LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND

TRANSGENDER YOUTH

An Epidemic of

Homelessness

by Nicholas Ray

with chapters contributed by

Colby Berger, Waltham House, Waltham, Mass.

Susan Boyle, Urban Peak, Denver, Colo.

Mary Jo Callan and Mia White, Ozone House, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Grace McCelland, Ruth Ellis Center, Detroit, Mich.

Theresa Nolan, Green Chimneys, New York, N.Y.

National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute

National Coalition for the Homeless

ii

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

The National Gay and Lesbian Task

Force Policy Institute is a think tank

dedicated to research, policy analysis and

strategy development to advance greater

understanding and equality for lesbian,

gay, bisexual, and transgender people.

Washington, DC

1325 Massachusetts Ave NW, Suite 600

Washington, DC 20005-4171

Tel 202

393

5177

Fax 202

393

2241

New York, NY

80 Maiden Lane, Suite 1504

New York, NY 10038

Tel 212

604

9830

Fax 212

604

9831

Los Angeles, CA

8704 Santa Monica Blvd, Suite 200

West Hollywood, CA 90069

Tel 310 855 7380

Fax 310 358 9415

ngltf@thetaskforce.org

Cambridge, MA

1151 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

Tel 617

492

6393

Fax 617

492

0175

Miami, FL

3510 Biscayne Blvd Suite 206

Miami, FL 33137

Tel 305 571 1924

Fax 305 571 7298

Minneapolis, MN

810 West 31st Street

Mineeapolis, MN 55408

Tel/Fax 612 821 4397

www.thetaskforce.org

© 2006 The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute

When referencing this document, we recommend the following citation:

Ray, N. (2006). Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth: An epidemic

of homelessness. New York: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy

Institute and the National Coalition for the Homeless.

National Coalition

for the Homeless

www.nationalhomeless.org

iii

iii

Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

Why are so many LGBT youth becoming homeless? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

What impact does homelessness have on LGBT youth specifically?

. . . . . . . . . . . . .2

Mental health issues

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

Substance abuse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

Risky sexual behavior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3

Victimization of homeless LGBT youth

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

LGBT homeless youth and the Juvenile and criminal justice systems . . . . . . . . .

3

Transgender homeless youth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4

The federal response to youth homelessness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4

The potential for anti-LGBT discrimination at faith-based service providers

. . .4

The experiences of LGBT homeless youth in the shelter system . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

Model programs to improve service delivery to LGBT homeless youth

. . . . . . . . . . .6

Conclusion and policy recommendations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

Federal level recommendations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

State and local level recommendations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Practitioner level recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

What is the definition of “homeless youth?”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

HOW MANY LGBT HOMELESS YOUTH ARE THERE

AND WHY DO THEY BECOME HOMELESS? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

A note on acronyms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11

Barriers to a more accurate count . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

Why do youth become homeless?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

Sexual orientation and gender identity issues

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

Physical or sexual assault . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

Additional factors that lead to homelessness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

Why do youth remain homeless?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

THE FEDERAL RESPONSE TO YOUTH HOMELESSNESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24

The Runaway and Homeless Youth Act . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

A brief legislative history

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

Congress acts

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27

iv

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

Federal programs for homeless youth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28

Basic Center Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

Street Outreach Program

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .29

Transitional Living Program

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30

National Runaway Switchboard . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

31

Federal funding under the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act

. . . . . . . . . . . .31

Table 1: Federal RHYA Funding 2001 to 2006 ($ in millions)

. . . . . . . . . . . . .32

McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

32

The impact of federal immigration policy on LGBT homeless youth

. . . . . . . . . . . .35

Organizational advocacy for people experiencing homelessness

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .36

Faith-based service providers

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37

The Potential for anti-LGBT discrimination at faith-based service providers

. .39

CRITICAL ISSUES AFFECTING LGBT HOMELESS YOUTH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .41

Mental health issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

41

How are homeless youth affected?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .42

Mental health crises facing LGBT youth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

43

Mental health services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .45

Substance abuse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

46

Table 2: Percentage of youth in different housing

situations and the substances they use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .47

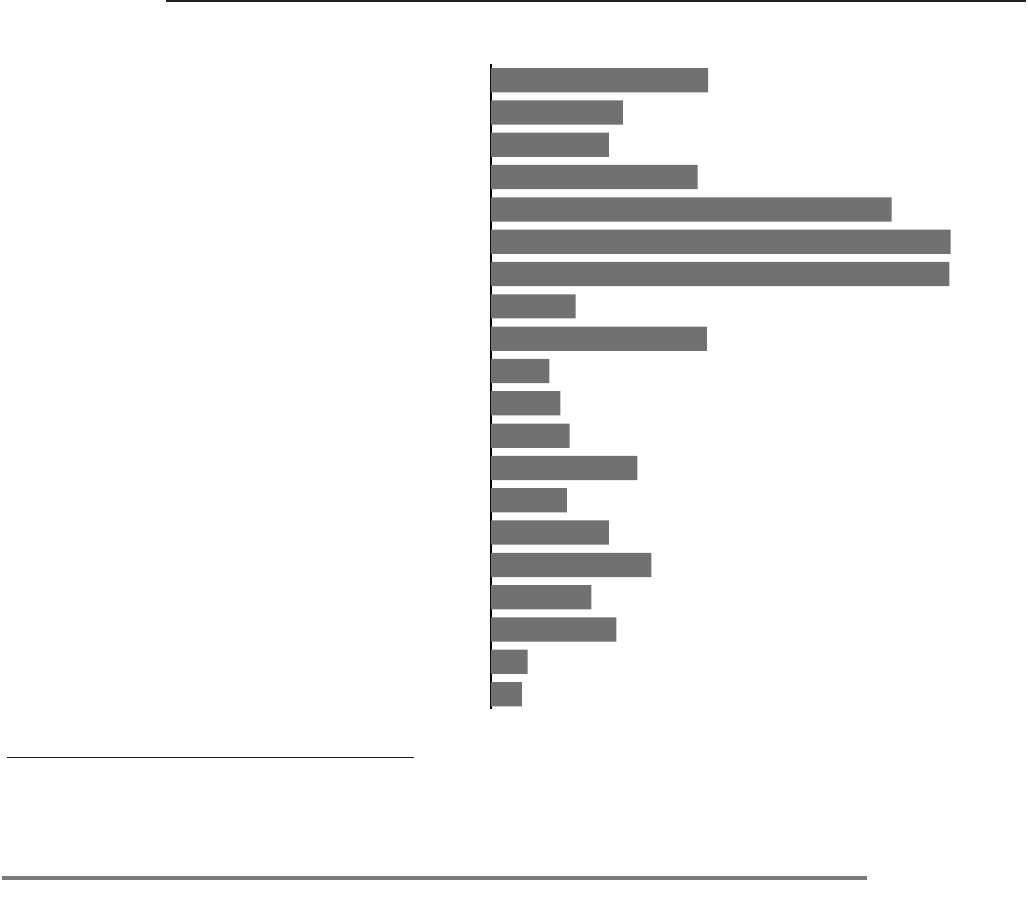

Figure 1: Lifetime substance use by homeless youth

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .48

Substance use and LGBT youth

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .49

Risky Sexual Behavior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

53

Risky behavior in homeless LGBT youth

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .53

Sexual health risks for homeless youth populations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

53

Determinants of sexual health of homeless youth

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .54

Survival sex

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .55

The experience of transgender homeless youth

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

Access to medical care for the homeless transgender community

. . . . . . . . . .60

Figure 2: A summary of risky behaviors reported by trans-identified youth . . .

