Suicide and its Prevention

among Older Adults

Dr. Marnin J. Heisel, Ph.D., C.Psych.

The University of Western Ontario;

Lawson Health Research Institute

Project ECHO Presentation

Monday, April 17, 2023

Address: Dr. Marnin J. Heisel,

Parkwood Institute Mental Health Care Building,

550 Wellington Rd., Office #F4-365

P.O. Box 5777 STN B.,

London, Ontario, N6A-4V2

Phone: 1-519-685-8500 extension 75981

E-Mail: [email protected]

Web: Meaningfulgroups.com

Contact Information

-American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

-Canadian Institutes of Health Research

-Centre for Aging and Brain Health Innovation, Baycrest

-Employment and Social Development Canada

-Lawson Health Research Institute

-Movember Canada

-Ontario Mental Health Foundation

-Ontario Ministry of Research & Innovation

-Public Health Agency of Canada

-Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

-UWO Department of Psychiatry

Funding Acknowledgements

• Thank you to all of my research assistants,

students, clinical trainees, and colleagues who

have collaborated on this work over the years.

• My sincerest thanks to all of my clients and

research participants and to all of the

community members who have made this

work possible and meaningful.

Acknowledgements

Learning objectives:

By the end of this presentation, you will be able to:

1. Demonstrate an increased understanding of the

epidemiology and risk and resiliency factors

associated with suicide among older adults;

2. Show familiarity with a humanistic approach to

suicide risk assessment and response with older adults;

3. Discuss evidence and opportunities for suicide

prevention among older adults across clinical,

community, and population health levels.

Let’s start with a few quick

multiple-choice questions…

1. Which of the following statements is most true of

suicide in Canada?

a) Men in their 70s and older have suicide rates that more

than double the national average.

b) Older adults have higher suicide rates than adolescents

c) More adolescents die by suicide than older adults.

d) Middle-aged men have the nation’s highest suicide rate.

2. The strongest risk factor for suicide among older

adults is ____________.

a) Depression c) Misuse of alcohol/substances

b) Previous suicidal behaviour d) Social isolation

3. Which of the following factors have been shown to

increase risk for suicide AND for MAID?

a) Pain and suffering

b) Depression

c) Loneliness

d) Feelings of meaninglessness

e) Feeling like a burden on others

f) All of the above

g) None of the above

4. Although few clinical trials exist that specifically

focus on older adults, evidence from controlled

clinical research trials supports which of the following

modes of psychotherapy for reducing suicide ideation

or the likelihood of repeating suicidal behaviour?

a) Psychodynamic psychotherapies

b) Interpersonal psychotherapies

c) Cognitive behavioral psychotherapies

d) Supportive psychotherapies

e) All of the above

f) None of the above

5. Research on depression screening in Japan and

telephone support in Italy suggests that __________.

a) Community outreach interventions may help prevent suicide

among older adults.

b) Community-level interventions may be ineffective at

preventing suicide among older adults.

c) Effective communication is required in order to prevent suicide

among older adults.

d) Medication is required in order to prevent suicide among older

adults.

6. Which of the following statements is false regarding

late-life suicide risk?

a) Suicidal thoughts can come and go and increase and decrease

over time.

b) Risk for suicide may be high when someone starts emerging

from a depressive episode.

c) Asking about suicide will plant the idea in an older person’s

mind.

d) Take any threat of suicide or wish to die seriously.

7. Which of the following is a key message in the field

of suicide prevention?

a) When assessing suicide risk, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

b) Suicide prevention is everybody’s business.

c) Don’t ask, don’t tell.

d) Only you can prevent deaths by suicide!

• For at least the past 3 decades, there has been increasing

focus on suicide as a public health issue, and suicide

prevention efforts employing a public health lens.

• In so doing, many have focused on British

Epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose’s Theorem:

“a large number of people at small risk may

give rise to more cases than a small number of

people at high risk”

Rose (1985)

• That having been said, does it make sense to

exclusively focus on preventing suicide among

people at low risk for suicide?

• Should we not also focus on people at

moderate risk?

• And should clinicians not be exceptionally

concerned about people at high risk?

