Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................1

Chapter 2: Canada’s experience with

inflation targeting

..............................................7

Chapter 3: Key challenges for the conduct

of monetary policy

...........................................20

Chapter 4: Lessons from a comparison

of alternative frameworks

....................................33

Chapter 5: Overview of monetary policy tools.............48

Chapter 6: Strengthening the conduct

of monetary policy

............................................65

Monetary Policy

Framework

Renewal

December 2021

Chapter 1: Introduction

Building on success

Every five years, the Bank of Canada and the Government of Canada review

and renew the agreement on Canada’s monetary policy framework. In 2021,

the country’s flexible inflation-targeting framework was renewed for another

five-year period, ending on December 31, 2026.

The Government and the Bank believe that the best contribution of monetary

policy to the well-being of Canadians is to continue to focus on price stability.

The Government and the Bank also agree that monetary policy should

continue to support maximum sustainable employment, recognizing that

maximum sustainable employment is not directly measurable and is

determined largely by non-monetary factors that can change through time.

Further, the Government and the Bank agree that because well-anchored

inflation expectations are critical to achieving both price stability and

maximum sustainable employment, the primary objective of monetary policy

is to maintain low, stable inflation over time.

Under this agreement, the Bank will continue to conduct monetary policy

aimed at keeping inflation—as measured by the 12-month rate of change in

the consumer price index—at 2 percent, with an inflation-control range of

1 to 3 percent.

This agreement also articulates how the Bank can continue to use the

flexibility in its framework to manage the challenges of lower neutral interest

rates globally and uncertainty about maximum sustainable employment. As

such, it provides continuity and clarity and strengthens the framework to

reflect the realities of the world we live in.

Flexible inflation targeting has delivered low, stable and predictable inflation

since it began in 1991. This has contributed to a more stable environment in

which households and firms can make spending and investment decisions. It

has also contributed to sustained growth in output, employment and

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 2

productivity and has improved Canadians’ standard of living. The 2021

reopening of the global economy has been associated with elevated inflation

in Canada and abroad. While this is a global phenomenon, it makes

maintaining a sound framework for monetary policy in Canada all the more

important.

Every time the agreement is renewed, the Bank carefully reassesses whether

the existing monetary policy framework is the best contribution that the Bank

can make to promoting Canada’s economic and financial welfare.

The 2008–09 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic have had a

significant impact on the global economy and financial system, and major

trends such as shifting demographics and new digital technologies are

altering the economic landscape. Climate change and the long-term transition

to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions will drive structural change in the

Canadian and global economies. Also, there is now greater recognition,

supported by economic research, that when the benefits of economic growth

and opportunity are more evenly shared, it leads to more prosperity for the

whole economy.

1

A strong and inclusive labour market helps reduce income

inequality and supports robust demand for goods and services.

Leveraging the flexibility of the framework

These trends emphasize the importance of the flexibility inherent in Canada’s

monetary policy framework. Two of them are particularly relevant:

Neutral interest rates around the world—which ensure that demand is in

line with an economy’s long-run productive capacity—are lower than in

the past and will likely remain low in the future. This means that central

banks will have less room to lower the policy rate in response to negative

shocks. As a result, the Bank will likely have to use other monetary policy

tools more often and may need to hold interest rates low for longer.

Major forces such as shifting demographics, technological change,

globalization and shifts in the nature of work are having profound

effects on the Canadian labour market. This means there is increased

uncertainty about the level of maximum sustainable employment. In other

words, it has become more difficult to pin down the highest level of

1 See, for example, Macklem (2021) as well as Hsieh et al. (2019) and Ostry et al. (2018).

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 3

employment that the economy can sustain before inflation pressures

build.

To manage these challenges, the Bank will continue to leverage the flexibility

inherent in its framework. Specifically, when conditions warrant, the Bank will:

use a broad set of monetary policy tools, as well as the 1 to 3 percent

inflation-control range, to deal with the likelihood that the Bank’s policy

rate will be at its lowest possible level more often.

actively seek the level of maximum employment needed to sustainably

achieve the inflation target. The Bank will consider a broad set of

indicators to gauge the health of the labour market and to inform its

assessment of the economic outlook.

The Bank will use the flexibility of the 1 to 3 percent range only to an extent

that is consistent with keeping medium-term inflation expectations well

anchored at 2 percent. And the Bank will clearly explain when it is using that

flexibility.

The Bank will continue to assess financial system vulnerabilities, recognizing

that a low interest rate environment can be more prone to the development

of financial imbalances. A variety of other policy instruments, such as

macroprudential tools, are better suited than monetary policy to address

these vulnerabilities. But because monetary policy can exacerbate financial

vulnerabilities, the Bank will continue to be mindful of the risk that such

vulnerabilities can lead to worse economic outcomes down the road.

Climate change poses substantial risks to the global and Canadian economies.

While monetary policy cannot directly tackle the threats posed by climate

change, the Bank will develop the modelling tools needed to take into

account the important implications of climate change on the Canadian

economy and financial system.

Conducting a more in-depth and comprehensive

review

Past reviews of the inflation-control target agreement have included serious

consideration of some alternative frameworks. However, the Bank has not

performed a systematic comparison of a full range of alternatives since it

adopted inflation targeting. For this latest review and renewal, the Bank used

a combination of model simulations, lab experiments and public consultations

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 4

to run a “horse race” of key alternatives to inflation targeting, weighing the

pros and cons of each:

average inflation targeting

a dual mandate, targeting both inflation and employment

nominal gross domestic product (NGDP)—both level and growth—

targeting

price-level targeting

In this horse race, the current flexible inflation-targeting framework, along

with average inflation targeting and a dual mandate, did better than other

approaches that represent larger departures from the status quo. While

neither average inflation targeting nor a dual mandate was judged to be

better overall than the current approach, the Bank found value in some

elements of each of these two alternatives. The Bank’s research concluded

that the inflation-targeting framework is flexible enough to mimic these key

elements without the drawbacks associated with the alternative approaches.

Listening to Canadians

The Bank also significantly expanded its outreach activities to include public

consultations with Canadians and discussions with a broader set of

stakeholders and interest groups. Since the 2008–09 global financial crisis,

central banks have implemented extraordinary policies and used a variety of

new tools—putting central banks in the public eye more than ever. The Bank’s

recent public outreach was an important opportunity to assess the economic

environment, gather input and ensure that the Bank’s policies and decisions

reflect the views of the people it serves. This, in turn, reinforces public trust. As

well, gathering a more diverse range of views on the Bank’s activities,

decisions and frameworks—and on alternatives—ultimately leads to better

policy outcomes.

Through these consultations, which took place in 2019 and 2020, the Bank

aimed to:

gain a better understanding of the concerns Canadians have about the

economy and economic policy

learn how the existing framework affects different groups of Canadians

and how the alternative approaches might affect those groups

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 5

assess how well people understand the different monetary policy

frameworks and their trade-offs, since these frameworks are more

effective if Canadians understand them well

gauge people’s awareness, understanding of and support for

unconventional policy tools such as forward guidance and quantitative

easing

The consultations and subsequent public opinion research demonstrated that

Canadians are broadly confident in the Bank’s ability to keep inflation low and

stable, and that public trust in the Bank and the financial system would

remain steady through the COVID-19 pandemic. Continued engagement and

clear communications with Canadians will be required as the Bank navigates a

period of above-target inflation as a result of the unique characteristics of the

economic reopening and recovery from the pandemic.

