Risk Management Examination Manual for Credit Card Activities Chapter XIX

XIX. MERCHANT PROCESSING

Merchant processing is the acceptance, processing, and settlement of payment transactions for

merchants. A bank that contracts with (or acquires) merchants is called an acquiring bank,

merchant bank, or acquirer. Acquiring banks sign up merchants to accept payment cards for the

network and also arrange processing services for merchants. They can contract directly with the

merchant or indirectly through agent banks or other third parties.

A bank can be both an issuing bank and an acquiring bank, but banks most often specialize in

one function or the other. Merchant processing is a separate and distinct line of business from

credit card issuing. It is generally an off-balance sheet activity with the exception of merchant

reserves and settlement accounts, both of which are discussed later in this chapter. Merchant

processing involves the gathering of sales information from the merchant, obtaining authorization

for the transaction, collecting funds from the issuing bank, and reimbursing the merchant. It also

involves charge-back processing. The vast majority of merchant transactions are electronically

originated (as compared to paper-based) and come from credit card purchases at merchant

locations or the point-of-sale (POS). Merchant processing increasingly includes transactions

initiated via debit cards, smart cards, and electronic benefits transfer (EBT) products.

TRANSACTION PROCESS OVERVIEW

The payment networks are the center of the cardholder transaction process and maintain the flow

of information and funds between issuing banks and acquiring banks. In a typical cardholder

transaction, the transaction data first moves from the merchant to the acquiring bank (and

through its card processor

, if applicable), then to the Associations, and finally to the issuing

bank (and through its card processor, if applicable). The issuing bank ultimately bills the

cardholder for the amount of the sale. Clearing is the term used to refer to the successful

transmission of the sales transaction data. At this point, no money has changed hands; rather,

only financial liability has shifted. The merchant, however, needs to be paid for the sale.

Settlement is the term used to refer to the exchange of the actual funds for the transaction and its

associated fees. Funds to cover the transaction and pay the merchant flow in the opposite

direction: from the issuing bank to the Associations, to the acquiring bank, and finally to the

merchant. The merchant typically receives funds within a few days of the sales transaction.

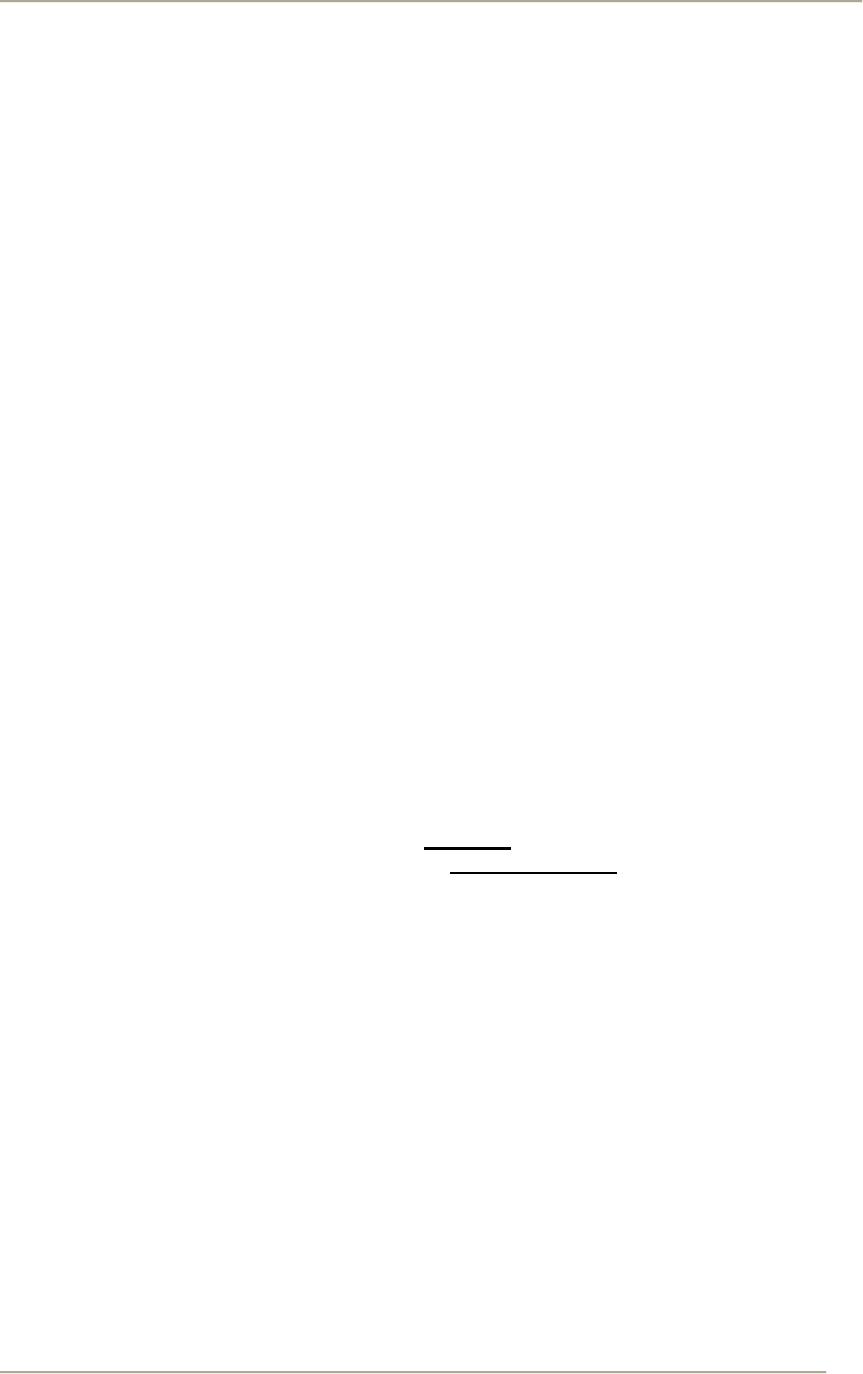

In a simple form, the clearing and settlement processes for payments can be illustrated with a

standard four-corners model (as discussed in the FFIEC IT Examination Handbook, Retail

Payment Systems Handbook (March 2004)). In this model, there is a common set of participants

for credit card payments: one in each corner (hence, the term four-corners model) and one in the

middle of the diagram. The initiator of the payment (the consumer) is located in the upper left-

hand corner, the recipient of the card payment (the merchant) is located in the upper right-hand

corner, and the relationships of the consumer and the merchant to their banks (the issuing bank

and the acquiring bank, respectively) reside in the bottom two corners. The payment networks

that route the transactions between the banks, such as Visa, are in the middle of the chart. The

information and funds flows for a typical credit card transaction are illustrated in a four-corners

model

13

labeled Exhibit D on the next page. Information flows are presented as solid lines while

funds flows are represented by dashed lines.

13

The model and discussion generally mirror the model and discussion that is presented in the FFIEC IT Examination

Handbook, Retail Payment Systems Handbook (March 2004).

March 2007 FDIC- Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

164

Merchant Processing

Step 1: The consumer pays a merchant with a credit card.

Steps 2 and 3: The merchant then electronically transmits the data through the

applicable Association’s electronic network to the issuing bank for

authorization.

Steps 4, 5, and 6: If approved, the merchant receives authorization to capture the

transaction, and the cardholder accepts liability, usually by signing the

sales slip.

Steps 7 and 8: The merchant receives payment, net of fees, by submitting the captured

credit card transactions to its bank (the acquiring bank) in batches or at

the end of the day

14

.

Steps 9 and 10: The acquiring bank forwards the sales draft data to the applicable

Association, which in turn forwards the data to the issuing bank.

