub-family Eragrostidae and genus Eragrostis. This

genus has 350 species and it is the only cultivated cereal species. The teff center of origin

and diversity is Ethiopia (Bay et al, 2000, Yu et al 2006, Yu et al, 2007).

Some cultivars have been identified using phenotypic characteristics, such as: plant size,

maturity, seed colour, panicle form. As a result of using these characters for cultivar

identification, a large variation has been observed. This variation can be explained because

morphological characters are susceptible to environment. New biotechnology tools have

been developed for cultivar identification. Molecular markers have been used to study

genetic variation and the relationship within and amount species. These new techniques are

not affected by phenotypic nor by the environment (Bay et al, 2000).

Bay et al, 2000 set up a study

to evaluate genetic diversity

of teff and its relatives. Forty

seven accessions of E. teff,

some of them were describe

according to agronomic and

morphological traits, three

accessions from E. pilosa

and six accessions from E,

curvula. Two accessions

from E. curvula came from

United States and another

two from Argentina. The

molecular marker used in this

Figure 1.3, Teff seeds. From

www.hort.purdue.edu/.../eragrostis_tef_nex.html

work was Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD). This molecular marker has been

used in many other crops to study the genetic relationships among species and cultivars.

According to the results, the genetic distance between teff accessions was between 0,84 and

0,96, indicating high similarity or low polymorphism at the DNA level (Figure 1.4). Therefore,

teff has a narrow genetic base and a few genes could control the morphological variations

showed by teff germoplasm. When they studied the genetic relationship between teff and

wild species, a higher polymorphism was found between the three species. The genetic

distance between them was from 0,18 to 0,88 (Fig. 1.5), which indicates the high degree of

genetic diversity. As a result, the three species were classified into two main groups. E. teff

and E pilosa were in one group because they had a higher polymorphism, and E. curvula

was in another group. Also, other researchers had concluded that the closest relative to E.

teff was E. pilosa (Yu et al, 2006 and Yu et al, 2007). These two species could cross and

new genes from the wild relative could be transferred to E. teff, providing new genetic

resources for teff improvement (Bay et al 2000 and Yu et al 2006). Another result from Bay

et al, 2000´s study was the higher genetic distance between accessions from E. curvcula.

Those accessions collected from Ethiopia were closed related (86%), but they were distant

from those from United States and Argentina (Bay et al, 2000). Even though, E. teff has a

very narrow genetic variation, it could be increased by wild relatives, mainly E pilosa, which

E. teff could be crossed. However, E. curvula has the higher genetic distance and it could be

a source of genes that could be introduce to E. teff by biotechnology tools.

[327]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

7

Figure 1.4, Diagram of teff accessions (accessions name given next to its corresponding

branch (Bay et al, 2000))

[328]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

8

Figure 1.5, Diagram of E. teff and other Eragrostis species (Bay et al, 2000)

[329]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

9

2 Products

2.1 The uses of teff

The principal use of teff grain for human food is the Ethiopian bread (enjera). It is used to

wrap all kind of foods. This is an easy way to eat them, without fork or spoon, and the

nutritional level of the meal increases (www.globalnomad.net/pages/enjera.jpg). Teff is

ground into flour, fermented for three days then made into enjera. Enjera is a sourdough type

flat bread. It is described as a soft,

porous, thin pancake, which has a sour

taste. Teff is free in gluten and therefore,

the bread remains quite flat. When eaten

in Ethiopia, teff flour is often mixed with

other cereal flours, but the flavour and

quality of enjera made from mixtures is

considered less tasty. Enjera made

entirely from barley, wheat, maize or

millet flours is said to have a bitter taste.

The degree of sour taste is imparted by

the length of the fermentation process. If

the dough is fermented for only a short

period of time (no more than ten days),

Figure 2.1, Enjera with vegetables sauce. From fooditudeblog.blogspot.com/

enjera has a tasty sweet flavour. Research studies on the techniques used to make enjera

have indicated that the yeast, Candida guilliermondii (Cast.), is the micro-organism primarily

responsible for the fermentation process (Stewart and Getachew 1962). Enjera is a major

food staple, and provides approximately two-thirds of the diet in Ethiopia (Stewart and

Getachew 1962). It is also eaten as porridge and used as an ingredient of home-brewed

alcoholic drinks. Teff is a very versatile grain. Teff flour can be used as a substitute for part of

the flour in baked goods, or the grains added uncooked or substituted for part of the seeds,

nuts, or other small grains.. It is a good thickener for soups, stews, gravies, and puddings

and can also be used in stir-fry dishes, and casserole dishes. Teff may be added to soups or

stews in either of two ways:

1) Add them, uncooked to the pot a half-hour before serving time.

2) Add them cooked to the pot 10 minutes before serving.

Cooked teff can be mixed with herbs, seeds, beans or tofu, garlic, and onions to make grain

burgers. The seeds can also be sprouted and the sprouts used in salads and on sandwiches.

Teff flour is also used for making traditional alcoholic drinks like tella (local opaque beer) and

katikalla (local spirit), kitta (sweet dry unleavened bread), muk (gruel)(Bultosa et al, 2002).

Teff has been used by Yigzaw et al, to be mixture with Grass pea (Lathyrus sativus). This is

one of the important food legumes in countries like Bangladesh, India and Ethiopia. It has

desirable agronomic in intercrops the component crops can exploit different soil horizons,

whereas a sole crop has its own specific rooting horizon. Another example of mixed cropping

with teff, is the case of sunflower, that we talked about in the Agronomy section. Putnam et

Allan, 1992, indicate that differences of maturity between both crops, to make better use of

light.

[330]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

10

Fermentation of cereals or their blend

with legumes is a potentially important

processing method that can be expected

to improve the nutritive value such as

availability of proteins and amino acid

profile. It could also decrease certain anti

nutritional factors like phytates, protease

inhibitors and flatulence factors.

