w

Language & Social Justice

in the United States

Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley &

Guadalupe Valdés, guest editors

with Anne Curzan · Robin M. Queen

Kristin VanEyk · Rachel Elizabeth Weissler

Wesley Y. Leonard · Julia C. Fine

Jessica Love-Nichols · Bernard C. Perley

Jonathan Rosa · Nelson Flores

Aris Moreno Clemons · Jessica A. Grieser

Joyhanna Yoo · Cheryl Lee · Andrew Cheng

Anusha Ànand · H. Samy Alim · John Baugh

Sharese King · John R. Rickford

Norma Mendoza-Denton

Dædalus

Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Summer 2023

Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Dædalus

“Language & Social Justice in the United States”

Volume 152, Number 3; Summer 2023

Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley & Guadalupe Valdés, Guest Editors

Phyllis S. Bendell, Editor in Chief

Peter Walton, Associate Editor

Key Bird, Assistant Editor

Inside front cover: The photos on the inside front and back covers, provided by the authors of

this volume of Dædalus, represent the rich and varied ways that, in the words of Toni Morrison,

“we do language.”

(top row) Basket weavers in Village Tindomsolibgo (Upper East Region, Ghana) do call and

response work songs, 2021. Photo courtesy of Walt Wolfram.

(middle row, left) Wesley Y. Leonard in Miami Tribe of Oklahoma headquarters, standing next

to a display of myaamia ribbonwork that also has the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma seal, June 2023.

Photo courtesy of Wesley Y. Leonard. (right, upper) Black deaf signers demonstrate some of

the characteristics of Black ASL (American Sign Language) at Gallaudet University in Washing-

ton, D.C. Photo courtesy of Walt Wolfram. (right, lower) The Eastern Band of Cherokee immer-

sion school, New Kituwah Academy, Cherokee, North Carolina, 2014, as featured in the Emmy

award–winning film First Language: The Race to Save Cherokee. Photo courtesy of Walt Wolfram.

(bottom row) Sophomores at Sequoia High School in Redwood City, California, work with

Jonathan Rosa in Stephanie Weden’s class, February 2019. Photo by Elisa Niño-Sears, courtesy of

Jonathan Rosa.

Contents

5 Language & Social Justice in the United States: An Introduction

Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley & Guadalupe Valdés

18 Language Standardization & Linguistic Subordination

Anne Curzan, Robin M. Queen, Kristin VanEyk &

Rachel Elizabeth Weissler

36 Addressing Linguistic Inequality in Higher Education:

A Proactive Model

Walt Wolfram

52 Social Justice Challenges of “Teaching” Languages

Guadalupe Valdés

69 Refusing “Endangered Languages” Narratives

Wesley Y. Leonard

84 Climate & Language: An Entangled Crisis

Julia C. Fine, Jessica Love-Nichols & Bernard C. Perley

99 Rethinking Language Barriers & Social Justice from a

Raciolinguistic Perspective

Jonathan Rosa & Nelson Flores

115 Black Womanhood: Raciolinguistic Intersections of Gender,

Sexuality & Social Status in the Aftermaths of Colonization

Aris Moreno Clemons & Jessica A. Grieser

130 Asian American Racialization &

Model Minority Logics in Linguistics

Joyhanna Yoo, Cheryl Lee, Andrew Cheng & Anusha Ànand

147 Inventing “the White Voice”: Racial Capitalism,

Raciolinguistics & Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies

H. Samy Alim

167 Linguistic Profiling across International

Geopolitical Landscapes

John Baugh

178 Language on Trial

Sharese King & John R. Rickford

194 Currents of Innuendo Converge on an

American Path to Political Hate

Norma Mendoza-Denton

212 Liberatory Linguistics

Anne H. Charity Hudley

Dædalus was founded in 1955 and established as a quarterly in 1958. Its

namesake was renowned in ancient Greece as an inventor, scientist, and unriddler

of riddles. The journal’s emblem, a maze seen from above, symbolizes the aspira-

tion of its founders to “lift each of us above his cell in the labyrinth of learning in

order that he may see the entire structure as if from above, where each separate

part loses its comfortable separateness.”

The American Academy of Arts & Sciences, like its journal, brings together

distinguished individuals from every field of human endeavor. It was chartered

in 1780 as a forum “to cultivate every art and science which may tend to advance

the interest, honour, dignity, and happiness of a free, independent, and virtuous

people.” Now in its third century, the Academy, with its more than five thousand

members, continues to provide intellectual leadership to meet the critical chal-

lenges facing our world.

Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Dædalus

Nineteenth-century depiction of a Roman mosaic labyrinth, now lost,

found in Villa di Diomede, Pompeii

Dædalus Summer 2023

Issued as Volume 152, Number 3

© 2023 by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

Editorial offices: Dædalus, American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 136 Irving Street,

Cambridge MA 02138. Phone: 617 576 5085. Fax: 617 576 5088. Email: [email protected].

Library of Congress Catalog No. 12-30299.

Dædalus publishes by invitation only and assumes no responsibility for unsolicited man-

uscripts. The views expressed are those of the author(s) of each essay, and not necessarily

of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

Dædalus (ISSN 0011-5266; E-ISSN 1548-6192) is published quarterly (winter, spring,

summer, fall) by The MIT Press, One Broadway, Floor 12, Cambridge MA 02142-1189, for

the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. An electronic full-text version of Dædalus is

available from amacad.org/daedalus and from The MIT Press.

Dædalus is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0

International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. For allowed uses under this license, please visit

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0.

Members of the American Academy please direct all questions and claims to

Advertising inquiries may be addressed to Marketing Department, MIT Press Journals,

One Broadway, Floor 12, Cambridge MA 02142-1189. Phone: 617 253 2866. Fax: 617 253

1709. Email: [email protected].

To request permission to photocopy or reproduce content from Dædalus, please contact

the Subsidiary Rights Manager at MIT Press Journals, One Broadway, Floor 12, Cambridge

MA 02142-1189. Fax: 617 253 1709. Email: [email protected].

Corporations and academic institutions with valid photocopying and/or digital licenses

with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) may re produce content from Dædalus under

the terms of their license. Please go to www.copyright.com; CCC, 222 Rosewood Drive,

Danvers MA 01923.

Printed in the United States by The Sheridan Press, 450 Fame Avenue, Hanover PA 17331.

Postmaster: Send address changes to Dædalus, One Broadway, Floor 12, Cambridge MA

02142-1189. Periodicals postage paid at Boston MA and at additional mailing offices.

The typeface is Cycles, designed by Sumner Stone at the Stone Type Foundry of Guinda

CA. Each size of Cycles has been sep arately designed in the tradition of metal types.

5

© 2023 by Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley & Guadalupe Valdés

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license

https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_e_02014

Language & Social Justice in the

United States: An Introduction

Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley &

Guadalupe Valdés

I

n recent decades, the United States has witnessed a noteworthy escalation of

academic responses to long-standing social and racial inequities in its society.

In this process, research, advocacy, and programs supporting diversity and in-

clusion initiatives have grown. A set of themes and their relevant discourses have

now developed in most programs related to diversity and inclusion; for example,

current models are typically designed to include a range of groups, particularly

reaching people by their race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, religious affiliation,

gender, and other demographic categories. Unfortunately, one of the themes typ-

ically overlooked, dismissed, or even refuted as necessary is language. Further-

more, the role of language subordination in antiracist activities tends to be treat-

ed as a secondary factor under the rubric of culture. Many linguists, however, see

language inequality as a central or even leading component related to all of the

traditional themes included in diversity and inclusion strategies.

1

In fact, writer

and researcher Rosina Lippi-Green observes that “Discrimination based on lan-

guage variation is so commonly accepted, so widely perceived as appropriate, that

it must be seen as the last back door to discrimination. And the door stands wide

open.”

