Racial Disparities

in Homeownership

How lending practices have prevented

New Yorkers of color from purchasing homes

and deepened wealth inequality

Office of the New York State

Attorney General Letitia James

October 31, 2023

2

Homeownership is deeply tied to prosperity, wealth, and the American dream. But the credit needed to achieve

homeownership remains out of reach for many people of color, resulting in significant and persistent racial

disparities across New York state. An analysis of recent mortgage data by the Office of the New York State Attorney

General (OAG) found racial disparities at every phase of the lending process for purchase mortgages: at the

submission of loan applications; at the approval or denial of those applications; and, when applications were

approved, in the type and pricing of the loan product. In loan applications for home refinancing, our analysis also

identified similar racial disparities. Reflecting the real barriers to homeownership experienced by New Yorkers of

color, these disparities remained even when controlling for various underwriting considerations, such as credit

score and debt-to-income ratio. The disparities are most pronounced for individual Black and Latino borrowers,

as well as for neighborhoods of color.

OAG found:

• People of color have lower rates of homeownership in New York

» Homeownership in the state is concentrated in white households and neighborhoods. White

households are more than twice as likely to own their home as compared to Black or Latino

households.

» Asian households are also less likely to own their own home as compared to white households.

» Lower homeownership rates for people of color are present in every single region in the state,

showing the pervasive and systemic challenges to closing the homeownership gap.

• Black and Latino people are underrepresented among those who apply for purchase mortgages

» Lenders received disproportionately fewer applications for home purchase loans in 2021 from Black

and Latino applicants: Statewide, 7.6% of purchase applications were from Black residents and 9.5%

were from Latino residents, approximately half of each group’s representation in the overall state

population.

• People of color who apply for loans for purchase mortgages were more likely to be denied

» Applicants of color in New York are denied home purchase mortgages at higher rates than are white

applicants.

» This is true even when controlling for credit score, income, size of loan, debt-to-income ratio, loan-

to-value ratio, and year of application. When controlling for these factors, the probability of a Black

or Asian applicant’s purchase application being rejected in 2021 remained 43% higher than for a white

applicant; Latino applicants were 33% more likely to be rejected than a white applicant.

Executive Summary

3

• When borrowers of color are approved for purchase mortgage loans, they are charged more interest,

costs, and fees

» Black and Latino borrowers received more-expensive loans as compared to white and Asian

borrowers. On average, Black and Latino borrowers were charged over $4,200 more in interest-rate

payments over the course of the loans and an additional $900 in other costs and fees.

1

Looking at

purchase loans originating between 2018 and 2021, across all loans with terms of 30, 25, 20, 15, or 10

years, Black and Latino borrowers faced an estimated $200 million more in interest and other costs

and fees over the course of their loans as compared to white and Asian borrowers.

» Asian borrowers were more likely than white borrowers to have higher average costs and fees across

loan types.

• Racial disparities also exist for refinancing

» Applicants of color have a 21% greater probability of having their refinancing loan applications

denied compared to white applicants with the same application characteristics.

» Refinancing with historically low interest rates during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic

was unequal, with 16,000 fewer applications from neighborhoods of color as compared to white

neighborhoods. This resulted in a loss of an estimated $44 million in annualized savings for

neighborhoods of color across the state.

• A deep legacy of racism and disadvantage has harmed neighborhoods of color, and non-depository

lenders have not solved the problem

» These disparities exist not only between individual applicants and borrowers of different races, but

are also present across neighborhoods: Black and Latino neighborhoods have fewer applications,

higher rates of denial, and costlier loans.

» New private-sector, non-depository lenders have not solved these challenges. They show similar

disparities in rates of applications and denials, as well as costlier fees.

These disparities are not new. They are both persistent and rooted in historic discrimination. Public policy has

thus far failed to address these issues; in fact, public policy has at times created or exacerbated them. Moreover,

while discrimination by individual lenders explains some of these disparities, the problems reflect systemic

failures that will require structural reforms. OAG therefore recommends the following policies to provide robust

support for first-generation homeowners, access to affordable credit opportunities, and lending that serves all

New York communities.

1

“Other costs and fees” refers to all other costs owed to the lender, including closing costs and points. See definitions in Appendix

B for more detail.

4

These disparities confirm that a multi-pronged approach is needed to shrink the racial wealth gap. New York

should:

» Subsidize down-payment support and interest rates for first-generation homeowners to address

generations of policy that have led to significant racial disparities in New Yorkers’ ability to purchase a

home.

» Fund Community Development Financial Institutions that actively deliver responsible, affordable lending

to low-income and historically excluded communities.

» Pass public banking legislation to permit local public banking, which can reinvest money locally and

support financial entities that in turn provide housing loans and support the construction of affordable

housing.

» Strengthen New York’s resources and tools to address discriminatory lending practices.

» Support initiatives to explore forms of retail banking at public institutions that would ensure all New

Yorkers access to basic local banking services, so they can build credit for mortgage lenders.

While this report focuses on mortgage lending, addressing the effects of discrimination will require public-policy

solutions that stretch beyond the availability and affordability of credit. Discrimination in mortgage loans and

homeownership is correlated with disparities in educational opportunities, income, healthcare, support for small

businesses, and infrastructure investments, among other things. While those public-policy areas are beyond the

scope of this report, fully addressing the harms of past discrimination will require significant investments in those

areas as well.

5

Introduction

Homeownership has become a primary source of wealth in our nation.

2

For many Americans, a home is the most

valuable asset they own. While public policy should help make homeownership equally available to members of

all races, it has all too often done the opposite. For decades, public policy has often helped cement institutional

bias in the lending industry. It has segregated access to intergenerational wealth, driving unacceptable levels

of racial inequality. In the 1930s, the practice of refusing loans to people in certain neighborhoods (“redlining,”

explained further below) barred Black Americans from wealth creation while giving white Americans a boost.

3

Racially restrictive covenants existed as another means to exclude minorities from certain neighborhoods.

4

This segregation, solidified by redlining and other discriminatory practices, long outlasted the policies that

created it. During the subprime lending boom that preceded the 2008 financial crisis, lenders filled communities

of color with predatory loan products. During the rampant waves of foreclosures that followed, many Black

Americans lost their homes and a significant portion of their wealth and capital. America’s response to the

financial crisis was nearly two decades of historically low interest rates. This in turn made it easier for those

with access to capital to obtain low-cost financing, allowing them to purchase homes with miniscule interest

rates. Those who survived the foreclosure crisis with their credit and capital intact were able to refinance and

dramatically decrease their mortgage bills. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many also had ample opportunities

to invest in property. These publicly created opportunities were accessible only to those who already had wealth

and capital. This group disproportionately consisted of white Americans. The net result was a further increase in

the disparity between white homeowners and homeowners of color, and a lock in gains at a time when housing

values soared.

2

Kuo, F. Y. (2021, February 16). Homeownership remains primary driver of household wealth. National Association of Home Builders.

https://www.nahb.org/blog/2021/02/homeownership-remains-primary-driver-of-household-wealth

3

Aaronson, D., Hartley, D., Mazumder, B. (2021). The Effects of the 1930s HOLC “Redlining” Maps. American Economic Journal:

Economic Policy, 13 (4): 355-92. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20190414

4

Thompson, C. W., Kim, C., Moore, N., Popescu, R., & Ruff, C. (2021, November 17). Racial covenants, a relic of the past, are still on the

books across the country [radio broadcast episode]. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/11/17/1049052531/racial-covenants-housing-

discrimination

6

In the absence of any systemic attempt to remediate previous discrimination, the racial wealth gap grew larger.

Today, white households in New York are more than twice as likely to own their home as compared to Black or

Latino households.

5

Black New Yorkers at all income levels are also more likely to be denied access to mortgage

credit than are their white counterparts.

6

These racial disparities “reflect generations of exploitative practices

that have had a lasting impact on wealth and creditworthiness.”

