The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 56

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-

Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Jason Drysdale

University of Colorado Denver

Abstract

Collaborating with faculty is an integral part of the instructional designer’s role. However, faculty

can be skeptical regarding the added value of the instructional designer’s expertise and

contribution in helping them (Intentional Futures, 2016). Additionally, instructional designers

experience a high degree of job misperception and struggle to advocate for clear and defined roles

(Drysdale, 2018). Four primary responsibilities of instructional designers in higher education were

defined by evaluating the industry standard models of instructional design, comparing their

structure and usage for relevance to the consultative role designers assume in higher education.

The collaborative designer piece was missing from the literature leading to the development of the

collaborative mapping model (CMM) that puts relationship at the center of higher education

instructional design and addresses issues of scale, quality, and empowerment. Development of the

CMM was informed by several key theories and concepts, including authentic leadership theory

(Kiersch & Byrne, 2015), shared leadership theory (Bolden, 2011), and appreciative inquiry (Kadi-

Hanifi et al., 2014).

After several years of implementation and refinement, the preliminary research described here was

conducted to examine the effectiveness of the model toward facilitating the collaborative

relationship between instructional designer and faculty. Fifty faculty who had designed a course

in partnership with an instructional designer through the CMM were surveyed regarding their

experience with the process. Among the results, 92% of the 37 respondents indicated an

improvement in the quality of their courses and 73% indicated that they saved time by working

with an instructional designer in the CMM. Key themes included an increased value and respect

for the expertise of the instructional designer, a significant improvement to the quality of online

courses designed and developed through the CMM, and enthusiasm for continued collaboration

with instructional designers. This study describes the development of the model, an overview of

theoretical influences and processes, and the results of research examining the effectiveness of the

CMM of instructional design.

Keywords: instructional design, instructional design models, collaboration, faculty

partnership, advocacy, leadership, course mapping, curriculum design, professional roles

Drysdale, J. (2019). The collaborative mapping model: Relationship-centered instructional

design for higher education. Online Learning, 23(3), 56-71. doi:10.24059/olj.v23i3.2058

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 57

The Collaborative Mapping Model:

Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

While higher education administrators may recognize the value instructional designers

bring to online learning, limited resources for staffing can inhibit the kind of growth needed for

institutional leaders to effectively empower them (Fredericksen, 2017). Brigance (2012) suggested

that instructional designers are positioned to be leaders in their institutions, due to their significant

expertise in online learning and instructional design. French and Raven (2010) posited that this

expert power has the potential to increase social influence. Instructional designers, as leaders with

influence but not overt authority, can advocate for their role as partners with faculty. However,

designers often struggle to persuade resistant faculty to collaborate and often find it challenging to

stay focused on their primary work: the conceptual design of courses through consultation with

faculty (Intentional Futures, 2016). This key role is frequently misperceived or misrepresented,

stretching instructional designers thin and allowing secondary job responsibilities to overtake the

primary work of design collaborations (Drysdale, 2018). According to Seaman, Allen, and Seaman

(2018), recent enrollments in online courses have been increasing while face-to-face enrollments

have decreased. Expertise in online learning design is more vital than ever in order to recruit,

retain, and graduate students through high-quality online programs (Shaw, 2012). A new model of

instructional design focused on collaboration and building positive relationships between faculty

and designers was developed to address these challenges of misperception, collaboration,

scalability, and quality. Known as the collaborative mapping model (CMM), this approach to

instructional design encourages faculty and designers to value each other’s considerable and

distinct expertise. The CMM was developed specifically to address the unique challenges

instructional designers face in higher education. After several CMM design model iterations from

2014 and 2017, this paper presents the findings of research to assess the effectiveness of the model

from the perspective of faculty who designed online courses in partnership with an instructional

designer using the CMM process. Developed specifically for higher education, the CMM is

positioned differently than other models of instructional design, the most ubiquitous of which are

rooted in the fields of corporate training and professional learning.

Literature Review

Instructional design is a field of practice that focuses on the design, development, and

implementation of learning experiences (Saba, 2011). The design of learning is enacted and guided

through models of instructional design. Andrews and Goodson (1980) conducted a pivotal study

comparing a range of instructional design models that were developed by individual practitioners.

They discovered that most models of instructional design emerged from the individual

experiences, context, and perspective of their creators, and that many were modifications of

previously existing models of design (Andrews & Goodson, 1980). Sixty-five percent of the

models compared in the study claimed a theoretical origin, including learning theory, while 50%

claimed an empirical origin; these underpinnings were not mutually exclusive (Andrews &

Goodson, 1980). Models of design from this study espoused one of three purposes: teaching the

instructional design process, production of instructional products and materials, or a reduction in

the cost of education (Andrews & Goodson, 1980, p. 11). Further, each model had a focus on either

the design of single learning experiences or systems of learning, such as programs or curricula

(Andrews & Goodson, 1980).