62

Risks facing homeless transgender y

outh . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .62

Community-based health centers reaching out to

low and no income transgender people . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .64

Crime and victimization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

66

Physical and verbal harassment in school . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

66

Young and homeless victims of crime

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .67

The criminalization of homelessness

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .71

The juvenile and criminal justice systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

73

LGBT people in prison

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .73

Rape in prisons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

74

LGBT youth in the juvenile justice system . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

77

Resiliency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

EXPERIENCES OF HOMELESS LGBT YOUTH IN THE SHELTER SYSTEM . . . . . . . . . . . .83

Faith-based programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

85

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

vv

RUTH ELLIS CENTER:STREET OUTREACH PROGRAM AND DROP-IN CENTER . . . . . .91

History and background

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .91

Characteristics of our youth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

92

Collaborations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

Staffing our programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

93

The Street Outreach Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

95

The Drop-in Center . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

96

Positive Youth Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

Sexual abuse and exploitation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

98

Range of services

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .99

Program impact

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .100

Barriers to success . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

101

Evaluation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .102

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

GREEN CHIMNEYS: TRIANGLE TRIBE

APARTMENTS TRANSITIONAL LIVING PROGRAM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .104

New York City programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

105

Employee/volunteer data

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .105

Collaborations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

What is transitional living?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .106

History and development of the Triangle Tribe Apartments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

108

The mission and philosophy of Green Chimneys transitional programming . . . . . .

110

Practice: How it operates

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .110

Why it works: Statistics and other signs of success

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .113

Challenges and overcoming them . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

114

Evaluation: Agency and program

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .114

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

OZONE HOUSE: MAKING EVERY SPACE A SAFE SPACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .116

Safety, support and affirmation:

Developing an agency culture for effective work with LGBT youth . . . . . . . . . . . .118

Approach to services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

120

Developing youth & capitalizing on their strengths

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .121

Empowerment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121

Responsiveness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121

Holistic approach

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .121

Strategies for achieving our mission

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .122

Committing to an alternative culture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

122

Ensuring physical manifestations of safety . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

122

Professional development

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .122

Formalized training

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .122

Effective supervision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

123

Social learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

123

Taking the lead from youth

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .123

Maximizing teachable moments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

124

Recruiting LGBT staff and volunteers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

124

Advocacy and systems change

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .125

Reducing and eliminating barriers to service . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

126

Contents

vi

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

Case-level advocacy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126

Policy-level advocacy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

126

Agency policies & procedures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

126

An inclusive definition of “family”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .126

A Hostile Language Policy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .126

Policy and practice bodies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

127

Outcomes and expected results

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .128

Outcome 1: Safety for runaway, homeless and high-risk youth . . . . . . . . . . .

128

Outcome 2: Emotional safety for LGBT and questioning youth . . . . . . . . . . .

129

Outcome 3: Cultural competence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

129

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

URBAN PEAK: WORKING WITH HOMELESS

TRANSGENDER YOUTH IN A SHELTER ENVIRONMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .131

Introduction & overview:

The challenge of making spaces safe for transgender youth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132

Working with transgender youth: Building trust and maintaining a safe space . . 13

2

Sex and gender identity: terms and d

efinitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

Guidelines for providing shelter services to transgender p

eople . . . . . . . . . . . 134

Basic guidelines for creating a transgender youth-friendly shelter . . . . . . . . . . . . .

135

Developing a supportive staff . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

135

Developing supportive policies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

135

Policy of r

espect . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .136

Intake process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

136

Housing and sex-segregated f

acilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

Harassment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .137

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .138

WALTHAM HOUSE: TRAINING MODELS TO

IMPROVE INTERACTIONS WITH LGBT OUT-OF-HOME YOUTH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .139

Working with the State of Massachusetts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

141

History and overview of the initiative

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .142

Implementation of the training program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

145

The training curriculum

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .147

Training session outcomes and highlights

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .149

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .153

Federal-level recommendations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .154

State- and local-level recommendations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .156

Practitioner-level recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

160

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161

REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .162

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .179

TASK FORCE FUNDERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .182

1

Executive

summary

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that the number of home-

less and runaway youth ranges from 575,000 to 1.6 million per year.

1

Our analysis of the

available research suggests that between 20 percent and 40 percent of all homeless youth

identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT).

2

LGBT

youth experience homelessness at a disproportionate rate, prompting

the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (the Task Force), in

collaboration with the National Coalition for the Homeless (NCH),

to produce this publication.

Through a comprehensive review of the available academic research

and professional literature, we answer some basic questions, including

why so many LGBT youth are becoming and remaining homeless.

We report on the harassment and violence that many of these youth

experience in the shelter system and we summarize research on

critical problems affecting them, including mental health issues,

substance abuse and risky sexual behavior. We also analyze the

federal government’s response to youth homelessness, including the specific impact on

LGBT homeless youth of increased federal funding for faith-based service providers.

We also partnered with five social service agencies who have written sections that detail

model programs they have developed to improve service delivery to LGBT homeless

youth. In order to put a face to all of this research and data, we also include profiles of

LGBT homeless youth, many of which were collected through focus groups we conducted

at service providers around the country. Finally, in consultation with a number of youth

advocacy organizations, we conclude with a series of state-, federal- and practitioner-level

policy recommendations that can help to curb this epidemic.

WHY ARE SO MANY LGBT YOUTH BECOMING HOMELESS?

Family conflict is the primary cause of homelessness for all youth, LGBT or straight.

Specifically, familial conflict over a youth’s sexual orientation or gender identity is

1 Robertson, M. J. & Toro, P. A. (1998). Homeless youth: Research, intervention, and policy. United States Department of Health and

Human Services. Retrieved June 3, 2005, from http://aspe.hhs.gov/progsys/homeless/symposium/3-Youth.htm

2 See pages 11 to 14 of the full report for a more detailed summary of the available research.

Our analysis of the

available research

suggests that between

20 percent and 40

percent of all homeless

youth identify as

lesbian, gay, bisexual or

transgender (LGBT).

2

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

a significant factor that leads to homelessness or the need for

out-of-home care.

3

According to one study, 50 percent of gay teens

experienced a negative reaction from their parents when they came

out and 26 percent were kicked out of their homes.

4

Another study

found that more than one-third of youth who are homeless or in the

care of social services experienced a violent physical assault when

they came out,

5

which can lead to youth leaving a shelter or foster

home because they actually feel safer on the streets.