Although mixing teff with grass pea has

not been part of the traditional practice for

food preparation in Ethiopia, exploring the

potential of fermentation of their blend

may be beneficial. One obvious reason is

developing an affordable nourishing crop

for the poorer section of the population.

Yigzaw et al. did not want to go higher

Figure 2.2, Enjera with vegetables and meat. From www.dkimages.com/.../Ethiopia/Ethiopia-

19.html

than 8:2 (teff: grass pea) ratio as a compromise between nutritional adequacy and sensory

value.

Teff is also produced in other countries. Countries such as USA, Canada, Australia, South

Africa, and Kenya have produced teff for different purposes such as a forage crop and a

thickener for soups, stews, and gravies (Zedwu, 2007).

Teff has also a lot of fanatic consumers, like the top Ethiopians sportsmen Haile Gebrelassie

and Kenisse Bekele (Turkensteen, 2008), they say that the teff products are not only gluten

free but might help consumers to control their weight. Different then the modern grains teff

helps the body to be fit for life. They think that products made out of teff, including enjera,

helps them break international records over and over again.

This is possible because teff has a high content of iron. This made that the haemoglobin in

the blood is higher, so more oxygen can be transmitted, and the sportsmen can reach better

sport results.

In the first page of the Soil & Crop Company Website, there can be found the following

phrases that enhance people to consume teff. “A grain as healthy as nature itself. Loaded

with all compounds which are necessary for our body. Healthy food for everyone. Is

teff made for our body or is our body made for teff?”

Even Soil & Crop say: “Eragrain teff (they call teff Eragrain teff) is a wholegrain cereal. A

valuable grain, loaded with good food compounds (http://www.soilandcrop.com

/index.php?lang=eng). A grain so valuable that 55 centuries ago, teff was placed in the

pyramids together with pharao's as food for their last journey. People in Ethiopia have always

been loyal to their teff. They eat teff at every meal. Because teff is so nutritious, people in

Ethiopia hardly suffer from such diseases as anemia, osteoporosis and diabetes. Scientist

does connect this to the consumption of teff. Compared to wheat, barley and oats, Eragrain

teff has a high content of minerals such as: iron, calcium, zinc and magnesium”.

Teff has been used to increase the quality of enjera made with tannin-containing sorghums.

In a research made by Yetneberk et al, 2005, enjera was produced with a 50:50 (w/w)

composite of whole tannin-containing sorghum and teff. This process reduced the tannin

[331]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

11

content of the flours, which appeared to relieve the inhibiting effects of tannins on the

fermentation (Yetneberk et al, 2005).

Teff is used a lot for livestock feeding in Ethiopia and other countries. It is complemented

with other crops, in order to increase nutritive value. Mengistu et al. studied supplementing

the teff (Eragrostis teff) straw feed of Arsi oxen (Bos indicus) with noug (Guizotia abyssinica)

meal. Supplementation significantly increased feed intake, average daily gain, and the weight

of dressed carcass and lean meat. Supplementation with 1 kg of noug meal was the most

profit table, giving a net return per animal of US$17.10, whereas a sole diet of teff straw gave

a loss of US$18.66 per animal (Mengistu et al, 2007)

As said before teff has been used by Yigzaw et al, to be mixtured with Grass pea (Lathyrus

sativus). In their experiments, they found that the fungal fermentation improved the amino

acid profile for the essential amino acids in all the mixtures grass pea:teff. Fermentation of

teff:grass pea (8:2) , in particular has been found to be quite comparable in essential amino

acid profile to an ideal reference protein recommended for children of 2 – 5 years old.

Finally, teff is used as a component in adobe construction in Ethiopia.

Figure 2.3, Baking of enjera. From www.fao.org/.../compend/img/ch16/ph02509.htm

[332]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

12

2.2 Teff products

As teff is a cereal, it is possible to develop with it, the same products than with other cereals.

It is not only for human consumption, but also as feed for animals. In a first step, the seed is

milled to obtain flour. As it will be exposed in the Chemical Characterisation chapter, teff has

no gluten proteins. This made this flour very interesting to be used in gluten-free-diets. But, in

the other hand, this decrease the sensory quality of baked products made from teff.

The food alternatives for Celiac Disease patients are mostly based on maize, rice, and soy.

Teff appears to be another interesting possibility. In wheat bread dough the gluten proteins

naturally form a viscoelastic network required for the desired functional properties of bread

products (Hooseney, 1986). Because these kinds of proteins are lacking (or in insufficient

quantity) in maize and rice, the gluten-free breads lack good quality properties. Therefore, to

improve the functional properties of gluten-free bread, the dough could be treated with

microbial transglutaminase (mTG), which cross-links proteins and improves functionality

(Moore et al, 2006). In general, gluten-free breads treated with mTG tend to have a better

overall quality due to the formation of a stable protein network. The authors of this work think

that the same can be applied to teff, and in this manner, it will be possible to obtain high

quality baked products.

However, teff can be used to elaborate the following products, and it is possible to find any

kind of recipes. (http://www.bobsredmill.com/recipe/ingredient.php?pid=386)

Appetizers

Baked goods

Biscuits and scones

Breads

Breakfast and desserts bars

Breakfast dishes (to be eaten with fruits and milk, hot or cold)

Brownies

Cakes and cupcakes

Casserole dishes

Cookies

Crackers

Desserts

Dips, sauces and gravy

Granolas (muesli)

Muffins

Pancakes & waffles

Pastas

Pie crusts

Pizza crusts

Rolls & buns

Soups & stews

Tortillas and flat breads

Figure 2.4, Teff bread mix. From

Railey.

There can be conclude that with the nowadays technology every product that normally is

made from wheat can be made with teff. There is not found a product that can be made from

wheat and not from teff.