Many Canadians were open to some change in the Bank’s approach but

generally supported the continued use of inflation targeting. Most viewed the

current inflation-targeting framework as balanced, flexible and the most easily

understood approach. Of the alternatives, a dual mandate received some

interest—reflecting a desire by many Canadians for the Bank to consider how

it could support the labour market—but many questioned whether an

employment target would be achievable. Canadians also indicated an interest

in average inflation targeting, which suggests a desire for more flexibility in

how the Bank achieves the 2 percent target. The other frameworks—price-

level targeting and NGDP targeting—were seen as less achievable or harder

to understand.

The majority of participants emphasized the importance of the Bank being

flexible in how it achieves the inflation target. Specifically, Canadians were

most comfortable with an approach that targets a range for inflation and

adjusts interest rates slowly to achieve the target. Many were open to

accepting longer periods of above- or below-target inflation to support the

economy and jobs.

Outlining the road to renewal

This background document describes the research and analysis that

supported the new agreement on Canada’s monetary policy framework.

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 6

Chapter 2 discusses Canada’s experience with inflation targeting. Chapter 3

explores the key challenges in conducting monetary policy given the shifts in

the economic landscape. Chapter 4 provides a detailed discussion of the

Bank’s comparison of alternative policy frameworks. Chapter 5 examines the

full range of monetary policy tools available in the Bank’s tool kit. Finally,

Chapter 6 outlines how the Bank will conduct monetary policy under the

renewed agreement.

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 7

Chapter 2: Canada’s experience

with inflation targeting

Over the past 100 years, Canada has used several monetary frameworks.

These have included the gold standard, the Bretton Woods system of pegged

exchange rates, monetary targets and, since the early 1990s, inflation

targeting.

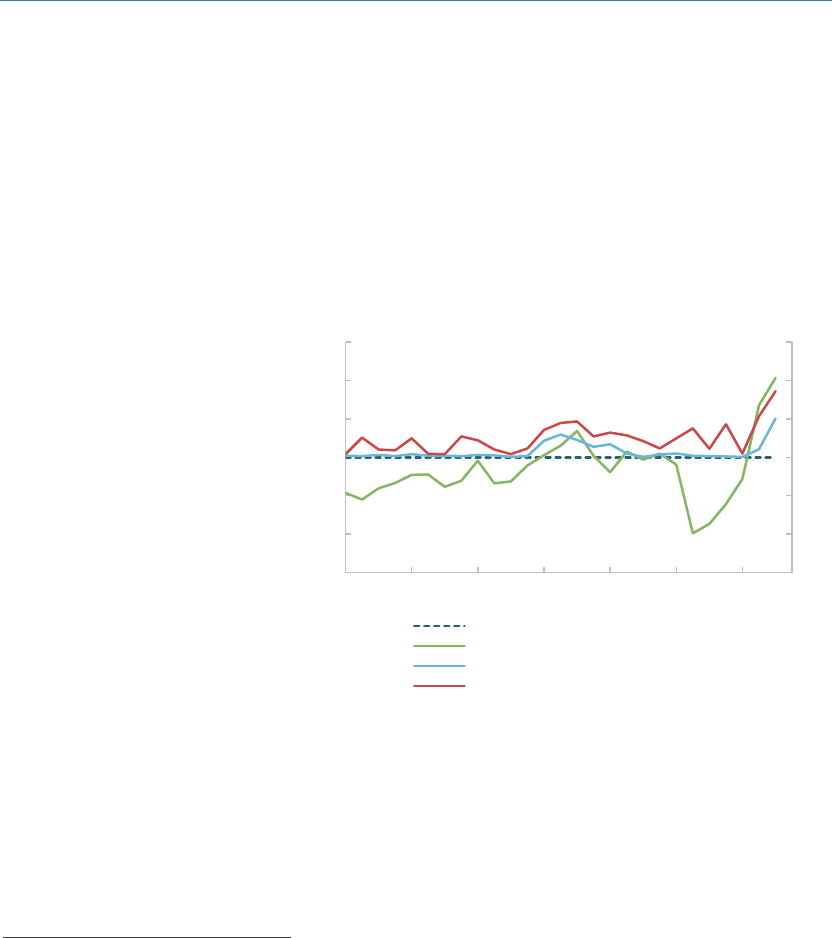

Canada first announced an inflation target in February 1991. After the target’s

introduction, inflation, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI), came

down quickly, and since the late 1990s it has generally been low, stable and

predictable (Chart 1). This stands in sharp contrast to the high inflation of the

1970s and early 1980s.

Inflation spent periods below the 2 percent target during the 2008–09 global

financial crisis and the 2014–15 collapse in commodity prices and, in 2020–21,

during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, average inflation following the

global financial crisis up until the pandemic was below 2 percent.

The COVID-19 shock presented unique challenges for monetary policy. The

widespread closure of many sectors of the economy was met with aggressive

fiscal and monetary policy stimulus. This stimulus supported a faster, albeit

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

1915 1925 1935 1945 1955 1965 1975 1985 1995 2005 2015

%

Inflation-control range CPI inflation Inflation target

Chart 1:

Introducing inflation targets brought inflation down

12

-month rate of increase, monthly data

Last observation: October 2021

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada calculations

Inflation

targeting

Monetary target and

other frameworks

Gold standard

framework

Bretton Woods

system

Bank begins

operations

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 8

uneven, recovery. The strong global recovery, particularly in the demand

for goods, exacerbated supply constraints and higher energy prices. This

led to an average inflation rate of goods in the first 11 months of 2021 of

4.4 percent, well above that of services at 2.1 percent. This contrasts

sharply with recent trends: over the 20 years before the pandemic, goods

inflation averaged only 1.4 percent while inflation for services was 2.4

percent. This rapid rise in inflation for goods was the key driver in above-

target inflation during 2021.

2

Notwithstanding periodic macroeconomic shocks such as the one Canadians

are experiencing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada’s flexible

inflation-targeting framework has kept inflation low, stable and predictable

for three decades. It has been robust to a variety of economic circumstances

and has enhanced welfare by fostering a more certain environment where

planning for the future is easier.

Three key factors have contributed to the framework’s success (Carter,

Mendes and Schembri 2018):

The inflation target is straightforward to explain and understand. This has

improved accountability and allowed consistent application of the

framework over time.

The framework is based on an agreement between the Bank of Canada and

the Government of Canada. The joint agreement grants the Bank operational

independence to achieve the inflation target, while emphasizing that inflation

control ultimately remains a shared commitment of both parties. The

agreement also gives the target democratic legitimacy, further enhancing the

target’s credibility and helping to anchor inflation expectations.

The regular, formal and transparent review and renewal process leads to

continual improvement of the framework and its implementation. This

process allows the Bank to incorporate lessons learned from historical

experience and research.

Each renewal cycle has involved analysis of a range of issues. For instance,

during the 2016 cycle, the Bank focused its review and research on the

following three questions:

Should the 2 percent inflation target be increased?

2

Gravelle (2021b) offers a discussion on the role of energy prices, shifts in demand across goods and supply

constraints on consumer prices over 2021.

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 9

To what extent should the conduct of monetary policy consider financial

stability?

How should core inflation be measured and used as an operational guide

for the conduct of monetary policy? (Box 1 presents an updated

assessment of the core measures.)