• According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC), there are 4 steps to a public

health approach to violence prevention:

• Step 1: Define and Monitor the Problem;

• Step 2: Identify Risk and Protective Factors;

• Step 3: Develop and Test Prevention Strategies;

• Step 4: Assure Widespread Adoption

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/publichealthapproach.html

• Every day, roughly 11 people die by suicide in Canada

• Of those people:

• 9-10 would meet criteria for a mental disorder

• 8 are Male

• 4 are in Ontario

• 2 are over the age of 65

• 1-2 use a firearm (and are male, and older)

Suicide in Canada: A Picture of a Typical Day

• In addition, a further 28 people every day die by

MAID (most of whom are over the age of 60, and

roughly half of whom are Female).

• I no longer think we can address the issue of suicide

among older adults in Canada without simultaneously

considering the issue of MAID.

• Although these are defined as distinct entities, and

relevant data are housed in different locations, there is

considerable overlap between the two.

• According to the World Health Organization

(WHO, 2021), suicide accounts for 1% of all

deaths worldwide, or 703,000 lives lost every year.

• Although a low percentage, this number is

extremely high, exceeds the global number of lives

lost to war & homicide combined, and yet reflects

a recent reduction in deaths by suicide.

• In 2014, the WHO reported over 800,000 annual

deaths to suicide worldwide; in earlier years, this

figure exceeded 1,000,000 lives lost to suicide.

• This reduction appears to support the effectiveness

of suicide prevention strategies and programs.

Epidemiologic Background

• Although suicide is a global problem that

affects people of all social classes, religions,

cultures, ethnicities, and nations of origin,

it does so unequally and inequitably:

• Suicide rates vary by country

• Suicide rates vary by geographic region

• Suicide rates vary by social stratum

• Suicide risk varies by profession

• Suicide risk varies by age

• Suicide risk varies by sex (and sexual identity)

• Suicide risk varies by culture and ethnicity

• Suicide risk varies by health condition

• The costs of suicide are staggering.

• A Canadian report on injury estimated that Suicide

and Self-Harm together accounted for 11% of total

costs of injury in Canada in 2010, and exceeded

$2.9 Billion/year (Parachute, 2015).

• However, there is no price that can capture the

deeper emotional impact of this loss of human life.

• The global older adult population is expanding.

• People are living longer; reduced mortality to childhood

illness and infectious disease* and decreased birth rates

contribute to increased longevity (NIA/WHO, 2011).

• The over-65 population could increase from 524MM

in 2010 to nearly 1.5 Billion people by 2050, or 16%

of the world’s population (U.S. NIA/WHO, 2011).

• 20-25% of the North American population (75MM+)

will be over 65 by 2030 (Statistics Canada, U.S. NIA).

• Nearly 1 in 8 older Canadians is 85+ (Statistics Canada).

* It is yet unclear what medium-to-longer-term impacts

COVID will have on population demographics.

Demographics of the Aging Population

Year

25

20

15

10

5

0

1921 1931 1941 1951 1961 1971 1981 1991 2001 2011 2021 2031 2041

Percentage

65-74 75-84 85+

Older Adults (by age sub-groups) as

% of the Total Population

Canada, 1921-2041

Source: The Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health

• Baby-boomers (DOB: 1946-1964) have high rates of

suicide as compared with earlier cohorts.

• More than 9,500 North Americans over 65 die

by suicide annually or more than 18,000 over 55;

this number is growing (CDC, StatsCan).

• Canetto’s “gender paradox of suicide”: women are

far more likely to engage in suicide behaviour, and

yet men are far more likely to die by suicide.

• Older men have the highest rates of suicide globally;

middle-aged men account for the highest number of

deaths by suicide in North America.

• Among North American women, suicide rates are

highest in mid-life.

• Sex and age differences are apparent when reviewing

national and global trends in suicide.

• In North America, men account for 75% of deaths by

suicide, and typically employ highly lethal means.

Sex Differences

• 2020 North American mortality data indicate:

• 45,979 people died by suicide in the U.S.A.,

including 36,551 men or boys (M: 79.5%) and

9,428 women or girls (F: 20.5%), for a national

suicide rate of 13.95/100,000 overall, 22.5/100K

for M, & 5.6/100K for F (U.S. CDC; WISQARS).

• 3,839 people died by “suicide” in Canada,

including 2,874 men or boys (M: 75%) and

965 women or girls (F: 25%) for a national suicide

rate of 10.1/100,000 overall, or 15.2/100K for

M and 5.0/100K for F (Statistics Canada).