[333]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

13

3 Characterisation of teff

Even if some companies and writers are enhancing the composition of teff as a way to

accomplish its re-discovery, teff chemical composition is not far of this of other cereals, even

from a macro component as from a micro components point of view. Bultosa et al, 2002, they

say about that: The micro- and macronutrients level of grain teff is apparently higher than

that of barley, wheat and sorghum. The nutrient composition of grain teff indicates that it has

good potential to be used in foods and beverages worldwide (Bultosa el al, 2002). The amino

acid composition of grain teff is reported to be comparable to that of egg protein, except for

its lower lysine content.

To made a difference between chemical and physical characterisation begin sometimes a

hard work because they are extremely related. The relation between amylose and

amylopectin, define some physical characteristics, as temperature gelatinization, gelation

characteristics, solubility and starch resistance. Thus, the small variations in the amylose

content among teff varieties may influence also the starches to have slightly different

properties.

Using different chemical substances as NaCl, EtOH, NaHCO

3

and CaCO

3

it is possible to

change the medium and as a consequence, physical teff starch properties as foaming

capacity and protein solubility will change.

3.1 Chemical

3.1.1. Macro components

The concentration, relationship and rates between the different macro-components are

essential to determine the texture, appearance and physical characteristics of a food. In

relation with this composition, Food Engineers we have to design food products, and to

select machinery, additives, package materials, etc. The shelf life and then, the storage

systems are defined in function of the food macro composition; Protein, fat, ash and

carbohydrate content are given as 9,6%, 2,0%, 2,9% and 73,0%, respectively.

Lipids: teff starches had slightly lower hydrolyzed lipids (mean 8,9 mg/g) than maize starch

(9,9 mg/g). The crude fat (ether extract) content of the teff starches (mean 0,29%) was

relatively low as compared to that of maize starch (0,34%). The crude fat of grain maize is

around 4,45%, higher than that of grain teff which is around 2% (db) (National Research

Council, 1996). Crude fat (petroleum ether extract) consist mostly of non-starch lipids i.e., it

is not endogenous to the starch [20]. The low crude fat content in teff starch is most probably

related to the low crude fat content of the grain. Bultosa found that the teff total starch lipid

was higher than that of pearl millet (5,0 mg/g) and slightly higher than that of rice (7,6 mg/g).

Starch: In the carbohydrate fraction of grain teff, starch is is the largest proportion (Umeta

and Faulks, 1988). After Bultosa, 2002, the mean amylose content of the teff starches varies

from 28,2 to 28,4, depending of the method used for the determination, and on the teff

variety analysed. Belta et al, 2002, they found an amylose content ranges 24,9-31,7 %. The

authors of this work we think that this differences are not important to determine the potential

of teff as an important component of healthy diets. Amylose determination was made with

two different methods. Both methods showed that the amylose content of the teff varieties

studied is typical of normal native cereal starches like maize, sorghum and wheat (BETTA et

al, 2000) with no waxy- or amylo-type starches.

[334]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

14

Figure 3.1, Starch components, amylase and amilopectin

During the teff products processing, and depending on the degree of enzyme (Whistler and

BeMiller, 1997) or acid treatment, starch can be depolymerised to different types of oligo and

mono saccharides (maltodextrins and glucose).

Table 3.1, Composition of starches from teff and maize.

Teff (five varieties mean)

Maize

Ash (%) (db)

0,16 ± 0,04

0,12 ± 0,03

Protein (%) (N *6.25) (db)

0,19 ± 0,13

0,07 ± 0,01

Crude fat (%) (db)

0,29 ± 0,03

0,34 ± 0,01

Amylose (%)

28,4 ± 2,8

29,5 ± 2,1

Protein: Teff starches had protein contents in the range of 0,16 – 0,23%. Watson, 1998, he

found a mean protein content of the teff starches of 0,19%. This is higher than that of maize

starch (0,07%). Watson think that this is probably because in commercial maize starch

extraction, SO2 is used, which breaks disulphide bonds solubilising protein. The protein

content among the teff varieties probably varied depending upon the degree of contamination

of the starch by the proteins of the endosperm.

3.1.2. Micro components

As these components are present in very small quantities in the foods, they don’t determine

their texture or their appearance, but their nutritional value, and its function to help human

[335]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

15

body to accomplish it different functions. Micro-components are enzyme cofactors and then,

they play an important job in the development of metabolism reactions.

The grain of teff has a very big nutritive value, with a grain protein content (10-12%) similar to

other cereals. Besides providing protein and calories, teff is a good source of minerals,

particularly iron. It has a very high calcium content and contains high levels of phosphorus,

copper, aluminium, barium and thiamine (Yigzaw et al, 2001). But the bigger nutritional

importance that teff has, is the lack of gluten in the grain. This made it useful for patients with

the celiac disease.

The teff starches had ash contents in the range of 0,13 – 0,23%. This is a value comparable

to typical cereal starch ash (0,1 – 0,2%) reported by Swinkels, 1985. Phosphorus content is

similar to that of rice starch.

In the nutritional point of view, it is interesting to know the opinion of different groups. We

exposed what a group of researchers from a USA university found, and what Soil & Crop

researchers they exposed.

The nutritive value of teff for livestock fodder is similar to other grasses utilized as hay or

ensiled feeds (Boe et al. 1986; Twidwell et al. 1991). Digestability studies of cell wall

contents suggest that teff has tropical grass characteristics (Morris 1980), protein and

digestability as forage decreases with increased maturity. Protein content of teff forage

produced in South Dakota ranged from a high of 19,5 to a low of 12% as the plant matured.

In Montana, teff hay protein content ranged from 13,7 to 9,6%. Protein level (10 to 12%) of

teff grain is similar to other cereal grains.