WHAT IMPACT DOES HOMELESSNESS HAVE

ON LGBT YOUTH SPECIFICALLY?

Whether LGBT youth are homeless on the streets or in temporary shelter, our review of

the available research reveals that they face a multitude of ongoing crises that threaten

their chances of becoming healthy, independent adults.

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES

LGBT homeless youth are especially vulnerable to depression, loneliness and psychoso-

matic illness,

6

withdrawn behavior, social problems and delinquency.

7

According to the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the fact that LGBT youth live in “a

society that discriminates against and stigmatizes homosexuals” makes them more vulner

-

able to mental health issues than heterosexual youth.

8

This vulnerability is only magnified

for LGBT youth who are homeless.

SUBSTANCE ABUSE

The combination of stressors inherent to the daily life of homeless youth leads them to

abuse drugs and alcohol. For example, in Minnesota, five separate statewide studies found

that between 10 and 20 percent of homeless youth self-identify as chemically dependent.

9

These risks are exacerbated for homeless youth identifying as lesbian, gay or bisexual

(LGB).

10

Personal drug usage, family drug usage, and the likelihood of enrolling in a treat-

ment program are all higher for LGB homeless youth than for their heterosexual peers.

11

3 Clatts, M. J., Davis, W. J., Sotheran, J. L. & Atillasoy, A. (1998). Correlates and distribution of HIV risk behaviors among homeless

youth in New York City. Child Welfare, 77(2). See also Hyde, J. (2005). From home to street: Understanding young people’s transitions

into homelessness. Journal of Adolescence, 28. p.175.

4 Remafedi, G. (1987). Male homosexuality: The adolescent perspective. Pediatrics, (79).

5 Thompson, S. J., Safyer, A. W. & Pollio, D. E. (2001). Differences and predictors of family reunification among subgroups of runaway

youths using shelter services. Social Work Research, 25(3).

6 McWhirter, B. T. (1990). Loneliness: A review of current literature with implications for counseling and research. Journal of Counseling

and Development, 68.

7 Cochran, B. N., Stewart, A. J., Ginzler, J. A. & Cauce, A. M. (2002). Challenges faced by homeless sexual minorities: Comparison of

gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender homeless adolescents with their heterosexual counterparts. American Journal of Public Health,

92(5). pp.774-775.

8 Gibson, P. (1989). Gay male and lesbian youth suicide, vol. 3: Preventions and interventions in youth suicide. In Report of the secretary’s

task force on youth suicide. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

9 Wilder Research. (2005). Homeless youth in Minnesota: 2003 statewide survey of people without permanent shelter. Author. Retrieved June

26, 2006, from http://www.wilder.org/download.0.html?report=410. p.27.

10 Van Leeuwen, J. M., Boyle, S., Salmonsen-Sautel, S., Baker, D. N., Garcia, J., Hoffman, A., & Hopfer, C. J. (2006). Lesbian, gay and

bisexual homeless youth: An eight city public health perspective. Unpublished work.

11 Ibid., p.18.

According to one study,

26 percent of gay teens

were kicked out of their

homes when they came

out to their parents.

3

RISKY SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

All homeless youth are especially vulnerable to engaging in risky

sexual behaviors because their basic needs for food and shelter are

not being met.

12

Defined as “exchanging sex for anything needed,

including money, food, clothes, a place to stay or drugs,”

13

survival

sex is the last resort for many LGBT homeless youth. A study of

homeless youth in Canada found that those who identify as LGBT

were three times more likely to participate in survival sex than their

heterosexual peers,

14

and 50 percent of homeless youth in another

study considered it likely or very likely that they will someday test

positive for HIV.

15

VICTIMIZATION OF HOMELESS LGBT YOUTH

LGBT youth face the threat of victimization everywhere: at home, at school, at their

jobs, and, for those who are out-of-home, at shelters and on the streets. According to the

National Runaway Switchboard, LGBT homeless youth are seven times more likely than

their heterosexual peers to be victims of a crime.

16

While some public safety agencies try

to help this vulnerable population,

17

others adopt a “blame the victim” approach, further

decreasing the odds of victimized youth feeling safe reporting their experiences.

18

LGBT HOMELESS YOUTH AND THE JUVENILE

AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMS

While there is a paucity of academic research about the experiences of LGBT youth who

end up in the juvenile and criminal justice systems, preliminary evidence suggests that

they are disproportionately the victims of harassment and violence, including rape. For

example, respondents in one small study reported that lesbians and bisexual girls are

overrepresented in the juvenile justice system and that they are forced to live among a

population of inmates who are violently homophobic.

19

Gay male youth in the system are

also emotionally, physically and sexually assaulted by staff and inmates. One respondent

in a study of the legal rights of young people in state custody reported that staff members

think that “[if] a youth is gay, they want to have sex with all the other boys, so they did

not protect me from unwanted sexual advances.”

20

A study of homeless

youth in Canada found

that those who identify

as LGBT were three times

more likely to participate

in survival sex than their

heterosexual peers.

12 Rosenthal, D. & Moore, S. (1994). Homeless youths: Sexual and drug-related behavior, sexual beliefs and HIV/AIDS risk. AIDS Care,

6(1).

13 Cited in Anderson, J. E., Freese, T. E. & Pennbridge, J. N. (1994). Sexual risk and condom use among street youth in Hollywood. Family

Planning Perspectives, 26(1). p.23.

14 Gaetz, S. (2004). Safe streets for whom? Homeless youth, social exclusion, and criminal victimization. Canadian Journal of Criminology

and Criminal Justice, 46(6).

15 Kihara, D. (1999). Giuliani’s suppressed report on homeless youth. The Village Voice, 44(33).

16 National Runaway Switchboard. (2005).

17 Dylan, N. (2004). City enters partnership to assist lesbian and gay homeless youth. Nation’s Cities Weekly, 27(10).

18 Bounds, A. (2002, September 24). Intolerance discussed BHS school offers weeklong focus on tolerance. Boulder Daily Camera. p.C3.

See also: D’Augelli, A. R. & Hershberger, S. L. (1993). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings: Personal challenges and

mental health problems. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21(4). See also: Arnott, J. (1994). Gays and lesbians in the criminal

justice system. In Multicultural Perspectives in Criminal Justice and Criminology. Springfield, OH: C. Thomas Charles.

19 Curtin, M. (2002). Lesbian and bisexual girls in the juvenile justice system. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 19(4).

20 Estrada, R. & Marksamer, J. (2006). The legal rights of young people in state custody: What child welfare and juvenile justice profes-

sionals need to know when working with LGBT youth. Child Welfare, 85(2).

Executive Summary

4

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

TRANSGENDER HOMELESS YOUTH

Transgender youth are disproportionately represented in the homeless population. More

generally, some reports indicate that one in five transgender individuals need or are at risk

of needing homeless shelter assistance.

21

However, most shelters are segregated by birth

sex, regardless of the individual’s gender identity,

22

and homeless transgender youth are

even ostracized by some agencies that serve their LGB peers.