2

Even academics, one of the groups that should be exposed to issues of compre-

hensive inclusion, have seemingly decided that language is a low-priority issue. As

noted in a 2015 article in The Economist:

The collision of academic prejudice and accent is particularly ironic. Academics tend

to the centre-left nearly everywhere, and talk endlessly about class and multicultural-

ism. . . . And yet accent and dialect are still barely on many people’s minds as deserving

respect.

3

As such, as the editors of this collection, we have commissioned thirteen essays

that address specific issues of language inequality and discrimination, both in their

own right and directly related to traditional themes of diversity and inclusion.

6 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language & Social Justice in the United States: An Introduction

Recent issues of Dædalus have addressed immigration, climate change, access

to justice, inequality, and teaching in higher education, all of which relate to lan-

guage in some way.

4

The theme of the Summer 2022 issue is “The Humanities in

American Life: Transforming the Relationship with the Public.” As an extension of

that work, the essays in this volume focus on a humanistic social science approach

to transforming our relationship with language both in the academy and at large.

There is a growing inventory of research projects and written collections that

consider issues of language and social justice, including dimensions such as racio-

linguistics, linguistic profiling, multilingual education, gendered linguistics, and

court cases that are linguistically informed. Those materials cover a comprehen-

sive range of language issues related to social justice. The collection of essays in

this Dædalus volume is unique in its breadth of coverage and extends from issues

including linguistic profiling, raciolinguistics, and institutional linguicism to

multi lingualism, language teaching, migration, and climate change. The authors

are experts in their respective areas of scholarship, who combine strong research

records with extensive engagement in their topics of inquiry.

T

he initial goal of this Dædalus issue is to demonstrate the vast array of so-

cial and political disparity manifested in language inequality, ranging from

ecological conditions such as climate change, social conditions of inter-

and intralanguage variation, and institutional policies that promulgate the notion

and the stated practice of official languages and homogenized, monolithic norms

of standardized language based on socially dominant speakers. These norms are

socialized overtly and covertly into all sectors of society and often are adopted

as consensus norms, even by those who are marginalized or stigmatized by these

distinctions. As linguist Norman Fairclough notes in Language and Power, the ex-

ercise of power is most efficiently achieved through ideology-manufacturing

consent instead of coercion.

5

Practices that appear universal or common sense

often originate in the dominant class, and these practices work to sustain an un-

equal power dynamic. Furthermore, there is power behind discourse because the

social order of discourses is held together as a hidden effect of power, such as stan-

dardization and national/official languages, and power in discourse as strategies

of discourse reflect asymmetrical power relations between interlocutors in sets of

routines, such as address forms, interruptions, and a host of other conversational

routines. In this context, the first step in addressing these linguistic inequalities

is to raise awareness of their existence, since many operate as implicit bias rather

than overt, explicit bias recognized by the public.

Unfortunately, and somewhat ironically, higher education has been slow in

this process; in fact, several essays in this collection show that higher education

has been an active agent in the reproduction of linguistic inequality at the same

time that it advocates for equality in many other realms of social structure.

6

Two

152 (3) Summer 2023 7

Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley & Guadalupe Valdés

essays in particular explore underlying notions of standardization and the use of

language in social presentation and argumentation. The essays also address lan-

guage rights as a fundamental human right. In “Language Standardization & Lin-

guistic Subordination,” Anne Curzan, Robin M. Queen, Kristin VanEyk, and Rachel

Elizabeth Weissler discuss how ideologies about standardized language circulate

in higher education, to the detriment of many students, and they include a range

of suggestions and examples for how to center linguistic justice and equity within

higher education.

Curzan and coauthors give us an important overview of language stan-

dardization:

We have suggested some solutions to many of the issues we’ve highlighted in this es-

say; however, implementing solutions in a meaningful way first requires recognition

of how important language variation is for our everyday interactions with others. Sec-

ond, implementing solutions depends on recognizing how our ideas about language

(standardized or not) can pose a true barrier to meaningful change. Such recognition

includes the understanding that much of what we think about language often stands

as a proxy for what we think about people, who we are willing to listen to and hear, and

who we want to be with or distance ourselves from.

7

In “Addressing Linguistic Inequality in Higher Education: A Proactive Model,”

Walt Wolfram describes a proactive “campus-infusion” program that includes

activities and resources for student affairs, academic affairs, human resources,

faculty affairs, and offices of institutional equity and diversity. Wolfram’s essay

shows directly and specifically how academics aren’t always the solution but, as a

whole, are complicit in linguistic exclusion. He writes:

A casual survey of university diversity statements and programs indicates that a) there

is an implicitly recognized set of diversity themes within higher education and b) it

traditionally excludes language issues.

8

Topics related to race, ethnicity, gender, reli-

gion, sexual preference, and age are commonly included in these programs, but lan-

guage is noticeably absent, either by explicit exclusion or by implicit disregard. Ironi-

cally, issues of language intersect with all of the themes in the canonical catalog of di-

versity issues.

9

The absence of systemic language considerations from most diversity and in-

clusion programs and their limited role in antiracist initiatives is a major con-

cern for these programs, since language is a critical component for discrimination

among the central themes in the extant canon of diversity. Language is an active

agent in discrimination and cannot be overlooked or minimized in the process.

Some of the essays in this volume of Dædalus address the sociopolitical dom-

inance of a restricted set of languages and its impact on the lives of speakers of

devalued languages. The authors of these essays consider the effects of climate,

8 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language & Social Justice in the United States: An Introduction

social, educational, legal, and political dissonance confronted by speakers of non-

dominant languages. They also show how the metaphors of “disappearance” and

“loss” obscure the colonial processes responsible for the suppression of Indig-

enous languages. People who speak an estimated 90 percent of the world’s lan-

guages have now been linguistically and culturally harmed due to the increasing

dominance of a selected number of “world languages” and changes in the phys-

ical and topographical ecology. The authors describe the implications of this ex-

tensive language subjugation and endangerment and the consequences for the

speakers of these languages. Both physical and social ecology are implicated in

this threat to multitudes of languages in the world.

Linguistics in general, and sociolinguistics in particular, has a significant his-

tory of engagement in issues of social inequality. From the educational controver-

sies over the language adequacy of marginalized, racialized groups of speakers in

the 1960s, as in linguist William Labov’s A Study of Non-Standard English, to ideo-

logical challenges to multilingualism and the social and cultural impact of the de-

valuing of the world’s languages, as described in the essays by Wesley Y. Leonard,

Guadalupe Valdés, and Julia C. Fine, Jessica Love-Nichols, and Bernard C. Perley,

the role of language is a prominent consideration in the actualization and dispen-

sation of social justice.

10

In addition, this collection addresses areas of research that are complementa-

ry to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ 2017 report by the Commission

on Language Learning, America’s Languages: Investing in Language Education for the

21st Century.

11

In spite of the long-term presence of the teaching of languages other

than English in the American educational system, concern over “world language

capacity” has surfaced periodically over a period of many years because of the

perceived limitations in developing functional additional language proficiencies.

The consensus view (as in Congressman Paul Simon’s 1980 report The Tongue-Tied

American) has been that foreign/world language study in U.S. schools is generally

unsuccessful, that Americans are poor language learners, and that focused atten-

tion must be given to the national defense implications of these language limita-

tions.

12

In the 2017 Language Commission report, foreign/world language study is

presented as 1) critical to success in business, research, and international relations

in the twenty-first century and 2) a contributing factor to “improved learning out-

comes in other subjects, enhanced cognitive ability, and the development of em-

pathy and effective interpretive skills.”