Box 1:

An updated assessment of the core measures

The inflation target in Canada is expressed in terms of consumer price index (CPI)

inflation. Monetary policy achieves the inflation target by influencing domestic

demand for goods and services, which, in turn, affects underlying inflationary

pressures. Many other factors can also influence CPI inflation—for example, changes

in the prices of commodities, which are set in global markets. Because the price

movements are likely to be short-lived and the effects of monetary policy on inflation

are delayed, the Bank of Canada focuses on the underlying rate when making policy

decisions. It also uses forecasts for CPI inflation that go beyond the horizon of the

temporary factors.

For the 2016 renewal of the

inflation-control agreement,

the Bank replaced CPIX

inflation as its preferred

measure of core inflation.

3

It

adopted three other measures

that performed well across a

range of evaluation criteria—

CPI-common, CPI-trim and

CPI-median (Chart 1-A).

4

Using these three indicators of

inflation over the past five

years has helped the Bank

manage the risks associated

with relying on any single

indicator.

3 CPIX inflation excluded eight of the most volatile components of the CPI (fruit, vegetables, gasoline, fuel oil,

natural gas, mortgage interest, intercity transportation and tobacco products) and adjusted the remainder for the

effect of changes in indirect taxes.

4 CPI-common uses a statistical procedure to track common price changes across categories in the CPI basket. CPI-

trim excludes upside and downside outliers. CPI-median is the median inflation rate across CPI components. For

details, see Bank of Canada (2016) and Khan, Morel and Sabourin (2015).

0

1

2

3

4

5

1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

%

CPI-common CPI-trim CPI-median

Chart 1-A: Measures of core inflation have

provided a useful guide for monetary policy

Year-over-year percentage change, monthly data

Last observation: October 2021

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank

of Canada calculations

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 10

From 2017 through 2019, the dynamics of all three measures were consistent with an

economy where slack had largely been absorbed—all were within a narrow range

and close to 2 percent. The use of these measures as a guide for monetary policy was

tested more recently because of the uneven economic impacts of the pandemic. The

three core inflation measures provided useful insights into underlying inflation given

the unique shifts in demand and supply and the resulting price movements caused

by the pandemic. For example, CPI-common initially fell, reflecting the large amount

of excess capacity in the economy. However, CPI-median and CPI-trim filtered out

most of the weakness in inflation in some hard-to-distance service sectors. As supply

disruptions became prevalent in 2021, CPI-trim and CPI-median increased, reflecting

the inflationary pressures from components experiencing supply constraints.

Consequently, the range between the three measures widened further—highlighting

the value of looking at more than one measure of underlying inflation.

5

An updated evaluation of the statistical properties of the core measures confirms

that no single measure dominates—each has strengths and limitations (Table 1-A).

6

Still, the three measures are more useful than others because they effectively capture

persistent movements in inflation and they tend to move with the macroeconomic

variables that monetary policy affects. The current measures also remain less biased

and less volatile than other measures.

While the core measures have helped guide monetary policy, core inflation is just

one of many inputs in the process. It is important to consider the three measures

together with a detailed analysis of the determinants of inflation and broader

measures of capacity pressures. These measures include, but are not limited to,

labour market indicators, wages and other input costs such as commodity prices,

estimates of the output gap, and business and consumer survey results.

Table 1-A: Summary of an evaluation of different core inflation measures

CPI-common

CPI-median

CPI-trim

Unbiased

✔

✔

✔

Persistent

✔

✔

Volatile

✔

✔

Moves with output gap

✔

✔

✔

Looks through sector-specific shocks

✔

Has an easily understood methodology

✘

✔

Top performance

✔

Favourable performance

Neutral performance

✘

Unfavourable performance

5 See Bank of Canada (2021a) for a discussion of the movements in core inflation measures during the pandemic.

6 For details, see Lao and Steyn (2019).

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 11

The current review of the inflation-control target builds on the work done in

previous renewal cycles.

Inflation targeting has not only consistently delivered low and stable inflation

but also enhanced the resilience of the economy to external shocks, thereby

reducing volatility and improving overall economic performance.

7

For

example, real economic growth has been much steadier than it was before

the adoption of inflation targeting (as shown by a declining standard

deviation in Table 1). Nominal interest rates have also been lower and more

stable. This is mainly because inflation expectations have declined, but also

because the premiums to compensate investors for inflation risk have, on

average, been smaller.

Overall, the stability in inflation over the past 30 years has increased the

credibility of monetary policy and led to well-anchored inflation expectations.

7 The inflation-targeting regime has contributed to Canada’s improved economic performance for the past 30 years.

It has allowed Canadian businesses and households to read price signals more clearly, to respond to relative price

shocks more promptly and generally to allocate resources more efficiently. Canada’s flexible exchange rate has

complemented the monetary policy framework, facilitating economic adjustment to various internal and external

shocks. Many other factors have also helped improve Canada’s economic performance; these include the

entrenchment of sound fiscal policy, rigorous prudential regulation and supervision, and structural reforms.

Table 1: Canada’s economic performance before and after inflation targeting

Average (percent)

Standard deviation

October 2016 to

October 2021

October 2016 to

October 2021

Jan 1975

to Jan 1991

Feb 1991

to Sept 2016

Oct 2016 to

Dec 2019

Oct 2016 to

Oct 2021

Jan 1975

to Jan 1991

Feb 1991

to Sept 2016

Oct 2016 to

Dec 2019

Oct 2016 to

Oct 2021

CPI: 12-month increase

7.1

1.9

1.9

1.9

2.9

1.1

0.4

1.0

Real GDP growth*

2.8

2.4

2.5

2.2

3.8

2.6

1.3

13.2

Unemployment rate†

8.9

8.0

6.1

7.0

1.7

1.5

0.4

1.9

3-month interest rate‡

10.8

3.5

1.6

1.2

3.0

2.2

0.4

0.7

10-year interest rate§

10.7

4.9

1.9

1.5

2.0

2.2

0.4

0.6

Months in inflation-

control range (percent)

0.0 72.7 100.0 72.1

* This is the annualized quarter-over-quarter growth rate for quarters within the time period. The table incorporates real GDP data

through the third quarter of 2021.

† Unemployment data start in January 1976 with the introduction of a new labour force survey.

‡ The 3-month interest rate refers to the 3-month bankers’ acceptance rate.

§

Due to data availability before June 1982, the 10-year interest rate refers to the yield of government bonds with maturations

longer than 10 years; after June 1982, it is based on the 10-year government bond yield from Statistics Canada.

Sources: Statistics Canada, Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada and Bank of Canada calculations

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 12

Public perceptions of current inflation, however, are often higher than

measured inflation (Box 2). Nevertheless, the clarity and simplicity of the

inflation target enhanced the credibility and the general effectiveness of

monetary policy. Furthermore, the target made it easier for the public to hold

the Bank accountable for its performance. Through the years, the Bank has

sought to become more transparent in explaining its conduct of monetary

policy (see Box 10 in Chapter 6).

Box 2:

Differences between perceived and actual inflation

Survey data in several countries, including Canada, point to a gap between measured

and perceived inflation. This could raise concerns that the consumer price index (CPI)

does not accurately reflect inflation as experienced by many Canadians. Large

differences between perceived and actual inflation could eventually undermine the

legitimacy of the inflation-control framework.

The Bank of Canada held

consultations with Canadians

and studied possible

explanations for the

perception-measurement gap.

Responses to the Bank’s

Canadian Survey of Consumer

Expectations (CSCE) reveal the

gap between measures and

perceived inflation in Canada

(Gosselin and Khan 2015).