The Association determines each bank’s net debit position. The Association’s settlement

financial institution coordinates issuing and acquiring settlement positions. Members with net

debit positions (normally the issuing banks) send funds to the Association’s settlement financial

institution, which transmits owed funds to the receiving bank (generally the acquiring banks).

Step 11: The settlement process takes place using a separate payment network

such as Fedwire

.

Step 12: The issuing bank presents the transaction on the cardholder’s next

billing statement

.

Step 13: The cardholder pays the bank, either in full or via monthly payments.

Exhibit D

Payment Network

(for instance, Visa

or MasterCard)

Consumer

Merchant

Issuing Bank

Acquiring Bank

1

6

2

5

8

9

11

7

11

3

4

10

12

13

14

Acquiring banks generally pay merchants by initiating Automated Clearing House (ACH) credits to deposit accounts at

the merchants’ local banks (possibly an agent bank). If an acquiring bank employs a third-party card processor, the card

processor usually prepares the ACH file.

March 2007 FDIC – Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection 165

Risk Management Examination Manual for Credit Card Activities Chapter XIX

Exhibit D is only a simplistic example of the variety of arrangements that can exist. The parties

for the transaction could be one of thousands of acquirers or issuers or one of millions of

merchants and consumers. Further, there are many other ways the arrangements can be

structured. For example, in on-us transactions, the acquiring bank and the issuing bank are the

same. Also, the timing of the payment to the merchant (step 8 of Exhibit D) varies. Some

acquiring banks pay select merchants prior to receiving funds from the issuing bank, thereby

increasing the acquiring bank’s credit and liquidity exposure. However, payment from the

acquiring bank to the merchant often occurs shortly after the acquiring bank receives credit from

the issuing bank.

The presence of third-party organizations coupled with the acquiring bank’s ability to sub-license

the entire merchant program, or part thereof, and the issuing bank’s ability to sub-license the

entire issuing program, or part thereof, to other entities also introduces complexities to the

transaction and fund flows. For example, because the cost of technology infrastructure and the

level of transaction volume are high for acquiring banks, most small acquiring banks rely on third-

party card processors to perform the functions. In addition, issuing banks often use card

processors to conduct several of

their services. In intra-processor transactions, the same third

party processes for both the acquiring bank and the issuing bank. Under the by-laws and

operating rules/regulations of the Associations, the issuing banks and acquiring banks are

responsible for the actions of their contracted third-parties, respectively.

A merchant submits sales transactions to its acquiring bank by one of two methods. Large

merchants often have computer equipment that transmits transactions directly to the acquiring

bank or its card processor. Smaller merchants usually submit transactions to a vendor that

collects data from several merchants and then transmits transactions to the acquiring banks.

RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH MERCHANT PROCESSING

Some bankers do not understand merchant processing and its risks. Attracted to the business by

the potential for increased fee income, they might underestimate the risk and not employ

personnel with sufficient knowledge and expertise. They also might not devote sufficient

resources to oversight or perform proper due diligence reviews of prospective third-parties. Many

banks simply do not have the managerial expertise, resources, or infrastructure to safely engage

in merchant processing outside their local market or to manage high sales volumes, high-risk

merchants, or high charge-back levels. Many of a bank’s risks may be interdependent with

payment system operators and third parties. For example, the failure of any payment system

participant to provide funding for settlement may precipitate liquidity or credit problems for other

participants, regardless of whether they are party to payments to or from the failing participant.

For banks that engage in merchant programs or that are contemplating engaging in such

programs, examiners should look for evidence that management understands the activity’s risks

which include credit, transaction, liquidity, compliance, strategic, and reputation risk. A failure by

management to understand the risks and provide proper controls over such risks can be very

problematic, and even lethal, to the bank. Take, for example, the case of National State Bank,

Metropolis, Illinois. Inadequate control of the credit and transaction risks associated with its

merchant processing activities contributed to a high volume of losses that ultimately depleted

capital, threatened the bank’s liquidity, and led to its closing by the Office of the Comptroller of

the Currency (OCC) in December 2000.

15

15

As per press release PR-90-2000.

March 2007 FDIC- Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

166

Merchant Processing

Credit Risk

A primary risk associated with merchant processing is credit risk. Even though the acquiring

bank typically does not advance its own funds, processing credit card transactions is similar to

extending credit because the acquiring bank is relying on the creditworthiness of the merchant to

pay charge-backs. Charge-backs are a common element in the merchant processing business

and are discussed in more detail later in this chapter. They can result from legitimate cardholder

challenges, fraud, or the merchant’s failure to follow established guidelines. Charge-backs

become a credit exposure to the acquiring bank if the merchant is unable or unwilling to pay

legitimate charge-backs. In that case the acquiring bank is obligated to honor the charge-back

and pay the issuing bank which could result in significant loss to the acquiring bank. In a sense,

the acquiring bank indemnifies a third party (in this case, the issuing bank that in turn indemnifies

the cardholder) in the event that the merchant cannot or does not cover charge-back. Banks

have been forced to cover large charge-backs when merchants have gone bankrupt or

committed fraud. Acquiring banks control credit risk by using sound merchant approval

processes and closely monitoring merchant activities.

Transaction Risk

Acquiring banks are faced with the transaction risk associated with service or product delivery

because they process credit card transactions for their merchants daily. The risk can stem from a

failure by the bank or any party participating in the transaction to process a transaction properly

or to provide adequate controls. It can also stem from employee error or misconduct, a

breakdown in the computer system, or a natural catastrophe. The acquiring bank needs an

adequate number of knowledgeable staff, appropriate technology, comprehensive operating

procedures, and effective contingency plans to carry out merchant processing efficiently and

reliably. A sound internal control environment is also necessary to ensure compliance with the

payment networks’ rules. Formal reconciliation processes are also essential to limiting risk.

The high transaction and sales volume normally encountered with merchant processing

programs creates significant transaction and liquidity risks. A failure anywhere in the process can

have implications on the bank. Examples include an issuing bank's inability to fund settlement to

the acquiring bank or a processing center’s failure to transmit sales information to the issuing

bank, thus resulting in a delay of or failure of funding to the merchant bank.

Liquidity Risk

Liquidity risk can be measured by the ability of the acquiring bank to timely transmit funds to the

merchants. Acquiring banks often limit this risk by paying merchants after receiving credit from

the issuing bank. If the acquiring bank pays the merchant prior to receiving credit from the

issuing bank, the acquiring bank could sustain a loss if the issuing bank is unable or unwilling to

pay. Some acquiring banks delay settlement and pay merchants one day after receiving the

funds from the issuing bank. The delay allows the acquiring bank time to perform fraud reviews.

For delayed settlement, which most commonly occurs when transactions are identified as

suspicious or unusual, management is expected to have established formal procedures.

Because merchant deposits can be volatile, risk may also arise if the acquiring bank becomes

reliant on the merchant’s deposits as a funding source for other bank activities. Furthermore,

substantial charge-backs could potentially strain the bank’s financial condition and/or reputation

to such a degree that its creditors may withdraw availability of borrowing lines.

Associations guarantee settlement for transactions that pass through interchange. As a result,

they may require collateral pledges/security if a bank's ability to fund settlement becomes

questionable. This can create significant liquidity strains and potentially capital difficulties,

depending on the size of the collateral requirement and/or the financial condition of the bank.

March 2007 FDIC – Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection 167

Risk Management Examination Manual for Credit Card Activities Chapter XIX

The Associations' rules allow them to assess the banks directly through the settlement accounts

if the bank is not forthcoming with the collateral.

