UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

1

The Coalition for

Physician Accountability’s

Undergraduate Medical

Education-Graduate

Medical Education

Review Committee (UGRC):

Recommendations for Comprehensive

Improvement of the UME-GME Transition

https://physicianaccountability.org/

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

2

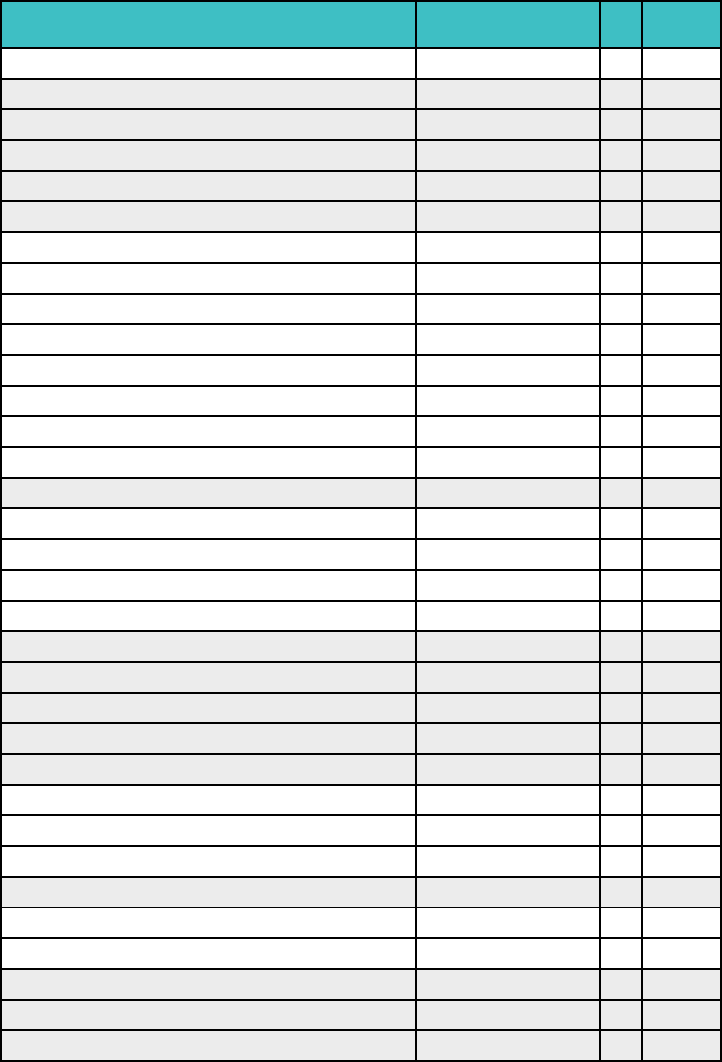

Table of ContentsTable of Contents

Competencies

and Assessments

FIVE RECOMMENDATIONS

Competencies

and Assessments

FIVE RECOMMENDATIONS

UGRC Members

Competencies

and Assessments

FIVE RECOMMENDATIONS

4

Competencies

and Assessments

FIVE RECOMMENDATIONS

Competencies

and Assessments

FIVE RECOMMENDATIONS

Competencies

and Assessments

FIVE RECOMMENDATIONS

Competencies

and Assessments

FIVE RECOMMENDATIONS

Competencies

and Assessments

FIVE RECOMMENDATIONS

Competencies

and Assessments

FIVE RECOMMENDATIONS

Acknowledgments

5

Final UGRC

Recommendations

and Themes

10-26

Executive Summary

6-9

UGRC Process

28-33

References

43

Limitations

42

Overview

3

Learner’s Journey

27

Future Ideal State

34-37

Impact of Public

Commentary

38

Appendix A:

Glossary of Terms

and Abbreviations

45-46

Appendix B:

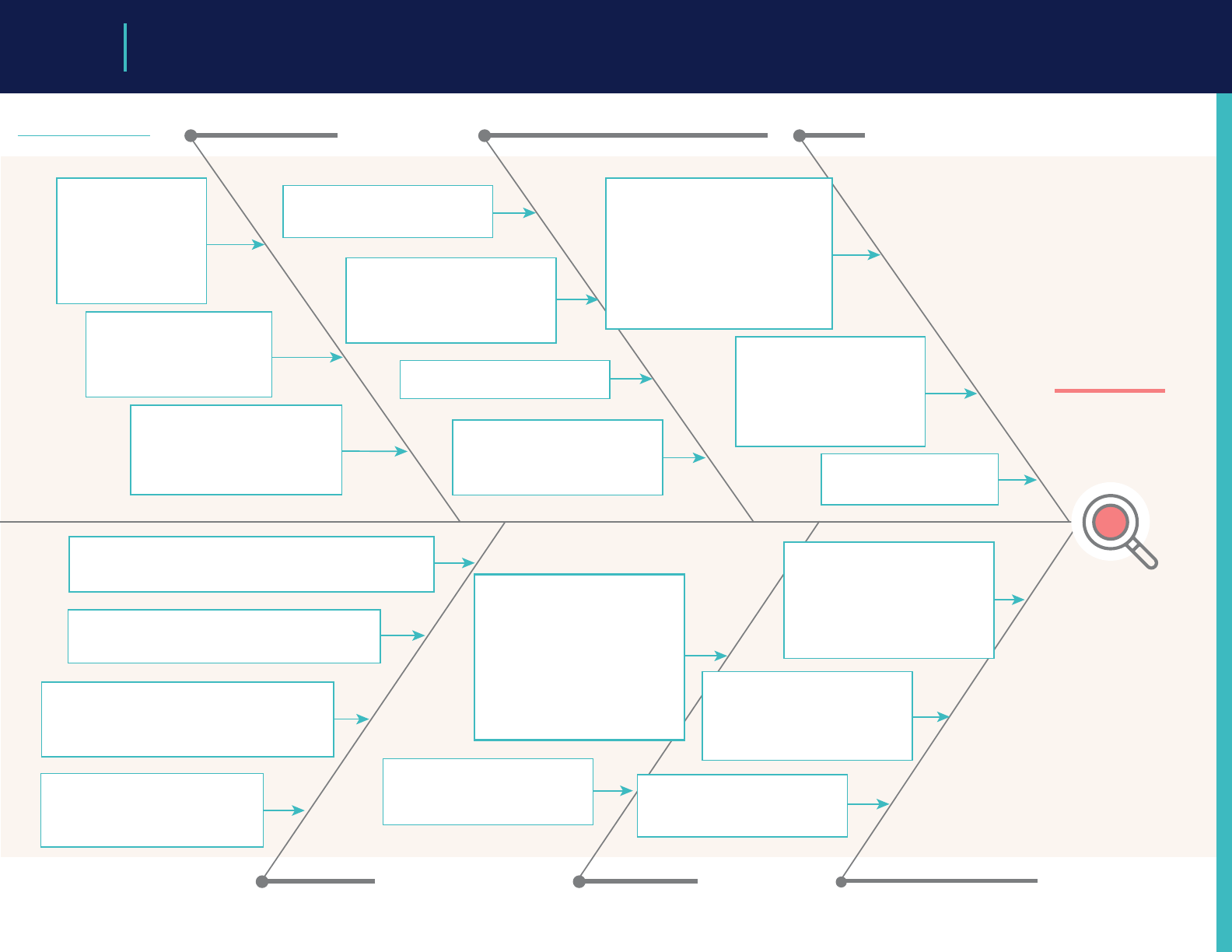

Workgroup Ishikawa Diagrams (Fishbones)

Created for Root Cause Analysis

47-50

Appendix C:

Final Recommendations

with Complete Templates

50-123

Appendix D:

Preliminary Recommendations

Released on April 26, 2021

125-138

Appendix E:

Analysis of the Public

Comments

139-275

Consolidation and

Sequencing

39-41

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

3

Overview

In 2020, the Coalition for Physician Accountability (Coalition) formed a new committee to examine the transition

from undergraduate medical education (UME) to graduate medical education (GME). The UME-GME Review

Committee (the “UGRC” or the “Committee”) was charged with the task of recommending solutions to identied

challenges in the transition. These challenges are well known, but the complex nature of the transition together

with the reality that no single entity has responsibility over the entire ecosystem has perpetuated the problems

and thwarted attempts at reform.

