This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau

of Economic Research

Volume Title: Advances in the Economics of Aging

Volume Author/Editor: David A. Wise, editor

Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Volume ISBN: 0-226-90302-8

Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/wise96-1

Conference Date: May 6-9, 1993

Publication Date: January 1996

Chapter Title: Health Insurance and Early Retirement: Evidence from the

Availability of Continuation Coverage

Chapter Author: Jonathan Gruber, Brigitte C. Madrian

Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c7320

Chapter pages in book: (p. 115 - 146)

4

Health Insurance and Early

Retirement: Evidence from the

Availability of Continuation

Coverage

Jonathan Gruber and Brigitte

C.

Madrian

The dramatic postwar decline in the labor force participation of older men in

the United States has motivated a sizable body of literature on retirement be-

havior. Three factors, in particular, have been studied extensively: the growth

of the Social Security program (see, for example, Burtless 1986; Burtless

and Moffitt 1984; Diamond and Hausman 1984; Hausman and Wise 1985;

Sueyoshi 1989), the increased availability and generosity

of

private pensions

(Stock and Wise 1990a, 1990b), and the expansion of federal disability insur-

ance (Bound and Waidmann 1992). One potentially important factor that until

recently has not received much attention is the availability of health insurance

for retirees. This oversight is especially surprising given the rather consistent

evidence that health status is an important determinant in the retirement deci-

sion (Bazzoli 1985; Diamond and Hausman 1984). If health status matters in

the decision about when to retire, it seems quite natural that health insurance

should matter as well.

The increased availability

of

health insurance for older Americans, espe-

cially retirees, has come in several forms. First among them is the introduction

in the mid- 1960s of Medicare, a federal program that provides near-universal

health insurance coverage for those over age 65. A second source of health

insurance that has grown in importance, particularly for those under age 65

who are not yet eligible for Medicare, is employer-provided postretirement

health insurance. While only

30%

of men who retired in the early 1960s re-

Jonathan Gruber is associate professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technol-

ogy and a faculty research fellow of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Brigitte C. Ma-

drian is assistant professor of economics at the University of Chicago and a faculty research fellow

of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The authors wish to thank David Cutler, James Poterba, Andrew Samwick, Richard Zeckhauser,

and seminar participants at

Hanard,

MlT,

and the NBER for their comments, and Aaron Yelowitz

for his help

in

assembling the

SIPP

data.

They also acknowledge financial support from the James

Phillips Fund, the

Harry

and Lynde Bradley Foundation, and the National Institute on Aging.

115

116

Jonathan

Gruber

and Brigitte

C.

Madrian

ceived health insurance from their former employers,

this

fraction increased to

almost half for those retiring in the 1980s (Madrian 1994).

This paper looks at the effect on retirement of a third source of health insur-

ance for early retirees, namely continuation coverage benefits. During the late

1970s and early 1980s many states mandated that employers allow employees

who leave their jobs to continue purchasing their group health insurance for a

specified number of months. These continuation benefits were extended to all

workers in 1986 as part of the federal Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconcil-

iation Act (COBRA) legislation. Although this coverage is available to all

workers regardless of age, it should be particularly attractive to older workers

who face a relatively high price for health insurance in the private market and

who are more likely to be subject to the preexisting-conditions exclusions that

are characteristic of such policies.

To

identify the effect of continuation benefits on retirement, we exploit the

fact that these benefits were mandated at different times by different states

(and finally the federal government) and that the generosity of the mandates

varied across states as well. Using data from the Current Population Survey

(CPS), we find a strong correlation between the availability of continuation

benefits and the likelihood that individuals are retired. Our key finding is that,

among men aged

55-64,

one year of continuation benefits increases the proba-

bility

of

being retired by

1

percentage point; this is

5.4%

of the baseline proba-

bility of being retired for

this

group. Furthermore, we find that, although the

estimated percentage-point effects are strongest near the age of Medicare eligi-

bility, as a fraction of baseline retirement probabilities they actually decline

with age. Although this latter result is somewhat counterintuitive, it is consis-

tent with other work that examines the effect of continuation coverage on flows

into retirement (Gruber and Madrian 1995). We also find that continuation

coverage mandates significantly increase the likelihood that early retirees are

covered by employer-provided health insurance after retirement. This effect is

much larger than the implied effect on retirement, suggesting that much of the

increase in coverage is occumng among those individuals who would have

retired even in the absence of such benefits.

The organization of the paper is as follows. Section 4.1 provides some moti-

vation for why health insurance should matter in the early retirement decision.

Section 4.2 outlines the state and federal continuation coverage laws, which

we use to identify the effect of health insurance on retirement. This is followed

in section

4.3

by a model that formalizes the effect of health insurance

on

retirement. The data and regression framework are presented in section 4.4,

and the results follow in section 4.5 along with a comparison with our findings

from dynamic models of retirement behavior. Section 4.6 considers the impact

of continuation coverage mandates on insurance coverage. The paper con-

cludes in section 4.7 with a discussion of the methodological and policy impli-

cations of our results.

117

Health Insurance and Retirement

4.1

Health Insurance and Retirement: Should It Matter?

The high and variable level of medical expenditures for persons aged 55-64,

without the guarantee of public coverage through Medicare for those over age

65,

means that the availability of health insurance coverage could be a key

factor in determining the timing of retirement. Until recently, however, there

has been little study of the effect of retiree health insurance coverage

on

retire-

ment patterns. Two recent papers have attempted to model the role of health

insurance

in

the retirement decision. Lumsdaine, Stock, and Wise (1994) in-

corporate the value of Medicare into an option value model of retirement and

find

no

effect of Medicare eligibility

on

the retirement hazard. Their result is

not surprising, however, as they estimate their model

on

a sample of workers

from the same firm, all of whom have employer-provided postretirement health

insurance that is much more generous than Medicare. Gustman and Steinmeier

(1994) use information from the Retirement History Survey, a longitudinal sur-

vey from the 1970s, to ascertain whether individuals have employer-provided

retiree health insurance, and data from the 1977 National Medical Care Expen-

diture Survey, to impute the value of that insurance based

on

individual charac-

teristics. They also find very small effects of retiree health insurance

on

retire-

ment decisions.

The results of these two studies are at odds with

both

intuition and with what

individuals report about the importance of health insurance in the retirement

decision.

In

a recent Gallup poll, 63% of working Americans reported that they

“would delay retirement until becoming eligible for Medicare [age 651 if their

employers were not going to provide health coverage” despite the fact that

50%

“said they would prefer to retire early-by age 62” (Employee Benefits

Research Institute 1990). The apparent contradiction between the importance

of health insurance as stated by individuals and that estimated by these two

previous studies provides a further motivation for our research.

4.1.1

Health Status of Older Individuals

That individuals should cite health insurance as an important consideration

in the retirement decision is not surprising, as older persons are fairly likely

to need expensive medical care. Tables 4.1-4.4 compare the health status of

individuals by age along a number of dimensions. The simplest measure, self-

reported health status, is shown in table 4.1. The fraction of individuals who

report being in fair

or poor

health increases markedly from ages

45-54

(19.7%) to ages 55-64 (31.3%). While recent research has suggested that self-

reported health status may be a poor indicator of the actual severity of an indi-

vidual’s clinical conditions (Bazzoli 1985), it may be the most accurate mea-

sure of an individual’s valuation of health insurance coverage. Thus, these fig-

ures suggest that insurance valuation will rise dramatically with age.

Furthermore, as table 4.2 shows, health status as measured by doctor-

118

Jonathan

Gruber

and Brigitte

C.