Compliance Risk

Compliance risk arises from failure to follow payment networks’ rules and regulations, clearing

and settlement rules, suspicious activity reporting requirements, and a myriad of other laws,

regulations, and guidance. It can lead to fines, payment of damages, diminished reputation,

reduced franchise value, limited business opportunities, reduced expansion potential, and lack of

contract enforceability. Acquiring banks can limit compliance risk by ensuring a structured

compliance management program is in place, the internal control environment is sound, and staff

is knowledgeable. They can also limit risk by providing staff with access to legal representation

to ensure accurate evaluation of items such as new product offerings, legal forms, laws and

regulations, and contracts.

Strategic Risk

Strategic risk arises from adverse business decisions or improper implementation of those

decisions. A failure by management to consider the bank’s merchant processing activities in the

context of its overall strategic planning is normally cause for concern. A decision to enter,

maintain, or expand the merchant processing business without considering management’s

expertise and the bank’s financial capacity is also normally cause for concern. Examiners should

also pay close attention to how the acquiring bank plans to keep pace with technology changes

and competitive forces. Examiners should look for evidence that the strategic planning process

identifies the opportunities and risks of the merchant processing business; sets forth a plan for

managing the line of business and controlling its risks; and considers the need for a

comprehensive vendor management program. An evaluation of management's merchant

processing expertise is critical to judging strategic risk. The bank's overall programs for audit and

internal controls, risk management systems, outsourcing of services, and merchant program

oversight are key to controlling the strategic risk.

Reputation Risk

Reputation risk arising from negative public opinion can affect a bank’s ability to establish new

relationships or services or to continue servicing existing relationships. This risk can expose the

bank to litigation, financial loss, or damage to its public image. The bank’s business decisions for

marketing and pricing its merchant processing services can affect its reputation in the

marketplace. Reputation risk is also associated with the bank’s ability to fulfill contractual

obligations to merchants and third parties. Most notably, the outsourcing of any part of the

merchant processing business easily increases reputation risk. Decisions made by the acquiring

bank or its third-parties can directly cause loss of merchant relationships, litigation, fines and

penalties as well as charge-back losses. Concerns normally arise when the acquiring bank does

not maintain strong processes for performing due diligence on prospective merchants and third-

parties or perform ongoing evaluations of existing merchant and third-party relationships.

MANAGEMENT

Examiners should expect that management fully understand, prior to becoming involved in

merchant processing and continuing thereafter, the risks involved and its own ability to effectively

control those risks. Merchant programs are specialized programs that require management

expertise, significant operational support, and rigorous risk-management systems. It can be a

profitable line of business but, if not properly controlled, can result in significant risk to the bank.

March 2007 FDIC- Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

168

Merchant Processing

Examiners should determine whether qualified management has been appointed to supervise

merchant activities and to implement a risk management function that includes a merchant

approval system and an ongoing merchant review program for monitoring credit quality and

guarding against fraud. Bank staff’s knowledge and skill-sets are expected to be commensurate

with the risks being taken. For example, personnel responsible for processing charge-backs

should have the technical knowledge and understanding of charge-back rules, and personnel

responsible for approving merchant applications should have the ability to properly evaluate

creditworthiness and identify high-risk merchants.

Examiners assessing risks of merchant programs should direct their attention to situations in

which management has not put proper risk measurement systems in place to operate, monitor,

and control the activity effectively. This includes situations that evidence the absence of regular

management reports detailing pertinent information. Key reports generally include new merchant

acquisitions, merchant account attrition, merchant portfolio composition, sales volumes, charge-

back volumes and aging, fraud, and profitability analyses.

Examiner attention should be given to instances in which comprehensive, written merchant

processing policies and procedures are absent or are not adequate for the size and complexity of

operations. Necessary components of policies and procedures generally include:

• Clear lines of authority and responsibility (for example, the level of approval required

to contract with certain types of merchants).

• Adequate and knowledgeable staff.

• Markets, merchant types, and risk levels the bank is and is not willing to accept.

• Limits on the individual and aggregate volume of merchant activity that correlates

with the bank’s capital structure, management expertise, and ability of operations to

accommodate the volume (e.g., human and systems resources) as well as with

merchants’ risk profiles.

• Goals for portfolio mix and risk diversification, including limits on the volume of sales

processed for higher-risk merchants and that take into account the level of

management expertise.

• Merchant underwriting and approval criteria.

• Procedures for monitoring merchants, including financial capacity, charge-backs and

fraud (regardless of who originates the merchants for the bank).

• Criteria for determining appropriate holdback

or merchant reserve accounts.

• Procedures for settlement, processing retrieval requests

and charge-backs,

handling complaints, monitoring and reporting of fraud, and training personnel.

• Third-party risk management controls.

• Guidelines for accepting and monitoring agent banks.

• Guidelines for handling policy exceptions.

• MIS to keep management sufficiently informed of the condition of, and trends in, the

merchant program.

• Audit coverage.

CAPITAL

Examiners should insist that the bank hold capital sufficient to protect against risks from its

merchant business. In addition, they should determine whether management has established

sound risk limits on the merchant processing volume based on the bank's capital structure, the

risk profile of the merchant portfolio, and the ability of management to monitor and control the

risks of merchant processing.

Associations limit the processing volume a bank can generate based upon the bank's capital

structure, high-risk merchant concentrations, and charge-back rates. Banks operating outside

the established thresholds (which may vary and are subject to change) are generally considered

March 2007 FDIC – Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection 169

Risk Management Examination Manual for Credit Card Activities Chapter XIX

to be high-risk acquiring banks by the applicable Association and may be subject to additional

activity limits or collateral requirements.

No specific regulatory risk-based capital allocation(s) for merchant processing activities, which,

as mentioned, are typically off-balance sheet, exist. Nevertheless, capital regulations permit

examiners to require additional capital if needed to support the level of risk. Examiners

frequently consider these measurements that take into account the volume of merchant activity:

• Risk Weighted Off-Balance Sheet Items for Merchant Processing = Average monthly

merchant sales (Annual Merchant Sales/12) X 2.5 X 20 percent (conversion factor for

off-balance sheet items) X 100 percent (risk weight category)

16

.

• Tier 1 capital / (Average Total Assets + Risk Weighted Off-Balance Sheet Items for

Merchant Activity).

MERCHANT UNDERWRITING

Evidence should corroborate that the bank scrutinizes prospective merchants with the same level

of diligence used to properly evaluate prospective borrowers. Concerns may arise when the

bank’s underwriting does not consider the merchant's ability to cover projected charge-backs as

well as its potential risk for fraud, high charge-back rates, and business failure. Merchant

underwriting and approval policies generally:

• Define criteria for accepting merchants (for example, acceptable business types, time

in business, location, sales and charge-back volumes, and financial capacity).

• Establish underwriting standards for the review of merchants.

• Define what information is required on the merchant application.

• Stipulate what information is required in the merchant agreement.

• Outline procedures and time frames for periodic review of existing relationships.

Merchant Review and Approval

Merchant underwriting provides an opportunity to reject a merchant that the acquiring bank

determines has an unacceptable history of charge-back volumes, has a weak financial condition,

is not operating a valid business, or is otherwise not acceptable for the bank’s program. Limits

for personnel approving new merchant accounts are usually based on the merchant's sales

volume, and situations in which the designated bank personnel do not have appropriate levels of

credit expertise in relation to that volume are cause for concern. Further, if the acquiring bank

uses information collected by Independent Sales Organizations (ISOs) / Merchant Service

Providers (MSPs), examiners should look for policies and controls to be in place for

substantiating the quality of the information provided. In addition to exception guidelines and

documentation requirements, underwriting standards generally include:

• A signed merchant application.