Households, on average, tend

to believe inflation is higher

than actual CPI inflation as

measured by Statistics Canada

(Chart 2-A). Still, current

perceptions of inflation have

been anchored firmly near the target. Consumer expectations of future inflation tend

to be above the target and vary more than perceptions of current inflation.

8

8 There is also evidence of some backward-looking expectations, as those who expect high inflation in the future

tend to perceive high inflation today.

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

%

Bank of Canada inflation-control target

Official CPI

Current perceptions of inflation

One-year-ahead inflation expectations

Chart 2-A: Households' perceptions of inflation tend

to be higher than official measures

Year-over-year percentage change, quarterly data

Last observation: 2021Q3

Sources: Statistics Canada, Bank of Canada and

Bank of Canada calculations

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 13

Several factors can drive the perception-measurement gap (the difference between

the blue and green lines in Chart 2-A).

First, the CPI basket does not represent the spending habits of all individual

households. While the CPI measures the change in prices of goods and services

purchased by the average household, each household purchases different

proportions of the items in the CPI basket and experiences inflation somewhat

differently. In the Bank’s public consultations, participants said that in their view the

CPI does not effectively capture the rising costs of certain goods and services—for

example, the high cost of food in remote communities, education costs or the

growth in housing prices across the country. To assess the importance of these

differences, the Bank and Statistics Canada analyzed how the weights in the CPI

basket could be adjusted to better represent the spending patterns of different

demographic groups.

9

Results show that, on average, inflation rates based on

spending baskets for different cohorts are relatively similar to official CPI inflation.

A second factor driving the perception-measurement gap relates to the concept of

quality adjustment. Essentially, adjustments are made in the CPI to capture changes in

the quality of products as new models or varieties are introduced. But consumers often

do not recognize how much a product is improving over time and may focus on its

rising price rather than its higher value. This phenomenon is particularly important for

products with high rates of technological advancement. Without quality adjustments,

CPI inflation would be only about 0.2 percentage points higher on average, which

would explain just a small portion of the perception-measurement gap.

A third factor driving differences between perceived and actual inflation relates to

housing. Participants in public consultations highlighted the growth in house prices

as key to why they feel inflation is higher than 2 percent. Households usually

consider housing costs to be the acquisition cost. However, in the CPI, housing is

closer to a cost-of-living concept, measured as the imputed cost of services provided

by housing.

10

In recent years, the growth in house prices has tended to be much

greater than the increase in housing costs as measured by the CPI. This difference

can explain about 0.3 percentage points of the gap between actual and perceived

inflation.

Overall, the measurement issues reviewed seem to explain less than half of the

perception-measurement gap. Other behavioural factors might also be at play. For

instance, the loss of purchasing power as a result of significant price increases has

been found to have an outsized psychological impact. To test this, an alternative CPI

9 See Keshishbanoosy et al. (forthcoming).

10 The cost of housing includes all required expenses linked to living in and owning a house, including mortgage

interest costs, home-insurance premiums, maintenance and repairs, and replacement costs. See Sabourin and

Duguay (2015).

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 14

inflation was calculated by trimming 20 percent of price declines and 10 percent of

price increases. Households’ expectations were found to be close to this alternative

measure of inflation, suggesting that consumers give more weight to price increases

and that excluding large declines could explain a significant part (0.7 percentage

points) of the gap between actual and perceived inflation.

11

An important explanation of Canadians’ elevated views of inflation could be

information gaps. When information about prices is not readily available or is too

costly to acquire, people rely on their own experiences to form expectations. Central

banks can help fill the information gaps by making information more readily

available and supporting economic literacy. Bank analysis shows that individuals

update their views on inflation when they receive new information, particularly

information about the Bank’s inflation target and about inflation forecasts.

12

Knowledge is also key: the inflation expectations of people with higher financial and

economic literacy are more in line with measured inflation. For instance, in the CSCE

results, the perception-measurement gap is largest for respondents with low levels of

education and income. In this context, new communication strategies to reach a

broader audience and increase financial and economic literacy are worth exploring.

The Bank’s The Economy, Plain and Simple series and the Bank of Canada Museum’s

education programs are steps in that direction.

Large external shocks over the years (such as the global financial crisis and the

COVID-19 pandemic) have led the Bank to use different tools within its

inflation-targeting framework. These have included, for example, forward

guidance and quantitative easing. However, inflation targeting as a framework

has endured, both in Canada and in many countries (Rose 2020). Although

economies faced different experiences during these shocks, no inflation-

targeting central bank moved away from having a clear inflation objective.

11 Perceptions of inflation also appear to be partly determined by a consumer’s own view of the costs of a small set

of products and services, which constantly increase; these include food prices, the cost of renting and house prices

(see Keshishbanoosy et al., forthcoming). However, while studies in other countries have found that recent

shopping experiences and frequent purchases such as gasoline and food may affect households’ overall inflation

expectations, Keshishbanoosy et al. calculate Canadian CPI inflation for frequent purchases and find little

difference over the past five years between the inflation rates of frequent purchases and that of the all-items CPI.

12 For details, see Kostyshyna and Petersen (forthcoming).

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 15

Low inflation and maximum sustainable

employment

In essence, inflation targeting is about achieving low inflation together with

maximum employment because, to sustainably achieve either, the economy

needs both. Without maximum sustainable employment, the shortfall in jobs

and incomes will pull inflation below target. And without inflation near its

target and well-anchored inflation expectations, the economy would be less

resilient to various shocks, leading to large fluctuations in employment.

Since maximum employment is not directly observable, and in practice it is

hard to gauge when reached, a range of indicators should be examined to

assess the health of the labour market.

The most common measure of the state of the labour market is the

unemployment rate, which is defined as the percentage of the labour force

that does not have a job and is actively looking for work.

13

Before the

COVID-19 pandemic, the unemployment rate was close to a historic low due

to strong gains in full-time jobs in the service sector (Chart 2, panel a).

13 The labour force is the total number of employed and unemployed in the economy.

Chart 2: Before the pandemic, the unemployment rate was close to a historic

low and the employment rate was rising

Monthly data

Last observation: October 2021

Source: Statistics Canada

4

8

12

16

1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

%

a. Unemployment rate

50

55

60

65

1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

%

b. Employment rate

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 16

A broader measure of labour market health is the employment rate, which is

the number of employed people as a share of the working-age population.

The maximum sustainable employment rate is determined largely by

structural factors beyond the control of monetary policy. For example, the

employment rate has risen over time (Chart 2, panel b). This is mostly due to

increases in the employment rate for women until the early 2000s. That said,

the inflation-targeting framework has contributed to reducing employment

fluctuations by stabilizing overall demand.

More recently, the pandemic had a large and uneven impact on the labour

market. The effects were more severe for certain sectors and their workers.

Hard-to-distance service industries—where physical distancing is either

difficult or impossible—suffered the most. Meanwhile, industries where

physical distancing or remote work is possible—such as professional services,

finance and public administration—were better able to adapt. These

differences across sectors led to unequal consequences. Low-wage workers,

women and young people were most affected.

Using flexibility

The Bank strives to make forward-looking policy decisions based on several

important considerations, drawing from a wide range of information. To

achieve this, the Bank has introduced a degree of flexibility into the practice

of monetary policy with an inflation target. At times this has led to the use of

different horizons to bring inflation back to target.