Another point of view that is not favourable to teff, is expressed boy Whistler and BeMiller.

The say: teff is used to elaborate a big quantity of foods and beverages. The nutritional

value of these foods can be also negatively affected because of starch staling and the

possible formation of resistant starch type III on starch retrogradation (Whistler and BeMiller,

1997).

In the other hand, in a study made with the fermentation of a grass pea:teff mixture (8:2), to

be used in cattle feed Yigzaw et al, 2001, has been found that de aminoacidic composition of

he result is comparable to an ideal reference protein recommended for children of 2 – 5

years old.

In the following tables, it appears the teff flour (Eragrain is the flour obtained by Soil & Crop

company) vitamin, metal and aminoacid content, and the comparison with the advised daily

intake for a 75 kg human.

Table 3.2, A selection of the vitamins in Eragrain® flour.

VITAMIN

Eragrain content

(mg/100g)

Advised daily amount

for a 75 kg human

(mg)

Available in 150 g of

Eragrain (%)

(B1) Thiamin

0,51

1,0

76%

(B2) Riboflavin

<0,1

1,5

10%

(B3) Niacin

0,80

16

8%

(B6) Pyridoxin

<0,1

3

10%

(C) Ascorbic acid

0,25

70

1%

(M) Folic acid

<0,02

0,4

8%

Source: WHO (1991), Energy & Protein requirements

[336]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

16

Table 3.3, Amino Acids (mg per 100g) in Eragrain® flour

Amino Acids

Wheat

(whole grain)

Eragrain flour

Advised daily

amount for a

Advailable in

150 g

Eragrain flour

www.nutritiondata.com

S&C

Research

human 75 kg

(mg)

Isoleucine

508

441

750

88 %

Leucine

926

924

1050

132 %

Lysine

378

327

900

55 %

Methionine

(S)

212

433

975

100%

Cystine

317

217

Phenylalanine

646

601

1050 (incl.

tyrosine)

156% (incl.

tyrosine)

Threonine

395

449

525

128%

Tryptophane

212

126

263

72%

Valine

618

601

750

120%

Source: WHO (1991), Energy & Protein requirements

Table 3.4, Nutritional content in Eragrain® flour (mg/100g)

Component

Wheat (whole grain)

Eragrain®

flour

Advised daily

amount

Available in

150 gram

www.nutritiondata.com

S&C

Research

for a human

75kg (mg)

Eragrain®

flour

Water (g)

10,3

10,0

Energy (kJ)

1419

1468

Protein (g)

13,7

12,3

75

25%

Fat (g)

1,9

2,1

Starch (g)

60,0

59,8

Fibers (g)

12,2

7,9

30

40%

Calcium (mg)

34

167

900

28%

Iron (mg)

3,9

5,7

12

71%

Magnesium (mg)

138

194

420

69%

Potassium (mg)

405

477

3500

20%

Zinc (mg)

2,9

4,6

15

46%

Copper (mg)

0,4

0,8

1,1

104%

Vitamin C (mg)

0

0,3

70

1%

Phytic acid (mg)

800

393

Source: WHO (1991), Energy & Protein requirements

Additionally, Soil & Crop staff says: Eragrain® teff contains protein with a good ratio of

essential amino acids, but no gluten. People do not need gluten. On the contrary, gluten,

present in nearly all food products on the market nowadays, can trigger certain allergies or

resistance reactions in our body. Eragrain® teff contains vitamin C and a relative low content

of phytic acid, which is the reason why the body can absorb the minerals to a much larger

extent. This is useful to prevent diseases like anemia. Scientific research in Ethiopia has

shown these results. Uptake of calcium is useful to prevent osteoporosis. Other grains than

teff show all this to a much lesser extent.

[337]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

17

3.2 Physical

Physical characteristics of a food are the result of the macro components concentration, their

relationship and their behaviour under different environment conditions.

The teff starch granule is a compound type from which many simpler (2–6 µm in diameter)

polygonal shaped granules are released on milling (Umeta and Parker, 1996). The

compound granule surface is smooth, with no evidence of pores. The small granule size of

teff starch, when compared with maize starch, was considered as one factor responsible for

the considerably lower paste viscosity (peak, breakdown and setback), higher water

absorption index and lower water solubility index than maize starch (Bultosa, 2002).

An anatomical study of teff grain has revealed that it contains compound starch granules

(Umeta and Parker, 1996), similar to those of rice (Juliano, 1984) and amaranthus. The

pericarp of the grain also contains starch granules like in the case of sorghum.

The granule size is thus slightly larger than that of individual amaranthus starch granules,

which are 1–2 μm in diameter and comparable in size to individual rice starch granules,

which are 3–5 μm in diameter. The starch granules in the different teff varieties appeared

morphologically similar to one another. Most of the granules had a number of sides while a

few of them had essentially cubic shape. The sides of the starch granules where other starch

granules packed were well formed. Most protein bodies are located outside of the compound

starch granules (Bultosa et al, 2002). The X-ray analysis of teff starch granule gives an A

type starch diffraction pattern, apparently more amorphous than maize starch but similar to

rice and sorghum starches in crystallinity level. The X-ray diffraction trace of native teff starch

granules indicates some of the amylose forms an inclusion complex with the endogenous

lipids (LPL or FFA).

Figure 3.2, Individual starch granules of teff. Where: pg: polygonal shape starch granules.

Pb: protein bodies and f: fibre. (From Bultosa et al, 2002).

[338]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

18

Figure 3.3, Scanning Electron Micrograph of a teff compound starch granule. Where: sg:

individual starch granule, pb: protein bodies and cw: cellular wall. (From Bultosa et al, 2002).