Madrian

Table

4.1

Self-Reported Health

Status

by Age

(%)

Health Status

Age Excellent

Good

Fair

Poor

25-34 36.4 53.1

9.5

1.1

35-44 32.0

54.6

11.9 1.5

45-54 27.8

52.5 15.6 4.1

55-64

18.0 50.7

24.9 6.4

65

+

9.3 43.1

36.1 11.4

Source:

Authors’ calculations using data from the

1987

National Medical Expenditure Survey.

Note:

The numbers in the table give the fraction

of

individuals who report having the given

health status.

Table

4.2

Incidence of Health Problems by Age

(%)

Condition

25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65

+

Stroke

Cancer

Heart attack

Gallbladder disease

High blood pressure

Arteriosclerosis

Rheumatism

Emphysema

Arthritis

Diabetes

Heart disease

Any

of

the above

0.4

1.6

0.3

1.6

10.1

0.2

0.8

0.4

5.1

1.7

0.8

18.2

0.8

2.4

1.1

3.6

18.2

0.6

1.6

1

.o

11.6

3.0

2.2

31.7

1.6

4.7

3.8

7.3

29.1

2.8

5.2

2.6

24.9

5.7

6.1

51.8

3.6

9.7

7.7

9.4

41.9

6.1

8.2

5.2

41.2

9.8

11.9

72.3

7.4

13.3

13.3

14.6

49.8

16.3

16.4

8.0

54.9

14.7

22.2

84.2

Source:

Authors’ calculations using data from the

1987

National Medical Expenditure Survey.

Nure:

The numbers in the table give the fraction

of

individuals who report ever having had the

listed medical condition.

diagnosed health problems deteriorates with age as well. The incidence

of

many

of

the health problems listed (stroke, cancer, heart attack, arteriosclero-

sis, emphysema, and heart disease) more than doubles between

45-54

and ages

55-64.

Furthermore, almost three-quarters

of

those aged

55-64

have been di-

agnosed with at least one

of

the eleven conditions listed. Not surprisingly, rela-

tive to those aged

45-54,

individuals

55-64

are more likely to be admitted to

the hospital over the course

of

a year and spend more time there once admitted

(table

4.3).

The most direct evidence that health insurance should be valued relatively

highly by older workers, however, is that the actual medical expenses incurred

by those aged

55-64

are much higher than those

of

younger individuals (table

4.4).

In every category not only do expenditures rise with age, but the variance

119

Health Insurance and Retirement

Table

4.3

Annual Medical Care Utilization by Age

25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+

Fraction admitted to hospital

(%)

9.2 6.8 8.7

11.0

20.1

Number of admissions (if ever

Nights in hospital (if ever

admitted)

1.17 1.24 1.39 1.5

1.5

admitted)

5.5

6.8 9.3 11.8 13.8

(%)

52.9 55.6 61.1 71.1 81.9

(if any prescribed medicines)

5.2 6.6 11.5 14.7

18.5

Fraction

who

visited a doctor

(%)

64.1 67.1 71.1 77.9

85.8

visited a doctor)

4.6 4.6 5.5 6.0 7.4

Fraction with prescribed medicines

Number of prescribed medicines

Number of doctor visits (if

Source:

Authors’ calculations using data from the

1987

National Medical Expenditure Survey.

Table

4.4

Average Annual Medical Expenditures by Age

(1990

dollars)

25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 75+

Average expenditures

Hospitdinpatient

Physiciadoutpatient

Prescription medication

Total

Average expenditure if

HospitaYinpatient

Physicidoutpatient

Prescription medication

expenditure

>

0

Total

Source:

Authors’ calculations using

data

from the

1980

National Medical Care Utilization and

Expenditure Survey (inflated to

1990

dollars using the Medical Care Component of the consumer

price index).

Note:

Standard deviation

of

expenditures is in parentheses.

120

Jonathan

Gruber

and Brigitte

C.

Madrian

increases as well.

In

1990

dollars, total medical expenditures of those 55-64

averaged

$2,144.

This

represents 5.4% of average total family income for this

age group, 6.9% of average total family income for retired individuals, and

30%

of the average pension income of early retirees.'

A

one-standard-deviation

increase in expenditures for a 55-64-year-old would represent an additional

16.5% of family income. Total

family

medical expenditures would naturally

constitute a much higher fraction of income. Thus, it is easy to see why older

individuals should be concerned about their health insurance coverage after

retirement.

4.1.2 Health Insurance Coverage and Costs

Given the costs of health care for older workers, it should not be surprising

that older individuals are no more likely to be uninsured than their younger

counterparts, as is shown in table 4.5. The sources of health insurance cover-

age, however, differ with age. Even though employment-based health insur-

ance is the predominant source of coverage regardless of age, older individuals

are less likely than younger persons to have employment-based health insur-

ance and much more likely to be covered by a nongroup (individual) or other

group policy. This suggests that individuals who retire early but who do not

have access to employer-provided health insurance turn to the individual mar-

ket for insurance.

The bottom two panels of table 4.5 break down the sources of health insur-

ance coverage by employment status. There are three major differences be-

tween the sources of health insurance coverage for those who are and are not

employed. First, one-fifth of nonworking older persons are insured through

Medicare or Medicaid, while only

1

%

of the older employed receive coverage

from one of these two sources. Second, older nonworking individuals are 40%

less likely to be uninsured than their younger counterparts. Third, relative to

the young, the older nonworking are six times more likely to be covered by

employer-provided health insurance in their own name.

These last two differences are explained in large part by the availability of

employer-provided postretirement health insurance. Forty-five percent of indi-

viduals work in firms that provide retiree health insurance benefits.* The older

nonworking, who are more likely to be retired than the young nonworking, are

therefore more likely to be covered by employer-provided retiree health in-

surance.

There are, nevertheless, a substantial number of older individuals who are

not covered by either employer or government-provided health insurance. It is

these individuals who find themselves in the market for individual health insur-

ance and who we would therefore expect to benefit from the availability of

1.

Exoenditures as a fraction of income are calculated using income data from the March

1990

-

CPS

.

2.

See Madrian

(1994)

for background

on

the structure

and

availability of postretirement

health insurance.

121

Health Insurance and Retirement

Table

4.5

Insurance Coverage by Age

and

Employment Status

(%)