Canadian Suicide Rates by Sex and Age for 2020

0

10

20

30

40

M

F

All

Source: Statistics Canada

Note: Overall National suicide rate = 10.1/100K

American Suicide Rates by Sex and Age for 2020

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Chart Title

M

F

All

Source: WISQARS (CDC)

Note: Overall National suicide rate = 13.95/100K

• Suicide rates are often undependable and

underestimate “true” suicide rates, especially if

means of suicide are equivocal (e.g., medication

overdose, Ohberg & Lönnqvist, 1998).

• Ontario has Canada’s most stringent regulations

regarding classification of suicide, making Canada-

wide comparisons difficult.

• Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID), which was

initially legalized in 2016, has complicated things

further.

• Statistics Canada does not report on MAID deaths.

• Although there was a noticeable (10-15%) reduction

in deaths by suicide early into the pandemic, surveys

have noted increased psychological distress, and

health care systems saw increased need.

• Moreover, the number of older adults who died by

suicide in Canada did not decline, consistent with the

fact that the number of older adults who die by

suicide is increasing as the population grows.

• 3,606 individuals died by suicide in Canada in 2000;

by 2020, this figure increased 6.5% to 3,839.

• 402 older adults died by suicide in Canada in 2000;

by 2020, this figure increased by 64% to 658.

Numbers of Deaths by Suicide among Adults 65+ in the U.S. (1999-2020)

Source: WISQARS, U.S. CDC

• Again, these figures do not include deaths by

Medical Assistance in Dying (or MAID).