• A signed merchant processing agreement.

• A signed corporate resolution, if applicable.

• An on-site inspection report.

• Analysis of credit bureau reports on the principal(s) of the business.

• Evaluation of financial statements, tax returns and/or credit reports on the business.

16

This calculation converts the off-balance sheet activity (merchant sales settled) to an on-balance sheet risk-weighted

item. The 2.5 figure represents a 2.5 month average liability for charge-backs that is based on the premise that most

charge-backs run off within 2.5 months. Technically, there is a potential 6 month window of charge-back liability. The 20

percent figure is the factor to convert the off balance sheet transactions subject to recourse to an on-balance sheet item.

The 100 percent figure represents the risk weight applied based on capital regulations. The resulting risk weighted off-

balance sheet items for merchant processing would be included in the denominator of the risk based capital ratios.

March 2007 FDIC- Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

170

Merchant Processing

• Analysis of prior merchant activity, such as the latest monthly statements from the

most recent processor.

• Analysis of projected sales activity (for instance, average ticket amount,

daily/monthly sales volume).

• Assessment of any existing relationship (for example, a loan) with the bank.

• Consideration of the line of business and/or the product(s) offered by the merchant.

• Verification of trade and bank references.

• Evidence as to whether the merchant is on the Member Alert To Control High Risk

Merchants (MATCH

) system.

Principals:

Proper review by management normally includes conducting a background check on the

business’s principal(s), scrutinizing personal credit reports for derogatory information, and

verifying addresses. Where appropriate and allowed by law, management may also perform a

criminal background check.

MATCH:

Association regulations state that acquiring banks must check MATCH before approving a

prospective merchant. The database contains a list of merchants that have been terminated for

cause or that have made multiple applications for merchant accounts (because submitting

applications to more than one acquiring bank simultaneously might indicate fraud). If an

acquiring bank denies permission to accept cards to a merchant because of adverse processing

behavior and fails to add it to the MATCH list, the acquiring bank can be liable for losses another

provider might suffer from that merchant.

17

If a merchant is listed on MATCH, management is expected to contact the listing bank regarding

the termination reasons. MATCH status can help a bank determine whether to implement

specific actions or conditions if a merchant is accepted. Examiners should pay attention to

instances in which management has not carefully investigated a merchant listed on MATCH or in

which their decision to accept or refuse a merchant has been solely based on the merchant being

listed or not being listed on MATCH.

On-Site Inspection:

The goal of on-site inspections is to verify a merchant’s legitimacy. The absence of

documentation of the inspections, including photographs and a written inspection report normally

is cause for concern as are situations in which the inspection was conducted by an individual who

has a financial interest in its outcome. Acquiring banks signing merchants remotely sometimes

find performing inspections themselves difficult or expensive. Often other acquiring banks or

third parties will perform site inspections on an exchange or fee basis. In these cases, examiners

need to assess whether management is well-informed of the other parties’ inspection procedures

and ensures that the procedures are, at a minimum, consistent with procedures management

would use if conducting a proper inspection itself.

Products and Marketing:

The merchant’s line of business and/or the products offered as well as its marketing practices are

key factors for management to consider when it evaluates the credit quality of a merchant. The

Associations segment merchants according to activity because the type of activity often is a good

indicator of risk. Thus, it stands to reason that examiners may expect acquiring banks to

17

According to the article entitled ”Merchant Acquirers and Payment Card Processors: A Look Inside the Black Box,”

authored by Ramon P. DeGennaro, and housed in the First Quarter 2006 edition of the Economic Review (Federal

Reserve Bank of Atlanta).

March 2007 FDIC – Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection 171

Risk Management Examination Manual for Credit Card Activities Chapter XIX

continually analyze their merchant portfolios along similar guidelines. Acquiring banks typically

compile a prohibited or restricted merchant list which includes the types of merchants they are

unwilling to sign or are willing to sign only under certain circumstances.

While the extent of product and marketing evaluations varies, considerations normally include

review of the merchant’s business plans, merchandise, and marketing practices and materials

(for example, catalogs, brochures, telemarketing scripts, and advertisements). In addition,

shipping, billing, and return policies can be reviewed for unusual or inappropriate practices (for

instance, customers being billed long before merchandise is shipped). These considerations can

help determine, among other things, if: the business is of a type that typically has high charge-

back rates; the merchant is selling a legitimate product; sales methods are legitimate and not

deceptive; product quality and price are consistent with projected sales and charge-back rates;

and customers will be satisfied with products ordered. Merchants offering low-quality products or

services tend to incur more charge-backs, thus dissuading many banks from signing them.

The merchant's sales volume and time frame within which product delivery is completed are other

considerations to evaluate risk. Generally, the greater the sales volume and the longer the time

between transactions and product delivery, the greater the risk. For example, when a restaurant

closes, an acquiring bank typically has less exposure to charge-backs for undelivered goods and

services. In contrast, the failure of a travel agency could expose an acquiring bank to substantial

charge-backs due to the high volume of reservations common in the travel agency business.

Certain types of merchant businesses can present increased risk. Although there are many

reputable merchants whose sales transactions occur without a credit card being present (card-

not-present merchants), these merchants generally present higher charge-back risks for

acquiring banks. In particular, mail order and telemarketing (MO/TO) merchants and adult

entertainment services merchants, in aggregate, tend to display elevated incidents of charge-

backs. Merchants without an established storefront (for example, door-to-door salesman and flea

market vendors) also typically pose greater risk for charge-backs. The risk of charge-back is also

higher if the merchant sells products for future/delayed delivery

, such as airline tickets, health

club memberships, travel clubs, or internet purchases. The increased risk associated with future

delivery of products results, in part, because customer disputes are normally not triggered until

the date of delivery. High charge-back rates are also generally associated with certain selling

methods, such as sales pitches involving gifts, cash prizes, sweepstakes, installment payments,

multi-level marketing, and automatic renewals unless the consumer opts out. Association

regulations define certain broad business categories as high-risk merchants. These categories in

general present higher risk, but each individual merchant in the category may not necessarily be

high risk. Appropriate procedures and risk controls for high-risk merchants generally include:

• Criteria for determining the types of merchants the bank is or is not willing to sign and

under what circumstances.

• Increased emphasis on underwriting considerations regarding products and

marketing in evaluating the merchants.

• Limitations on the volume of high-risk merchant transactions processed relative to

the bank’s total merchant portfolio.

• Criteria for determining the appropriate level of holdback or reserve accounts to

sufficiently cover the level of credit risk.

• Appropriate pricing of these merchants in relation to the charge-back risk and any

costs associated with increased monitoring.

• Heightened monitoring and problem resolution. For example, for charge-back

monitoring, banks may set lower charge-back thresholds for required remedial action

and/or a shorter timeline for problem resolution for those merchants exceeding

acceptable charge-back thresholds.

• Compliance with bankcard regulations regarding registration of certain high-risk

merchants and assigning proper Merchant Category Codes (MCC)

to merchants.

March 2007 FDIC- Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

172

Merchant Processing

Merchant Agreements

If management has not sought legal advice when developing merchant agreements and/or

referred to network guidelines for contracting, closer scrutiny of such agreements may be

warranted. Typical contents of a merchant agreement include but are not limited to:

• Fees and pricing.

• Merchant requirements at POS.

• Requirements for cardholder information security.

• Prohibition of split sales drafts

and laundering of sales drafts.

• Merchant liability (for example, charge-backs and reserves).

• Notification of ownership changes or substantive marketing and product changes.

• Right to hold funds (for example, bank's right to freeze deposits when fraudulent

activity suspected).

• Termination provisions.

• Internet provisions (for example, encryption and web-site displays).