Employment-

Based

Other CHAMPUS/ Medicare/

Any Own Name Group Nongroup CHAMPVA Medicaid Uninsured

~~~~

All individuals

25-54 71.6 51.1 1.2 5.9 5.7 5.6 15.4

55-64 64.5 44.8 4.1 14.5 7.7 10.4 12.0

25-54 78.5 62.7

1.1

5.8 4.9 1.2 13.5

55-64 76.3 63.1 4.0 12.6 6.8 0.8 10.1

25-54 44.2 4.2 1.3 6.2 8.8 23.4 23.0

55-64 51.6 24.7 4.3 16.6 9.2 20.9 14.1

Source:

Authors’ calculations using data from the

1987

National Medical Expenditure Survey.

Employed

Not employed

continuation coverage. The reason is simple-insurance in the individual mar-

ket is typically quite expensive.

Employers have significant cost advantages in providing health insurance.

By pooling the risks of many individuals, they are able to lower administrative

expenses and reduce adverse selection. These two factors alone are estimated

to reduce the cost

of

providing insurance in large (ten thousand or more em-

ployees) firms relative to small (one to four employees) firms by 40%

(Con-

gressional Research Service 1988). For older individuals the cost differential

between employer-provided and individual health insurance is exacerbated be-

cause policies in the individual market are typically age-rated, while within

the

firm

younger workers subsidize the health insurance costs of their older

coworkers. The Congressional Research Service (1988) reports that the cost to

employers of providing insurance coverage for 55-64-year-old males is three

times that of providing coverage to males under 40; for females, the ratio is

two to 0ne.3

In Massachusetts the average cost of family health insurance coverage per

employee in 1989 was $3,882.4 When inflated by the medical care component

of the consumer price index, this is equivalent to

$5,047

in 1993 dollars.

In

contrast, a New England commercial insurance company is offering a family

policy for a 58-year-old male with

a

one-year preexisting-conditions exclusion

at a price of $8,640. This represents 26% of the average family income of

retired individuals aged 55-64 in Massachusetts. Individual policies may also

be medically underwritten

so

that sick individuals may face substantially

higher prices or may not be able to purchase a policy at all.

3.

Of course, to the extent employer costs can be shifted to the wages of employees in

an

age-

4.

Authors’ calculation using unpublished data from the Health Insurance Association

of

specific fashion, older individuals will bear these higher costs. See the discussion in section

4.3.

America.

122

Jonathan

Gruber

and

Brigitte C.

Madrian

The coverage available in the private market not only is expensive, but also

is typically less generous than employer-provided health insurance. Table

4.6

compares the health insurance benefits of individuals covered under group and

nongroup policies in

1977.

In every category, those covered under nongroup

policies receive more limited benefits. Relative to those with nongroup cover-

age, those with group policies are more than twice as likely to receive major

medical coverage or coverage for physician office visits and prescription drugs,

and more than

50%

more likely to receive ambulance, mental health, and out-

patient diagnostic service coverage. Furthermore, nongroup policies generally

feature both higher deductibles and higher copayments. Thus, relative to the

individual market, group coverage offers individuals higher-quality insurance

coverage at a significantly lower price.

4.2

Continuation Coverage Laws

For those individuals whose employers do not offer retiree health insurance,

an alternative to purchasing health insurance in the individual market is pro-

vided by various state and federal continuation coverage laws. These laws man-

date that employers sponsoring group health insurance plans offer terminating

employees and their families the right to continue their health insurance cover-

age through the employer’s plan for a specified period of time. The laws gener-

Table

4.6

Group

and

Nongroup Health

Insurance

Benefits,

1977

(%)

Fraction

of

Individuals

with

Specified Benefit

Group Plans Nongroup Plans

Primary benefits

Major medical coverage

86.9 39.1

Hospital room and board 98.4 91.4

Surgery

97.6 91.6

Physician office visit

87.9 40.4

Ambulance

89.0 54.0

Outpatient diagnostic services 95.9 66.0

hescribed medicines

87.3 30.3

Mental health

92.2 66.0

Other benefits

Generosity

of

benefits (conditional on

having benefit)

Major medical deductible

<

$100 94.3 61.6

Full semiprivate room charge 77.8 38.2

80-100%

of

usual common

and

reasonable surgical charge 70.6 60.0

80-100%

of

usual common

and

reasonable physician charge 91.8 81.3

Source:

Farley (1986), tables

45-58.

123

Health Insurance and Retirement

ally apply to all separations (except those due to an employee’s gross miscon-

duct), although in some states benefits are restricted to those who leave their

jobs in~oluntarily.~ They often also provide benefits to divorced or widowed

spouses and their families. The first such law was implemented by Minnesota

in 1974. More than twenty states passed similar laws over the next decade

before the federal government, as part of the 1985 COBRA, mandated such

coverage at the national level. Continuation coverage is now commonly re-

ferred to as COBRA coverage, a nomenclature we will also use.

The various state statutes are summarized in table 4.7.6 The length of cover-

age is generally quite short, from three to six months, although nine states

mandate coverage of nine months or more. Although most state laws stipulate

that an employee must have been covered by an employer’s insurance for three

to six months before being eligible for continuation coverage, this requirement

is not likely to be binding on older workers, most of whom have been with

their current employer for many years.’ The state laws also apply only to firms

that actually purchase insurance through an insurance company; self-insured

firms, under the 1974 Employee Retirement Income and Security Act

(ERISA), are not subject to these (or any other) state mandates.*

Although similar in spirit, the state and federal laws differ in a number of

important ways. First, the length of coverage mandated under the federal law,

eighteen months, equals or exceeds that mandated by all but one state (as of

January 1987, Connecticut law provides for up to twenty months of c~verage).~

Second, there is no minimal length of time for which an employee must be

covered under an employer’s plan before being eligible for continuation bene-

fits. Third, the federal law applies to self-insured firms, who are exempt from

the state laws, as well as to those who purchase their coverage from insurers.

The federal law, however, does not apply to small firms employing less than

twenty workers. Finally, employees of religious organizations and the federal

government were exempt from COBRA, although federal employees have sub-

sequently been included (beginning in 1990). When the specific details of the

5. Because retirement is a voluntary separation, we treat those states whose laws apply only to

involuntarily terminated employees as states without laws.

6.

Details on state laws are from Hewitt (1985) and Thompson Publishing Group (1992) and

have been cross-checked against the actual state statutes. Table

4.7

lists only those states with laws

that apply to employees who terminate their employment voluntarily.

7.

Almost 95%

of

retirees have job tenure of at least ten years by the time they retire (Madrian

1994).

8.

In a related paper we incorporate a correction factor that accounts for the exclusion of some

firms

from the effects of these laws

(Gruber

and Madrian 1995). This has little effect on the sig-

nificance of the estimates

of

the effect of continuation coverage on retirement, although the magni-

tude increases two- to threefold.

9. Eighteen months is the maximum length of coverage available following the voluntary

or

involuntary termination of employment. COBRA

also

provides up to thirty-six months of coverage

for family members who would otherwise lose their insurance coverage through events such as an

employee’s death, divorce

from the employee,

or

the employee’s eligibility for Medicare.

124

Jonathan

Gruber

and Brigitte

C.

Madrian

Table

4.7

State

Continuation Coverage

Laws

Effective Months of Effective Months

of

State Date Coverage State Date Coverage

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Georgia

Illinois

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Minnesota

Missouri

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Mexico

7/20/79

1/1/85

7/1/86

10/1/75

1/1/87

7/1/86

1/1/84

8/23/85

7/1/87

1/1/78

7/15/80

81 1 174

3/19/83

6/1/87

9/28/85

1/1/88

8/22/8 1

7/1/83

4

3

3

10

20

3

6

9

9

6

9

6

12

18

9

18

10

6

New

York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Oklahoma

Oregon

mode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Wisconsin

1/1/86

1/1/82

7/1/83

1/1/76

1/1/82

1/1/88

1/1/79

1/1/90

7/1/84

3/3/88

1/1/81

1/1/81

7/1/86

5/14/86

4/17/86

5/14/80

6

3

10

1

6

18

2

6

3

18

3

6

2

6

3

18

Sources:

Hewitt

(1985);

Thompson F’ublishing Group

(1992);

state statutes.

state and federal statutes are at odds, firm provision of continuation benefits is

governed by the law that provides for more generous coverage.

The effective dates of the state laws are listed in table 4.7. The federal cover-

age mandated under COBRA was phased in. Beginning in July 1986, firms

had to offer continuation benefits at the

start

of their next plan year. For work-

ers provided health insurance under union contracts, such benefits did not have

to be offered until the next contract negotiation after January 1987.

Both the state and federal laws stipulate that the employee must pay the full

cost of the coverage. At the federal level,

this

is defined specifically as 102%

of the average employer cost of providing coverage. The coverage must be

identical

to

that provided to similarly situated active employees, including the

option to continue enrollment in supplemental insurance plans (such as for

vision or dental care) if these are available. Although 102%

of

the employer’s

cost is typically much more than individuals pay as active employees, it

is,

as

already noted, substantially less than the cost of buying equivalent coverage in

the private market, especially for older workers.

Because continuation coverage is a relatively new phenomenon (at least at

the national level), information on the extent of continuation coverage is some-

what scarce. Zedlewski (1993) estimates that, in 1988,5.2% of retired workers

aged 55-64 were covered by COBRA health insurance. This figure must be

interpreted relative to the number of individuals who could be expected to

take up such coverage. The 52% of individuals aged 55-64 with retiree health

insurance are not likely to be covered, and the 21% of individuals who were

125

Health Insurance and Retirement

not insured through their former employer are not eligible. Similarly, those

who have been retired for more than eighteen months have exceeded their po-

tential eligibility. Tabulations from the 1987 National Medical Expenditure

Survey indicate that one-third of retired individuals aged

55-64

have been re-

tired for less than eighteen months. If we take the group who could potentially

be affected by COBRA to be one-third of retired individuals between ages

55

and

64

who worked in firms that provided health insurance but did not provide

retiree health insurance, we would expect at most 9% of early retirees to be

covered. That 5.2% receive continuation benefits suggests that

58%

of

the re-

tired population who would be at all likely to be covered by COBRA actually

are. As knowledge about the availability of such coverage has become more

widespread since 1988, this fraction may be higher today.

An alternative calculation is possible using figures reported in Flynn (1992).

She uses data from a large firm that administers COBRA claims to estimate

that 23% of individuals who qualified for COBRA coverage because of retire-

ment elected to receive benefits. If we expected only the

30%

of individuals in

firms that offer health insurance but do not offer retiree health insurance to

even consider purchasing COBRA insurance,

this

take-up rate implies that

75%

of those most likely to be covered by continuation benefits actually are.

Both of these calculations, therefore, suggest that retirees without an altema-

tive source of health insurance coverage are quite likely to elect continuation

coverage.

For all COBRA beneficiaries, the average length of time

on

COBRA was

seven months (Flynn 1992). Individuals over age

61,

however, maintained their

coverage for a much longer period of time-about twelve months on average.

This finding is not surprising for two reasons. First, younger individuals are

more likely to find alternative coverage through a new job or a spouse’s em-

ployment. Second, COBRA coverage provides a larger subsidy for older work-

ers; with a lower relative price, they should therefore demand more coverage.

Table 4.8 compares the distribution of health insurance coverage in 1984,

two years before COBRA was first implemented, and in 1989, two years after

it had been phased in. Note that employment-based health insurance coverage

is

more prevalent after COBRA, and that

this

effect is confined to those who

are not employed, exactly

the

group whom we would expect to be insured

under COBRA.

This

finding is similar to evidence presented in Rogowski and

Karoly (1 992), who examined the primary source of insurance coverage after

retirement, based

on

the source of insurance coverage before retirement, before

and after COBRA. They find that in the pre-COBRA period,

72%

of individu-

als who retired from jobs with employment-based health insurance continued

to be covered by that insurance upon retirement. After COBRA, this figure

rises to

78.5%.1°

Taken together,

the

evidence

on

take-up rates and the increase

in the extent of employer-provided health insurance coverage among early re-

10.

We

present a stronger test of the effect

of

continuation coverage mandates on insurance

coverage in section

4.6.

126

Jonathan

Gruber

and

Brigitte

C.

Madrian

Table

4.8

Health Insurance Coverage before

and

after

COBRA

(%)