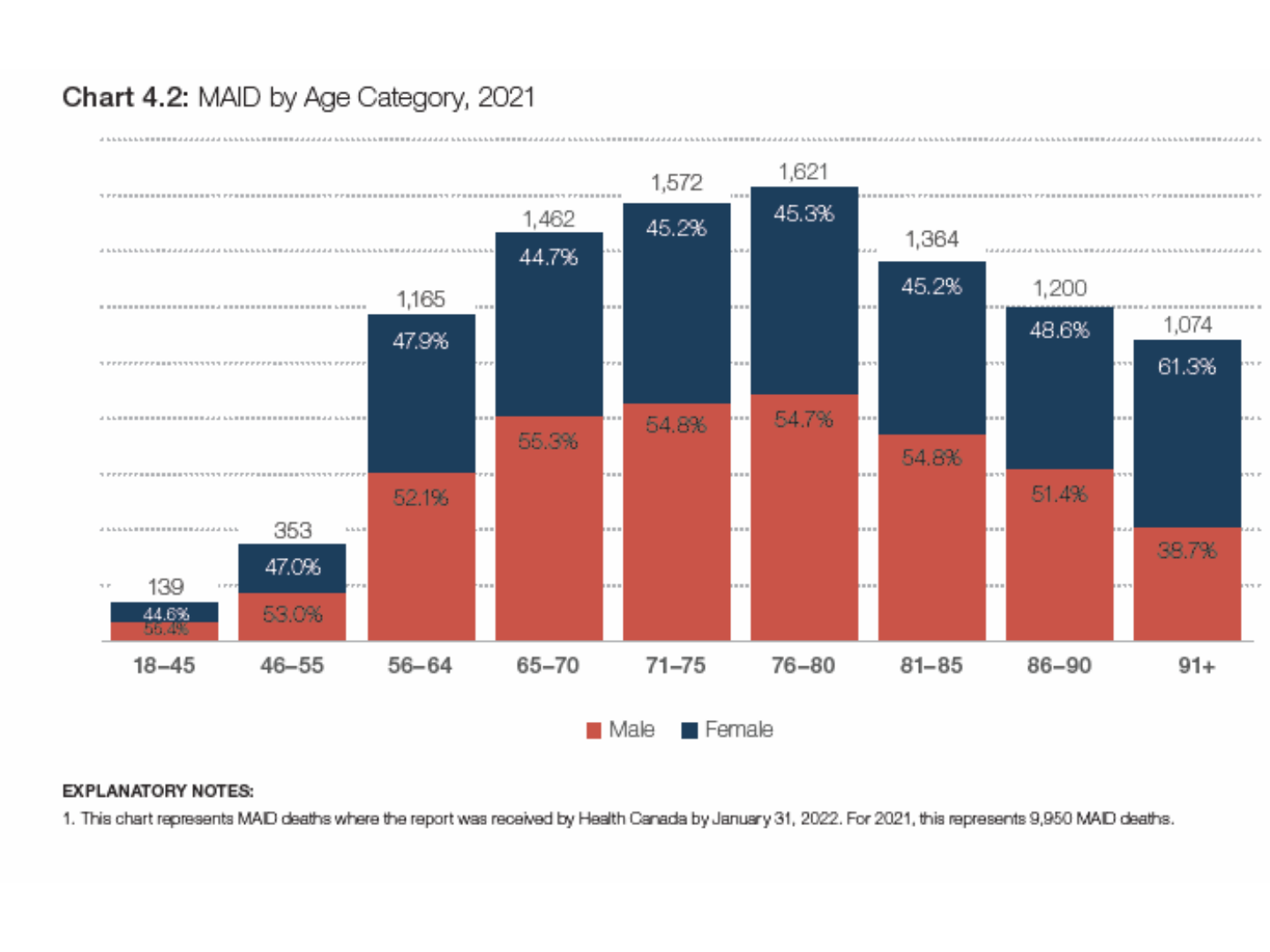

• The average age of Canadians who accessed MAID

in 2021 was 76.3 years.

• 10,064 Canadians died by MAID in 2021, reflecting

a 32.4% increase over 2020 (in addition to a 34%

annual increase over 2019).

• And so we might not have seen increases in suicide,

per se, during the pandemic; but we have certainly

seen a massive increase in self-determined deaths.

• This will only increase in coming years, as the limits

on MAID are further expanded to include those with

a primary mental disorder.

Source: Health Canada, 2022

Source: Health Canada, 2022

“The most commonly cited intolerable physical or

psychological suffering reported by individuals

receiving MAID in 2021 was the loss of ability to

engage in meaningful activities (86.3%), followed

closely by the loss of ability to perform activities of

daily living (83.4%).”

-Health Canada (2022)*

*Third Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada 2021

• Psychological problems are not inevitable with aging

•Most middle-aged and older adults are emotionally

well-adjusted.

• However, roughly 15% of adults over 60 suffer from

a mental disorder (WHO, 2017) which can contribute

to poor life satisfaction, functional decline, and

increased mortality, including by suicide.

• Challenges abound in accessing quality mental

healthcare for older adults.

• Innovative approaches are needed.

Mental Health and Aging

Risk and Protective Factors

Suicide Assessment & Prevention for Older Adults

Clinician Pocket-Card

RISK FACTORS:

1. Suicidal Ideation and/or Behaviour

⚫ Prior suicidal behaviour (including suicide attempt), prior

self-harm behaviour, previous expression of suicide ideation

⚫ Feels tired of living and/or wishes to die

⚫ Thinks about suicide, has suicidal wishes and/or desires

⚫ Has a suicide plan/note

⚫ Access to a firearm or other means of suicide

2. Family History

⚫ Family history of suicide, suicide ideation, mental illness

RISK FACTORS (Cont.):

3. Mental Illness (can include)

⚫ Any mental disorder, co-morbidity

⚫ Major depressive disorder

⚫ Any mood disorder

⚫ Psychotic disorder

⚫ Substance misuse disorder/addictions

4. Personality Factors

⚫ Personality disorders

⚫ Emotional instability

⚫ Rigid personality

⚫ Poor coping skills, introversion

RISK FACTORS (Cont.):

5. Medical Illness

⚫ Pain, chronic illness

⚫ Sensory impairment

⚫ Perceived or anticipated/feared illness or decline

6. Negative Life Events and Transitions

⚫ Family discord, separation, death or other losses

⚫ Financial or legal difficulties

⚫ Employment/retirement difficulties

⚫ Relocation stresses

7. Functional Impairment

⚫ Loss of independence

⚫ Problems with activities of daily living

Suicide Assessment & Prevention for Older Adults

Clinician Pocket-Card

RESILIENCY FACTORS:

1. Religious (or spiritual) practice.

2. Sense of meaning and purpose in life.

3. Sense of hope or optimism.

4. Active social networks and support from family and friends.

5. Good health care practices.

6. Positive help-seeking behaviours.

7. Engagement in activities of personal interest.

⚫ It is not enough to simply take stock of the

various risk and protective or resiliency factors

present in a given individual; we must

conceptualize how these combine to increase,

maintain, or reduce that individual’s risk for

suicide, over immediate, moderate, and long-

term periods.