Using deliberate and thoughtful methods, the UGRC spent 10 months exploring, unpacking, discussing, and

debating all aspects of the UME-GME transition. The Committee envisioned a future ideal state, performed a root-

cause analysis of the identied challenges, repeatedly sought stakeholder input, explored the literature, sought

innovations being piloted across the country, and generated a preliminary set of potential solutions to the myriad

problems associated with the transition. Initial recommendations were widely released in April 2021, and feedback

was obtained from organizational members of the Coalition as well as interested stakeholders through a public

call for comment. This feedback was instrumental to rening, altering, and improving the recommendations into

their nal form. The UGRC also responded to feedback by consolidating similar recommendations, organizing

them into more cogent themes, and sequencing them to guide implementation.

The UGRC has presented a total of 34 nal recommendations, organized around nine themes, for comprehensive

improvement of the UME-GME transition. The Committee has formally handed o these recommendations to the

Coalition for their consideration and implementation. Importantly, the UGRC strove to abide by an agreed upon set

of guiding principles that gave primacy to the public good and that championed diversity, equity, and inclusion. The

Committee believes that the recommendations are interconnected and should be implemented as a complete

set. Doing so will create better organizational alignment, likely decrease student costs, reduce work, enhance

wellness, address inequities, better prepare new physicians, and enhance patient care.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

4

UGRC Members

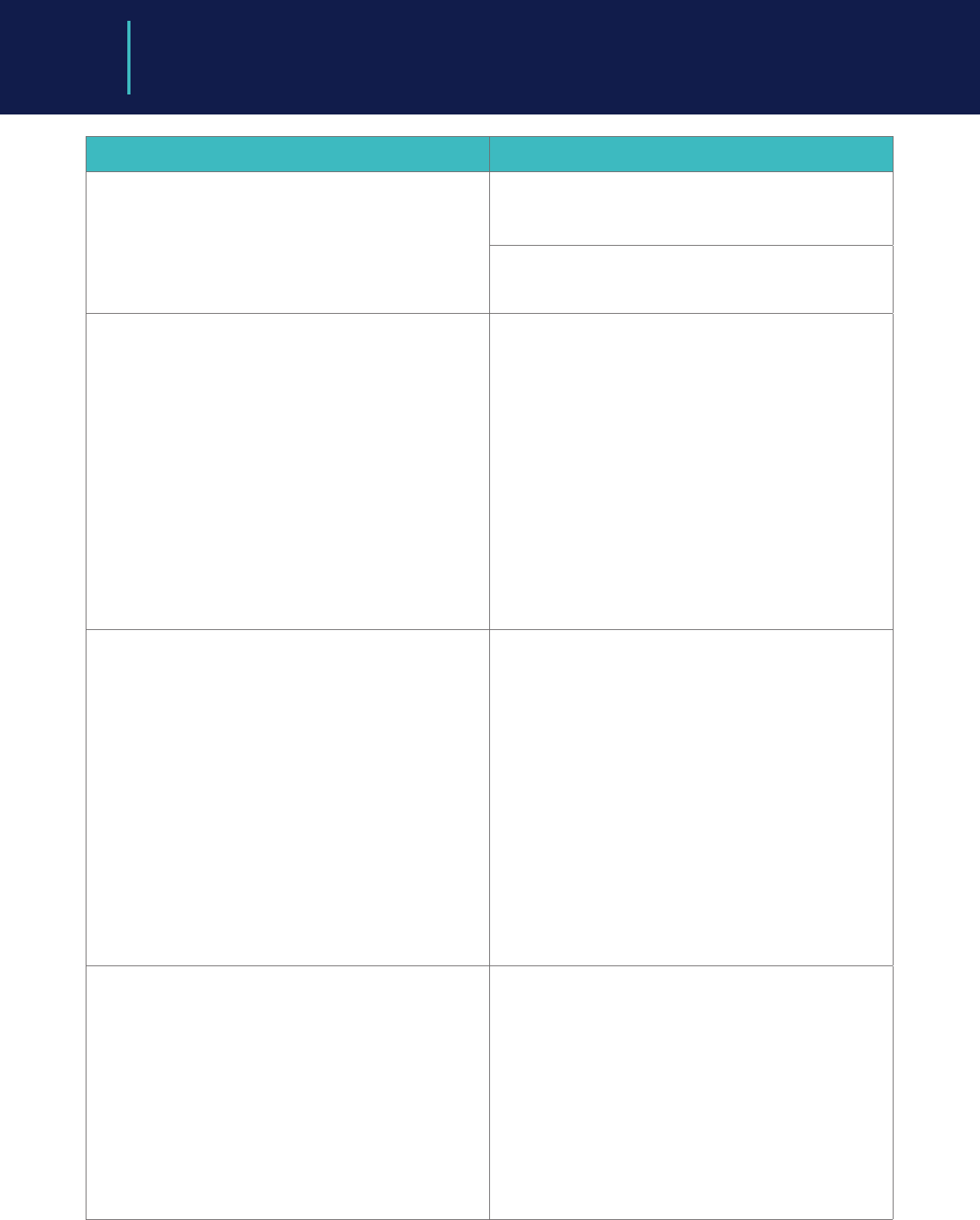

The members of the UME-GME Review Committee (UGRC), their pertinent constituency or organizational

aliation, and their workgroup assignments are listed in the table below. Please refer to the section of this report

on “UGRC Process” for details about each workgroup. A complete glossary of terms and constituency/organization

names can be found in Appendix A.

Name Constituency/Organization Workgroup Assign-ment

Richard Alweis DIO B

Steven Angus DIO A

Michael Barone NBME A

Jessica Bienstock DIO D and Bundling

Maura Biszewski AOA D

Craig Brater ECFMG A and Bundling

Jesse Burk Rafel Resident C

Andrea Ciccone Lead Coalition Sta Member Unassigned

Susan Enright (Workgroup B Leader) Medical Education B

Sylvia Guerra Student B and DEI

Daniel Giang (Bundling Workgroup Leader) DIO C and Bundling

John Gimpel NBOME B

Karen Hauer (Workgroup A Leader) Medical Education A

Carmen Hooker Odom Public Member B

Donna Lamb NRMP B

Grant Lin Resident D, DEI, and Bundling

Elise Lovell (UGRC co-chair) OPDA C

George Mejicano (UGRC co-chair) Medical Education D and DEI

Thomas Mohr AACOM C

Greg Ogrinc ABMS D and DEI

Juhee Patel Student A

Michelle Roett (DEI Workgroup Leader) Medical Education D and DEI

Dan Sepdham Residency Program Director C

Susan Skochelak AMA D

Julie Story Byerley (Workgroup D Leader) Medical Education D and Bundling

Jennifer Swails (Workgroup C Leader) Residency Program Director C and Bundling

Jacquelyn Turner Clerkship Director C and DEI

Alison Whelan AAMC B

Pamela Williams Medical Education A

William Wilson Public Member A

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

5

Acknowledgements

The UGRC would like to acknowledge the signicant contributions of the following individuals, whose eorts were

integral to the successful completion of the Committee’s charge.

We greatly appreciate the dedication and commitment demonstrated over the past year by the UGRC

workgroup leads: Julie Byerley, Susan Enright, Daniel Giang, Karen Hauer, Michelle Roett, and Jennifer Swails. Our

public members, Carmen Hooker Odom and Reverend William Wilson, consistently focused our work on our

ultimate responsibility, the public good.

Andrea Ciccone (NBME, AOA), served as primary Coalition sta support to the UGRC, and provided invaluable

insights, perspectives, and organization.

We sincerely thank our outstanding project manager Chris Hanley (AAMC) and communications director Joe

Knickrehm (FSMB). Research librarians Kris Alpi, Robin Champieux, and Andrew Hamilton (Oregon Health & Science

University) enthusiastically guided our evidence informed approach. A team consisting of Dana Kerr, Matthew

Roumaya, Carol Morrison, Ulana Dubas, and Lauren Foster (NBME) performed the important analysis of the public

commentary, while Susan Morris and Sheila FitzPatrick (ABMS) managed graphic design. Our medical writer

Victoria Stagg Elliott (AMA) contributed signicantly to the creation of this report.