23

THE FEDERAL RESPONSE TO YOUTH HOMELESSNESS

Since 1974, when the federal government enacted the original Runaway Youth Act, there

have been numerous pieces of legislation addressing youth homelessness. Most recently, the

Runaway, Homeless and Missing Children Protection Act (RHMCPA) was signed into law

by President George W. Bush in 2003 and is up for reauthorization in 2008.

24

Among the most important provisions of this complex piece of legislation are programs

that allocate funding for core homeless youth services, including basic drop-in centers,

street outreach efforts, transitional living programs (TLPs) and the National Runaway

Switchboard. While the law does not allocate funding for LGBT-specific services, some

funds have been awarded to agencies who work exclusively with LGBT youth, as well as

those who seek to serve LGBT homeless youth as part of a broader mission.

Unfortunately, homeless youth programs have been grossly under funded, contributing to

a shortfall of available spaces for youth who need support. In 2004 alone, due to this lack

of funding, more than 2,500 youth were denied access to a TLP program for which they

were otherwise qualified.

25

Additionally, 4,200 youth were turned away from Basic Center

Programs, which provide family reunification services and emergency shelter.

26

THE POTENTIAL FOR ANTI-LGBT DISCRIMINATION

AT FAITH-BASED SERVICE PROVIDERS

Lack of funding is not the only obstacle preventing LGBT homeless youth from

receiving the services they need. In 2002, President George W. Bush issued an executive

order permitting federal funding for faith-based organizations (FBOs) to provide social

services.

27

While more and more FBOs are receiving federal funds, overall funding levels

for homeless youth services have not increased. Consequently, there is a possibility that

the impact of FBOs will not be to increase services to the homeless, but rather only to

change

who provides those services.

A number of faith-based providers oppose legal and social equality for LGBT people, which

21 Cited in Mottet, L. & Ohle, J. M. (2003). Transitioning our shelters: A guide to making homeless shelters safe for transgender people. Retrieved

June 12, 2006, from http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/TransHomeless.pdf

22 Ibid.

23

HCH Clinicians’ Network (2002, June). Crossing to safety: Transgender health & homelessness. Healing Hands, 6, pp. 1-6.

24 Public Law 108-96 for fiscal years 2004 through 2008.

25 Data compiled from the federally administered Runaway and Homeless Youth Management Information System (RHYMIS).

26 Project HOPE: Virginia education for homeless children and youth program. (2006). Runaway and Homeless Youth Act programs:

Strengthening youth and families in every community. Author. Retrieved September 10, 2006, from http://www.wm.edu/hope/Seminar/

RHYA.pdf

27 White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives. (2006). President Bush’s faith-based and community initiative.

Author. Retrieved August 31, 2006, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/government/fbci/mission.html

5

raises serious questions about whether LGBT homeless youth can access services in a safe

and nurturing environment. If an organization’s core belief is that homosexuality is wrong,

that organization (and its committed leaders and volunteers) may not respect a client’s sexual

orientation or gender identity and may expose LGBT youth to discriminatory treatment.

For example, an internal Salvation Army document obtained by the

Washington Post in 2001 confirmed that “…the White House had

made a ‘firm commitment’ to issue a regulation protecting religious

charities from state and city efforts to prevent discrimination against

gays in hiring and providing benefits.”

28

Public policy that exempts

religious organizations providing social services from non-discrimi

-

nation laws in hiring sets a dangerous precedent. If an otherwise

qualified employee can be fired simply because of their sexual

orientation or gender identity/expression, what guarantee is there

that clients, including LGBT homeless youth, will be supported and

treated fairly? More research is needed on the policies of FBOs that

provide services for LGBT homeless youth.

THE EXPERIENCES OF LGBT HOMELESS

YOUTH IN THE SHELTER SYSTEM

The majority of existing shelters and other care systems are not providing safe and

effective services to LGBT homeless youth.

29

For example, in New York City, more than

60 percent of beds for homeless youth are provided by Covenant House, a facility where

LGBT youth report that they have been threatened, belittled and abused by staff and

other youth because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

30

At one residential placement facility in Michigan, LGBT teens, or those suspected of

being LGBT, were forced to wear orange jumpsuits to alert staff and other residents. At

another transitional housing placement, staff removed the bedroom door of an out gay

youth, supposedly to ward off any homosexual behavior. The second bed in the room was

left empty and other residents were warned that if they misbehaved they would have to

share the room with the “gay kid.”

31

LGBT homeless youth at the Home for Little Wanderers in Massachusetts have reported

being kicked out of other agencies when they revealed their sexual orientation or gender

identity. Many also said that the risks inherent to living in a space that was not protecting

them made them think that they were better off having unsafe sex and contracting HIV

because they would then be eligible for specific housing funds reserved for HIV-positive

homeless people in need.

32

If an organization’s

core belief is that

homosexuality is wrong,

that organization (and its

leaders and volunteers)

may not respect a client’s

sexual orientation or

gender identity and may

expose LGBT youth to

discriminatory treatment.

28 Allen, M. & Milbank, D. (2001, July 12). Rove heard charity plea on gay bias. Washington Post. Retrieved September 25, 2006, from

http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A48279-2001Jul11?language=printer.

29 Mallon, G. P. (1997). The delivery of child welfare services to gay and lesbian adolescents. In Central Toronto Youth Services, Pride and

Prejudice: Working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Toronto: Central Toronto Youth Services.

30 Email communication between the author and the Empire State Coalition of Youth and Family Services. New York, NY. See also:

Murphy, J. (2005). Wounded pride: LGBT kids say city-funded shelter for the homeless breaks its covenant. Village Voice. Retrieved September

10, 2006, from http://www.villagevoice.com/news/0517,murphy1,63374,5.html

31 Both examples were confirmed in personal conversations between the author and social service agency staff who had worked at the

offending agencies, or had worked with youth who had resided at those agencies.

32 As confirmed by Colby Berger, LGBT training manager at Waltham House.

Executive Summary

6

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

MODEL PROGRAMS TO IMPROVE SERVICE

DELIVERY TO LGBT HOMELESS YOUTH

Despite the potential for mistreatment of LGBT homeless youth by some agencies, there

are others who set an example for their peers. Our five contributing homeless youth

service providers represent the diverse range of agencies working with homeless LGBT

youth, though they are by no means the only agencies doing great work. We hope that

sharing their expertise will in turn help other agencies to improve the service and support

they provide to this community.

1. Theresa Nolan of Green Chimneys in New York City discusses the role of transitional

living programs in the continuum of care that LGBT youth experiencing homeless

-

ness might pass through.

2. Colby Berger of Waltham House in Massachusetts provides a case study of how her

agency worked in collaboration with the state department of social services to train

thousands of professional staff who work with homeless youth about LGBT issues.

3. Grace McClelland from the Ruth Ellis Center in Detroit, an organization that works

primarily with homeless LGBT youth of color, provides a description of the Center’s

street outreach and drop-in center programming.

4. Mary Jo Callan and Mia White from Ozone House in Ann Arbor, Michigan discuss

how their staff created a LGBT-safe space at an agency that works predominantly with

heterosexual youth.