7

Our existing policy solutions have not effectively addressed the root causes of homeownership disparities

and the significant structural barriers faced by Black and Latino families in fulfilling the American dream of

homeownership. Nationwide, Black homeownership was among the lowest of any racial or ethnic group and,

according to one analysis, “the Black homeownership rate in 2019 had descended to nearly as low as it was

when racial discrimination in housing was legal.”

8

We can do better to ensure that all New Yorkers have access

to homeownership. We have the opportunity and responsibility to redress some of these racist harms and start

to build a more equitable policy toward housing and wealth. We must proactively provide access to credit to

communities that have been locked out of homeownership and wealth creation throughout the history of our

country. We can begin by supporting new paths toward homeownership today.

This report explores the structural barriers that restrict borrowers of color at multiple places along the path

to homeownership, and afterward. The report looks at racial disparities across the state in several key areas:

overall rates of homeownership, the submission of loan applications for home purchases, the likelihood of those

applications being denied, the types of loan products and terms, and refinancing opportunities. And the report

considers how individual borrowers experience these disparities; how these disparities predominantly affect

neighborhoods of color; and how, with only slight variations across markets, they exist across all regions of New

York.

This report is not exhaustive. While it focuses on several aspects of the lending process that affect equitable

access to home mortgage loans for borrowers of color, it does not explore all of the contributing factors, such

5

See Figure 2 (67% for white households as compared to 32% for Black households and 27% for Latino households).

6

Reynolds, L., Hyun Choi, J., & Perry, V. G. (2022, April 22). How people-based special purpose credit programs can reduce the racial

homeownership gap. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/how-people-based-special-purpose-credit-programs-

can-reduce-racial-homeownership-gap

7

Reynolds, L., Choi, J. H., & Perry, V. G. (2022, April 22). How people-based special purpose credit programs can reduce the racial

homeownership gap. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/how-people-based-special-purpose-credit-programs-

can-reduce-racial-homeownership-gap

8

Asante-Muhammad, D., Buell, J., & Devine, J. (2021, October 13). 60% black homeownership: A radical goal for Black wealth

development. National Community Reinvestment Coalition. https://ncrc.org/60-black-homeownership-a-radical-goal-for-black-

wealth-development

7

as predatory lending, steering practices, and appraisal bias. This report does not fully address other harmful

practices that keep people of color out of homes, such as exclusionary zoning. While these issues are beyond the

scope of this report, they are important and justify further analysis and reform.

9

Closing the racial wealth gap and providing a path to security and stability for all New Yorkers is one of the great

moral issues of our time. Having participated in putting up so many barriers, New York state government has a

responsibility to act now to tear them down. With these proactive policies, we can begin to remedy decades of

wealth inequality, working to create a more just and vibrant New York state community.

Why homeownership matters for racial equality

Homeownership has long been a symbol of economic stability in the United States and a crucial part of the

American dream. In a nationwide survey conducted in March 2022, nearly three-quarters of respondents listed

homeownership as the defining feature of the American Dream, over having a successful career, earning a

college degree, owning a car, having children, or being able to retire.

10

In addition to its symbolic importance, homeownership continues to be a key component of individual and

familial wealth,

11

and a fundamental asset for growing additional wealth. Homeownership comprises a common

— and in some cases, significant — source of the wealth held by American families.

12

Owning a home provides

9

Although this report is focused on lending, solutions that promote fair access to mortgage credit must go hand in hand with

reforms to our nation’s housing markets. Public investments in affordable housing and other policies that combat segregation

and promote affordable development are necessary for many first-generation and first-time homeowners to find a home within

their financial reach. See, e.g., Mironova, O., Stein, S., Hornbach, C., & Udell, J. (2022, November). Pathways to social housing in New

York: 20 policies to shift from private profit to public good. Community Service Society. https://www.cssny.org/publications/ entry/

pathways-social-housing-new-york-20-policies-private-profit-public-good. We must also examine the factors that have led to

soaring rental costs, including multi-family lending practices, that further segregate communities of color and entrench economic

inequality. See, e.g., Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development. (2017, August 15). How to Not End Up on the Public

Advocate’s “The Money Behind the Worst Landlords” List. https://anhd.org/blog/how-not-end-public-advocates-money-behind-

worst-landlords-list

10

Ostrowski, J. (2023, April 19). 73% of aspiring homeowners cite affordability as their primary obstacle. Bankrate. https://www.

bankrate.com/mortgages/homeownership-remains-centerpiece-of-american-dream/

11

Shapiro, T., Meschede, T, & Osoro, S. (2020, February). The roots of the widening wealth gap: Explaining the Black-white economic

divide. Institute on Assets and Social Policy. https://heller.brandeis.edu/iere/pdfs/racial-wealth-equity/racial-wealth-gap/roots-

widening-racial-wealth-gap.pdf; Schuetz, J. (2020, December 9). Rethinking homeownership incentives to improve household financial

security and shrink the racial wealth gap. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/rethinking-homeownership-incentives-to-

improve-household-financial-security-and-shrink-the-racial-wealth-gap

12

Shapiro, T., Meschede, T, & Osoro, S. (2020, February). The roots of the widening wealth gap: Explaining the Black-white economic

divide. Institute on Assets and Social Policy. https://heller.brandeis.edu/iere/pdfs/racial-wealth-equity/racial-wealth-gap/roots-

widening-racial-wealth-gap.pdf. Schuetz, J. (2020, December 9). Rethinking homeownership incentives to improve household financial

security and shrink the racial wealth gap. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/rethinking-homeownership-incentives-

to-improve-household-financial-security-and-shrink-the-racial-wealth-gap. Closing the gaps: Building Black wealth through

homeownership. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103267/closing-the-gaps-building-black-

wealth-through-homeownership_1.pdf

8

13

McCargo, A. & Choi, J. H. (2020, December). Closing the gaps: Building Black wealth through homeownership. Urban Institute.

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103267/closing-the-gaps-building-black-wealth-through-homeownership_1.

pdf

14

See, e.g., Choi, J. H., Zhu, J., & Goodman, L. (2018, October). Intergenerational homeownership: The impact of parental

homeownership and wealth on young adults’ tenure choices. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/

publication/99251/intergenerational_ homeownership_0.pdf

15

See Bhutta, N., Chang, A. C., Dettling, L. J., & Hsu, J. W. (2020). Disparities in wealth by race and ethnicity in the 2019 survey of

consumer finances. The Federal Reserve. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race-

and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.html

16

Percheski, C. & Gibson-Davis, C. (2020). A Penny on the dollar: Racial inequalities in wealth among households with children.

Socius, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120916616

17

Choi, J. H. & Zinn, A. (2022, October 7). New data show Black and Latino homeownership rates increased during the pandemic.

Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/new-data-show-black-and-latino-homeownership-rates-increased-during-

pandemic. It is important to note that, as research indicates, homeownership comes with its own risks and is not a panacea for

closing the racial wealth gap. See, e.g., Schuetz, J. (2020, December 9). Rethinking homeownership incentives to improve household

financial security and shrink the racial wealth gap. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/rethinking-homeownership-

incentives-to-improve-household-financial-security-and-shrink-the-racial-wealth-gap/ (noting risks of homeownership and

proposing policies in addition to increased homeownership to address the racial wealth gap). During the Great Recession, for

example, low-income homeowners and homeowners of color saw much of their wealth destroyed by high-risk and predatory

loan products. Black households lost half of their collective wealth, and Latino households lost two thirds. Shapiro, T., Meschede,

T, & Osoro, S. (2020, February). The roots of the widening wealth gap: Explaining the Black-white economic divide. Institute on Assets

and Social Policy. https://heller.brandeis.edu/iere/pdfs/racial-wealth-equity/racial-wealth-gap/roots-widening-racial-wealth-

gap.pdf. Nevertheless, there remains strong evidence that addressing racial homeownership disparities can play a major role in

building wealth and reducing racial inequality.

borrowers with an asset that can accumulate wealth. Homeownership can provide financial flexibility to not

only withstand financial emergencies, but also support opportunities for economic growth, like providing for

children’s higher education. In addition, children of homeowners are more likely to receive financial support

from parents and information about the homebuying process.