13

The Academy’s report presents information about languages spoken at home

by U.S. residents (76.7 percent English, 12.6 percent Spanish). It also includes a

graphic illustrating the prevalence of thirteen other languages (including Chi-

nese, Hindi, Filipino and Tagalog, and Vietnamese) commonly spoken by 0.13

percent to 0.2 percent of the population, as well as a category identified as all

other languages (a small category comprising 2.2 percent of residents of the Unit-

152 (3) Summer 2023 9

Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley & Guadalupe Valdés

ed States).

14

The report focuses on languages–rather than speakers–and rec-

ommends: 1) new activities that will increase the number of language teachers,

2) expanded efforts that can supplement language instruction across the educa-

tion system, and 3) more opportunities for students to experience and immerse

themselves in “languages as they are used in everyday interactions and across all

segments of society.” It also specifically mentions needed support for heritage lan-

guages so these languages can “persist from one generation to the next,” and for

targeted programming for Native American languages.

15

While it effectively interrupted the monolingual, English-only ideologies that

permeate ideas on language in the United States, the conceptualization of language

undergirding the report needs to be greatly expanded. The report focuses on devel-

oping expertise in additional language acquisition as the product of deliberative

study. For example, in the case of heritage languages (defined as those non-English

languages spoken by residents of the United States), the report highlights efforts

such as the Seal of Biliteracy. Through this effort (now endorsed by many states

around the country), high school students who complete a sequence of established

language classes and pass a state-approved language assessment can obtain an offi-

cial Seal of Biliteracy endorsement. Unfortunately, the series of courses and the as-

sessments required to obtain the Seal are only available in a limited number of lan-

guages. The report mentions other efforts, including dual language immersion pro-

grams, yet it does not recognize family- and community- gained bilingualism and

biliteracy. Notably, the report specifically laments what are viewed as limited literacy

abilities of heritage language speakers and recommends making available curricula

specially designed for heritage language learners and Native American languages.

The view of language that the report is based on is a narrow one and does not

represent the linguistic realities of the majority of bilingual and multilingual stu-

dents. In her contribution to this volume, “Social Justice Challenges of ‘Teaching’

Languages,” Guadalupe Valdés “specifically problematize[s] language instruction

as it takes place in classroom settings and the impact of what I term the curricu-

larization of language as it is experienced by Latinx students who ‘study’ language

qua language in instructed situations.”

16

Valdés shows us how these specific issues

play out in what is typically viewed as the neutral “teaching” of languages. She

writes that challenges to

linguistic justice [result] from widely held negative perspectives on bi/multilingual-

ism and from common and continuing misunderstandings of individuals who use re-

sources from two communicative systems in their everyday lives. My goal is to high-

light the effect of these misunderstandings on the direct teaching of English.

17

In “Refusing ‘Endangered Languages’ Narratives,” Wesley Y. Leonard draws

from his experiences as a member of a Native American community whose lan-

guage was wrongly labeled “extinct”:

10 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language & Social Justice in the United States: An Introduction

Within this narrative, I begin with an overview of how language endangerment is de-

scribed to general audiences in the United States and critique the way it is framed and

shared. From there, I shift to an alternative that draws from Indigenous ways of know-

ing to promote social justice through language reclamation.

18

Leonard encourages us to directly refute “dominant endangered languages nar-

ratives” and replace the focus on the actors of harm in Indigenous communities

with a focus on the creativity and resolve of native scholars working to revitalize

native language and culture. As he states, the “ultimate goal of this essay is to pro-

mote a praxis of social justice by showing how language shift occurs largely as a

result of injustices, and by offering possible interventions.”

19

In “Climate & Language: An Entangled Crisis,” Julia C. Fine, Jessica Love-

Nichols, and Bernard C. Perley

note that these academic discourses–as well as similar discourses in nonprofit and

policy-making spheres–rightly acknowledge the importance of Indigenous thought

to environmental and climate action. Sadly, they often fall short of acknowledging

both the colonial drivers of Indigenous language “loss” and Indigenous ownership of

Indigenous language and environmental knowledge. We propose alternative framings

that emphasize colonial responsibility and Indigenous sovereignty.

20

Fine, Love-Nichols, and Perley present models of how language and climate are

intertwined. They write, “Scholars and activists have documented the intersec-

tions of climate change and language endangerment, with special focus paid to

their compounding consequences.” The authors “consider the relationship be-

tween language and environmental ideologies, synthesizing previous research on

how metaphors and communicative norms in Indigenous and colonial languages

influence environmental beliefs and actions.”

21

T

he essays in this volume profile a wide range of language issues related to

social justice, from everyday hegemonic comments to legislative policies

and courtroom testimony that depend on language reliability and the lin-

guistic credibility of witnesses who do not communicate in a mainstream Amer-

ican English variety. In 1972, the president of the Linguistic Society of America,

Dwight Bolinger, gave his presidential address titled “Truth is a Linguistic Ques-

tion” as a forewarning of the linguistic accountability of public reporting of na-

tional events. In his other work, he describes language as “a loaded weapon.”

Through these essays, we find both concepts to be true.

22

Over recent decades, the field of linguistics has developed a robust specializa-

tion in areas that pay primary attention to the application of a full range of legal

and nonlegal verbal, digital, and document communication that is at the heart of

equitable communication strategies. Language variation is also a highly politi-

152 (3) Summer 2023 11

Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley & Guadalupe Valdés

cized behavior, extending from the construct of a “standardized language” con-

sidered essential for writing and speaking to the use of language in negotiating

the administration of social and political justice. The essays on linguistic variation

and sociopolitical ideology, by Curzan and coauthors, Jonathan Rosa and Nelson

Flores, and H. Samy Alim, examine both the ideological underpinnings of con-

sensual constructs such as “standard” versus “nonmainstream” and their use in

the political process of persuasion and sociopolitical implementation.

23

The au-

thors in this section address key issues of language variation and language dis-

crimination that demonstrate the vitality of language in issues of social justice,

both independent of and related to other attributes of social justice. This mod-

el includes standardization in media platforms, as described in Rosa and Flores’s

essay, demonstrating the systemic othering of those who do not speak this variety

as their default dialect.

In “Rethinking Language Barriers & Social Justice from a Raciolinguistic Per-

spective,” Rosa and Flores show how “the trope of language barriers and the top-

pling thereof is widely resonant as a reference point for societal progress.”

We argue that by interrogating the colonial and imperial underpinnings of wide-

spread ideas about linguistic diversity, we can connect linguistic advocacy to broader

political struggles. We suggest that language and social justice efforts must link affir-

mations of linguistic diversity to demands for the creation of societal structures that

sustain collective well-being.

24

Rosa and Flores present and update their raciolinguistics model in current

spaces where race meets technology. With this emerging technology as a refer-

ence point, they demonstrate why “it is crucial to reconsider the logics that in-

form contemporary digital accent-modification platforms and the broader ways

that purportedly benevolent efforts to help marked subjects modify their language

practices become institutionalized as assimilationist projects masquerading as

assistance.” They also note that disability has always been part of the story–and

needs to be brought back to light–sharing that Mabel Hubbard and Ma Bell, who

were both influential on modern linguistic technology, were deaf women.

25

In “Black Womanhood: Raciolinguistic Intersections of Gender, Sexuality &

Social Status in the Aftermaths of Colonization,” Aris Moreno Clemons and Jessica

A. Grieser “call for an exploration of social life that considers the raciolinguistic

intersections of gender, sexuality, and social class as part and parcel of overarching

social formations.” They center the Black woman as the prototypical Other, her

condition being interpreted neither by conventions of race nor gender. As such, we

take “Black womanhood as the point of departure for a description of the neces-

sary intersecting and variable analyses of social life.” Clemons and Greiser “inter-

rogate the intersections of gender, sexuality, and social status, focusing on the ex-

periences of Black women who fit into and lie at the margins of these categories.”

12 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language & Social Justice in the United States: An Introduction

They highlight the work of semiotician Krystal A. Smalls, who “reveals a model

for how interdisciplinary reading across fields such as Black feminist studies, Black

anthropology, Black geographies, and Black linguistics can result in expansive and

inclusive worldmaking.”