A key feature of the current policy framework is a risk management approach

that allows policy-makers to weigh multiple factors and risks during policy

deliberations. These include the risk of having the policy rate constrained by

the effective lower bound (ELB), other forecast risks, employment

considerations and financial stability concerns (Poloz 2020).

14

The Bank uses

a variety of models, data analysis, survey evidence and judgment to inform its

understanding of these factors and risks and how they might interact and

affect its ability to control inflation. The flexibility in the inflation-targeting

14 Kozicki and Vardy (2017) describe the uncertainties that central banks face. For instance, uncertainty is inherent

in measuring economic data and in unobserved metrics. Uncertainty is also linked to the models that are used to

inform policy decisions. And unforeseen developments are always possible.

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 17

framework has allowed for adjustments in the expected time horizon for

bringing inflation back to target.

15

Other complementary policies could also help manage the trade-offs faced by

inflation-targeting central banks (Box 3). For example, automatic fiscal

stabilizers that increase spending during economic downturns can also help

monetary policy achieve the inflation objective and stabilize the economy

(MacKay and Reis 2016; Meh and Poloz 2018).

Box 3:

How monetary and fiscal policy can work together

Recent years have seen a revival of research into monetary and fiscal policies and

how they can reduce fluctuations in the business cycle and increase resilience to

external shocks. The 2008–09 global financial crisis showed that monetary policy

alone may be not be enough to lessen the negative effects of large shocks, especially

certain types. One implication is that the benefits of using both monetary and fiscal

policies to lean against big shocks may be greater than previously thought.

16

Monetary policy can generally react quickly to unanticipated changes in economic

conditions by changing the short-term interest rate, although its full impact on the

economy can take time. Changes to the short-term interest rate affect all firms and

households regardless of their exposure to a shock. Fiscal policy, in contrast, can

more easily target specific groups or sectors through transfer programs that are

quick to implement, which is helpful when shocks affect firms or individuals

differently. This has led some to argue in favour of a complementary approach,

where both monetary and fiscal policies are used to moderate the effects of shocks.

Fiscal policy can contribute to macroeconomic stability through three main policy

tools:

Automatic fiscal stabilizers, such as employment insurance or progressive

personal income taxes, can help stabilize business-cycle fluctuations. They do this

by reducing swings in individuals’ disposable income and redistributing resources

from individuals with higher income to those with lower income. However, the

impact of some automatic stabilizers may be less because they can distort labour

15 See Bank of Canada, “Bank of Canada Releases Background Information on Renewal of the Inflation-Control

Target,” press release (November 9, 2011).

16 Dong et al. (2021) review the recent literature on the complementarities between fiscal policy and monetary

policy for stabilizing economic activity.

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 18

market behaviour.

17

Because many automatic stabilizers have multiple policy

objectives, how best to design them is an open question.

Changes to public spending and tax instruments can be designed to offset

business-cycle fluctuations by supporting aggregate demand. Some discretiona

ry

f

iscal expenditures have short-term multipliers that are close to or above one

,

w

hich means that each additional dollar of expenditure translates into close to an

additional dollar of output. When interest rates are near the ELB, fiscal stimulus

ha

s a larger impact. While discretionary spending can focus on the specific policy

priorities that are most relevant at the time, they may require legislation an

d

some ca

n take time to implement.

Government credit programs extend credit to certain borrowers and

market segments and can implicitly or explicitly guarantee obligations of

government-sponsored enterprises. These credit policies can mitigate economi

c

downturns that are exacerbated by severe financial market distress.

The policy responses to the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic illustrate

how both fiscal and monetary authorities can respond rapidly to large shocks. The

responses to COVID-19 included unprecedented fiscal actions in some countries,

with large-scale programs introduced quickly to offset the sudden loss of income

that some households and firms experienced. While some fiscal policies were

targeted at the most affected households and firms, others were broader-based and

relied on existing transfer and tax systems—in some cases because new programs

take time to implement. Recent research examines the economic impact of various

elements of the fiscal response to the pandemic. For example, MacGee, Pugh and

See (2021) examine how the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) affected

household savings and debt, and Petit and Tedds (2020) highlight differences in how

Canadian provincial and territorial governments treated CERB payments in assessing

eligibility for income assistance programs.

18

During the pandemic, flexibility was exercised through an aggressive

monetary policy response. The Bank quickly reduced the policy rate to its ELB,

provided forward guidance and used additional tools such as quantitative

17 A variation suggested in the academic literature is a pre-committed fiscal spending formula that would be

triggered by certain macroeconomic conditions. Such a state-contingent, non-discretionary fiscal policy would

have the advantage of being timely and easy to communicate. But identifying appropriate and robust triggers and

sorting out how to develop credibility around the commitments could be challenging.

18 A growing literature examines programs introduced in other countries. For example, Autor et al. (2020) and

Chetty et al. (2020) examine the Paycheck Protection Program (part of the US Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and

Economic Security Act), while Romer (2021) asks whether aspects of the US fiscal response, such as one-time

stimulus payments, were well targeted.

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 19

easing to support financial market functioning and reinforce the forward

guidance. The forward guidance demonstrated that even without room to cut

the policy rate further, the Bank can still provide monetary stimulus by making

a commitment to hold the policy rate at its ELB for longer than the degree of

excess capacity might suggest. Given the lags involved in the transmission of

monetary policy, the Bank’s response resulted in a projection for inflation that

temporarily exceeded 2 percent. Nevertheless, the public could be confident

that the Bank would remain focused on the inflation-control mandate even

while pursuing aggressive monetary policy to support a stronger, broader-

based recovery (see Box 8 in Chapter 5).

To maintain its credibility and enhance the public’s trust throughout the

pandemic, the Bank also committed to being transparent about the

parameters of its asset purchase programs and to reporting regularly on the

evolution of the its balance sheet. The Bank’s credibility and independence

were evident in market perceptions following Bank actions. For instance,

market expectations for policy rates generally tracked the Bank’s forward

guidance.

19

In addition, inflation expectations stabilized—allowing reductions

in the policy rate to be more fully passed through to real borrowing costs.

20

The results of the Bank’s consultations show that Canadians’ trust in the Bank

held firm or increased slightly during the pandemic and that people are highly

confident the Bank can continue to achieve its inflation target (Bank of

Canada 2021b).

19 The Bank’s commitment in July 2020 to leave the policy rate at the ELB was contingent on achieving the inflation

target on a sustainable basis. Following that announcement, market expectations for the policy rate flattened. In

October, the Bank reinforced its commitment and specified that it did not expect to sustainably meet the inflation

objective until some time in 2023. This updated forecast was credible because market pricing after the October

announcement had the policy rate at the ELB until at least 2023. As the outlook brightened in late 2020, market

pricing beyond 2022–23 moved slightly higher. But short-term yields remained anchored by the forward guidance.

In October 2021, the Bank’s projection was updated as the recovery progressed. The commitment to hold the

policy rate at the ELB until economic slack is absorbed so that the 2 percent inflation target is sustainably achieved

was then revised to sometime in the middle quarters of 2022.

20 Professional forecasters’ long-term inflation expectations remain firmly anchored at 2 percent, while consumer

expectations in the Canadian Survey of Consumer Expectations and business expectations in the Business Outlook

Survey have bounced back relative to their 2020 levels. Market-based measures of expectations fell at the start of

the crisis, recovered as the Bank rolled out its quantitative easing program, and ticked up with the Bank’s decision

in July 2020 to commit to holding the policy rate steady until the inflation objective is sustainably achieved.