13

Through these and other mechanisms,

homeownership and wealth can reinforce each other and can also be transferred down to future generations

within a family.

14

Given the close relationship between housing and wealth, the persistence of a racial homeownership gap

contributes to a larger racial wealth gap. In 2019, white families in the United States had a median wealth

of $188,200, while Latino families had a median wealth of $36,100, and Black families had a median wealth

of $24,100.

15

The wealth gap is even larger in households with children, where, according to a 2016 study,

Black households hold approximately one cent for every dollar held by white households.

16

Furthermore,

homeownership disparities have only slightly decreased since the COVID-19 pandemic.

17

9

The stark disparities revealed in this report are the direct result of a history of racism. Discrimination in housing

and homeownership have defined our neighborhoods in New York and around the country for generations.

After the Depression of the 1930s,

discrimination in homeownership was

cemented in federal policy with the advent

of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation

(HOLC). HOLC was a government-

sponsored corporation created to assist

homeowners who were on the verge of

foreclosure. In fulfilling that mandate,

however, HOLC canvassed neighborhoods

in 239 cities, including New York City,

Albany, Rochester, Syracuse, Buffalo, and

several smaller cities in New York, and

created color-coded maps for lenders.

18

Green-colored neighborhoods were

treated as low risk and desirable. Other

colors indicated that neighborhoods

were “high risk,” frequently due to “threat

of infiltration of foreign-born, negro, or

lower-grade population.”

19

Lenders were

encouraged to lend to buyers of homes

in the desirable neighborhoods, where

residents then got advantageous loans.

The phrase “redlining” comes from these maps, because red-colored areas indicated that foreign-born or

Black people lived there or nearby, warning lenders that these communities made the properties too risky for

mortgages.

A history of public and private discrimination

Figure 1: Buffalo

Historical Redlining Map

20

18

University of Richmond & Digital Scholarship Lab. (n.d.). Mapping inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. American Panorama.

https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5/39.1/-94.58

19

Hoover, K. (2019), Mapping the legacy of redlining. Crit, 84.

20

University of Richmond & Digital Scholarship Lab. (n.d.). Mapping inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. American Panorama.

https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5/39.1/-94.58

10

Shortly thereafter, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was created. FHA, like HOLC, had an openly pro-

segregation policy; its goal was to support lower-middle-class and middle-class white families.

21

FHA officials

told appraisers to downgrade areas where there was racial mixing, and that “infiltration of inharmonious

racial or nationality groups” would count against a rating.

22

FHA encouraged physical separation between

races by artificial and natural barriers, such as highways.

23

The agency rated neighborhoods by racial quality,

would not sell to Black people in “good” neighborhoods, and refused to insure mortgages in or around Black

neighborhoods.

24

The claims of risk were not backed by facts. In a similar way, Black homeowners with good

credit ratings were systematically refused loans. FHA and the lending industry justified these discriminatory

practices on intrinsic racial stereotypes and an embrace of segregation as stability. The Federal Housing

Underwriting Manual of 1935 stated, “If a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties shall

continue to be occupied by the same social and racial groups.”

25

The Manual warned against “infiltration of

inharmonious racial or nationality groups,” and stated that “all mortgages on properties protected against

[such] unfavorable influences, to the extent such protection is possible, will obtain a high rating.”

26

After the Supreme Court struck down race-based zoning laws, private entities stepped into the void to create

private zoning agreements. A survey of 300 developments built between 1935 and 1947 in Queens, Nassau, and

Westchester Counties found that 56% had racially restrictive covenants; 85% of the larger subdivisions had

them.

27

These covenants were defended by universities, churches, and other institutions.

28

For instance, they were

part of properties sold in Meadowbrook, the Kodak employee community in a Rochester suburb.

29

21

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

22

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

23

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

24

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

25

Federal Housing Authority. (1938). Underwriting and valuation procedure under Title III of the National Housing Act. https://www.

huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Federal-Housing-Administration- Underwriting-Manual.pdf

26

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

27

Dean, J. P. (1947). Only Caucasian: A study of race covenants. The Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics, 23(4), 428-432.

https://doi.org/10.2307/3158842

28

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

29

City Roots & Yale Environmental Protection Clinic. (2020). Confronting racial covenants: How they segregated Monroe County and

what to do about them. https://law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/area/clinic/document/2020.7.31_-_confronting_racial_covenants_-_

yale.city_roots_guide.pdf

11

The post-World War II civil rights movement built on the work of earlier civil rights leaders to right some of

these entrenched wrongs. The movement’s achievements included passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968,

which banned racial discrimination in housing; the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974, which outlawed racial

discrimination in mortgage lending; and the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, which banned redlining.

However, all of these laws suffered from significant underenforcement. In reality, municipalities that wanted to

continue to pursue policies of segregation could do so. Moreover, the laws failed to do anything to affirmatively

remedy the accumulated harm from decades of discrimination.

Forty years of redlining and disinvestment in urban centers led to uninhabitable homes.

30

That was followed by

“urban renewal programs” that destroyed neighborhoods, and then by a voucher model in the late 1980s. The

extreme racial inequality was not only left unaddressed; it was often exacerbated by these policies.

During the early 2000s, predatory lending soared, and Black Americans were among the most harmed.

Subprime lenders targeted Black Americans of all income levels. Mainstream financial institutions, which had

previously ignored these neighborhoods, now flooded them with high-cost, predatory mortgage products.

These institutions claimed to be increasing access to credit, but the products often stripped Black homeowners

of equity or trapped them in high-cost mortgages that would ultimately cause more harm than good. Higher-

income Black Americans were three times as likely as higher-income whites to be victims of subprime loans.

31

In

Buffalo, 75% of all refinance loans to Black borrowers were subprime.

32

When the housing bubble collapsed, Black

homeowners were left holding the bag. Their wealth was destroyed.

30

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

31

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

32

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

12

Methodology

OAG used several data sources to analyze disparities in homeownership and access to mortgage credit. We

used census data for general homeownership rates, neighborhood demographics, number of homeowners in

neighborhoods, and refinancing utilization. We also drew from data collected in accordance with the Home

Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA). This included both public data, as well as non-public credit scores from

institutions regulated by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the Department of Housing and

Urban Development (HUD), and the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA). In addition, we used Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) data for bank-branch locations.

For our analysis, we looked at each step of the home-loan process to identify where disparities occur for

applicants of color. Throughout the report, we focused on differences in outcomes for applicants and borrowers.

For applicants who were denied a loan, we controlled for several underwriting factors to determine if there was

a statistically significant difference between applicants of color and white applicants with similar characteristics.

When calculating the added cost borne by borrowers of color for home loans, we removed outliers by limiting

our analysis to loans that fell within the middle of the range of values for each loan type (i.e., limited to loans

within the second and third quartiles) but did not otherwise control for these factors.

This report defines applicants, borrowers, households, and neighborhoods of color as follows:

Applicants – anyone who applied for a loan and was either accepted or denied (action taken codes 1, 2,

and 3 in HMDA data). An applicant of color in this report refers to an applicant who is not a non-Hispanic

white person, or a couple that includes one person who is not a non-Hispanic white person.

Borrowers – any applicant with a loan that was originated (action taken code 1), meaning that a borrower

applied for a loan and the lender approved their application. A borrower of color in this report refers to a

borrower who is not a non-Hispanic white person, or a couple that includes one person who is not a non-

Hispanic white person.

Neighborhoods – census tracts, which are commonly used geographic areas monitored by the U.S.

Census Bureau. A neighborhood of color refers to a neighborhood that is less than 50% white non-Hispanic.

Households – a POC household (or household of color) refers to a household where the race of the

householder is not non-Hispanic white. A householder is defined by the Census Bureau as “the person, or

one of the people, in whose name the home is owned, being bought, or rented.”