-

~~~~ ~ ~~

All Individuals Employed Not Employed

25-54 55-64 25-54 55-64 25-54 55-64

Insurance coverage in

1984

Any private health insurance

Health insurance in own name

Employ ment-based

Not employment-based

Covered as a dependent

Insurance coverage in

1989

Any private health insurance

Health insurance in own name

Employment-based

Not employment-based

Covered as a dependent

82.1 83.7 89.1 92.5 60.1 74.1

52.1 47.4 66.7

68.9

5.9 23.6

5.1 12.5

5.1

10.4 5.2

14.7

24.2 23.4 16.8

12.8 47.7

35.0

82.4 84.3 88.6 92.1 57.3 74.9

54.7

49.2 66.4

68.1 7.1 26.6

5.3

12.9

5.2

9.6

5.2 16.8

22.0 21.8

16.4

14.4 43.7

30.6

Source:

Authors' calculations using data

from

the Survey

of

Income and Program Participation,

1984

Wave

3

and

1987

Wave

7.

tirees after COBRA suggests that older workers who retire early and who

do

not have an alternative source of coverage actually avail themselves of the con-

tinuation benefits to which they are entitled.

4.3

Modeling the Effect

of

Health Insurance on Retirement

We present a simple graphical exposition of the effect of health insurance

benefits on the retirement decision, along the lines of Burtless (1986) and Burt-

less and Moffitt (1984). We consider both retiree health insurance in general

and continuation benefits more specifically. Figure

4.1

shows

the

budget con-

straint facing an older worker between the ages of

55

and

65.

The horizontal

axis represents

the

age of retirement. The vertical axis measures the certainty

equivalent

(CE)

of consumption from age

55

onward.

This

differs from the

earlier literature, which has typically considered the relationship between the

age at retirement

and

the actual level of future consumption rather than the

CE

of future consumption.

This

departure is necessitated by our focus on the effect

of insurance coverage.

We assume that workers receive health insurance on their current job but

that they may or may not have retiree health insurance coverage. Firms that

provide postretirement health insurance do

so

on the same basis for both work-

ers and retirees, and these benefits cease upon eligibility for Medicare." We

also assume that once workers leave their current job, they will remain retired

for the rest of their life.

To

simplify the analysis, we ignore the effects of both

11.

In reality, most retiree health insurance plans do "top

off"

Medicare to some extent. This

does not alter the main conclusions

of

this section.

127

Health Insurance and Retirement

Cer

to

i

nty

Eq

u

iv

a

I

en t

of

Future

Consumption

65

R3 R4

*o

R*

55

Retirement

Age

Fig.

4.1

Modeling the effect

of

continuation coverage on retirement

Social Security and pensions; they could, however, be easily incorporated into

the analysis.

In the model, as in the real world, workers who retire without health insur-

ance coverage have two options: they may purchase an individual policy, or

go uninsured. In either case their out-of-pocket medical expenditures will be

significantly higher than if they receive retiree coverage or have the option of

continuing their group coverage. For a worker with retiree health insurance,

the slope of the budget constraint will be the after-tax wage, which is depicted

by line

AB

in figure 4.1. Since medical expenditures are insured, there is

no

uncertainty about future consumption.

For the worker without retiree coverage, the relative position and slope of

the budget constraint depend on two factors. First, because individuals are

risk

averse, those without retiree health insurance will have a lower level of

CE

consumption; this places the no-health-insurance budget constraint below that

of an insured worker.'* Second, because both the mean and the variance

of

medical expenditures rise with age, a year of health insurance coverage is

worth more at older ages. The cumulative reduction in

CE

consumption will

be greater at younger retirement ages, but the incremental effect will be

smaller. This latter effect gives curvature to the no-health-insurance budget

constraint, line

CD

in figure 4.1. At age

65

there is a jump

in

the no-health-

insurance budget constraint as Medicare equalizes the opportunities of all indi-

viduals.

If leisure is a normal good, retiree health insurance will lead to earlier retire-

ment, at age

R,

<

R,,

because such coverage makes individuals wealthier. As

12.

Risk aversion

in

this

model

operates in a

similar

fashion

to

higher

expected

medical

costs.

128

Jonathan

Gruber

and Brigitte

C.

Madrian

individuals are more risk averse, the wealth effect will increase as both the

level of the no-health-insurance budget constraint falls and its slope becomes

steeper.