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 58

Gustafson and Branch (2002) produced a taxonomy of instructional development models,

which they defined as inclusive of both design and development practices. They categorized the

included models of development into three classifications: classroom-centric, or created to

improve small-scale instruction; systems-centric, or created to design and improve programs and

curricula; and product-centric, or created to facilitate development of instructional materials

(Gustafson & Branch, 2002). The taxonomy described characteristics of design models in relation

to these three orientations, including team or individual effort, the skill needed to successfully

implement the model, and the anticipated degree of iteration (Gustafson & Branch, 2002, p. 34).

The models included in the taxonomy were developed for situational use and lacked a clear,

pervasive approach aside from a commitment to the basic tenets of instructional systems design:

analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation (Gustafson & Branch, 2002).

Neither Gustafson and Branch’s (2002) taxonomy nor Andrews and Goodson’s (1980) comparison

of design models were organized by modality. However, since the advent of the Internet as a native

and ubiquitous environment for learning, this characteristic has become an important facet of

instructional design models, particularly those used in online learning.

Although many instructional design models exist, three have emerged in the field as the

primary processes used across different industries, iterated upon both formally and informally

based on context: ADDIE, AGILE, and backward design. However, these instructional design

models operate less as clear processes for designing and developing learning systems and

experiences than as design philosophies or approaches that inform the work, role, and focus of

instructional designers.

The ADDIE Model

The ADDIE model—which stands for analyze, design, develop, implement, and evaluate—

is of uncertain origin; some suggest that it emerged at Florida State University from work

commissioned by the U.S. Army, although the acronym ADDIE was not formally used during the

project (Molenda, 2003). Further, ADDIE did not appear in any of the major literature around

instructional design models from the 1980s or 1990s (Molenda, 2003). As a result, Molenda (2003)

concluded that ADDIE was “merely a colloquial term used to describe a systematic approach to

instructional development, virtually synonymous with instructional systems development” (p. 35).

Still, the key tenets of ADDIE have become the cornerstone of instructional design and

development processes across many contexts; ADDIE is widely characterized as the traditional

industry-standard model of instructional design.

In each phase of ADDIE, the instructional designer works with a subject matter expert

(SME); the focus of ADDIE is on the systematic and intentional creation of high-quality learning

materials. The ADDIE approach begins with assessing the needs, environment, and characteristics

of learners through detailed analysis. The next stage, design, moves from needs assessment to

conceptualizing interventions and experiences tailored to learners, and informed by the SME. The

development phase is inclusive of all steps for product development, and often emerges as a back-

and-forth between the instructional designer, who produces storyboards, writes copy, creates

assignments, and develops rubrics or assessment metrics, and the SME, who provides content and

feedback. In the implementation stage, students learn using the developed materials; the ADDIE

model culminates in an evaluation of their learning and the effectiveness of the instructional

materials created through the design process. As an instructional design model, ADDIE takes a

broad approach to categorizing the activities of instructional design with significant leeway given

for the perspectives and process of each instructional designer or team. The model emphasizes the

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 59

development of quality products—the materials created as a result of the instructional design

process.

The AGILE Model

The AGILE model—which stands for align, get set, iterate and implement, leverage, and

evaluate—was developed by Conrad Gottfredson, and has roots in agile software development and

project management (Neibert, 2013-a). The agile philosophy emphasizes prioritization and

iteration for the purpose of rapid development and deployment of learning solutions that meet the

performance needs of an organization. Often used in the design and development of e-learning

materials—technology-driven learning experiences often delivered in a self-paced, asynchronous

format—the AGILE model has become a standard practice in corporate and professional e-

learning environments where the emphasis is on an accelerated pace of delivery and a team-centric

approach to learning development. In AGILE design, the first stage of work is alignment: ensuring

that stakeholders and team members are aligned on strategy and business needs for the project, as

well as the value it will add for learners (Neibert, 2013-a).

The second stage of AGILE, get set, focuses on analysis of the audience, performance

goals, the operational demands of the project, and, in complex projects, establishing a learning

experience and performance plan (LEaP) as a support mechanism for learners (Neibert, 2013-b).

This is the primary planning stage prior to the development of instructional materials in Stage 3,

known as iterate and implement. This phase focuses on rapid cycles of development and

incremental implementation, with a stated purpose of creating adaptable learning experiences at a

scale and pace that meet the needs of the organization (Neibert, 2014). The final two stages,

leverage and evaluate, focus on access and quality: leveraging the technology resources of an

organization for pervasive delivery and evaluating the quality and success of the learning

experiences developed (Neibert, 2014). Although AGILE has similarities to ADDIE, it repositions

the role of the instructional designer to one participant of a larger team working to produce learning

materials for specific business needs. AGILE methodology encourages rapid iteration and detailed

project management as vital responsibilities for all stakeholders. As a result, the focus of the

AGILE model is on improving the efficiency of processes, leading to responsive product

development that results in a change seen as valuable to the organization and, ideally, the learner.