33

While homeownership disparities exist across all applicants and borrowers of color as compared to

white applicants and borrowers, the disparities differ in type and severity. This report aims to illuminate

where disparities exist across all communities of color, while also directly speaking to the largest gaps

in homeownership and home loan access and experience. This is why our report sometimes compares

communities of color to white communities. At other times, we focus on Black and Latino applicants and

borrowers specifically, where we observed different or especially severe disparities when compared to white

applicants and borrowers.

33

United States Census Bureau. (n.d.). Householder. In Glossary. Retrieved August 22, 2023, from https://www.census.gov/

glossary/?term=Householder

13

Present-day statewide disparities resulting from decades

of discrimination

The relentless history of housing and lending discrimination has unsurprisingly yielded staggering disparities

today, both among households of different races and neighborhoods of different races. Racial differences

in homeownership in New York are significant (Figure 2): Among white households, 67% own their homes,

compared to only 34% of households of color according to the Census’s American Community Survey (ACS).

Homeownership rates are particularly low among Black households (32%) and Latino households (27%).

34

Nationwide, more people of all races own homes and racial disparities in homeownership are smaller than in

New York, although still unjustifiably large: approximately 72% of homes were owned by white households, as

compared to approximately 43% for Black households and approximately 51% for Latino households.

35

34

2020 American Community Survey five-year estimates: This information is collected by the Census Bureau and concerns social,

economic, housing, and demographic statistics for people and communities in the United States. We used these data points for

the homeownership statistics included in this report. See Appendix A for the variables we used.

35

Chugg, H. (2023, May). The homeownership gap between Black and white families in the United States. Ballard Briefs. https://

ballardbrief.byu.edu/issue-briefs/the-homeownership-gap-between-black-and-white-families-in-the-united-states

36

A metropolitan statistical area (MSA) is a geographic area defined by the federal government to calculate certain federal

statistics, such as home-mortgage statistics submitted in accordance with the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. As of July

2023, there are 387 metropolitan statistical areas in the United States, and 14 in the state of New York, shown in Figure 3. The

United States Office of Management and Budget Standards. (n.d). Metropolitan and Micropolitan. United States Census Bureau.

Retrieved August 22, 2023, from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/metro-micro.html

Figure 2: Percent of occupied units that are owner occupied statewide

Asian

70

60

50

40

30

10

10

0

Black Latino Other

Householder Race

White POC

Percent

Patterns of lower homeownership for borrowers of color are present in every metropolitan statistical area (MSA)

36

in the state, as shown in Figure 3. And while some MSAs have particularly stark disparities, the trend across all

MSAs highlights that the problem is pervasive and structural statewide.

Source: 2020 ACS Data

14

Figure 3: Rates of homeownership in white households versus households of color in New York state

80

60

40

20

0

Figure 4: Percent that white homeownership rate is greater than POC homeownership rate

Source: 2020 ACS Data

Percent

Source: 2020 ACS Data

15

Closed doors and wealth extraction

New Yorkers of color are blocked from accessing credit at all stages of home buying and ownership. Looking at

data for home purchasing and refinancing from 2018 to 2021, OAG found disparities for applicants, borrowers,

and communities of color as compared to their white counterparts. These disparities were evident in every phase

of lending:

» percentage of submitted applications for purchase mortgage

» likelihood that applications were denied

» terms, rates, and fees for loans

» homeowners’ applications for refinancing

A problem in the pipeline: Black and Latino people are

underrepresented among mortgage applicants

OAG first looked at applications for home-purchase loans across the state. For the majority of homeowners,

applying for a mortgage is a necessary step to financing a home purchase. Disparities in applications can signal

several crucial structural problems in the lending market, such as the failure of lenders to open branches or

market in communities of color. In addition, while financial institutions commonly build meaningful relationships

in communities, they rarely do so in communities of color.

37

Added to the complexity of the mortgage lending

process and a recent history of predatory lending by large financial institutions, these factors have contributed

to mistrust of these institutions among communities of color. These are yet more barriers faced by these

communities, in addition to the legacy of historical segregation we described earlier, other types of overt or

implicit discrimination, and racial disparities in wealth and other factors affecting credit.

OAG’s analysis found that, statewide, lenders received fewer applications from Black and Latino applicants than

their proportion of the state population, with 7.6% of purchase applications from Black applicants and 9.5% from

Latino applicants. That is approximately half of each group’s representation in the overall population.

Table 1: Proportion by race for general population compared with 2021 mortgage applications

Race Proportion of state

population

Proportion of home-

purchase applications

Asian 8.8% 16.4%

Black 14.5% 7.6%

Latino 19.7% 9.5%

Other race, or mixed-race couples 0.2% 5.9%

White 56.9% 60.5%

37

For example, in United States v. Park National Bank, the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice alleged that a

lender engaged in “limited marketing and outreach” to communities of color and “its services were more easily available” in

white neighborhoods. See Complaint at 7-8, United States v. Park National Bank, No. 23-CV-00822 (S.D. Ohio 2023).

16

A look at the distribution of bank branches further illustrates the broken relationship between neighborhoods of

color and lenders. The map of Rochester in Figure 5 shows bank branches almost exclusively located in majority-

white neighborhoods.

38

Most residents in neighborhoods of color must travel much farther than their white-

neighborhood counterparts to reach a bank. This pattern is not unique to Rochester: We see similar distributions

across the state.

Given financial institutions’ lack of investment in neighborhoods of color, there is little wonder that so few Black

and Latino people apply for mortgage loans. This pattern is sadly consistent with the experience of Black and

Latino borrowers in later phases of the home-purchase process. The dearth of mortgage applications from these

groups seems to be a symptom of a barrier that is not seen in applications from Asian or white New Yorkers, and

it contributes to the significant racial disparities in homeownership that exist across the state.

38

Bank branch location data is as of June 2022.

Figure 5: Bank branches in Rochester

Source:

FDIC June 2022,

HMDA 2019-2021,

2020 ACS Data

17

More applicants of color are denied credit for home-

purchase loans

OAG found that New Yorkers of color were denied home-purchase loans more frequently than were white

applicants. Looking at data between 2018 and 2021,

39

before controlling for other factors, we see that all people

of color were denied purchase loans more often than white applicants, with Black applicants denied 23% of the

time and white applicants denied 14% of the time. Latino applicants were denied 20% of the time.

Disparities remain even when accounting for credit scores (Figure 6).

40

When we group applicants by credit-score

range, we see that applicants of color were denied more frequently than white applicants in every range. Denial

rates have the least variation across race and ethnicity at the lowest credit scores (lower than 670), while still

showing a difference between applicants of color and white applicants. The disparity increases at higher credit

scores, where denial rates for Black and Latino applicants are often near double, and in some cases more than

double, that of white applicants.

39

This section relies on HMDA data for 2018-2021 for institutions regulated by CFPB, HUD, or NCUA. Home Mortgage Disclosure

Act (HMDA). (2018-2021). HMDA Data. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/

hmda

40

OAG obtained from CFPB HMDA data that includes credit scores for 2018-2021, and includes institutions regulated by CFPB,

HUD, and NCUA.

Figure 6: Denial rate by race, purchase loans only

Source: 2018-2021 HMDA

for institutions regulated

by CFPB, HUD, or NCUA

Credit score

Percent

25

20

15

10

5

0

18

We also found that these disparities remain even after controlling for additional factors beyond credit score. To

conduct this analysis, we used a logistic regression to model application-rejection rates after controlling for year

of application as well as credit score, loan amount, debt-to-income ratio (DTI), loan-to-value ratio (LTV), and

applicant income. These are metrics typically used by lenders to evaluate the strength of a purchase mortgage

application. We considered applications for primary-residence home-purchase loans that were secured by a first

lien and that resulted in origination, approval (but not acceptance), or denial. The applicants had the following

characteristics: income less than $1,000,000,

41

DTI of 0-900, credit score of 300-850, and LTV of 0-500.