Our Conceptual Framework

(e.g., Heisel & Flett, 2014)

Risk Assessment

• Suicide risk assessment must be carried out in a

sensitive fashion, in the context of a trusting

therapeutic relationship

• Rating scales and other measures can be helpful, but

are insufficient on their own to assess risk

• Be aware of validity issues; don’t just take

self-reports at “face value”

• Work within your skill-set and competencies; use of

assessment tools requires appropriate training

• There is no such thing as a “best” screening or

assessment tool; rather certain tools are more

appropriate in particular contexts and populations

• Professional geropsychology guidelines recommend

use of age-specific measures developed and/or

validated with older adults (APA, 2004).

• We saw the need for a tool to specifically assess

older adult suicide risk and resiliency, and developed

the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale to meet this need

(GSIS; Heisel & Flett, 2006).

• More recently, we developed an abbreviated, 5-item

GSIS-Screen for use in health screenings, residential

care, and clinical practice (Heisel & Flett, 2022).

CCSMH Suicide Assessment & Prevention for

Older Adults Clinician Pocket-Card

Assessment Process:

1. Establish rapport and assess for suicide risk in a sensitive

and respectful fashion.

2. Respect the dignity of older adults. Acknowledge their

experiences and validate their feelings.

3. Assess for suicide risk factors.

4. Assess for psychological resiliency.

5. Assess for suicide warning signs IS PATH WARM.

Assessment Process (Cont.):

6. Where appropriate, access collateral information

(medical chart, family members, other providers).

7. Be mindful of ambivalent wishes to live and to die.

8. Develop a risk management/action plan.

9. Seek consultation and/or assistance if you do not have

specialized training in mental health or in suicide

prevention.

Suicide Assessment & Prevention for Older

Adults Clinician Pocket-Card

KEY QUESTIONS:

1. Ask about their feelings

⚫ Do you feel tired of living?

⚫ Have you been thinking about suicide?

2. Ask about a suicide plan

⚫ Have you made any specific plans or preparations

(giving away possessions, tying up 'loose ends')?

⚫ Do you have access to lethal means like a gun or other

implements?

3. Ask about their reasons to live

⚫ Who or what makes life so worth living that you would

not harm yourself?

Q: Can suicide be predicted?

• Suicide is a low base-rate phenomenon, and is thus

extremely difficult to predict on an individual basis.

• This yields a problem with specificity.

• Prediction of suicide requires immense sample sizes

and long follow-up periods.

• Most studies do not differentiate imminent from

lifetime elevated risk; but this is what is needed in

healthcare settings.

• The jury is out on the potential effectiveness of

Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning approaches

in potentially predicting deaths by suicide

Suicide can be prevented!

Prevention

Intervention

Postvention

The Language of Prevention Science

(U.S. Institute of Medicine)

• Universal = At the population level

(primary)

• Selected = For a group with elevated risk

(primary)

• Indicated = For those at imminent risk

(secondary early intervention)

• Prevention strategies are needed at all levels!!

• Public health initiatives (Universal)

• Means restriction (medication packaging, CO, bridge

barriers, firearms, media guidelines)

• Clinician education (screening & intervention)

• Suicide prevention strategies/treatment guidelines

• Community initiatives (Selected)

• Gatekeeper training and response/referral

• Community outreach/support (DeLeo et al., Oyama et al.)

• Clinical initiatives (Indicated)

• Psychotherapy (+ medication, and possibly ECT)

• Emergency Cards and caring letters

• Organizational change

Empirically-Supported Initiatives

• Effective public health approaches can include:

• Education (providers, clients, communities, the media)

• Community outreach (screenings) and response

• Means restriction (e.g., guns, alcohol/drugs, “hot spots”)

• Access to and delivery of effective mental healthcare

• Collaboration between primary care, mental health,

social service providers, older adults and their families

• Enhanced/integrated systems of care

• Grassroots efforts

• Screening high-risk demographics and high-risk settings

• Plus, research, dissemination, and training

(see Mann et al., 2005; Zalsman et al., 2016)

Clinical Interventions

• There had been a paucity of RCTs with suicidal

individuals; suicide risk had been a typical exclusion

factor in treatment studies (e.g., Pearson et al., 2001)