5. Susan Boyle of Urban Peak in Denver, Colorado describes policies and procedures

that make shelters safe and welcoming for transgender homeless youth.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

This report concludes with a series of policy recommendations that

can help to curb the epidemic of LGBT youth homelessness. While

our focus in this publication and in these policy recommendations

is to address LGBT-specific concerns, we believe that homelessness is

not an issue that can be tackled piecemeal. Wholesale improvement

is needed, and that is what we propose. Our recommendations are

not intended to be an exhaustive list of every policy change that

would make the experience of homeless youth better. Rather, we

highlight some of the crucial problem areas where policy change is

both needed and reasonably possible.

FEDERAL LEVEL RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Reauthorize and increase appropriations for federal Runaway and Homeless Youth

Act (RHYA) programs.

2. Permit youth who are minors, especially unaccompanied minors, to receive primary

and specialty health care services without the consent of a parent or guardian.

3. Develop a national estimate of the incidence and prevalence of homelessness among

Homelessness is not

an issue that can be

tackled piecemeal.

Wholesale improvement

is needed, and that is

what we propose.

7

American youth, gathering data that aids in the provision of appropriate services.

4. Authorize and appropriate federal funds for developmental, preventive and interven

-

tion programs targeted to LGBT youth.

5. Raise federal and state minimum wages to an appropriate level.

6. Broaden the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition of

“homeless individual” to include living arrangements common to homeless youth.

STATE AND LOCAL LEVEL RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Establish funding streams to provide housing options for all homeless youth. Require

that recipients of these funds are committed to the safe and appropriate treatment

of LGBT homeless youth, with penalties for non-compliance including the loss of

government funding. These funds would supplement federal appropriations.

2. Permit dedicated shelter space and housing for LGBT youth.

3. Repeal existing laws and policies that prevent single and partnered LGBT individuals

from serving as adoptive and foster parents.

4. Discourage the criminalization of homelessness and the activities inherent to the

daily lives of people experiencing homelessness.

5. Expand the availability of comprehensive health insurance and services to all low-

income youth through the age of 24 via Medicaid.

PRACTITIONER LEVEL RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Require all agencies that seek government funding and licensure to serve homeless

youth to demonstrate awareness and cultural competency of LGBT issues and popula

-

tions at the institutional level and to adopt nondiscrimination policies for LGBT

youth.

2. Mandate individual-level LGBT awareness training and demonstrated cultural

competency as a part of the professional licensing process of all health and social

service professions.

3. Mandate LGBT awareness training for all state agency staff who work in child welfare

or juvenile justice divisions.

CONCLUSION

Once implemented, these policy recommendations will help not only LGBT homeless

youth, but all youth abandoned by their family or forced to leave home. In this report,

we extensively review the academic and professional literature on the myriad challenges

faced by LGBT homeless youth. The research shows that despite these challenges, many of

these youth are remarkably resilient and have benefited from support from agencies like

those in our model programs chapters who have worked to ensure that youth feel safe,

welcome and supported. Regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity, every young

person deserves a safe and nurturing environment in which to grow and learn. It is our

hope that this report will bring renewed attention to an issue that has been inadequately

addressed for far too long.

Executive Summary

8

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

Introduction

I believe that one day, the Lord will come back to get me. Halleluiah.

If I live right, halleluiah, I will go on to that righteous place.

I believe that one day, halleluiah, all my trials, all my tribulations, they will all be over.

I won’t have to worry about crying and suffering no more.

I won’t have to worry about being disappointed, because my God,

halleluiah, is coming back for me.

Whether I’m a man with a dress and a wig, My God will love me for who I am!

I might not walk like I’m supposed to walk.

I might not have sex with who I’m supposed to have sex with.

My God will love me for who I am!

So don’t worry about me, worry about yourself.

Because as long as my God believes in me,

I’m not worried about what folks say, halleluiah.

—Ali Forney

A homeless transgender youth in New York City,

speaking at the Safe Space talent show in 1996

Ali Forney, a homeless African-American transgender youth, recited this poem while

enjoying his

33

favorite event of the year: talent night at Safe Space, a program for homeless

youth in New York City. It was December 1996, and after years of homelessness, drug

abuse and prostitution, Ali was dedicating much of his

time to helping other homeless lesbian, gay, bisexual and

transgender (LGBT) youth. The poem declared his convic

-

tion that he had a right to live a life based on honesty and

integrity, despite the hurt he had experienced.

Less than one year after Ali spoke at the talent show,

Carl Siciliano, today executive director of the Ali Forney

Center for LGBT homeless youth in New York City,

spoke the same words in tribute at Ali’s funeral after he

was murdered by a still-unidentified assailant at 4 a.m. on

a cold winter night. We begin by summarizing Ali’s story

33 Carl Siciliano, executive director of the Ali Forney Center, confirms that Ali identified as both gay and transgender, sometime referring

to himself as “he” and at other times referring to herself as “she.” Sometimes he went by his given name, and at other times she went by the

name “Luscious.” In this profile, we have used male pronouns because that is the form adopted by the various media sources we cited.

9

because it reflects so many of the issues we cover in this publication.

At the time of his death, Ali was working with staff at Safe Horizon’s Streetwork program

as an outreach worker, helping other homeless youth.

34

He was determined to repay the

agency, which had helped him get a Social Security card, medical insurance and his GED,

by educating his peers. “I became a peer educator because I see so many HIV-infected

people on the stroll. Even now, there are people who don’t know how to use condoms.”

35

Despite his outreach work educating less-informed street workers, Ali continued to trick

and it was not his only high-risk behavior. He readily admitted to being a drug addict,

commenting that his crack cocaine use became a habit “because it eased the degradation

and fear of selling himself.”

36

Ali’s honest

assessment of his drug use is reflective of

the available academic literature, which attests

to the prevalence of drug use among LGBT

homeless youth and its impact on other risky

behaviors.

As was the case for Ali, so much of what leads

to homelessness among LGBT youth can be

traced to experiences at home. He grew up

with his single mother in a housing project in

a violent area of Brooklyn, “a world of poverty-

blighted high-rises, beat-up cars, stark store

fronts and warehouses.”

37

It was certainly not

an easy place for a transgender youth to live.

He spent years getting into trouble at school,

involved in petty criminal activity, and he was

only 13 when he was sent to live in a group

home for troubled youth.

Ali ran away from the group home within

months and spent years bouncing around the

foster care system, ultimately abandoning foster

placements in favor of the streets. He lived in

a number of different homes and was institutionalized at one point after he barricaded

himself in a room in response to harassment from other teens.

38

This “blame the victim”

attitude is one that a number of service providers said is all too common among agencies

working with LGBT homeless youth.

Factors just like those in Ali’s life have an influence on intrafamily conflict, which is a

primary reason why LGBT youth disproportionately become homeless. When Ali was

13, he began working as a prostitute, making $40 or $60 from each client. He said it

made him feel wealthy “like Donald Trump,” though in reality he was barely surviving.