To conduct the analysis, we used the following profile to represent an average

42

applicant of color in 2021: an

applicant with a credit score of 731, DTI of 42, LTV of 84, and income of $133,796, seeking a loan of $432,280.

When we analyzed applicants of different races with this same profile, we still found startling disparities, with

Black and Asian applicants 43% more likely to be rejected than a white applicant, and Latino applicants 33%

more likely to be rejected.

On average, applicants of color have a 38% higher probability of being denied a loan

than white borrowers. Table 2 shows the probability of denial for applicants of various races and ethnicities.

Although the table shows probabilities only for the year 2021, we found discrepancies in all years for which we

analyzed data (2018 through 2021).

41

Applicant income is conventionally reported in thousands. OAG tested limiting applicant income to under 1,000,000 (equivalent

of 1 billion if reported as intended) and 1,000 (equivalent of 1 million if reported as intended). The regression results were the

same.

42

We find similar disparities when using the median values instead of average.

19

43

The table shows the probability of denial for an application with the indicated race and the following characteristics: loan

amount $432,280, credit score 731, DTI 42, LTV 84, and income $133,796.

44

The column “Percentage higher than probability of denial of white applicant” is the difference between the denial rate and the

denial rate for white borrowers, divided by the denial rate for white borrowers.

45

Lenders who provide more support and guidance through the mortgage process may ultimately approve a previously denied

applicant. A recent analysis by Freddie Mac looked at applicants who were denied their first application for a loan. Some of those

applicants were later approved. The analysis found that “whereas 78% of subsequently approved applicants said they reapplied

with the same lender, only 17% of non-approved applicants said they expected to reapply with the same lender.” It noted that this

difference “suggests that lenders have an opportunity to provide more educational and consultative resources to help turn more

mortgage denials into approvals.” Freddie Mac. (2022, August 17). What do borrowers do when a mortgage application is denied?

https://www.freddiemac.com/research/consumer-research/20220817-what-do-borrowers-do-when-mortgage-application-

denied. This indicates that lender engagement may play a role in applicant success. However, many lenders fail to provide such

support.

Table 2: Probability of denial in 2021 for purchase-loan application

with the same applicant characteristics

43, 44

Applicant race Probability of denial

Percentage higher than

probability of denial of

white applicant

White 7.4% N/A

Asian 10.6% 43%

Black 10.6% 43%

Latino 9.9% 33%

Multiple races 8.6% 16%

Identifying as another race 15.6% 110%

Race unavailable 11.0% 48%

All POC applicants 10.3% 38%

The higher likelihood of denial for borrowers of color is seen across the state. As shown in Figure 7, in every MSA

in New York, applicants of color were more likely to be denied loans for purchase mortgages than are white

applicants. Buffalo, Glen Falls, and Rochester have the largest disparities. For the Buffalo MSA, an applicant of

color is 89% more likely to be denied a home-purchase loan than a white applicant with the same profile. In Glen

Falls, a Black applicant is 78% more likely to be denied. And in Rochester, a Black applicant is 68% more likely to

be denied. Even in MSAs with relatively lower disparities, an applicant of color is still 10-20% more likely than a

white applicant to have their application denied.

45

20

Figure 7: Denial rate by applicant race in 2021, predicted at average

loan amount, credit score, DTI, LTV, and income for POC applicants

(purchase loans)

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

A note on the limitations of this report: Our analysis accounts for the most commonly used factors for evaluating

the creditworthiness of an applicant. We did not have access to every factor considered in the underwriting

process; underwriters have additional information available, such as liquidity, attributes of the home, and

applicant credit history, that may play a role in the home-purchase mortgage application process.

However, we did model the data using tools that took additional variables into account, such as automated

underwriting systems (AUS) used by purchasers or guarantors of some loans. Some recent studies have included

the results of these types of financial models. We tested additional models, including using AUS results, to see if

the additional information would contradict our findings of disparities in denials of home-purchase loans. Even

with this finetuning of our data, we consistently found statistically significant differences by race for mortgage

denials.

Source: 2018-2021 HMDA

for institutions regulated

by CFPB, HUD, or NCUA

Percent

21

Black and Latino borrowers are more likely to use Federal

Housing Administration (FHA) loans

Our analysis also found that Black and Latino borrowers were more likely to use Federal Housing Administration

(FHA) loans.

FHA loans can help bridge a critical gap for borrowers who have less access to capital for a down payment.

However, FHA loans often come at a steeper interest rate than conventional loans. In addition, FHA lenders often

require borrowers to purchase additional insurance, private mortgage insurance (PMI) that further increases

the cost of the loan. For this reason, borrowers who could put down a larger down payment often choose to do

so and may pay less over the course of the loan. Our analysis shows that people of color had more FHA loans

across all credit scores. This difference is particularly concerning at the higher end of credit scores — statewide,

more than 10% of Black borrowers with high credit scores (800-850) have FHA loans, compared to only 1.5% of

white borrowers.

Figure 8: Percent of loans that are FHA by race, purchase loans only

Credit score

Percent

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Source: 2018-2021 HMDA

for institutions regulated

by CFPB, HUD, or NCUA

The disproportionate use of FHA loans by Black and Latino borrowers likely reflects a variety of issues. As noted

earlier, although FHA loans tend to cost more over the life of a loan, they require a lower down payment than do

conventional loans. This may contribute to the reason why Black and Latino borrowers, who have historically

been denied the opportunity to build wealth and who therefore often lack access to capital for down payments,

are overrepresented among FHA borrowers. The problem may be particularly acute in New York City and Long

Island, where home prices are higher and therefore more likely to require higher down payments. In these

regions, racial disparities in the use of FHA loans are the highest.

22

46

See, e.g., California Reinvestment Coalition, Empire Justice Center, Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance, Neighborhood

Economic Development Advocacy Project, Ohio Fair Lending Coalition, Reinvestment Partners, & Woodstock Institute. (n.d).

Paying more for the American dream VI: Racial disparities in FHA/VA lending. Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance. https://

mahahome.org/sites/MAHA-PR1/files/attachment-files/Paying%20More%20VI.pdf

47

Categorized in the HMDA data as “other costs and fees”.

In addition, prospective homebuyers’ relationships with financial institutions likely play an important role.

Borrowers of color may be more likely to get FHA loans if they cannot access lenders that offer a full range of

mortgage products — even when these borrowers may qualify for other products. And, in some instances,

lenders may actually steer borrowers of color into FHA loans.

46

In a similar way, these borrowers may be unaware

of the costs of different loan types because they have less access to lenders and information. Lenders play a

significant role in educating new home purchasers about their options.

Many factors contribute to the disproportionate use of FHA loans by Black and Latino borrowers. The net result is

steeper costs for homeownership.

Cost of credit: A heavier burden on borrowers of color

Mortgage loans have several features that dictate the total cost of the loan other than fees due at closing.

Interest rates vary across loan types and lengths, and for adjustable-rate mortgages, can vary over the course of

the loan. Mortgage loans also have costs and fees associated with loan processing and origination, and points

to be paid for lower interest rates for purchase and refinancing loans. Together, these loan attributes make up

the total cost of the loan.

Thanks to newly available HMDA data, we have been able to take a more detailed look into additional costs

and fees than in the past. We found disparities in the cost of loans for borrowers of color compared to white

borrowers. All borrowers of color pay higher costs and fees than white borrowers. Black and Latino borrowers

hold loans with higher interest rates than do white and Asian borrowers.

In general, for originated purchase loans, borrowers of color pay higher costs and fees

47

than white borrowers

(Figure 9). This is true across all common loan types, but most extreme for FHA loans, which as discussed

previously are more commonly used by certain borrowers of color.