Now consider the effect of a continuation coverage mandate that provides

one year of subsidized insurance coverage relative to having no health insur-

ance. For the risk-neutral worker, this is simply equivalent to an increment in

wealth equal to expected medical costs for a year minus the cost of the group

policy.13 This increment rises in value as the worker ages, since expected medi-

cal expenditures increase with age. Thus, the budget constraint with a continu-

ation coverage option, line

EE

lies above the no-health-insurance constraint

but below the retiree-coverage constraint. At younger ages, it is very close to

the no-health-insurance constraint; at age 64, it differs from

the

retiree-

coverage constraint by the cost of

the

group coverage. As workers become

more risk averse and the no-health-insurance constraint becomes steeper, the

distance between the no-health-insurance and the continuation coverage con-

straints will increase, and

this

increase will be greater at older ages. In this

case the value of one year of coverage will equal expected medical costs minus

the cost of the group policy plus the increase in

CE

consumption implied by

eliminating uncertainty in that year.

The value of both retiree health insurance and continuation benefits will rise

with the cost of being uninsured or the cost of buying individual insurance

in

the

private market. The important difference between these two sources of

coverage, however, is their age patterns: while retiree insurance coverage is

of

highest value to very early retirees, continuation benefits

are

more valuable at

older ages. Because of this, we might expect continuation benefits to be used

primarily by older workers seeking a “bridge to Medicare,” which allows them

to retire a certain number of months before age 65 without losing group cover-

age. If this is the case, we would expect the effect of continuation coverage on

retirement to be greatest at older ages.

There are, however, a number of complications that cloud this basic intu-

ition. The first is the empirical violation of one of our assumptions, namely,

that retirement is permanent. Diamond and Hausman (1984) report substantial

reentry rates for early retirees; among 55-64-year-olds, the one-year reentry

rate is approximately 15%. Sueyoshi (1989) finds that one-third of the elderly

“partially retire,” moving from permanent employment to less than full-time

work.

To

the extent that continuation coverage mandates facilitate movement

across jobs, rather than permanent retirement, they may have larger effects at

younger ages than was depicted above.I4

In this analysis we have assumed that retiree health insurance offers pure

13.

Once again, this amount is presumably positive even for a risk-neutral worker due

to

cross-

14.

One important consideration,

of

course,

is

whether this reentry

is

to jobs that offer health

subsidization

of

the group policy by younger coworkers.

insurance; unfortunately, there

is

little evidence on this question.

129

Health Insurance and Retirement

rents to workers in the firms that offer this type of coverage. In labor market

equilibrium, presumably at least a portion of these rents will be reflected in

lower wages for workers with retiree coverage. The extent to which these com-

pensating differentials offset the benefits of retiree health insurance at each

age will be a function of the employer’s ability to set relative age-specific

wages freely,I5 the mobility of workers across firms at different ages, and the

excess of the cost of continuation benefits over the group premium paid by the

early retiree.I6 The existence of compensating differentials may affect both

the location and the shape of the budget constraint facing the potential retiree;

the net effect on retirement age will

be

a function of the nature of the compen-

sating differential.”

Finally, we have ignored the possibility that workers may be liquidity con-

strained in making their retirement decisions. The fact that most retirees have

few liquid assets (Diamond and Hausman 1984) implies that such liquidity

constraints may

be

empirically important in determining retirement dates. This

explanation is suggested in both Diamond and Hausman (1984) and Burtless

and Moffitt (1984) in their discussion of why Social Security benefits do not

seem to affect retirement until they actually become available at age

62.

Sam-

wick (1993) finds that much of the estimated increase in retirement probabili-

ties attributed to Social Security occurs among those with pensions, suggesting

that all workers would like to take advantage of these benefits early, but that

only those with pensions can afford to do

so.

The presence of liquidity con-

straints could increase the effect of continuation benefits at younger ages, as

the wealth increment that these benefits represent could be loosening these

constraints.

4.4

Data and Regression Framework

4.4.1 Data

The data for

this

study must meet two key criteria. First, in order to exploit

the variation in state and federal continuation coverage legislation, they must

extend over a number of years before and after 1986. Second, there must be a

15. See Rosen (1986) for a discussion

of

the theory of compensating differentials. Gruber

(1994a) provides some evidence that shifting the costs of employer-provided benefits

to

distinct

demographic groups

in

the workplace is feasible.

16. Huth (1991) reports that

the

health insurance claims

of

COBRA

recipients exceed those of

active employees by

50%.

This difference in cost is attributed

to

adverse selection; it is the sickest

individuals who will find continuation coverage most attractive, and they will therefore be the ones

most likely to take it up. Similar evidence is provided in Long and Marquis (1992).

17. For example, if the entire cost of the benefits is shifted to older workers,

this

will lower the

slope of the budget constraint with continuation benefits (fig.

4.1)

relative to the budget constraint

without benefits (because wages for those with benefits fall), which will have both income and

substitution effects on the retirement decision.

130

Jonathan Gruber and Brigitte

C.

Madrian

large sample size

so

that the effects of state-law changes on older workers can

be identified. The data that best meet these two criteria are the Merged Outgo-

ing Rotation Group (MORG) sample of the

CPS.

The

CPS

is a nationally rep-

resentative survey that interviews over fifty thousand households each month.

The MORG file contains information on demographic characteristics and labor

force attachment during the survey week for one-quarter of each month’s

sample for each month of the year. This is the largest available annual data set

on individual labor force behavior in the United States.

Recent studies of retirement behavior have focused on dynamic modeling of

the transition into retirement. In this paper we instead use a static model of

whether or not an individual is currently retired, since the only labor force

information we have in the MORG is for the week of the interview. Evidence

on the stock of retired persons can still be useful for considering the effect of

continuation coverage mandates

on

retirement; if the laws are affecting flows,

they should affect stocks as well.L8 Furthermore, dynamic modeling strategies

for retirement decisions using survey data sets often suffer from an important

econometric difficulty, known as dynamic sample selection bias (Diamond and

Hausman

1984).

In the case of continuation coverage laws, this bias arises

from the fact that the set of individuals observed actually working after the law

has been in place for a number of years would be less likely to retire in re-

sponse to the law than would the entire population, because those most likely

to respond will have already retired. When the sample is selected on the basis

of those who are still working, the results will therefore be biased against

find-

ing an effect of the law.19 In a multivariate setting, the bias cannot be signed

a priori, and with time-varying covariates in the model, such as months of

continuation coverage, it is impossible to correct for this “left-censoring.”20

Our static regressions, which include all 55-64-year-old males regardless of

initial work status, do not suffer from this bias.

On the other hand, the major disadvantage of our static framework is that

we cannot control for the characteristics of

the

job from which the individual

has retired. This will be important if, for example, there is a systematic correla-

tion between the passage of these mandates and the nature of the jobs in the

states where they are passed. In the regression analysis we attempt to reduce

any bias that results from this potential correlation by controlling for the time-

18.

This

is not strictly true if the mandates affect the number

of

persons who decide to work at

all; in this case, both the numerator and denominator of the labor force participation rate would

be increasing, and the effect on

the

stock would be ambiguous.

This

is not likely to be a problem

for the sample of older males on which we focus.

19.

An

alternative way to see

this

point is to imagine a law that applied to a cohort rather than

to

an

age group. The individuals who are most likely to respond to

this

law will do

so

in the

first

year. In the next year, by selecting on the set of individuals who have not yet retired, we will bias

the results against finding an effect of the law. When the law applies to an age group, rather than

a cohort, this effect is attenuated by the fact that new members arrive into the age group.

20.

It

is

possible, however, to test for the magnitude of the bias; see Gruber and Madrian

(1995).