Periodic Review

Concerns normally become elevated when management is not monitoring the financial condition

of high-volume and high-risk merchants on an ongoing basis and/or when the bank’s policy has

not addressed the frequency of reviews and the size of merchants requiring reviews. Examiners

should assess management’s practices for considering volume, concentrations, high-risk

industries, and charge-back history in establishing the thresholds for periodic reviews.

Depending on the composition of the bank’s merchant portfolio, examiners may not necessarily

expect the bank to conduct credit reviews of smaller merchants on an ongoing basis if the bank

used sound underwriting guidelines at acquisition and if the bank is using strong controls to

monitor all merchant transactions, including fraud and charge-back monitoring. Examiners might

observe cases in which databases (for items such as risk scores and bankruptcy filings) are used

to periodically screen the merchant portfolio.

Communication between merchant program and loan personnel regarding changes in the

merchant’s credit quality is key part of assessing any shared banking relationships. For example,

an unacceptable charge-back rate for a merchant might indicate emerging credit quality problems

that could trigger the need to review any lending relationships with the merchant. Likewise,

concerns that identify merchants as problem borrowers could trigger the need to review merchant

arrangements. If credit information shows deterioration in the merchant’s financial condition, the

bank may want to reduce its risk exposure from merchant processing. For instance, when

dealing with a financially-unstable merchant, the bank might require a holdback or security

deposit, as discussed later in this chapter.

Internet Merchants

The lower level of barriers encountered when setting up an Internet merchant increases the risk

of fraudulent businesses or businesses with minimal financial resources being established

compared to the risks associated with traditional merchants. This risk elevates the need for

acquiring banks to conduct thorough underwriting reviews of internet merchants. Whether fraud

and charge-back risks warrant additional risk-mitigation techniques, such as delaying settlement

or setting up reserves, is a critical decision that normally occurs during the underwriting process.

Electronic commerce via the Internet poses additional privacy and security concerns. The

absence of or weak transaction and data security controls for customer transactions and storage

of customer information are cause for concern. Secured servers and data encryption

technologies help to protect data and transaction integrity. Other items considered normally

include whether the merchant meets the following general web site display guidelines:

March 2007 FDIC – Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection 173

Risk Management Examination Manual for Credit Card Activities Chapter XIX

• Description of goods and services offered.

• Customer service number.

• Company’s e-mail address.

• Statement regarding security controls.

• Delivery methods and timing.

• Refund and return policies.

• Privacy statements (permissible uses of customer information).

PRICING

One of the key aspects of a successful merchant program is appropriately setting the fees that

the merchant will be charged for sales transactions and acquiring bank services. Merchant

pricing is extremely competitive, especially for large- and national-scale merchants who generate

high transaction volumes. High transaction volumes can lead to economies of scale and possibly

increased income. Examiner should look for evidence that banks have adopted a pricing policy

that outlines the methods used for pricing, authority levels, and repricing procedures. A pricing

policy can facilitate consistency in pricing practices and help optimize profit margins.

Acquiring banks use various methods to price merchants. Smaller merchants are frequently

priced with a single discount rate based on merchant volume and average ticket size. Acquiring

banks frequently use unbundled pricing for medium to large merchants. Unbundled pricing is the

method of assigning fees for the cost of each service used. Examples of unbundled services

include interchange, authorizations, and charge-backs. Other fees may include, but are not

limited to: statement preparation, application, customer service, membership, maintenance, and

penalty fees (for example, for violating payment network rules).

Examiners should evaluate the bank’s practices for ensuring that pricing is consistent with the

risk posed by the merchant. Acquiring banks sometimes use a pricing model to determine the

target discount rate. They might maintain one or more pricing models, with model usage driven

by the merchant's sales volume and/or industry classification. Pricing models allow the acquiring

bank to quickly substitute variables regarding sales volumes, average ticket size, revenues and

expenses to produce a projected profit margin. A failure of the pricing model to include all direct

and indirect expenses may render the model’s results meaningless. A model’s accuracy

depends upon the reasonableness of the assumptions used.

Pricing Components

Discount Rate:

Acquiring banks assign a discount rate for each merchant when the merchant agreement is

signed. The discount rate is the percentage that gets “discounted” off the transaction amount

that is paid to the merchant, hence the term discount rate. In a simple case, the discount

represents a single rate charged to a merchant based on the merchant’s sales volume. For

example, a merchant with a 2 percent discount rate receives $98 for a $100 credit card sale.

Most merchant agreements allow the acquiring bank to change the discount rate for various cost

increases. Numerous factors influence the discount rate charged, including, but not limited to,

the transaction method, processing volume, and type of merchant business. For example,

merchants who use electronic data capture (EDC)

are typically charged lower discount rates

than paper-based merchants. Discount rates generally range from 1 to 4 percent for small to

medium-size merchants and sometimes well below that range for large-volume merchants.

When considering the range of discount rates used by the bank, examiners should call on

management to readily explain outliers, including those that are well below the normal range.

Banks sometimes give merchants a favorable discount rate because of existing commercial loan

March 2007 FDIC- Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

174

Merchant Processing

or deposit relationships. In other cases, the discount rate is favorable due to a credit card

equipment lease arrangement. Packaging may be an acceptable practice, but does not eliminate

the need to measure the overall profitability of a merchant relationship. Further, examiner

attention should be drawn to situations in which management has offered favorable discount

rates to insiders or their related interests.

Interchange Fees:

Interchange fees represent compensation paid by the acquiring bank to the issuing bank. Thus,

they are recorded as an expense on the acquiring bank’s income statement and as a revenue

source on the issuing bank’s income statement. Interchange fees are based on several factors

such as volume, size, and type of transaction and are usually set by the Associations. They

average less than two percent of the purchase price and are typically one of many considerations

in determining the size of the discount rate that the acquiring bank charges the merchants. (For

on-us transactions, interchange may be reduced, if not entirely eliminated.) A number of

merchants and merchant groups have filed lawsuits alleging that the interchange fees set by the

Associations for credit card transactions violate anti-trust laws and that the fees paid to accept

payment cards are too high. In last quarter of 2006 the Associations began offering pubic access

to interchange rate information.

Processing Fees:

Processing fees cover the costs associated with data processing services and vary depending on

the size and number of transactions the merchant submits per batch. The processing fee may

include data capture and authorization costs. It might go directly to the bank if it handles the

processing or to the bank’s third-party processor.

ISO/MSP Fees:

The ISO/MSP fee is the amount the acquiring bank pays the ISO/MSP for services provided. It is

negotiated and often represents a percentage of the volume that the ISO/MSP-sponsored

merchants bring to the bank. The fee agreement between the bank and the ISO/MSP is normally

considered when pricing merchants obtained through an ISO/MSP.

Agent Bank Commission:

The agent commission is a fee passed to the agent bank for signing a merchant. This fee could

be built into the discount rate or be assessed separately.

Other Income:

Acquiring banks sometimes offer other programs to generate fee income (for instance, equipment

leasing). Instances in which management has not researched the legal and compliance aspects

of products or services offered or has not priced the programs adequately warrant scrutiny.

Monitoring Pricing

Examiners should evaluate management’s practices for ensuring that merchants are priced

appropriately throughout the life of the contract. Best practices by management may include

verifying actual volumes and ticket sizes after signing a new merchant (for example, at six

months into the relationship) to ensure consistency with volumes and ticket sizes anticipated.

Examiners should assess management’s practices for ensuring the discount rate is in line with

the application estimate and original pricing model assumptions. In general, a failure by

management to review all significant merchants for repricing at least annually elevates concern.