23

Figure 9 shows average “other costs and fees” by race and loan type for home purchase loans from 2018 to

2021. To arrive at these figures, we limited the analysis population to loans with LTV between the 25th and 75th

percentile for each loan type: conventional, FHA, Farm Service Agency (FSA) or Rural Housing Service (RHS), or

Veterans Benefits Administration (VA). FHA loans have significantly higher costs and fees for all borrowers. On

average, borrowers of color experience higher costs and fees than white borrowers across all loan types.

Applicant race Conventional FHA FSA/RHS VA

Asian $6,080 $12,267 $7,660 $11,551

Black $5,943 $13,000 $7,463 $8,284

Latino $5,991 $12,458 $5,402 $7,725

Multiple Races $5,450 $10,801 $5,733 $8,001

Other Race $5,432 $9,849 N/A $4,989

Race Unavailable $5,591 $8,624 $4,166 $6,457

White $4,936 $6,842 $3,984 $5,798

All Borrowers $5,260 $9,041 $4,085 $6,339

This table shows loan costs for loans with an LTV within the interquartile range (middle quartiles) for each loan type. This is 75-90 for

conventional loans, 96.5 for FHA loans, 97.6-10 for FSA/RHS, and 100 for VA.

Figure 9: Other fees: white vs. POC

Table 3: Other fees: white vs. POC

Source: HMDA, 2018-2021

Other costs and fees

Proportion of originations

24

Credit score

All of these loan type categories (except FSA/RHS, likely due to the small size of this subpopulation, which makes

up less than 1% of the overall population — see Appendix C) have statistically significant differences between

costs and fees for white borrowers and borrowers of color as a group.

The following charts show the same information as the table above showing rates of utilization for the most

common racial demographics.

Figure 10: Other fees by race, purchase loans

Conventional

14000

12000

10000

8000

6000

4000

2000

0

Loan type

FHA USDA RSH/FSA VA

These differences are not explained by credit score. The chart below shows differences in other costs and fees by

credit score band showing that white loan applicants are paying less in every credit score range (Figure 11).

Source: HMDA, 2018-2021

Figure 11: Other fees by race, purchase loans

12000

10000

8000

6000

4000

2000

0

Source: 2018-2021 HMDA

for institutions regulated

by CFPB, HUD, or NCUA

Dollars

Dollars

25

We also looked at interest rates for approved, conventional fixed-rate purchase loans, which make up the vast

majority (79%) of fixed-rate purchase loans. Here, consistent with the higher costs and fees charged to Black and

Latino borrowers, these same borrowers had a statistically significant higher interest rate than white borrowers.

Black and Latino borrowers were given interest rates of 3.69%, while white and Asian borrowers were given

interest rates of 3.63%.

To calculate the impact of the higher total loan costs on Black and Latino borrowers, we limited our analysis to

approved 30-year conventional fixed-rate loans. We calculated the difference between the cost of credit for the

average Black and Latino borrower using the average loan amount, interest rate, and costs and fees for Black

and Latino borrowers. We then compared that to the average cost of credit for Asian and white borrowers using

the analogous quantities.

Table 4 shows the average rates across demographics, as well as the number of borrowers. We calculated the

approximate value of the additional cost borne by Black and Latino borrowers from 2018 to 2021 for this loan

type. Black and Latino borrowers who sought home-purchase loans could expect nearly $170 million dollars in

additional interest payments and $37 million in costs and fees. This means that Black and Latino New Yorkers can

expect to spend over $200 million more for home-purchase loans over the course of their loans.

When we looked at the costs associated with refinancing and cash-out refinancing, we found that additional

loan costs for Black and Latino borrowers increase almost three-fold. Across all fixed-rate loan types with terms

of 30, 25, 20, 15, or 10 years, Black and Latino borrowers who took out loans between 2018 and 2021 can expect to

overpay more than $600 million in interest and other costs and fees over the course of their loans.

Table 4: Differences in cost of credit for Black and Latino borrowers compared to white and Asian borrowers,

for 30-year fixed rate conventional mortgages originating between 2018 and 2021

Purpose Purchase Refinancing Cash-out refinancing

Average loan amount for Black and

Latino borrowers

$351,779.66 $396,409.58 $374,734.33

Average Black/Latino interest

3.69 3.35 3.80

Average White/Asian interest

3.63 3.23 3.66

Average difference in interest paid

over life of loan

$4,284.82 $9,520.55 $11,019.80

Average difference in other costs and

fees

$937.74 $1,728.99 $1,667.72

Average interest plus other costs and

fees

$5,222.56 $11,249.54 $12,687.51

Total number of loans

282,589 110,124 79,154

Number of Black and Latino borrowers

39,648 16,771 13,927

Total interest overpayment for Black

and Latino Borrowers

$169,884,407.27 $159,669,110.53 $153,472,722.27

Other costs and fees overpayment

$37,179,676.06 $28,996,905.76 $23,226,296.76

Total overpayment for Black and

Latino Borrowers

$207,064,083.32 $188,666,016.29 $176,699,019.04

26

Failure to serve: the neighborhood impact

At each stage of the homeownership process, Black and Latino borrowers are disproportionately taxed. This

economic punishment starves communities of resources and deprives borrowers of color of the power to amass

wealth. As we described earlier, neighborhoods of color, particularly Black and Latino neighborhoods, have been

historically segregated by racist housing policies and bifurcated by physical infrastructure, such as highways.

Federal government programs to support homeownership and wealth-building benefited white families, who

have tended to congregate in suburban locales, rather than Black and Latino families, who have tended to live in

urban centers.

Such choices by the national government, facilitated by and combined with private disinvestment, such as the

loss of jobs beginning in the 1970s,

48

have further concentrated poverty in segregated urban areas. Despite

discrimination being prohibited, communities of color remain under-resourced and undervalued. In 2021, the

average value of a New York City home paid for by financing was $824,000 in a neighborhood of color, versus

$1.23 million in a majority-white neighborhood.

49

In Rochester, the average value of a home paid for by financing

was $114,000 in a neighborhood of color, versus $231,000 in a majority-white neighborhood.

The stark racial disparities for individual borrowers we have described are clearly reflected more broadly

in neighborhoods of color, starting with ownership rates. When looking at the predominant race

50

in the

neighborhood (rather than race of the people in the home, as we did earlier in this report), we see the lowest

homeownership rates in Latino, Black, and other neighborhoods of color. In New York, white neighborhoods

have three times the homeownership rate of Latino neighborhoods.

48

See, e.g., Kalleberg, A. L. (2011). Good jobs, bad jobs: The rise of polarized and precarious employment systems in the United States,

1970s-2000s. Russell Sage Foundation.

49

According to property value in 2021 HMDA data. Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. (2021). HMDA Data

Publication. https://ffiec.cfpb.gov/data-publication/2021

50

We define “predominant race” as a neighborhood where that race constitutes more than 50% of its residents.

Figure 12: Percent of occupied units that are owner occupied statewide

Percent

Asian

Black

Latino None

(mixed)