Pasting properties

This property is very important to know the flour or starch characteristics of a cereal or

starchy product. They are useful to predict the behaviour of the flour in baking and brewing

process, for example. To determine these characteristics, it is necessary to use a Rapid

Visco Analyser, and the main characteristics are:

Ti: Initial swelling temperature. It indicates the minimum temperature required to cook a

starch (Newport Scientific, 1995).

PV: Peak viscosity. It indicates water-holding capacity of the starch. The units used are RVU,

Rapid Viscosity Unitis, equal to cp*10 Peak viscosity can be affected by granule size

(Fortuna et al, 2000), molecular structure of amylopectin (Shibanuma et al, 1996), cross-

linking, starch water concentration, lipids, residual proteins (Li and Yeh, 2001) and RVA

operating conditions (Batey and Curtin, 2000).

BV: Breakdown viscosity. The units are the RVU.

Rst: rate of shear thinning.

HPV: Hot paste viscosity.

CPV: Cold paste viscosity. Cold paste viscosity is related to the ability of the starch paste to

form a gel after cooling. Gelation occurs with junction zone formation (mostly through

hydrogen bonding), re-associating the hydrated and dispersed starch molecules, and can

vary with the botanical sources of the starch, amylose content and formation of amylose-lipid

complexes, amount of water, other ingredients like proteins and temperature of cooling

(Bultosa et al, 2002). High-amylose (linear) starches re-associate more readily than high-

amylopectin (branched) starches.

SBV: Set back viscosity.

WAI: Water absorption index. WAI is related to the amount and swelling degree of this gel

phase. It reflects the extent of association of the molecules within the starch granule (French,

1994).

[339]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

19

WSI: Water solubility index. Water solubility index reflects the strength of the micellar

network within the starch granules (Qian et al, 1998). The leaching of small molecular weight

polysaccharides will increase as the micellar network of the starch granules become weak.

The RVA (Rapid Visco Analyser) pasting curves of teff starches and maize starch are given

in Fig. . The viscosity parameters evaluated are shown in Tab. 3.5

The mean initial swelling temperature (Ti) for teff starches (74,0 °C) was virtually identical to

that of maize starch (74,1 °C) (Tab.3.5), but apparently higher than that of sorghum starch.

The mean peak viscosity (PV) (269 RVU) of the teff starches was considerably lower than for

maize starch (313 RVU). Small granule size was positively correlated with resistance to

swelling, less swelling and less peak viscosity in wheat, potato and maize native starches

(Fortuna et al, 2000) and this may apply to the case of teff starch. Teff starches took longer

time (mean Pt 4,19 min) to reach PV than the maize starch (mean 2,90 min).

Table 3.5, Pasting properties of starch from teff and maize

Parameters

Mean teff varieties

Maize

Ti

74,0 ± 1,1

74,1a ± 0,1

PV (PVU)

269 ± 13

313d ± 2

Pt (min)

4,19 ± 0,62

2,90a ± 0,04

HPV (RVU)

190 ± 13

184b ± 2

BV (RVU)

79 ± 17

129e ± 3

Rst (RVU/MIN)

8,4 ± 1,8

12,2c ± 0,3

CPV (RVU)

292 ± 14

344c ± 4

SBV (RVU)

101 ± 11

161c ± 6

The mean breakdown viscosity (BV) for teff starch pastes (79 RVU) was considerably lower

than that of the maize starch paste (129 RVU). At BV, the swollen granules disrupt further

and amylose molecules will generally leach out into the solution and align in the direction of

the shear (Whistler and BeMiller, 1997).

Figure 3.4, Rapid Visco Analyzer.

From:http://images.google.nl/images?hl=en&q=Rapid+Visco+Analyzer&btnG=Search+Images

&gbv=2

[340]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

20

The rate of shear thinning (Rst) for all the teff starches (mean 8,4 RVU/min) was lower than

that for maize starch (12,2 RVU/min). The degree of Rst is reported to be influenced by the

structural network of starch molecules, morphology and rigidity of the swollen starch granules

(Subramania et al, 1994), and starch granule associated proteins (Han et al, 2001). Higher

resistance of teff starch to Rst compared to maize starch is an indication of inherent lower

granule deformability and swelling, since these were positively correlated to Rst resistance in

other native starches (Whistler and BeMiller, 1997).

The cold paste viscosity (CPV) of all the teff starches (mean 292 RVU) was considerably

lower than that of the maize starch paste (344 RVU). However, amylose-lipid complexing

reduces re-association to some extent (Whistler and BeMiller, 1997). Teff starches showed a

slight trend in their CPV, vrs. higher amylose contents giving higher CPV.

Figure 3.5, RVA pasting curves of starches from teff and maize. (Adapted by the writers,

from Bultosa et al, 2002)

The setback viscosity (SBV) of all the teff starches (mean 101 RVU) was considerably lower

than that of maize starch (161 RVU). The higher the SBV, the more syneresis is likely to take

place (Whistler and BeMiller, 1997). A preliminary observation on gel syneresis indicated that

teff starch showed slower syneresis than maize starch.

The water absorption index (WAI) of all the teff starches (mean 108%) was considerably

higher than that of maize starch (86%) (Table 3.6). The higher WAI of teff starch is probably

also related to its smaller granule size. The smaller the granular size of starch, the larger the

bulk surface area and the higher the water absorption. The high WAI of teff starch possibly

also contributes to the high volume of enjera made from teff flour, since from the same

weight of teff, maize, sorghum, wheat and barley flours, more enjera is obtained from teff

flour than from the other flours (personal communication of Bultosa et al from teff

improvement program of the Debre Zeit Agricultural Research Centre, Ethiopia)

0 5 10 15 20 25

0

80

60

160

240

320

30

90

120

Maize

Teff var mean

Time (min)

Viscosity (RVU)

Temperature (ºC)

[341]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

21

Table 3.6, Gelatinisation temperature, Water Absorption Index (WAI) and Water Solubility

Index (WSI) of starches from teff and maize.