Further, if any merchants are or have been unprofitable, examiners should accordingly inspect

management’s repricing practices for those merchants. Merchant agreements typically allow

March 2007 FDIC – Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection 175

Risk Management Examination Manual for Credit Card Activities Chapter XIX

acquiring banks to increase pricing at any time during the contract’s life.

Profitability Analysis

Merchant programs can be profitable. Although competition with third-party processors has

lowered margins, banks have been able to compete due to their strong marketplace presence.

Banks are able to generate new merchant accounts through their branch networks and existing

customer relationships.

Merchant processing is characterized as a high transaction volume, low profit margin business.

Only efficiently run departments with strong cost controls can operate profitably. Examiners

should analyze profitability reports used by the bank to measure the profitability of the merchant

processing operations to determine if it is consistent with the size and complexity of the

operations. Reports should detail key performance measures such as net income to sales and

net income per item. Ideally, it should be able to segment profitability by merchant, acquisition

channel, and industry.

Examiners should normally expect profitability analyses for merchant operations to be distinctly

separate from the analyses of other banking activities and to include all direct and indirect costs.

Direct costs include costs such as those for internal data processing, merchant accounting, fraud

and charge-back losses, personnel, and occupancy. Indirect costs may include corporate

overhead expenses such as those for human resources, legal, and audit services. The level of

detail and frequency of board reporting is contingent on the size of the operation in relation to the

overall operations of the bank and its capital base.

FRAUD MONITORING

Management’s ability to quickly detect fraudulent activity is important in controlling losses. The

merchant, then its acquiring bank, are the parties liable for certain types of losses. Persons

possessing stolen credit cards sometimes take advantage of unsuspecting store clerks, or

merchants sometimes perpetrate fraud. Merchant fraud can be extremely costly if not discovered

quickly. Examples of merchant fraud include factoring

and draft laundering. New merchant

accounts are particularly susceptible to fraud such as bust-out scams

. Examiners should insist

that banks have a fraud detection system to identify and monitor potentially fraudulent activity.

Fraud Detection Methods

Fraud identification that relies exclusively on excess charge-back activity analysis is normally

cause for concern because there are a number of other indicators that can point to fraud. A

primary tool used by management for fraud detection is an exception report that details variances

from a multitude of parameters established at account set-up. Along with charge-backs, basic

parameters usually include daily sales volume, average ticket size, multiple purchases of the

same dollar amount, multiple use of the same cardholder number, percentage of keyed versus

swiped transactions (because keyed transactions frequently are associated with card-not-present

transactions which are normally higher-risk), number of authorizations declined, authorizations

during non-business hours, and high volume of authorizations in relation to transactions. A daily

exception report lists merchants that are outside of any of the parameters.

Most large-volume processors have established exception parameters based on industry or

merchant type. Examiners should review management’s practices for periodically updating

parameters. For example, management might set the daily sales threshold at a percent of a prior

timeframe’s activity (for instance, 110 percent of the three months’ average). The margin allows

for normal growth of the merchant and compensates for seasonal sales patterns.

March 2007 FDIC- Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

176

Merchant Processing

Some banks use neural network technologies for fraud detection. These complex computer

programs can compare each transaction against the merchant’s prior sales patterns. Though

more sophisticated than a traditional exception report, smaller merchant processors may be

unwilling or unable to purchase these technologies on an ongoing basis. Instead, some acquiring

banks selectively route higher-risk transactions through a neural network while confining the

remainder of transactions to exception reporting.

Some banks also use Informational databases (such as those for scoring, bankruptcy, trade, and

fraud) to identify at-risk merchants. Merchants that have financial or legal difficulties often have a

higher propensity to falsify transactions.

Associations provide educational materials to acquiring banks and merchants about the

industry’s latest fraud detection techniques. They also prepare fraudulent activity reports for

each acquiring bank. The reports are not intended to replace the bank's own fraud system.

Rather, examiners should expect to see that such reports supplement the internal system.

Certain circumstances require management to document its plan to correct a merchant’s

unacceptable sales practices.

Inactive merchant accounts can signal potential fraud. For example, inactivity could signal a

bust-out scam wherein a fraudulent merchant signs with several acquiring banks simultaneously,

moving from one to the next as the scam is perpetrated or detected. When exception reports flag

an inactive account, management normally follows up with the business owner.

Other potential warning signs of fraud generally include:

• Evidence that credit card purchases have been intentionally structured by a

merchant to keep individual amounts below the "floor limit" to avoid approval

requirements.

• Merchant account activity that reflects a substantial increase in the number and/or

size of charge-backs.

• Merchant’s deposit of sales drafts made payable to a business or businesses other

than the business named on the account.

• Merchant’s frequent request that funds be wire transferred from the merchant

account to other institutions in other parts of the country or to offshore institutions

almost immediately after deposits are made.

• Merchant that is engaged in telemarketing activities and is the subject of frequent

customer complaints.

• Merchant account deposits that appear to exceed the level of customer activity

observed at the merchant’s place of business.

• Merchant that has access to electronic data capture equipment but frequently inputs

credit card account numbers manually (for example, if manually keyed transactions

exceed 10 percent of total transactions).

• Merchant that has a sudden or unexplained increase in the level of authorization

requests from a particular merchant location.

Fraud Investigations

Examiners must expect management to take swift action when it encounters suspicious

transactions or other suspicious activity. Management’s investigation may include verifying

purchases with the issuing bank and/or obtaining copies of paper-based transaction tickets from

the merchant. An acquiring bank’s quick response will help minimize losses to it and the issuer

as well as provide timely information to law enforcement agencies. Changes in a merchant's

business operations such as changes in ownership, business principals, bank accounts,

merchandise, sales methods, or target market normally also warrant an investigation.

March 2007 FDIC – Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection 177

Risk Management Examination Manual for Credit Card Activities Chapter XIX

Merchant agreements normally allow the acquiring bank to delay settlement until questionable

transactions are resolved. Once fraud is suspected, management must follow Suspicious Activity

Report (SAR) guidelines. Examiners should evaluate the bank’s processes for terminating

fraudulent merchant accounts and placing such merchants on MATCH. They should also

consider the acquiring bank’s and its processor’s practices for suspending or blocking settlement

and authorization processing to a terminated merchant's account. Such procedures are intended

to prevent further deposits and account testing

.

CHARGE-BACK PROCESSING

Credit risk arising from charge-backs is an acquiring bank’s primary risk and can result in

significant financial loss. If a merchant is unable to pay its charge-backs, the acquiring bank

must pay the issuing bank. Large charge-back losses can also result from deliberate fraud

undertaken by the merchant. For example, a merchant might sell deceptive or misleading

merchandise or never deliver the product. Authorization issues, inaccurate or incomplete

transaction information, and processing errors can also result in charge-backs. Charge-backs

are governed by a complex set of rules and time limits that can be costly to merchants and

acquiring banks if disregarded. Charge-back losses realized by the bank are listed as other non-

interest expense on the Call Report.

The most effective preventive measure against charge-back losses is thorough underwriting prior

to merchant acceptance. Nonetheless, examiners should expect that an acquiring bank have

strong controls in place to accurately and timely process charge-backs and retrieval requests.

The bank may lose a charge-back dispute (thus resulting in a loss) if it does not adhere to

charge-back rules. The absence of effective charge-back monitoring to identify problem

merchants for remedial action normally draws examiner attention. Quickly considering problem

merchants for termination may help avoid or limit loss.

Charge-Back Transaction Flow

Cardholders initiate charge-backs, for instance when they are dissatisfied with the product, did

not receive the merchandise or service, or did not authorize the charge. A consumer first tries to

resolve the dispute with the merchant. If unsuccessful, the consumer informs the issuing bank

about the dispute, and the issuing bank posts a temporary credit to the cardholder’s account.