Backward Design

Backward design was first defined by Wiggins and McTighe (2005) as a method of

planning learning by focusing first on the intended outcomes for students, then moving backward

through their stages of engagement: outcomes, assessments, and learning activities. This approach

to curricular and classroom planning, also known as Understanding By Design (UbD), encourages

a student-centric approach to learning design that shifts the focus of learning design and teaching

from content to student learning (Bowen, 2017). The stages of backward design are informed by

the experience and perspective of the faculty or instructional designer. Many focus on outcomes

development through the use of Bloom’s taxonomy, which places action verbs into categories of

student engagement based on the level of sophistication and challenge (Bloom, 1956). Others

center on outcomes development as an exercise of identifying academic, content-specific, or

professional skills in which students will be expected to be proficient upon completion of the

course. The next element of backward design is to describe the assessments which measure student

growth on the intended outcomes. The final stage is to define learning experiences, curate

resources, and develop learning materials that prepare students for the identified assessments

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 60

(Bowen, 2017). Backward design has been operationalized into a method of instructional design

or curriculum planning; however, Wiggins and McTighe (2005) did not intend for their approach

to be seen as a prescriptive method of design but as a means of focusing design work on the needs

of students. Similar to both ADDIE and AGILE, backward design is an approach to learning design

intended to frame the work of instructional design but not to strictly dictate its method or process.

Still, backward design has been adopted as a formal process of instructional design and is largely

focused on producing high-quality, student-centered learning experiences.

The Missing Piece: Defining the Roles of Instructional Designers in Higher Education

ADDIE, AGILE, and backward design were not intended as formalized processes or

models of instructional design but as approaches to design, upon which instructional designers and

teams iterate based on the unique needs and expectations of their contexts and learners. However,

all three have been operationalized as formal approaches to instructional design, each with a key

focus on either process or product development. As none of these models were developed

specifically for the needs of faculty or instructional designers in higher education, each has been

adapted to the meet the needs of the higher education context. As a part of this research into the

commonly used instructional design models, the roles instructional designers play at institutions

of higher education became a further focus of interest. Gustafson and Branch (2002) characterized

the design and development of learning as two separate but connected processes. Intentional

Futures (2016) identified four common tasks associated with instructional designers: designing

courses, training faculty, technology support, and project management. These core responsibilities

of instructional designers were further categorized into four key roles: traditional designer, course

developer, technology support, and collaborative designer. These roles each have a different area

of focus, associated with the design models that align most with their primary set of

responsibilities. Additionally, the roles were categorized by the type of leadership exhibited and

experienced by designers who assume these roles: collaboration focused or compliance focused,

and high oversight or high autonomy. These leadership categories were influenced by Blake and

Mouton’s (2010) managerial grid, which described management style in relation to the degree of

concern for production or people. Roles with high compliance or high oversight were categorized

as focused more on process or product than people, while the role with high collaboration and

autonomy—collaborative designer—was categorized as focused more on relationship. Figure 1

shows the results of this categorization, with instructional designer roles associated with a specific

model of instructional design.

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 61

Figure 1. Roles and associated models of instructional design.

This categorization of instructional designer roles and models became the basis of

development for the CMM: No ubiquitous model of instructional design had been developed and

implemented for the collaborative designer role, which focused on relationship rather than on

product or process.

Traditional designer. Professionals with a traditional instructional designer role focus on

designing high-quality products, such as online courses or modules, in concert with a faculty

member who acts as the SME for the project. Traditional designers operate as their own project

managers, coordinating all aspects of the design or redesign project, including setting up meetings

and establishing deadlines for deliverables from SMEs. Primary decision-making authority over

the instructional decisions of the course—such as pedagogy, assignment types and differentiation,

structure of the learning experiences, and assessments—are made by the instructional designer.

SMEs, however, maintain expertise and authority over content—course readings, articles, videos,

case studies, and any other passively consumed information relevant to and valuable for students

in the course or learning experience. The designer–faculty relationship, in this context, focuses on

mediating differences of opinion and value, working toward consensus from two different

perspectives on the purpose and value of the course. While both designer and faculty member have

equal authority, their expertise covers different areas, and they often operate independently, with

meetings focused on cycles of iteration, mediation, and approval in order to deliver a high-quality

design and—if timelines allow—a developed product. The traditional designer role is most closely

associated with the ADDIE model of instructional design.