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 20

Chapter 3: Key challenges for the

conduct of monetary policy

Over the past decade or so, several economic trends have accelerated,

affecting the Canadian economy. The 2008–09 global financial crisis and the

COVID-19 pandemic have had significant impacts on the global economy and

financial system. And forces such as demographic shifts, globalization, new

digital technologies and climate change are affecting the economic

landscape.

These economic and social trends raise two key challenges for the conduct of

monetary policy:

The persistence of low interest rates since the global financial crisis has led

to a growing consensus that low neutral rates are likely to continue for

some time, constraining central banks’ ability to provide stimulus through

reductions in their policy rate.

Major forces have increased uncertainty and made it harder to pin down

the maximum level of employment that the economy can sustain before

inflationary pressures build.

In addition, when conducting monetary policy, central banks need to consider

the historically high levels of debt held by households and businesses.

Despite significant advances in prudential financial regulations, particularly

with respect to housing finance, a prolonged period of low interest rates

could contribute to a buildup of financial vulnerabilities. Thus, while a number

of prudential, macroprudential and housing policy instruments are better

suited than monetary policy to address financial vulnerabilities, the possibility

that monetary policy could exacerbate these vulnerabilities remains an

important consideration.

A world of low neutral interest rates

The low interest rates observed in advanced economies since the global

financial crisis partly reflect low neutral rates, which many agree are likely to

persist in the coming years (e.g., Del Negro et al. 2019). This persistence

means central banks will have less room to lower their policy rates before

hitting the effective lower bound (ELB). As a result, ELB episodes are more

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 21

likely to occur in the future than they were during the first two decades of

inflation targeting. Given the tendency for inflation to be below target during

ELB episodes, more frequent ELB episodes may make it difficult for the Bank

of Canada to achieve its inflation target of 2 percent.

To assess the likelihood of an ELB episode, we use the concept of the neutral

rate of interest. The neutral rate is defined as the policy rate that coincides

with output at potential and inflation equal to target after the effects of

cyclical shocks have dissipated. Although estimates vary across countries and

time periods, most agree that the neutral rate of interest has declined in

advanced economies since at least the early 2000s and is likely to remain near

its historical lows over the coming years.

21

In Canada, both the actual policy rate and the estimated neutral rate have

declined since the early 2000s (Chart 3). In the mid-2000s, the Bank assumed

a nominal neutral rate of roughly 5 percent. Since the global financial crisis,

estimates have shifted downward, and the 2021 Canadian nominal neutral

rate estimate is in the range of 1.75 to 2.75 percent, with a midpoint of

2.25 percent (Brouillette et al. 2021).

21 See, for example, Laubach and Williams (2003), Del Negro et al. (2019) and Feunou and Fontaine (forthcoming).

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

1991 1996 2001 2006 2011 2016 2021

Effective lower bound (+25 basis points) Policy rate Estimated neutral rate

Note: The grey range is the estimated range of the neutral rate, and the black line is the mid point of the range.

Source: Bank of Canada

%

Last observation: October 2021

Chart 3: The Bank of Canada policy rate and the estimated neutral rate

have declined

Monthly

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 22

This decline in the neutral rate makes it more likely that monetary policy will

reach its ELB in future economic downturns. With a lower neutral rate, central

banks have less room to reduce the policy rate in response to negative shocks

before reaching the ELB. Staff estimate that the likelihood that adverse

economic shocks will result in the policy rate hitting its stated ELB of

0.25 percent has increased from 6 percent in 2016 to about 17 percent in

2021 (Chart 4, panel a).

22

The lower neutral rate has also extended the

projected average duration of ELB episodes from 2.3 quarters in 2016 to

about 7 quarters in 2021 (Chart 4, panel b).

The recent experience with the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates the

implications of ELB episodes for inflation (see Chapter 2). Even with a rapid

decrease of the policy rate to the ELB in response to weak aggregate demand,

inflation fell well below the 2 percent target. This is consistent with analysis

that ELB episodes often see inflation below target.

The risk of frequent and prolonged ELB episodes where inflation is

persistently below target has raised concerns that inflation, over the medium

term, may average below 2 percent. If inflation were to average below target

for a prolonged period, households and firms could adjust their inflation

expectations downward. This would cause the ELB to become even more of a

22 Staff used the Bank’s main dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model, the Terms-of-Trade Economic Model

(ToTEM) III, for this analysis. See Corrigan et al. (2021) for details on ToTEM III.

data

Chart 4: The probability of being constrained by the effective lower bound on

the policy interest rate has increased

Note: In both panels, the 2021 real neutral rate is 0.25 percent, the 2016 real neutral rate is 1.25 percent and the real neutral rate before

the global financial crisis is 3 percent. Rates are calculated using the Bank of Canada’s Terms

-of-Trade Economic Model (ToTEM) III.

Source: Bank of Canada

0

2

4

6

8

2021 real neutral

rate

2016 real neutral

rate

Real neutral rate

before global

financial crisis

Quarters

b. Average duration of effective lower bound episodes

0

5

10

15

20

2021 real neutral

rate

2016 real neutral

rate

Real neutral rate

before global

financial crisis

%

a. Relative frequency of a binding effective

lower bound

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 23

constraint because it would be more difficult to reduce the real policy rate. As

a result, central banks need to adjust how they conduct monetary policy.

Changes could include using a larger suite of monetary policy tools and

approaches more often. This would better mitigate the impacts of ELB

episodes on employment and output and help avoid inflation remaining

below 2 percent for extended periods of time (see Chapter 5).

Increased uncertainty about the level of maximum

sustainable employment

Major forces, including demographic changes, technological advancements,

globalization and shifts in the nature of work, have had profound effects on

the Canadian labour market. These evolving forces have increased uncertainty

around assessments of the level of maximum sustainable employment—the

highest level of employment that the economy can sustain before inflationary

pressures build. Added to this uncertainty is increasing evidence that the

relationship between economic slack and inflation is relatively weak as long as

inflation expectations remain firmly anchored.

23

As a result, inflation near

2 percent—by itself—is no longer a sufficient signal that the economy has

reached maximum sustainable employment.

The increased uncertainty about the level of maximum sustainable

employment poses a challenge to the conduct of monetary policy. When

deciding on monetary policy actions, the Bank looks ahead and adjusts the

degree of monetary stimulus to affect the level of total demand and help

close the output gap. Because inflation expectations are well anchored at

2 percent, inflation should return sustainably to target when slack is absorbed

and the economy is restored to maximum sustainable employment and its

productive capacity. However, with increased uncertainty regarding the level

of maximum sustainable employment, the risk of misjudging the appropriate

stance for monetary policy has increased.

Identifying the level of maximum sustainable employment has never been

easy. Indeed, many researchers have documented the wide confidence

intervals associated with estimates of the output gap or of the non-

23 Economic slack refers to resources in the economy that are not being fully utilized. These resources include

people who would like to work but are unable to find a job as well as machinery and equipment that are not being

used.

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 24

accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU)—a commonly used

measure of maximum sustainable employment. It should not be surprising

that identifying maximum sustainable employment is challenging because the

labour market itself is not one single market. It is, in fact, the sum of many

markets, differentiated by a variety of characteristics, including skill, industry

and location. Consequently, it is difficult to know whether everyone who

wants to be working is doing so, in a job that matches their skill set.