26

In “Asian American Racialization & Model Minority Logics in Linguistics,”

Joyhanna Yoo, Cheryl Lee, Andrew Cheng, and Anusha Ànand “consider histori-

cal and contemporary racializing tactics with respect to Asians and Asian Ameri-

cans.” Such racializing tactics, which they call model minority logics,

weaponize an abstract version of one group to further racialize all minoritized groups

and regiment ethnoracial hierarchies. We identify three functions of model minori-

ty logics that perpetuate white supremacy in the academy, using linguistics as a case

study and underscoring the ways in which the discipline is already mired in racializing

logics that differentiate scholars of color based on reified hierarchies.

27

The authors consider the often-overlooked linguistic experiences of Asian

Americans in linguistics and show how “ideological positioning of Asian Amer-

icans as “honorary whites” is based on selective and heavily skewed images of

Asian American economic and educational achievements that circulate across in-

stitutional and dominant media channels.”

28

In “Inventing ‘the White Voice’: Racial Capitalism, Raciolinguistics & Cultur-

ally Sustaining Pedagogies,” H. Samy Alim explores

how paradigms like raciolinguistics and culturally sustaining pedagogies, among oth-

ers, can offer substantive breaks from mainstream thought and provide us with new,

just, and equitable ways of living together in the world. I begin with a deep engagement

with Boots Riley and his critically acclaimed, anticapitalist, absurdist comedy Sorry

to Bother You in hopes of demonstrating how artists, activists, creatives, and scholars

might: 1) cotheorize the complex relationships between language and racial capitalism

and 2) think through the political, economic, and pedagogical implications of this new

theorizing for Communities of Color.

29

Alim digs deep into models of aspirational whiteness in Sorry to Bother You and

shows how it goes past the mark. In the script, Boots states, “It’s not really a white

voice. It’s what they wish they sounded like. So, it’s like, what they think they’re

supposed to sound like.” All of the authors in this section examine varied kinds of

intervention strategies and programs in institutional education and social action

that can raise awareness of and help to ameliorate linguistic subordination and

sociolinguistic inequality in American society.

From our perspective, it is not sufficient to raise awareness and describe lin-

guistic inequality without attempting to confront and ameliorate that inequality.

Thus, our third and final set of papers by John Baugh, Sharese King and John R.

Rickford, and Norma Mendoza-Denton offer legal and policy alternatives that

152 (3) Summer 2023 13

Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley & Guadalupe Valdés

implement activities and programs that directly confront issues of institutional

inequality. As linguist Jan Blommaert puts it, “we need an activist attitude, one in

which the battle for power-through-knowledge is engaged, in which knowledge is

activated as a key instrument for the liberation of people, and as a central tool un-

derpinning any effort to arrive at a more just and equitable society.”

30

Our authors

illustrate the communicative processes involved when we use our human capacity

for language to work toward justice.

In “Linguistic Profiling across International Geopolitical Landscapes,” Baugh

“explore[s] various forms of linguistic profiling throughout the world, culminat-

ing with observations intended to promote linguistic human rights and the aspi-

rational goal of equality among people who do not share common sociolinguistic

backgrounds.”

31

Baugh extends his previous work on linguistic profiling into the

international geopolitical landscape and notes, in countries that have them, the

role that language academies play in reinforcing narrow norms, showing how those

practices relate to practices in countries where these processes are more organic

and situated in the educational systems.

In “Language on Trial,” King and Rickford draw on their case study of the testi-

mony of Rachel Jeantel, a close friend of Trayvon Martin, in the 2013 trial of George

Zimmerman v. The State of Florida.

32

They show that despite being an ear-witness (by

cell phone) to all but the final minutes of Zimmerman’s interaction with Trayvon,

and despite testifying for nearly six hours about it, her testimony was dismissed

in jury deliberations. “Through a linguistic analysis of Jeantel’s speech, comments

from a juror, and a broader contextualization of stigmatized speech forms and

linguistic styles,” they show that “lack of acknowledgment of dialectal variation

has harmful social and legal consequences for speakers of stigmatized dialects.”

33

Their work complements legal scholar D. James Greiner’s essay on empiricism in

law, from a previous volume of Dædalus, to show how empirical linguistic analysis

should be included in such models.

34

As King and Rickford state:

Alongside the vitriol from the general public, evidence from jury members suggested

that not only was Jeantel’s speech misunderstood, but it was ultimately disregarded in

more than sixteen hours of deliberation. With no access to the court transcript, unless

when requesting a specific playback, jurors did not have the materials to reread speech

that might have been unfamiliar to most if they were not exposed to or did not speak

the dialect.

35

In “Currents of Innuendo Converge on an American Path to Political Hate,”

Norma Mendoza-Denton shows that politicians’ “innuendo such as enthymemes,

sarcasm, and dog whistles” gave us “an early warning about the type of relation-

ship that has now obtained between Christianity and politics, and specifically

the rise of Christian Nationalism as facilitated by President Donald Trump.” She

demonstrates that “two currents of indirectness in American politics, one reli-

14 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language & Social Justice in the United States: An Introduction

gious and the other racial, have converged like tributaries leading to a larger body

of water.”

36

Anne H. Charity Hudley concludes the collection with “Liberatory Linguis-

tics,” offering the model as “a productive, unifying framework for the scholarship

that will advance strategies for attaining linguistic justice [. . .] [e]merging from

the synthesis of various lived experiences, academic traditions, and methodolog-

ical approaches.” She highlights promising strategies from her work with Black

undergraduates, graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, and faculty members

as they endeavor to embed a justice framework throughout the study of language

broadly conceived that can “improve current approaches to engaging with struc-

tural realities that impede linguistic justice.”

37

Charity Hudley ends by noting

how this set of essays is in conversation with the 2022 Annual Review of Applied Lin-

guistics on social justice in applied linguistics, and the forthcoming Oxford vol-

umes Decolonizing Linguistics and Inclusion in Linguistics, which “set frameworks for

the professional growth of those who study language and create direct roadmaps

for scholars to establish innovative agendas for integrating their teaching and re-

search and outreach in ways that will transform linguistic theory and practice for

years to come.”

38

As our summaries suggest, this collection of essays is diverse and comprehen-

sive, representing a range of situations and conditions calling for justice in lan-

guage. We hope these essays, along with other publications on this topic, broad-

en the conversations across higher education on language and justice. We are

extremely grateful to the authors who have shared their knowledge, research, ad-

vocacy, and perspectives in such lucid, accessible presentations.

about the authors

Walt Wolfram, a Fellow of the American Academy since 2019, is one of the pio-

neers of sociolinguistics. He is the William C. Friday Distinguished University Pro-

fessor at North Carolina State University, where he also directs the Language and

Life Project. He has published more than twenty books and three hundred articles

on language variation, and has served as executive producer of fifteen television

documentaries, winning several Emmys. His recent publications include Fine in the

World: Lumbee Language in Time and Place (with Clare Dannenberg, Stanley Knick, and

Linda Oxendine, 2021) and African American Language: Language Development from In-

fancy to Adulthood (with Mary Kohn, Charlie Farrington, Jennifer Renn, and Janneke

Van Hofwegen, 2021).