Course developer. Instructional designers with a course developer role operate primarily

as developers of instructional materials, including digital media, documents, presentations, and

content or assignments which integrate use of instructional technology tools. Course developers

often work directly within a learning management system or with e-learning authoring software to

produce course copy and content for faculty, focusing on cycles of design iteration for these

materials based on faculty feedback. The designer–faculty relationship for course developers

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 62

favors the authority of faculty, as they are expected to possess both the content knowledge and

teaching expertise, while the instructional designer focuses their skills on technology training and

development of learning resources. The course developer role is most closely associated with the

AGILE model of instructional design.

Technology support. Instructional designers with a primary focus on technology support

experience both course design and development as a peripheral responsibility. Their focus is first

on providing customer service and training to faculty in the use of instructional technologies. Tasks

or responsibilities for designers in a technology support role may include phone, chat, or direct

support, ticket escalation, formal and informal consultation on instructional technology, and

troubleshooting issues with technology. Although critical for faculty and student success, this role

occupies a peripheral place in instructional design and development. As such, no model of

instructional design was associated with technology support.

Collaborative designer. Instructional designers with a collaborative design role focus

foremost on the pedagogical work of learning design. They view faculty as partners and

collaborators in the process of conceptualizing learning and adopt a student-centered mindset.

Collaborative designers hold no direct decision-making authority over courses but instead rely on

their influence and expertise to guide faculty toward innovative designs inclusive of the unique

perspectives, values, and expertise of their faculty partners. Collaborative designers do not see

faculty as SMEs, but as co-teachers with different expertise and shared investment in the well-

being and transformative learning of their students. Production of learning materials may or may

not be an expected responsibility of collaborative designers; regardless, their focus is first on

pedagogy, and all decisions on technology or developing instructional materials are filtered

through the lens of pedagogy. Although the backward design approach is often used by

collaborative designers, it is not a model intended for or focused on the collaborative relationship

between instructional designers and faculty.

Through this process of discovery, it became apparent that no widely known model of

instructional design had been specifically created or implemented for the collaborative designer

role, specifically the relationship between higher education faculty and instructional designers. I

developed the CMM to address the clear gap in design models associated with the role of the

collaborative designer in higher education. Each of the other roles of instructional design focus on

either product or process, while collaborative designers focus first on relationships. Collaborative

designers foster shared investment, collaborate from different frames of expertise, and value

faculty members as far more than SMEs: These designers see SMEs as the teachers, content

experts, mentors, and practitioners that must have their visible presence and active influence

infused into the courses they teach to help students improve their lives and learning.

Conceptual Influences on the Collaborative Mapping Model

The CMM has four primary conceptual influences: authentic leadership theory, shared

leadership theory, appreciative inquiry, and backward design. Kiersch and Byrne (2015) define

authentic leaders as those who “are transparent and consistent in decision making and in

interactions with followers. They situate themselves to make well-informed decisions by

encouraging followers to voice diverse viewpoints and by incorporating those decisions into their

decision-making process” (p. 293). Authentic leaders act based on their values and morals; they

espouse integrity and expect their colleagues and followers to act in kind (Kiersch & Byrne, 2015).

In the collaborative designer role, instructional designers act as leaders; the CMM encourages

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 63

designers to act with authenticity, emphasizing diverse perspectives and a values-centric approach

as critical elements of successful partnership and design. As collaborative designers do not hold

authority over faculty but possess influence based on their expert power (French & Raven, 2010),

authentic leadership is the cornerstone of positive relationship development.

Bolden (2011) described leadership as “not the monopoly or responsibility of just one

person” in shared leadership theory but as the collective responsibility and social process found in

teams and professional relationships (p. 252). Shared leadership de-emphasizes the single

authoritative leader, instead focusing on leadership as a process distributed to two or more people.

In the collaborative designer–faculty relationship, both people hold significant but different frames

of expertise and responsibility. Shared leadership theory and the CMM encourage a collaborative

approach to decision-making and inquiry, rather than paradigm based on authority and independent

responsibility.

Appreciative inquiry (AI) is an approach to change management that focuses on positive

core questioning as a means of enacting change, rather than the identification of problems or

challenges. The core value of AI is in its focus on positive inquiry: “its ability to engage, enthuse,

energize and enhance learning communities” (Kadi-Hanifi et al., 2014, p. 584). The four stages of

AI, known as the 4D cycle, are discovery, dream, design, and destiny (Kadi-Hanifi et al., 2014).

The discovery phase facilitates an exploration of the things people value most in their current

environments and relationships. The dream phase encourages thinking beyond the scope of the

current environment, instead imagining and casting a vision for the best future built on the

foundation of the elements shared in the discovery phase. The design phase focuses on

conceptualizing a plan to realize the future and vision from the dream phase; destiny, the final

phase, outlines a commitment to change, fueled by the shared investment created in the previous

phases of the 4D cycle (Kadi-Hanifi et al., 2014). Appreciative inquiry influenced the CMM as the

means for building shared investment between instructional designers and faculty; rather than

focus on perceived problems in a course or with the people designing the course, appreciative

inquiry promotes the things that matter most and elevates those in the design of learning

experiences.