The issuing bank then requests documentation from the merchant to authenticate the transaction

and possibly resolve the dispute. If the dispute is upheld, the amount is charged back to the

merchant's account and the consumer does not pay for the disputed charge. The consumer has

60 days from the day he or she receives the statement to report a dispute to the issuing bank.

Issuing banks can also initiate charge-backs when the merchant does not follow proper card

acceptance and authorization procedures or when there is a problem with the credit card account

(for example, it is not valid or has been terminated). The acquiring bank's contingent charge-

back liability generally spans 90 to 120 days (but up to 180 days for certain transactions).

Associations have strict charge-back processing regulations. For example, charge-backs occur

when a merchant fails to provide copies of requested sales tickets. If the merchant does not fulfill

retrieval requests within prescribed time frames, it loses the charge-back dispute. Merchants

must also follow other card acceptance procedures, including obtaining authorizations, as

depicted in the governing documents.

Charge-Back Monitoring

The Associations notify acquiring banks about high charge-back merchants. Once management

has received notification of excessive charge-back activity, examiners should expect

management to promptly take appropriate steps to bring charge-back rates down to acceptable

March 2007 FDIC- Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

178

Merchant Processing

levels. The steps may include, but are not limited to, reviewing procedures with merchants or

developing a detailed and comprehensive charge-back reduction plan. If the charge-back

volume is not sufficiently reduced within established timeframes, the Associations may impose

substantial fines against the acquiring bank.

Although the Associations notify acquiring banks about merchants with excessive levels of

charge-backs, examiners normally have concern when an acquiring bank’s own risk

management practices do not detect such merchants or when charge-back processing staff is not

alert for merchants with excessive retrieval requests or charge-backs. Numerous charge-backs

could indicate an unscrupulous merchant or a need for additional training.

Risk Mitigation for Charge-Backs

Acquiring banks often establish specific merchant reserve accounts, or holdback reserves, for

higher-risk or high-charge-back merchants. Holdback reserves are also used to limit a bank’s

credit risk when the merchant’s product or service involves future/delayed delivery. They are

funded by a lump sum payment or by withholding part of each day’s proceeds. Examiner should

expect these types of specific reserve accounts to be adequately funded.

The acquiring bank might also fund a general allowance account, similar to the ALLL (although

not commingled therewith), for a portfolio of merchant accounts. The method used to determine

the allowance allocation varies but is typically based on contingent charge-back exposure for the

entire portfolio. Such an allowance is reported as an “other liability.” Examiners should analyze

management’s merchant reserving methods to determine whether these types of allowances are

sufficiently funded.

An acquiring bank might also obtain merchant charge-back insurance which is intended to

provide protection against uncollectible charge-backs. While insurance products potentially

provide some level of protection, they are not a substitute for strong risk management practices.

Insurance contracts frequently include significant limitations or restricting clauses that constrain

the usefulness of the contract in the event of an actual loss (for instance, limits on types of losses

covered and restrictions based upon bank management's action or inaction in managing the

merchant portfolio). In addition, the insurance carrier might not have the financial ability to fund

the contract in the event of significant loss.

Larger merchant processors employ collectors to recover charge-back losses and other fees. A

collector seeks remedy from the principals of the business through negotiations or civil action.

Accounting for Charge-Backs

Management is expected to appropriately detail charge-back losses on Call Reports as other

non-interest expense and reverse any uncollectible fees from income in a timely manner. Any

collected funds are to be reported as other non-interest income.

ACQUIRING RENT-A-BINS

A BIN

18

is a number assigned by an Association to identify the bank for authorization, clearing,

settlement, card issuing, or other processes. Ownership and usage of BINs can result in

significant credit risk exposure if not appropriately controlled, especially when the acquiring bank

owns a BIN and permits other entities to share in the usage, otherwise known as an acquiring

Rent-a-BIN. The concept of Rent-a-BINs (RAB) was introduced earlier in this manual. There are

18

An ICA number, which is similar to a Visa BIN, is assigned by MasterCard. ICAs and BINs are collectively referred to

as BINs in this manual. Examiners may also encounter arrangements with American Express and Discover, particularly

now that their access to banks has expanded.

March 2007 FDIC – Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection 179

Risk Management Examination Manual for Credit Card Activities Chapter XIX

issuing RABs and acquiring RABs. Issuing RABs were the focus of the Credit Card Issuing Rent-

a-BINs chapter while acquiring RABs are discussed here.

Acquiring RABs draw their names from the characteristic of acquiring merchant contracts and

cardholder transactions. Under an acquiring RAB arrangement, an acquiring bank permits

ISO/MSPs to use the bank’s BIN(s) to acquire merchants and settle their credit card transactions.

The ISO/MSP retains the majority of income, and the BIN-owner receives a fee for the use of its

BIN(s). Although it has minimal operational involvement, the BIN-owner has primary

responsibility to the Association if any user fails to perform. The BIN-owner retains the risk of

loss as well as responsibility for settlement with the Associations consistent with the contract

between the bank and the Association. Thus, examiners should insist that management

rigorously oversee and control acquiring RAB arrangements to ensure that the ISO/MSP is

appropriately managing the risks. Oversight controls are important, even if the ISO/MSP shares

liability with the bank. A failure by management to consider any lending relationships the bank

has with ISO/MSPs in analyzing total risk exposure warrants examiner attention. Given the

substantial risk involved, many banks are reluctant to enter into acquiring RAB arrangements.

Risk also exists when an acquiring bank uses a BIN owned by another bank. If the BIN-owning

bank fails to perform, the Associations may hold all of the BIN-users liable. RABs require close

examiner analysis of the acquiring bank’s program to determine the extent of risk to the bank.

THIRD PARTIES

The success of a payment system depends on the credit quality of its participants and its

operational reliability. As mentioned, the presence of third parties coupled with the bank’s ability

to sub-license the entire merchant program, or part thereof, to other entities, introduces

numerous complexities in the transaction and funds flows related to credit card transactions.

Third parties such as ISO/MSPs and servicers are used by acquiring banks for a variety of

functions like soliciting merchants, merchant application processing, charge-back processing,

fraud detection, customer service, accounting services, selling/leasing electronic terminals to

merchants, transaction processing, authorizations, and data capture. Each acquiring bank’s

program is unique regarding the number of third parties used and the services provided.

Examiners should require that banks have proper risk management policies and procedures to

control the applicable third-party risks.

An acquiring bank, as the Association member, is ultimately responsible for the settlement of

transactions processed through its BINs, regardless of the third parties used and the contents of

its contracts with those parties. The acquiring bank (BIN-owner) needs to take an active role in

ensuring the quality and integrity of the services these third parties provide because the quality of

services among third parties varies greatly. Examiners should pay close attention to instances in

which the bank relies on the guarantee of a third party against losses as a substitute for prudent

risk management. Losses associated with high-risk or fraudulent credit card activity can be

substantial and easily reach figures well beyond the means of a seemingly financially capable

third party. Banks have incurred significant losses from failing to control third-party activities.

Uncontrolled growth, fraud, and inadequate operations by the third parties have all resulted in

significant problems for banks. ISO/MSPs in particular could be motivated by their own profits at

the expense of merchant portfolio quality and often have limited financial capacity.

Regardless of the third parties used and any guarantees provided, the examination approach

requires that bank staff have the expertise and knowledge of the business to properly manage

the risks and that management have a sound plan for managing its merchant program as well as

policies and procedures in place to control the risks associated with using third parties and to

properly limit the use of the bank’s BINs by others. For instance, the final review of merchant

applications and the decision to approve or decline a new account should be controlled by the

BIN-owner.