The members of the Coalition Management Committee met throughout this process and oered relevant

guidance and context.

Finally, we are eternally grateful to each member of the UGRC, who contributed their time, passion, expertise, and

experience from across the arc of medical education, in the common cause of improving the UME-GME transition

for all involved, and improving the medical care provided in our society.

Elise Lovell, MD

George Mejicano, MD, MS

UGRC co-chairs

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

6

Executive Summary

In the summer of 2020, a Planning Committee of the Coalition for Physician

Accountability (Coalition) selected the members of a new committee – the

Undergraduate Medical Education (UME) to Graduate Medical Education

(GME) Review Committee (UGRC) – and charged them with the task of

recommending solutions to identied challenges in the UME-GME transition.

1

The UGRC is pleased to submit this report, which includes the 34 nal

recommendations for comprehensive improvement of the UME-GME

transition, to the Coalition for their consideration and implementation.

Introduction:

The charge to the UGRC stated that there are identied challenges in the transition between medical school and

residency that are negatively impacting the UME-GME transition.1 These challenges include, but are not limited to,

the following:

• Disproportionate attention towards nding and lling residency positions rather than on assuring learner

competence and readiness for residency training;

• Unacceptable levels of stress on learners and program directors throughout the entire process;

• Inattention to optimizing congruence between the goals of the applicants and the mission of the programs to

ensure the highest quality health care for patients and communities;

• Mistrust between medical school ocials and residency program personnel;

• Overreliance on licensure examination scores in the absence of valid, trustworthy measures of students’

competence and clinical abilities;

• Lack of transparency to students on how residency selection actually occurs;

• Increasing nancial costs to students as well as opportunity costs to programs associated with skyrocketing

application numbers;

• The presence of individual and systemic bias throughout the transition; and

• Inequities related to specic types of applicants such as international medical graduates.

In recent years, these and related challenges have expanded to the point that they are causing severe strain on

the entire system. Simply put, there is an emerging consensus and urgency to bring forth solutions and as stated

by the Planning Committee,1 that the “UME-GME community is energized at this moment to solve these problems,

and should therefore act boldly and fairly with transparency, while thoughtfully considering stakeholder input, and

utilizing data when available.”

1

In addition to understanding the challenges noted above, the UGRC had to develop a shared concept of what

comprises the “UME-GME transition.” Through its deliberations, the Committee came to a collective understanding

that the transition encompasses a complex ecosystem involving many individuals and organizations. The transition

begins during the preclinical phase of medical school as students consider specialty options, are counseled by

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

7

Executive Summary

mentors and faculty advisors, and embark on the long journey of professional identity formation. During their

clinical years, students participate in patient care in numerous settings and on dierent rotations, choose a

variety of electives, decide on a specialty, prepare application materials, research residency programs, apply to

many programs, are oered and partake in interviews, interact with program personnel, are selected through a

matching process, undergo hiring and credentialing, complete advanced skills training courses, experience major

life transitions, initiate new support structures, begin employment, participate in orientation, assume signicantly

more patient care responsibilities, and embed themselves within a learning and work environment that they will

call home for the next three to seven years. In other words, the UME-GME transition is not simply the application,

interview, and match process. Moreover, the transition does not end at the start of orientation to their rst year of

training. For unmatched students and international medical graduates, the process may take even longer.

As learners navigate through the UME-GME transition, they interact with numerous organizations with jurisdiction

over specic components of the process. Each organization plays a role and impacts the success of the

transition. However, the ecosystem is not governed by a single entity. In essence, it is a decentralized collection of

interdependent parts, each with their own interests, which currently do not communicate eectively or function

cohesively. Solutions that bring the components of the transition into better alignment could have many positive

outcomes and will likely decrease student costs, reduce work, enhance wellness, address inequities, better

prepare new physicians, and enhance patient care.

Background:

In 2018, a national conversation culminated regarding the use of numeric scores associated with medical licensing

examinations in residency applicant screening and selection. In response, the chief executive ocers of ve

national organizations (AMA, AAMC, ECFMG, FSMB, and NBME) agreed to co-sponsor an Invitational Conference on

USMLE Scoring (InCUS).

2

InCUS took place in March 2019 with a primary goal of reviewing the practice of numeric

score reporting. Three of the recommendations that emerged focused on the USMLE:

(a) Reduce the adverse impact of the overemphasis on USMLE performance in residency screening and

selection through consideration of changes such as pass/fail scoring;

(b) Accelerate research on the correlation of USMLE performance to measures of residency performance

and clinical practice; and

(c) Minimize racial demographic dierences in USMLE performance.

In contrast, the fourth InCUS recommendation focused on the UME-GME transition: Convene a cross-organizational

panel to create solutions for the assessment and transition challenges from UME to GME. The nal report from

InCUS noted that there was general agreement that changes in scoring of licensure examinations would not

address important aspects of the UME-GME transition system that needed attention. “It was acknowledged

that many organizations and stakeholder groups have responsibility for improving this transition. Yet if many are

responsible, a concern exists that no one group will take ownership or feel empowered to carry on the broader

conversation necessary to bring about appropriate change.”

2

In September 2019, a proposal was made to the Coalition to convene a UME-GME Review Committee in line

with the fourth recommendation from InCUS.

3

As a result, a Planning Committee was created by the Coalition

to develop the construct, membership, and charge of the Review Committee, which would be responsible for

recommending solutions to identied challenges in the UME-GME transition.

1

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

8

Executive Summary

The UGRC’s Guiding Principles

As stated above, the UGRC was charged with the task of recommending solutions to identied challenges in the

UME-GME transition. Although the Committee was encouraged to act boldly, thoughtfully consider stakeholder

input, and utilize data whenever possible, the UGRC’s primary goals were to ensure learner competence and

readiness for residency and to foster wellness in learners, sta, faculty members, and program directors.

1

In

addition, the UGRC was tasked to devote attention to the following items:

• Optimizing t between applicants and programs to ensure the highest quality health care for patients

and communities;

• Increasing trust between medical schools and residency programs;

• Mitigating current reliance on licensure examinations in the absence of valid, standardized, trustworthy

measures of students’ competence and clinical care;

• Increasing transparency for applicants to understand how residency selection operates;

• Considering the needs of all types of applicants in making its recommendations;

• Considering nancial cost to applicants throughout the application process; and

• Minimizing individual and systemic bias throughout the UME-GME transition process.

The UGRC melded these principles into a single tenet that was kept front of mind during its deliberations and

related work: above all else, the UME-GME transition must optimally serve the public good. Inherent to that tenet,

the Committee consistently focused on the importance of increasing diversity, enhancing equity, and championing

inclusion.

The Work of the UGRC

Seven consensus steps prepared the UGRC to successfully accomplish the task of generating recommendations:

• Elaborate the charge to include optimal preparation for residency by leveraging learners’ time and

experiences between the Match and the initial months of training.

• Require level setting to ensure that all UGRC members had common understanding of the UME-GME

transition.

• Use the concept of backward design to envision a future ideal state that helps create a system that

produces it.

• Produce Ishikawa diagrams (i.e., shbones) to determine the root causes that underly the many

challenges currently associated with the transition.

• Articulate the desired outcome and understand the root problems before generating solutions.

• Identify potential solutions and innovations described in the literature or implemented by institutions

across the country.

• Embrace a consensus approach to endorsing recommendations, informed by available evidence.

Generation and Adoption of Preliminary Recommendations

The UGRC did not begin the process of generating potential solutions to the identied problems of the transition

until the work described above was complete. Even then, the generation of the preliminary recommendations

was focused and deliberate to ensure that background material could be assembled, that each potential solution

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

9

Executive Summary

was thoughtfully considered, and that there was ample time and space to discuss contentious ideas. Each

recommendation was linked to the future ideal state as well as to root causes of problems with the transition.