Teff (five varieties mean)

Maize

Granule size (µm)

2-6

5-30

Gelatinisation temp. (ºC) (To-Tp-Tc)

68,0-74,0-80,0

65,0-73,0-80,0

WAI (%) (db)

108 ± 4

86 ± 2

WSI (%) (db)

0,34 ± 0,08

0,98 ± 0,06

To be onset, Tp is peak and Tc is conclusion gelatinisation temperatures; amylose [%]by the

Con A method of Gibson et al. and amylose [%]by the iodine binding of Chrastil.

Abstract made by the writers of this work, from Bultosa et al, 2002

Mean onset (To), peak (Tp) and conclusion (Tc) gelatinization temperatures of teff starches

were 68,0, 74,0 and 80,0 °C, respectively (Table 3.6). For the maize starch the values were

65,0, 73,0 and 80,0 °C, respectively. The teff starch gelatinisation temperature is thus similar

to that of tropical cereal starches and resembling most closely that of rice starch (68,0, 74,5,

78,0 °C). The range is somewhat narrower when compared to that for maize starch. Starch

gelatinisation is an irreversible process and includes granule swelling, native crystallite

melting, loss of birefringence and starch solubilisation.

The WSI of all teff starches (mean 0,34%) was considerably lower than that of maize starch

(mean 0,96%) (table 3.6).

Aerodynamic properties

Teff threshing is carried out in Ethiopia by trampling over the cut crop collected on a flat

surface with oxen. Separation of teff grain is carried out by throwing the grain and material

out of grain mix in air using the difference in aerodynamic properties. Cleaning is performed

by manually wafting air over the grain chaff mix with a dried hard leather strap (Zedwu,

2007).

Figure 3.6. Small and medium level grain cleaning. From

www.cd3wd.com/.../X0027S/ES/X0027S04.HTM

Bultosa and Taylor commented on the possibility of using a combine harvester for harvesting

of teff, but they added that teff grain losses can be high due to the very small size and light

mass of the grain. The equivalent diameter of teff grain was reported to vary between 0,71

and 0,87 mm and thousand grain mass 0,257–0,421 g (Zewdu & Solomon, 2007).

By defining the terminal velocity of different threshed materials, it is possible to determine

and set the maximum possible air velocity in which material out of grain (MOG) can be

[342]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

22

removed without loss of grain (Zewdu, 2004; Freye, 1980) or the principle can be applied to

classify grain into different size groups (Wu et al, 1999).

It is necessary then, to determine the aerodynamic properties of teff and straw in order to

apply this information in the design and construction of equipment to harvest, clean, transport

and store this grain. The two important aerodynamic characteristics of a body are its terminal

velocity and aerodynamic drag.

During the separation of threshed materials the fundamental forces involved are the weight

of the particle and the aerodynamic drag. Aerodynamic drag force is a function of the relative

velocity of the particle with air (vr), the density of air (ra), and the size of the particle as

expressed by its frontal area (Af). The drag force is related to properties of the particles and

of the fluid through the following relationship (Mohsenin, 1986):

Grain crop materials are usually small and irregular in shape, which makes direct drag force

measurements difficult. In order to predict drag coefficients the usual approach is to define

the shape of the material rough sphericity (Gorial & O’Callaghan, 1990). This is the ratio of

the surface area of a sphere equal in volume to that of the true surface area of the grain.

Once sphericity is established the drag coefficient can be established using relationships

proposed by different researchers.

Zedwu found that the terminal velocity of teff grain increased linearly from 3,08 to 3,96m/s as

shown in Fig. with increase in moisture content from 6,5% to 30,1% w.b. The resulting drag

coefficient of teff grain decreased from 0,83 to 0,65 with an increase in moisture content from

6,5% to 30,1% (Fig.). Both terminal velocity and drag coefficient were linearly related to

moisture content as shown in:

vt = 0,0363µ + 2,8858. (7)

CD =0,0074µ + 0,8627 (8)

with R2 values of 0,98 and 0,96, respectively. The decrease in drag coefficient is related to

the increase in mass and as well increased frontal area. The range of drag coefficients

showed that the teff grains behaved more like spheres when they had higher moisture

content. A linear increase in terminal velocity against moisture content is reported with most

terminal velocity measurements of seeds.

As a reason for the increase in terminal velocity, with moisture content, different authors cited

the increase in mass per unit frontal area.

Terminal velocity and drag coefficient of teff straw

Short straws are the major contaminant of threshed materials. They are also very difficult to

separate from the grain (Freye, 1980). Analising Zedwu results, it is possible to observe an

overlap in terminal velocities between grain and straw materials of teff. As a result, complete

pneumatic separation is not possible. In most cases the terminal velocities of end node

straws were greater than that of teff grain. This is likely due to the small size and weight of

teff grain.

[343]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

23

Figure 3.7, Effect of moisture content on terminal velocity of teff grain

Figure 3.8, Effect of moisture content on drag coefficient of teff grain

Processing modification of physical properties.

In all the food and beverage products in which teff are used, the starch granules are

structurally transformed (Bultosa and Taylor, 2004).

During the baking of enjera, starch is completely gelatinised to form a steam-leavened,

spongy textured matrix, in which fragments of bran, embryo, micro-organisms and organelles

are embedded. Gelatinised starches have a tendency to retrograde, which can affect the

texture and shelf-life acceptability of foods (Whistler and BeMiller, 1997). The smaller

setback and low cold paste viscosity of teff starch compared to maize starch is an indicator of

slow retro gradation tendency which might have a positive role in respect of storage stability

of food products made with teff starch.