Although backward design is an influence on the CMM, it does not strictly guide the

process of design used in the model. Rather, the CMM retains a focus on students rather than on

content or assessment as the starting point for design. This focus may be realized in a variety of

ways based on the perspectives and preferences of both the instructional designer and the faculty

member. Examples include developing formal learning outcomes or a commitment to the

emergence of learning based on the input and contributions of students.

Process Overview of the CMM

Like other models of instructional design, the CMM consists of two overarching elements:

the design of learning experiences and the development of instructional materials. In the CMM,

these elements are structured as two distinct phases; the roles of both instructional designer and

faculty change in each phase. In the design phase, the instructional designer guides the faculty

member through a process of inquiry regarding their students and the course, visualizing the

conversation into a course map that captures the different elements present in the learning design:

overall course structure, topics, passive learning resources, learning activities and assignments,

outcomes, and alignments.

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 64

Design phase. The design phase consists of a series of five mapping meetings—sometimes

more, sometimes less, depending on the complexity of the design and the emerging faculty–

designer partnership—each with a different focus.

Consultation 1. The first meeting is a planning session for the designer to learn more about

the faculty member, their perspectives on and hopes for their students, their pedagogical

perspective, their experience with the modality in which they will be teaching, and the key

elements of their course. The instructional designer encourages faculty to not rely on previous

materials for this stage of inquiry; rather, the designer hears and learns about the faculty, the

course, and the students through conversation, in order to discover and reinforce the values and

perspectives that need to be infused into the course design or redesign. In this meeting, the

instructional designer also gives a process overview.

Consultations 2 and 3. The next two meetings focus on student outcomes. Although this

process varies from one designer to the next, the goal is to encourage faculty to think about their

perspectives on and hopes for students, and to write them as statements that will resonate with

students and frame their experience in the course. Outcomes development can be highly formalized

or less rigid; it can focus on Bloom’s taxonomy as a means of development or on framing the

course through participation, encouraging students to write their own outcomes in categories

related to the content of the course. There is room here for adaptability and flexibility based on the

perspectives and pedagogy of both the instructional designer and their faculty collaborator.

Consultations 4 and 5. The final two meetings are used for delineating topics within the

determined structure of the course, typically a weekly structure, and to conceptualize assignments

and align them to outcome statements. A critical element of these mapping sessions is faculty self-

discovery. Instructional designers do not aim to tell faculty what or how to change in the CMM,

which positions designers as evaluators or critics of faculty work. Rather, they facilitate self-

discovery through positive core questions and through shared ideation. Recommendations for

change then shift from criticisms of previous work to designing new ideas, pathways, solutions,

and ideas through partnership.

The instructional designer’s role during the design phase of the CMM centers around

positive core questions; examples of such questions include the following:

•

What are the things you love most about your course?

•

How would you envision this decision affecting your students’ learning?

•

How can I ensure that our time together is fruitful and helpful?

•

How do you envision your students changing as a result of the time they spend with

you and each other in this course?

•

What would you say makes your teaching and your course truly unique?

•

How does the structure of your course help your students build confidence as the

concepts increase in difficulty and complexity?

Such questions promote a sense of purpose in the meetings but also orient the time toward

positive relationship building. By asking questions about the faculty member, their course, and

their unique experience and perspective, the instructional designer demonstrates that they value

the faculty member and want to work in a collaborative capacity. For instructional designers, who

struggle to collaborate effectively with faculty (Intentional Futures, 2016), these questions also

help reinforce their role as expert pedagogical collaborators.

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 65

The mapping process of the design phase can be facilitated through any visual mapping

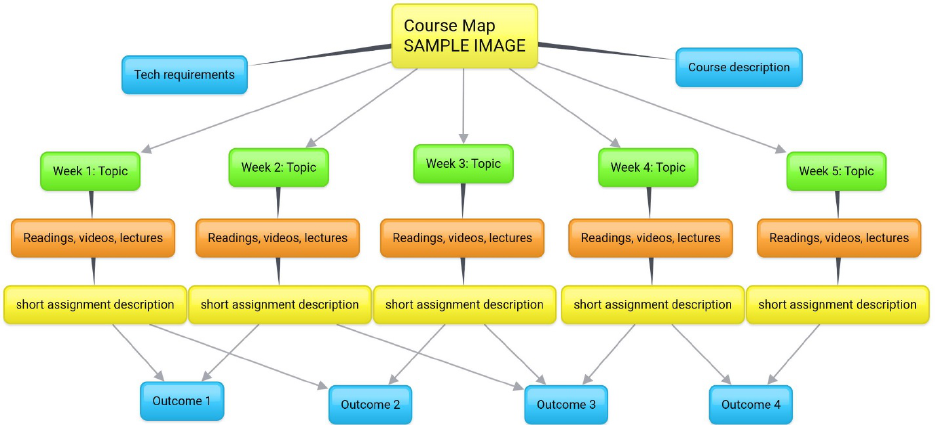

tool. A sample course map can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Course map sample image.