In addition, the co-chairs decided to frame each recommendation in broad terms, to include specic

examples on how a recommendation might be implemented, and to list both pros and cons for each potential

recommendation. Successful implementation of the UGRC’s recommendations relies on the cooperation of

multiple entities since the challenges within the transition are interdependent and not under the control of any

one organization or stakeholder group. Recommendations based on principles and that describe characteristics

of what can be achieved are more likely to garner support compared to granular recommendations that might

be readily dismissed as unrealistic or politically dicult. In addition, recommendations with a high degree of

consensus will be harder to ignore than those adopted by the UGRC by a simple majority.

In April 2021, the UGRC adopted 42 preliminary recommendations organized around 12 themes. The preliminary

recommendations and pertinent background material were presented to the Coalition, followed one week later

by their widespread release and a call for public comment.

Response to Feedback and Next Steps

Feedback about the preliminary recommendations was obtained from the organizational members of the

Coalition as well as from stakeholders through a public, month-long call for comments. This feedback was shared

with each member of the UGRC so that input from the Coalition and external stakeholders could inform the

Committee’s nal recommendations. Feedback obtained by the UGRC co-chairs through dialogue with students,

program directors, DIOs, medical educators, medical school deans, and international medical graduates –

obtained through purposeful outreach to those groups – was considered before nalizing the recommendations.

In response to all feedback, the UGRC made important changes to its preliminary recommendations. The changes

included signicant editing, clarication, and renement of language; complete reworking of a recommendation

addressing application inflation; and judiciously combining similar ideas to reduce the overall number of

recommendations. Of note, 32 of the preliminary recommendations were impacted by the feedback obtained

through public commentary.

Further, the co-chairs created a “bundling workgroup” tasked to consolidate similar recommendations, to

sequence those that were interdependent with one another, and to re-organize them into more cogent themes.

As a result of these eorts, the UGRC has adopted 34 nal recommendations, organized around nine themes,

to comprehensively improve the UME-GME transition. Moreover, the recommendations within each theme are

sequenced in chronologic order to guide their implementation. A fully textualized and comprehensive narrative on

each recommendation can be found in Appendix C.

The Committee believes that each proposed change will produce positive results and that implementation of

the complete set of recommendations will improve the entire transition. The UGRC also recognizes that each

recommendation may be categorized as transactional, investigational, or transformational in nature. Though

certain recommendations are designed to garner “early wins” by reducing the signicant stress felt by students

and program directors, the UGRC believes that the transformational recommendations are of greatest

importance because they align the medical community with a shared interest to promote the public good.

With the delivery of the 34 nal recommendations and this accompanying report, the work of the UGRC is now

complete. The Coalition will meet in late summer 2021 to discuss the nal recommendations and consider next

steps towards implementation.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

10

Collaboration and Continuous

Quality Improvement

RECOMMENDATIONS

1

Convene a national ongoing committee to manage continuous quality improvement

of the entire process of the UME-GME transition, including an evaluation of the

intended and unintended impact of implemented recommendations.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

One of the challenges in creating alignment and making improvements is the lack of a single body with

broad perspective over the entire continuum. This creates a situation where organizations and institutions

are unnecessarily and counterproductively isolated, without a shared mental model or mission. A convened

committee, that includes learner and public representatives, should champion continuous improvement to the

UME-GME transition, with the focus on the public good.

THEME

2

In addition to supporting collaboration around the UME-GME transition, this national

committee should: develop and articulate consensus around the components of

a successful residency selection cycle; explore the growing number of unmatched

physicians in the context of a national physician shortage; and foster future research

to understand which factors are most likely to translate into physicians who fulll the

physician workforce needs of the public.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Currently, the medical education community lacks a shared mental model of what constitutes a successful

transition from UME to GME, and also what factors predict that success. The lack of agreement leads to conflict

over the content of applications as well as the resources required for a residency selection cycle. Success could

include simple educational outcomes such as completing training, board certication, or lack of remediation.

Alternatively, applicant-specic factors may be more important, such as likelihood of choosing the same

program again. Success may be dened solely on the public good, based on the ll rate of programs and

the number of physicians practicing in underserved areas. Or, it may be that successful residency selection is

institutionally specic based on its mission and community served, with some institutions focused on research

and others on rural communities. The committee should articulate the factors associated with a successful

residency selection cycle so they can be appropriately emphasized in the UME-GME transition, especially as

changes are made to the process.

The committee should report on data trends, implications, and recommended interventions to address the

growing number of unmatched physicians. This analysis should include demographic data to examine diversity,

specialty disparities in unmatched students, number of applications, grading systems, participation in SOAP,

post-SOAP unmatched candidates, match rate in subsequent years of re-entering the match pool, and attrition

rates of learners during residency. This recommendation is intended to urge UME programs and institutions

to utilize a continuous quality improvement approach and review unmatched graduates by specialties,

demographics, number of programs applied to, and clinical grading; to oer alternative pathways; and to add

The UGRC recommends the following, organized around nine themes:

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

11

Collaboration and Continuous Quality Improvement

RECOMMENDATIONS

faculty development for clinical advising. Both UME and GME data would identify patterns within the continuum

of medical education that negatively impact unmatched physicians and attrition rates of GME programs. Ideally,

shared resources and innovation across the continuum would be identied and disseminated.

Graduates of U.S. medical schools ll many residency positions, which means GME is constrained by the

decisions made by U.S. medical school admissions committees. However, international medical graduates are

also considered at many programs and provide an opportunity to serve the public good. The committee should

foster research to help program directors understand which applicant characteristics are useful indicators to

address ongoing medical workforce issues. Further changes to the transition should be informed by evidence

whenever possible.

3

The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) should change the

current GME funding structure so that the Initial Residency Period (IRP) is calculated

starting with the second year of postgraduate training. This will allow career choice

reconsideration, leading to improved resident wellbeing and positive eects on the

physician workforce.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Given the timing of the residency recruiting season and the Match, students have limited time to denitively

establish their specialty choice. If a resident decides to switch to another program or specialty after beginning

training, the hospital may not receive full funding due to the IRP and thus be far less likely to approve such a

change. The knowledge that residents usually only have one chance to choose a specialty path increases the

pressure on the entire UME-GME transition. Furthermore, educational innovation is limited without flexibility for

time-variable training.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

12

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

RECOMMENDATIONS

4

Specialty-specic salutary practices for recruitment to increase diversity across

the educational continuum should be developed and disseminated to program

directors, residency programs, and institutions.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Recognizing that program directors, residency programs, and institutions have wide variability in goals, denitions,

and community needs for increasing diversity, shared resources should be made available for mission-aligned

entities, with specialty-specic contributions including successful strategies and ongoing challenges. This

recommendation is intended for specialty organizations to perform workforce evaluations and specically

address diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) associated with specialty-specic disparities in recruitment.

THEME

5

Members of the medical educational continuum must receive continuing

professional development regarding anti-racism, avoiding bias, and ensuring

equity. Principles of equitable recruitment, mentorship and advising, teaching, and

assessment should be included.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Inclusive excellence requires avoiding bias and improving racial equity; these are essential skills for faculty in

today’s teaching. Many physicians lack these skills, perpetuating health disparities, lack of diversity, and learner

mistreatment. ACGME Common Program Requirements already include specic applicable requirements.

This recommendation reinforces the importance of addressing issues related to DEI for all members of the

educational community, including residents starting from orientation. This will ultimately promote belonging,

eliminate bias, and provide social support.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

13

Trustworthy Advising and

Denitive Resources

RECOMMENDATIONS

6

Create an interactive database with veriable GME program/track information and

make it available to all applicants, medical schools, and residency programs and at

no cost to the applicants. This will include aggregate characteristics of individuals

who previously applied to, interviewed at, were ranked by, and matched for each

GME program/track.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Veriable and trustworthy GME program/track information should be developed and made available in an easily

accessible database to all applicants. Information for the database should be directly collected and sources should

be transparent. Each program’s interviewed or ranked applicants reflect the program’s desired characteristics

more accurately than the small proportion of applicants the program matches. Data must be searchable and

allow for data analytics to assist with program decision making (e.g., allowing applicants and their advisors to input

components of their individual application to identify programs/tracks with similar current residents). Applicants

and advisors should be able to sort the information according to demographic and educational features that

may signicantly impact the likelihood of matching at a program (e.g., geography, scores, degree, visa status, etc.).