Ongoing structural changes in labour markets over the past few decades have

caused the level of maximum sustainable employment to change, making this

challenge even greater (Box 4). For example, an aging population and higher

levels of immigration have had an impact on the mix of workers’ skills. At the

same time, globalization and technological change—especially

digitalization—have affected labour demand. These still-evolving forces have

shifted the demand for and supply of different skill sets, and their net effect

on maximum sustainable employment is unclear.

Box 4:

Evolving uncertainties about the estimation of the

output gap and maximum sustainable employment

Economic research has documented the substantial uncertainties around the

measurement of unobservable variables, such as the output gap and maximum

sustainable employment.

24

These variables feature prominently in the

macroeconomic models that central banks use to predict when inflationary pressures

will emerge.

Structural changes in labour markets—driven by ongoing demographic shifts,

globalization and technological change, especially digitalization—have heightened

these uncertainties. These changes are affecting the demand for and supply of

different skill sets and possibly creating job mismatches. Since the 2008–09 global

financial crisis, employment rates (defined as the ratio of employed individuals to

24 Champagne, Poulin-Bellisle and Sekkel (2018) and Barnett, Kozicki and Petrinec (2009) show that the Bank of

Canada’s real-time estimates of the output gap are subject to large revisions. Similar results have been found for

other countries. For example, Orphanides and Van Norden (2002) show that real-time econometric estimates of

the output gap in the United States are subject to large revisions. Uncertainties around estimates of the non-

accelerating inflation rate of unemployment in Canada have been documented by Rose (1988) and Setterfield,

Gordon and Osberg (1992). Recent work by Brouillette et al. (2019) also finds that estimates of the trend

unemployment rate in Canada continue to come with large confidence intervals. These uncertainties around

estimates of maximum sustainable employment are also well established for other countries. For example, Staiger,

Stock and Watson (1997) report that it is not uncommon for the 95 percent confidence bands for the US NAIRU to

be roughly 3 percentage points.

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 25

working-age population) for both men and women have remained below their pre-

recession levels (see Chapter 2). These lower employment rates are partly due to

long-term declines in the labour force participation rates of individuals aged 15 to

24, which are the result of increased school enrolment. However, these changes have

been accompanied by a rising prevalence of part-time or short-term work, especially

among young Canadians.

25

A related but distinct trend is the increase in “gig”

employment in which the worker is an independent contractor rather than an

employee.

26

While the net effects of these forces on maximum sustainable employment are

unclear, uncertainty about the level of maximum employment appears to be

particularly high after recessions. All of the decline in jobs involving routine work in

Canada occurred during recessions (Blit 2020), reinforcing the notion that firms

restructure their production processes during these times.

27

The share of long-term

unemployed workers rose in Canada during the global financial crisis (Kroft et al.

2019). A longer duration of joblessness not only increases the tendency for

unemployed individuals to leave the labour force but also reduces the likelihood that

non-participants will enter the labour force to search for jobs.

28

This suggests that

the trends in labour force participation and job polarization are intertwined. Areas

more severely hit by the global financial crisis in the United States observed a

persistent decline in their employment rates as workers chose to leave the labour

force (Yagan 2019), suggesting the possibility of labour market hysteresis.

29

The question of how to respond to increased uncertainty about the level of

maximum sustainable employment is further complicated by growing

evidence that the slope of the Phillips curve—the relationship between

inflation and economic slack for a given level of expected future inflation—is

flatter than previously thought. This means that inflation is less sensitive to

25 Morissette (2021) finds that since 1976, among youth aged 15–30 who are not in school, the proportion working

part-time as opposed to full-time jobs has increased substantially, and most of this increase has been involuntary.

26 More information about the gig economy can be found in Kostyshyna and Luu (2019) and Jeon, Liu and

Ostrovsky (2019). Also, for research on multiple-jobholding patterns, see Kostyshyna and Lalé (2019).

27 A growing line of research classifies jobs as routine or non-routine based on descriptions of the tasks required.

Jaimovich and Siu (2020) suggest that the hollowing out of routine jobs in the United States is concentrated

during recessions.

28 The unemployment rate is an imperfect measure of total slack (excess capacity in the form of potential workers)

in the labour market. For example, during a downturn, previously active job seekers may get discouraged and stop

looking for work, and people intending to enter the labour force may put off doing so. At such times, participation

in the labour market falls, and this can give misleading signals about how much employment really exists.

29 For a recent examination of the similarities between the Canadian and US labour markets, see Albouy et al.

(2019).

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 26

changes in economic conditions. The evolving view of the relationship

between inflation and economic slack reflects not only the success of inflation

targeting in anchoring inflation expectations since the 1990s but also recent

research (Box 5).

30

Box 5:

Implications of a flat Phillips curve

The Phillips curve (PC) plays an important role in macroeconomic modelling in

academia and at central banks. Broadly speaking, the PC relates inflation to a

measure of economic slack, such as the output gap or the deviation of

the

unemployment rate from an estimate of its natural rate and expected future

inflation.

31

Although estimates of the PC can depend on model specification and sample period,

evidence is growing that the slope of the PC since the early 1990s has been relatively

flat (Landry and Sekkel, forthcoming).

32

A flatter slope of the PC means that large

fluctuations in the output gap are consistent with relatively stable inflation (Ball and

Mazumder 2011; Del Negro et al. 2020).

The flatness of the slope of the PC has important implications for how informative

inflation is about whether the economy is close to the maximum sustainable level of

employment (or potential output). In practice, inflation is measured imperfectly, and

transitory shocks (e.g., short-term supply disruptions) can temporarily affect the level

of inflation. With a flat PC and shocks to inflation, inflation can often be close to

2 percent even if the economy is below (or above) maximum sustainable

employment

or potential output.

33

30 See Kryvtsov and MacGee (2020) for a review of recent research on inflation dynamics and experience with

below-target inflation.

31 See Cacciatore, Matveev and Sekkel (forthcoming) for a more in-depth discussion.

32 The formulation of the PC has evolved together with macroeconomic thinking (see Gordon 2011). Beaudry and

Doyle (2000) estimate an accelerationist version of the PC for Canada and detect a decrease in the slope around

1990. Kichian (2001) estimates a time-varying parameter PC and finds similar evidence. Recent structural estimates

of the New Keynesian PC by Corrigan et al. (2021) also find a relatively flat PC for Canada. Recent innovative work

by Hazell et al. (2020) uses US regional data to identify the slope of the PC and concludes that the slope has been

flat since the 1980s. Furthermore, they argue that the sharp drop of inflation in the United States during the 1980s

was mostly due to shifting long-term inflation expectations. Similarly, Fitzgerald et al. (2020) use data from

metropolitan statistical areas in the United States from 1976 to 2010 and find a stable relationship between the

unemployment rate and inflation. Ongoing research explores the possibility of a convex PC—that is, the slope of

the PC increases the more the economy grows above potential. To date, the literature has not reached a clear

consensus on the convexity of the PC (Cacciatore, Matveev and Sekkel, forthcoming).

33 The estimated slope can depend on whether one uses a measure of core consumer price index (CPI) inflation or

total CPI. Although measures of core inflation are less volatile than total CPI and provide a better measure of

underlying inflationary pressures, they do not filter out all temporary shocks (see Box 1).

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 27

An example that illustrates how a flatter PC could lead to current inflation being less

informative about maximum sustainable employment is shown in Chart 5-A. Building

from a two-equation model where inflation and potential output are both subject to

unobservable shocks, Cacciatore, Matveev and Sekkel (forthcoming) infer the

probability distribution for the output gap, conditional on inflation being at

2 percent.