152 (3) Summer 2023 15

Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley & Guadalupe Valdés

Anne H. Charity Hudley is Associate Dean of Educational Affairs and the Bonnie

Katz Tenenbaum Professor of Education and African and African- American Stud-

ies and Linguistics, by courtesy, at the Graduate School of Education at Stanford

University. She is the author of four books: The Indispensable Guide to Undergraduate

Research (with Cheryl L. Dickter and Hannah A. Franz, 2017), We Do Language: English

Language Variation in the Secondary English Classroom (with Christine Mallinson, 2013),

Understanding English Language Variation in U.S. Schools (with Christine Mallinson,

James A. Banks, Walt Wolfram, and William Labov, 2010), and Talking College: Mak-

ing Space for Black Linguistic Practices in Higher Education (with Christine Mallinson and

Mary Bucholtz, 2022). She is a Fellow of the Linguistic Society of America and the

American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Guadalupe Valdés, a Fellow of the American Academy since 2020, is the Bonnie

Katz Tenenbaum Professor of Education, Emerita, in the Graduate School of Edu-

cation at Stanford University. She is also the Founder and Executive Director of the

English coaching organization English Together. Her books Con Respeto: Bridging the

Distances Between Culturally Diverse Families and Schools: An Ethnographic Portrait (1996)

and Learning and Not Learning English: Latino Students in American Schools (2001) have

been used in teacher preparation programs for many years. She has recently pub-

lished in such journals as Journal of Language, Identity, and Education; Bilingual Research

Journal; and Language and Education.

endnotes

1

See, for example, the statement by the Linguistic Society of America, “LSA Statement on

Race,” May 2019, https://www.linguisticsociety.org/content/lsa-statement-race.

2

Rosina Lippi-Green, English with an Accent: Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United

States (New York: Routledge, 2012).

3

R. L. G., “The Last Acceptable Prejudice,” The Economist, January 29, 2015, https://www

.economist.com/prospero/2015/01/29/the-last-acceptable-prejudice.

4

Cecilia Menjívar, “The Racialization of ‘Illegality,’” Dædalus 150 (2) (Spring 2021): 91–105,

https://www.amacad.org/publication/racialization-illegality; Jessica F. Green, “Less

Talk, More Walk: Why Climate Change Demands Activism in the Academy,” Dæda-

lus 149 (4) (Fall 2020): 151–162, https://www.amacad.org/publication/climate-change

-demands-activism-academy; D. James Greiner, “The New Legal Empiricism & Its Ap-

plication to Access-to-Justice Inquiries,” Dædalus 148 (1) (Winter 2019): 64–74, https://

www.amacad.org/publication/new-legal-empiricism-its-application-access-justice

-inquiries; Irene Bloemraad, Will Kymlicka, Michèle Lamont, and Leanne S. Son Hing,

“Membership without Social Citizenship? Deservingness & Redistribution as Grounds

for Equality,” Dædalus 148 (3) (Summer 2019): 73–104, https://www.amacad.org/

publication/membership-without-social-citizenship-deservingness-redistribution

-grounds-equality; and Sandy Baum and Michael McPherson, “The Human Factor: The

Promise & Limits of Online Education,” Dædalus 148 (4) (Fall 2019): 235–254, https://

www.amacad.org/publication/human-factor-promise-limits-online-education.

5

Norman Fairclough, Language and Power, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2001).

16 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language & Social Justice in the United States: An Introduction

6

Stephany Brett Dunstan, Walt Wolfram, Andrey J. Jaeger, and Rebecca E. Crandall, “Ed-

ucating the Educated: Language Diversity in the University Backyard,” American Speech

90 (2) (2015): 266–280, https://doi.org/10.1215/00031283-3130368.

7

Anne Curzan, Robin M. Queen, Kristin VanEyk, and Rachel Elizabeth Weissler, “Language

Standardization & Linguistic Subordination,” Dædalus 152 (3) (Summer 2023): 31, https://

www.amacad.org/publication/language-standardization-linguistic-subordination.

8

Kendra Nicole Calhoun, “Competing Discourses of Diversity and Inclusion: Institutional

Rhetoric and Graduate Student Narratives at Two Minority Serving Institutions” (PhD

diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 2021), https://www.proquest.com/open

view/552b09ea236453a210e8b541d03188fe/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

9

Walt Wolfram, “Addressing Linguistic Inequality in Higher Education: A Proactive

Model,” Dædalus 152 (3) (Summer 2023): 37, https://www.amacad.org/publication/

addressing-linguistic-inequality-higher-education-proactive-model.

10

William Labov, A Study of Non-Standard English (Washington, D.C.: Center for Applied

Linguistics, 1969), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED024053.pdf; Wesley Y. Leon-

ard, “Refusing ‘Endangered Languages’ Narratives,” Dædalus 152 (3) (Summer 2023):

https://www.amacad.org/publication/refusing-endangered-languages-narratives;

Guadalupe Valdés, “Social Justice Challenges of ‘Teaching’ Languages,” Dædalus 152

(3) (Summer 2023): https://www.amacad.org/publication/social-justice-challenges

-teaching-languages; and Julia C. Fine, Jessica Love-Nichols, and Bernard C. Perley,

“Climate & Language: An Entangled Crisis,” Dædalus 152 (3) (Summer 2023): 84–98,

https://www.amacad.org/publication/climate-language-entangled-crisis.

11

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, America’s Languages: Investing in Language Education

for the 21st Century (Cambridge, Mass.: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2017),

https://www.amacad.org/publication/americas-languages.

12

Paul Simon, The Tongue-Tied American: Confronting the Foreign Language Crisis (New York:

The Crossroad Publishing Company, 1980), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED206188.

13

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, America’s Languages, vii.

14

Ibid., 4.

15

Ibid., 6.

16

Valdés, “Social Justice Challenges of ‘Teaching’ Languages,” 53.

17

Ibid.

18

Leonard, “Refusing ‘Endangered Languages’ Narratives,” 69.

19

Ibid.

20

Fine, Love-Nichols, and Perley, “Climate & Language,” 84.

21

Ibid.

22

Dwight Bolinger, Language: The Loaded Weapon—The Use and Abuse of Language Today (New

York: Routledge, 2021).

23

Curzan et al., “Language Standardization & Linguistic Subordination”; Jonathan Rosa

and Nelson Flores, “Rethinking Language Barriers & Social Justice from a Raciolin-

guistic Perspective,” Dædalus 152 (3) (Summer 2023): 99–114, https://www.amacad

.org/publication/rethinking-language-barriers-social-justice-raciolinguistic-perspective;

and H. Samy Alim, “Inventing ‘The White Voice’: Racial Capitalism, Raciolinguistics

152 (3) Summer 2023 17

Walt Wolfram, Anne H. Charity Hudley & Guadalupe Valdés

& Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies,” Dædalus 152 (3) (Summer 2023): 147–166, https://

www.amacad.org/publication/inventing-white-voice-racial-capitalism-raciolinguistics

-culturally-sustaining.

24

Rosa and Flores, “Rethinking Language Barriers & Social Justice from a Raciolinguistic

Perspective,” 99.

25

Ibid., 101–102.

26

Aris Moreno Clemons and Jessica A. Grieser, “Black Womanhood: Raciolinguistic Inter-

sections of Gender, Sexuality & Social Status in the Aftermaths of Colonization,” Dædalus

152 (3) (Summer 2023): 115, 117, 119, 124, https://www.amacad.org/publication/black

-womanhood-raciolinguistic-intersections-gender-sexuality-social-status-aftermaths.

27

Joyhanna Yoo, Cheryl Lee, Andrew Cheng, and Anusha Ànand, “Asian American Racial-

ization & Model Minority Logics in Linguistics,” Dædalus 152 (3) (Summer 2023): 130,

https://www.amacad.org/publication/asian-american-racialization-and-model-minority

-logics-linguistics.

28

Ibid., 134.

29

Alim, “Inventing ‘The White Voice,’” 147.

30

Jan Blommaert, “Looking Back, What Was Important?” Ctrl+Alt+Dem, April 20, 2020,

https://alternative-democracy-research.org/2020/04/20/what-was-important.

31

John Baugh “Linguistic Profiling across International Geopolitical Landscapes,” Dædalus

152 (3) (Summer 2023): 167, https://www.amacad.org/publication/linguistic-profiling

-across-international-geopolitical-landscapes.