His experience reflects that of many homeless LGBT youth who engage in survival sex to

secure shelter or a meal.

WHAT IS THE DEFINITION OF

“HOMELESS YOUTH?”

The definition of homeless youth includes youth who

are living on the streets or in shelters, runaways who

have voluntarily left a dangerous or otherwise unde-

sirable home environment, “throwaways” whose

parents or guardians have kicked them out and ado-

lescents who have aged out of foster care or state

custody and have nowhere to go.

A number of different definitions of “youth” and

“homeless” are used by government agencies and,

as we discuss in this publication, this type of incon-

sistency makes it difficult to optimize service delivery

or determine the level of funds really needed to serve

the population.

Many studies of homeless youth do not include a

detailed breakdown of those surveyed, disregard-

ing whether they are on the streets or temporarily

housed. We provide this explanation to ensure the

reader is aware of the inconsistencies in the system

and the attendant literature. Our policy recommenda-

tions address some of the problems that emerge from

these inconsistencies.

34 For more information, see www.safehorizon.org.

35 Foley, D. (1996, February). AIDS education for teen prostitutes - New York Peer AIDS Education Coalition. The Progressive. p.19.

36 Carter, C. (1999, August 28). A life and death on NYC streets. Retrieved September 27, 2006, from http://www.aliforneycenter.org/ap-

article.html

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

10

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

This dizzying spiral of lost opportunities is not an easy one to escape. Ali tried. After living

at Streetwork for a year, he, like many other displaced youth, tried to reunite with his

family. Research suggests that family involvement in the lives of homeless youth can have

a positive impact, but all too often is impossible or simply absent. Ali’s effort lasted no

more than a few days and he landed back at the agency. The fact that

he identified as transgender and gay was just one of the issues that

made reunification harder. Ali’s life and death is a tragic example of

what can happen when LGBT youth are forced onto the streets as

their only escape from a bad home or shelter environment.

This report comprehensively addresses some basic questions. How

many LGBT homeless youth are there? And, what are the specific

experiences of LGBT youth in the existing shelter and homeless

services system? We summarize the history of the federal response to

youth homelessness, highlighting the federal programs and funding

streams available to homeless youth services providers as well as the

impact on LGBT homeless youth of recent efforts to fund faith-

based services.

We provide a comprehensive literature review of the academic research on critical issues

affecting this population, including mental health issues, substance abuse and risky

sexual behavior. In order to put a face to all of the research and data we summarize, we

also include profiles of and quotes from LGBT homeless youth. Many were collected

through focus groups we conducted at homeless LGBT youth services providers around

the country. We also partnered with five services providers, who have written sections of

this report that detail model service delivery programs they have developed for providing

a wide variety of services to LGBT homeless youth. Finally, in consultation with a number

of youth advocacy organizations, we conclude with a series of policy recommendations

that can help to curb this epidemic of LGBT youth homelessness.

This publication is a

reference document

for the causes and

consequences of LGBT

youth homelessness,

and provides a series of

policy recommendations

that can help to curb

this epidemic.

11

How many LGBT

homeless youth are

there and why do they

become homeless?

Providing an accurate answer to the question of how many lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans-

gender (LGBT) homeless youth there are is no easy task. Given the multiple definitions

of homelessness and the variety of subpopulations that might or might not be included

in any count, it is not possible to provide the specific number of homeless LGBT youth

in the United States at any given point in time. Should such

a count include only LGBT youth on the streets who literally

lack a roof over their heads each night? Should it also include

any youth who is in an out-of-home care situation, such as

an emergency shelter or transitional living program? What

about LGBT youth who are “couch surfing,” moving from one

friend’s home to another to avoid staying on the streets?

39

One of the constant concerns surrounding the kind of

survey research that is used throughout this study to learn

about homeless youth is that respondents are self-reporting

in response to posed questions. They might lie, exaggerate,

or exclude important information out of fear. Whitbeck and

Hoyt conducted a study of homeless youth and their families to

address this concern.

40

They interviewed a sample of parents or

caregivers in addition to homeless youth themselves about the

reasons for family breakdown. They found that these second

interviews generally back up youth claims that they are escaping

abusive, low-supervision spaces where parental warmth is lacking. It is surprising that

a parent or caregiver would confirm the reality as presented by their child rather than

seeking to deny problems or to transfer responsibility to the child.

Ideally, in order to provide appropriate services, we need to know the total homeless

count: young and old; LGBT and straight; urban, suburban and rural. We can then

assess how many youth on any given night are experiencing temporary or long-term

homelessness, defined as absence from what might be labeled their permanent home.

As we will discuss shortly, conducting such a count is a process laden with all sorts of

methodological and political obstacles. However, around the country local organizations

39 Glassman, A. (2006, January 20). Center will reach out to homeless youth this summer. Gay People’s Chronicle. p.3.

40 Whitbeck, L. B. & Hoyt, D.R. (1999). Nowhere to grow: Homeless and runaway adolescents and their families. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

A note on acronyms

The reader should also bear in mind

that as time has passed, the acronyms

used to describe this community

have expanded. As elsewhere in

this report, we use LGBT to describe

the community we are interested

in when we are talking broadly or

citing literature that also uses this

broad definition. However, much of

the literature makes no reference to

bisexual or transgender youth, and

where that is the case we reference

only the specific community that an

author identifies.

12

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

have conducted counts that enable us to provide at least some idea of how many LGBT

youth are experiencing homelessness in the United States.

Regardless of the specific numbers, there is a growing awareness that the number of

LGBT youth experiencing homelessness is on the rise from already high figures.

41

This could be due in part to the fact that youth are now coming out in their

early teens,

42

with one recent report citing an average of 13 years old.

43

Another

contributing factor is the scarcity of care options once a child has left home.

When LGBT youth leave home, voluntarily or otherwise, they are more likely than

their heterosexual peers to end up living on the streets rather than in a state care

facility.

44

With foster care the preferred destination, social workers try to find a

temporary home for each youth, but

…there is typically a dearth of available foster families to begin with, and few are

willing to work with young people who have emotional or behavioral problems. Fewer

still are interested in fostering LGBT youths, many of whom

arrive with emotional and behavioral issues as a result of the

homophobia they’ve endured.

45

For those who cannot be placed in foster homes, group homes may

be the next best choice, though anti-LGBT attitudes are common

there as well.

46

Often, they are sufficiently hostile that youth would

rather live on the streets.

To determine an estimate of the LGBT homeless youth population,

we first need estimates of the number of homeless or runaway

youth overall. Thompson et al., in their study analyzing Runaway

and Homeless Youth Management Information System (RHYMIS)

data, cite estimates of 575,000 to 1,000,000 youth who run away or

are forced to leave their parental home in any given year.

47

One estimate set the number

nationwide at 1.3 million,

48

while a 1998 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development report suggested that 1.6 million youth are homeless or run away each

year.

49

By surveying respondents to the National Health Interview Study, Ringwalt et al.

estimate that 5 percent of youth, or approximately one million, experience homelessness

in any given year.