131

Health Insurance and Retirement

invariant characteristics of the states that pass these mandates. In section 4.5

we will contrast our findings from this static regression with those from dy-

namic models that allow us to better control for the types of jobs held by indi-

viduals.

4.4.2 Regression Framework

We focus

on

two definitions of retirement: whether or not an individual re-

ports being retired, and whether or not an individual is out of the labor force.

Both are based on a

CPS

question that asks about the major activity in which

an individual was engaged during the week before the survey. The latter defini-

tion is useful because

retirement

may be a subjective term that takes on differ-

ent meanings for different individuals. These retirement definitions

are

clearly

problematic along at least two dimensions. First, we are unable to contrast the

effect of these regulations on both “full” and “partial” retirement, as is done in

Burtless and Moffitt (1984) or Sueyoshi (1989). Second, we are unable to ac-

count for reentry into the labor market, as discussed in Diamond and Hausman

(1984). Nevertheless, these measures should provide reasonable estimates of

the effect of continuation coverage mandates on the propensity of older work-

ers to remain employed.

Our sample consists of men between the ages of

55

and 64. Overall,

20%

of

the sample report being retired, and

35%

are out of the labor force. The average

level of education is twelve years, and 9.5% of the sample is nonwhite.

We estimate the following probit model of retirement:

(1)

Pr(Retired,,)

=

@(a

+

p,*X,,

+

&*Statej

+

&*Timer

+

p,*Lawjr),

where

i

indexes individuals,

j

indexes states, and

t

indexes time.

Xi,,

is a set of

individual demographic characteristics,

Statej

is a set of state dummies,

Time,

is

a

set of year and month dummies, and

Lawjr

is the number of months of

continuation coverage available in state

j

at time

t?

The state fixed effects

control

for

any time-invariant characteristics

of

a state that may be correlated

with the state’s propensity to pass continuation coverage legislation. We in-

clude a set of year dummies to control for national trends in retirement behav-

ior that may be correlated with the passage of these laws, and month dummies

to control for seasonal patterns in retirement behavior. Thus, the effect of the

laws is identified in this model by changes in retirement behavior in states that

passed the laws (or that were affected by the federal law), relative to those

that did not, during the period after the laws were passed. Further identifying

variation comes from differences across states in the number of months of

21.

We

exclude individuals from two

states

from

our

sample: Hawaii, which has mandated

health insurance for

all

employees, and West Virginia,

for

which we were unable to definitively

date

the effective date of their continuation coverage mandate.

132

Jonathan

Gruber

and Brigitte C. Madrian

eligibility that these laws allow. Since we have monthly data, we phase in the

federal law in twelve equal increments between July 1986 and June 1987.

4.5

Results

The basic regression results are reported in table 4.9. The first column re-

ports the probit coefficients

from

the self-reported retirement equation, while

the second column gives the marginal probabilities implied by these coeffi-

Table

4.9

The Effect

of

Continuation Coverage on the Probability

of

Being Retired

Definition

of

Retired

Report Being Retired Not in the Labor Force

Marginal

Independent Variable Coefficient

Probability

Months

of

coverage

0.0036 ,0107

Married

-

0.0

154

-

.0037

Education

-0.0655

-.0162

(.0017)

(.0010)

(.0092)

(.0121)

(.0503)

(.0502)

(.0501)

(.0499)

(0498)

(.0496)

(.0496)

(.0494)

Nonwhite

-0.1204

-

,0282

55

years old

-

1.205

-.1950

56

years old

-

1.097 -.1853

57

years old

-1.016 -.I770

58

years old

-

0.925

1

-.1669

59

years old

-0.8115

-.1525

60

years old

-0.6254 -.1254

61

years old

-0.4903 -.lo24

62

years old

-0.0854

-

,0203

63

years old

0.1033 ,0260

64

years old

0.1938 .0504

(.0494)

(.0494)

Marginal

Coefficient Probability

0.0025

(.0015)

(.0009)

-0.3427

(.0081)

0.0918

(.0104)

0.1180

(.0443)

0.1935

(.0443)

0.2435

(.0443)

0.3157

(.0442)

0.4094

(.0442)

0.5302

(.MI)

0.6394

(.0442)

0.9977

(.0441)

1.161

(.0442)

1.262

(.0442)

-0.0577

.0098

-.0187

-.1173

,0305

,0392

,0646

,0816

,1063

,1385

,1804

,2187

,3441

,3996

,4324

Notes:

The table gives estimates from a probit equation

for

whether

or

not an individual is retired,

using data from the

1980-90

Merged Outgoing Rotation Groups of the Current Population Survey.

The sample comprises

214,508

men aged

55-64.

Coefficients for year, month, and state dummies

are not reported. Standard

errors

are in parentheses.

133

Health Insurance and Retirement

cientsZ2 The same is done in the third and fourth columns, using “not in the

labor force” as the definition of retirement. More education is associated with

a slightly lower probability of being retired and a much lower probability of

being out of the labor force. Being nonwhite is associated with a lower proba-

bility of retirement but a significantly higher probability of being out of the

labor force. Individuals who are married are less likely to be either retired or

out of the labor force. The age pattern of retirement propensities is familiar

from the previous literature; there is a large jump in the probability of being

retired at age

62,

and individuals aged 64 are

25%

more likely to be retired

than individuals aged

55.

This pattern is even more pronounced for being out

of the labor force, as the probability at age

64

is 40% greater than the probabil-

ity at age

55.

The availability of continuation coverage has a sizable and significant effect

on the probability of being retired. One year of coverage raises the probability

that an individual is retired by

1.1

percentage points, which is 5.4% of the

baseline probability of being retired in this sample. For the not-in-the-labor-

force regressions, the estimated effect of a year of continuation coverage is of

approximately the same magnitude as in the retired equation (although the

coefficient is only significant at the

10%

level), and suggests an increase in the

baseline probability of being out of the labor force of

2.8%.

The model described in section 4.3 suggests the possibility that the effect of

continuation coverage mandates on retirement could vary with age; intuitively,

it seemed that this effect should be strongest at older ages. In table 4.10, there-

fore, we free up the effect of months of continuation coverage by age. The

second and fifth columns present the marginal probability derivatives of the

probits. The third and sixth columns express these percentage-point increases

in retirement propensities as a fraction of the baseline retirement rate at each

age. This allows for a more natural interpretation of the percentage effects of

continuation benefits

on

retirement at each age.

In both equations the coefficients rise with age and are statistically signifi-

cant at ages

62

and above. The pattern of effects as a fraction of baseline retire-

ment probabilities, however, is not uniformly supportive of the hypothesis sug-

gested in section 4.3. For the retirement equation, there is actually a declining

pattern

of

effects by age; for the not-in-the-labor-force equation, the effects

are slightly increasing with age.

There are several possible explanations for this counterintuitive finding that

the effects are not proportionately greatest at the ages near Medicare eligibility.

22.

For dummy variables, the marginal probabilities are calculated by predicting the probability

of retirement with the dummy equal to one for the entire sample, predicting the probability with

the dummy set equal

to

zero for the entire sample, and taking the average

of

the difference in these

predictions across all individuals. For continuous variables, the marginal probability is calculated

by predicting the probability at the current level of the variable, predicting the probability by

adding one to the variable, and once again taking the average of the difference in these predictions

across individuals. The marginal probability on months of coverage is the probability increase

associated with going from zero to twelve months of coverage.