32

John R. Rickford and Sharese King, “Language and Linguistics on Trial: Hearing Rachel

Jeantel (and Other Vernacular Speakers) in the Courtroom and Beyond,” Language 92

(4) (2016): 948–988, https://www.linguisticsociety.org/sites/default/files/Rickford

_92_4.pdf.

33

Sharese King and John R. Rickford, “Language on Trial,” Dædalus 152 (3) (Summer 2023):

178, https://www.amacad.org/publication/language-on-trial.

34

Greiner, “The New Legal Empiricism & Its Application to Access-to-Justice Inquiries.”

35

King and Rickford, “Language on Trial,” 181.

36

Norma Mendoza-Denton, “Currents of Innuendo Converge on an American Path to Polit-

ical Hate,” Dædalus 152 (3) (Summer 2023): 194, https://www.amacad.org/publication/

currents-innuendo-converge-american-path-political-hate.

37

Anne H. Charity Hudley, “Liberatory Linguistics,” Dædalus 152 (3) (Summer 2023): 212,

https://www.amacad.org/publication/liberatory-linguistics.

38

Alison Mackey, Erin Fell, Felipe de Jesus, et al., “Social Justice in Applied Linguistics:

Making Space for New Approaches and New Voices,” Annual Review of Applied Linguis-

tics 42 (2022): 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190522000071; Anne H. Charity

Hudley and Nelson Flores, “Social Justice in Applied Linguistics: Not a Conclusion,

but a Way Forward,” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 42 (2022): 144–154, https://doi

.org/10.1017/S0267190522000083; Anne H. Charity Hudley, Christine Mallinson, and

Mary Bucholtz, eds., Decolonizing Linguistics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forth-

coming); and Anne H. Charity Hudley, Christine Mallinson, and Mary Bucholtz, eds.,

Inclusion in Linguistics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

18

© 2023 by Anne Curzan, Robin M. Queen, Kristin VanEyk &

Rachel Elizabeth Weissler

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license

https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_02015

Language Standardization &

Linguistic Subordination

Anne Curzan, Robin M. Queen, Kristin VanEyk &

Rachel Elizabeth Weissler

Language standardization involves minimizing variation, especially in written

forms of language. That process includes judgments about people who don’t or can’t

use the standard forms. These kinds of judgments can unfairly limit people’s access

to opportunities, including in educational and professional realms. In this essay, we

discuss standardized language varieties and the specific ways beliefs and ideologies

about them allow judgments about language to become judgments about people,

especially groups of people who share, or are presumed to share, gender, race, eth-

nicity, social status, education status, and numerous other socially salient identities.

After describing how the process of standardization occurs, we illustrate how the

expression of language peeves becomes embodied. Finally, we discuss how ideolo-

gies about standardized language circulate in higher education to the detriment of

many students, and include a range of suggestions and examples for how to center

linguistic justice and equity within higher education.

L

anguage peeves seem harmless, which only enhances their power. How

serious could it be to complain about people’s use of apostrophes or dou-

ble negatives or the contraction ain’t? The features under fire are relatively

trivial when it comes to mutual comprehension. At the same time, many articu-

lations of language peeves, intentionally or unintentionally, belittle or humiliate

those who have “transgressed,” which is not trivial. Such peeves can become a ref-

erendum on the people themselves rather than “just” their language. For example,

someone who uses ain’t may be understood as uneducated; or an expression like

we don’t want none of that is presumed to be illogical and thus a sign of a speaker’s

inability to think precisely. And these kinds of judgments can unfairly limit peo-

ple’s access to opportunities, including in educational and professional realms.

To understand the unfairness of these judgments and their real-world impli-

cations, it helps to return to our use of scare quotes around “just” in the previous

paragraph. The languages we speak are essential parts of our identities; they are

not just how we talk about the world but are part of who we are and part of our

152 (3) Summer 2023 19

Anne Curzan, Robin M. Queen, Kristin VanEyk & Rachel Elizabeth Weissler

cultures and communities. Further, the languages we speak are part of how we un-

derstand the world we live in. For example, one of the authors of this essay, who

is from the Southern United States, can use multiple modal verbs to indicate fin-

er distinctions in grammatical mood than are available with a single modal verb.

In the sentence “We might should go to the beach today,” the speaker indicates

both that it is an action that probably needs to be done and an action that may or

may not be feasible. This construction, acquired by speakers in toddlerhood, cre-

ates a different flavor for modal verbs and is tied to how a speaker shows polite-

ness. Multiple modals are nuanced and helpful. They are also often framed, both

by those who don’t use them and by some who do, as highly “incorrect” and as

signaling a lack of education and intelligence.

Given the connection of language to identity, culture, and community, judg-

ments about individuals’ language use are frequently linked to groups of people

(rather than specific individuals), particularly those connected by race, ethnicity,

gender identity, social status, geographic location, and education. At their most

troubling, overt judgments about language and imagined “correct” ways of speak-

ing reinforce social hierarchies and deny the richness of linguistic diversity. The

language gatekeeping that happens routinely in institutions of higher education

and elsewhere ultimately promotes the ideologies of the powerful and disempow-

ers those who are disenfranchised based on the various social groups of which

they are a part.

Language gatekeeping happens in both formal and informal ways in higher

education. For example, all four authors of this essay know colleagues who have

policies in their courses that penalize students if their written work contains, say,

more than three “errors” per page. Other colleagues give their students a list of

their language peeves (for example, using different than rather than different from, or

ending a sentence with a preposition, or using anyways rather than anyway, or using

multiple modals such as might could) that students should not use in their written

work if they want to please their instructor and receive a better grade. At a less for-

mal level, students themselves may “correct” their peers for saying something like

“aks” in “aks a question.” While not a formal correction tied to a grade, this judg-

ment and gatekeeping take multiple forms, from an explicit correction to derisive

laughter or eye-rolling. Similarly, we have all heard other instructors complain-

ing to a colleague that their students “can’t write” because they confused the ho-

mophones their and there or sent in their “collage application essay.” We’ll return

to the different kinds of language that are being corrected in these examples–

and the harmful language ideologies that justify this powerful gatekeeping.

These instructors and students are participating in a gatekeeping discourse

that circulates broadly in institutions beyond education, including popular me-

dia. Consider, for example, a 2021 feature in Reader’s Digest titled “11 Grammar

Mistakes Editors Hate the Most,” which offers a collection of grammatical peeves

20 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language Standardization & Linguistic Subordination

sourced from language experts like editors and college instructors.

1

The “mis-

takes” by “offenders” range from confusion of homophones (their/they’re/there)

to nonstandard apostrophes to the use of I for me. One editor-in-chief, irritated

by the abundance of grammatical errors on public signs, used her own pen to

correct them. She explains, “I’ve only done it once or twice, but when a mistake

makes my skin crawl, I have no shame.”

The use of phrases like “makes my skin crawl” is an example of language em-

bodiment, which in this case describes a physical response to a visual grammatical

“error.” It reflects how beliefs about language correctness are deeply held and how

they are both cognitively and physically naturalized–to the point where people

articulate that perceived mistakes cause physical pain (for example, ears or eyes

hurting, feeling ill). Figure 1 illustrates such embodiment.

Throughout this essay, we provide further examples of embodiment/embodied

responses that occur in the name of language standardization to illustrate how

deeply ingrained beliefs about what is and isn’t “correct” are.

Discussing language standardization is critical, given how deeply ideologies

about language use and correctness are embedded in our social interactions with

one another and in our cognitive capacities to both produce and interpret lan-

guage. Standardization often hides the fact that all varieties of all human languages

are equally capable of being “grammatical” in the sense that users have strong un-

derstandings of the rules that govern the variety. For this reason, we don’t use the

term dialect or accent to refer to less standardized varieties. Instead, we use variety.