34

Shaded areas in the chart represent the probability of the level of the

output gap (with 95 percent confidence). The two curves correspond to pre- and

post-1990s estimates of the slope of the PC reported by Hazell et al. (2020). With a

flatter slope (seen in the smaller value of the slope coefficient, κ), the distribution of

the output gap becomes much more dispersed. As a result, with inflation at

2 percent, a flatter slope means that confidence that the output gap is closed is

much lower.

A relatively flat Phillips curve poses a two-sided risk to monetary policy. On

one hand, it suggests that a more patient approach to tightening monetary

policy could have modest impacts on inflation in the near term. On the other

hand, it implies that if monetary policy is slow to respond to a sustained

34 Carter and Mendes (forthcoming) offer an alternative approach that allows the PC to take a nonlinear, convex

shape under which the curve steepens as the output gap becomes more positive. In this context, inflation

outcomes are relatively uninformative about the maximum sustainable level of output at low levels of output but

become more informative at higher levels of output.

Chart 5

-A: A flatter Phillips curve means inflation is less informative about the

output gap

Note: The two distributions of the output gap are derived using alternative values of the slope of the Phillips curve,

κ, taken from

Hazell et al. (2020). The pre

-1990s value is 0.0107 and the post-1990s value is 0.005.

-15 -10 -5 0

Output gap (percent)

κ

0.0107

κ

0.005

5 10 15

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 28

buildup of inflationary pressures, bringing inflation back to its target may be

costly.

With a flatter Phillips curve, observing inflation near 2 percent is less likely to

imply that the economy is operating near maximum sustainable employment

(see Box 5). Given the uncertainty associated with ongoing structural changes

in labour markets, this suggests that it is now more difficult to know when

maximum sustainable employment is attained and the output gap is closed.

This raises the question of whether changes to the practice of monetary

policy could help the Bank better assess the maximum level of sustainable

employment consistent with the 2 percent target for inflation. For example, a

patient approach to applying monetary stimulus could help draw individuals

with limited attachment to the labour force into more productive employment

and help reduce persistent disparities in economic opportunity and income.

However, inflation expectations must remain well anchored for monetary

policy to succeed in keeping inflation on target.

Historically high levels of private debt

The historically high level of debt relative to gross domestic product (GDP)

among households and businesses remains an important consideration for

the conduct of monetary policy. Since 1990, household sector debt relative to

GDP has doubled and now exceeds 100 percent.

35

Although private, non-

financial business debt has grown more slowly since 1990, it also exceeds

100 percent of GDP.

36

With the expectation that interest rates will remain low

as a result of a low neutral rate of interest, the risk of a further buildup of debt

and associated financial vulnerabilities remains a concern (e.g., see the Bank’s

2021 Financial System Review).

Since the 2016 renewal of the monetary policy framework, the Bank has been

mindful of the risks associated with high levels of household or corporate

debt (Bank of Canada 2016). Elevated debt levels may create a difficult trade-

off between stabilizing inflation today and doing so tomorrow in the face of

35 Despite the doubling of household debt relative to GDP, the fraction of household income spent on debt

payments remains slightly below its 1990 level. While the rise in debt has led to higher principal payments, the fall

in nominal interest rates has lowered interest payments by more.

36 For a discussion of some of the challenges involved in measuring private, non-financial business debt, see

Duprey, Grieder and Hogg (2017).

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 29

financial vulnerabilities or macroeconomic imbalances (Beaudry 2020a).

37

Monetary policy can mitigate some concerns about elevated financial

vulnerabilities by flexibly adjusting both the horizon for returning inflation to

target and the corresponding interest rate path (Bank of Canada 2011; 2016).

One tool to help quantify these potential trade-offs is the Bank’s recently

developed growth-at-risk framework (Adrian, Boyarchenko and Giannone

2019; Duprey and Ueberfeldt 2020; Boire, Duprey and Ueberfeldt 2021). While

the growth-at-risk framework offers important insight, research continues on

how best to model the intertemporal trade-off generated by elevated debt

levels and incorporate it into monetary policy decision making.

38

Research is continuing into the mix of policies that could best mitigate and

limit the buildup of financial vulnerabilities.

39

Based on the recent Canadian

experience, a variety of prudential, macroprudential and housing policy

instruments exist that are better suited than monetary policy to address these

vulnerabilities (Box 6). Further investments in strengthening Canada’s

macroprudential policy framework could also potentially increase the

effectiveness of these policies (International Monetary Fund 2019). Given the

importance of financial stability for good macroeconomic performance, this

issue will remain important for monetary policy.

40

37 The Bank discussed the possibility that some alternative paths for the policy rate could have similar implications

for inflation but different implications for the level of financial vulnerabilities. This illustrates that in some

situations no trade-off may exist between stabilizing inflation today and stabilizing it tomorrow in the face of

financial vulnerabilities. Monetary policy can also be a blunt and costly tool to target financial vulnerabilities,

especially compared with other tools such as macroprudential policies (Bank of Canada 2016).

38 The growth-at-risk concept provides a quantitative assessment of the trade-offs between different risks. In this

framework, choosing a rate path to minimize the departure of inflation from the target not only minimizes

macroeconomic risks to economic growth but also has consequences for financial stability risks to economic

growth. The framework still involves an element of judgment, as many of the relationships are estimated

imprecisely. Current research focuses on developing a framework that is more explicit about the mechanisms at

play—for example, exploring the formation of expectations, which can play a key role in the development of

financial vulnerabilities because departures from rational expectations can amplify boom-bust dynamics.

39 For a recent example, see Schroth (2021).

40 A related consideration is that high levels of debt may affect the transmission of monetary policy (e.g., Kaplan,

Moll and Violante 2018; Cloyne, Ferreira and Surico 2020). For example, Kartashova and Zhou (2020) examine how

Canadians with mortgages, which account for the majority of household debt, respond to changes in interest rates

when their mortgages come up for renewal. The authors find that changes in interest rates at renewal have an

asymmetric impact on consumer durable spending, deleveraging and defaults, with borrowers deleveraging if

rates rise at renewal. These asymmetric responses point to a risk that consumption could become more sensitive

to changes in interest rates.

Monetary Policy Framework Renewal | 2021 | Page 30

Box 6:

Macroprudential and monetary policy—Canadian

experience since the global financial crisis

For over a decade, the Bank of Canada has emphasized the evolution of household

financial vulnerabilities in its Financial System Review. Macroprudential policies have

adapted to address the vulnerabilities in Canadian housing and mortgage markets. In

particular, federal authorities—both the Department of Finance Canada and the

Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI)—implemented and

expanded stress tests for insured and uninsured mortgages. These built on earlier

measures introduced between 2008 and 2012 to lower the riskiness of new mortgage

debt.

Following the global financial crisis, federal mortgage insurance qualification criteria

were tightened. Between 2008 and 2012, the maximum amortization of insured

mortgages was lowered from 40 to 25 years, and the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio limit

was reduced from 100 to 95 percent for a purchase and from 95 to 80 percent for

refinancing.

41

Overall, the rule tightening likely contributed to slower credit growth

after 2012 despite continued low interest rates (Chart 6-A).

The Bank’s policy rate remained constant between September 2010 and January

2015. In 2015, a sharp decline in oil prices prompted the Bank to cut its policy rate to

50 basis points. This reduction, along with continued downward pressure on long-