• There has been an increase in research on this issue

in recent years; in the U.S., efforts had largely been

spearheaded by military and veterans groups 10-15

years ago, with uptake by other Federal funders

• Efforts are underway in the U.S. and Canada to

develop strategic research priorities for suicide

prevention; these must include focus on older adults

• Health care organizations are increasingly looking at

management approaches

•Lithium

(Angst et al., 1999; Baldessarini et al., 1999; Goodwin, 1999)

•Clozapine (Meltzer et al., 2003)

•Other antipsychotics (Hawton et al, 1998; Palmer et al,1999)

•Antidepressants (Angst et al., 1999)

•ECT (Prudic & Sackeim, 1999)

•These studies were not specific to older adults

MEDICAL INTERVENTIONS

• Cognitive approaches:

• Cognitive Therapy (Brown et al., 2005)

• DBT (Linehan et al., 1991, 2006)

• Problem-Solving Therapy (Salkovskis et al., 1990)

• Interpersonal approaches:

• Brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy

(Guthrie et al., 2001)

• Interpersonal problem-solving (McLeavey et al., 1994)

• Interpersonal Psychotherapy (Alexopoulos et al., 2009;

Heisel et al., 2009, 2015)

• Meaning-centered approaches (Breitbart et al, 2015;

Heisel et al., 2020; Lapierre et al., 2007)

PSYCHOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS

• Human beings are more important than things; respect the

inherent value and dignity of all people and honour their

wishes to take an active role in their lives and communities.

• Everyone is unique. No single approach fits equally well

for all people; avoid “cookie-cutter” programs or strategies.

• Take the time to really listen to each client; learn who they

are, their history, hopes, experiences, who matters to them,

and what makes life meaningful for them.

• Ask “how would I like to be treated in their circumstances?”

• Focus on the “here and now” but be open to wishes to

reflect/reminisce and to think about the future.

• Growth and development does not stop at a particular age;

aging is as much a state of mind as of body or of time.

Some Humanistic Principles in Gerontology

Recommendation: Treatment and Management:

• Develop a trusting and genuine therapeutic relationship with

at-risk older adults. Actively and attentively listen to the

client, and take your time. When present, these elements

help contribute to a person feeling heard and respected, and

can help contribute to the older client feeling connected.

• Foster hope in clients who are suicidal. Health care providers

may promote hope by initiating hope-focused conversations.

• Health care providers should explore strategies to assist older

persons find and maintain meaning and purpose in their lives.

• When older adults access mental healthcare services,

they rarely receive recommended care due in part to a

paucity of provider knowledge and skill in suicide risk

detection and intervention (Heisel & Duberstein, 2005).

• Education and training can effectively enhance provider

knowledge and attitudes towards working with suicidal

individuals (Huh et al., 2012; Schmall & Pratt, 1993).

• Educational interventions are needed in order to

enhance provider knowledge and skill in delivering

competent care to those at-risk.

• We initially evaluated focused training sessions

incorporating a set of knowledge translation tools

developed together with the Canadian Coalition for

Seniors’ Mental Health (CCSMH).

Training Needs

⚫ We evaluated dissemination of the CCSMH tools by

delivering half-day workshops to frontline providers

employing these tools.

⚫ We assessed change in knowledge and attitudes toward

working with older adults at-risk for suicide using two

scales we developed for this purpose.

⚫ Findings indicated significant improvement in provider

knowledge and attitudes reflecting greater comfort and

perceived competence in working with older adults

regarding risk for suicide.

CIHR Betty Havens Award for KT in Aging

Enhanced competency in

assessing suicide risk

and providing care for

at-risk older adults

Professional

Skills and

Experience

Attitudes Towards

Working with

At-Risk Older Adults

Knowledge about

Late-Life Suicide

and its Prevention

Our Model

• We will be expanding on this approach in a CIHR-

funded study on screening for suicide risk among

older residents of Ontario Long-Term Care Homes.

• This project involves:

• Educating on-site personnel to sensitively screen for

(and respond appropriately to) suicide risk;

• Evaluate screens for suicide ideation (SI);

• Identify the prevalence of suicide ideation and

behaviour in LTC;

• Test a theoretical model of SI; &

• Explore similar issues with respect to MAID.