50

Whitbeck and Simons estimate that one child in eight will run away

at some point before they turn 18, and fully 40 percent of these do not return to the place

from which they ran away.

51

Few cities have conducted a large scale count. As of the late 1990s, advocates estimated

Ideally, in order to

provide appropriate

services, we need

to know the total

homeless count:

young and old; LGBT

and straight; urban,

suburban and rural.

41 Thompson, S. J. et. al. (2001).

42 Kim, E. K. (2006, July 3). Many gay teens are coming out at earlier ages. St.Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved September 1, 2006, from

http://www.fortwayne.com/mld/newssentinel/living/14957350.htm

43 PlanetOut gay & lesbian news. (2006, October 11). Average coming-out age now 13, survey finds. Author. Retrieved October 12, 2006,

from http://www.planetout.com/news/article.html?2006/10/11/4

44 Berger, C. (2005). What becomes of at-risk gay youths? The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide.

45 Berger, C. (2005). p.24. See also Sullivan, R. T. (1994). Obstacles to effective child welfare service with gay and lesbian youths. Child

Welfare, 73(4).

46 Berger, C. (2005). p.24.

47 Thompson, S. J. et. al. (2001).

48 Sanchez, R. (2004, December 20). Facing up to homeless youths. Denver Post. p.A1.

49 Robertson, M. J. & Toro, P. A. (1998).

50 Ringwalt, C. L., Greene, J. M., Robertson, M. & McPheeters, M. (1998). The prevalence of homelessness among adolescents in the

United States. American Journal of Public Health, 88(9). p.1327.

51 Whitbeck, L. B. & Simons, R. L. (1990). Life on the streets: The victimization of runaway and homeless adolescents. Youth and Society, 22(1).

13

that upwards of 20,000 homeless youth were living on the streets of New York,

52

while

a 2002 report suggested the number stood somewhere between 15,000 and 20,000.

53

In

2004, the U.S. Conference of Mayors suggested that unaccompanied youth make up 5

percent of the total urban homeless population, up from 3 percent in 1998.

54

Ringwalt et al.’s study also addresses race and ethnicity, citing one national study that

found no demographic differences between homeless people and the general population.

55

However, other studies have suggested that racial and ethnic minorities may actually be

overrepresented in the homeless youth population.

56

When it comes to counting or

estimating the number of LGBT youth experiencing homelessness, the existing literature

provides a wide range of figures. Despite this variance, there is a consensus that LGBT

youth represent a significant proportion of the homeless youth population.

In 1985, the National Network of Runaway and Youth Services (now the National

Network for Youth) estimated that only 6 percent of homeless adolescents identified as

gay or lesbian.

57

They have subsequently revised this estimate upwards to a range of 20

percent to 40 percent.

58

Other studies from the early to mid-1990s reported that 3 percent

to 10 percent of homeless youth were gay or lesbian. However, more recent studies and

ample anecdotal evidence from social service professionals suggest that the proportion of

LGBT youth in the overall homeless youth population is significantly higher than their

proportion in the U.S. population as a whole.

59

Clatts et al. estimate that among combined homeless and street-involved popula-

tions,

60

35 percent are LGBT, while among street youth only, the figure might

climb as high as 50 percent.

61

A study of unaccompanied homeless youth in Illinois

reported a statewide figure of 14.8 percent who identified as LGB, “questioning” or

“something else.” According to a report published in 2005, in the city of Chicago and

immediately surrounding Cook County, the rate for these groups was 23.1 percent

and 22.4 percent respectively.

62

In Decatur, Illinois, a youth group surveyed homeless youth and found that 42 percent

identified as LGB, while service providers in Los Angeles estimated that between 25

and 35 percent of homeless youth there are lesbian or gay.

63

In Portland, Oregon, one

52 Holloway, L. (1998, July 18). Young, restless and homeless on the piers; Greenwich Village reaches out to youths with plan for shelter

and services. New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2005, from http://query.nytimes.com/gst/health/article-printpage.html?res=

9C05E5DE1330F93BA257

53 Nolan, T. (2004). Couch-surfers: Invisible homeless youth. In the Family. p.21-22.

54 U.S.Conference on Mayors (2004). A status report on hunger and homelessness in American’s cities: 2004. U.S. Conference of Mayors.

Retrieved September 22, 2006, from www.sodexhousa.com/HungerAndHomelessnessReport2004.pdf

55 Ringwalt, C. L. et. al. (1998).

56 McCaskill, P. A., Toro, P. A. & Wolfe, S. M. (1998). Homeless and matched housed adolescents: A comparative study of psychopa-

thology. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27(3). Cited in Robertson, M. J. & Toro, P. A. (1998).

57 National Network of Runaway and Youth Services [now the National Network for Youth]. To whom do they belong? A profile of America’s

runaway and homeless youth and the programs that help them. Washington, DC: Author.

58 Cited in Dylan Nicole, d. K. (2004). City enters partnership to assist lesbian and gay homeless youth. Nation’s Cities Weekly, 27(10).

59 Task Force Policy Institute analysis of the available representative data suggests that 3 to 5 percent of the U.S. population identifies as

lesbian or gay..

60 Street-involved youth are those who have a home to which they can and often do return at night. However, for a multitude of reasons

they choose to involve themselves with youth living on the streets, often becoming accepted members of the community of youth.

In New York City, for example, there are youth who skip school and/or stay out late at night to hang out with homeless youth on the

Hudson River piers.

61 Clatts, M. J. et. al. (1998). Cited in Dame, L. (2004).

62 Johnson, T. P. & Graf, I. (2005, December). Unaccompanied homeless youth in Illinois: 2005. Chicago, IL: Survey Research Laboratory

- University of Illinois Chicago. p.46.

63 Cited in Truong, J. (2004). Homeless LGBT youth and LGBT youth in foster care: Overview. The Safe Schools Coalition. Retrieved June 3,

2005, from http://www.safeschoolscoalition.org/RG-homeless.html

How many, and why?

14

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

homeless youth service provider estimated that their LGB clientele climbed from 20

percent

64

to approximately 30 percent of youth between 1993 and 1994.

65

This same

proportion was noted by Rob McDonald, a project coordinator with a welfare agency

in Ottawa, Canada.

66

The city of Seattle’s Commission on Children and Youth found that approximately 40

percent of homeless youth identified as lesbian, gay or bisexual.

67

Unfortunately, because

of the fear many young people have about acknowledging to themselves or others during

a survey that they are lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or transgender,

these figures are likely an undercount of the true proportion of LGBT

homeless youth. What is absolutely clear is that regardless of the

actual number of LGBT people in the overall population, a dispro

-

portionate share of the nation’s homeless youth identify as LGBT.

While the estimates we cite are biased toward large cities, youth home

-

lessness, LGBT or otherwise, is not just an urban problem. Ringwalt et

al. confirm that this is a problem in rural and suburban America too.

Among street youth, however, there is a clear bias towards major West

and East Coast cities.

68

While some may run away to certain places

for cultural reasons, there is no literature addressing this specifically.