This database would also provide information on the characteristics of individuals who previously applied to and

matched into various specialties.

THEME

7

Evidence-informed, general career advising resources should be available for all

medical school faculty and sta career advisors, both domestic and international.

All students should have free access to a single, comprehensive electronic

professional development career planning resource, which provides universally

accessible, reliable, up-to-date, and trustworthy information and guidance. General

career advising should focus on students’ professional development; inclusive

practices such as valuing diversity, equity, and belonging; clinical and alternate

career pathways; and meeting the needs of the public. Specialty-specic match

advising should focus on the individual student obtaining an optimal match.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Centralized advising resources, developed in collaboration with specialty societies, should reflect a common core,

with supplemental information as needed, and be evidence-informed and data-driven. This will ll an information

gap and increase the transparency and reliability of information shared with students. Resources should support

the unique needs of traditionally underrepresented, disadvantaged, and marginalized student groups. Guidance

contained in the resources can support faculty in managing or eliminating conflicts of interest related to recruiting

students to the specialty, advising for the Match, and advocating for students in the Match. Advising tools

should incorporate strengths-based approaches to career selection. The resources should include the option of

nonclinical careers without stigma. Three areas of focus are envisioned: basic advising information, general career

advising, and specialty-specic match advising.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

14

Trustworthy Advising and Denitive Resources

RECOMMENDATIONS

Clear and accurate information regarding clinical and nonclinical career choices should be available for all

students. The AAMC’s Careers in Medicine (CiM) platform achieves some of the aims of this recommendation.

The strengths and limitations of CiM should be examined, expanding the content and broadening access to this

resource, including to all students (U.S. MD, U.S. DO, IMG) at no cost throughout their medical school training, or at

a minimum, at key career decision-making points, in order to support students’ professional development. The

public good can be prioritized within this resource with content emphasis on workforce strategies to address

the needs of the public, including specialty selection and practice location as well as alternative nonclinical career

choices. Links to specialty-specic medical student advising resources should also be incorporated.

Basic advising information should be created for all faculty and sta who interact with students to promote

common understanding of career advising, professional development, specialty selection, and application

procedures; introduce the role of specialty-specic advisors as distinct from other faculty teachers; and minimize

sharing outdated or incorrect information with students. General career advising should be dierentiated from

specialty-specic match advising or specialty recruiting. General career advisors require expertise in career

advising; incorporate strengths-based ap-proaches to career selection including the option of nonclinical careers

without stigma; focus on professional development; value diversity, equity, and belonging; incorporate the needs

of the public; and introduce the role of specialty-specic match advisors. Specialty-specic match advisors

should undergo a training process created as part of this resource development that includes equity in advising

and mitigation of bias.

8

Educators should develop a salutary practice curriculum for UME career advising.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Guidelines are needed to inform U.S. MD, U.S. DO, and international medical schools in developing their career

advising programs. Standardized approaches to advising along with career advisor preparation (both general

and specialty-specic) can enhance the quality, equity, and quantity of advising and improve student trust in

the advice. Educators can improve medical student career advising by developing formal guidelines with key

recommendations based upon professional development frameworks and competencies. Implementation

of such guidelines will result in greater consistency, thoroughness, eectiveness, standardization, and equity of

medical school career advising programs to better support students in making career decisions and will lay

the foundation for career planning across the continuum.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

15

Outcome Framework and

Assessment Processes

RECOMMENDATIONS

9

UME and GME educators, along with representatives of the full educational

continuum, should jointly dene and implement a common framework and set of

outcomes (competencies) to apply to learners across the UME-GME transition.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

A shared mental model of competence facilitates agreement on assessment strategies used to evaluate a

learner’s progress, and the inferences that can be drawn from assessments. Shared outcomes language can

convey information on learner competence with the patient/public trust in mind. For individual learners, dening

these outcomes will facilitate learning and may promote a growth mindset. For faculty, dening outcomes will

allow for the use of assessment tools aligned with performance expectations and faculty development. For

residency programs, dening outcomes will be useful for resident selection and learner handovers from UME,

resident training, and resident preparation for practice.

THEME

10

To eliminate systemic biases in grading, medical schools must perform initial and

annual exploratory reviews of clinical clerkship grading, including patterns of grade

distribution based on race, ethnicity, gender identity/expression, sexual identity/

orientation, religion, visa status, ability, and location (e.g., satellite or clinical site

location), and perform regular faculty development to mitigate bias. Programs

across the UME-GME continuum should explore the impact of bias on student and

resident evaluations, match results, attrition, and selection to honor societies.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Recognizing that inherent biases exist in clinical grading and assessment in the clinical learning environment, each

UME and GME program must have a continuous quality improvement process for evaluating bias in clinical grading

and assessment and the implications of these biases, including honor society selection. This recommendation is

intended to mitigate bias in clinical grading, transcript notations, MSPE reflections of remediation, and residency

evaluations. This recommendation is not intended to create requirements for reporting race, ethnicity, gender

identity, sexual identity, religion, or ability of learners as data analysis must be limited to data readily available to

each school.

11

The UME community, working in conjunction with partners across the continuum,

must commit to using robust assessment tools and strategies, improving upon

existing tools, developing new tools where needed, and gathering and reviewing

additional evidence of validity.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Educators from across the education continuum should use shared competency outcomes language to guide

development or use of assessment tools and strategies that can be used across schools to generate credible,

equitable, value-added competency-based information. Assessment information should be shared in residency

applications and a post-match learner handover. Licensing examinations should be used for their intended

purpose to ensure requisite competence.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

16

Outcome Framework and Assessment Processes

RECOMMENDATIONS

12

Using the shared mental model of competency and assessment tools and

strategies, create and implement faculty development materials for incorporating

competency-based expectations into teaching and assessment.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Faculty must understand the purpose of outcomes-focused education, specic language used to dene

competence, and how to mitigate biases when assessing learners. They must understand the purpose and

use of each assessment tool. The intensity and depth of faculty development can be tailored to the amount

and type of contact that individual faculty have with students. Clerkship directors, academic progress

committees, student competency committee members, and other educational leaders require a more in-

depth understanding of the assessment system and how determinations of readiness for advancement

are made. This faculty development requires centralized electronic resources and training for trainers within

institutions. Review of training materials, and completion of any required activities to document review and/or

understanding, should be required on a regular basis.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

17

Away Rotations

RECOMMENDATIONS

13

Convene a workgroup to explore the multiple functions and value of away rotations

for applicants, medical schools, and residency programs. Specically, consider

the goals and utility of the experience, the impact of these rotations, and issues of

equity including accessibility, assessment, and opportunity for students from groups

underrepresented in medicine and nancially disadvantaged students.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Away rotations can be cost prohibitive yet may allow a student to get to know a program, its health system, and

surrounding community. Some programs are reliant on away rotations to showcase their unique strengths to

attract candidates. Given the multifactorial and complex role that away rotations fulll, a committee should be

convened to conduct a thorough and comprehensive review of cost versus benet of away rotations, followed

by recommendations from that review. Non-traditional methods of conducting and administering away

rotations should be explored (e.g., oering virtual away rotations, waiving application fees, or oering away

stipends particularly for nancially disadvantaged students).

THEME

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

18

Equitable, Mission-Driven

Application Review

RECOMMENDATIONS

14

A convened group including UME and GME educators should reconsider the

content and structure of the MSPE as new information becomes available to

improve access to longitudinal assessment data about applicants. Short-term

improvements should include structured data entry elds with functionality to

enable searching.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

The development of UME competency outcomes to apply across learners and the continuum is essential in

decreasing the reliance on board scores in the evaluation of the residency applicant. These will take time to

develop and implement and may be developed at dierent intervals. As new information becomes available

to improve applicant data, the MSPE should be utilized to improve longitudinal applicant information. In addition,

improvements in the MSPE, such as structured data entry elds with functionality to enable searching, should be

explored.