2

In doing so, we are committing to the position that standardized varieties are not

better or worse than less standardized varieties. Yet the discourses that position

standardized varieties as better, correct, or the “real” language naturalize the as-

sumed superiority of the standardized variety. We must take seriously the power

of this naturalized discourse about language “correctness” because it facilitates

and often overtly promotes discrimination, both deliberate and unintentional.

We urge readers to consider the implications of language standardization

within their own fields. Language standardization supports one of the most con-

sistent forms of gatekeeping, and one in which every field represented in the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences participates. The ideological power of

language standardization holds true for English and for other languages, includ-

ing many found in the United States. For instance, there is a general prestige as-

sociated with the standardized form of Spanish used in Spain that relegates oth-

er forms of Spanish, such as Cuban or Mexican Spanish, to a significantly lower

status.

3

This version of an ideology about standardized language facilitates dis-

crimination against those who use varieties of Spanish other than those found in

Spain–and, of course, the same discrimination against minoritized varieties hap-

pens in Spain itself. When we unquestioningly reinforce the belief that the stan-

dardized variety is inherently “correct,” we almost always marginalize those who

152 (3) Summer 2023 21

Anne Curzan, Robin M. Queen, Kristin VanEyk & Rachel Elizabeth Weissler

are minoritized in ways that appear neutral but are in fact classist, racist, sexist,

and in other ways discriminatory.

4

H

igher education in the United States (and many places with a long histo-

ry of standardization) presupposes a standardized, edited written form

of English as the model for what is “correct” linguistically. We often talk

about this variety, “Standard English” (or even just “English”), as a stable, neu-

tral, locatable entity. Let us be clear: It is none of those things. In fact, the very act

of trying to defi ne Standard English reveals how slippery this notion is. For this

reason, it can be useful to start a discussion of Standard English with the process

of standardization, rather than the variety itself.

Standard languages do not magically or neutrally appear; they result from the

process of language standardization. The central goal of standardizing a language

Source: RD.com, Getty Images, https://www.rdasia.com/true-stories-lifestyle/humour/

23-grammar-memes-thatll-crack-you-up?pages=2 (accessed May 30, 2022).

Figure 1

Standard Grammatical Use of the Contraction “You’re”

22 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language Standardization & Linguistic Subordination

is to minimize variation in the selected variety, which can then be used to facili-

tate communication across regional and social dialects of a language. A common

by-product is shoring up social hierarchies based on who has access to the stan-

dardized variety, which comes to represent not only a shared standard but also

the one “correct” or “proper” way to use the language. Variation is natural to any

living language, so the process of standardization must always work against the

natural tendency for a language to morph over time, space, and social identities.

The process of language standardization is often described in four stages, first

outlined by sociolinguist Einar Haugen, which we’ve summarized below:

• Selection: A dialect of the language is chosen as the variety that will be

shared more broadly. Typically, this variety carries social, political, and/or

economic prestige based on the status of its speakers.

• Elaboration: As a more local variety is asked to take on a wider array of func-

tions (for example, legal documents and scientific writing), its available

resources–such as vocabulary and written style–must expand to meet the

varied needs of speakers and writers.

• Codification: As the variety comes to be more broadly shared, it starts to

become more regulated in an attempt to minimize variation across speak-

ers and writers.

• Acceptance: The variety is institutionalized as a standard in education, me-

dia, administrative functions, and elsewhere, and mastery of it becomes a

qualification for higher education and many professional careers.

5

Sociolinguists James Milroy and Lesley Milroy, who describe standardization as

an ideology in addition to a process, expand this model to include more stages:

selection, acceptance, diffusion, elaboration, maintenance, codification, and pre-

scription.

6

In these late stages (which are not necessarily linear), the standardized

variety often acquires prestige.

There is nothing formalized about these stages; no one “decides” to select a

variety and elaborate on it. Rather, selection often follows from the institution-

alized social power of particular users, and the stages follow the idea, promoted

within powerful social, cultural, and legal institutions, that standardized varieties

are inherently better than varieties that are less standardized. The standardized

variety is then available to confer social prestige on those who use it while the less

standardized varieties are seen as evidence of lower social prestige. For example,

in the United States, a roughly Midwestern variety of spoken English was “select-

ed” by broadcasters in the early to mid-twentieth century because it was neither a

Southern nor a Northeastern variety of American English.

7

One of the important

aspects of this selection can be seen in films from the early through the late 1950s,

in which varieties associated with the Northeast become less and less prestigious.

152 (3) Summer 2023 23

Anne Curzan, Robin M. Queen, Kristin VanEyk & Rachel Elizabeth Weissler

In the film Philadelphia Story (1940), Katherine Hepburn’s character Tracy Lord

uses language associated with the Northeast to mark her upper-class status. By

1954, however, Marlon Brando’s Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront uses language

associated with the Northeast (specifically New York) to mark lower-class status.

The selection of the “standard” variety is not neutral, nor are the parties re-

sponsible for its codification, maintenance, and prescription. In some countries,

there is an identifiable institution that promotes standardization, such as the

Académie Française in France. In the United States, by contrast, standardization

is enforced by a loose network of language authorities, including editors, teach-

ers, dictionary and usage guide writers, language pundits, and the like. In English,

codification and prescription took hold in Britain and the United States and be-

yond in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with the proliferation of dictio-

naries and then style guides that would become standard reference tools in the

educational system.

Standardization works to limit change and variability within a language vari-

ety. Change still happens in standardized varieties (for example, the introduction

of the passive progressive–the house is being built–in the nineteenth century), but

it is often resisted and only slowly accepted (for example, the use of “they” as a

singular pronoun, which occurs as early as the fourteenth century).

8

Therefore,

we use the phrase Standardized American English to capture the dynamic processes

at work in this variety. Standardized American English (henceforth referred to in

this essay as SAE) is easier to distinguish in writing than in speech. While we can

identify some features that are prototypically standard (for example, single nega-

tion, use of third-person singular -s in the present tense as in she thinks, he dreams),

SAE is often identified by what it isn’t (for example, fixin to, ain’t, multiple modals,

merger of the vowel in pen and pin [but the merger of the vowel in cot and caught

is not stigmatized as nonstandard], aks rather than ask).

9

As these few examples

capture, these distinctions between standardized and nonstandardized language

features are often raced and classed.

While SAE is often described as neutral or unmarked, it is neither. It may not

have distinctive markers of geographical location, but SAE indexes whiteness and

higher socioeconomic class.

10

It is enforced and reinforced through discourses of

“correctness” in our educational system, editorial practices, a proliferation of us-

age guides and style manuals, and technologies such as grammar checkers built

into word processors.

It is important to note here that language gatekeeping and the discourse of cor-

rectness are not entirely consistent and apply to variety and register (or stylistic)

differences as well as spelling and punctuation. Let’s return to the examples in the

introductory section of common language gatekeeping practices in higher educa-

tion. Some of the examples involve nonstandard pronunciations or grammatical

features associated with social groups, such as aks, anyways, and multiple modals.

24 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language Standardization & Linguistic Subordination

Some of the examples are stylistic distinctions, in which arguably both variants

fall within standardized usage (for example, different from versus different than or

ending a sentence with a preposition). And especially with these kinds of pre-

scriptive rules, not all language authorities will agree on what counts as an error.

11

For example, not all readers of this essay will care equally, or at all, about different

than, or hopefully used to mean “it is hoped,” or the use of impact as a verb. The list

goes on. Then there are typos and “grammos” or homophonous grammar errors

(for example, their/they’re, its/it’s), which are entirely written phenomena–and in

some cases created by autocorrect functions found on mobile devices that, for in-

stance, often revert the possessive its to the contracted it’s, despite attempts by the

typers to change it.