Predominant Race of Neighborhood

White

POC

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Source: ACS, 2020

27

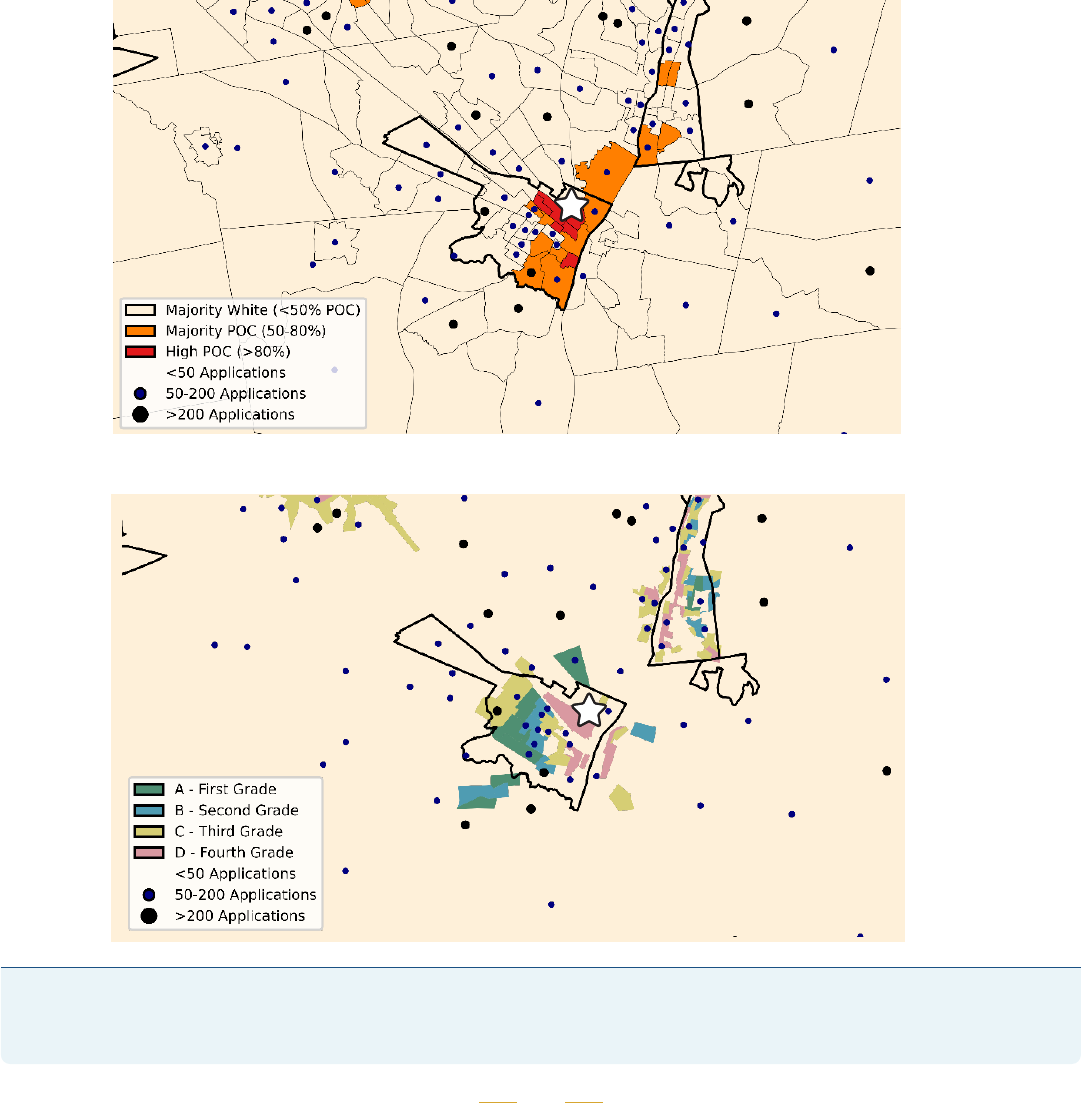

Fewer applications from neighborhoods of color

Across the state, lenders receive home-purchase applications at higher rates from predominantly white

neighborhoods than from neighborhoods of color. In the following map of the Albany MSA (Figure 13), there are

fewer applications in neighborhoods with over 80% people of color as compared to the rest of the MSA. This

pattern is reflected in the historical HOLC redlining map, where Grade A (green) indicates the least-risky grade

and Grade D (red/pink) indicates the riskiest grade, where HOLC discouraged banks from lending. For example,

as shown by the white stars in Figures 13 and 14, certain areas that were redlined for having a high percentage

of residents of color are the same areas today with a high percentage of residents of color showing few

applications for home-purchase mortgages.

Figure 13: Albany Schenectady Troy

Source: 2019-2021 HMDA

purchase applications,

ACS 2020

Source: 2019-2021 HMDA

purchase applications,

Mapping Inequality from

University of Richmond

Figure 14: Albany Schenectady Troy

51

51

University of Richmond & Digital Scholarship Lab. (n.d.). Mapping inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. American Panorama.

https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5/39.1/-94.58

28

Figure 15: Nassau County

Figure 16: Suffolk County

Sources: 2019-2021 HMDA purchase applications, ACS 2020

This pattern is reflected across the state, where we consistently see higher rates of applications from majority-

white areas. For example, Long Island shows a clear lack of applications from neighborhoods of color at the

western ends of both Nassau County (Figure 15) and Suffolk County (Figure 16).

29

Figure 17: Rochester

Figure 18: Rochester

52

Sources: 2019-2021 HMDA purchase applications, Mapping Inequality from University of Richmond, ACS 2020

The Rochester MSA, like Long Island and Albany, has fewer mortgage applications from communities of color

within city limits (Figure 17). The area denoted with a white star is colored red due to its high concentration of

residents of color. This area has seen fewer purchase mortgage applications, and as shown in the map in Figure

18, was one of the areas redlined by HOLC.

52

Historical redlining boundaries from: University of Richmond & Digital Scholarship Lab. (n.d.). Mapping inequality: Redlining in

New Deal America. American Panorama. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5/39.1/-94.58

30

Figure 19: Denial rate by neighborhood race in 2021, predicted at average

loan amount, credit score, DTI, LTV, and income for POC applicants

(purchase loans)

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Higher denial rates in neighborhoods of color

Applicants applying for home-purchase loans from neighborhoods of color were more likely to be denied a

loan than applicants from a majority white neighborhood in each MSA in the state. Statewide, applicants from

neighborhoods of color were more than 49% more likely to be a denied a loan, even when accounting for loan

amount, credit score, DTI, LTV, income, and application year. This is even more stark in several parts of the state.

In the Buffalo MSA, applicants from neighborhoods of color are 151% more likely to be denied. In the Dutchess/

Putnam MSA, applicants from neighborhoods of color are 72% more likely to be denied, 72% more likely in

Rochester, 66% more likely in Albany, and 59% more likely in Syracuse.

Sources: 2019 ACS and

2018-2021 HMDA for

institutions regulated by

CFPB, HUD, or NCUA

Percent

31

Table 5: Probability of denial by MSA in 2021 for purchase loan with the same application

characteristics, by majority race of residents in the census tract

53

MSA

Predicted

denial rate for

POC tract

Predicted denial

rate in white

tract

Percentage of higher

probability to be denied

versus white tract

Albany-Schenectady-Troy 10.4% 6.2% 66%

Buffalo-Cheektowaga-Niagara Falls 16.0% 6.4% 151%

Dutchess County-Putnam County 15.9% 9.2% 72%

Kingston 12.5% 11.1% 12%

Nassau County-Suffolk County 11.3% 8.3% 37%

New York State 12.0% 8.0% 49%

New York-Jersey City-White Plains

54

11.6% 8.8% 33%

Rochester 9.7% 5.6% 72%

Syracuse 10.0% 6.3% 59%

Utica-Rome 12.0% 8.7% 38%

Inequality in refinancing for neighborhoods of color

For more than a decade, the United States saw historically low interest rates,

55

which allowed homeowners with

mortgages to refinance their mortgages, decreasing both their monthly housing expenses and overall cost of

their loan.

56

Yet not all homeowners experienced refinancing opportunities equally. As we can see in the data, this

is another area where racial disparities exist in terms of access, terms, and costs.

Homeowners in neighborhoods of color are less likely to seek refinancing opportunities to renegotiate their

mortgage terms to obtain better rates. Of those who try, more homeowners in neighborhoods of color are

denied than are homeowners in majority-white neighborhoods.

Figure 20 shows a box plot of the lower rate of refinancing applications from neighborhoods of color versus

white neighborhoods. Looking at individual census tracts within MSAs, we compared the number of existing

mortgages, according to 2019 census data, to the number that had refinancing applications in 2020-2021. These

53

The table shows the probability of denial for an application with the average characteristics of a POC borrower in the indicated

MSA (loan amount, credit score, DTI , LTV, and income).

54

This MSA is called the New York-Jersey City-White Plains MSA; however, we excluded New Jersey purchase loans from our

calculations.