The course map template consists of a row on top for weekly topics, a middle row for

learning resources and materials, and a row for assignments and activities with an evaluated

deliverable. The outcomes row is situated on the bottom of the map, even though instructional

designers start with outcomes design. This is to visualize the course from the perspective and

experience of students, who first see and experience topics, then content, then assignments, which

ideally lead to outcomes. This structured map is not the only way to implement the CMM;

however, it is a useful way to visualize—for faculty and students alike—the experiences designed

into the course. The visual medium makes it easier to consider more opportunities for change in

both new and redesigned courses.

The first of these opportunities is workload balance and calculation, or how much time

students are asked to spend each week in the course, and what kind of engagement they will have

during that time. Another is the intentional design of the course as a system of learning: What is

the pedagogical approach taken throughout the course? Is it reinforced each week, or are there

spaces of divergence from the intended pedagogical perspective? Are learning activities diverse

enough to keep students engaged but consistent enough to build confidence and healthy rhythms?

Have your design decisions led to technology integration, or is technology driving your decisions?

Another opportunity is to adjust assignments or outcomes based on the visible alignment between

these two elements. It is simple to see outcomes or assignments that are not aligned, which become

opportunities for positive change in the course.

Development phase. In the development phase of the CMM, the instructional designer

transitions to a consultative role; rather than leading the mapping sessions, the designer now moves

into a role focused on providing feedback and guidance at the behest of their faculty partner, who

assumes primary responsibility for developing instructional materials. During the development

phase, faculty will ideally participate in a professional development course designed to give them

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 66

the experience of being an online student while also equipping them with teaching and

development skills to create their courses. In the absence of such a course, the instructional

designer may be consulted more frequently, and must manage expectations and maintain role

clarity with their faculty partners. Consultation topics include sharing assignment directions for

feedback, requests to review videos, or looking through the entire course to see if it is consistent

with the design created in collaboration. The faculty partner leads the development phase, while

the instructional designer coaches, consults, and provides feedback. This is a critical element of

the CMM, as it empowers instructional designers to focus their time primarily on design

collaborations, empowers faculty to create course materials through their unique experience and

presence, and makes the model scalable within the funding and personnel constraints common to

instructional design teams.

After several years of refining the CMM, I wanted to know if it was solving the challenges

that led to its creation. As a result, this study examined the effectiveness of the model from the

perspective of faculty who had designed a course in collaboration with an instructional designer

through the CMM. The research question was, “How has the CMM influenced the experience of

faculty designing and developing learning experiences in partnership with an instructional

designer?”

Method

To address this research question, I chose an action research design focused on evaluating

program effectiveness. Action research is an emergent process focused on solving practical

challenges through the discovery and implementation of creative solutions (Ivankova, 2015).

Further, action research “addresses specific practical issues that have value for a specific

community and professional setting” (Ivankova, 2015, p. 30). The CMM was developed to address

the practical challenges instructional designers have collaborating with faculty, addressing role

misperceptions, and advocating for their professional roles. As such, an action research design

focused on program effectiveness was the best way to assess the effectiveness of the model from

the perspective of faculty who had participated in instructional design using the CMM. The

population for the study was a group of 50 faculty who had designed an academic, credit-bearing

course in partnership with an instructional designer through the CMM, identified through

purposive sampling.

A survey consisting of eight closed-ended, Likert-style questions, and a single open-ended

question captured faculty reactions. The Likert-style questions were required, and the open-ended

question was optional. The survey was field tested by a group of SMEs, including instructional

designers familiar with the CMM, faculty, and researchers versed in qualitative, quantitative, and

action research methodologies. This focus group of experts provided feedback that helped clarify

the questions and ensure the validity of the survey. The survey was conducted through Google

Forms and was open for a period of 2 weeks; all submissions were anonymous, and any identifying

information from the open-ended question was de-identified and anonymized prior to data

analysis. The survey was sent out to identified faculty via email; I sent out reminders twice a week

during the data collection window to encourage a high response rate. Data were analyzed for the

Likert-style questions by calculating the mean for each response to each question. The open-ended

question was analyzed through an emergent qualitative coding pass in which I highlighted key

quotes and consistent themes from the participants’ responses.

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 67

Results

Out of the 50 participants, 37 responded to the survey for a response rate of 74%.

Respondents identified their perspective on Likert-style questions as strongly agree, agree,

neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree. The results of each Likert-style question may be found in

Table 1.