THEME

15

Structured Evaluative Letters (SELs) should replace all Letters of Recommendation

(LORs) as a universal tool in the residency program application process.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

A Structured Evaluative Letter (SEL), which would include specialty-specic questions, would provide knowledge

from the evaluator on student performance that was directly observed versus a narrative recommendation.

The template should be based on an agreed upon set of core competencies and allow equitable access to

completion for all candidates. The SEL should be based on direct observation and must focus on content that

the evaluator can complete. Faculty resources should be developed to improve the quality of the standardized

evaluation template and decrease bias.

16

To raise awareness and facilitate adjustments that will promote equity and

accountability, self-reported demographic information of applicants (e.g., race,

ethnicity, gender identity/expression, sexual identity/orientation, religion, visa

status, or ability) should be measured and shared with key stakeholders, including

programs and medical schools, in real time throughout the UME-GME transition.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Inequitable distribution of applicants among specialties is not in the best interest of programs, applicants, or the

public good. Bias can be present at any level of the UME-GME transition. A decrease in diversity at any point along

the continuum provides an important opportunity to intervene and potentially serve the community in ways

that are more productive. An example of accountability and transparency in an inclusive environment across the

continuum is a diversity dashboard for residency applicants. A residency program that nds bias in its selection

process could go back in real time to nd qualied applicants who may have been missed, potentially improving

outcomes.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

19

Equitable, Mission-Driven Application Review

RECOMMENDATIONS

17

To optimize utility, discrete elds should be available in the existing electronic

application system for both narrative and ordinal information currently presented

in the MSPE, personal statement, transcript, and letters. Fully using technology

will reduce redundancy, improve comprehensibility, and highlight the unique

characteristics of each applicant.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Optimally, each applicant will be reviewed individually and holistically to evaluate merit. However, some

circumstances may require rapid review. The 2020 NRMP program directors’ survey found that only 49% of

applications received an in-depth review. The application system should utilize modern technology to maximize

the likelihood that applications are evaluated in a way that is holistic, mission-based, and equitable.

Currently, applications are assessed based on the information that is readily available, which may place undue

emphasis on scores, geography, medical school, or other factors that perpetuate bias. Adding specic data

gives an opportunity for applicants to demonstrate their strengths in a way that is user-friendly for program

directors. Maximizing the amount of accurate information readily available in the application will increase

capacity for holistic review of more applicants and improve trust during the UME to GME transition. Although

not all schools and programs will align on which information should be included, areas of agreement should be

identied and emphasized.

18

To promote equitable treatment of applicants regardless of licensure examination

requirements, comparable exams with dierent scales (COMLEX-USA and USMLE)

should be reported within the electronic application system in a single eld.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Osteopathic medical students make up 25% of medical students in U.S. schools and these students are required

to complete the COMLEX-USA examination series for licensure. Residency programs may lter out applicants

based on their USMLE score leading many osteopathic medical students to sit for the USMLE series. This creates

substantial increase in cost, time, and stress for osteopathic students who believe duplicate testing is necessary

to be competitive in the Match. A combined eld should be created in the Electronic Residency Application

Service (ERAS) that normalizes the scores between the two exams and allows programs to lter based only on

the single normalized score. This will mitigate structural bias and reduce nancial and other stress for applicants.

19

Filter options available to programs for sorting applicants within the electronic

application system should be carefully created and thoughtfully reviewed to ensure

each one detects meaningful dierences among applicants and promotes review

based on mission alignment and likelihood of success at a program.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Currently, residency programs receive more applications than they can meaningfully review. For this reason,

lters are sometimes used to identify candidates that meet selection criteria. However, some commonly used

lters may exclude applicants who are not meaningfully dierent from ones who are included (e.g., students

who took a dierent licensure examination, students with statistically insignicant dierences in scores, students

from dierent campuses of the same institution, etc.). The use of free text lters increases the risk of not

identifying, or mischaracterizing applicant characteristics. All applications should be evaluated fairly, independent

of software idiosyncrasies. Filters should be developed in conjunction with all stakeholders. Each lter that is

oered should align with the missions and requirements of residency programs.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

20

Equitable, Mission-Driven Application Review

RECOMMENDATIONS

20

Convene a workgroup of educators across the continuum to begin planning for a

dashboard/portfolio to collect assessment data in a standard format for use during

medical school and in the residency application process. This will enable consistent

and equitable information presentation during the residency application process

and in a learner handover.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Key features of a dashboard/portfolio in the UME-GME transition, and across the continuum, should include

competency-based information that aligns with a shared mental model of outcomes, clarity about how

and when assessment data were collected, and narrative data that uses behavior-based and competency-

focused language. Learner reflections and learning goals should be included. Dashboard development will

require careful attention to equity and minimizing harmful bias, as well as a focus on the competencies

and measurements that predict future performance with patients. Transparency with students about the

purpose, use, and reporting of assessments, as well as attention to data access and security, will be essential.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

21

Optimization of Application,

Interview, and Selection Processes

RECOMMENDATIONS

21

All interviewing should be virtual for the 2021-2022 residency selection season. To

ensure equity and fairness, there should be ongoing study of the impact of virtual

interviewing as a permanent means of interviewing for residency.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Virtual interviewing has had a signicant positive impact on applicant expenses. With elimination of travel, students

have been able to dedicate more time to their clinical education. Due to the risk of inequity with hybrid interviewing

(virtual and in person interviews occurring in the same year or same program), all interviews should be conducted

virtually for the 2021-2022 season. Hybrid interviewing (virtual combined with onsite interviewing) should be

prohibited.

A thorough review of the data around virtual interviewing is also recommended. Candidate accessibility, equity,

match rates, and attrition rates should be evaluated. Residency program feedback from multiple types of

residencies should be solicited. In addition, the separation of applicant and program rank order list deadlines in time

should be explored, as this would allow students to visit programs without pressure and minimize influence on a

program’s rank list.

THEME

22

Develop and implement standards for the interview oer and acceptance

process, including timing and methods of communication, for both learners and

programs, to improve equity and fairness, to minimize educational disruption, and

to improve wellbeing.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

The current process of extending interview oers and scheduling interviews is unnecessarily complex and onerous,

with little to no regulation. Applicant stress and loss of rotation education while attempting to conform to some

elements (e.g., obsessively checking emails to accept short-timed interview oers) can be improved with changes

to the application platform, policies, and procedures. Development of a common interview oering/scheduling

platform and creating policies (e.g., forbidding residency programs to over oer/over schedule interviews and

from setting inappropriate time-based applicant replies), would result in important improvements. While these

processes are being developed, residency programs involved in the 2021-2022 residency selection season should

allow applicants 24 to 48 hours to accept or decline an interview oer. In addition, for the 2021-2022 residency

selection season, programs should not oer more interviews to applicants than available interview positions.

Likewise, applicants should not accept multiple interviews that are scheduled at the same time.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

22

Optimization of Application, Interview, and

Selection Processes

RECOMMENDATIONS

23

Innovations to the residency application process should be piloted to reduce

application numbers and concentrate applicants at programs where mutual

interest is high, while maximizing applicant placement into residency positions. Well-

designed pilots should receive all available support from the medical community

and be implemented as soon as the 2022-2023 application cycle; successful pilots

should be expanded expeditiously toward a unied process.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Application inflation is a major problem in the current dysfunction in the UME-GME transition. The 2020 NRMP

program director’s survey found that only 49% of applications received an in-depth review; an unread

application represents wasted time and expense for applicants. Yet doubling the program resources available

for review is not practical. Informational interventions – like improved career advising and transparency – are

unlikely to reduce application numbers signicantly in the context of a high stakes prisoner’s dilemma. In sum,

the current process is costly to applicants and program directors and does not optimally serve the public good.