However, most youth who run away do not run far. Van Houten and Golembiewski found

that 72 percent of their survey respondents at 17 runaway and homeless youth programs

nationwide were from the immediate geographic area.

69

In the case of LGBT street youth in particular, conversations with service providers suggest

that there is a somewhat romanticized notion of leaving the homophobic hometown

behind to find acceptance in New York City, Los Angeles or San Francisco.

70

BARRIERS TO A MORE ACCURATE COUNT

There is a long history in the United States of counting people in order to make a variety

of policy determinations. After all, if government is to appropriately allocate resources

and services, then it needs some idea of who people are and where they live. The U.S.

Constitution mandates that the federal government conduct a Census every decade. The

results of that decennial Census have a profound impact on every part of the public policy

process, from how many dollars a particular state receives of a block grant to address drug

treatment, to how many Congressional House districts each state is allocated.

In the United States, Census forms are mailed to every household in the nation and

Census Bureau enumerators follow up with households for which no form has been

returned. No Census methodology is perfect, and for many reasons it is impossible to

count everyone. While the process is time-consuming and there are naturally exceptions

The proportion of

LGBT youth in the

overall homeless youth

population is significantly

higher than their

proportion in the U.S.

population as a whole.

64 Ibid.

65 Krisberg, K. (2002). Oregon clinic increases health care access for homeless youth. Nation’s Health, 32(7).

66 Truong, J. (2004).

67 Dylan Nicole, d. K. (2004).

68 Cited in Robertson, M. J. & Toro, P. A. (1998). p.4.

69 Ibid. p.28.

70 Conversations between the author and a number of service providers around the United States.

15

to the rule, it is relatively easy on any given day to count the number of people who live in

a given apartment. Extrapolate that reality across the country, and the government is able

to obtain a reasonably accurate nationwide count of the most stable sectors of society.

However, there are many people who are not as easily reached, particularly people

experiencing homelessness.

71

Finding an appropriate time of year to do a count means

factoring in weather and a number of regional variables that might impact the success

of a count in a particular location on any given day. Additionally, many homeless

youth will consciously avoid anyone who looks like an authority figure. Many people

experiencing homelessness, including youth, tend to be constantly mobile or congregate

in areas where access is not always easy, such as abandoned buildings.

72

,

73

There are

other obstacles: the number of people needed to conduct such a count is large, and

the training required to ensure consistency across all areas would be complex. But the

consequences of not finding a solution to this lack of critical data are far worse than

those of overcoming logistical difficulties.

An accurate count of people experiencing homelessness is crucially important because

many services for this population are provided using federal funds. The allocation of

federal funds is often based on population counts conducted during the Census. Without

an accurate count of how many people are experiencing homelessness or living on the

streets in any city, it is difficult to confirm crucial characteristics of the population

experiencing homelessness or to secure necessary increases in funding. This gap in data

inevitably impairs service delivery.

74

Politics may also play into these kinds of decisions. Some believe that the lack of an

accurate count of the nation’s homeless population provides an excuse for politicians and

public policy administrators to avoid dealing with the issue comprehensively. Advocates

for homeless people and politicians have often clashed over how many people experience

homelessness and the funds needed to serve them appropriately. Some claim that an

accurate count is not possible, which if true means that there is at best only a rough

relationship between need and resources. In the words of one homeless advocate, “They

don’t want to find them because then they would have to provide services for them.”

75

A national and representative count of people experiencing homelessness, including

those who are LGBT youth, would enable unprecedented targeting of services and funds.

The benefits of having such a count, along with the resulting data, would move us beyond

a situation often faced today when advocates promote particular populations’ needs and

service providers seek funding for those populations but lack the data to justify it. For

example, because our information about homeless LGBT youth is so uncertain, it is often

difficult to persuade policy-makers to allocate scarce resources to serve this population.

When funds are requested for providing services to LGBT homeless youth, politicians

and policymakers ask for data to help justify the request. Obtaining an accurate nation

-

71 Ringwalt, C. L., Greene, J. M., Robertson, M. & McPheeters, M. (1998). The prevalence of homelessness among adolescents in the

United States. American Journal of Public Health, 88(9).

72 Ibid.

73 For further discussion of problematic aspects of conducting a count of people experiencing homelessness, see Seper, C. (2006, January

17). Counting gay youths who are homeless. Cleveland.com. Retrieved January 17, 2006, from www.cleveland.com

74 Ringwalt, C. L. et. al. (1998). p.1325.

75 Kihara, D. (1999, August 24). Giuliani’s suppressed report on homeless youth. The Village Voice. 44(33). Retrieved October 2, 2006,

from http://www.villagevoice.com/news/9933,kihara,7688,5.html

How many, and why?

16

Homelessness

LGBT Youth

wide count that includes information about sexual orientation and gender identity would

finally provide irrefutable evidence of the significant scale of homelessness and, more

specifically, the fact that LGBT homeless youth are disproportionately represented among

the overall homeless youth population. A proper count could help advocates around the

country persuade federal, local and state agencies to increase funding to provide safe

space

76

and adequate support services for these youth. It would also enable advocacy

organizations to point to specific data demonstrating their own communities’ needs.

WHY DO YOUTH BECOME HOMELESS?

The reasons for deciding to leave home or for being thrown out are almost as varied as the

number of young people who find themselves homeless in any given year. Still, simply put,

conflict at home is the primary cause of a youth becoming homeless. Precipitating issues

might involve educational problems, drug or alcohol abuse, communication breakdown,

religious conflict or a desire for independence. Conflict over a youth’s sexual orientation

or gender identity can all too often be the deciding factor in landing a young person on

the streets or in out-of-home care.

77

Regardless of the ultimate reason, youth face short

and long term consequences. Critical developmental processes are usually affected, as

Rosenheck et al. make clear:

Consolidation of one’s identity, separation from one’s parents and preparation

for independence are key developmental tasks of adolescence and critical for

becoming a well-functioning adult in our society. Most adolescents prepare

for this transition to adulthood in their homes and school… these [homeless]

adolescents are generally ill-equipped for independent living and many become

easy prey for predators on the streets.

78

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND GENDER IDENTITY ISSUES

According to one study, 50 percent of gay males experienced a nega-

tive parental reaction when they came out and 26 percent of those

disclosures were met with a demand that the youth leave home.

79

In the case of Kurt Dyer, this meant packing his entire life into six

trash bags at the age of 16 and moving in with a friend’s family.

Kurt was lucky; as he puts it, the biggest choice he had to make after

leaving was the question his friend’s parents posed: “What color do

you want to paint your new room?”

80

Obviously Kurt’s experience

is not typical, but his determination to succeed in the long term is

common. We discuss the resiliency of homeless LGBT youth later in

Twenty-six percent of all

LGBT disclosures were

met with a demand that

the youth leave home.

In the case of Kurt Dyer,

this meant packing his

entire life into six trash

bags and moving in

with a friend’s family.

76 When we say safe space, we mean a space where homeless youth can go and safely receive services and support without fear of discrimi-