Table 1

Results of the Faculty Survey (N = 37)

Question

Strongly

Agree

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly

Disagree

The quality of my course improved

from working with an instructional

designer.

59.4%

32.4%

2.7%

0

5.4%

I plan to collaborate with an

instructional designer on a course

map again in the future.

78.3%

13.5%

2.7%

0

5.4%

Creating a course map made me

more open to developing the course

(writing assignments, etc.) with an

instructional designer.

43.2%

48.6%

2.7%

0

5.4%

Collaborating with an instructional

designer on a course map saved me

time designing my course.

54.0%

18.9%

18.9%

2.7%

5.4%

The collaborative mapping model

was useful for evaluating the design

and structure of my course.

54.0%

35.0%

5.4%

0

5.4%

Collaborating on a course map

made teaching my course more

seamless.

35%.0

40.5%

18.9%

0

5.4%

The collaborative mapping model

improved the quality of my course

design work as a faculty member.

48.6%

43.2%

2.7%

0

5.4%

The course map helped me evaluate

my course in ways I had not

previously considered.

62.1%

27%

5.4%

0

5.4%

The results of the Likert-style questions indicated a clear value associated both with

collaboration with an instructional designer and with the CMM, specifically with the development

of a course map. Eighty-nine percent of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that the course

maps helped them evaluate their courses in new ways. Seventy-five percent of respondents agreed

or strongly agreed that collaborating on a course map made their teaching more seamless, and 73%

agreed or strongly agreed that collaborating on a course map saved them time. Ninety-two percent

of respondents indicated that they intended to collaborate with an instructional designer again on

a course in the future.

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 68

The open-ended question at the end of the survey was, “How has collaborating with an

instructional designer in this model of course design helped you most as a faculty member?” Of

the 37 respondents to the survey, 18 chose to answer the open-ended question. One respondent

indicated that “the expertise of the instructional designer and his collaborative work style led to

productive work sessions, brainstorming, outcome development, and overall better design than I

could accomplish myself.” Another participant shared that “through mapping I learned that my

courses required too much work. I was able to eliminate some assignments which I think made the

remaining ones more meaningful.” One faculty member shared that it helped them “find

redundancy of material, gaps in content and improve assignments for stronger connections to the

content being taught.” Finally, two respondents shared that the collaboration with a designer was

new, though they were experienced teaching online. These participants indicated that “the

experience was absolutely wonderful and resulted in a polished product at the beginning of the

course,” and that after teaching online for 10 years, “with the instructional design group I feel I

am offering the best online course I have ever done.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the CMM of instructional

design from the perspective of faculty who had designed a course in partnership with an

instructional designer using the model. I administered a survey comprised of eight Likert-style,

closed-ended questions and one open-ended question to 50 faculty, chosen through purposive

sampling. The results indicated that faculty found significant value in collaboration with

instructional designers using the CMM. The results from the Likert-style questions indicated a

strong perception among respondents that the CMM—and collaborating with an instructional

designer—was beneficial and resulted in positive changes to their courses. Further, faculty

indicated an improvement to their teaching preparation, time investment, and openness to

collaboration with an instructional designer. Responses of disagree or strongly disagree were

minimal across all questions, and neutral responses were only of note in two questions, the first of

which asked if collaborating with a designer saved time, and the second of which asked if course

maps made teaching more seamless. The results from the Likert-style questions indicated strong

support for both the CMM and for faculty collaborating with an instructional designer.

Analysis of the open-ended question responses indicated three key themes: value and

respect for the expertise of the instructional designer, a significant improvement to the online

courses designed and developed through the CMM, and enthusiasm for continued collaboration

with instructional designers. Faculty participants noted that the designs they created were both

better than what they could have done independently and that they were the best online courses

they had ever offered. Further, two participants suggested that they wished the instructional

designers had more time available to work with them; this is both a reflection on the insufficient

size of the instructional design team from this study and the value the faculty members placed on

their expertise and input. None of the open-ended question responses indicated a misperception in

the role of instructional designers. No respondents referenced technology support, assistance, or

content development as the role of an instructional designer. Instead, responses focused on the

process of design, the collaboration with an instructional designer, the benefits experienced from

working with a designer, or the intent to continue working with an instructional designer.

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 69

Recommendations and Conclusions

Based on the data collected and analyzed in this action research study, the CMM appears

to be an effective model of design for instructional designers in higher education. Faculty indicated

that significant value was added to their work from partnering with an instructional designer in

this model, and they indicated no role misperceptions in their open-ended question responses.

However, there are limitations to the study, including the exclusive focus on faculty perceptions

of the value of the CMM. Instructional designers were not included in this study as participants;

further, the study was enacted through an action research model, a contextualized approach to

research intended to solve practical problems of practice. Although the CMM was designed to

solve profession-wide challenges in higher education instructional design, the data reflects the

results of only a single location and faculty body. While this is helpful and reflects a positive trend,

broader studies in a variety of higher education contexts—inclusive of the perspectives of

instructional designers—may be warranted. Additionally, an opportunity exists to evaluate the

effectiveness of the CMM for designing larger systems of learning than courses—specifically, full

academic programs.