To address this dysfunction, Coalition organizations and other groups in the medical community should utilize

all available logistic, analytic, and nancial resources to lead and support innovative pilots to reduce application

numbers and concentrate applicants at programs where mutual interest is high, while maximizing applicant

placement into residency positions. Pilots should be based on best available evidence, specialty-specic needs,

potential impact (both positive and negative), and collaboration among stakeholders. Pilot innovations, some

of which are ongoing, could include, but are not limited to, the following: expanding integrated UME-GME

pathways, preference signaling, application caps, and/or additional application or match rounds.

Groups sponsoring pilots should be accountable for using a continuous quality improvement approach to

gather and monitor evidence of eectiveness and equity across applicant groups with historically distinct

application behaviors and outcomes, including United States MD and DO graduates, international medical

graduates, couples applicants, previously unmatched applicants, and individuals belonging to groups that are

underrepresented in medicine.

While pilot studies may vary across specialties, ultimately the redesigned residency application process should

be as consistent as possible across specialties, recognizing that applicants, advisors, and program directors

may be subject to the rules of multiple specialties in the context of combined tracks, couples, and dual

applicants.

24

Implement a centralized process to facilitate evidence-based, specialty-specic

limits on the number of interviews each applicant may attend.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Identify evidence-based, specialty-specic interview caps, envisioned as the number of interviews an applicant

attends within a specialty above which further interviews are not associated with signicantly increased match

rates, across all core applicant types. Create a centralized process to operationalize interview caps, which could

include an interview ticket system or a single scheduling platform.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

23

Educational Continuity and

Resident Readiness

RECOMMENDATIONS

25

Early and ongoing specialty-specic resident assessment data should be

automatically fed back to medical schools through a standardized process to

enhance accountability and to inform continuous improvement of UME programs

and learner handovers.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Instruments for feedback from GME to UME should be standardized and utilized to inform gaps in curriculum and

program improvement. UME institutions should respond to the GME feedback on their graduates’ performance in

a manner that leads to quality improvement of the program.

THEME

26

Develop a portfolio of evidence-based resident support resources for program

directors, designated institutional ocials (DIOs), and residency programs. These will

be identied as salutary practices, and accessible through a centralized repository.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

A centralized source of resident support resources will assist programs with eective approaches to address

resident concerns. This will be especially relevant for competency-based remediation and resident wellbeing

resources in the context of increased demand for support around the UME-GME transition. Access for programs

and program directors will be low/no cost, condential, and straightforward.

27

Targeted coaching by qualied educators should begin in UME and continue during

GME, focused on professional identity formation and moving from a performance

to a growth mindset for eective lifelong learning as a physician. Educators should

be astute to the needs of the learner and be equipped to provide assistance to all

backgrounds.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Coaching can benet a student’s transition to become a master adaptive learner with a growth mindset. While

this transition should begin early in medical school, it should be complete by the time that the student moves from

UME to GME. If a learner does not transition to a growth mindset, their wellness and success will be compromised.

The addition of specic validated mentoring programs (e.g., Culturally Aware Mentoring) and formation of anity

groups to improve sense of belonging should be considered.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

24

Educational Continuity and Resident Readiness

RECOMMENDATIONS

28

Specialty-specic, just-in-time training must be provided to all incoming rst-year

residents, to support the transition from the role of student to a physician ready to

assume increased responsibility for patient care.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

The intent of this recommendation is to level set incoming resident preparation regardless of medical school

experience. Recent research has shown that residents reported greater preparedness for residency if they

participated in a medical school “boot camp,” and participation in longer residency preparedness courses

was associated with high perceived preparedness for residency. This training must incorporate all six specialty

competency domains and be conducive to performing a baseline skills assessment. These curricula might

be developed by specialty boards, specialty societies, or other organized bodies. To minimize costs, specialty

societies could provide centralized recommendations and training could be executed regionally or through

online modules.

29

Residents must be provided with robust orientation and ramp up into their

specic program at the start of internship. In addition to clinical skills and system

utilization, content should include introduction to the patient population, known

health disparities, community service and engagement, faculty, peers, and

institutional culture.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Improved orientation to residency has the potential to enhance trainee wellbeing and improve patient safety.

Residents should have orientation that includes not only employee policies, but also education that optimizes

their success in their specic clinical environment. Residents, like other employees, should be paid for attending

orientation.

30

Meaningful assessment data based on performance after the MSPE must

be collected and collated for each graduate, reflected on by the learner with

an educator or coach, and utilized in the development of a specialty-specic,

individualized learning plan to be presented to the residency program to serve as a

baseline at the start of residency training.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Guided self-assessment by the learner is an important component in this process and may be all that is

available for some international medical graduates. This recommendation provides meaning and importance

for the assessment of experiences during the nal year of medical school (and possibly practice for some

international graduates), helps to develop the habits necessary for life-long learning, and holds students

and schools accountable for quality senior experiences. It also uses the resources of UME to prepare an

individualized learning plan (ILP) to serve as a baseline at the start of GME. This initial ILP will be rened by

additional assessments envisioned as an “In-Training Examination” (ITE) experience early in GME. The time for

this experience should be protected in orientation, and the feedback should be formative similar to how most

programs manage the results of ITEs. This assessment might occur in the authentic workplace and based

on direct observation or might be accomplished as an Objective Structured Clinical Exam using simulation.

This assessment should inform the learner’s ILP and set the stage for the work of the clinical competency

committee of the program.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

25

Health and Wellness

RECOMMENDATIONS

31

Anticipating the challenges of the UME-GME transition, schools and programs

should ensure that time is protected, and systems are in place, to guarantee that

individualized wellness resources – including health care, psychosocial supports, and

communities of belonging – are available for each learner.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

Given that the wellness of each learner signicantly impacts learner performance, it is in the program and public’s

best interest to ensure the learner is optimally prepared to perform as a resident. There should be a focus on

applying resources that are already available rather than depending on the creation of new resources. Examples

of wellness resources include enrollment in health insurance, establishing with a primary care provider and dentist,

securing a therapist if appropriate, identifying local communities of belonging, and other supports that optimize

wellbeing. These resources may especially benet the most vulnerable trainees.

THEME

32

Adequate and appropriate time must be assured between graduation and learner

start of residency to facilitate this major life transition.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

The transition from medical school to residency typically marks a concrete transition from paying for education

to becoming a fulltime employee focused on the lifelong pursuit of professional improvement. This transition is life

changing for many. It often requires a move from one location to another, sometimes across the world. There must

be time for licensing and in some cases, visa attainment. Often this life transition is accompanied by other major

life events such as partnering or childbearing. Once residency starts, the learner may work many hours each

week and may have little time to establish a home. Thus, it is important for wellness and readiness to practice that

adequate time be provided to accomplish this major life transition.

The predictability of this transition must be recognized by both UME and GME institutions, and cooperation on both

sides is required for this transition to be accomplished smoothly. There is a desire to overall better prepare learners

for the start of residency, and an assured transition time would allow related recommendations to be more easily

accomplished.

33

All learners need equitable access to adequate funding and resources for the

transition to residency prior to residency launch.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

As almost every learner graduating from medical school transitions to residency, the need to fund a geographic

move and establishment of a new home is predictable. This nancial planning should be incorporated into medical

school expenses, for example through equitable low interest student loans. Options to support the transitional

expenses of international medical graduates should also be identied. These costs should not be incurred by GME

programs.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

26

Health and Wellness

RECOMMENDATIONS

34

There should be a standardized process throughout the United States for initial

licensing at entrance to residency to streamline the process of credentialing for both

residency training and continuing practice.

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION OF RECOMMENDATION:

To benet the public good, costs to support the U.S. healthcare workforce should be minimized. To this end, all

medical students should be able to begin licensure earlier in their educational continuum to better distribute

the work burden and costs associated with this predictable process. When learners are applying to programs

in many dierent states, the varied requirements are unnecessarily cumbersome. Especially for states where

a training license is required, the time between the Match and the start of the rst year of residency is often

inadequate for this purpose. This is a potential cost saving measure.