0,85

0,80

0,75

0,65

0,70

0,60

Drag coefficient

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

Moisture content

(%)

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

Moisture content

(%)

3,1

2,8

4,0

3,7

3,4

2,5

Terminal velocity, m/s

[344]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

24

The differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) gelatinisation temperature is similar to that of

other tropical cereals. The lower swelling power, apparently lower percentage crystallinity

and lower DSC gelatinisation endotherms compared to maize starch suggest the degree of

crystallinity in the teff starch is less and the proportion of long amylopectin, a chain is

probably smaller (Bultosa, 2003).

Gelatinisation temperature range was 68,0–74,0–80,0 °C, typical of tropical cereal starches,

and resembling the temperature range of rice starch.

Figure 3.9, Differential scanning calorimeter.

From:http://content.answers.com/main/content/wp/en-commons/thumb/c/c8/288px-

Differential_scanning_calorimeter.jpg

The mean intrinsic peak viscosity (269 RVU), breakdown viscosity (79 RVU), cold paste

viscosity (292 RVU) and setback viscosity (101 RVU) determined were considerably lower

than that of maize starch. Teff starch has higher water absorption index (WAI) (mean 108%)

and lower water solubility index (WSI) (mean 0,34%) than maize starch.

Matrix change of starch was reported to be a major contributor to the texture of enjera

(Parker et al, 1989). During the baking of enjera, starch is completely gelatinised to form a

steam-leavened, spongy matrix, in which fragments of bran, embryo, micro-organisms and

organelles are embedded.

Bultosa et al, they think that the observed narrow gelatinisation temperature range for teff

starch is probably related in part to its relatively more uniform granule size distribution (2–6

μm in diameter) as compared with maize (5–30 μm in diameter) (Whistler and BeMiller,

1997), because in granules of wide size range like wheat (2–55 μm in diameter, 52 – 85 °C)

and barely (0,9–44,9 μm in diameter, 52,0 – 69,7 °C) (Tang et al, 2001) the range is broader.

Effect of chemical environment on teff physical properties.

An effective utilization of a new plant protein in food product formulation demands that its

food properties be investigated in order to find out whether such supplement possesses the

appropriate functional properties for acceptable food application (Akintayo et al, 1999;

Chavan et al, 2001). In addition to acceptable functionality, the development in food

[345]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

25

industries in the use of certain acids, alkali and salts in food formulation should be given a

due consideration since among their factors, physiochemical environment (pH, ionic strength,

presence or absence of surfactants), affect structural composition, interfacial tension and

energy of binding of food constituents, and in turn their functional performances (Chavan et

al, 2001; Philips et al, 1991; Yadav, 2002). These acids, alkalis and salts are added to foods

for a number of reasons: to improve nutritive values; control of acidity and alkalinity;

production of entrapped gas to initiate dough expansion; as leaving, preservative and

flavouring agents (Gimono, Astiasaran & Bello, 1999; Arongudade, 2005). Even though,

Arongudade made a study on this teff functional properties, and he determines these

functional properties and the effect of CH

3

COOH, NaHCO

3

, CaCO

3

and NaCl commonly

employed in food processing on such properties.

Least Gelation Concentration (LGC) of Eragrostis teff protein concentrate (ETPC) in distilled

water (control) was 6%, which is the same as that of bovine plasma protein concentrate, but

lower than soy flour and soy protein. The change in chemical environment had different

effect on ETPC gelation. Increase in the concentration of NaCl from 0,05 to 1,5 M gradually

improved the LGC from 6 to 2%. Saturated solution of NaHCO

3

also improved the LGC to

4%. But 0,05–1,5 MCH

3

- COOH and saturated solutions of CaCO

3

had no effect on the LGC

(Arongudade, 2005). The value LGC is taken as an index of gelation capacity

(http://images.google.nl/imgres?imgurl=http://content.answers.com/main/content/wp/en-

commons/thumb/c/c8/288px)

If the chemical environment is changed, the foaming capacity (FC) of ETPC is affected.

About two and half fold increase was observed in FC as the concentration of NaCl increased

from 0,0 to 0,5 M and later decreased at higher concentration (1,5 M) to 9,7% (this was

however still better than what was obtainable in distilled water—6,5%) (Arongudade, 2005).

A foam depression of 5,0 to 4,2% was observed in CH

3

COOH as concentration increased

from 0,05 to 1,0 M, respectively. This was later increased to 6,3% in 1,5 M CH

3

COOH.

Saturated solutions of NaHCO

3

and CaCO

3

gave an FC of 15,5 and 9,0%, respectively. The

results are displayed in fig.

Since chemical environment that are able to aid protein solubility and diffusion to the

interface do improve FC (Oshodi & Ojokan, 1997), Arongudade concluded that the ability of

CH

3

COOH, NaHCO

3

, NaCl and CaCO

3

to initiate protein solubility and diffusion in foam

formation are in the order of NaCl≈NaHCO

3

>CaCO

3

>CH

3

COOH.

NaCl

CH3COOH

Whipping volume (ml)

108

Control 0,05 0,10 0,50 1,00 1,50

Solution molar concentration (M)

96

102

106

100

116

114

112

Figure 3.10, Foaming capacity of ETPC in different concentration of NaCl and CH

3

COOH.

From Arongudade.

[346]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

26

3.3 Microbiology

The principal use of teff, is in enjera production, a flat bread, big and thin, that constitutes the

70% of Ethiopians diet. The preparation includes a fermentation step, that gives enjera their

sensorial characteristics, as flavour, aroma and colour. But the more important effect of teff

fermentation is an increase in the nutritional content, because the decreasing of the

relationships Iron:Phytates and Iron:Tannins.