March 2007 FDIC- Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

180

Merchant Processing

The examination should verify that the bank's policies and procedures, in general, provide for:

• A due diligence process to: determine the third party's character and ability to

perform the services; assess the risks associated with using the third party; and

establish risk controls.

• A process for ensuring the adequacy of written agreements.

• A monitoring process for the third party's operations and financial condition.

Examiners should look for evidence that due diligence processes, in general, include:

• Determining that the third party has the operational and financial ability as well as

expertise to perform the services.

• Performing thorough background checks on the third party's principals and key

individuals to determine their good standing, including bank and trade references,

credit reports, and, where appropriate, criminal backgrounds.

• Analyzing the financial capacity of the third party and its principals to determine

continued viability and capacity to absorb losses.

• Performing an on-site inspection.

• Assessing the third party’s marketing practices and the types of merchants targeted.

• Assessing the risks associated with the use of the third party and the controls

needed to manage the risk (for example, underwriting standards, security of sensitive

information, reporting requirements, and procedures for settlement, charge-back

processing, fraud monitoring, and pricing).

• Establishing criteria for requiring additional loss controls, such as reserves or security

deposits to absorb losses stemming from merchant fraud and charge-backs.

• Ensuring separation of duties for activities performed (for example, the individual

conducting the on-site inspection should have no financial interest in its outcome).

• Registering third parties with Associations as required.

The examination should also include assessing whether the bank’s monitoring process, in

general, includes:

• Periodically reviewing the financial condition of third parties and their principals to

determine capacity to meet commitments and remain in good standing.

• Reviewing allowances to ensure they are consistent with the condition of the third

party and volume of business generated.

• Reviewing compliance with the bank’s established requirements (for example,

underwriting standards, settlement and charge-back processing, fraud monitoring,

merchant pricing, and security of cardholder information).

• Periodically conducting on-site inspections.

• Periodically evaluating the third party’s internal controls (for example, through review

of operational audits).

• Assessing system audits for third parties performing processing tasks.

• Periodically reviewing marketing practices.

• Reviewing contingency plans to assure continuity of operations.

• Documenting the bank's relationship with the third party.

• Checking compliance with contractual provisions.

• Determining the adequacy of the bank's controls over third party access to sensitive

information.

March 2007 FDIC – Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection 181

Risk Management Examination Manual for Credit Card Activities Chapter XIX

Contractual Considerations

Concerns arise when management has not obtained a signed, written agreement between it and

each third party or when the agreement fails to take into consideration business requirements,

key risk factors identified during the due diligence process, and the Associations’ regulations.

Legal counsel familiar with merchant processing normally reviews contracts prior to signing.

Contractual considerations generally include:

• Responsibilities of each party.

• Terms specifying compensation, payment arrangements, price changes, and time

frames.

• Provisions prohibiting the third party from assigning the agreement to any other

party.

• Frequency and means of communication and monitoring activities of each party.

• Provisions regarding the ownership, confidentiality, and non-disclosure of cardholder

information as well as compliance with cardholder information security standards.

• Recordkeeping requirements and whether each party has access to these records.

• Responsibility for audits, the bank's access to those audits, and whether the

acquiring bank has the right to perform an audit of the third party.

• Notification requirements of system changes that could affect procedures and

reports.

• Type and frequency of financial information the third party will provide.

• Termination parameters, including potential penalty provisions.

• Maintenance of an adequate contingency plan by the third party.

Additional contractual considerations for ISO/MSPs generally include:

• Tying compensation to the merchant portfolio’s performance (for instance, charge-

back activity).

• Defining responsibilities for fraud and charge-back processing and losses.

• Requiring security deposits from the ISO/MSP, particularly if its financial condition is

weak or the quality of the merchants it solicits presents significant risk.

• Establishing remedies to protect the bank if the ISO/MSP fails to perform (for

example, indemnity provisions, early termination rights, and delayed payment).

• Providing criteria for acceptability of merchants.

• Specifying that the bank owns the merchant relationships.

• Controlling the future use and solicitation of merchants.

• Defining the allowable use of the name and logo of the bank and the ISO/MSP.

• Permitting bank employees to conduct onsite inspections of the ISO/MSP.

• Specifying that all applicable regulations and Association rules are to be followed.

Association Requirements Regarding Third Parties

The bank’s risk management program needs to consider the Associations’ requirements

regarding third parties. Each acquiring bank is expected to register third parties according to the

Associations’ guidelines before accepting services. Associations generally require an initial

registration fee and annual fees for each third party under contract. The fees are normally

passed on to the third party.

The Associations have specific guidelines relating to contract provisions, functions controlled by

the acquiring bank, accessibility of procedural audits, and recordkeeping requirements. In

particular, Association regulations state that:

March 2007 FDIC- Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

182

Merchant Processing

• All new merchant accounts should be reviewed with final approval controlled by the

acquiring bank.

• A registered third party cannot subcontract its bankcard-related services to another

business. Bankcard-related services can only be provided by businesses with a

direct written contract with an Association member.

• All aspects of a member's relationship with a third party should be documented.

• Members are responsible for ensuring that merchants receive payment for the card

transactions deposited.

Even after registration, the acquiring bank remains responsible for ensuring compliance with the

Associations’ operating regulations. The regulations make the acquiring bank liable to the

Associations for the actions of third parties. Banks are to periodically submit certain information

on third parties used to the Associations and can be fined by the Associations for not doing so.

Agent Banks

Agent banks contract with merchants on behalf of an acquiring bank. Agent banks are typically

community banks that want to offer merchant processing services to their merchant customers

but that do not have the management expertise and/or do not want to invest in the infrastructure

needed to serve as an acquiring bank. Acquiring banks generally provide backroom operations

to the agent bank. Depending upon the contractual arrangement, the agent bank may or may not

be liable to the acquiring bank in the event of charge-back or fraud losses. Agent banks with

liability typically perform merchant underwriting. Agent banks without liability are typically called

referral banks. In a referral arrangement, the acquiring bank performs the underwriting, executes

the merchant agreement, and accepts responsibility for merchant losses. Acquiring banks

sometimes compensate the referral bank byway of a referral fee.

If examining an agent bank, examiners should determine whether management fully understands

the bank’s financial liability for charge-backs as well as its responsibilities under the agreement

with the acquiring bank. An agent bank should have appropriate procedures in place to ensure it

fulfills its obligations under such agreement. Examiners should expect that agent banks with

liability have proper risk management policies and controls in place for merchant underwriting

and monitoring, pricing and profitability, and third-party relationships.

Examiners should determine whether management of an agent bank has ensured underwriting

guidelines meet the acquiring bank's underwriting standards, at a minimum, and represent an

appropriate level of risk for the agent bank to hold. Acquiring banks may decline a merchant if it

poses undue risk or does not meet the bank’s minimum standards. Other agent bank tasks

include performing ongoing monitoring of sales, charge-backs, and fraud.

Examiners should look for evidence that pricing of agent relationships is sufficient to cover costs,

including any fees paid to the acquiring bank and anticipated losses. Depending on the size of

the agent bank’s merchant portfolio, separate profitability reports on this business line may not be

necessary. But, that does not negate management’s responsibility to determine if the service is

profitable to the bank. If profits are minimal or nonexistent, considerations would include whether

the risk is sufficiently offset by the intangible benefits gained from offering the services.

Examiners should expect to see a written agreement clearly outlines both agent and acquiring

banks’ responsibilities. They should also determine whether the agent bank has performed

appropriate due diligence regarding the acquiring bank's ability to meet its obligations under the