I recommend that instructional designers and online learning administrators implement the

CMM at their institutions if they experience role misperception, challenges in collaborating

effectively with faculty, or have concerns about the scalability of quality instructional design for

online courses and programs. The data in this research study indicated a clear positive influence

on each of these issues. Focusing first on relationships, rather than product or process, builds a

truly collaborative culture between faculty partners and instructional designers.

Instructional designers hold unique and significant expertise that faculty often do not have;

they are positioned to be leaders of positive change at institutions of higher education but need the

tools and advocacy to have a visible and lasting influence. The collaborative mapping model

equips instructional designers toward this end: building meaningful relationships through

partnership in design, advancing the work of faculty and designers both for the betterment of

student learning.

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 70

References

Andrews, D. H., & Goodson, L. A. (1980). A comparative analysis of models of instructional

design. Journal of Instructional Development, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02904348

Blake, R., & Mouton, J. (2010). The managerial grid. In J. McMahon (Ed.), Leadership classics,

(pp. 185–199). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives handbook: Cognitive domains. New

York: David McKay.

Bolden, R. (2011). Distributed leadership in organizations: A review of theory and research.

International Journal of Management Reviews, 13, 251–269. doi:10.1111/j.1468-

2370.2011.00306.x

Bowen, R. S. (2017). Understanding by design. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/understanding-by-design/

Brigance, S. (2011). Leadership in online learning in higher education: Why instructional

designers for online learning should lead the way. Performance Improvement, 50(10),

43–48.

Drysdale, J. (2018). The organizational structures of instructional design teams in higher

education: A multiple case study (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from

https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd/115/

Fredericksen, E. E. (2017). A national study of online learning leaders in US higher education.

Online Learning, 21(2). doi:10.24059/olj.v21i2.1164

French, J., & Raven, B. (2010). Leadership power bases. In J. McMahon (Ed.), Leadership

classics, (pp. 375–389). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Gustafson, K. L., & Branch, R. M. (2002). Survey of instructional development models (4th ed.).

Syracuse, NY: Eric Clearinghouse on Information & Technology. Retrieved from

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED477517

Intentional Futures. (2016). Instructional design in higher education: A report on the role,

workflow, and experience of instructional designers [White paper]. Retrieved from

https://intentionalfutures.com/insights/portfolio/instructional-design/

Ivankova, N. (2015). Mixed methods applications in action research: From methods to

community action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kadi-Hanifi, K., Dagman, O., Peters, J., Snell, E., Tutton, C., & Wright, T. (2014). Engaging

students and staff with educational development through appreciative inquiry.

Innovations in Education & Teaching International, 51(6), 584–594.

doi:10.1080/14703297.2013.796719

Kiersch, C. E., & Byrne, Z. S. (2015). Is being authentic being fair? Multilevel examination of

authentic leadership, justice, and employee outcomes. Journal of Leadership &

Organizational Studies, 22(3), 292–303. doi:10.1177/1548051815570035

Molenda, M. (2003). In search of the elusive ADDIE model. Performance Improvement, 42(5),

34–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.4930420508

The Collaborative Mapping Model: Relationship-Centered Instructional Design for Higher Education

Online Learning Journal – Volume 23 Issue 3 – September 2019 5 71

Neibert, J. (2013-a, October 7). Agile instructional design: The big questions. Learning Solutions

Magazine. Retrieved from https://learningsolutionsmag.com/articles/1262/agile-

instructional-design-the-big-questions

Neibert, J. (2013-b, November 6). Agile instructional design: Get in the performance zone.

Learning Solutions Magazine. Retrieved from

https://learningsolutionsmag.com/articles/1300/agile-instructional-design-get-in-the-

performance-zone

Neibert, J. (2014, February 6). Effective performance with A.G.I.L.E. instructional design.

Learning Solutions Magazine. Retrieved from

https://learningsolutionsmag.com/articles/1346/effective-performance-with-agile-

instructional-design

Saba, F. (2011). Distance education in the United States: Past, present, and future. Educational

Technology, 51(6), 11–18. Retrieved from

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/022b/615817dbd609d08f2f3e60033ea92cd9016d.pdf

Seaman, J., Allen, I., & Seaman, J. (2018). Grade increase: Tracking distance education in the

United States [White paper]. Retrieved from

https://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradeincrease.pdf

Shaw, K. (2012). Leadership through instructional design in higher education. Online Journal of

Distance Learning Administration, 15(3). Retrieved from

http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/fall153/shaw153.html

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA:

Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.