Ersho is a clear, yellow liquid that accumulates on the surface of fermenting teff-flour batter

and is collected to serve as an inoculum for the next fermentation. The pH of ersho samples

was about 3,5 and titratable acidity ranged between 3,1% and 5,7%. Mean yeast counts

ranged between 5,2x105 and 1,8x10

6

cfu/ml and comprised, in order of abundance, Candida

milleri, Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, Kluyveromyces marxianus, Pichia naganishii and

Debaromyces hansenii. Candida milleri was the most dominant isolate in all samples. Other

authors, they found as the principal responsible of teff fermentation Candida guillermondi.

About 90% of the teff flour samples had aerobic mesophilic counts ≥ 105 cfu/g and Gram-

positive bacteria constituted about 71% of the total isolates. About 80% of samples had

Enterobacteriaceae counts of 10

4

cfu/g. Before of the Ashenafi work, Gifawossen and Bisrat

(1982) were able to isolated Candida and Pichia from ersho.

The preparation of teff enjera consists of two stages of natural fermentation, which last for

about 24 to 72 h, depending on ambient temperatures. The only required ingredients are the

teff flour and water. Inoculation is accomplished by consistently using a partially-cleaned

fermentation container and by adding some ersho. This ersho contains 96,4% moisture, 0,05

mg riboflavin/100 g, and 0,4 rag niacin/ 100 g (Steinkraus 1983). About 480 g ersho is added

to 3 kg teff flour and 6 1 water. The various traditional teff threshing processes mean that teff

flour probably contains a very wide variety of soil and faecal micro organisms.

Ashenafi concluded that the very low pH values of the ersho (about 3,5), consistently

recorded for all samples, and would be inhibitory for most kinds of micro organisms. The

absence of members of Enterobacteriaceae or lactic acid bacteria, which were reported to be

important in teff fermentation (Gashe et al. 1982), indicated that the ersho could not serve as

a source of these bacteria (Ashenafi, 1994).

Figure 3.11, Injera, with a vegetables sauce. From

www.globalnomad.net/.../print_quick%20facts.htm

[347]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

27

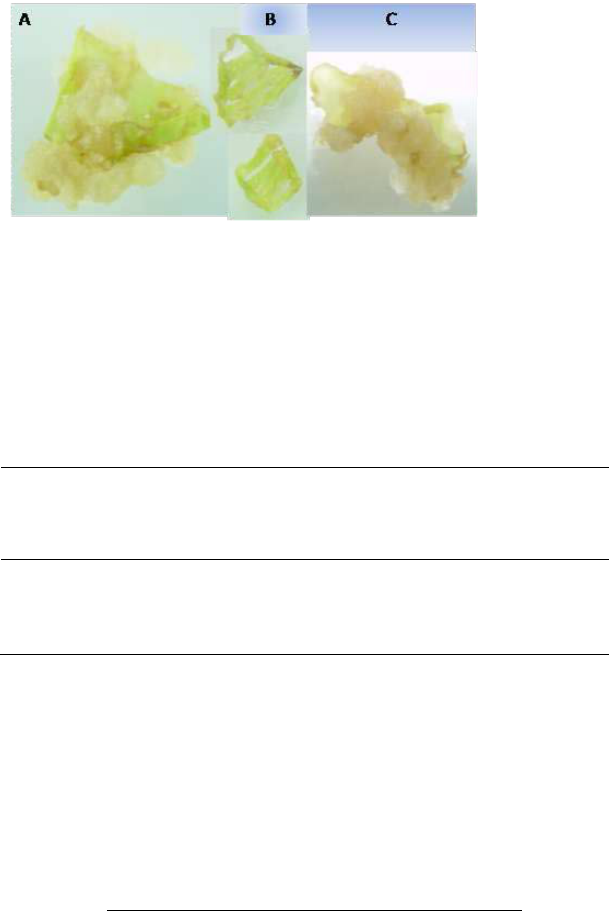

Figure 3.12, Some of the microorganisms found in ersho, and that participate in the teff

fermentation process. Candida and Pichia.

From: http://www.jgi.doe.gov/education/bioenergy/Pichia_stipitis_JGI.jpg

Althout Candida milleri is the most abundant yeast found by Asehenafi, in the different

households analysed, he could found different Candida species. This variation may be one of

the reasons why enjera produced at one household at different times or in different

households could have different flavours (Ashenafi, 1994).

Figure 3.13, Microbiological ersho composition, adapted by the authors from Ashenafi, 1994.

The physiological properties of the yeast isolates in this study indicated that the Candida and

Kluyveromyces species were active gas producers from glucose, sucrose and a variety of

100

Fig. Distribution of C. milleri ( ), R. mucilaginosa ( ), K. marxianus ( ),

P. naganishi ( ) and D. hansenti ( ) in ersho samples, collected from four

households.

80

40

20

0

60

Positive samples ( % of total)

[348]

memorias * red-alfa lagrotech * comunidad europea * cartagena 2008

The literature research to the cereal teff (Eragrostis Tef) _________

Patricia Arguedas & Lisette van Ekris

28

other sugars. Pichia naganishii and Debaromyces hansenii produced a certain amount of gas

from glucose only. The starch is not utilized for fermentation. That means that these micro

organisms are not able to hydrolyse the starch molecule. These species could only be

important in the fermentation of teff then fermentable sugars are available after the

degradation of teff starch (Ashenafi, 1994).

The second most frequently isolated species, R. mucilaginosa, was fermentative inactive and

may not therefore be important in leavening the batter of teff.

Since ersho is the clear yellow liquid decanted from the batter at the end of the primary

fermentation the yeast flora isolated from ersho, even those which were fermentative very

active, may not be important as starters in the initiation of teff fermentation.

Another source of inoculums for teff fermentation could be the teff flour itself. The traditional

threshing processes of teff result in the contamination of the teff seeds with a very wide

variety of soil and faecal material (Gashe et al, 1982; Steinkraus 1983). Gram-positive

bacteria dominated the aerobic flora of teff in Asehnafi study and among these, micrococci