134

Jonathan

Gruber

and

Brigitte

C. Madrian

Table

4.10

The Age-Specific Effect

of

Continuation Coverage on the Probability

of

Being Retired

~ ~~

Definition of Retired

Report Being Retired

Not in the Labor Force

Marginal Percentage Marginal Percentage

Independent Variable Coefficient Probability of Baseline Coefficient Probability of Baseline

55*months ,0028 ,0083 13.3 .0012 0047 2.4

(.0023) (.0019)

56*months .0013 ,0037 4.8 ,0022 ,0088 4.1

(.0023) (.0019)

57'months ,002

1

.0061 6.8

-.0005

-.0021 0.9

(.0022) (0019)

%*months ,0027

,0080

7.6 .003

1

1.2

(.0022) (.0019)

59*months ,0046

.O

135 10.6 ,0019 .0074 2.6

(.002

1)

(.0019)

60*months .0024 ,007

1

4.2 .0018 ,0069 2.1

(.0021) (.0018)

6

1

*months ,0020 .0060 2.9

,002

1 ,0085 2.3

(.0020) (.0018)

62*months .0048 ,0143 4.2

,0040

,0161 3.2

(.0020) (.0018)

63*months

,0041

.0121 2.9 ,0045

.O

179 3.2

(.0020)

(.0018)

64*months ,0067 ,0202 4.5 .0063 ,025

1

4.1

(.0020) (.0018)

Notes:

The table gives estimates from a probit equation for whether

an

individual

is

retired, using data

from the 1980-90 Merged Outgoing Rotation Groups of the Current Population Survey. The sample com-

prises 214,508 men aged 55-64. Coefficients for year, month, age, and state dummies are not reported.

Education, race, and

marital

status are

also

included. Standard errors are in parentheses.

The first is the set

of

theoretical issues we raised in section

4.3,

such as the

possibility that individuals may face liquidity constraints that are loosened by

this temporary health insurance. The second reason is statistical: we may not

have enough power to these probits to distinguish true larger effects at older

ages from the effects at younger ages. Given the precision of our estimates, this

seems an unlikely explanation for the unexpected age pattern

of

our results.

Alternatively, it may be that our result is spurious. One potential problem

with our identification strategy is that the passage of these laws could be corre-

lated with some other change

in

retirement behavior in these states. Alterna-

tively, it could be that the laws themselves are endogenous responses to

changes

in

retirement propensities among the population; that is, if more indi-

viduals are retiring, states may respond by mandating benefits that cover indi-

viduals after their retirement.

One form of potential endogeneity could be that the propensity of legisla-

135

Health Insurance and Retirement

tures to mandate continuation coverage is correlated with long-term within-

state trends in retirement behavior. In this case, even with state fixed effects

included in the regression, there will be a spurious correlation between

changes in retirement behavior within a state and the passage of a continuation

coverage mandate. One possible control for such spurious causation is to in-

clude in the regression not only state effects but state-specific trend terms; that

is, we interact each state effect with a trend for the ten-year period.23 The re-

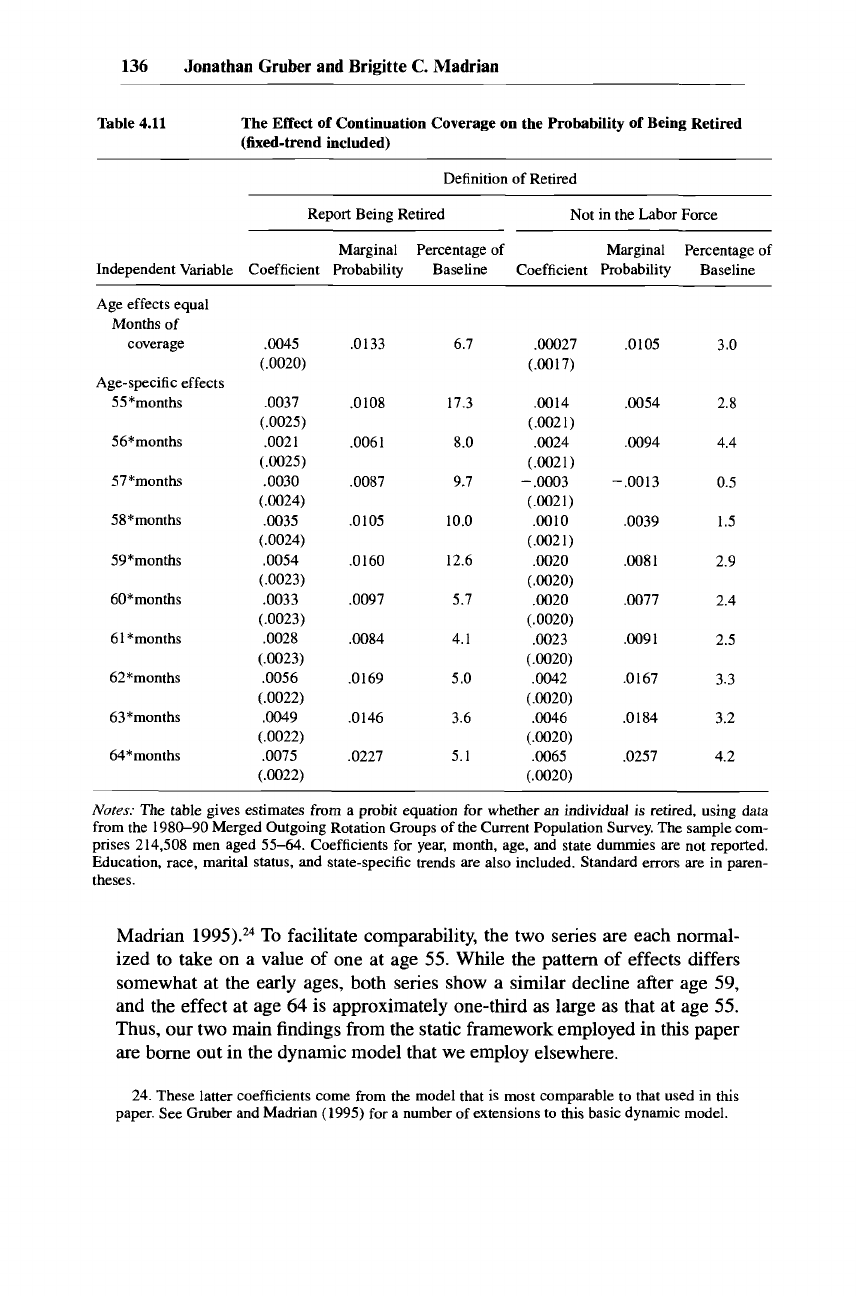

sults from this specification check are presented in table 4.11. For the not-in-

the-labor-force regression, the age-specific coefficients are virtually un-

changed from those in table 4.10; in the retirement equation, the coefficients

are slightly larger, but once again the effects are very similar.

A

further potential problem with these findings is that it may not be appro-

priate to compare the effects of the state and federal mandates.

As

we noted

earlier, these mandates differ along a number of dimensions, the most im-

portant being that the state mandates do not apply to self-insured firms, while

the federal mandate does not apply to small firms. In results not reported, we

have rerun these regressions for the period prior to July 1986 in order to restrict

our analysis to the effects of the state laws. The results are somewhat stronger

than those in tables 4.10 and 4.11, although the age patterns are similar.

In

related work (Gruber and Madrian 1995), we consider the effect of con-

tinuation benefits on transitions into retirement using two different data sets-

the March files of the

CPS,

and the Survey of Income and Program Participa-

tion

(SIPP).

These data sources allow us to estimate dynamic retirement mod-

els and to control for some characteristics of the jobs from which individuals

retire. The sample sizes are much smaller than we have with the MORG data,

however, and we are confronted with the issue of dynamic sample selection,

discussed above. Nevertheless,

this

study confirms the two key findings of the

research reported above. First, there is a sizable and significant effect of contin-

uation coverage on retirement behavior. Using one-year retirement transitions

in the March

CPS,

we find that one year of continuation coverage raises retire-

ment propensities by 1.4 percentage points. This is quite similar to the 1.1

percentage-point effect estimated in this paper using the MORG data. Further-

more, the implied effect on the hazard rate in both the March

CPS

and SIPP

data is identical.