12

At some fundamental level, when we think about language as

a communicative system, these grammos are trivial (we cannot even hear them in

speech) and most writers have made them when writing quickly or in less proofed

genres. Yet the stakes for making them can be socially and professionally high:

they can be seen as markers not just that a writer may not have proofed carefully

but also that a writer is lazy, unintelligent, unqualified.

The consequences of language standardization are significant because of the

beliefs the process creates and sustains. While, in theory, the standardized variety

could coexist with nonstandard varieties in a way that legitimizes and celebrates

the richness and systematicity of linguistic diversity, the commonsense belief that

the standardized variety is inherently better results in the degradation of other va-

rieties, including both regional and social varieties of the language that are core

cultural markers of communities. This ideological system, typically referred to as

Standard Language Ideology (SLI), can be summarized as “a bias toward an ab-

stract, idealized language, which is imposed and maintained by dominant institu-

tions and which has as its model the written language, but which is drawn primar-

ily from the spoken language of the upper middle class.”

13

As a result, SLI allows

those in power to exclude and restrict access to power for speakers of minoritized

varieties in many sectors of the public domain.

SLI generally works invisibly, by nature of its “commonsense” approach to

right and wrong (or better and worse) language patterns. It allows, if not encour-

ages, the dissemination of misinformation about language variation, and speak-

ers of all varieties tend to accept SLI without question. This ideology captures the

power of convincing speakers that their own language varieties, which they use

for diverse communicative purposes, are “wrong” if they do not correspond with

what is seen as standard. This bias applies not only to SAE but also to many lan-

guages in the United States such as Spanish, which is spoken variably by people

in the United States depending on their background and origin. Because the stan-

dard variety of a language functions as the uninterrogated norm, other varieties

are relegated to the margins as linguistically inferior, even if they may carry so-

cial capital. Those who speak nonstandardized or semistandardized dialects are

152 (3) Summer 2023 25

Anne Curzan, Robin M. Queen, Kristin VanEyk & Rachel Elizabeth Weissler

labeled ungrammatical, which translates to illogical and untrustworthy. Such dis-

information consolidates power, reifies it, and naturalizes its reification.

T

he embodiment of negative reactions to linguistic (primarily orthograph-

ic) “errors” presents a fascinating aspect of the language standardization

process, which can link bodily sensation to beliefs about standardized and

nonstandardized forms of language. Eyerolls, for instance, are a form of embod-

ied annoyance, as is saying someone’s grammar makes you sick (or [sic]), as seen

in Figure 2.

Though theories of embodiment have made their way across fields, from cog-

nitive neuroscience to robotics to anthropology to some areas of linguistics, they

have not been widely incorporated into theories of language standardization.

14

Nonetheless, embodiment offers fertile ground for understanding linguistic judg-

ment and prejudice. When a person expresses that grammatical errors “make

their skin crawl,” or when certain speech modalities such as creaky voice or up-

talk are described as an “embodied contagion” or metaphorical viral infection, we

see a direct link to specific ideologies about language that set up the standardized

form as correct, beautiful, healthy, and pure.

15

Further, these embodied physio-

logical responses to language variation suggest how deeply naturalized standard

language ideologies are, including among the most highly educated.

Language production and perception–spoken, written, or signed–always en-

gage the body directly: the hands, the mouth, the larynx, the lungs, the ears, the

eyes, the motor system, and the processing systems in the brain.

16

This materi-

al physicality is simultaneously involved in both producing and perceiving lan-

guage, including linguistic forms understood as being correct because they are

standardized. Most important, these responses embody the power of standard-

ization and the challenges involved in dislodging that power. Therefore, engaging

with and changing SLI, especially those that subordinate other people’s linguistic

production, requires confronting their embodiment.

17

One area of embodiment that occurs with some frequency when grammar

“errors” are under consideration is laughter. Laughter is a physical characteristic

of and reaction to a range of affective states, including playfulness, amusement,

joy, but also discomfort, dismissal, schadenfreude, or tease.

18

In the context of

language standardization, attempts to evoke laughter most typically involve teas-

ing, schadenfreude, and superiority, all of which are negatively valenced toward

the user of grammar “errors.”

The connection between public humor about grammar and a taunting or supe-

rior affect can be seen in the frequency with which the “humor” of many grammar

memes derives from metaphors of sickness and death, as seen in Figures 3 and 4.

In examples like Figures 3 and 4, in which the memes discuss pain and death as be-

ing brought on specifically by grammatical “errors,” it becomes clear how ideolo-

26 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language Standardization & Linguistic Subordination

Source: Logo of the public Facebook group “Bad Grammar Makes Me [Sic].”

Figure 2

Bad Grammar Makes Me [Sic]

Source: Taken from Lenia Crouch, “Grammar Memes to Make Your Day,” The EMS Sound,

February 6, 2018, https://emssound.net/1560/fun-and-games. Made using https://imgflip.com.

Figure 3

“When You Use Bad Grammer [sic] It Kills Me Again”

152 (3) Summer 2023 27

Anne Curzan, Robin M. Queen, Kristin VanEyk & Rachel Elizabeth Weissler

gies about the inherent correctness and superiority of the standard are reinforced

through the representation of embodied illness.

In surfacing these ideologies about a standardized language, memes and other

“humorous” displays of grammar errors are immediately available to denigrate

socially and linguistically marginalized groups of people. For instance, articles

such as Business Insider’s “The 13 Celebrities with the Worst Grammar on Twit-

ter” are meant to elicit a visceral and critical response.

19

Despite the availability

of many celebrities with “poor grammar” who embody a range of identities on

Twitter, eleven of the thirteen celebrities in this article are People of Color, includ-

ing Queen Latifah who is criticized for using “U” in place of “you” in a tweet, and

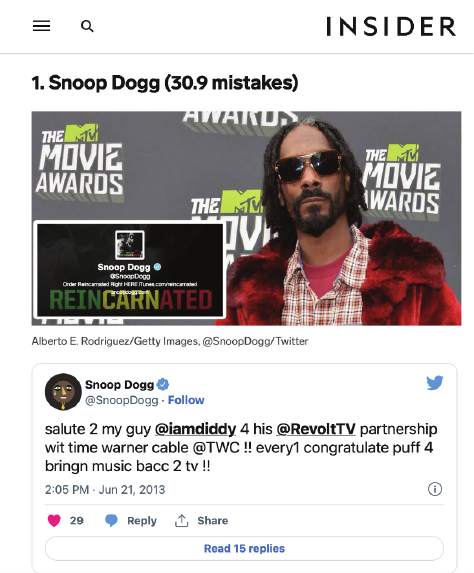

Snoop Dogg for using numbers “2” and “4” in lieu of “to” and “for” (see Figure 5).

These forms are clear (and at this point, largely standardized) ways to reduce

the number of characters in a tweet since Twitter limits how many characters a

single tweet may have. These celebrities are using the orthographic norms of the

medium; nonetheless, they are criticized for using especially poor grammar.

Many news organizations have features about poor grammar that are framed

in terms of the embodiment of grammar scorn, for instance, BuzzFeed’s article

“19 Grammar Fails That Will Make You Shake Your Head Then Laugh Out Loud,”

CNBC’s article “The 11 Extremely Common Grammar Mistakes That Make People

Figure 4

“My Eyes Are Burning”

Source: Taken from Rose Ledgard, “Grammar Memes,” Rose Ledgard: MA Major Project, Oc-

tober 10, 2012, https://roseledgarddesigns.wordpress.com/2012/10/10/grammar-memes.

Made using https://quickmeme.com.

28 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Language Standardization & Linguistic Subordination

Figure 5

Snoop Dogg Tweet Using Numbers “2” and “4” in Lieu of “To” and “For”

Source: Kirsten Acuna, “The 13 Celebrities with the Worst Grammar on Twitter,” Business In-