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

27

Throughout the transition, learners are being

assessed, including through preclinical course

examinations, rotation evaluations, and

licensure examinations

Medical School

Graduation

13

6

20 19 17

Oered and

Partake in

Interviews

24 22

21

Virtual Interviews for

2021-2022

Standards for

Interview Oer and

Acceptance Process

Interview Limits

23

34

Standardized

Process for Initial

Licensing

Residency

Preparedness

28 29 30

Specialty Specic

Residency

Preparation

Improved Residency

Program Orientation

UME to GME ILP

Hando

Initiate

Support

Structures

Centralized Resident

Support Resources

26

Wellness Resources

for the Transition

31

Major Life

Transitions

32

33

Apply to Many

Programs

Residency Application

Process Innovations

Assured Time Between

UME and GME

Equitable Access to

Funding for Transition

Embed in

Learning and

Work

Environment

Professional

Identity

Formation

The UME-GME transition encompasses a complex ecosystem. As

learners navigate through the UME-GME transition, they interact with

numerous organizations with jurisdiction over specic components of

the process. However, the ecosystem is not governed by a single entity.

9 11 12

Competency Based

Faculty Development

Materials

Improved

Assessment Tools

Common

Competencies

across Transition

Feedback from

GME to UME

25

1

2

3

Committee to

Manage CQI across

Transition

Residency Selection

and Physician

Workforce Research

IRP Reform

The

Learner’s

Journey

Collaboration and Continuous

Quality Improvement

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

Trustworthy Advising and

Denitive Resources

Outcome Framework and

Assessment Processes

Away Rotations

Equitable Mission-Driven

Application Review

Optimizing Application, Interview

and Selection Processes

Educational Community and

Resident Readiness

Health and Wellness

Medical schools and

programs have a

responsibility to promote

equity and diversity across

the continuum

10 5 4

Specialty Specic

Practices to

Increase Diversity

DEI Education

Across the

Continuum

CQI to Mitigate Bias

across Transition

16

Sharing Applicant

Demographics to

Improve Diversity

7

8

Career

Advising

Resources

Career

Advising

Curriculum

Coaching for

Professional

Identity

Formation

27

Prepare Application

Materials

Research

Residency

Programs

Final

Year

Review of Away

Rotations

18 15 14

Interactive

GME

Database

Electronic Application

System Improvements

Review of Filter

Content and Use

Standardized Dashboard

and Portfolio for Learners

MSPE Revision

Structured

Evaluative Letters

Reporting Licensure Exams

in a Single Field

Selection

Process

Hiring and

Credentialing

28

UGRC Process

In the summer of 2020, a Planning Committee of the Coalition selected the

members of the UGRC and charged them with the task of recommending solutions

to identied challenges in the transition. The following is a description of the work

process of the UGRC.

ORIGIN OF THE UGRC

In 2018, a national conversation culminated regarding the use of numeric scores associated with medical

licensing examinations in residency applicant screening and selection. In response, the chief executive ocers of

ve national organizations agreed to co-sponsor an Invitational Conference on USMLE Scoring (InCUS) in March

2019, with the primary goal of reviewing the practice of numeric score reporting. Three recommendations that

emerged focused on the USMLE, however the fourth InCUS recommendation focused on the UME-GME transition:

Convene a cross-organizational panel to create solutions for the assessment and transition challenges from UME

to GME.

In September 2019, a proposal was made to the Coalition to convene a UME-GME Review Committee in line with

the fourth recommendation from InCUS. The Coalition’s members are the national organizations responsible for

the oversight, education and assessment of medical students and physicians throughout their medical careers.

4

As a result, a Planning Committee was created by the Coalition to develop the construct, membership, and charge

of the Review Committee, which would be responsible for recommending solutions to identied challenges in

the UME-GME transition.

1

In January 2020, a call for nominations was issued for individual representatives to the

Planning Committee from undergraduate medical educators, residency program directors, learners, and the

public. The Coalition’s Management Committee selected the individual members of the Planning Committee from

over 60 responses. In addition, organizational representatives from AACOM, AAMC, AOGME, ECFMG, NBME, NBOME,

and OPDA were appointed to the Planning Committee.

The Planning Committee met in March 2020 and identied the construct and structure of the UGRC, developed

a process for selecting its members, and determined the key questions that the UGRC should consider. The

Planning Committee discussed the scope of the UGRC and organized pertinent issues into three broad themes:

(a) preparation and selection for residency, (b) the application process, and (c) overall considerations such as

diversity and specialty specic competencies. The Planning Committee also spelled out the timeline, deliverables,

expectations, and composition of the UGRC. An open call for nominations took place in May and June of 2020 and

the Planning Committee reviewed 183 applications to populate a balanced UGRC that included undergraduate

and graduate medical educators, organizational members, public members, students, and residents. Care was

taken to ensure that multiple perspectives would be represented on the UGRC, including type of degree (DO

and MD), racial and ethnic diversity, range of specialties, geographic distribution, and persons with a focus on

undergraduate medical education (faculty and deans) and graduate medical education (program directors and

DIOs). All UGRC members were selected in July, the co-chairs were named in August, and the UGRC held its rst

meeting in September 2020.

COALITION FOR PHYSICIAN ACCOUNTABILITY

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

29

UGRC STRUCTURE

The UGRC was led by an Executive Committee comprised of the two co-chairs, the lead Coalition sta member,

and the four original workgroup leads. The co-chairs and lead sta member initially created four workgroups to

optimize group dynamics and distribute Committee work in an organized fashion. Because the charge from the

Planning Committee included an ambitious start-to-nish timeline (September 2020 to June 2021), this structure

allowed groups to work in parallel and delve more deeply into assigned tasks. Beyond the individual workgroup

areas of focus, all workgroups also included four overall cross-cutting themes throughout their deliberations:

diversity, equity, inclusion, and fairness; wellbeing; specialty focus; and the public good. Finally, the four original

workgroups were asked to develop research questions and to consider next steps after the UGRC completed its

charge, both of which were needed to help implement nal recommendations and to inform future discussions

out of scope of the UGRC. In February 2021, the co-chairs created a fth workgroup to ensure that the UGRC

appropriately addressed the critical issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Finally, in April 2021, the co-

chairs tasked a sixth “bundling workgroup” to consolidate similar recommendations, sequence interdependent

recommendations, and re-organize the nal recommendations into more cogent themes.

The UGRC was assisted in its work process by generous sta support from Coalition member organizations,

including a project manager, communications director, medical writer, survey analysts, and graphics designers.

Medical librarians searched the literature to support an evidence-informed approach.

UGRC Workgroup Focus Areas

Workgroup A: Ensuring Residency Readiness

General competencies

Selection of residency/specialty eld

Workgroup B: Mechanics of the Application/Selection Process from the UME Perspective

Information sharing

Application content

Application mechanics

Workgroup C: Mechanics of the Application/Selection Process from the GME Perspective

Information sharing

Application process

Interviewing

The Match

Workgroup D: Post-Match Optimization

Optimizing UME by enhancing residency readiness

Optimizing GME by ensuring patient safety

Information sharing

Feedback to UME

DEI Workgroup: Focus on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Bundling Workgroup: Consolidation, Sequencing, and Reorganization of Themes

UME-GME REVIEW COMMITTEE

30

FOUNDATIONAL WORK PROCESS OF THE UGRC

Between September 2020 and June 2021, the entire UGRC met virtually on six separate occasions. Each of

these meetings consisted of multiple sessions spread over two or three days. In addition, a special session of the

UGRC occurred on April 5, 2021, to reconsider several initial recommendations. In between the full Committee

meetings, each workgroup met intermittently to fulll its tasks. A summary was widely distributed to the public

after each Committee meeting to update the community on the UGRC’s progress to date. Further, the UGRC

issued three explicit calls for external stakeholder engagement. The rst one occurred in December 2020 and

focused on envisioning the ideal state of the UME-GME transition. The second occurred in March 2021 and focused

on descriptions of current innovations to improve the UME-GME transition. The third opened in late April 2021 and

specically asked for feedback on the UGRC preliminary recommendations.

The rst virtual meeting of the UGRC occurred in September 2020. Seven consensus ideas quickly emerged

on how to manage the work of the Committee. First, the members agreed that the UME-GME transition

encompassed far more than preparation, application, and selection for residency. This led to an elaboration of