Second, despite the presumption that these laws should act as a “bridge to

Medicare,” the estimated effects in these dynamic models do not rise with age

either. Figure 4.2 graphs the change in the propensity to be retired from having

a year of continuation coverage estimated from the MORG regressions (col-

umn three of table 4.10) along with the percentage increase in retirement prob-

abilities estimated using transition data from the March CPS (Gruber and

23.

The trend

is

monthly, taking on values

of

1

to

132.

This

type

of

“random growth” or “fixed

trend” estimator

is

suggested

by

Heckman and

Hotz

(1988) and is used by Jacobson, LaLonde,

and Sullivan (1992) and Gruber (1994b).

136

Jonathan Gruber and Brigitte

C.

Madrian

Table

4.11

The Effect

of

Continuation Coverage

on

the Probability

of

Being Retired

(fixed-trend included)

~~

Definition of Retired

Report Being Retired Not in the Labor Force

Marginal Percentage of Marginal Percentage of

Independent Variable Coefficient Probability Baseline Coefficient Probability Baseline

Age effects equal

Months

of

coverage

Age-specific effects

55*months

56*months

57*months

58*months

59*months

60*months

6

1

*months

62*months

63 *months

64*months

,0045

(.0020)

.0037

(.0025)

,002

1

(.0025)

.0030

(.0024)

,0035

(.0024)

,0054

(.0023)

.0033

(.0023)

,0028

(.0023)

,0056

(.0022)

,0049

(.0022)

,0075

(.0022)

,0133 6.7

,0108 17.3

,006 1 8.0

,0087 9.7

.0105 10.0

.O

160 12.6

,0097 5.7

,0084 4.1

.O

169 5.0

.O

146 3.6

.0227 5.1

.OOO27

(.0017)

,0014

(.0021)

,0024

(.0021)

-

,0003

(.0021)

.0010

(.0021)

.0020

(.0020)

.0020

(.0020)

.0023

(.0020)

.0042

(.0020)

,0046

(.0020)

,0065

(.0020)

,0105 3.0

.0054 2.8

,0094 4.4

-.0013

0.5

,0039

1.5

,008

1

2.9

,0077 2.4

,009

1

2.5

,0167 3.3

,0184 3.2

.0257 4.2

Notes:

The

table gives estimates

from

a probit equation

for

whether

an

individual is retired, using data

from the 1980-90 Merged Outgoing Rotation Groups of the Current Population Survey.

The

sample com-

prises 214,508 men aged

55-64.

Coefficients for year, month, age, and state dummies are not reported.

Education, race, marital status, and state-specific trends are also included. Standard errors are in paren-

theses.

Madrian

1995).24

To

facilitate comparability, the two series are each normal-

ized to take

on

a value of one at age

55.

While the pattern of effects differs

somewhat at the early ages, both series show a similar decline after age

59,

and the effect at age

64

is approximately one-third as large as that at age

55.

Thus, our two main findings

from

the static framework employed in

this

paper

are borne out in the dynamic model that we employ elsewhere.

24. These latter coefficients come from the model that

is

most comparable

to

that used in this

paper. See

Gruber

and Madrian (1995) for a number of extensions to

this

basic dynamic model.

137

Health Insurance and Retirement

1.6

I

1.4

1.2

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

nl

I

I

I I I

I

I

I

L

1

55

56

57 58 59

60 61 62 63 64

Age

March

CPS

-

_________________

MORG

Fig.

4.2

Relative age-specific effects

of

continuation coverage

on

retirement

It is also interesting to consider what the magnitude of these findings imply

about individual valuation of continuation benefits by comparing them to the

estimated increase in retirement propensities following an increase in postre-

tirement income. The results from a static probit model of retirement in Sam-

wick (1993) suggest that a

$5,000

increment

to

Social Security wealth in-

creases the retirement hazard by approximately

8%.

In a stochastic dynamic

programming model employed by Stock and Wise (1990a, 1990b) and Lums-

daine, Stock, and Wise (1992, 1994), they find that a

$5,000

increase in the

value of pension wealth leads to an increase in the retirement hazard of be-

tween

10

and 13% for individuals between the ages of

55

and

64.25

The

basic specification of Gruber and Madrian (1995) finds that one year

of

continuation coverage raises the retirement hazard by 32%. This implies that a

year

of

continuation benefits is valued at between

$12,300

and

$15,000

in

terms of postretirement wealth. Based on the cost information reported in sec-

tion

4.2,

a COBRA policy would save an older worker approximately

$4,500

per year on the price of family coverage. Taken at face value, these results

suggest that workers value the insurance received from continuation coverage

policies at a somewhat higher level than its associated cost savings. This may

reflect the fact that the individual policy we priced, as with most individual

policies, excluded preexisting conditions for some period. Alternatively, it may

be that a number of early retirees must pay substantially more for individual

policies or are unable to obtain such policies at

all.

25.

We are grateful

to

Andrew Samwick, Robin

Lumsdaine,

and

James Stock for

performing

these calculations

for

us.

138

Jonathan Gruber and Brigitte

C.

Madrian

4.6

Insurance Coverage

In this section we consider the effects of continuation coverage mandates on

the insurance coverage of early retirees. If continuation coverage mandates are

having an effect on the retirement decisions of older workers, then, by defini-

tion, they should be affecting their insurance coverage as well. Thus, evidence

that such mandates increase insurance coverage among early retirees provides

a necessary (but not sufficient) specification check of

our

result that these man-

dates affect retirement behavior. Furthermore, it is interesting to contrast the

direct effects of these mandates on insurance coverage with their indirect ef-

fects

on

retirement behavior.

To

what extent do continuation coverage man-

dates affect the "inframarginal" individual, who would have retired in their

absence, relative to the "marginal" individual whose retirement decision is

made in response to their presence?

In order to investigate the effect of continuation coverage mandates on insur-

ance coverage, we use data from the

SIpP.26

The SIPP is a nationally represen-

tative survey of households designed to collect information on the economic

and demographic characteristics of individuals and their families. We use data

from the

1984,1985,1986,

and

1987

panels of the

SIPP.

Sample members are

interviewed every four months for roughly two and a half years and asked to

provide information about their labor market activity, income, and participa-

tion in welfare and transfer programs over the previous four months. The first

interviews

of

the

1984

panel were conducted in October

1983,

while the initial

interviews for subsequent panels commenced in February of the corresponding

calendar year. For previously cited reasons, we exclude individuals living in

West Virginia and Hawaii. We also drop individuals from several other small

states because, out of concern for confidentiality, the

SIPP

has grouped these

states together, thereby making it impossible to assign the appropriate state

laws to individuals in these states.27

We restrict our sample to men aged

55-64

who retired during the sample

period. The

SIPP

does not ask individuals directly whether they have retired.

We therefore use a measure of retirement based on length

of

time out of the

labor force. This has the advantage, relative to point-in-time self-reported mea-

sures, of capturing transitions to nonwork rather than partial (but perceived)

retirement. It has the disadvantage, however, of not allowing

us

to disentangle

retirement from other reasons for a temporary absence from the labor force.

Following Rogowski and Karoly

(1992),

we define retirement as a departure

26.

To

keep the sample of individuals comparable to the MORG data used in

this

paper, one

could in principle use the March

CPS

to

look

at insurance coverage over

a

similar time period.

Unfortunately, a

1988