• In order to improve suicide prevention, we need to:

• raise awareness

• improve risk detection

• enhance understanding of risk/resiliency factors

• develop and test innovative interventions

• develop/deliver individualized approaches to care

• improve education and training for professionals

• engage in knowledge translation and dissemination

• revise/adapt/test policy changes

• MAKE IT A NATIONAL PRIORITY!

Research and Clinical/Systemic Needs

• Canada does not yet have a National Strategy for

Suicide Prevention!

• Healthcare in Canada is managed at the level of the

provinces and territories not at a Federal level.

• Nevertheless, Federal efforts are underway regarding

suicide prevention, including:

• a “Federal Framework” for suicide prevention,

• efforts to develop strategic research priorities,

• a national demonstration project,

• focused scoping reviews,

• a proposed 3-digit suicide prevention crisis line.

Do suicide prevention strategies work?

• The global suicide rate decreased by 36% overall

from 2000-2019, ranging from a 17% decline in the

Eastern Mediterranean Region to more than a 47%

decline in Europe and Western Pacific Regions.

• This suggests that suicide prevention strategies,

guidelines, and other initiatives are effective.

• Yet, in the Americas, it INCREASED by 17%.

• More work clearly remains to be done!

• Treating mental health problems is necessary.

• Existing approaches tend to be reactive, focusing on

treatment of symptoms and disorders, rather than

on promoting mental health and well-being among

older adults; “upstream” approaches are also needed.

• More attention is needed to building social

connections and support and in enhancing

psychological resiliency (i.e., the ability to cope

with stress, bounce back, and learn and grow from

adversity) and well-being.

What Can We Do?

• Although there has been a paucity of research explicitly

focusing on the prevention of suicide among older

adults, community efforts have shown promise in

reducing risk (DeLeo et al., 2002; Oyama et al., 2005);

benefits were mainly found for women

(Duberstein, Heisel, & Conwell, 2011).

• “Upstream” preventive interventions are needed

designed to enhance psychological resiliency for

middle-aged and older men (CCSMH, 2006).

• It was with those considerations in mind that my

colleagues and I developed Meaning-Centered Men’s

Groups (MCMG; Heisel et al., 2016, 2018, 2020).

• Group meetings focus on discussions of:

• Meaning in work and career

• Meaning in productivity and societal contribution

• Meaning in mentorship and volunteerism

• Meaning in leisure and recreation

• Meaning in relationships, love, and friendship

• Attitudes towards life’s challenges and transitions

• Attitudes towards positive experiences

• Generativity, spirituality, and end-of-life issues

• We pivoted our groups online during the pandemic.

• We then further adapted them (as Online Meaning-

Centered Groups or OMG) for delivery to Retirement

Home residents and other Ontarians over 60 struggling

with loneliness, isolation, and pandemic-related

psychological distress (CABHI and New Horizons).

• We have received Movember funding to adapt MCMG

for Veterans and First-Responders facing a career

transition and are actively recruiting for this study.

• www.meaningfulgroups.com

What’s Next?

• We cannot predict who will die by suicide; however, we can

and must assess suicide risk (and resiliency)

• Outreach is critical for detecting at-risk individuals;

don’t forget to follow-through

• Make suicide risk assessment part of usual practice, even

when you don’t think it’s present

• Routinely assess access to firearms and other lethal means

• Assess history of suicidal behaviour; one of the strongest

risk factors for death by suicide

• Be open to discussions of suicide-it takes time and should

• Consider use of rating scales

• Work in teams wherever possible

• Communication among providers is absolutely critical

Treatment Implications

• This is a free webinar series, taking place on roughly a

monthly basis, focusing on suicide and its prevention.

Everyone is welcome.

• Feel free to e-mail me to ask for your e-mail to be added to

our distribution list: [email protected]

• Recent decades have witnessed an increased

public health focus in the field of suicide prevention.

• This has helped the field move away from

exclusively clinical approaches, promoted evaluation

of intervention programs, and communicated the

message that suicide is not solely a clinical, medical,

or biological entity, but one with clear psychological

and social contributors and implications.

• However, we need to ensure that we do not go too

far in the other direction.

• Innovative, multi-level, multi-perspective, and truly

interdisciplinary approaches are needed.

Summary

• Moreover, we must take into consideration the lived

experience of older adults, their family members

and other supports, and healthcare providers if we

wish to truly impact the health and well-being of

older adults and not only prevent suicide but

enhance life.

Thank You