55

Russell, J. (2023, January 18). Historical mortgage rates in the USA: Highest high and lowest lows. Mortgage Professional America.

https://www.mpamag.com/us/mortgage-industry/guides/historical-mortgage-rates-in-the-usa-highest-high-and-lowest-

lows/433237

56

Freddie Mac. (2022, April 25). Trends in mortgage refinancing activity. https://www.freddiemac.com/research/insight/20220425-

trends-mortgage-refinancing-activity

32

do not include cash-out refinancing. The bottom of the bar shows the 25th percentile, the top of the bar shows

the 75th percentile, the line in the middle of the bar shows the median (50th percentile) and the whiskers and

dots show points outside this range.

We found that, consistent across MSAs, fewer homeowners in neighborhoods of color applied for refinancing

than their counterparts in white neighborhoods. If the same percentage of homeowners in neighborhoods

of color were applying for refinancing as homeowners in white neighborhoods, approximately 16,000

more households in neighborhoods of color would have applied for refinancing in 2020-2021. About 16,000

homeowners in neighborhoods of color missed the opportunity to lock in low rates for years to come.

During the period of these historically low interest rates, how much did homeowners save through refinancing?

Estimates by different researchers vary, but an analysis by the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation

(Freddie Mac) provides a useful benchmark. According to this analysis, U.S. borrowers who refinanced their

30-year fixed-rate mortgage into another 30-year fixed-rate mortgage on average saved more than $2,800

annually.

57

If the same proportion of homeowners in neighborhoods of color had refinanced, they could have

saved at least a collective $44 million annually.

57

Freddie Mac. (2021, March 5). Refinance trends in 2020. https://www.freddiemac.com/research/insight/20210305-refinance-

trends

Figure 20: Refinance application rates by majority race in neighborhood

by metropolitan area

2020-2021 refinancing

applications divided by existing

mortgages in 2019

Sources: 2019

ACS, 2020-2021

HMDA refinancing

applications

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

33

We now explore one MSA, Albany, for a more granular look at neighborhood racial composition of homeowners

and refinancing.

Examining the Albany MSA, we see an inverse relationship between the percentage of homeowners of color in a

neighborhood and the number of refinancing applications in that neighborhood.

58

We see that borrowers living

in neighborhoods with more homeowners of color were less likely to reap the benefits of refinancing during the

recent period of low interest rates. It is unclear from the data exactly why fewer of these homeowners applied for

refinancing.

58

The problem appears worse in smaller MSAs, which also generally tend to have fewer refinance applications per capita.

Figure 21: Percent of mortgages with refinancing applications 2020-2021 by racial

composition of homeowners in neighborhood

Albany-Schenectady-Troy

2020-2021 refinancing applications divided

by existing mortgages in 2019

Percent POC among homeowners in 2019

Less

than

10

10-20 20-30 30-40 40-50 50-60 60-70 70-80 80-90 90-100

Sources: 2019 ACS,

2020-2021 HMDA

refinancing applications

20

15

10

5

0

Throughout the state, we see that when homeowners from neighborhoods of color did apply for refinancing,

they were denied more often than were homeowners from majority-white neighborhoods. In Syracuse, an

application for refinancing in a neighborhood of color was 97% more likely to be rejected than an application

from a majority-white neighborhood. In a less dramatic example but showing a pervasive pattern, in Buffalo, an

application from a neighborhood of color was 79% more likely to be rejected; in Albany, 83% more likely; and in

Rochester, 64% more likely.

34

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Figure 22: Denial rate by neighborhood race in 2021, predicted at average

loan amount, credit score, DTI, LTV, and income for POC applicants

(refinancing loans)

Table 6: Probability of denial for refinancing loan with the same application characteristics in 2021, by MSA

59

MSA

Predicted

percentage of denial

for POC tract

Predicted percentage

of denial for white

tract

Percentage of

higher probability

to be denied versus

white tract

Albany-Schenectady-Troy 19.1% 10.4% 83%

Buffalo-Cheektowaga-Niagara Falls 29.0% 16.2% 79%

Dutchess County-Putnam County 18.1% 11.9% 52%

Kingston 18.9% 18.9% 0%

Nassau County-Suffolk County 14.0% 11.6% 20%

New York State 16.0% 12.9% 24%

New York-Jersey City-White Plains

60

15.7% 13.2% 19%

Rochester 26.8% 16.4% 64%

Syracuse 30.4% 15.4% 97%

Utica-Rome 10.8% 9.1% 19%

59

The table shows the probability of denial for an application with the average characteristics of a borrower of color in the

indicated MSA (loan amount, credit score, DTI , LTV, and income).

60

This MSA is called the New York-Jersey City-White Plains MSA; however New Jersey loans were excluded from our calculations.

Percent

Sources: 2019 ACS

and 2018-2021 HMDA

for institutions

regulated by CFPB,

HUD, or NCUA

35

61

The table shows the probability of denial for an application with the indicated race and the following characteristics: loan

amount $386,759, credit score 748, DTI 40, LTV 61, and income $151,921.

62

The column “Percentage higher than probability of denial of white applicant” is the difference between the indicated race and

the denial rate for white borrowers, divided by the denial rate for white borrowers.

In addition, borrowers of color were more likely to be rejected when applying for a refinancing loan. Table

7 shows the predicted percentage of applicants denied for refinancing loans with the same applicant

characteristics.

Table 7: Probability of denial for refinancing loan in 2021

with the same applicant characteristics

61, 62

Applicant race Probability of denial

Percentage higher than probability of

denial of white applicant

White 12.1% 0%

Asian 14.7% 21%

Black 14.7% 21%

Latino 14.8% 22%

Multiple races 12.4% 2%

Another race 21.2% 75%

Unavailable 16.7% 37%

All POC 14.7% 21%

36

Bigger than enforcement: New York policy mandate

Historic policy decisions have created an uneven, racially discriminatory playing field that affects New Yorkers’

ability to own homes and create wealth. This systemic discrimination has fostered lasting harm to this day.

Banks have denied communities of color equal access to credit and banking services for generations — making

it harder for people of color to meet lenders’ credit requirements today.

63

At the same time, homeowners in

high-cost areas have seen their assets increase dramatically in value.

64

This has exacerbated, and continues to

exacerbate, the wealth gap.

This report shows the depth and breadth of the problem, which is far more severe than individual acts of

discrimination. Generations of racially discriminatory policies cannot be remediated simply by enforcing the

fair lending laws, even if we had the resources to do so in a manner that eradicated discriminatory lending

going forward. The harm caused by redlining nearly 100 years ago continues to be felt today through large and

persistent wealth gaps. Moreover, those wealth gaps will continue to compound over time unless we take bold

action.

When redlining made it impossible for a Black man in 1935 to get the loan his white counterpart could get, it

set into motion an intergenerational machine of inequality. His great-grandchildren are far less likely than his

white counterpart’s great-grandchildren to have the same credit history or the money to buy a home today.

When deeds in Rochester routinely included clauses that excluded people of color, they shut Black families out

of the communities that welcomed white families. Black families were denied the opportunity to build wealth in

the communities in which white families were building wealth. That denial lives on today in the lack of financial

foundation that so many Black, Latino, and Asian families experience.

In addition, historically marginalized communities have suffered from a historical and ongoing lack of lending

infrastructure from mainstream financial services companies. Wealthier, and whiter, communities have enjoyed

easy access to many banking options. This disparity has created, and continues to create, a lack of information

about lending options and the lending process — both for individuals and for entire communities.

63

Reynolds, L., Perry, V., & Choi, H. (2021, October 13). Closing the homeownership gap will require rooting systemic racism out of

mortgage underwriting. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/closing-homeownership-gap-will-require-rooting-

systemic-racism-out-mortgage-underwriting

Mortgage underwriting may also deny credit to borrowers who would qualify if a more comprehensive look at their credit history

(such as their rental payment history) was used to illustrate their financial responsibility and qualifications.

64